Stilio

| Stilio slashuru | |

|---|---|

| Species: | snakes and snake-like reptiles |

| Credits | |

| Creator: | Robert Marshall Murphy |

| Created: | 2012 A.D. |

Parseltongue (in this article) refers to Stilio, a reconstructed form of Parseltongue. A script for this language is forth-coming. This language a unique morphosyntactic alignment, and defaults to SOV word order. It is, however, strongly non-configurational, except verbs usually end a phrase and always end an utterance.

Phonology

Snakes have vastly simplified mouths compared to human-being. We are capable of making every sound they make, though some are easier than others. Snakes have no lips, but their labial scales can contract and produce something like "lip-rounding". Labialization is very important is Parseltongue. Their palate is occupied with the vomeronasal organ (Jacobson's organ), which acts as a sense of smell. Snakes have no uvula. Their glottis is where our pharynx is, but it can move aside when eating large prey. They have no epiglottal region.

Sentient and non-sentient snakes hiss their entire volume of air without interruption, so a Parseltongue utterances cannot be longer than about ten seconds. Stops are typically initial in a verb. Whatever vocal-cords they are graced with by magic, snakes cannot speak very loudly or vary pitch beyond very low frequencies.

Given their anatomy, even with the aide of magic, Parseltongue

- has no labial consonants

- has no retroflex consonants

- has no palatal or alveolar-palatal consonants

- has no uvular, pharyngeal, or epiglottal consonants

- has no voiced consonants

- is all spoken in creaky-voice

- has no corarticulated consonants

- of the clicks, has only the dental and the lateral

- may begin an utterance with a stop, but they are rare elsewhere in speech.

- affricates are common

- must end an utterance with a sibilant/fricative or - less commonly - a vowel

- has ejective forms of the stops and affricates

- contrasts lip rounding on most consonants

Consonants

| Consonants (sans Labializations and Affricates) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||||||

| Central | Lateral | Central | Lateral | |||||||||||||

| Nasal | n | g | ||||||||||||||

| Unaspirated Stop | t | k | ||||||||||||||

| Ejective | f | q | ||||||||||||||

| Click/Tap | / | ? | \ | |||||||||||||

| Fricative | d | s | z | c | x | l* | ||||||||||

| Approximant | r | l | y | l* | h | |||||||||||

Because snakes use a wide range of glottis motion instead of changing vocal fold pitch, there are two versions of all fricatives and approximants. Humans can best approximate this change by tightly rounding their lips. Some humans find this exceedingly difficult to with /θ/. This sound is best approximated by rolling (also called curling) the tongue and passing air through as thin an opening as possible. Most English speakers round their lips anyway when saying /r/ and /ʃ/ someone, so great care must be taken. Snakes don't appear to mind if sᵂ produces some whistling.

A history of Latin alphabet orthography has given rise to the system as presented in the tables. Some consonants are exactly the same as IPA notation: t k x s l h. Others require some thought: n for /n̥/, g for /ŋ̊/, f for /t'/, q for /k'/, d for /θ/, c for /ʃ/, z for /ɬ/, r for /ɹ/, y for /ɰ/. The dental and lateral clicks, and the alveolar flap receive non-letter symbols: \ / ?.

All affricate possibilities are realized in Parseltongue, though most are very rare. Parseltongue does not distinguish between affricate and non-affricate pairs, so the tie-bar is not commonly written, even in IPA. The possibilities are: td ts tc tz kx fd fs fc fz qx.

The letter h does double duty. It indicates the glottal fricative when word-initial, word-final, or following a vowel. Otherwise, it indicates heavy aspiration. w indicates rounding/labialization and is written as a superscript whenever possible. Many English speakers are unaware that they always round /ʃ/ and word-initial /ɹ/, so great care must be taken. Notice too that yᵂ means /ʍ/

Allophony

- k/x/q/kx/qx + l > ɫ

- k/x/q/kx/qx + z > ʟ̝̊

Vowels

| Vowels (in IPA) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Center | Back | ||||||||

| High | i · y | u | ||||||||

| Mid | e · ø | o | ||||||||

| Low | æ | ɐ | ||||||||

The Parseltongue system of vowels is a simple set of eight unique sounds. The "resting vowel" (like English schwa) is /ɐ/, but snakes more often "gap" with /s/. The sometimes despised "ash" (/æ/) is not rare in Parseltongue. There are no diphthongs.

Parseltongue is written using only i e æ a o u. a stands for /ɐ/. /y/ (ï) is written iᵂ and /ø/ (ë) is written eᵂ.

There are two non-phonemic sounds that snakes are readily capable of making, the trilled 'r' and the glottal stop. However, /r/ is a highly erotic sound which no snake would make in polite company, and stopping the flow of air during an utterance is indicative of sickness or eating.

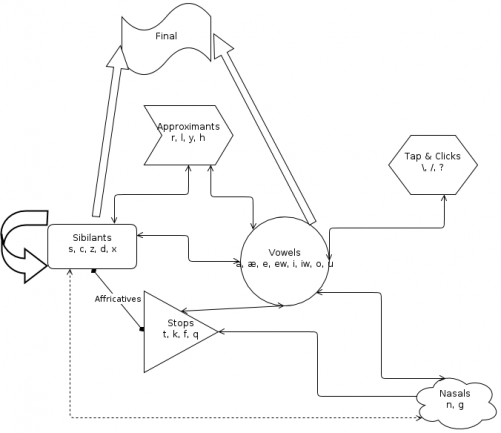

Phonotactics

Parseltongue is extremely difficult to analyze phonotacticly. Even with enunciating as one would to a fool or simpleton, snakes never cease the continuous airstream. Syllable boundaries, therefore, are somewhat arbitrary. Snakes we interviewed regard this as an unimportant, human problem, akin to transcribing choking or sneezing. For our purposes, we should regard Parseltongue syllables as capable of having either a vowel or a fricative in the nucleus. A fricative (in the onset or in the nucleus) may be long or short, labialized or not. A syllabic fricative may be preceded by a stop, and hence, part of an affricate. It may also be preceded by an approximant or another fricative. Open syllables, in this case, are common. A short fricative or a nasal can be analyzed as the coda of a fricative-nucleus syllable.

If a vowel is the syllable nucleus, it may be preceded by a tap, click, either nasal, a stop (which may be preceded by a fricative), a fricative, an affricate (which may be preceded by a fricative) or an approximant (which may be preceded by a stop or a fricative). The coda of a vowel-nucleus syllable may be a nasal (which may be followed by a fricative), a fricative, l or h, or it may be left open. Clicks and taps may only follow an open, vowel-nucleus syllable.

It is very important to note in the difference between long and short fricative - which might be regarded as geminate - depending on where they occur in an utterance. Quite inhumanly, a fricative-chain may go on for an entire utterance, with some being short and others long.

Grammar

Nouns

Parseltongue is exceedingly pro-drop, like Japanese or Korean. Speakers often state the topic and then rely on context to make things clear. There are four 'core' cases - called Nominative, Volitional, Illustrative and Stative - and five 'oblique' cases - Dative, Possessive, Partitive, Genitive, and Ablative. The core cases form mostly by ablaut, the obliques mostly by suffixing. The definite article is a prefixed /s/, while indefiniteness is marked in the verb.

| Case | Paradigm |

|---|---|

| Nominative | kac |

| Volitional | qac |

| Illustrative | keᵂcᵂ |

| Stative | qeᵂcᵂ |

| Dative | kacgæ |

| Possessive | kaca |

| Partative | kacæ |

| Genitive | kaccᵂeᵂ |

| Ablative | keᵂcᵂa |

There are four noun declensions (a->eᵂ->æ ; e->cᵂ->o ; i->iᵂ->u ; s->sᵂ->dᵂ)

Pronouns

There are 'dummy' pronouns which are nearly contentless in meaning. However, 'measure words' can also be used as pronouns, with or without numbers attached.

| Case | Form | Ex. |

|---|---|---|

| N | dss | Nothing exploded. |

| V | tdss | No one attacks him. |

| I | dsᵂsᵂ | Nothing here is alive. |

| S | tdsᵂsᵂ | No one has been bitten. |

| D | dssagdᵂ | Nowhere is that allowed. |

| Po | dssh | No one's face is hot. |

| Pa | dssdᵂ | There is no one here. |

| G | dsshsᵂ | I am a snake of nowhere. |

| A | dsᵂhs | Put a living upon nothing. |

Verbs

All verbs have a lexically contained expectation for which case the subject will be in. Hence, all verbs are active or passive and volitional or non-volitional by default, which will also indicate paradigm it follows. Active verb endings are suffixed, passive prefixed. Volitional verb endings are sibilant heavy, non-volitional vowel heavy.

Verbs inflect for an astronomical eight persons:

| Person | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| -1 | Universal negation | "No one eats himself." |

| 0 | Indefinite | "Someone ate the prey." |

| ½ | dim. part of ego | "Me (my tail) is coming." |

| 1 | Ego | "I ate the mouse." |

| 1½ | a.k.a. 2 inc. | "We (you and I) are friends." |

| 2 | Interlocutor | "You are handsome." |

| 3 | Near other party | "She is our daughter." |

| 4 | Obviative | "He bit her." |

As with nouns, Parseltongue does not typically mark number. Tense is assumed or conveyed via adverbs.

Aspect is either imperfective or perfective. There are three mood: Indicative - for independent clauses; Subjunctive - for dependent clauses; and Illocutionary - for magical or imperative clauses. The subjunctive is very plain, conjugating for only aspect, but not person or evidentiality.

All indicative/independent verbs in Parseltongue must be marked for evidentiality. Snakes senses are (in decreasing order of assuredness):

- Taste/Smell

- Snakes extend their tongues into the air/water and pull "smells" into their mouths, where their "noses" (Jacobsen's organs) are. This gives them a very refined and directional sense. Knowledge obtained this way is the most certain and so is most analogous to human's "I see" or "I know".

- Heat/IR

- Snakes have special sensors where other animals' "noses" would be which detect heat or Infra-red radiation. Snakes report not "seeing" a field - as humans do with sight - but "feeling" the nearness and/or warmth of things. This is most akin to a human saying "I feel like you are ..." or "I sense not everyone in the room agrees with ...".

- Hear/Vibration

- A snake's entire body functions like an "ear", sensing vibrations. This knowledge is very accurate, but because it comes from their whole body (not just their head) it is more like "gut knowledge". Magic causes snakes internal ear to hear external speech.

- Sight

- Most snakes have poor vision, with a majority not being binocular. This mood is used metaphorically as a person would say, "I suppose" or "I guess".

Idioms

- (like a) Human's face in the nose

- "It's self-evident." Snakes' faces are unreadable, but they generally know how to read human body language, mainly through smell and temperature sensing. Smells are "in one's nose" because smell samples are brought into the mouth by the tongue and placed upon the Jacobsen's organ.

- This must pass over the nose

- Food is passed over the Jacobsen's organ as it is eaten. If something is noxious, to eat it would be unbearably intense. Snakes say this meaning "It's too awful" or "I don't want to!"

- Passing over roughness aids molting

- "What doesn't kill you makes you stronger in the end."

- Some have eggs inside, some have eggs outside

- "Different strokes for different folks." Some snakes have pouches for their eggs to hatch inside their bodies, giving the appearance of live births. Many snakes do not.

- I am the venom.

- Not all snakes are poisonous, but all snakes spur themselves on to overcome fear and strike out (often metaphorically) by willing themselves to be their own venom. "I can do this!"