Qihep

| Ul la Qīxēp ā xūc vol dī tȳn la dōb topīk |

| Welcome, students of Qihep! |

Qihep (in Qihep: Qīxēp [ˌkʷiːˈxeːp]) is a constructed fantasy language. It is an isolating language and uses a logographic script.

Phonology

There are 23 consonants (with 2 allophones and 1 unrecognized phoneme) and 6 vowels (with long and short variants)

Consonants

| Consonants | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Labialized velar |

Glottal | ||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | g | kʷ | (ʔ)1 | ||||||||||||

| Nasal | m | (ɱ)2 | n | ɲ | (ŋ)3 | |||||||||||||||

| Vibrant | r | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | ʃ | x | h | ||||||||||||||

| Affricate | ʦ | ʧ | ʤ | |||||||||||||||||

| Approximants | j | w | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximants |

l | |||||||||||||||||||

Note:

- [ʔ]1is not recognised as an independent phoneme but it is inserted between two vowels, or between two identical consonants.

- [ɱ]2 and [ŋ]3 are considered as allophones of the normal nasal phonemes in front of [f]/[v] and [k]/[g]/[kʷ] respectively.

Vowels

| Vowels | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Near- front |

Central | Near- back |

Back | ||||||||||

| Close | i(ː) | u(ː) | ||||||||||||

| Close mid | e(ː) | o(ː) | ||||||||||||

| Mid | ə(ː) | |||||||||||||

| Open | a(ː) | |||||||||||||

Every vowel can be distinctively short and long.

If two vowels are adiacent in a compound word, a glottal stop ([ʔ]) emerges to keep them separated.

Syllabic structure

Maximal syllabic structure is CCV(ː)C, while the minimal is the simple vocalic nucleus V.

For the consonantic coda CCV(ː)C, every available consonant is allowed, except for [ʦ], which counts as two consonants and has too much syllabic weight.

For the consonantic onset CCV(ː)C, these are the constrains:

When the onset has a single consonant CV(ː)C, every available consonant is allowed.

When the onset has two consonants CCV(ː)C, there are some restrictions:

- No double consonants or long consonant is allowed.

- The consonant [ʦ] counts as two consonants and takes the entire onset of the syllable, allowing no consonant before or after itself.

- The consonants [ʧ], [ʤ] and [kʷ] count as one consonant, allowing other consonants before themselves.

- If the second consonant is a liquid, Cl or Cr, the first consonant can be only [b], [p], [k], [g], [t], [d], [f], [v], [h], [x], [s] or [ʃ]

- If the first consonant is s or ʃ, every available consonant is allowed as the second consonant except for the two consonants themselves, [s] and [ʃ]. and [ʤ].

The restrictions for the syllabic onset do not apply between syllables. The only rule which is always applied is the no double consonants rule: when two identical consonants find themselves together between syllables, a glottal stop [ʔ] emerges and keeps them clearly separated.

Stress and tones

Every monosyllabic word has its own stress, which does not affect the lenght of the vowel. Since every syllable can have only one vowel as its nucleus, stress marks no difference between any monosyllabic words.

Stress plays a bigger role when words are combined in a compound. In such words the stress of the final syllable is perceived as the main stress (primary) of the new compounded word. The previous accent turns itself in a secondary stress.

- [ˈmar] + [ˈmeʃ] → [ˌmarˈmeʃ]

When a compound is formed with three or more monosyllabic word, only two stress, the primary one on the last syllable and the secondary one, are usually kept. Which of the previous syllable is to be kept stressed is not easily predictable. One predictable case is when the word is formed with an already existing compound word, when the former primary stress turns in the new secondary one:

- [ˈfa] + [ˈskət] → [ˌfaˈskət] ˃ [ˌfaˈskət] + [ˈvran] → [faˌskətˈvran]

These rules are routinely applied with foreign names too, but some of them can retain their orriginal stress position.

Tones

Long vowels show a tonal feature, which is however not distinctive at all in monosyllabic words. In such words the vowel are pronounced with a rising tone:

- [xěːp] or [xeːp˧˥] or [xeːp35]

As already say tone is not distinctive between words (like Chinese) and its only a feature of the vocalic nucleus of the syllable. However, tone plays a bigger role, again, when words are combined in a compound. In such words a phenomenon of tonal samdhi appears. The tone of the last long vowel preserves its original rising value, while the previous long vowels are pronounced with a mid tonal value:

- [kʷ◌̌iː] + [xěːp] → [kʷīːxěːp] or [kʷiː˧˥] + [xeːp˧˥] → [kʷiː˧xeːp˧˥] or [xeːp35] + [xeːp35] → [kʷiː33xeːp35]

Script

Qihep is written with a partially logographic script. It means that every syllable is written with a character, which is a little drawing, often somehow related to the meaning of the word it represents. The script is partially logographic, since many characters have lost their apparent relation to the meaning and are simple drawings. Every character gives no information about the phonetic nature of the syllable it represents.

Words are not written separately nor sentences are. Only sentences can be separated by the space of a character, when there is a pause in the speech or when the two sentences are clearly distinct in meaning.

The space between the characters is usually the same, compounds syllables are not written closer than the other ones, even if the word is perceived as a compound.

Characters can be used for their phonetic value, usually to express foreign names or proper names which have no logographic representation. In this case they are marked by underline.

Underlined characters are thus read for their sound, with no attention for the meaning of the syllable.

Direct speech is written between two soundless characters, that are comparable to our inverted commas.

Transcription

Qihep can be easily transcribed using the Latin script. Trascription is based on the phonemes of the languages with no regard for the nature of the characters used in the logographic script.

This is the trascription used:

| Letter | a | ā | b | c | d | e | ē | f | g | ǵ | h | i | ī | j | k | l | m | n | ń | o | ō | p | q | r | s | ś | t | ts | u | ū | v | w | x | y | ȳ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA value | [a] | [aː] | [b] | [ʧ] | [d] | [e] | [eː] | [f] | [g] | [ʤ] | [h] | [i] | [iː] | [j] | [k] | [l] | [m] | [n] | [ɲ] | [o] | [oː] | [p] | [kʷ] | [r] | [s] | [ʃ] | [t] | [ʦ] | [u] | [uː] | [v] | [w] | [x] | [ə] | [əː] |

The macron ¯ above letters marks long vowels. The letter q represents the labialized velar stop [kʷ], which is perceived as a single phoneme and thus transcribed. The affricate phoneme [ʦ] is perceived as a single sound, but as it counts as two regarding the syllabic structure, it is transcribed with two letters ts to remember its phomenic weight.

Differently from the rules of the logographic script, in the transcription words are separated according to their meaning. Compound words are thus written together to facilitate comprehension. Capitalization is optional, since it has no meaning in a logographic script. Transcribed words are usually capitalized at the beginning of a new paragraph or when expressing a proper name to facilitate comprehension.

The transcription preserves the Qihep use of underline, when a word is written with logograms, which are used for their sound and not for their meaning:

- Ul Rōma fut bim fa vol, I am going to go to Rome

Examples in this grammar are usually given only in transcribed form.

Morphology

Typologically speaking, Qihep is an isolating language, that means its words never change nor add any additional ending to show number, gender, tense, aspect, etc.

Example:

We followed that person: Ul la nār vran ta śak fa

Analysing the sentence: * Ul: means I * la: it's a grammatical particle which shows the idea of plural * nār: means that * vran: means person * ta: it's a grammatical particle, conveying the idea of past * śak: means follow * fa: it's a grammatical particle, conveying the idea of action complete

Grammar roles and complements are conveyed by the position in the sentence, by grammatical particles and by postpositions. Grammatical particles are not strictly needed and can be left out of the sentence if the meaning is clear from the context. For example, in the previous sentence, the particle ta can be easily omitted if it's clear that we are talking about the past.

Even if there is no strict morphology, Qihep words can be compounded to form new words and a complex derivational morphology does exist. For example:

- xep, mouth + svūk, sound → xepsvūk, voice

- troj, to build + -kȳt, noun for the result of the action → trojkȳt, building

Nouns

Nouns do not change for number or for gender.

Nouns denoting humans or animals can be linked to a definite gender by prefixing the terms tan, male or res, female:

- vran, human, person → tanvran, man, resvran, woman.

By reduplicating the nouns we can express the meaning of a collective noun:

- vran, human, person → vranvran, people, population

The particle la can be postponed after the nouns to express plurality, but it conveys also the idea of "many".

- vran(vran) la, many people

Adjectives

Nouns never flect in agreement with the noun they modify and do not change for number or for gender. They are always placed before the noun they modify.

They can be modified by the adverb ply, very.

By reduplicating the adjective we can express an intensive meaning, or roughly the meaning of really.

Comparative and superlative

Comparative forms are expressed in two ways:

1 - by using the reduplicated adjective and marking the second compared object with the postposition fe, with regard to, in relation to

- Ul la fe jūnjūn, I am younger than you

2 - by using the reduplicated adverb ply, very, placed before the adjective. The second compared object is marked with the postposition fe, with regard to, in relation to.

- Rȳs tȳn fe plyply fī, She is taller than him

There is no real distinction between the two ways, and both can be used with no difference in meaning. Compound adjectives and derived adjectives tend to use the second form, while simple and basic adjectives tend to use the first form.

Superlative forms are expressed in the same ways as the comparative forms, with the second compared object is usually ńikmē, ńikvran, everyone, ńikqem, everything, or ńik + any noun.

- Tȳn ńik ul la fe plyply fī, He is the tallest among us

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

Pronouns show a limited gender distinction and mandatorily use the grammar particle la for plural if they refer to plural forms.

| Person | English | Form | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | I | ul | |

| 2nd | you | ma | |

| 3rd | he | tȳn | for humans or animals, male or without defining gender |

| 3rd | she | rȳs | for humans or animals, strictly for female |

| 3rd | it | qem | for objects or small animals |

| 3rd | it | do | indicates something undefined, object or idea, which it has already been talked about, aforementioned |

| recip. | each other | sī | indicates that the subjects perform an action on another object and this viceversa on the subject |

| refl. | self | śy | indicates that the subject performs the action on himself |

When referring to more people or objects, particle la is mandatorily postponed after the pronouns, except for the reciprocal and reflexive forms, which have no plural:

- ul, I → ul la, we

Pronouns do not change for case, as they do in English, but they express their role by using the position in the sentence:

- ul tȳn nat piǵ kra, I can't see him

- tȳn ul nat piǵ kra, He can't see me

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns and adjectives do not exist as independent forms. To express their meaning the normal personal pronouns followed by the genitive particle are used:

- ul, I + dī, of = ul dī, my, mine

Example:

- Ul dī suk pūcin, My hair is black

Interrogative pronouns

There are two basic interrogative adjectives and pronouns

| Form | English | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| wē | who, which | for humans and animals |

| wū | what, which, where | for objects and small animals, it can also express location with locative verbs |

| wō | how much, how many | for quantity, of objects and people, also for time expressions |

- Ma wē ta piǵ fa lo, Who did you see?

- Tȳn la wū skyt sty lo, What are they doing?

- Rȳs wū stā sty lo, Where is she?

Other interrogative pronouns are formed by adding specific nouns:

| wū + meś, place | = wūmeś | where, in which place |

| wū + tsēd, time | = wūtsēd | when, in which period |

| wū + dān, moment | = wūdān | when, in which moment |

| wū + cin, way | = wūcin | how, in which way |

| wū + prīc, reason | = wūprīc | why, for which reason |

| wū + tsel, purpose | = wūtsel | why, for which purpose |

Demonstrative adjectives and pronouns

There are three demonstrative adjectives and pronouns

| Form | English | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| tyk | this | for something or somebody near both the listener and the speaker |

| qē | that | for something or somebody near the listener but far from the speaker |

| nār | that | for something or somebody far from both the listener and the speaker |

Indefinite adjectives and pronouns

Indefinite pronouns are built from indefinite adjectives, almost as in English:

| Indefinite adjectives |

+ vran (human) |

+ mē (one) |

+ qem (theyINANIM.) |

+ meś (place) |

+ ńō (time) |

| ńik (every) |

ńikvran (everybody) |

ńikmē (everyone) |

ńikqem (everything) |

ńikmeś (everywhere) |

ńikńō (everytime) |

| ńak (some, any) |

ńakvran (somebody, anybody) |

ńakmē (someone, anyone) |

ńakqem (something, anything) |

ńakmeś (somewhere, anywhere) |

ńakńō (sometimes, at any time) |

| nan (no, any) |

nanvran (nobody, anybody) |

nanmē (no one, anyone) |

nanqem (nothing, anything) |

nanmeś (nowhere, anywhere) |

nanńō (never, at any time) |

Postpositions

Postposition show the role of the word in the sentences. They are always placed after the noun they modify.

| Form | Name | English equivalent |

Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| wa | Nominative -Subject |

it marks the subject of the sentence | |

| ā | Accusative -Object |

it marks the direct object of the sentence | |

| ū | Dative -Indirect object |

to | it marks the indirect object of the sentence |

| dī | Genitive -Possession |

of | it marks the possessor of something or an attributive relationship |

| ō | Instrument | with, by | it marks the instrument or means by or with which the subject achieves or performs the action |

| e | Comitative | with | it marks the person in whose company the action is carried out |

| se | Abessive | without | it marks the lack or absence of the marked noun |

| ab | Theme | about | it marks the theme, the matter we're talking about |

| bā | Essive-formal | like, as | it marks transmits of making a condition as a quality or a similarity |

| vor | Final | for | |

| par | Causal | because of | |

| fe | Relative | comparing to, in relation with |

|

| ki | ' | against | |

| in | Agentive -Causative |

Used for causative construction | |

| yr | Proximal | near, by | |

| yl | ' | by, at | |

| an | ' | on | With contact |

| xub | ' | over | Without contact |

| pod | ' | under | |

| un | ' | inside | |

| vy | ' | out, outside | |

| ud | ' | from | |

| tsu | ' | from, of | Origin |

| lī | ' | between, among | |

| dū | ' | until | Only for movement in space |

| ras | ' | (many possible) | Movement towards multiple directions |

| o | ' | in, at, by | Related to time |

| on | ' | for | Related to time |

| u | ' | since | |

| bī | ' | until | Only for movement in time |

| ho | Vocative | it marks an element of the sentence which is called |

The first three postpositions (wa, ā, ū) are not mandatory, since they are used only in case of ambiguity. Every other preposition are mandatorily used, except for time preposition with some time construction.

Numbers

Numbers are treated like adjectives and are always placed before nouns.

| Number | Form |

|---|---|

| 1 | mē |

| 2 | xup |

| 3 | ci |

| 4 | vo |

| 5 | qo |

| 6 | bum |

| 7 | śo |

| 8 | rō |

| 9 | va |

| 10 | ty |

| 100 | sto |

| 1000 | qur |

| 1000000 | mil |

| 1000000000 | milar |

To build the higher numbers place the units before the tens, the hundreds, the thousands, etc:

| Number | Form |

|---|---|

| 20 | mēty |

| 30 | xupty |

| 40 | city |

| 200 | mēsto |

| 300 | xupsto |

| 2000 | mēqur |

| 30000 | xuptyqur |

| etc. |

Compound numbers are built by placing the lesser number after the higher one:

| Number | Form |

|---|---|

| 11 | ty mē |

| 15 | ty qo |

| 23 | xupty ci |

| 145 | sto voty qo |

| 2156 | xupqur sto qoty bum |

| 1 259 978 | mil xupsto qoty vaqur qosto śoty rō |

| etc. |

Verbs

Verbs do not change according to time, aspect, mode, number, gender, etc. They are usually associated with grammar particles which convey the negation, the time, the aspect, the modality or the evidentiality of the action. No one of this particle are strictly mandatory if the context is clear enough to express these meanings.

The particles are strictly placed in this order:

| Negation | - | Time | - | Verb form | - | Aspect | - | Mode | - | Evidentiality |

Example:

- It seems they aren't looking for him right now: tȳn la tȳn nat mo qum sty vol nah

Negative particles

- nat: assertive negation, it negate an assertion, a question, a normal sentence

- Ul ma piǵ kra, I can see you → Ul la nat piǵ kra, I cannot see you

- pē: prohibitive negation, it negate an order, expressing a prohibition

- Ma tȳn ma snā dī do kāǵ si fa, Tell him what you know → Ma tȳn ma snā dī do pē kāǵ fa, Don't tell him what you know

Time particles

- ta: past, it locates the action in the past

- rā: remote past, it locates the action in the remote past, historical past or a past that we feel remote and far

- mo: present, it locates the action in the present, it is usually omitted, and when expressed it conveys the meaning of precise present "right now"

- fut: future, it locates the action in the future

- fu ta: future in the past, it locates the action in the (hypotetic) future of a past action (still in the past)

Time particles are often left out, expecially in direct speech, since the time of the action is usually inferred by the context. They are usually used in the first sentences of the speech to temporally localize the action or when omission may cause ambiguity.

Aspectual particles

- fa: perfective, it marks a completed action, with no regard for its effects or results

- ǵa: perfect, it marks a completed action which results are still affecting the moment we are talking about, (= English perfect tenses)

- sty: continous, it marks an uncompleted ongoing action in the moment we are talking about (= English continuous tenses)

- rē: repetitive, it marks an action which is repeated many times (= doing again, keep on doing again)

- sōl: habitual, it marks an action which is routinely or habitually performed (usually, used to)

- pyr: prospective, it marks an action which is about to start in the moment we are talking about (= to be about to)

- maj: experiencial, it marks the fact we have have or never have had experience of the action in the moment we are talking about (ever, never)

Modal particles

- vol: volitive, it conveys intention or will, going to, want

- des: octative, it conveys wish, want, wish, desire

- pos: potentive, it conveys ability, capability, can, know how

- kra: abilitial, it conveys a momentaneus ability, can

- ro: potential, it conveys possibility, may, might

- da: permissive, it conveys allowance, permission, may, allow to

- nec: necessity, it conveys an idea of necessity, must, it is necessary that, it is needed that

- ōb: jussive, it conveys an idea of obligation and duty, have to, to be forced to

- vā: causative, it marks that the action is caused by someone on someone/thing else, let, make, get, have

- kōm: incohative, it marks a beginning action, to begin, to start

- fōr: hypothetical, it marks the uncertainty of the action or that the action is/was/will be hypothetical, maybe, if

- si: imperative, to give orders (usually not used with the negative prohibitive particle).

Modal particles can be used in the same sentences together, since they conveys meanings which can be expressed in the same sentences. If there are two or more modal particles, they follow the order of the list above.

Evidential particles

- nah: reported action, the speaker does not personally see the action, the action is reported by someone else

- box: doubtful action, the speaker does not personally see the action, the action is reported by someone else, but the speaker expresses his/her doubt about its truthfulness

- kap: deduced action, the speaker does not personally see the action, but he/she deduces the action by seeing traces or evidences

Derivative morphology

As usual for an isolating language, words in Qihep can often be used as nouns, adjectives or verbs.

Example:

- Tȳn rȳs ta smāx fa, he kissed her

- Rȳs tȳn dī smāx nat vyūmbēl maj, she has never forgot his kiss

In the first sentence smāx, as in English, plays the role of verb, while in the second sentence it is a noun.

Other example:

- Ul ma mīl, I love you

- Rȳs ma dī mīl wīś sty, she wants your love

- Tyk mīl pej, this is a love song

In the first sentence mīl, as in English, plays the role of verb, while in the second sentence it is a noun and in the third one it is an adjective.

However some derivative suffixes can be added to the words to indicate a more precise meaning:

Verb → Verb

- -vor: it forms a special verbal form, called the supine, which indicates an aim for the same action of the verb (almost corresponding to English construction to [verb])

Verb → Noun

- -kȳt: it forms a noun indicating the concrete result of the action (almost corresponding to English -tion)

- -tān: it forms a noun indicating the ongoing process of the action (almost corresponding to English -ing)

- -mor: it forms a noun for the person who performs the action (corresponding to English -er)

- -oh: it forms a noun for the instrument which the action is typically performed with

- lā. to write → lāoh, pen

- -meś: it forms a noun for the place which the action is typically performed in

- qoc. to cook → qocmeś, kitchen

Verb → Adjective

- -sy: it forms an adjective with a perfective passive meaning (almost corresponding to English -ed). Because of its passive meaning, it cannot be added to intransitive verbs.

- ul la dī mīlsy tanvran, my beloved man

- -or: it forms an adjective with a potential passive meaning that can be [verb]-ed (almost corresponding to English -able, -ible). Because of its passive meaning, it cannot be added to intransitive verbs.

- cax → caxor, to eat → edible

Noun/Adjective → Verb

- -skyt (to make): it forms a verb indicating that the object is made according to the meaning of the adjective or of the noun (almost corresponding to English -fy, to make)

- mē, one + -skyt → mēskyt, to unite

- -bly (to become): it forms a verb indicating that the subject is becoming according to the meaning of the adjective or of the noun (almost corresponding to English to become, to get)

Noun → Adjective

- -im: it forms an adjective with the meaning of full of (almost corresponding to English -ful, -ous, -y)

- vȳl, cloud→ vȳlim, cloudy

- -sē: it forms an adjective with the meaning of deprived of, without (almost corresponding to English -less)

- vȳl, cloud→ vȳlsē, cloudless

Other constructions

- Name of a place + -vran: indicates the common noun for the inhabitants of a place

- Itālia, Italy → Itāliavran, Italian person, an Italian

- Name of a place + -xēp: indicates the common noun for the language related to a place

- Itālia, Italy → Itāliaxēp, Italian language

- Name of something + snakȳt: indicates the science which studies the object

- men, heart → mensnakȳt, cardiology

- Name of something + snakȳtvran: indicates the common name for the person which studies the object

- men, heart → mensnakȳtvran, cardiologist

Syntax

Typologically speaking, Qihep is a strictly SOV language. That means that in the sentences the word order is unvariably Subject-Object-Verb.

- Subject - Object - Verb: Tȳn ma śak sty, He is following you

Word order is usually strictly respected, since words cannot show morphologically their role in the sentence (almost like in English).

Indirect object are usually placed before the direct object.

- Ul tȳn woroh nat kreś maj, I have never given him the key

Other members of the sentences are placed after the object, and they are mandatorily marked by postpositions, except from some adverbs clearly showing their meaning.

- Tȳn trojkȳtxep woroh ō ta āś fa, He opened the door with the key

- Ul tȳn woroh arbultsēd kreś fa, Yesterday I gave him the key

The order of the other elements of the sentence is not as strict as the main elements, but it usually follow the order Place-Manner-Time.

The word order of a Qihep sentence is thus this:

Qihep is thus a consistently head-final language, which implies also other features:

- Adjective-Noun: adjectives are always placed before their nouns

- Genitive-Noun: genitive constructions are always placed before their nouns

- Noun-Postposition: there are only postpositions and no prepositions

- Relative-Noun: relative sentences are always placed before the noun they specify

Let's see an example of a sentence:

Wē ū le ma ul dī woroh arbultsēd kreś fa lo who[IND.OBJ]-[TOP] you I[GEN]-key yesterday give[PER] [QUES] Did you give my key yesterday to whom?

Use of personal pronouns

The use of personal pronoun is not different from English, except that the form of each personal pronoun is always the same. Personal pronouns are always and mandatorily pluralized with the particle la when referring to more than one referents, differently from every other element of the sentence, for which pluralization is always optional.

Thus, differently from English, Qihep has ma for singolar you and ma la for plural you, like many other world languages.

The forms for the third personal pronouns are only apparently similar to English, and there are two pronouns meaning it:

Tȳn can indicate a male referent or a referent whose gender is not known. Only the context can specify which is the chosen gender. It is used also for animals, male or with undefined gender, but not plants. In the plural usually indicates a genderless group, less frequently an all-male group.

Rȳs can indicate only a female referent. It is used also for animals, when their gender is clearly female. In the plural can indicate only an all-female group.

Qem indicates an unanimated real item, or a group of them in the plural. It can be also used for small animals, but this is not very frequent.

Do indicates something undefined, an idea, a spoken subject, not a tangible item. It's rarely pluralized and its meaning is usually something already said or aforementioned

The reciprocal and reflexive personal pronouns are quite peculiar, and they are never pluralized with la:

Sī, the reciprocal pronoun, indicates that the expressed subjects perform the action reciprocally, an idea that it is expressed in English with the form each other. This pronoun never appear as the subject elements but it is usually placed in the direct or indirect object place, or as another element with a postposition. The subject is always in the plural form, since there should be two or more subjects for the action to be reciprocal.

- Ul la sī mīl, They love each other

Śe, the reflexive pronoun, indicated that the expressed subject performs the action on himself, an idea that it is expressed in English with the suffix -self/selves. This pronoun never appear as the subject elements but it is usually placed in the direct or indirect object place, or as another element with a postposition.

- Tȳn śy ēt sty, He is washing himself

Genitive construction

Genitive constructions can specify any element of the sentence (except the verb cluster) and they are mandatorily placed before the element they specify.

When they convey a quality of the modified element, they are usually directly placed before their noun without any particle, as in English.

- Dīn vranvran, the population of the world, world population

When they convey a possession, they are usually marked with the genitive particle dī:

- Xūcmor dī kōr, the book of the student, the student's book

- Ul dī rof, My dog, The dog of mine

The genitive particle can be used to convey qualitative specification, in case of ambiguity:

- Nār vran dī byl, the city of that man, that man's city (the city does not belong to the man, but the simple juxtaposition would be ambiguous in a sentence; moreover the difference between attribute and possession is really difficult to distinguish in such sentences, as in English)

Topicalization

As usual for an isolating language, word order in Qihep is strictly respected. There is, however, a way to alter word order, expecially when it doesn't agree with the topic-comment order.

When the topic is not the subject but another element of the sentence, it can be moved in another position, usually at the first position of the sentence (but also the end of the sentece can be a possible position), or syntactically speaking, it can be topicalized. In this case the topicalizing particle le is mandatorily placed after the new topic element.

- Tȳn wū skyt sty lo, What is he doing? → wū le tȳn skyt sty lo, Is he doing what?

Since the topicalization process can obscure the grammatical role of the element, the element itself is usually marked by the corresponding postposition, even if it is the subject, the direct object or the indirect object. The postposition are left out only if ambiguity is not possible.

- Wē ā le ma ta piǵ fa lo, You saw who?, Who is the one who you saw?

- Wē ū le ma woroh ta kreś fa lo, You gave the key to whom?, Who is the one, who you gave the key?

The subject is usually already the topic of the information and would not need topicalizing. It can however be topicalized, with a meaning of intensification of the topic information.

- Wē le sluh krāx ǵa lo, Who is the one who has broken the vase?

The verbal cluster

The verbal cluster is placed at the end of the sentence. Its core is the verb itself, which conveys only the meaning of the action or the state and its intrinsic qualities, like transitivity, intransivity, etc.

The verbal cluster is usually considered as composed of these elements:

| Negation | - | Time | - | Verb | - | Aspect | - | Mode | - | Evidentiality |

The categories negation, time, aspect, mode, and evidentiality are expressed by grammatical particles. None of these particles is absolutely necessary, and none of this is mandatorily present, except for the verb itself.

Negation is usually considered part of the verbal cluster but it will be analysed separately, because of its different behaviour in the sentence.

Use of temporal particles

Temporal particles express the time at which the action of the verb takes place. Three periods are considered, present, past and future. The perception of what exactly is present, past, or future is very subjective but it depends on how broad is considered "present".

For example, the entire period of time taken in consideration can be considered as present if the action covers the entire period of time and still ongoing.

Ul tyk rok o jy mar sty: I'm working hard this year

English usually shares the same perception of present time.

The absence of time particles, quite common, indicates that the time is the present or that the action or the state is always true or that the information about time is not considered as relevant by the speaker. Only the context can disambiguate which idea the speaker wants to transmit.

Temporal particles are placed just before the verb and after the negation particles.

Ta locates the action in the past, every moment before the present.

- Tȳn la dōm ta bim fa, they went home

- Tȳn la dōm ta bim sty, they were going home

- Tȳn la dōm ta bim ǵa, he has already gone home

Rā locates the action in the remote past, that is a past that we feel remote and far from us; it is therefore very used in history reports, tales, fairytales, and almost for every event that took place before the speaker's birth. Its use may vary from speaker to speaker, as it can be very subjective, when referring to non historical events.

- Tȳn la dōm rā bim fa, they went home (speaking about history, or in a tale)

Mo locates the action in the present; it is usually omitted, but when it is expressed, it conveys the meaning of a precise present moment, like the English adverb "right now" (which is usually translated with).

- Tȳn la dōm mo bim sty, they are going home right now

Fut locates the action in the future, every moment after the present.

- Tȳn la dōm fut bim fa, they will go home

- Tȳn la dōm fut bim sty, they will be going home

Fu ta locates the action in the future in the past, which is a moment located in the future of a past time, but still in the past for the speaker.

- Tȳn ta kāǵ fa tȳn la dōm fu ta bim fa ā, he said they would went home

Time particles are routinely omitted because their information is often considered unimportant or irrelevant. Expecially in direct speech, when the time can be easily inferred by the real context, they are less used than in the written form. They are usually never used when another time indication, like yesterday or tomorrow, is already expressed in the sentence.

In a long text, with many sentences, the time particle is usually placed in the first main sentence and then omitted in the following one, only to be placed again if the time changes. If ambiguity arises, the time particle is added again, expecially if the text is very long and the time need to be reasserted to keep the correct time location.

Use of aspectual particles

Aspectual particles express the verbal aspect, that is how the action or the state extends over time, how it is performed over the time, for example if the action is completed or still ongoing, if it is a habitual action or it is repeated over time. Aspect is not directly related to time and differently from English and other European language, it is expressed in the past, in the present and in the future.

The absence of time particles, quite uncommon, indicates that the aspect of the verb is not considered as relevant for the information by the speaker, for example if the action is simply cited for itself, with no relevance for its real happening.

Fa conveys the idea of a completed action, with no regard for its effects or results; the speaker wants to trasmit the idea that the action or the state is completed and without any mention to possible effects on the time he is talking about. This is called perfective aspect:

- Ul ryb ta cax fa, I ate the fish: the speaker says he ate chicken, with no attention of its effects on the present.

- Ul ryb fut cax fa, I will eat the chicken, the speaker says he will eat chicken and that he will eat it completely.

Ǵa conveys the idea of an action which results still have effects on the moment the speaker is talking about, with the action usually meant as completed; the action is perceived to be just performed. It almost corresponds to the English perfect tenses, and it is called the perfect aspect.

- Ul ta cax ǵa, I have eaten, I have just eaten: the speaker says he ate something, but there something about the action which still affects the present, for example to stress the fact that is stil sated.

Differently from English, which expresses this action with a present perfect tense, Qihep temporally locates the action in the past, as the effects on the present are already expressed by the aspectual particle.

Sty conveys the idea of a ongoing action, marking an uncompleted ongoing action in the moment the speaker is talking about. It almost corresponds to the English continous tenses, and it is called the continuous aspect.

- Ul ryb cax sty, I am eating a fish: the speaker says he's performing the action of eating (usually not marked in the present)

- Ul ryb ta cax sty, I was eating a fish: the speaker says he was performing the action of eating in the moment he is talking about.

Differently from English wich uses perfect continuous forms to express this kind of actions, Qihep marks ongoing action with indication of the moment of their start with the simple continuous forms, not using the perfect forms.

- Ul ryb rok on nat cax sty, I have not been eating fish for a year: the speaker says he have not been performing the action for this time frame. Time is unmarked, that is present, and the aspect is only continous.

Sōl conveys the idea of a habitual action , it marks an action which is routinely or habitually performed. It is translated with the English form usually or the construction used to in the past, and it is called the habitual aspect.

- Ul ryb cax sōl, I usually eat fish, the speaker he has the habit of eating fish

- Ul ryb ta cax sōl, I used to eat fish, the speaker he had the habit of eating fish (and presumably he has not anymore)

Rē conveys the idea of a repetitive action, which is repeatedly performed but not habitually nor regularly. It is translated with the English form again or the construction keep to, and it is called the repetitive aspect

- Tȳn cax rē, He keeps on eating fish, He's eating again and again, the speaker says that the subject is repeatedly performing the action

Pyr conveys the idea of an action which is about to be performed in the moment the speaker is talking about. It is translated with the English about to, and it is called the prospective aspect

- Ul cax pyr, I am about to eating, the speaker says that the action of eating is not yet begun but it is about to do so.

Maj conveys the idea that the speaker has or hasn't experienced the action almost once in a life in the moment he is talking about. It is translated with the English form already in positive sentences or with ever and never in questions or negative sentences. It is called the experiencial aspect

- Ul ryb cax maj, I have already eaten fish, the speaker says he has experienced fish almost once. This kind of sentence never express the meaning of just which the adverb already can convey, this is expressed by the perfect particle.

- Ul ryb nat cax maj, I have never eaten fish, the speaker says he has never experienced fish in his life

- Ma ryb cax maj lo, Have you ever eaten fish?, the speaker asks someone whether he has ever experienced fish in his life

As in English these sentences are temporally located in the corresponding perfect tense, but they are marked with this aspectual particle, not with the perfect one.

If unexpressed, the time considered for the experience is the life of the speaker, past or future. The timespan can however be expressed and thus limited.

- Ul ryb tyk rok o nat cax maj, I have never eaten fish this year, the speaker says he has not experienced fish in the entire current year, but he might have eaten it before.

Use of modal particles

Modal particles express verbal modality, describing a quality about the action or the state expressed by the verb. English has only two modes (or moods) and it relies on modal verbs to express the same meaning of Qihep modal particles.

The absence of any modal particles conveys the basic idea of an action or a state, the reality form, without any added information about wish, obligation, possibility, etc.

Modal particles are placed after the aspectual particles and before the evidential particles. Since it is possible for more that one modal particles to be present in a verbal cluster, they can be added in the following order.

Vol conveys an idea of will, intent, intention or the idea for a planned action

- Tȳn lākȳt ta lā vol: He wanted to write a text (the subject had the intention to write the text, and it is almost sure he wrote it)

- Tȳn lākȳt fut lā vol: He is going to write a text (he has the intention and has planned to write the text)

Des conveys the idea of wish, desire, crave or hope, but it doesn't give any information about intention or planning

- Tȳn lākȳt fut lā des: He would like to write a text (the subject has the wishes to write the text, but we have no information if he has planned to do so)

- Tȳn lākȳt ta lā des: He wished to write a text (the subject has the wishes to write the text, but it seemed unlikely that he wrote it)

Without any specific subject or with a subject that cannot feel wish, it can express a general hope for the action to get real (something like the English subjunctive with may):

- Dōb lākȳt ā le fut lā fa des: May a good text be written (we hope that it will be this way)

Pos conveys an idea of ability, capability, that the subject knows how to do something, both an innate or a learnt capability.

- Tȳn nat lā pos: He cannot write (for example, because the subject is too young, and still does not know how to write)

Kra conveys an idea of a momentaneous ability, something that the subject can do in this moment, not a forever real capability.

- Tȳn nat lā kra sty: He cannot write (for example, the subject is too excited to write, too cold or too frightened, a momentaneous condition, but he knows how to write)

Ro conveys an idea of possibility, likelihood, potentiality of the action

- Tȳn lākȳt fut lā ro: He may write a text (it will be possible for the subject to perform the action and likely will do it)

- Tȳn lākȳt ta lā fa ro: He might have written a text (it was possible for the subject to perform the action and very likely has done it)

Da conveys an idea of allowance, permission, consent, approval

- Tȳn lākȳt fut lā da: He can write a text (the subject has received permission to do it)

- Tȳn lākȳt ta lā fa da: He was allowed write a text (the subject received permission to write, and very likely has done it)

Ōb conveys an idea of obligation, assigned duty or task, requirement

- Tȳn lākȳt fut lā fa ōb: He has to write down a text (the subject has the obligation to write, not doing it on his own initiative)

- Tȳn lākȳt ta lā ōb: He was compelled to write a text (the subject feels the obligation to write )

Nec conveys an idea of necessity, need, must

- Tȳn lākȳt lā nec: He must write a text (the subject feel the need, on his own initiative, to write)

- Tȳn lākȳt fut lā fa ōb: He needed to write down a text (the subject had the need to write the text, and likely has done it)

Vā conveys a causative sense, indicating that a subject causes someone or something to perform an action which was non-voluntarily (normally expressed in English by the auxiliary verbs let, make, get or have). Since a new performer of the action is introduced, the syntax of the sentence is reorganized. This will be analysed separately.

- Tȳn wa lākȳt rȳs in ta lā fa vā: She made him write a text

Kōm conveys an incohative action, marking a beginning action

- Tȳn lākȳt ta lā fa kōm: He began to write a text (the subject gets the action started)

Since the beginning action is inherently imperfective, aspectual particles with this modal particles refer to the aspects of the action of beginning, not the main action itself.

Fōr conveys an idea of hypothesis. It usually translate the concept of if, in the case that, maybe

- Tȳn lākȳt ta lā fa fōr: In the case he could have written a text (we express the hypothesis the subject would have performed the action)

Si conveys the idea of direct command, order, injunction. It usually translate the concept of English imperative mood, that is the subject is given the order to perform the action by the speaker:

- Ma lākȳt lā fa si: Write down a text (the subject is ordered to write)

It should be noted that the verb is not placed at the beginning of the sentence, but it is left in its normal position.

Differently from English, which for the second person left the subject unexpressed, the subject who has to perform the action is always expressed, expecially in the written language. Only in direct speech, in a strongly emotional situation for example, the second person can be left out:

- Lā fa si: Write! (This is an order given in a state of anger or anxiety, for example)

Also differently from English, which use the modal verb let to express imperative forms for other persons than the second one, these imperative forms are expressed with the simple modal particle si:

- Tȳn lākȳt lā fa si: Let him write down a text!

- Ul la lākȳt lā fa si: Let's write down a text!

Use of evidential particles

Evidential particles express the nature of the evidence for a statement, if evidence exists for the action stated or the attitude of the speaker in relation to the reported information.

The absence of any evidential particle does not imply that the speaker has actually witnessed the reported action, but only that this information is not relevant for the speech. There is however no evidential particle to express eye-witness of the action and this must be deduced by the context or lexically expressed.

Evidential particles are placed after the aspectual and modal particles and are always the last element of the verbal cluster.

Nah conveys the idea of reported action, with a stress on the fact that the information is reported by someone else, and that the speaker (and not the subject of the action) has not personally witnessed the action.

- Ńakvran sluh ta krāx fa nah: I was told that someone broke the vase (The speaker has not seen the action nor the broken vase, but someone else has told him about what happened)

Box conveys an idea of doubt about the tale. The action is reported by someone else, and the speaker (and not the subject of the action) has not eye-witnessed either the action or any evidence about it and according to him/her the action is doubtful.

- Ńakvran sluh ta krāx fa box: It seems/I was told that someone might have broken the vase (The speaker has not seen the action nor the broken vase, someone else has told him about what happened, but he express a serious doubt about the reported action)

Kap conveys an idea of deduction, since the speaker (and not the subject) has not personally seen the action, but he/she has seen some evidences about the action and he/she deduces the action from these evidences.

- Ńakvran sluh ta krāx fa kap: Someone has broken the vase (The speaker has not seen the action, but he has found and seen the broken vase, and makes his own deduction about what happened)

Negation

Negation is expressed by two negation particles. It is usuall considered as a part of the verbal cluster. The two particles are:

Nat, which negates every element or cluster placed after it. In the verbal cluster it is placed before the time particles:

- Ma pām ta sryńnēm fa, You bought the bread → Ma pām nat ta sryńnēm fa, You didn't buy the bread

The verbal cluster is not altered by the negation as in English.

The negation particle can however be placed outside the verbal cluster, negating thus a specific element of the sentence:

- Ma pām ta sryńnēm fa, You bought the bread → Nat ma le pām ta sryńnēm fa, It wasn't you who bought the bread

- Ma pām ta sryńnēm fa, You bought the bread → ma nat pām a ȳk le ta sryńnēm fa, You didn't buy the bread but meat

The negated elements are usually topicalized with le, but they are not mandatorily placed at the beginning of the sentence.

Pē, which express a prohibition, a forbiddance, thus the imperative form of the negative. It alters the verbal cluster, since the imperative modal particle is usually omitted.

- Ma pām sryńnēm fa si, Buy the bread! → Ma pām pē sryńnēm fa, Don't buy the bread!

This particle cannot negate other elements of the sentence.

As in English, double negatives are not allowed in Qihep. Only one word in the sentence can be negated:

- Ul nanvran ta piǵ fa: I saw nobody

- Ul ńakvran nat ta piǵ fa: I did not see anybody

Causative forms

Causative forms are peculiar, since they introduce a new argument, the causer, which causes someone or something to perform the action. The syntax of the sentence is therefore modified in English, since the performer is marked as the object and the causer as the subject, and the causative action is marked by verbs like to let, to make, to cause, to have, or to get.

Qihep uses a causative modal particle, vā added in the verbal cluster to mark the causative form of the verb. The performer of the action remain in its subject position, while the causer is introduced in the action as another member of the sentence and it is marked by the causative-agentive postposition in.

- Ul ta wā fa → Ul tȳn in ta wā fa vā, I cried → he made me cry

The causer is placed, like the other elements of the sentence after the direct object, but since it has an agentive roles, it is usually place before any other element. All other elements are placed in their regular positions.

- Ul la lākȳt tȳn in arbultsēd lā fa vā, Yesterday he made us write a text

Passive forms

Qihep verbs lack a passive form. In order to express a meaning similar to a passive forme, the object is moved to the first position of the sentence and is marked it with the accusative particle ā and with the topicalizing particle le. Since there is no real passivization, the agent of the action is not marked and is left in its subject position:

- Mew mīś ta fabej fa, the cat killed the mouse → mīś ā le mew ta fabej fa, the mouse was killed by the cat

If there is no agent, the subject is simply left unexpressed, and the use of the topicalizing particles becomes optional:

- Mīś ā le ta fabej fa, the mouse was killed

As in English, this the way to express the impersonal subject of other languages:

- Qīxēp ā tykmeś xēp, Qihep is spoken here, in French: ici on parle qihep, in Italian qui si parla qihep, in German man spricht Qihep hier

Even if it is possible to form a passive adjective with the suffix -sy, this is never used as a verb, but only as an adjective.

- Mew fabejsy mīś ta cax fa, The cat ate the killed mouse

Locative verbs

Qihep lacks generic locative postpositions (the locative postpositions usually convey well defined and clear locative meanings, like near or towards). This is because there are locative verbs, which express the meaning of location or movement. This kind of verbs treat the location or the destination of the movement as their object, so they are marked by the simple position in the sentence.

- Ul xūcmeś ńik bultsēd bim sōl, I go to school every day

- Tȳn la Itālia ta sōlǵīv sōl, They used to live in Italy

- Ma wū stā lo, Where are you?

When a verb can express both the source and the destination of a movement, the source takes the place of the indirect object, while the destination is still the object of the verb.

- Ul frīnmeś dūm ta bim fa, She went home from the market

When the location or the destination need to be marked to avoid ambiguity or topicalized, they are marked with the object particle ā.

- Wū ā le rȳs stā lo, She is in which place?

When the source of movement needs to be marked to avoid ambiguity or topicalized, it is marked by postposition ud.

- Ul la Itālia ud ta qin fa, We came from Italy

When we want to express a locative expression in a sentence with another non-locative verbs, we have to use a relative sentence with a locative verb.

- Rōma ā dūqin ǵa dī ma la ā le ul la dōb topīk, Welcome to Rome!, (lit. We receive well you that you have come to Rome)

- Tȳn la nār sryńmeś ā stā sty dī xūckreśmor ta piǵ fa, They saw the professor in that shop (lit. They saw the professor who was in that shop)

| Locative verbs | |

|---|---|

| Verb | English |

| stā | to be in |

| bim | to go to |

| dōlbim | to go down to, to descend to |

| dūbim | to arrive to, to reach |

| unbim | to go in, to enter |

| vybim | to go out, to exit |

| qin | to come to |

| dōlqin | to come down to, to descend to |

| dūqin | to arrive to, to reach |

| unqin | to come in, to enter |

| vyqin | to come out, to exit |

| sōlǵīv | to live in |

Questions

Direct interrogative sentences, or questions, are built differently from English. The position of every word is unaltered and the entire sentence is marked by the interrogative particle lo at the very end of the sentence.

- Tȳn kōr sa sty → tȳn kōr sa sty lo, he is reading a book → is he reading a book?

The word order remains the same even with interrogative pronouns or adverbs, which are placed in their regular position; they can be regularily fronted by using the topicalizing particle le, but the meaning expressed is slightly different, since it is topicalized.

- Ma wū ta sryńnēm fa lo, What did you buy?

- Wūmeś le ma qem ta sryńnēm fa lo, Which is the place where you bought them?

If the question is followed by a subordinate or a coordinate clause, the particle lo is placed at the end of these clauses, if their meaning is part of the question.

- Ma ul woroh kreś fa ul tyk trojkȳtxep āśvor fa le lo, Would you give me the keys to open this door?

The basic answers to a yes/no question are:

- Dā, yes

- Nā, no

The verb "to be"

Qihep lacks a verb meaning to be in the form that English or other European languages have. It has instead more constructions:

With the meaning of locative to be, to find yourself, the locative verb stā is used, according to the rules of locative verbs.

- Rȳs dōm mo stā sty, She is at home right now

With the meaning of existencial to be, that is to be there, the verb ē is used.

- Dē la ē sty, There are many children

With the meaning of qualitative or attributive to be, that is X is Y, there are no verbal form available. Adjectives or apposition are simply placed in the verbal position.

- Tȳn jenmor, He is a doctor

- Ul la jūn, We are young

The adjectives are treated like verbs in this case, and they take the role of the core of the verbal cluster, taking the necessary grammar particles:

- Ul la nat jūn ǵa, We are not young anymore

Also appositive names can be treated like verbs, but the sentence is usually transformed with other verbs, so that at the core of verbal cluster there is a real verb.

- Tȳn ta jenmor sōl, He used to be a doctor → Tȳn jenmor bā ta mar sōl, He used to work as a doctor

Subordinate clauses

Qihep lacks proper subordinating particles, as it considers subordinate as phrasal elements of the main sentence. Even if it might be possible to place this phrasal element inside the sentence, it is usually placed in the beginning or at end of the sentence, i.e before of after the main sentence.

Subjective and objective clauses

Subjective and objective clauses are marked respectively with the grammar particles for the subject, wa, and for the direct object, ā, placed after the verbal cluster. If they are placed before the main sentence, they are mandatorily marked with the topicalizing particle le, while if they are placed after the main sentence, le is not mandatory.

- Ma qin ǵa wa le śōn, it is beautiful that you have come

- Tȳn kāg fa upbultsēd klōj bim fa ā, he said it will rain tomorrow

Relative clauses

Qihep lacks proper relative pronouns, as it considers relative clauses as phrasal specifying elements, like a genitive phrasal element. The relative sentence is placed before the noun it specifies and it is marked by the genitive particle dī.

There is some difference, however, according to the role that the specified element plays in the relative clause:

When the specified element is the subject of the relative clause, it can be dropped, but the object must be mandatorily marked with the object particle ā:

- Ul tȳn Qīxēp ta xūckreś fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher who taught Qihep

- Ul Qīxēp ā ta xūckreś fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher who taught Qihep

When the specified element is the object of the relative clause, it can be dropped, and the subject can be marked with the subject particle wa, but this is not mandatory:

- Ul ma tȳn arbultsēd piǵ fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whom you saw yesterday

- Ul ma wa arbultsēd piǵ fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whom you saw yesterday

- Ul ma arbultsēd piǵ fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whom you saw yesterday

When the specified element is the indirect object of the relative clause, the sentence is expressed as normal, but the indirect object pronoun is expressed by the corresponding personal pronoun and it can be marked by the dative particle ū, and the direct object with the object particle ā, expecially in case of ambiguity:

- Ul ma tȳn kōr ta kreś fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whom you had given the book

- Ul ma tȳn ū kōr ta kreś fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whom you had given the book

- Ul ma tȳn ū kōr ā ta kreś fa dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whom you had given the book

When the specified element plays one of the other roles in the relative clause, the sentence is expressed as normal, the element is expressed by the corresponding personal pronoun and it is mandatorily marked by the corresponding particle:

- Ul ma tȳn ab ta xēp sty dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whom you were talking about

The same process is used when the specified elements is in genitive construction (expressed in English by the relative pronoun whose) in the relative clause. The specified element is expressed by the corresponding personal pronoun and it is mandatorily marked by the genitive particle dī:

- Ul tȳn dī kōr śōn dī xūckreśmor ta unqum fa, I met the teacher whose book is beautiful

Temporal clauses

There are two kinds of temporal clauses: those that refer to a single or precise moment, expressed by the word dān, moment, and those that refer to a longer period of time, expressed by the word tsēd, time.

This word are marked by the corresponding temporal grammar particles o, on, u, bī, śi, ńo, and placed at the beginning or at the end of the sentence with the topicalizing particle le. The possibile temporal constructions are:

- Dān o le (in the moment when) or tsēd o le (in the period when) = when, while

- Dān u le (from the moment when) or tsēd u le (from the period when) = since

- Dān bī le (until the moment when) or tsēd bī le (until the period when) = until

- Dān śi le (before the moment when) or tsēd śi le (before the period when) = before

- Dān ńo le (after the moment when) or tsēd ńo le (after the period when) = after

The meaning of the construction is usually specified by the aspectual particles of the verb:

- Dān o le tȳn vybim fa tȳn tȳn la ta unqum fa, When he went out, he met them.

- Dān o le tȳn nōbim sty tȳn tȳn la ta unqum fa, While he was walking, he met them.

Purpose clauses

There are two ways of expressing a purpose clause:

1. The supine verbal suffix -vor is used and the clause is usually but not mandatorily marked by the topicalizing particle le after the verbal cluster. The verbal form can be specified by modal and aspectual particles, but time particles are usually not used.

- Ul qin ǵa ul ma śpomvor fa le, I've come to help you.

2. The purpose clause is marked by the construction tsel vor le, which can be placed at the beginning or at the end of the clause, and all verbal particles are used.

- Ul qin ǵa tsel vor le ul la śpom fa, I've come to help you.

Causative clauses

Causative clauses are marked by the construction prīc par le, which can be placed at the beginning or at the end of the clause.

- Xup nēmvran ta vēbeg fa prīc par le tyn la ā piǵ fa, the two thieves ran away, because they saw them.

Modal clauses

Modal clauses are marked by the construction cin bā le, which can be placed at the beginning or at the end of the clause.

- Ma kīn fa si cin bā le ma wiś, Do as you want!

Indirect interrogative clauses

Indirect interrogative clauses are marked in two ways:

If there is an interrogative pronoun or adverb, the sentence is placed before or after the noun without the interrogative particle lo:

- Ul nat snā wē ta vybim fa, I don't know who went out

If in the corrisponding direct question there is no interrogative pronoun or adverb, the sentence is placed before or after the verb with the interrogative particle lo in the right place:

- Ul nat snā rȳs ta vybim fa lo, I don't know if she went out

Indirect interrogative clauses can be marked with the object particle ā or the topicalizing particle le, but this is not mandatorily and they are usually used only in case of ambiguity, especially when the interrogative clause is placed before the main sentence.

- Ul nat snā rȳs wū ta kāǵ fa ā, I don't know who went out

- Ul tȳn ńakqem ta kāǵ fa lo ā le tȳn la nat snā , Whether I told him anything, they don't know

Conditional clauses

Conditional clauses are not explicity marked with a grammar particle nor with the topicalizing particle, but by the modal hypothetical particle fōr. Two sentences with verbs marked with fōr are meant as a conditional clause and its main clause:

- Tȳn la dōm fut bim fōr, ul tȳn la e fut bim fōr, If they went home, I would go with them.

- Tȳn do ta snā fa fōr, tȳn ma ta śpom fa fōr, If he had know, he would have helped you

The hypothetical particle fōr strictly marks an hypothesis, so it is not used when it's not an hyphotesis, but a state of fact:

- Bul tykmeś stā, pū nat, If there is the sun, it is not night

When the meaning of if is more temporal than an hypothesis, the clause is meant as temporal and not conditional:

- If you come, you'll see him (= When you come), Dān o le ma fut qin fa, ma tȳn fut piǵ fa

- If there is the sun, it is not night (= When there is no sun), Tsēd o le bul tykmeś stā, pū nat

When in the main clause there is an imperative form, the hypothetical particle can be dropped.

- Ma ȳd fut piǵ fa fōr, ma vēbeg fa si!, If you saw a snake, run away!

Lexycon

Dictionary

- Main article: Qihep-English dictionary

Everyday lexycon

- Eh: Hi, Hello

- Tū dōb des: Good morning (lit. May the morning be good)

- Lū dōb des: Good afternoon (lit. May the afternoon be good)

- Ān dōb des: Good evening (lit. May the evening be good)

- Pū dōb des: Good night (lit. May the night be good)

- Ma uś fut ro: Bye (lit. May you be fine)

- Ul (la) ma (la) dōb topīk: Welcome (lit. I/we receive well you)

- Ma dī ǵīv wūcin lo: How are you? (lit. How is your life?)

- Dōb dā, Well (lit. Good yes)

- Dōbdōb dā, Very well (lit. Very good yes)

- Ēp, Thank you

- Ēpēp, Thank you very much

- Tyk nanqem: You're welcome (lit. This is nothing)

- Ma wūcin ńīm lo or Wū ma dī ńīm lo: What is your name?

- Ul ... ńīm or Ul dī ńīm ...: My name is ...

- Ma wō rok smel ǵa lo: How old are you? (lit. How many years have you grown?)

- Ul ... rok smel ǵa: I am ... years old (lit. I have grown ... years)

The seasons of the year - Roktsēd

| English | Qihep |

|---|---|

| Spring | Argōtsēd |

| Summer | Gōtsēd |

| Autumn Fall |

Arbȳtsēd |

| Winter | Bȳtsēd |

States of the world - Dīn elān la

- Main article: States of the World (Qihep)

The names of the states of the world are usually loanwords, so they are expressed by phonetic compounds, with normal syllables used for their phonetic value instead of their meaning. They are thus usually written with an underline. Names like state, kingdom, federation or democratic are not used directly but they are translated and not underlined.

The names of the states can be used as the relative adjective, and can be compounded to express the name of the inhabitants and of the related language.

- Itālia: Itālia vranvran, Italian population, Itāliavran, an Italian, Itāliaxēp, the Italian language

Some states have however developed an alternative adjectival form. This form will be used for the compound words, if they refer to the culture, while the name of the country will still be used when referring to the state.

- Doiclān: Doiclān vranvran, Doiclānvran, an inhabitant of Germany, but doicvran, a person speaking German, doicxēp, the German language

Dialogues

- Main article: Qihep dialogues

Texts

Lord's prayer

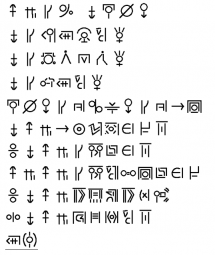

| Logographic script | Latin transcription |

|---|---|

| ul la dī pāp, ma kōpdīn stā ma dī ńim ā śkedskyt des ma dī horvranmeś qin des ma dī wiś ā skyt des kōpdīn stā dī do i grūn stā dī do tykcin ma ul la tykbultsēd pām kreś fa si ī ma ul la dī smūś vorkreś si ul la ul la dī smūśmor mēmcin vorkreś fa ī ma ul la togrēxkȳt to pē mūh yt ma ul la śluk ud vrīskyt si āmen |

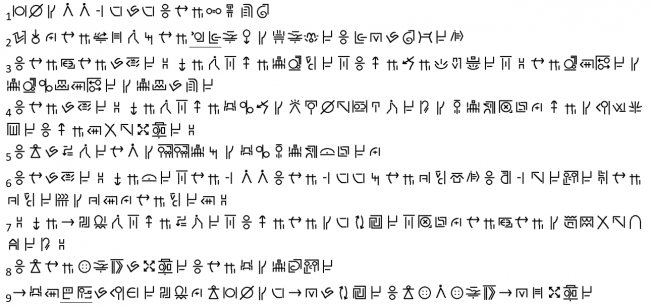

Babel text

1. tsāl dīn dī vranvran mē xēp rā xēp ī tȳn la mēm dum nūt sōl

2. tsēd o le tȳn la xīs ud qin sty tȳn la Śinār lān stā dī sbēnlān qum fa ī nārmeś rā sōlǵīv fa kōm

3. ī tȳn la drug tȳn la rā kāǵ fa "ma la qin si ul la trojsās skyt fa si ī ul la qem la pīr ō qōc fa si" tȳn la sās ā skām fa dī trojsās i kāx ā skām fa dī trojkāx rā nūt fa

4. ī tȳn la rā kāǵ fa "ma la qin si ul la byl i qem dī fīp kōpdīn fut dūbim fa pos dī fītrojkȳt tsel vor le ul la dī ńīm snāsy bly fa ī ul la ā nat fut rasjēq fa"

5. ī Pō rā dōlqin fa tȳn vran dī denden troj sty dī byl i fītrojkȳt piǵvor fa le

6. ī tȳn rā kāǵ fa "ma la piǵ fa si tȳn la mē vranvran ī tȳn la mē xēp xēp sty tȳn la do skyt ǵa kōm ī ńakmē tȳn la fut fajan fa kra tȳn la do skyt fa vol dī do ā le tȳn la skyt fa ā"

7. "ma la tyk prīc par qin si ul la dōlbim fa si ī ul la tȳn la dī xēp obmiś fa si tsel vor le tȳn la drug tȳn la dī xepsvūk nat fut enēm fa pos"

8. ī Pō tȳn la ńik lān to rā rasjēq fa ī tȳn la byl dī trojtān jan fa

9. tyk byl ā Bābēl rā ńīmkreś fa prīc par le Pō tsāl dīn dī xēp tykmeś rā obmiś fa ī Pō ńik vran ńik lān to tykmeś ud rasjēq fa

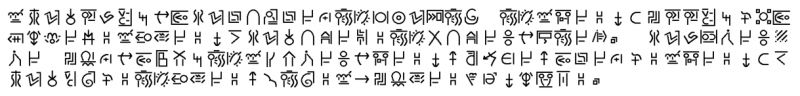

The Ant and the Grasshopper - Ań i pejūǵ

Ań gōtsēd o jy rā mar sty tȳn cāx bȳtsēd vor epīkvor fa le. Pejūǵ tsāl bultsēd on pej rē. Pejūg ań ū ka fa "ma wūprīc jyjy mar sty lo mā cāx ā mo qum fa ro". Ań rikāǵ fa "ma up bȳtsēd o enēm fa kra". Pejūǵ nat enēm fa ī tȳn nu pej fa kōm ī ań nu mar fa kōm. Bȳtsēd rā dūqin fa ī nev bim fa. Prīc par le tȳn caxnēccum sty pejūǵ ań dī dōm bim fa ī tȳn ka fa "ma ul ńakqem kreś fa ul caxvor fa le lo". Ań ka fa "ma wū ar gōtsēd o skyt sōl lo". Pejūǵ rikāǵ fa "ul ta pej sōl". Ań tyk prīc par kāǵ fa "dōb dā ma mo tsā si"

The Fox and the Grapes - Ew i el

Caxnēcim ew ǵe el rā piǵ fa tȳn yp rē yt tȳn qem nat fanēm kra. Dān o le tȳn vēbim sty tȳn mī fa "ul qem nat wiś qem nat smēl fa". Fatsel ā nat dūbim fa kra dī tȳn la obstātān vīnkreś fa sōl.