Béu : Chapter 5

..... Word order and definiteness

An interesting concept. The English language usage is;-

1) unknown to speaker and listener ... "I want to buy a dog"

2) known to speaker but unknown to listener ... "I read a book yesterday" ..... however if the speaker is going to reveal more about "book" he would say "I read this book yesterday"

3) unknown to speaker but known to listener ... "that dog that bit you yesterday was put down" .... or equally valid ... "the dog that bit you yesterday was put down"

The question here is, of course, if the dog is "totally" unknown to the speaker ... why is here speaking about it ... ah, we must go deeper

4) known to speaker and listener ... "I read the Bible yesterday"

Or consider this Norwegian, getting more definite in six easy steps.

5) She wants to marry a Norwegian ............. Could be any Norwegian. "She" does not even have any definite Norwegian in mind.

6) She wants to marry a Norwegian ............. Unknown to speaker and listener. But "she" has her eye on a particular Noggie.

7) She wants to marry some Norwegian ..... Not any Norwegian but the speaker known very little about him and the listener nothing.

8) She wants to marry a Norwegian** ........ Known to speaker but unknown to listener

9) She wants to marry this Norwegian ........ Known to speaker but unknown to listener

10) She wants to marry that Norwegian ....... Known to speaker and listener

9) and 10) can be said to be "half-definite" (my own term) The Norwegian is known but as a sort of peripheral character that hasn't as yet impinged on the consciousness* of the interlocutors that much. As/if he becomes more into focus in the interlocutors lives he will, of course, become, the Norwegian (or more probably Oddgeir or Roar or what have you).

11) She wants to marry the Norwegian ... As definite as you can get, I guess.

The use of this and that for "half-definite" makes sense ... it is iconic. "This thing" is near the speaker hence seen, touched, smelt by the speaker ... known to the speaker.

"That thing" is out in the open, hence experienced/known to both speaker and listener.

*Or the world-model that we each build up inside our heads.

**Notice that "She wants to marry a Norwegian" is ambiguous ... it could either have the implications of either 5), 6) or 8).

But enough of English. béu makes a noun more definite by putting it further to the left. To have an obligatory a or the in front of every noun is wasteful. However non-obligatory particles (such as "some" are fine)

Basically if a noun or noun phrase is to the left of the verb* it is definite, if it is to the right it is indefinite. For example ;-

báus timpori glà = The man hit a woman

glà timpori báus = A man hit the woman

However this rule does not effect proper names and pronouns. They are always definite so they can wonder anywhere in the clause and it doesn't make any difference.

*When I say verb here I am not counting the three copula's. They always have the order

Copula-subject copula copula-complement

Also dependent clauses have fixed word order ???

..... How to make a clause negative and how to focus the negativity on one element

ós jene timporwa or jene timporwa = He has hit Jane

ós jene timporya or ós jene timporya = He has not yet hit Jane

Question ... osfoi jene timpori = "Did he hit Jane"

?

?

Question ... osfoi jene timporwa =1) "Has he hit Jane yet" or 2)Has he hit Jane

Answer ... timporya = "not yet" ... the person answering still expects him to hit her ... The answerer reads the question as 1)

Answer ... timporki = 'he didn't" ... the person answering doesn't expects him to hit her now ... The answerer reads the question as 2)

This negates the complete clause. But what do you do if you want to negate one element in the clause. Well again the free word order of béu is again used. The word that you want to negate is moved between mó and the verb. So for example ;-

mó pás timparta jene = It wasn't me that hit Jane (it was that big guy over there)

pás mò jene timparta = It wasn't Jane that I hit (it was Mary)

Notice that it is not possible to focus everything. But that is not really important, it is always possible to add extra stress to the element you want to focus, just as we do in English.

..... And not forgetting negative questions

pasfoi timparki jene or timparkivoi jene = "I didn't hit Jane ?" or "I haven't hit Jane, have I ?"

If this question is answered aiwa (yes) it means "I haven't hit Jane" => pás timparki jene or timparki jene

If this question is answered aiya (no) it means "I have hit Jane" => pás timpari jene or timpari jene

Just a little thing to keep in mind. This is the opposite of normal English usage, but in accordance with most languages in the world.

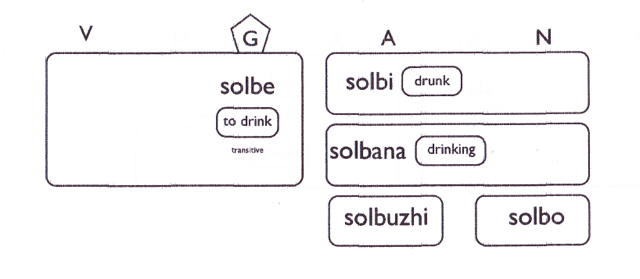

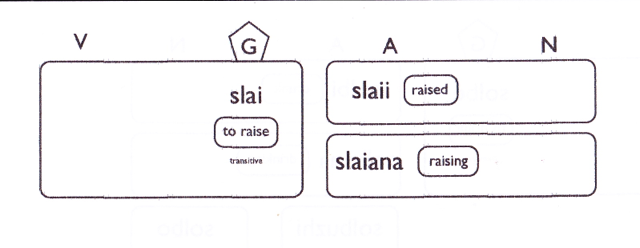

..... Verbs and how they pervade other parts of speech

slaii is pronounced as two syllables ... as you would say "sly "e" " ... glottal stop between the syllables ... quite easy to say.

slaianais pronounced as three syllables ... slai ... a ... na ... also easy to say.

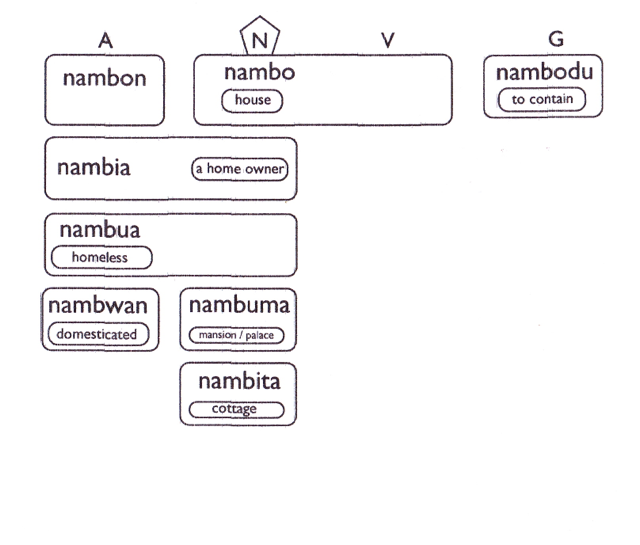

................. Nouns and how they pervade other parts of speech

nambo

nambo meaning house is a fairly typical non-single-syllable noun and we can use it to demonstrate how béu generates other words from nouns.

nambodu

Not many nouns can be used as verbs. However when an action is associated to a certain noun, usually, with no change of form, it can be used as a verb. For example lotova means bicycle and you get lotovarwi meaning "I used to ride my bicycle". For the infinitive, du must be affixed to the basic form.

The meaning given to the verb nambo is arrived at through metaphor, it is not so straight forward as the bicycle example.

The use of all tools can be expressed in a similar manner to lotova.

nambon

Sometimes in English a bare noun can be used to qualify another noun (i.e. it can act as an adjective). For example in the phrase "history teacher", "history" has the roll usually performed by an adjective ... for example, "the sadistic teacher". This can never happen in béu, the noun must undergo some sort of change. The most common change for nambo is it to change into its genitive form nambon as in pintu nambon "the door of the house". Other changes that can occur are the affixation of -go or -ka. These are used with certain nouns more than others. They are not used that much with the noun nambo so I haven't included them in the chart above. You could use the forms nambogo or namboka if you wanted tho' (they would mean "house-like"). Maybe you would use one of these terms in a joke ... it would stike the listener as slightly odd however.

nambia

This is a very common derivation. Nearly all nouns can take this transformation.

nambia is an adjective meaning "having a home". And its use as a noun is quite common as well, in which case it would probably be translater as "a home owner"

nambua

Also a very common derivation. The opposite of nambia.

nambua means homeless or the homeless

Note that although ia and ua are exact opposites, the usage of the words produced from these affixes do not completely mirror each other. It all depends oner what the base word is.

For example, in this case, the form nambia is a bit rarer than nambia. Also nambua is used more often as an adjective than as a noun, while nambia is used more often as a noun than an adjective.

nambuma

Many of the worlds languages have a suffix that has this roll. Called an "augmentative" in the Western linguistic tradition. Does not really come into play in English but quite common in béu. As well as some basic forms that appear regularly in their augmentative version, any noun can receive this affix. But of course it will stick out if it is not commonly used.

nambita

The opposite of nambuma. Called an "diminutive" in the Western linguistic tradition. In béu it is often used to show that the speaker feels affection for the noun so transformed. There is no trace of the opposite for the augmentative : nobody would use the augmentative to show repulsion.

nambwan

The form changes that produce nambia, nambua, nambuma, nambita, *nambija are *nambeba affected by deleting the final vowel (or diphthong) and then adding the relevant affix. However with this change of form this is not always possible to delete the final vowel (example). In this example it is possible. In fact it is possible if the final consonant of the base word is j, b, g, d,c, s, k, t, l or m.

wan is affixed to a few nouns, a few adjectives plus a few. Its has the sense of "tending towards","accustomed to" or "addicted to".

| ái | white | aiwan | faded |

| lozo | grey | lozwan | grizzled |

| pà | I | pawan | selfish |

| mama | mother | mamwan | motherbound |

| nambo | house | nambwan | domesticated |

| toili | book | toilwan | bookish |

By the way nambwan means domestic or domesticated. Nearly always when you come across the word it is referring to animals.

Other derivations that are not possible with nambo

I have already mentioned nambogo and namboka which while possible, are not at all common. Also I will mention three other derivations that are quite common however can not occur with nambo.

1) -ija is affixed to the names of animals and give a word meaning the young of that animal. For example;-

huvu = sheep

huvija = lamb

mèu = cat

meuja = kitten

2) -eba is an affix that produces a word meaning "a set of something" where the base word is considered as a central/typical member of that set. For example;-

baiʔo = spoon

baiʔeba = cutlery

= chair

= furniture

nambeba could represent a set comprising (houses, huts, skyscrapers, apartment buildings, government buildings etc etc.), however this is already covered by bundo (derived from the verb bunda "to build").

3) -we ... Well the status of this one can be analysed in two ways. It could be said to be the same as the affixes mentioned above. An affix that generates an adverb* with the meaning "to act in the manner of xxxx". OK the nouns that are used with this affix tend to do something (to move) and as houses do not do much, I can not demonstrate using nambo.

Let us take deuta meaning "soldier". The word deutawe would be an adverb meaning "in the manner of a soldier". Note that if this is an affix. it has the form CV and hence does not overwrite the final vowel of the base word (unlike the other affixes).

An alternative way to look at this is a result of the "word-building" process (see section ???)

wé deutan means "way of a soldier" or "manner of a soldier".

Now if we follow the "word-building rules"

1) The genitive suffix n is dropped

2) The first syllable of the first word is dropped.

3) The remainder of the first word is affixed to the second word.

We get the form deutawe (wé being monosyllabic, we obviously can not delete its first syllable)

Probably the first analysis is correct, and we should keep fé deutan as a noun phrase, and deutawe as an adverb.

* I haven't mentioned adverbs before. They are a separate part of speech, but a part of speech that has a very marginal roll. For the most part, adverbs are the same as adjectives.

báu

..... A bit about adverbs

If an adjective comes immediately after a verb (which it normally would) it is known to be an adverb. For example saco means "slow" but if it came immediately after a verb it would be translated as "slowly". However if we add -ve to it so we get the form sacowe the adverb can move around the utterance ... wherever it wants to go.

-we can also be affixed to a noun and also produce an adverb. For example ;-

deuta means "soldier"

deutawe means "in the manner of a soldier"

as in doikora deutawe = he walk like a soldier

So that is basically all there is to adverbs. In the Western linguistic tradition many other words are classified as adverbs. Words such as "often" and "tomorrow" etc. etc.

In the béu linguistic tradition all these words are classified as particles, a hodge podge collection of words that do not fit into the classes of noun (N), adjective (A), verb (G) or adverb.

..... The 8 possessive infixes

In the above section we learnt how to say "mine", "yours", etc. etc.. But how do we say "my", "your", etc. etc.

Well these words (which would be considered adjectives in the béu linguistic tradition) are represented by infixes. The table below shows how it works.

| my coat | kaunapu |

| our coat ("our" includes "you") | kaunayu |

| our coat ("our excludes "you") | kaunawu |

| your coat | kaunigu |

| your coat (with "you" being plural) | kauneju |

| his/her coat | kaunonu |

| their coat | kaununu |

| xxxx own coat | kaunitu |

It can be seen that the infixes are the same as the plain pronouns, but the order of the consonant and vowel are swapped over.

There could also be another entry in the table above. That is the infix -it- (this is the possessive equivalent of the reflexive pronoun tí (see above). It is probably easiest to explain -it- by way of example;-

polo hendoru kaunitu = Paul will wear his coat (To be absolutely specific "Paul will wear his own coat")

polo hendoru kaunonu = Paul will wear his coat (To be absolutely specific "Paul will wear someone else's coat")

A thing to note is that you can not insert an infix into a monosyllable word. You could not say *glapa for "my woman" but would have to say glá nà pà

..... The transitivity of verbs in béu

All languages have a Verb class, generally with at least several hundred members.

Leaving aside copula clauses, there are two recurrent clause types, transitive and intransitive. Verbs can be classified according to the clause type they may occur in: (a) Intransitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of an intransitive clause; for example, "snore" in English. (b) Transitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of a transitive clause; for example, "hit" in English. In some languages, all verbs are either strictly intransitive or strictly transitive. But in others there are ambitransitive (or labile) verbs, which may be used in an intransitive or in a transitive clause. These are of two varieties: (c) Ambitransitives of type S = A. An English example is "knit", as in "SheS knits" and "SheA knits socksO". (d) Ambitransitives of type S = O. An English example is "melt", as in "The butterS melted" and "SheA melted the butterO".

English verbs can be divided into the four types mentioned above. béu verbs however can only be divided into two types, a) Intransitive, and b) Transitive. In this section it will be shown how the four English types of verb map into the two béu types. (Of course there is nothing special or unique about English ... other than the fact that a reader of this grammatical sketch will already be familiar with English)

Intransitive

..

An intransitive verb in English => an intransitive verb in béu

..

An example of an intransitive verb in English is "laugh". This is also an intransitive verb in béu. In a clause containing an intransitive verb, the only argument that you have is the S argument.

By the way ... some concepts that are adjectives in English are primarily intransitive verbs in béu, for example ;- to be angry, to be sick, to be healthy etc. etc.

Ambitransitive of type S=O

..

| x) An intransitive in béu | |

| An "ambitransitive of type S=O" => | y) A pair of verbs, one being intransitive and one being transitive |

| z) A transitive in béu |

..

x) "Ambitransitive verbs of type S=O" which have greater frequency in intransitive clauses, are intransitive verbs in béu.

For example ;- flompe = to trip, (ò)S flomporta = She has tripped

y) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which are frequent in both transitive and intransitive clauses, are represented as a pair of verbs in béu, one of which is intransitive and one transitive. There are a few hundred béu verbs that come in pairs like this. One should not be thought of as derived from the other; each form should be considered equally fundamental. All the pairs have the same form, except the transitive one has an extra "l" before its final consonant.

For example hakori kusoniS = his chair broke : (pás)A halkari kusoniO = I broke his chair :

z) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which have greater frequency in transitive clauses, are transitive vebs in béu.

For example ;- nava = to open, (pás)A navaru pintoO = I am going to open the door

Ambitransitive verbs of type S=A and Transitive verbs

. .

| An "ambitransitive of type S=A" | |

| or | => A transitive in béu |

| A transitive verb in English |

. .

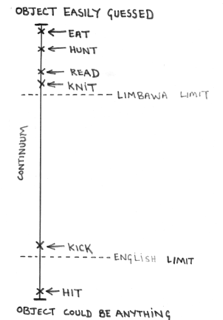

I am taking transitive and ambitransitive of type (S=A) together as I consider them to be basically the same thing but tending to opposite ends of a continuum.

Consider the illustration below.

At the top (with the "objects easily guessed") are verbs that are normally designated "ambitransitive of type S=A".

At the bottom (with the "objects could be anything") are verbs that are normally designated "transitive".

.

.

Considering the top first. One can have "IA eat applesO" or we can have "IS eat"

Then considering the bottom. One can have "IA hit JaneO" but you can not have "*IS hit"

Moving up from the bottom. One can imagine a situation, for example when showing a horse to somebody for the first time when you would say "SheS kicks". While this is possible to say this, it is hardly common.

As we go from the top to the bottom of the continuum;-

a) The semantic area to which the object (or potential object if you will) gets bigger and bigger.

b) At the bottom end the object becomes is more unpedictable and hence more pertinent.

c) As a consequence of a) and b), the object is more likely to be human as you go down the continuum.

béu considers it good style to drop as many arguments as possible. In béu all the verbs along this continuum are considered transitive. Quite often one or both arguments are dropped, but of course are known through context. If the O argument is dropped it could be known because it was the previously declared topic (however more often the A argument is the topic tho', and hence dropped, represented by swe tho' as its case marking can not be dropped), it could be because the verb is from the top end of the continuum and the action is the important thing and the O argument or arguments just not important, or the dropped argument could be interpreted as "something" or "somebody", or it could be a definite thing that can be identified by the discouse that the clause is buried in.

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences