Béu : Chapter 2

..... How A O and S arguments are identified

In this section we discuss pronouns and also introduce the S, A and O arguments.

béu is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings.

..

In English there is a fixed word order, which also helps to tell who did what to who when the participants are given as nouns instead of pronouns. In béu the order of the verb and the participants are not fixed as in English.

..

glàs baú timpori = The woman hit the man

glà baús timpori = The man hit the woman

It can be seen that "s" is added to the "doer" of the action.

..

However consider the clause below ...

..

glà doikor = The woman walks

It can be seen that the "doer" does not have an attached "s" in this case.

The reason is that "to walk" is an intransitive verb while "to hit" is a transitive verb

It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument.

It is the convention to call the "doer" in a transitive clause the A argument and the "done to" the O argument.

A language that has the S and O arguments marked in the same way is called an ergative language

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument).

In béu ò is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : ós is the "doer to"(A argument).

..

..... Transitivity and the very useful word "é"

..

In béu a verb is either transitive or intransitive. There is no "ambitransitive verbs as in English.

For example ... in English, you can say ... "I will drink water" or simply "I will drink"

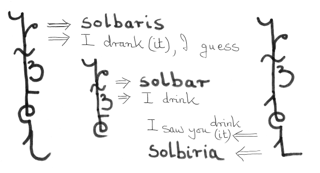

The second option is not allowed in béu ... as "drink" is a transitive verb, you must say "I will drink something" = solbaru é

For another example ... in English, you can say ... "the woman closed the door" or simple "the door closed".

The second option is not allowed in béu ... as "close" is a transitive verb, you must say "something closed the door" = pintu nagori és

(Actually there is another option for expressing the above ... you can change any transitive verb to an intransitive verb ... pintu nagwori = "the door was closed"

..

If an argument is definite in béu it is usually comes before the verb, and if indefinite it usually comes after the verb.

Now the word é is by definition indefinite. It actually means "somebody" OR "something". What happens if this word is put before the verb.

Well something quite interesting happens ... é changes into a question word meaning "who" or "what"

For example ... és pintu nagori = Who/what closed the door

For another example ... "what will I drink" = é solbaru

And yet another one ... "who drank the water" = és moze solbori

..

..... Pronouns

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the A argument.

..

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

Because the person and number of the A or S argument is expressed in the actual verb. The above are usually dropped (however the third person pronoun is occasionally retained to give the distinction between human and non-human subject) so when the pronouns above are come across, it might be better to translate them as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the S or O argument. When they are used as an S arguments (i.e. with an intransitive verb), it might be better to translate these pronouns as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

The above table is for S and O arguments, it fact we have another pronoun but this one only occurs as an O argument. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves we use tí to represent the O argument.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in béu we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari.

It is a rule that tí must follow the A argument (if it is overtly expressed ... i.e. by a free-standing pronoun and not just in the verb)

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

..

The possessive form of these pronouns are ...

..

| my | pàn | our | yùan |

| our | wìan | ||

| your | gìn | your (plural) | jèn |

| his, her | òn | their | nùn |

| its | ʃìn | their | ʃìn |

..

And we also have tín which is used if the possessor is the same as the subject of the clause.

Actually the n suffix is the locative. In the grammar, location and possession are marked identically.

..

..... Building up a noun phrase (NP)

..

Now we talk about the béu noun phrase (cwidauza'). This can be described as ;-

Quantifier1 Head2 (Adjective3 x n) Genitive4 Determiner5 Relative-clause6

1) The Quantifier/Specifier is either a number or a word such as "all", "many", "a few" etc.

2) The head is usually a noun but can also be an adjective. When you come across an adjective as head of a noun phrase, its meaning is "the person/thing that is "adjective" ".

3) An adjective ... not much to say about this one, you can have as many as you like, the same as English.

4) A noun or pronoun that qualifies another noun (commonly called the Genitive in the Western linguistic tradition). Formed by suffixing -n to a normal noun makes it into a genitive.

5) Either dí "this", or dè "that".

6) This is a clause, beginning with ʔà that qualifies the head of the noun phrase. ʔà can be considered as a nominalizer, that is it is a particle that changes the following clause into a noun.

An interesting point is that in the absence of a "head", any of the other elements can act as the head.

..

..... The R-form of the verb

So far we haven't said much about the verb as such, although we have come across the infinitive (gomia).

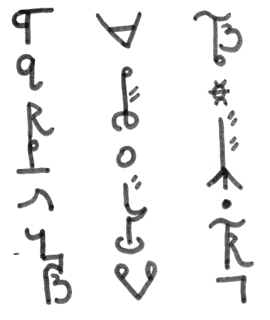

We will discuss the most-used form of the verb in this section, the R-form. But first we should introduce a new letter.

Above it is shown appearing in some active verbs. Just remember to put an extra little florish on the "r" when it occurs word finally, just to distinguish it from word final "j".

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the R-form of the verb.

So if you hear "r" or see the above symbol, you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause. (definition of a clause (semo) = that which has one "r" ... ??? )

O.K. ... the R-form is built up from the gomia*.

1) the final vowel is deleted from the gomia.

*Excepts in rare cases (see "Adjectives and how they pervade other parts of speech")

... Slot 1

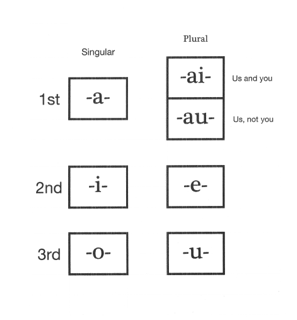

2) one of the 7 vowels below is added.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the Western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she). In the béu linguistic tradition they are called cenʔo-markers. (cenʔo = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play)

These markers represent the subject (the person that is performing the action). Whenever possible the pronoun that represents the subject is dropped, it is not needed because we have that information inside the verb with the cenʔo-markers.

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one must be used when the people performing the action included the speaker, the spoken to and possibly others. The lower one must be used when the people performing the action include the speaker, NOT the person spoken to and one or more 3rd persons.

Note that the ai form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

... Slot 2

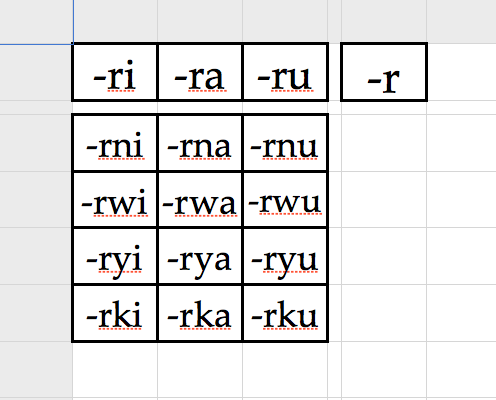

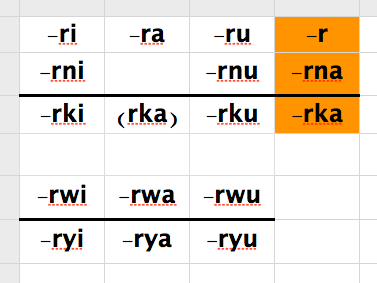

3) now one of the 16 markers shown below is added. 16 is quite a respectable number, as far as tense/aspect markers go.*

Now these markers represent what are called tense/aspect markers in the Western linguistic tradition. In the béu linguistic tradition, they are called gwomai or "modifications". (gwoma = to alter, to modify, to adjust, to change one attribute of something).

The table above has the gwoma arranged according to form. The two arrays below have the gwoma arranged according to meaning. The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have one entry enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a negative present tense negative you would express it periphrastically ... you would use the tenseless negative -rka followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Looking at the upper table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... i for the past, a for the present and u for the future.

-ri ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

-ra ... Should only be used if the action is happening NOW. English uses "to be xxxing". For example doikara = I am walking ... (doika = to walk)

-ru ... This is the future tense.

-r ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly".

The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school), Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). Actually in béu the pattern is broken a bit, in that -rna has NOTHING to do with the activity going on at the time of speech, it is actually a tenseless habitual. Also béu and English behave the same in the following way ... whereas by logic we should use doikarna in "I walk (to school everyday)", in fact doikar is used. doikarna would be used only if we were going on to MENTION some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift)

doikarna = "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use doikar

-rnu ... Now English doesn't have a future habitual. But if it did it would have a roll. For instance, suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In béu you would answer doikarnu.

The next row expresses the perfect tense.

While the perfect tense, logically this doesn't have that much difference from the past tense it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John. And think about the difference in meaning between "she has fallen in love" and "she fell in love" ... the first one means "she is in love" while the second one just talks about some of her history.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

Easy to translate into English ... doikorwi = He/she had walked ... doikorwa = He/she has walked ... doikorwu = He/she will have walked

The next row expresses the "not yet" tense.

Easy to translate into English ... doikoryi = He/she had not yet walked ... doikorya = He/she hasn't walked yet ... doikoryu = He/she will not have walked

Notice that the English translation, doikoryu is just the negative of doikorwu. Interesting eh ? In fact these two aspects can be in many ways regarded as the negatives of each other, although in English only the future tense gives the surface forms this way.

Which leads us on to the next row. This row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2 (that is right, row 2 does not have its own negative).

Just as -rna does not specify the present tense but instead gives a tenseless habitual, -rka gives a tenseless negative.

Easy to translate into English ... doikorki = He/she didn't walk ... doikorka = He/she doesn't walk ... doikorku = He/she will not walk

You may have noticed that the béu letter that negates verbs is very similar to the Chinese character that negates verbs (bù). This is pure coincidence.

By the way, the béu terms for the five aspects represented by these 5 rows are ... baga, dewe, pomo, fene, and liʒi.

*But even with 16 tense/aspect markers, not EVERY situation can be exactly expressed.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out" (using the progressive plus the perfect aspects). The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" (or working out over some period of time) to build up muscles. béu has no tense/aspect marker so appropriate.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

By the way, in the above example, the muscular schoolmate would use the r form of the verb plus the béu equivalent of "now", to explain his present condition. Good enough.

... Slot 3

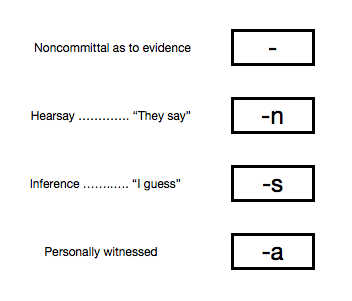

4) and finally one of the 4 teŋko-markers shown below is added.

teŋkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate" ... teŋko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. As evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In béu there are 4 evidential suffixes. One is what is called a zero suffix. And in meaning it gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based.

a) doikori = He/she walked ... this is neutral. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is saying what he is saying.

b) doikorin = They say he/she walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

c) doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow.

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The fourth tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

d) doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself".

This last teŋko can only be used with one of the gwomai . It can ONLY be used with the plain passed tense form i.

An o is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s".

..... The case system

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON are called "cases". The classical languages, Greek and Latin had 5 or 6 of these. Modern-day Finnish has about 15 (it depends on how you count them, 1 or 2 are slowly fading away). Present day English still has a relic of a once more extensive case system : most pronouns have two forms. For example ;- the third-person:singular:male pronoun is "he" if it represents "the doer", but "him" if it represents "the done to".

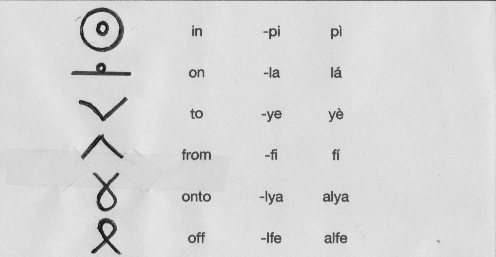

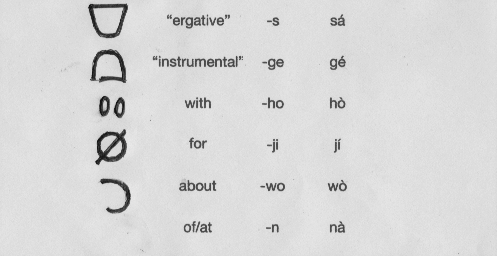

The 12 béu case markers are called pilana

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana <= (pila + ana), in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle". It is an adjective which means "putting (something) in position".

As béu adjectives freely convert to nouns*, it also means "that which puts (something) in position" or "the positioner".

Actually only a few of them live up to this name ... nevertheless the whole set of 12 are called pilana in the béu linguistic tradition.

..

The pilana are suffixed to nouns and specify the roll these nouns play within a clause or within a NP.

The pilana are abbreviated to a single consonant in the béu writing system. That is, in the béu writing system, the final vowel of all pilana.

The pilana are partly an aid to quicker writing. However they also demarcate a set of 12 affixes and make quite a neat system.

You could call these 12 plus the unmarked noun a case system of 13 cases. Well you could if you wanted to (up to you).

Note that -lya and -lfe are represented by a special amalgamated symbols which do not occur elsewhere.

Notice that by a addition of pilana, you might expect to get the forms alye and alfi. As you can see this is not the case. Perhaps the amalgamated form has the final vowel changed under the pull of the initial vowel, a.

* You can tell if pilana is being an adjective or a noun by the environment that you find it in.

Now one quirk of béu (something that I haven't heard of happening in any natural language), is that the pilana is sometimes realised as an affix to the head of the NP, but sometimes as a preposition in front of the entire NP. This behaviour can be accounted for with thing with two rules.

1) The pilana attaches to the head and only to the head of the NP.

2) The NP is not allowed to be broken up by a pilana. The whole thing must be contiguous. So if a NP has elements after the head the case must be realised as a preposition and be placed in front of the entire noun phrase.

So if we have a NP with elements to the right of the head, then the pilana must become a preposition. The prepositional forms of the pilana are given on the above chart to the right. These free-standing particles are also written just using the symbols given on the above chart to the left. That is in writing they are shorn of their vowels as their affixed counter-parts are.

The letters m, b, k, g and d are free to be used as abbreviations. Perhaps m <= mò, two particles for joining clauses etc. etc.

*Another case when the pilana must be expressed as a prepositions is when the noun ends in a constant. This happens very, very rarely but it is possible. For example toilwan is an adjective meaning "bookish". And in béu as adjectives can also act as nouns in certain positions, toilwan would also be a noun meaning "the bookworm". Another example is ʔokos which means "vowel".

-pi or pì

meu (rà) "basket"pi

While the original meaning was about space, this pilana is very often found referring to time.

I read the book hourpi => I read the book in an hour

I gets dark pi ten minutes => It get dark in ten minutes

She qualified as a doctor pi five years

One can get from Glasgow to London daypi

I'm coming to Sweden pi next month

meu (rà) topla basketn = The cat is on top of the house

meu (rà) interior basketn = the cat is in the basket

-la or lá

mat (rà) floorla => the mat is on the floor ... notice "the mat"

twor mat floorla => there is a mat on the floor ... notice "a mat". Also the verb two is usually sentence initial, at least when introducing something new.

meu (rà) topla nambon => The cat is on top of the house

Notice that "topla nambon" is allowed, I should mention this somewhere.

twor ble pàn = I have (some) money

ble twor pàn = I have the money

tworka ble pàn = I don't have any money .... Note that it is also possible to say twor yà ble pàn, but the first method is definitely preferred.

ble tworka pàn = I don't have the money

bird (rà) top nambon = The bird is above the house

Notice that in the above example "top" is considered a specifier ... "top nambo" forms a tight compound.

The eight specifiers of location are above, below, right, left, this side (with respect to the speaker, of course), the far side

yè and fí are not used for locations. Instead the transitive verbs "arrive" and "leave" are used in a SVC.

Also the words "come" and "go" covered by "arrive" and "leave".

When not talking about location, yè and fí are used.

For example ...

She gave food to the beggar = ...... beggarye

The beggar got food from the woman = ...... wamanfi

Verbs such as hear and tell use these pilana also.

Also such sentences as ...

I was made to sing by the guard = I receive sing guardfi

He made the prisoner sing = He give sing prisonerye

Also such sentences as ...

He went from being very rich, to very poor, within six months

use yè and fí

-ye or yè

kyiwa toili oye = give the book to her

This is the pilana used for marking the receiver of a gift, or the receiver of some knowledge.

However the basic usage of the word is directional.

*namboye = "to the house"

distanceye nambon = "as far as the house"

"limit"ye nambon = "up to the house" ... this usage is not for approaching humans however ... for that you must use "face".i.e. "face"ye báun = right up to the man

yèu = to arrive ... yài a SVC meaning "to start" ... fái a SVC meaning "to stop" ???

-fi or fí

nambofi = "from the house"

fí "direction" nà nambo = "away from the house" i.e.you don't know if this is his origin but he is coming from the direction that the house is in.

fí "limit/border" nà nambo = all the way from the house

fí "top" nà nambo = from the top of the house ... and so on for "bottom", "front", etc. etc.

he changed frog.fi ye prince handsome = he changed from a frog to a handsome prince

fía = to leave, to depart ... fái a SVC meaning "to finish" .... then bai cound mean continue and -ana would be the present tense ???

-lya or alya

Sometimes called the "Allative case". Can be said to translate to English as "onto".

The x means that the previous vowel is repeated.

xxx yyy zzz = put the cushions on the sofa

-lfe or alfe

The ablative

-s or sá

that Stefen turned up drunk at the interview sank his chance of getting that job

sá tá ........

-ge or gé

The instrumental is used for nouns that represent the instrument ("with"), the means ("by") or the agent ("by").

John writes with a pen

banu = to learn

banuge = by learning

book was written page = The book was written by me

andage = manually

I work as a translator ??? ... I work sàu translator ??

gé ta ...

-ho or hò

The commitive

"in the company of", often used with the personal pronouns ;-

| with me | paho | with us | yuaho |

| with us | wiaho | ||

| with you | giho | with you (plural) | jeho |

| with him, with her | oho | with them | uho |

| with it | ʃiho | with them | ʃiho |

tùa = to use, to wear ... tàu a SVC meaning ??

-ji or jí

The benefactive. Sometimes used with gomia

banu = to learn, banuji = in order to learn

-wo or wó

Not used for the locative sense of about, it has the sense "with respect to" more. Used for example when have the word halfa = to laugh.

1) pà halfari = I laught

2) pà halfari jonowo = I laught at John

Is 2) a transitive verb ? Semantically transitive maybe ... but (in English and in béu), John is introduced by a preposition ... so I guess 2) is not transitive ???

2) pà halfari jonoye = I taunted John

Used for marking the "theme" as in such sentences as the one below.

gala caturi jonowo => The women were talking about John

jonowo ... = as for John ....

-n or nà

The locative or the possessive. Basically if the noun is human, it is the possessive : if the noun is non-human, it is locative.

nambo jonon (rà) hauʔe = John's house is beautiful

jono (rà) nambon = John is at home

Some example;-

fanfa = horse

sonda = son

blico = king

fanfa sondan = the horse of the son

sonda blicon = the son of the king

However the suffixed form can only be used if the genitive is a single word. Otherwise the particle na must be placed in front of the words that qualify. For example ;-

We can't say *fanfa sondan blicon however. The -n on sonda is splitting the NP sonda blico.

So we must say fanfa nà sonda blicon

Some more examples ...

fanfa nà sonda jini blicon = "the horse of the king's clever son

fanfa nà sonda nà blico somua = "the horse of the fat king's son"

..... The gomiaza

gomiaza could be translated as "infinitive phrase"

gomia have some similarities to nouns. However they differ in that they never take plurals, are never "possessed" and although they take 8 of the 12 pilana, some of the rolls that these pilana play differ quite a bit from the rolls they play with nouns.

Also when a pilana is joined to a gomia, if it ends in a diphthong, then the final vowel is dropped. For example ...

kludau = to write

kludala = writing (adjective)

Note ... the final vowel is not dropped when the gomia is a monosyllable.

REDO ALL THE STUFF BELOW ... also tie in the participle phrase (equivalent to Dixon's complement clause)

Near the start of this chapter we saw how béu builds up a NP (noun phrase). Now gomia is a noun so gomia can be the head of the structure given above.

If a gomia is put in the structure above then the word put in the "genitive"* slot corresponds to the O argument if the action was described using an active verb.

It must be restated that ONLY the O argument can go in the "genitive" slot. English is quite permissive when it comes to sticking on arguments to verbal nouns. Witness ...

1) Attila's destruction of Rome

2) Rome's destruction (by Attila)

In béu if the A argument is to be represented in the gomia NP, it is introduced by the instrumental.

In actual fact gomia NPs can be quite long with all sorts of place, time and manner arguments tagged on to the end.

However there is a second way to build up a gomia NP. This type of NP has "A gomia O "other peripheral arguments". For example ????

There can be no mixing of these 2 types of gomia NP.

*And when it comes to word building. The O argument can be subsumed into the verb. .... hunting of ducks => duckhunting

And possibly as a back formation from the above, "duck-hunt" can be used as an active verb.

..... 64 Adjectives

| good | bòi* | bad | kéu |

| long | làu | short | lái |

| high, tall | hài | low, short | ʔáu |

| right, positive | lugu | left, negative | liʒi |

| white | ái | black | àu |

| young | sài | old (of a living thing) | gáu |

| clever, smart | jini | stupid, thick | tumu |

| near | nìa | far | múa |

| new | yaipe | old, former, previous | waufo |

| big | jutu | small | tiji |

| hot | fema | cold | pona |

| open | nava | close | mapa |

| simple, easy | baga | complex, difficult, hard | kaza |

| sharp | naike | blunt | maubo |

| wet | nuco | dry | mide |

| empty | fene | full | pomo |

| fast | saco | slow | gade |

| strong | yubu | weak | wiki |

| heavy | wobua | light | yekia |

| beautiful | hauʔe | ugly | ʔaiho |

| contiguous, touching | yotia | apart, separate | wejua |

| fat | somua | thin, skinny | genia |

| bright | selia | dull, dim | golua |

| thin | pilia | thick | fulua |

| east, dawn, sunrise | cúa | west, dusk, sundown | dìa |

| tight | taitu | slack, loose | jauji |

| neat | ilia | untidy | ulua |

| soft | fuje | hard | pito |

| wide/broad | juga | narrow | tisa |

| rough | gaʔu | smooth | sahi |

| deep | gubu | shallow | siki |

| right | sèu | wrong | gói |

In the above list, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning. However in béu there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | au | |||

| f | o | |||

| b | oi | |||

| g | i | |||

| d | ia | high tone | ||

| l | =========================== | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ua | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | u | |||

| k | eu | |||

| p | e | |||

| t | ai | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

* Note that the adverb version of this word is slightly irregular. Instead of boiwe it is bowe. People often shout this when impressed with some athletic feat or sentiment voiced ... bowe bowe => well done => bravo bravo

Also instead of keuwe we have kewe. People often shout kewe kewe kewe if they are unimpressed with some athletic feat or disagree with a sentiment expressed. Equivalent to "Booo boo".

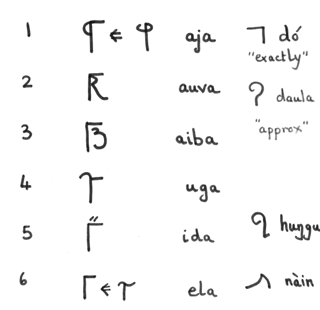

..... Simple arithmetic

noiga = arithmetic

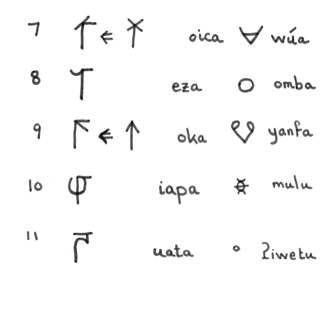

Above right you can see the numbers 1 -> 11 displayed. Notice that the forms of 1, 3, 6, 7 and 9 have been modified slightly before the "number bar" has been added.

In the bottom right you can see 7 interesting symbols. These are used to extend the range of the béu number system (remember the basic system only covers 1-> 1727). Their meanings are given in the table below.

| elephant | huŋgu |

| rhino | nàin |

| water buffalo | wúa |

| circle | omba |

| hare | yanfa |

| beetle | mulu |

| bacterium, bug | ʔiwetu |

To give you an idea of how they are used, I have given you a very big number below.

Which is => 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... E represents eleven and T represents ten ... remember the number is in base 12.

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only: if you can handle this number you can handle any number.

This monster would be pronounced aja huŋgu ufaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaifau dó

Now the 7 "placeholders" are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. Used in the same way that we would say "point"/"decimal" when reeling off a number.

When first introduced to this system, many people think that the béu culture must be untenable, however strangely enough the béu culture has lasted many thousands of year, despite the obvious confusion that must arise when they attempt to count elephants.

One further point of note ...

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say aufaidaula nàin .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say yanfa elaibau .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630" instead of "630 micro".

To make a number negative the "number bar" is placed on the left. See below ;-

Also a number can be made imaginary by adding a further stroke that touches the "number bar". See below ;-

As you can see above, there is no special sign for the "addition operation". The numbers are simply written one beneath the other. Similarly with subtraction but one number would be negative this time.

There is a special sign to indicate multiplication (+), and there is an equals sign (-).

Division is the same as multiplication except that one of the numbers is in "fractional form".

There is an alternative multiplication/division notation : instead of using the + sign, the two quantities can instead be written side by side (see the example above).

-6 is pronounced ela liʒi ... liʒi means left or "negative

By the way lugu means right (as in right-hand-side) or positive.

4i is pronounced uga haspia ... and what does haspia mean, well it is the name of the little squiggle that touches the number bar, for one thing.

-4i is pronounced uga haspia liʒi

-1/10 is pronounced diapa liʒi

i/4 is pronounced duga haspia

And so ends chapter 2 ...

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences