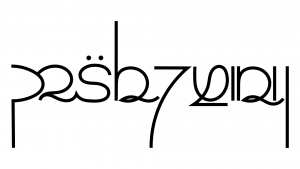

fantazkirain

fantazkirain [ˈfän.täzˌki.ɾäɪn] (formerly known variously as fenhlkirain or viossakirain) is a writing system designed by Fenhl, originally for Viossa but now serving as a generic script. The name is Viossa for “fantasy letters” (or “fantasy glyphs”, since the script is not strictly an alphabet). It was originally created in 2015, with small additions made over the years to accomodate some phonemes and clusters that rarely or don't occur in Viossa, to coin new logograms, and to extend and codify the ligature system. It was designed to superficially resemble a writing system that could have naturally formed in a Viossa-speaking community, and thus takes vague inspiration from various writing systems including Greek, Latin, Cyrillic, Hiragana, Wanya (in turn inspired by Cyrillic, Greek, and Latin), Chinese, Arabic, Batunurisi (in turn inspired by Futhark (via Wyunurisi), Canadian Aboriginal syllabics, and Arabic), and the Tengwar. It is intended as a calligraphic script written with a ballpoint pen.

Overview

Much like Latin and Greek, fantazkirain is written in lines from left to right and has a base height for small letters as well as ascenders and descenders. There are two sets of basic units:

- kirain (“letters”) are roughly phonemic units, though some represent sequences of more than one phoneme, and many irregularities exist. Most kirain are small letters but some have ascenders and/or descenders. They can be written with slight slants or other minor variations, and often form ligatures with each other.

- kotoba (“words”) are logographic units whose usage is entirely optional. All kotoba extend from the baseline to slightly below ascender height, much like Latin or Greek capital letters. They all have the same width, and none have descenders or form ligatures.

There are also diacritics that can be attached to kirain, called obakirain when above a letter or unakirain when below. Some kirain change shape depending on where diacritics are attached, and other kirain can't have diacritics attached on one or both sides. If a diacritic can't be attached to a preceding letter, it is instead attached to a Le, which functions as a null character similar to the vowel carrier tengwa.

Kirain

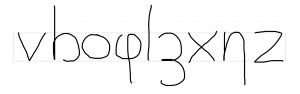

The canonical order of the kirain is:

| # | Name | Phonetic value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Či | tʃi, tʃɪ[note 1] |

| 2 | Cu | tsɯ, tsu, tsy, tsʊ |

| 3 | Krais | [note 2] |

| 4 | Es | s |

| 5 | Te | t |

| 6 | Jin | dʒ[note 3] |

| 7 | Ve | v |

| 8 | Nihonossa U | ɯ |

| 9 | A | ä |

| 10 | Ye | i, ɪ[note 4] |

| 11 | Le | l, ə |

| 12 | O | o, ɔ |

| 13 | U | u, y, ʊ |

| 14 | Una E | ɛ |

| 15 | Oba E | e |

| 16 | Ke | k |

| 17 | Ge Tolka | ɡ |

| 18 | En | n |

| 19 | Be | b |

| 20 | He | x, h |

| 21 | Re Haji | r, ɾ |

| 22 | Fe | f |

| 23 | Me | m |

| 24 | Daag | d[note 5] |

| 25 | De | d |

| 26 | Eŋe | ŋ |

| 27 | Se | se |

| 28 | Na | nä[note 6] |

| 29 | Re Mellan | r, ɾ |

| 30 | Fura O | ø |

| 31 | Še | ʃ |

| 32 | Ze | z |

| 33 | Ryu | ɾj |

Notes

- ↑ The Viossa consonant cluster [xj] is written as Či followed by Ye.

- ↑ Krais generally represents coronal fricatives but the exact phonemic value depends on the language being written and the position in the word. When writing Viossa or Wanya, it represents [s] in syllable onsets and [ʃ] in codas. In German, it represents the “non-sharp S”, i.e. [s] or [z], while it represents [θ] or [ð] in English and other languages that have these sounds.

- ↑ Jin is somewhat of a mix between a letter and a logograph, usually representing [dʒ] but also representing the Viossa morpheme "-jin" (“person”) in a word that's otherwise written with kirain. When writing other languages, it can be used similarly, e.g. to write the “-er” in English “gardener” or the „er_in“ in German „Gärtner_in“.

- ↑ Ye can also represent [r] or [ɾ] (or other rhotics depending on language) when immediately following a syllable nucleus or at the end of a morpheme, or the entire Viossa consonant cluster [ndr].

- ↑ Daag can represent [d] in morpheme-initial position, [nd] in morpheme-medial position, [nt] in morpheme-final position, or the Viossa morpheme "-daag" (“day”), with rules analogous to those for Jin.

- ↑ Na can also represent the Viossa morpheme "-yena"/"-ena" (a passive form), which unlike "-jin" and "-daag" does not have a kotoba.

Diacritics

The following diacritics are used:

- dot above

- Turns a Či into [tʃ]

- Turns a Jin into [ʒ]

- Turns a Be into [bɾ] or [br]

- Turns a Ge Tolka into [kä]

- bar above

- Turns a Cu into [ts]

- Turns a Še into [ʃi] (not used if the [ʃ] can be written as a Krais)

- two dots above:

- Followed with a Ye to make [j], or with an O to make [w]

- Turns a Še with bar above into [ʃj]

- A Daag with two dots above is followed with a T to make [nt]

- bar below:

- A way to write [l] that is preferred over the kirain Le whenever possible, even across morpheme boundaries

- Turns a preceding Ge Tolka or combining g into [k]

- three dots below:

- This is the reduplication mark, signifying that the previous vowel or consonant is long.

- There is also a separate unakirain called the excessive reduplication mark which has some variety in exact appearance but generally starts with a horizontal stroke followed by a curved or zig-zagged downward stroke. It is roughly equivalent to repeating a letter several times in colloquial English.

- strikethrough:

- Turns an A into [æ] or [a]

- Turns a Be into [p] (or a Be with dot above into [pɾ] or [pr])

- combining g:

- A way to write [ɡ] that is preferred over the kirain Ge Tolka whenever possible, even across morpheme boundaries

These may be stacked, and are then read from the inside out, i.e. the lowest obakirain or the highest unakirain are read first. Strikethrough is considered neither obakirain nor unakirain and always read first. Combining g is considered an obakirain and/or unakirain depending on its shape, which in turn depends on the kirain it's attached to, as it's generally written by extending the kirain's final stroke with a hook above or loop below:

- Written as obakirain (hook) after Či, Krais, Ye, word-medial-form En, unakirain-form En, Daag, Eŋe, Fura O, and Še, except if the kirain already has another obakirain or the combining g would be part of [k] after a kirain that cannot have unakirain.

- Written as unakirain (loop) after Es, Te, Jin, Nihonossa U, A, Le, O, U, Una E, Oba E, Ke, word-initial-form En, ligature En, He, Fe, De, and Ryu, except if the kirain already has another unakirain.

- Never written (Ge Tolka used instead) after Cu, Ge Tolka, Be, Re Haji, Me, Se, Na, Re Mellan, or Ze.

- After Ve, all three variants are allowed, though obakirain form is considered the typographical standard.

Letter variants and ligatures

Note: combining g is not considered an obakirain or unakirain in this section, as its behavior has been specified above, and kirain generally do not use variant forms for it.

- Cu:

- A Cu whose only obakirain is a single bar retains its ascender, with the bar striking through it but still being longer to the bar's right than to its left.

- A Cu with any other obakirain (e.g. in [tsuj]) or multiple obakirain (e.g. in [tsj]) loses its ascender.

- Es loses its descender when it has unakirain.

- Te has a variant form when it has obakirain. This form can also be used to make space for unakirain on the Te when an adjacent kirain is also thin and has unakirain, or when the Te with unakirain follows a variant form A.

- Jin:

- Cannot have unakirain.

- A logographic Jin after a kotoba or foreign full-height glyph is written as the kotoba Person instead.

- Ve:

- Depending on writer style, the top right to bottom left stroke can be reversed and connected to the start of a following Jin, Ve, Nihonossa U (in variant form; see below), variant form A (see below), Ye, O, U, Fe, Še, Ze, or Ryu. Typography does use this ligature if technologically feasible.

- Nihonossa U:

- Has a variant form that is attached to a preceding Krais, Te, Ve, variant form Nihonossa U, variant form A (see below), Ye, Le, O, U, Una E, Oba E, Be, He, Fe, Daag, Eŋe, Na, or Fura O, or unakirain form combining g.

- Cannot have unakirain.

- A:

- Has a variant form that is attached to a preceding Krais, Te, Ve, Nihonossa U (including variant form), variant form A, Ye, Le, O, U, Una E, Oba E, Be, He, Re Haji, Fe, Me, Daag, De, Eŋe, Na, Fura O, Še, or Ryu, or unakirain form combining g, but only if the A has no strikethrough.

- A bar below a variant form A (or below such a bar) has a slightly curved shape to be parallel with the bottom of the kirain (or bar) above it.

- Ye following variant form A cannot have unakirain.

- Le cannot have a bar signifying [l] below it.

- Ge Tolka:

- Has two different forms with a bar below it. If the bar is used to turn it into [k], the kirain and the bar are written in a single stroke which is sometimes considered a separate kirain Ke. If the bar represents [l], the kirain gains a curved ascender on the right.

- Cannot have obakirain except in Ke form or if its first obakirain is a dot above. The [ɡl] form cannot have obakirain at all.

- En:

- Has a variant form when it has unakirain. This form can also be used to make space for obakirain on the En when an adjacent kirain is also thin and has obakirain.

- Has a different variant form when not word-initial and without unakirain.

- Forms a ligature with Oba E or non-word-initial Una E by giving it a descender. These ligatures cannot have unakirain except for a single bar below which strikes through the descender similar to Cu with bar above.

- Be:

- Cannot have unakirain except for bar below, which is moved to above the horizontal stroke.

- Has a variant form when struck through.

- He cannot have obakirain.

- Re Haji:

- When writing languages with multiple rhotic phonemes, it can be used to represent one of them (usually a less common one, such as Wanya's [ʁ]). For other languages, it is only used in word-initial position.

- Cannot have obakirain or unakirain.

- Fe loses its descender when it has unakirain.

- Me cannot have obakirain or unakirain.

- A logographic Daag after a kotoba or foreign full-height glyph is written as the kotoba Day instead.

- De cannot have unakirain.

- Na cannot have unakirain.

- Re Mellan:

- When writing languages with multiple rhotic phonemes, it can be used to represent one of them (usually a more common one, such as Wanya's [r] or [ɹ]). For other languages, it is only used in word-medial and word-final positions.

- Cannot have obakirain or unakirain.

- Še has a word-initial variant where the leftmost stroke gains an ascender.

- The word-initial variant is not used when Še has any obakirain.

- Ze cannot have unakirain.

- No other obakirain or unakirain are allowed on a kirain with a combining g, except for a bar below to turn it into [k], striking through the loop if the combining g is in unakirain form.

If a diacritic would be attached to a letter that cannot have that diacritic (or to the start of a word):

- For a reduplication mark, instead repeat the kirain.

- For a bar below signifying [l], instead write a Le after the kirain.

- For other diacritics, instead write a Le after the kirain and attach the diacritic (and any others that follow) to it.

Kotoba

The canonical order of the kotoba is:

- Yes

- No

- What

- Understand

- First Person Singular

- Second Person Singular

- Third Person Singular

- First Person Plural

- Second Person Plural

- Third Person Plural

- Word

- Person/And

- Place

- Time

- Can

- Must

- May

- Question

- Go

- If

- Or

- And Or

- But

- This

- That

- Day

- Now

- Past

- Future

- Want

- Make

- Language

Some kotoba like What, This, or That can be combined with other kotoba to form compounds, regardless of whether the spoken word(s) they represent can be analyzed as the individual kotoba. For example, "ka plas" and "doko" are two ways to say “where” in Viossa, and both can be written as the kotoba What followed by the kotoba Place.

Numerals

There are two ways to write numbers in fantazkirain: using Western Arabic numerals or using Chinese numerals.

Ordinals are written with the suffix Es, derived from the Viossa suffix for ordinals (e.g. "kasi" “eight” → "kasis" “eighth”).

Dates are written as the year number followed by the kirain Te, followed by the month number followed by the kirain Me, followed by the day number followed by the kirain Daag. The use of these kirain is derived from the Viossa words for year ("toši"), month ("mwai"), and day ("daag"). In full dates, the Te and Me are written as forward slashes.

Other characters

There is also a name marker, used as a prefix for names and proper nouns. It is not read aloud. Rules:

- The name marker goes to the left of the name regardless of the writing direction of the writing system of the name.

- The name marker is not used for names consisting entirely of logograms.

- It is optional in front of a name that's a Viossa word.

- Compound words where the first part is a name may use a modified name marker that underlines the name part. Where this is not practical, the regular name marker may instead be combined with hyphenation.

Punctuation

Regardless of the language being written, fantazkirain mostly uses the same punctuation rules as English, including apostrophes to indicate contractions, such as the Viossa "f'un" (“my”). The main difference is that straight ASCII quotes ("") are used instead of typographic curly quotes (“”). fantazkirain uses logical quotation.

Unicode

The following proposal will be made to the UCSUR, leaving the decision of where to position the block to KreativeKorp. The following table uses a starting position of N as a placeholder.

| Fantazkirain | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+N+x | ||||||||||||||||

| U+N+1x | ||||||||||||||||

| U+N+2x | ||||||||||||||||

| U+N+3x | ||||||||||||||||

| U+N+4x | ||||||||||||||||

This chart uses a Ge Tolka as a visual placeholder for combining g. Its actual appearance varies depending on the preceding kirain (see #Diacritics).