Béu : Chapter 6

..... Copula's

The word copula comes from the Latin word "copulare" meaning "to tie", so a copula is a verb that ties. In béu(as in other languages) they differ from normal verbs in that they are quite irregular.

Also in béu a copula clause taiviza requires a specific word order and the s (the ergative case) is never suffixed to any noun, as normally happens when a verb is associated with two nouns.

... jìa

jìa is the béu main copula and is the copula of state. It is the equivalent of "to be" in English, which has such forms as "be", "is", "was", "were" and "are".

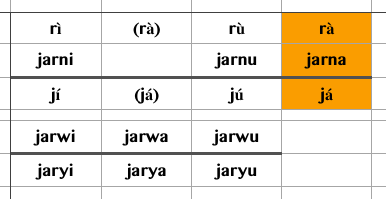

The table below echoes the second table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In three rows (the second and the two at the end) the copula includes the subject marker. In the table a representing first person singular is given. In rows 1 and 3 the copula does not include the subject marker (so obviously when these form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedent word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or já followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Actually rà is usually dropped completely.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... gí já moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... pá rà moltai = I am a doctor

Another situation where rà tends to be used is when either the subject or the copula complement are longish trains of words. For example ...

solboi alkyo ʔá dori rà sawoi = Those alcoholic drinks that she made are delicious.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

... làu

làu is the béu is the copula of change of state. It is the equivalent of "become" in English.

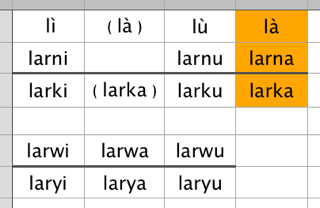

Again the table below echoes the table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In four rows (the second, third and the two at the end) the copula includes the cenʔo. In the table the a of the first person singular is given. In the first row the copula does not include the cenʔo (so obviously when this form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedant word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or ká followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

As you can see this copula is more regular than the main copula.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

làu haube = to become beautiful OR to become a beautiful woman

... The copula of existence

Some languages have a verb to indicate that something exists. twái

This usually introduces a new protagonist in a narrative. The new protagonist is by definition, indefinite. For example ...

twor glá gáu ʔaiho = There was an old and ugly woman

Often it is used with a phrase of location.

nambopi twuru aiba glabua = There will be three people in the house .... 3 people are in the house ???

There is no word that corresponds to "have". The usual way to say "I have a coat" ...

pán twor kaunu = "at me exists a coat"

olwa = to exist

elya = to not exist

??????????????????

há = place

dí = this

dè = that

While you sometimes come across the há dí the word hái is the usual way to express "here".

In a similar manner you sometimes come across the há dè the word ade* is the usual way to express "there".

*This word is an exception to the rule that inside a word and between vowels, d can be either pronounced as "d" or "ð". In ade the d is always pronounced "ð".

There is a house = A house exists = ade (rà) nambo

This is patterned on the more general locative construction.

In the apple tree is a beehive ????

ade pona paye = "I feel cold" ... maybe against expectations ... no reason to think that other people would be cold.

ʃi pona = "It is cold" ... everybody should feel cold

..

..... To the "n"th degree

Nouns

The following 2 word are "specifiers" and come before a noun. The noun is always in the singular. The noun can be a countable or a non-countable noun.

uʒya báu = many men

igwa báu = a few men

uʒya moze = a lot of water

igwa moze = a little water

As compared to some idea that is in the background as to what a typical amount of "men" would be.

uzge báu = more men

ige báu = less men

As compared to some recently mentioned amount of "men".

ume báu = the most men

ime báu = the least men

Adjectives

gèu lùn = very green

gèu lín = a little green

gèu lùa = more green

gèu lía = less green

gèu lùas = most green

gèu lías = least green

Verbs

solbe lùn = to drink a lot

solbe lín = to drink a little

solbe lùa = to drink more

solbe lía = to drink less

solbe lùas = to drink most

solbe lías = to drink least

Adverbs

gadewe lùn = very slowly

gadewe lùa = more slowly

gadewe lùas = the most slowly

..... The sides of an object

sky nambon = above the house

awe (rá) nà sky nambon = the bird is above the house .... sometimes nà can be left out as well ... awe sky nambon = the bird is above the house (a phrase) the NP (the bird above the house) ....

earth nambon = under the house

face nambon = front of the house

arse nambon = behind the house

kà = side

aibaka = a triangle

ugaka = a square

idaka = a pentagon

elaka = a hexagon

ò atas nambo = he/she is above the house ... however if "house" is understood, and mention of it is dropped, we must add ka to atas ... for example ...

ò ataska = he/she is above

daunika = underneath

liʒika = on the left hand side

luguka = on the right hand side

noldo, suldo, westa, istu niaka, muaka faceside backside etc. etc.

..... The verb complex or verb phrase

Also often called the predicate. Called the jaudauza in béu

The predicate is made up of ...

1) one of two particles that show likelihood which are optional.

In the béu linguistic tradition they are called mazebai. The mazebai are a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles)

2) one of five particles that show modality. These are also optional.

In the béu linguistic tradition they are called seŋgebai. The seŋgebai are a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles)

3) a gomua (a full verb)

... mazebai

These appear first in the predicate.

These particles show the probability of the verb occurring.

1) màs solbori = maybe he drank

2) lói solbori = probably he drank

You could say that the first one indicates about 50% certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty

... seŋgebai

These appear next in the predicate.

These particles correspond to what is called the "modal" words in English. The five seŋgeba are ...

1) sú which codes for strong obligation or duty. It is equivalent to "should" in English. In English certain instances of the word "must" also carries this meaning.

2) seŋga which codes for weak obligation. It is equivalent to "ought to" in English. (Note ... in certain dialects of English "ought to" is dying out, and "should" is coding weak obligation also)

3) alfa which codes for ability. It is equivalent to "can" in English. As in English it means that subject has the strength or the skill to perform the action. Also as in English it codes for possibilities/situations which are not dependent on the subject. For example ... udua alfa solbur => "the camels can drink" in the context of "the caravan finally reached Farafra Oasis"

4) hempi which codes for permission. It is equivalent to "may" or "to be allowed to" in English. (Note ... in certain dialects of English "may" is dying out, and "can" is coding for permission also)

5) hentai means knowledge. It is equivalent to "know how to" in English. (Note ... in English certain instances of the word "can" also carries this meaning)

The form that these seŋgeba and the main verb take appears strange. Where as, logically, you would expect the suffixes for person, number, tense, aspect and evidential to be attached to the seŋgeba and the main verb maybe in its infinitive form, the seŋgeba do not change their form and the suffixes appear on the main verb as normal. This is one oddity that marks the seŋgeba off as a separate word class.*

Some examples ...

1)

a) sú -er => you should visit your brother

b) sú -eri => you should have visited your brother

c) sú hamperka animals => you should not feed the animals

d) sú hamperki animals => you shouldn't have fed the animals

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza súa

2)

a) seŋga humper little => you ought to eat a little

b) seŋga humperi little => you ought to have eaten a little

c) seŋga solberka brandy => you ought to not drink brandy

d) seŋga solberki brandy => you ought to have not drunk that brandy

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza seŋgua

3)

a) fuà -or => he can swim across the river

b) fuà-ori => he could swim across the river

c) fuà solborka => he can stop drinking

d) fuà solborki => he could stop drinking

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza fùa

4)

a) hempi bor festa => "she may go to the party" or "she can go to the party" or "she is allowed to go to the party"

b) hempi bori festa => she was allowed to go to the party

c) hempi borka school => he is allowed to stop attending school

d) hempi bori school => he was allowed to stop attending school

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza hempua

5)

a) hentai bamor car => "she can drive a car" or "she knows how to drive a car"

b) hentai bamori car => she knew how to drive a car

c) hentai boikorka car => He has the ability not to crash the car

d) hentai boikorki car => He had the ability not to crash the car

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza hentua

*Two other oddities also marks off the seŋgeba as a separate word class. These are ...

1) When you want to question a jaudauza containing a seŋgeba you change the position of the main verb and the seŋgeba. For example ...

bor hempi festa => "may she go to the party" ... shades of English here.

2) All 5 seŋgeba can be negativized by deleting the final vowel and adding aiya. For example ...

faiya -or ??? => he can't swim across the river

Note ... sometimes the negative marker on the seŋgeba can occur along with the normal negative marker on the main verb to give an emphatic positive. Sometimes it produces a quirky effect. For example ...

jenes faiya humpor cokolate => Jane can't eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability to eat chocolates) ... for example she is a diabetic and can not eat anything sweet.

jenes fa humporka cokolate => Jane can not eat chocolates (Jane have the ability not to eat chocolates)... meaning she has the willpower to resist them.

jenes faiya humporka cokolate => Jane can not not eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability, not to eat chocolates) ... meaning she can't resist them.

There are 5 nouns that correspond to the 5 seŋgeba

anzu = duty

seŋgo = obligation

alfa = ability

hempo = permission or leave

hento = knowledge

Note on English usuage (in fact all the Germanic languages) ... the way English handles negating modal words is a confusing. Consider "She can not talk". Since the modal is negated by putting "not" after it and the main verb is negated by putting "not" in front of it, this could either mean ...

a) She doesn't have the ability to talk

or

b) She has the ability to not talk

Note only when the meaning is a) can the proposition be contracted to "she can't talk". In fact, when the meaning is b), usually extra emphasis would be put on the "not". a) is the usual interpretation of "She can not talk" and if you wanted to express b) you would rephrase it to "She can keep silent". This rephrasing is quite often necessary in English when you have a modal and a negative main verb to express.

... wepua

We have already mentioned the two mazeba at the beginning of this section.

Actually there is another particle that occurs in the same slot as the mazeba and it also codes for likelihood. This is wepua and it constitutes a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles) all by itself.

1) más solbori = maybe he drank

2) lói solbori = probably he drank

3) wepua solbori = he must have drank

You could say that while the first one indicates about 50% certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty, the third shows 100% certainty.

3) Indicates that some "evidence" or "background information" exists to allow the speaker to assert what he is saying. It also carries the meaning "there is no other conclusion given the evidence".This obviously has some functional similarities to the -s evidential. However the -s evidential carries less than 100 % certainty ...

solboris = I guess/suppose he drunk

wepua never appears in front of the first two seŋgebai. This is the difference between wepua and the mazebai.

The word wepua is derived from pè meaning "to need". pòi means necessities.wepua can be thought of as meaning something like "being necessary" or "of necessity".

.... -fa, and -inda

These all form adjectives. The first might have some connection with a seŋgeba.

i.e. solbe = to drink

moze = water

moze solbefa = drinkable water

Maybe related to fua "can".

moze solbinda = water worth drinking

There is also another suffix, but this one can be said to be unrelated to "like" kinda

Maybe related to kinda "to like".

.... Case frames

I was originally going to give the word klói "to see" the following case frames {k, ∅} {s, ∅} {∅}

In the first the A argument would be marked by the non-canonical -k affix and would mean "see"

In the second the A argument would be marked by the canonical -s affix and would mean "look at" or "observe".

In the third, it would mean "be visible"

However we would have ...

pàk nambo klori = I saw the house

pás nambo klori = I looked at the house

However the above 2 would be the dame if the pronoun would be dropped, so I decided against the {k, ∅} case frame and klói having the meaning "look at"

Also the {∅} case frame was dropped as ...

klori nambo could mean "the house is visible" but also "he saw the house" (I like the idea of dropping 3rd person A pronouns as well as 1st and 2 nd person A pronouns)

Actually is it possible to drop 3rd person A pronouns ??

So we are left with the case frame {s, ∅}. As with all words with the single case frame {s, ∅} it is possible to drop the either of the 2 arguments when they are known by background. If only one is given, which one it is is of course known (i.e. does it end in an s or not) ... so there should be no confusion ???

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences