Béu : Chapter 3

..... When a noun qualifies another one

A) When the relationship between the nouns is one of ownership (usually a thing owned by a person), the thing comes first and it is followed by the person, with the person taking the pilana of location.

B) When the relationship between the nouns is "part to the whole", with the noun denoting the whole taking the pilana of location.

C) When the relationship between the nouns is a kinship relationship the attribute noun takes the pilana of location.

D) When the relationship between the nouns is of an attribute ( see page 265 ) the attribute noun takes the pilana of location.

F) When the relationship between the nouns is association, the attribute noun takes the pilana of location.

E) "above the house" = atas nambo ... for the same reason, people get their knickers in a twist about this one. However these "locative words" are a bit different as they are hardly ever used alone (maybe in the past they were, that is if béu had a past). If they are uttered without in isolation these days the invariably have ka suffixed.

M) "cup of water" = cup moze ... people get their knickers in a twist about this one. "cup" must be the head, but surely water is more important. That is, semantically "water" is the "head" but syntactically "cup" is the head. Well in the béu linguistic tradition we get around this by ???

Z) There is one more case to talk about. If something is made out something, then we use the preposition mò meaning "out of". For example ....

a cup of gold ???

Think about other situations in which we can use this partative case (look at Finnish).

..... How to bring a word into focus

Actually there is a way to focused elements in a statement which mirrors the way to focus elements in a question. We use cà for this.

Statement 1) báus glaye timpi alhai = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement 2) báus glaye cà timpi alhai = It is the woman to whom the man gave the flowers.

Any argument or in fact the verb itself can be focused in this way.

..... Questions

béu has a "toolbox" that allows us to ask questions. The tools in that box are ʔái, nái, gwaili and cái ... the 4 words used for asking questions.

..... How to ask a yes/no question

To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a YES/NO answer), we stick the particle ʔái on the end of the sentence.

ʔái is neutral as to the response you are expecting. If you are expecting a positive reply, you would use the particle ʔaiwa instead.

To answer a positive question, YES or NO ( ʔaiwa àu aiya ) is sufficient.

To answer a negative question positively, YES ( ʔaiwa ) is enough.

To answer a negative question negatively, you must give an entire clause.

For example ;-

Question 1) glà (rà) hauʔe ʔái = Is the woman beautiful ? .......... If she is beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she isn't answer aiya.

Question 2) glà ká hauʔe ʔái = Isn't the woman beautiful ? ........ If she isn't beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she is answer ò rà hauʔe. (notice that the copula must be used in this case)

Also it is possible to focus on a particular element when asking a YES/NO question in béu. This is done by putting the particle cái after the element that you want to focus on. For example ...

Statement 1) báus glaye timpi alhai = the man gave flowers to the woman

Straight question 2) báus glaye timpi alha ʔái = did the man gave flowers to the woman ?

Focused question 3) báus glaye cái timpi alha = Is it the woman that the man gave flowers to ?

Focused question 4) báus cái glaye timpi alha = Is it the man that gave flowers to the woman ?

Focused question 5) báus glaye timpi alha cái = Is it flowers that the man gave to the woman ?

Focused question 6) báus glaye timpi cái alha = the man GAVE flowers to the woman ?

..... How to ask a content question

béu is unusual in that it has only two content question words ... nái and gwaili.

English is more typical of languages in general and has 7 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

nái means "which" and most English content question words are equivalent to a generic noun followed by nái.

| what | dài nái |

| who | bù nái |

| where | hà nái |

| when | kyù nái |

| what type of .... | myàn nái |

| how | wè nái |

| why | lì nái |

| how much | bà nái |

| how many | nò nái |

To answer lì nái you would use gwài.... "because" or jí .... "in order to" / "to".

In English as in about 1/3 of the languages of the world it is necessary to front the content question word. This is not necessary in béu.

The pilana are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.

In fact there is one contraction that takes place. It is sá bù nái => sù nái.

So you could say that sù nái = "who", and bù nái = "whom"

Here are some examples of content questions ...

Statement 1) báus glaye kyori alhai = the man gave flowers to the woman

Question 2) sù nái glaye kyori alhai = who gave flowers to the woman

Question 3) báus ye bù nái kyori alhai = to whom did the man gave flowers

Question 4) báus glaye kyori dài nái = what did the man give to the woman

TO THINK ABOUT

Notice that in 5, nái and the word that it is conjoined with, can not be seperated by the pilana ye.

"which one" would be translated as ʃì nái if we are referring to a non-A argument and non-human.

"which ones" would be translated as nò ʃì nái if we are referring to a non-A argument and non-human.

"which one" would be translated as ò nái if we are referring to a non-A argument but human.

"which ones" would be translated as ù nái if we are referring to a non-A argument but human.

Of course to refer to an A argument, we simple add -s to the pronoun.

..... How to ask what is being done

béu is unusual in that it has a word that is a question verb.

ʔail- meaning "to do what". For example ...

ʔailiri = "what will you do"

ʔailora jonos jene = "what is John doing to Jane"

It doesn't have to be fronted but it usually is.

Some of the words mentioned above are very common. Because of this, they have a shorthand way of being written.

..... The 5 "specifiers"

You can say that béu is basically a SVO language (although actually any of the 6 orders possible are acceptable).

You can say that in the typical sentence, S is definite and O is indefinite or generic.

When O is definite, usually we switch to the SOV word order.

But what do we do when S is indefinite ?

Well in these cases we put a specifier in front of S. There are 5 specifiers ...

Specifying a thing from all things of that type

The 5 specifyana

| any | ʔín |

| some | án |

| some | àn |

| all | hùn |

| every single | hunin |

These words appear immediately before nouns. No nouns in plural form are allowed to appear after these "specifiers".

These 5 words have a special "shorthand" form. They are never written out in full. The shorthand form is given below.

ʔín toili = any book

án toili = some book

àn toili = some books

hùn toili = all books

hunin toili = each book, every book ... in the following discussion I consider "each" and "every" to mean exactly the same.

In English, in most instances, "all" and "each" mean the same thing. Both these word indicate "totality" but the second one also indicates "individuality". Because the second one indicates "individuality" the first one came to be associated with "togetherness".

But as I said. in English in most situations, "each"* and "all" are in free variation. "each" is the word that is used by default.

In béu, hùn is the word used by default. Only when "separateness/individuality" must be emphasised, would you use "hunin". Maybe when you would say "each and every" in English.

These 5 words are unusual in that they have "sandhi". Although always written the same, the final "n" is pronounced "ŋ" when the specified noun has an initial "k" or "g". It is pronounced "m" when the specified noun has an initial "p", "b" or "w". However even though "sandhi" occurs, the specifier remains a separate word from the noun that it specifies.

*"each" being followed by a singular noun and "all" being followed by a plural noun.

..... Some specifier - generic noun amalgamations

As would be expect, there has been some fusion between the specifiers and the generic nouns. The total paradigm is shown below ...

| judai | nothing | ʔindai | anything | andai | something | andaia | somethings | hundai | everything | hunindai | every single thing |

| jubu | nobody | ʔimbu | anybody/anyone | ambu | somebody/someone | ambua | some people | humbu | everybody | hunimbu | every single person |

| ʔinde | any day | ande | some day | andeu | some days | hunde | ever | huninde | every single day |

Other amalgamations that occur are ...

| juku | never | juha | nowhere | jumyan | no type of | juwe | in no way |

Note that it is considered bad style to have a junandau as the O argument. Instead the verb should be negated, and the "any"-word should be used.

..... The relativizers

The relativizer in béu is ʔà. This takes all the pilana the same as a normal noun.

the basket ʔapi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ʔala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman ʔaye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town ʔafi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad ʔalya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

the boat ʔalfe you have just jumped is unsound

báu ʔás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

nambo ʔàn she lives is the biggest in town. báu ʔàn dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police*

báu ʔaho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife ʔage he severed the branch is a 100 years old

The old woman ʔaji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy ʔaco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

When the relative clause is giving extra information, the relativizer in is ʔài and a slight pause comes before it.

There is another relativized in béu that refers back to a whole proposition. In English "which" is sometimes given this function. For example ...

1) ... John had completely forgotten his wedding anniversary which really annoyed his wife.

béu uses nài in a similar way to how which is used in the above example. Also the same shorthand form is used for nài and nái. However no misunderstanding is possible since nài always has a pause before it (how do I do a comma ?) and nái always is immediately after a noun.

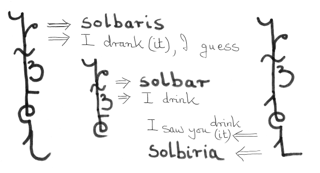

..... The R-form of the verb

So far we haven't said much about the verb as such, although we have come across the infinitive (gomia).

We will discuss the most-used form of the verb in this section, the R-form. But first we should introduce a new letter.

Above it is shown appearing in some active verbs. Just remember to put an extra little florish on the "r" when it occurs word finally, just to distinguish it from word final "j".

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the R-form of the verb.

So if you hear "r" or see the above symbol, you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause. (definition of a clause (semo) = that which has one "r" ... ??? )

O.K. ... the R-form is built up from the gomia*.

1) the final vowel is deleted from the gomia.

*Excepts in rare cases (see "Adjectives and how they pervade other parts of speech")

... Slot 1

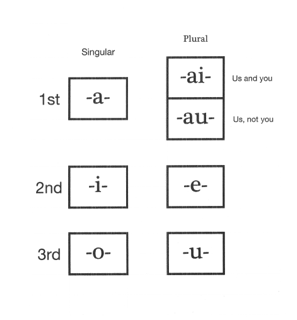

2) one of the 7 vowels below is added.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the Western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she). In the béu linguistic tradition they are called cenʔo-markers. (cenʔo = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play)

These markers represent the subject (the person that is performing the action). Whenever possible the pronoun that represents the subject is dropped, it is not needed because we have that information inside the verb with the cenʔo-markers.

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one must be used when the people performing the action included the speaker, the spoken to and possibly others. The lower one must be used when the people performing the action include the speaker, NOT the person spoken to and one or more 3rd persons.

Note that the ai form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

... Slot 2

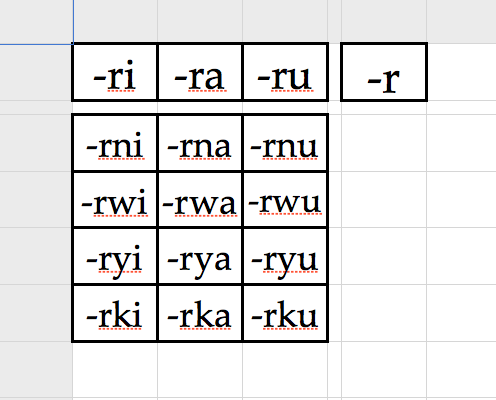

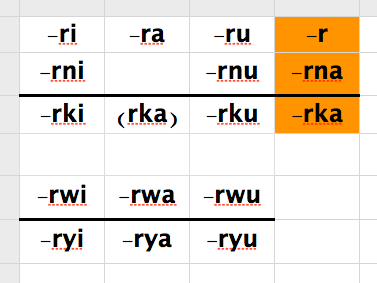

3) now one of the 16 markers shown below is added. 16 is quite a respectable number, as far as tense/aspect markers go.*

Now these markers represent what are called tense/aspect markers in the Western linguistic tradition. In the béu linguistic tradition, they are called gwomai or "modifications". (gwoma = to alter, to modify, to adjust, to change one attribute of something).

The table above has the gwoma arranged according to form. The two arrays below have the gwoma arranged according to meaning. The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have one entry enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a negative present tense negative you would express it periphrastically ... you would use the tenseless negative -rka followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Looking at the upper table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... i for the past, a for the present and u for the future.

-ri ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

-ra ... Should only be used if the action is happening NOW. English uses "to be xxxing". For example doikara = I am walking ... (doika = to walk)

-ru ... This is the future tense.

-r ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly".

The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school), Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). Actually in béu the pattern is broken a bit, in that -rna has NOTHING to do with the activity going on at the time of speech, it is actually a tenseless habitual. Also béu and English behave the same in the following way ... whereas by logic we should use doikarna in "I walk (to school everyday)", in fact doikar is used. doikarna would be used only if we were going on to MENTION some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift)

doikarna = "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use doikar

-rnu ... Now English doesn't have a future habitual. But if it did it would have a roll. For instance, suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In béu you would answer doikarnu.

The next row expresses the perfect tense.

While the perfect tense, logically this doesn't have that much difference from the past tense it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John. And think about the difference in meaning between "she has fallen in love" and "she fell in love" ... the first one means "she is in love" while the second one just talks about some of her history.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

Easy to translate into English ... doikorwi = He/she had walked ... doikorwa = He/she has walked ... doikorwu = He/she will have walked

The next row expresses the "not yet" tense.

Easy to translate into English ... doikoryi = He/she had not yet walked ... doikorya = He/she hasn't walked yet ... doikoryu = He/she will not have walked

Notice that the English translation, doikoryu is just the negative of doikorwu. Interesting eh ? In fact these two aspects can be in many ways regarded as the negatives of each other, although in English only the future tense gives the surface forms this way.

Which leads us on to the next row. This row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2 (that is right, row 2 does not have its own negative).

Just as -rna does not specify the present tense but instead gives a tenseless habitual, -rka gives a tenseless negative.

Easy to translate into English ... doikorki = He/she didn't walk ... doikorka = He/she doesn't walk ... doikorku = He/she will not walk

You may have noticed that the béu letter that negates verbs is very similar to the Chinese character that negates verbs (bù). This is pure coincidence.

By the way, the béu terms for the five aspects represented by these 5 rows are ... baga, dewe, pomo, fene, and liʒi.

*But even with 16 tense/aspect markers, not EVERY situation can be exactly expressed.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out" (using the progressive plus the perfect aspects). The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" (or working out over some period of time) to build up muscles. béu has no tense/aspect marker so appropriate.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

By the way, in the above example, the muscular schoolmate would use the r form of the verb plus the béu equivalent of "now", to explain his present condition. Good enough.

... Slot 3

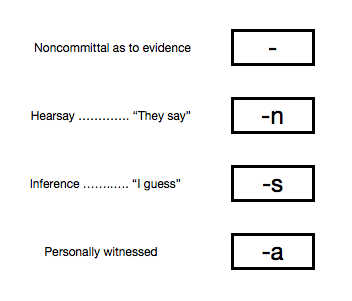

4) and finally one of the 4 teŋko-markers shown below is added.

teŋkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate" ... teŋko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. As evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In béu there are 4 evidential suffixes. One is what is called a zero suffix. And in meaning it gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based.

a) doikori = He/she walked ... this is neutral. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is saying what he is saying.

b) doikorin = They say he/she walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

c) doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow.

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The fourth tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

d) doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself".

This last teŋko can only be used with one of the gwomai . It can ONLY be used with the plain passed tense form i.

An o is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s".

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences