Béu : Chapter 3

To give and to receive

kyé = to give ... jonosA kyori jeneye toiliO = John gave a book to Jane "or" John gave Jane a book

bwò = to receive, to get ... jeneA bwori toiliO (jonovi) = Jane got a book (from John)

These two words are also used for valency changing operations.

jonos kyori paye solbe moze = John made me drink the water ... called the causative construction in linguistic jargon

moze bwori solbe (jenevi) = The water was drunk (by Jane) ... called the passive construction in linguistic jargon ... It is used when the "A" argument is unknown or unimportant.

Another type of noun phrase

In chapter 2 we went over the construction of a noun phrase. Here we introduce a second type of noun phrase*.

This has at its heart a gomua. It can consist of one word which will be gomua. However more involved gomuaza exist. All these gomuaza have an equivalent clause, which of course have gomia as their heart.

The clause has free word order. However the word order of the gomuaza is fixed. For example;-

(pás) solbari moze sacowe or (pás) solbari saco moze => I drank the water quickly

As a gomuaza this clause would be pà solbe moze saco => My drinking of the water quickly. ... Note that pà can not be dropped. Also it is in its plain or unmarked form (i.e. no -s stuck on).

Note the word order ... "A" argument followed by gomua followed by "O" argument followed by adverb (any other peripheral arguments are stuck on at the end).

*Actually in the béu linguistic tradition, the noun phrase introduced in chapter 2 is called a ???? . And the noun phrase introduced above is called gomuaza

The copula's

The 2 verbs sàu and gaza are special verbs. (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... They are called copulas... in Latin "copulare" meant "to tie", so a copula is a verb that ties. In béu they differ from normal verbs, in that they require a specific word order. Also s (the ergative case) is never suffixed to a noun, as normally happens when a verb is associated with two nouns.

..... gaza ... the copula of existence

The copula complement of gaza ia always a noun or a noun phrase. It is how you say "there is ... "

gaza is similar to sàu in that it takes the 9 verb modifiers but 3 of them are wildly irregular. It is the same 3 tense/aspect forms that are irregularin the sàu copula. Namely ;-

*gazora => ʔá meaning "there is"

*gazori => ʔái meaning "there was"

*gazoru => ʔáu meaning "there will be"

Actually while theoretically gaza can have the full range of modifiers enjoyed by a normal verb, in reality all forms other than ʔá, ʔái, ʔáu are extremely rare. Occasionally you come across the "infinitive" gaza.

There is no word that corresponds to "have". The usual way to say "I have a coat" is "there exists a coat mine" = ʔá kaunu nà pà

Internal possessives are not allowed in the nouns introduced with gaza. That is, you can not say *ʔá kaunapu, but must say ʔá kaunu nà pà (I have a coat)

As I said above, gaza always comes with one noun. If it comes with an adjective, then that adjective can be considered a noun (well this is one way to look at it)

Also note that when the noun is a noun as opposed to an adjective, ??? , it is always indefinite.

pona = cold (an adjective), ponan = coldness (a noun)

ʔá ponan = "it is cold"

ʔá pona paye meaning "I feel cold" (word for word ... "there is coldness to me")

There is fixed word order : it is always gaza followed by the noun or NP.

The three irregular forms have their own negative marker. ya is stuck on to the end of the copula.

ʔaya ponan = "it is not cold"

Note that the word ʔaya (there is not) and ʔaiya (there was not) are very close to each other phonetically. However the middle part of the second word takes twice as long as the middle part in the first word : they are phonetically quite distinct.

The particles lói (probably) and màs (maybe) normally, come before the verb that they qualify. However the 3 irregular forms of gaza really like to come clause initially. Hence lói and màs immediately follow the verb.

ʔáu lói ponan = It will probably be cold

Also the evidentials are affixed to the wild forms, just as normal.

ʔaunya lói pona = They say it will probably not be cold

ʔaunya.foi lói pona = Do they say it will probably not be cold ?

..... sàu ... the main copula

sàu is the béu copula. That is it is the equivalent of "to be" in English, whish has such forms as "be", "is", "was", "were" and "are".

This verb is slightly irregular in béu as well. The three forms *sari, *saru and *sara which you would expect to see, are replaced with rì, rù and rà

Notice that person and number is not included in these three irregular forms, so it is sometimes necessary to have a pronoun in situations where it would normally be dropped.

Actually rà is usually missed out completely.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... gì mò rà moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... pà rà moltai = I am a doctor

Notice that rà is always used when you have mò the negative particle. This particle must always be directly in front of a verb, so rà must be expressed.

Another situation where rà tends to be used is when the subject or the copula complement are long trains of words. For example ????????

The evidentials are appended to the wild forms as normal. So we have ràn, ràs, rìn, rià, rìs, rùn and rùs.

..... láu ... the change of state copula

láu = to become, to get, recieve

lí = became

lá = becomes

lú = will become

hái = to give

láu hauʔe = to become beautiful OR to become a beautiful woman

jene lái timporu jono.vi = Jane will be hit by John

hái tí (sàu) haiʔe = to make yourself (to be) beautiful

hái jene flompe = to make Jane trip

hái jono.ye timpa jene = to make John trip Jane ... note that the A argument takes the pilana -ye

..... Word order and definiteness

Basically if a noun or noun phrase is to the left of the verb* it is definite, if it is to the right it is indefinite. For example ;-

bau?s timpori gla? = The man hit a woman

gla? timpori bau?s = A man hit the woman

However this rule does not effect proper names and pronouns. They are always definite so they can wonder anywhere in the clause and it doesn't make any difference.

*When I say verb here I am not counting the three copula's. They always have the order

Copula-subject copula copula-complement

..... How to ask a YES/NO question and how to focus the question to one element

To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a YES/NO answer), you stick on the enclitic foi to the end of the first word in the sentence. This enclitic is unusual in that when attached to a word ending in a vowel (most words) the "f" doesn't change to a "v". So in the above example, we would get ;-

glafoi timpori bau?s = "Was it a man that hit the woman"

If you want to query a particular element in the clause and not the clause as a whole, you stick foi on to the element that you want to query.

gla? timporifoi bau?s = Did a man hit the woman ? (I thought that he had kicked her)

gla? timpori bausfoi = Was it a man that hit the woman ? (I thought it was a boy)

Note that in this particular example, we can not question the element "the woman". (Because we can not drag gla? away from its position as the first element in the clause) However in 9 out of 10 cases it is possible to question any element in a clause. For example it would be possible to do so if both nouns were definite or both were indefinite.Also it would be possible if the other noun in the clause was a pronoun or a proper name. Also For example ;-

gla? timpori pas? = I hit the woman

glafoi timpori pas = Did I hit the woman ?

pas? glafoi timpori = Was it the woman that I hit ?

Notice that often English relies on stress, to bring attention to the item being queried.

Entire NPs can go before foi for example ;-

sa báu jutu defoi timpori jene = was it that big guy there that hit Jane.

..... How to make a clause negative and how to focus the negativity on one element

Usually the negative particle goes directly before the verb.

pás mò timparta jene = I have not hit Jane

This negates the complete clause. But what do you do if you want to negate one element in the clause. Well again the free word order of béu is again used. The word that you want to negate is moved between mó and the verb. So for example ;-

mó pás timparta jene = It wasn't me that hit Jane (it was that big guy over there)

pás mò jene timparta = It wasn't Jane that I hit (it was Mary)

Notice that it is not possible to focus everything. But that is not really important, it is always possible to add extra stress to the element you want to focus, just as we do in English.

..... And not forgetting negative questions

pas.foi mò timparta jene = I haven't hit Jane, have I ?

If this question is answered aiwa it means "you haven't hit Jane"

If this question is answered aiya it means "you have hit Jane"

Just a little thing to keep in mind. This is the opposite of normal English usage, but in accordance with most languages in the world.

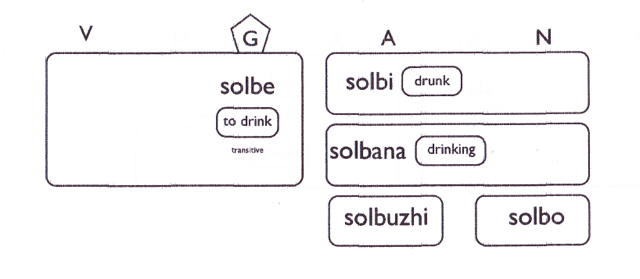

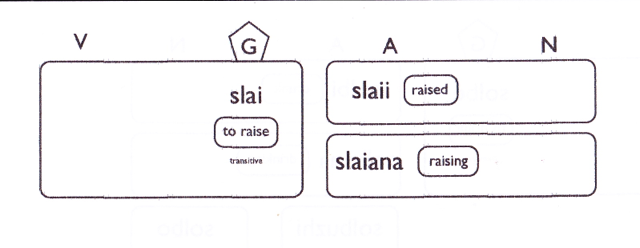

..... Verbs and how they pervade other parts of speech

slaii is pronounced as two syllables ... as you would say "sly "e" " ... glottal stop between the syllables ... quite easy to say.

slaianais pronounced as three syllables ... slai ... a ... na ... also easy to say.

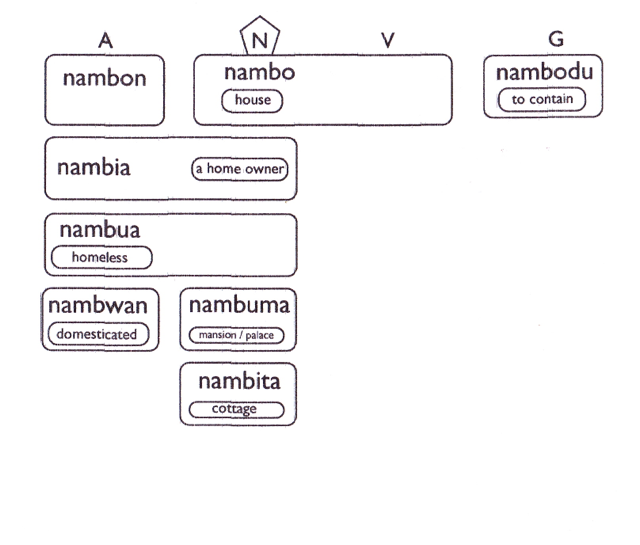

................. Nouns and how they pervade other parts of speech

nambo

nambo meaning house is a fairly typical non-single-syllable noun and we can use it to demonstrate how béu generates other words from nouns.

nambodu

Not many nouns can be used as verbs. However when an action is associated to a certain noun, usually, with no change of form, it can be used as a verb. For example lotova means bicycle and you get lotovarwi meaning "I used to ride my bicycle". For the infinitive, du must be affixed to the basic form.

The meaning given to the verb nambo is arrived at through metaphor, it is not so straight forward as the bicycle example.

The use of all tools can be expressed in a similar manner to lotova.

nambon

Sometimes in English a bare noun can be used to qualify another noun (i.e. it can act as an adjective). For example in the phrase "history teacher", "history" has the roll usually performed by an adjective ... for example, "the sadistic teacher". This can never happen in béu, the noun must undergo some sort of change. The most common change for nambo is it to change into its genitive form nambon as in pintu nambon "the door of the house". Other changes that can occur are the affixation of -go or -ka. These are used with certain nouns more than others. They are not used that much with the noun nambo so I haven't included them in the chart above. You could use the forms nambogo or namboka if you wanted tho' (they would mean "house-like"). Maybe you would use one of these terms in a joke ... it would stike the listener as slightly odd however.

nambia

This is a very common derivation. Nearly all nouns can take this transformation.

nambia is an adjective meaning "having a home". And its use as a noun is quite common as well, in which case it would probably be translater as "a home owner"

nambua

Also a very common derivation. The opposite of nambia.

nambua means homeless or the homeless

Note that although ia and ua are exact opposites, the usage of the words produced from these affixes do not completely mirror each other. It all depends oner what the base word is.

For example, in this case, the form nambia is a bit rarer than nambia. Also nambua is used more often as an adjective than as a noun, while nambia is used more often as a noun than an adjective.

nambuma

Many of the worlds languages have a suffix that has this roll. Called an "augmentative" in the Western linguistic tradition. Does not really come into play in English but quite common in béu. As well as some basic forms that appear regularly in their augmentative version, any noun can receive this affix. But of course it will stick out if it is not commonly used.

nambita

The opposite of nambuma. Called an "diminutive" in the Western linguistic tradition. In béu it is often used to show that the speaker feels affection for the noun so transformed. There is no trace of the opposite for the augmentative : nobody would use the augmentative to show repulsion.

nambwan

The form changes that produce nambia, nambua, nambuma, nambita, *nambija are *nambeba affected by deleting the final vowel (or diphthong) and then adding the relevant affix. However with this change of form this is not always possible to delete the final vowel (example). In this example it is possible. In fact it is possible if the final consonant of the base word is j, b, g, d,c, s, k, t, l or m.

wan is affixed to a few nouns, a few adjectives plus a few. Its has the sense of "tending towards","accustomed to" or "addicted to".

| ái | white | aiwan | faded |

| lozo | grey | lozwan | grizzled |

| pà | I | pawan | selfish |

| mama | mother | mamwan | motherbound |

| nambo | house | nambwan | domesticated |

| toili | book | toilwan | bookish |

By the way nambwan means domestic or domesticated. Nearly always when you come across the word it is referring to animals.

Other derivations that are not possible with nambo

I have already mentioned nambogo and namboka which while possible, are not at all common. Also I will mention three other derivations that are quite common however can not occur with nambo.

1) -ija is affixed to the names of animals and give a word meaning the young of that animal. For example;-

huvu = sheep

huvija = lamb

mèu = cat

meuja = kitten

2) -eba is an affix that produces a word meaning "a set of something" where the base word is considered as a central/typical member of that set. For example;-

baiʔo = spoon

baiʔeba = cutlery

= chair

= furniture

nambeba could represent a set comprising (houses, huts, skyscrapers, apartment buildings, government buildings etc etc.), however this is already covered by bundo (derived from the verb bunda "to build").

3) -we ... Well the status of this one can be analysed in two ways. It could be said to be the same as the affixes mentioned above. An affix that generates an adverb* with the meaning "to act in the manner of xxxx". OK the nouns that are used with this affix tend to do something (to move) and as houses do not do much, I can not demonstrate using nambo.

Let us take deuta meaning "soldier". The word deutawe would be an adverb meaning "in the manner of a soldier". Note that if this is an affix. it has the form CV and hence does not overwrite the final vowel of the base word (unlike the other affixes).

An alternative way to look at this is a result of the "word-building" process (see section ???)

wé deutan means "way of a soldier" or "manner of a soldier".

Now if we follow the "word-building rules"

1) The genitive suffix n is dropped

2) The first syllable of the first word is dropped.

3) The remainder of the first word is affixed to the second word.

We get the form deutawe (wé being monosyllabic, we obviously can not delete its first syllable)

Probably the first analysis is correct, and we should keep fé deutan as a noun phrase, and deutawe as an adverb.

* I haven't mentioned adverbs before. They are a separate part of speech, but a part of speech that has a very marginal roll. For the most part, adverbs are the same as adjectives.

báu

..... A bit about adverbs

If an adjective comes immediately after a verb (which it normally would) it is known to be an adverb. For example saco means "slow" but if it came immediately after a verb it would be translated as "slowly". However if we add -ve to it so we get the form sacowe the adverb can move around the utterance ... wherever it wants to go.

-we can also be affixed to a noun and also produce an adverb. For example ;-

deuta means "soldier"

deutawe means "in the manner of a soldier"

as in doikora deutawe = he walk like a soldier

So that is basically all there is to adverbs. In the Western linguistic tradition many other words are classified as adverbs. Words such as "often" and "tomorrow" etc. etc.

In the béu linguistic tradition all these words are classified as particles, a hodge podge collection of words that do not fit into the classes of noun (N), adjective (A), verb (G) or adverb.

..... The 8 possessive infixes

In the above section we learnt how to say "mine", "yours", etc. etc.. But how do we say "my", "your", etc. etc.

Well these words (which would be considered adjectives in the béu linguistic tradition) are represented by infixes. The table below shows how it works.

| my coat | kaunapu |

| our coat ("our" includes "you") | kaunayu |

| our coat ("our excludes "you") | kaunawu |

| your coat | kaunigu |

| your coat (with "you" being plural) | kauneju |

| his/her coat | kaunonu |

| their coat | kaununu |

| xxxx own coat | kaunitu |

It can be seen that the infixes are the same as the plain pronouns, but the order of the consonant and vowel are swapped over.

There could also be another entry in the table above. That is the infix -it- (this is the possessive equivalent of the reflexive pronoun tí (see above). It is probably easiest to explain -it- by way of example;-

polo hendoru kaunitu = Paul will wear his coat (To be absolutely specific "Paul will wear his own coat")

polo hendoru kaunonu = Paul will wear his coat (To be absolutely specific "Paul will wear someone else's coat")

A thing to note is that you can not insert an infix into a monosyllable word. You could not say *glapa for "my woman" but would have to say glá nà pà

..... The transitivity of verbs in béu

All languages have a Verb class, generally with at least several hundred members.

Leaving aside copula clauses, there are two recurrent clause types, transitive and intransitive. Verbs can be classified according to the clause type they may occur in: (a) Intransitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of an intransitive clause; for example, "snore" in English. (b) Transitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of a transitive clause; for example, "hit" in English. In some languages, all verbs are either strictly intransitive or strictly transitive. But in others there are ambitransitive (or labile) verbs, which may be used in an intransitive or in a transitive clause. These are of two varieties: (c) Ambitransitives of type S = A. An English example is "knit", as in "SheS knits" and "SheA knits socksO". (d) Ambitransitives of type S = O. An English example is "melt", as in "The butterS melted" and "SheA melted the butterO".

English verbs can be divided into the four types mentioned above. béu verbs however can only be divided into two types, a) Intransitive, and b) Transitive. In this section it will be shown how the four English types of verb map into the two béu types. (Of course there is nothing special or unique about English ... other than the fact that a reader of this grammatical sketch will already be familiar with English)

Intransitive

..

An intransitive verb in English => an intransitive verb in béu

..

An example of an intransitive verb in English is "laugh". This is also an intransitive verb in béu. In a clause containing an intransitive verb, the only argument that you have is the S argument.

By the way ... some concepts that are adjectives in English are primarily intransitive verbs in béu, for example ;- to be angry, to be sick, to be healthy etc. etc.

Ambitransitive of type S=O

..

| x) An intransitive in béu | |

| An "ambitransitive of type S=O" => | y) A pair of verbs, one being intransitive and one being transitive |

| z) A transitive in béu |

..

x) "Ambitransitive verbs of type S=O" which have greater frequency in intransitive clauses, are intransitive verbs in béu.

For example ;- flompe = to trip, (ò)S flomporta = She has tripped

y) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which are frequent in both transitive and intransitive clauses, are represented as a pair of verbs in béu, one of which is intransitive and one transitive. There are a few hundred béu verbs that come in pairs like this. One should not be thought of as derived from the other; each form should be considered equally fundamental. All the pairs have the same form, except the transitive one has an extra "l" before its final consonant.

For example hakori kusoniS = his chair broke : (pás)A halkari kusoniO = I broke his chair :

z) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which have greater frequency in transitive clauses, are transitive vebs in béu.

For example ;- nava = to open, (pás)A navaru pintoO = I am going to open the door

Ambitransitive verbs of type S=A and Transitive verbs

. .

| An "ambitransitive of type S=A" | |

| or | => A transitive in béu |

| A transitive verb in English |

. .

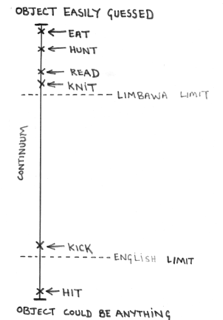

I am taking transitive and ambitransitive of type (S=A) together as I consider them to be basically the same thing but tending to opposite ends of a continuum.

Consider the illustration below.

At the top (with the "objects easily guessed") are verbs that are normally designated "ambitransitive of type S=A".

At the bottom (with the "objects could be anything") are verbs that are normally designated "transitive".

.

.

Considering the top first. One can have "IA eat applesO" or we can have "IS eat"

Then considering the bottom. One can have "IA hit JaneO" but you can not have "*IS hit"

Moving up from the bottom. One can imagine a situation, for example when showing a horse to somebody for the first time when you would say "SheS kicks". While this is possible to say this, it is hardly common*.

As we go from the top to the bottom of the continuum;-

a) The semantic area to which the object (or potential object if you will) gets bigger and bigger.

b) At the bottom end the object becomes is more unpedictable and hence more pertinent.

c) As a consequence of a) and b), the object is more likely to be human as you go down the continuum.

béu considers it good style to drop as many arguments as possible. In béu all the verbs along this continuum are considered transitive. Quite often one or both arguments are dropped, but of course are known through context. If the O argument is dropped it could be known because it was the previously declared topic (however more often the A argument is the topic tho', and hence dropped, represented by swe tho' as its case marking can not be dropped), it could be because the verb is from the top end of the continuum and the action is the important thing and the O argument or arguments just not important, or the dropped argument could be interpreted as "something" or "somebody", or it could be a definite thing that can be identified by the discouse that the clause is buried in.

* In béu "She kicks" would be ò (rà) lugaʃi from luga = "to kick" and the suffix ʃi, meaning "to tend to", "to be liable to" . .

Must, should, can + may

meski = is a noun meaning strong obligation or duty

senga = is a noun meaning weak obligation

olda = is a noun meaning ability

hempi is a noun meaning permission

It can be argued whether the above are geladi or nouns. But that doesn't matter.

When they act as verbs they must be followed by geladi. For example ;-

meskara timpa gla? de? = I must hit that woman

sengara timpa gla? de? = I ought to hit that woman

These word have a special negative.

meskara timpa gla? de? = I must hit that woman

Hold on this is no good, I want the special negative aiya

meskai timpara gla? de? = I must hit that woman

meskaiya timpara gla? de? = I must not hit that woman

This special negative can be used with a normal negative sometimes.

gla? de? oldaiya mo? humpora shokolate = That woman can not not eat chocolates. (meaning she can't resist them)

Positive and negative

Above we have used -ya to generate a negative meaning. This form is used in two other situations to give a negative meaning. In aiya meaning "no" and in kya meaning "don't". However there is also 3 situations where -ya or -ia have a positive meaning ... in fanfia (as oppopsed to fanfua), in kunjua (as opposed to kunja and in umutu as opposed to mutu. This is just the way things are.

The relative clause

béu has a relative clause construction which works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. A relative clause is a clause that qualifies a noun. It is introduced by a special particle, tà in béu. In English it is usually "that" but a number of other words can also be used. The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its pilana on the relativizer tà. For example ;-

glá tà bwàs timpori rà hauʔe = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful. ... If the clause that is qualifying the noun appeared in isolation, it would be - bwàs timpori glá ... glá is the O argument and hence is unmarked.

glá tà flompori rà hauʔe = The woman that tripped is beautiful. ... If the clause that is qualifying the noun appeared in isolation, it would be - glá flompori ... glá is the S argument and hence is unmarked.

bwà tàs timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly. ... If the clause that is qualifying the noun appeared in isolation, it would be - bwàs timpori glá ... bwà is the A argument and hence has pilana number 7 "-s", which is transferred to the relativized tà when bwà disappears.

The same thing happens with all the pilana*. For example ;-

the basket tapi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall tala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman taye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town tavi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad talya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

the boat talfe you have just jumped is unsound

bwà tàs timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

nambo taʔe she lives is the biggest in town.

bwà taho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife tatu he severed the branch is a 100 years old

the man tan dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police**

The old woman taji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy taco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

* Well all the pilana except -wa. This pilana sets the noun it qualifies to the status of "topic". The time for which a noun will retain its "topicality" is usually much longer than a clause.

**Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. n marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause.

The topic marker "wa" and the discourse strategy of dropping the topic.

English has what Dixon calls a S/A pivot construction. What that means is you can drop the A argument or the S argument if it is the same as the A argument or S argument in the previous clause. For example ;-

1) You can drop the A if it is the same as the S in the previous clause ... John saw Mary: John laughed => John saw Mary and laughed

2) You can drop the A if it is the same as the A in the previous clause ... John saw Mary : John hit Bill => John saw Mary and hit Bill

3) You can drop the S if it is the same as the S in the previous clause ... John entered : John sat down => John entered and sat down

4) You can drop the S if it is the same as the A in the previous clause ... John entered : John saw Mary => John entered and saw Mary

A small number of languages have a S/O pivot. That is you can drop the S argument or the O argument if it is the same as the S argument or O argument in the previous clause. (the Australian language Dyirbal is one example of this type of language).

Anyway, the above is just some side-information that I am giving you. béu has what I call a declared pivot construction. The "pivot" (or topic) in a discourse must be stated and from that point on all reference to that "pivot" is dropped, until a new "pivot" is declared.

You declare the topic by affixing wa to it when it is in S, A or O function. If it is in A function that the topic is declared then the s (ergative marker) is dropped. (However in the clause in which you declare a pivot can not have any dropped arguments ... if it is a transitive verb in the clause, and there in no argument with the ergative marker, then you can work out that it must be the argument marked by wa which is the A argument). From then on the topic is dropped until a new topic is declared. For example;-

1) giant.wa destroyed the castle on the hill

2) Then ø came down into the valley

3) There ø met a dwarf doing good works

4) The dwarf turned ø to stone

5) Dwarf.wa then climbed the mountain

6) ø gave succour to the people from the castle ...

It is the rule that the topic must be dropped. if the topic appears in a peripheral roll (pilana 1-> 14) then that pilana is attached to the verb.

For example ;-

1) Last night I saw Thomas

2) Thomas.wa (or o.wa) was very drunk

3) Mary had given.ye a bottle of Chevas Regal

How does this system mesh in with passives ? Particles that appear between clauses ? Particles that change the subject ?

You can see from 4) above, that this just doesn't work if you have labile verbs. In English "turned" is called a labile verb (ambitransitive is another name for this). That means it can be used in a transitive clause and in an intransitive clause. Foer example ;-

1) The dwarf turned the giant to stone ... transitive

2) The dwarf turned to stone ... intransitive

Changing transitivity

béu has 2 morphological ways to make all these type of verbs into transitive verbs ( see -at- and -az- causatives).

-AT- and -AZ-

tonzai = to awaken

tonzatai = to wake up somebody (directly) i.e. by shaking them

tonzazai = to wake up somebody (indirectly) i.e. by calling out to them

henda = to put on clothes

hendata = to dress somebody (for example, how you would dress a child)

hendaza = to get somebody to dress (for example, you would get an older child to dress by calling out to them)

The above methods of making a causative only apply to intransitive verbs. To make an transitive clause onto a causative the same method is used as English used. That is the entire transitive clause becomes a complement clause of the verb "to make".

In addition to the causative infixes shown above, there are many verb pairs such as poi = to enter, ploi = to put in, gau = to rise, glau = to raise, sai = to descend, slai = to lower

and in multisyllable words ... laudo = to wash (oneself), lauldo = to wash (something). The above are not really considered causatives. The infixing of the l is by no means productive. In fact you can not call it "infixing". Also in many cases the transitive verb out of the pair is more common than the intransitive one.

Note;- The way you say "allow" or "let" in béu is to use the gambe along with the hái "give".

I let her go => hari liʔa oye

.

-pi or pì : pilana naja ... (the first pilana)

meu (rà) "basket"pi

While the original meaning was about space, this pilana is very often found referring to time.

I read the book hourpi => I read the book in an hour

I gets dark pi ten minutes => It get dark in ten minutes

She qualified as a doctor pi five years

One can get from Glasgow to London daypi

I'm coming to Sweden pi next month

meu (rà) topla basketn = The cat is on top of the house

meu (rà) interior basketn = the cat is in the basket

-la or lá : pilana nauva ... (the second pilana)

mat (rà) floorla => the mat is on the floor ... notice "the mat"

ʔá mat floorla => there is a mat on the floor ... notice "a mat"

meu (rà) top.la nambo.n => The cat is on top of the house

ʔaya "money" nà pà => I don't have any money ... notice that "money" is indefinite ...

Do I need the three copula's ? ... how quickly would they collapse to two or one ?

-ye or yè : pilana naiba ... (the third pilana)

xxx yyy oye = give the book to her

xxx yyy paye = tell me about it

This is the pilana used for marking the receiver of a gift, or the receiver of some knowledge.

However the basic usage of the word is directional.

*namboye => nambye = "to the house"

.

ye "distance" nà nambo = "as far as the house"

ye "limit" nà nambo = "up to the house" ... this usage is not for approaching humans however ... for that you must use "face".i.e. ye "face" nà báu = right up to the man

.

"direction" nà nambo = towards the house i.e. you don't know if this is his destination but he is going in that direction

yèu = to arrive ... yài a SVC meaning "to start" ... fái a SVC meaning "to stop" ???

-vi or fí : pilana nuga ... (the fourth pilana)

nambovi = "from the house"

fí "direction" nà nambo = "away from the house" i.e.you don't know if this is his origin but he is coming from the direction that the house is in.

fí "limit/border" nà nambo = all the way from the house

fí "top" nà nambo = from the top of the house ... and so on for "bottom", "front", etc. etc.

he changed frog.vi ye prince handsome = he changed from a frog to a handsome prince

fía = to leave, to depart ... fái a SVC meaning "to finish" .... then bai cound mean continue and -ana would be the present tense ???

-lya or alya : pilana nida ... (the fifth pilana)

Sometimes called the "Allative case" but we don't have to worry about that rubbish here. Can be said to translate to English as "onto".

xxx yyy zzz = put the cushions on the sofa

-lfe or alfe : pilana nela ... (the sixth pilana)

Sometimes called the "Ablative case" but we don't have to worry about that rubbish here.

-s or sá : pilana noica ... (the seventh pilana)

that Stefen turned up drunk at the interview sank his chance of getting that job

swe ta ........

-ʔe or ʔé : pilana neza ... (the eighth pilana)

ò (rà) namboʔe = He is at home

Notice that there are to ways to say "He is at home" ... or at anywhere (could there be some grammatic distinction between them ??)

In a similar manner when a destination comes immediately after the verb loʔa "to go" the pilana -ye is always dropped.

In a similar manner when a origin comes immediately after the verb kome "to come" the pilana -vi is always dropped.

(Hold on I have to think about the above two ... not symmetrical, what about Thai)

CENʔO ...... marking person and number on a verb

The main verb form (the r-form)

Now we take a typical verb to demonstrate the béu verb system. doika meaning "to walk" or "the act of walking" will do.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In English the form of a verb which we use when we are talking about that verb, is called the "infinitive". The English infinitive seems to function pretty much like a noun, though it retains some verb-like characteristics. In béu the form used (the recitation form) when we talk about a verb, is called geladi. It is fully a noun. For example kalme would be translated as "demolition" rather than "to demolish".

cen@o = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play ... it is also the word used, for the vowel that is inserted immediately before the r in the r-form verb.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she) and number refers to how the person changes when in the plural (sometimes dual also)

doikari = I walked

doikiri = You walked

doikori = He/She/It walked

doikuri = They walked

doikeri = You walked (this form is used when talking to more than one person)

doikauri = We walked (this form is used when the person spoken to, is not included in the "we")

doikairi = We walked (this form is used when the person spoken to, is included in the "we")

Note that the last form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

GWOMA .. marking tense and aspect on a verb

gwoma is a verb meaning "to modify", "to alter", "to change one attribute of something'". It is a verbal noun so gwoma also means "modification".

gwomai (modifications) has a special meaning in béu linguistics ... namely the nine suffixes which give tense and aspect information.

Here are the gwomai in the order that they are traditionally given.

1) doikari = I walked

This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

2) doikarta = I have walked

While logically this doesn't have much difference from 1), it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

3) doikarti = I had walked

This is similar to 2) except the time of relevance has shifted to the past. For example in a narrative if you wanted to explain the state of John at the party last night, you would say "When I met John, he had drunk eight cans of beer".

4) doikartu = I will have walked

This is similar to 3) except the time of relevance has shifted to the future.

5) doikaru = I will walk

This is the future tense. Of course you can never be 100% sure of the future. But (as in English) the future is dealt with in a similar way to the past.

6) doikara = I walk

In English "I walk" is usually called the "present tense" however this is a bit unfortunate. In English, "I am walking" is really the present tense and "I walk" shows habitualness (in the past, present and future). For example "I walk to school". Also in English this form is used to expresses timeless truths ... for example "birds fly". (You could say this is the "default" tense/aspect form in English)

In béu the ara form is used to express timeless truths also (You could say this is the "default" gwomai in béu). However to show habitualness, béu uses form 9), the rwa tense. For example ;-

diabuye doikarwa = I walk to school ... Well actually béu has the rwa tense, but often the ra tense is used instead. For example you would never use diabuye doikarwa unless you were going to mention an exception (for example ... "but last Tuesday my Uncle drove me in his car")

7) doikarwi = I used to walk

doikarwi shows that you had many instances of walking in the past. For example "When I was a young girl, I used to walk 5 miles to school"

8) doikarwu = I will walk, I will be walking

9) doikarwa = I usually walk

Note that in translating "I walk" from English into béu, you have a choice of doikarwa or doikara. Generally the doikarwa form should be used if your possible walking time is interspersed with periods of non-walking. donarwa could be translated as "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk".

There is no exact equivalent to this on in English. Often confused with doikaru ( 5) ). Basically if the act of walking is just a one off ... for example in answer to the question "how are you going to the supermarket", doikaru would be used. But suppose that you had just moved to a new house, then the question "how will you get to the supermarket" is envisioning many instances of "walking" ... in that case, doikarwu would be used.

The above is an example of a "nuance" missing from English that béu has. Below I give an example of a "nuance" that English has but which béu lacks.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out". The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" to build up muscles.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

(In béu the muscle-bound schoolmate would probable use the "-rwa" form of the verb ; along with an particle meaning "now")

Note ... if you say "I walk to church every Sunday" you have a choice of...

A) using doikarwa and dropping the béu equivalent to "every".

B) using doikara and using the béu equivalent to "every".

With (A) implying that you ONLY go on Sunday, whereas (2) leaves open the possibility that you go on other days of as well.

These suffixes are given in the chart below. The béu terms for the different rows and columns are given. In the Western Linguistic tradition we would have ;-

Time => tense Behind => past Middle => present (although most people agree this is an unfortunate term) Ahead => future Aspect => aspect Completed => perfect Customary => habitual

TENKO ..... marking evidentiality on a verb

tenkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate".

tenko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. (It is unknown in Europe so most people have never heard of it) In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In béu there are 3 evidential affixes which can optionally be added to the verb.

doikori = He walked ... this is the neutral verb. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is stating "he walked".

doikorin = They say he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow. (Maybe in this case he had seen that the "he" had muddy boots, and so later told a third person "he walked".

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The third tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself". This tenko can only be used with the "i" gwoma

7 cen@o (protagonist) which are obligatory.

9 gwoma (modifiers) which are obligatory.

3 tenko (proofs) which are optional.

The Calendar

The béu calendar is interesting. Definitely interesting. A 73 day period is called a dói. 5 x 73 => 365.

The phases of the moon are totally ignored in the béu system of keeping count of the time.

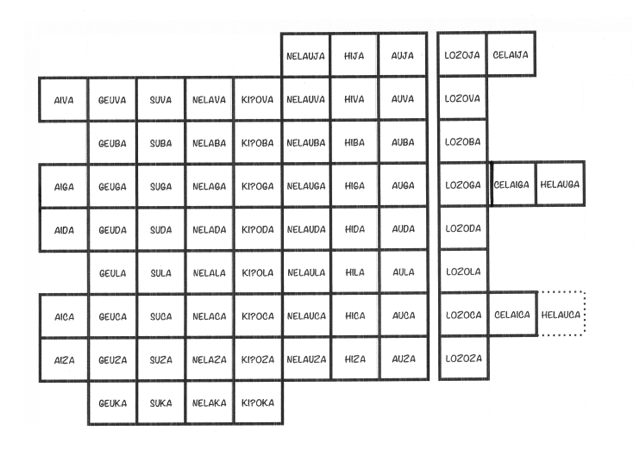

The first day of the dói is nelauja followed by hija, then auja lozoja celaija and then aiva etc. etc. all the way upto kiʔoka.

The days to the right are workdays (saipito) while the days to the left are days off work (saifuje). Each month has a special festival (hinta) associated with it. These festivals are held in the three day period comprising lozoga, celaiga, helauga. The five "months" are named after the 5 planets that are visible to the naked eye. The 5 big festivals that occur every year are also named after these planets.

| mercury | ʔoli | Month 1 | doiʔoli | Xmas... on 21,22,23 Dec | hinʔoli |

| venus | pwè | Month 2 | doipwe | festival on 4,5,6 Mar | himpwe |

| mars | gú | Month 3 | doigu | festival on 16,17,18 May | hiŋgu |

| jupiter | gamazu | Month 4 | doigamazu | festival on 28,29,30 July | hiŋgamazu |

| saturn | yika | Month 5 | doiyika | festival on 9,10,11 Oct | hinyika |

hinʔoli ... This is the most important festival of the year. It celebrates the starting of a fresh year. It celebrates the stop of the sun getting weaker. It is centred on the family and friends that you are living amongst. Even though eating and drinking are involved in all the five festivals, this festival has the most looked-forward-to feasts.

himpwe ... People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various music and poetry competitions. Sky lanterns are usually released on the last day of this festival. On the first two days of the festival, what is called the "fire walk" is performed. This is to promote social solidarity. Each locality comprising up to 400 people build a fire in some open ground. These people are divided into 2 sections. One section to walk and one section to receive walkers. The walkers are further divided into groups. Each group is assigned another fire to visit and they set of in single file. Each of them carries a torch (a brand) ignited from the home fire. Upon arriving at the fire that they have been assigned (involving a walk of, maybe, 5 or 6 miles) they throw their brand into the fire as their hosts sing the "fire song". After that the visitors are offered much drinks and snacks by their hosts. There is considerable competition between the various localities to be the most generous host. The routes that people must go have been chosen previously by a central committee, but the destination is only revealed to the walkers just before they set out. On the second day the same thing happens but the two sections, the walkers and the receivers of the walkers, swap over rolls.

hiŋgu ... It is usual to get together with old friends around this time and many parties are held. Friends that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken to meet up with old acquainances. Also there is a big exchange of letters at this time. The most important happenings of the last year are stated in these letters along with hopes and plans for the coming year.

hiŋgamazu ... This festival is all about outdoor competitions and sporting events. It is a little like a cross between the Olympics games and the highland games. People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various team and individual competitions. However care is taken that no regional centre becomes too popular and people are discouraged from competing at centres other than their local one. Also at this festival, a "fire walk" is done, just the same as at the "himpwe" festival.

hinyika ... Family that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken for family visits and ancestors ashboxes are visited if convenient. This is the second most important festival of the year. People often take extra time off work to travel, or to entertain guests. Fireworks are let of for a 2 hour period on the night of helauga. This is one of the few occasions where fireworks are allowed.

By the way, when a year changes, it doesn't change between months, it changes between lozoga and celaiga.

Every 4 years an extra day is added to the year. The doiʔoli gets a helauca.

béu also has a 128 year cycle. This circle is called ombatoze. There is a animal associated with every year of the ombatoze.

These animals are ;-

| wolf | weasel/ermine/stoat/mink | bullfinch | badger |

| whale | opossum | albatross | beautiful armadillo |

| giant anteater | lynx | eagle | cricket/grasshopper/locust |

| reindeer | springbok | dove | gnu/wildebeest |

| spider | Steller's sea cow | seagull | gorilla |

| horse | scorpion | raven/crow | python |

| rhino | yak | Kookaburra | porcupine ? |

| butterfly | triceratops | penguin | koala |

| polar bear | manta-ray | hornbill | raccoon |

| crocodile/alligator | wolverine | pelican | zebra |

| bee | warthog | peacock | capybara |

| bat | bear | crane/stork/heron | hedgehog |

| frog | lama | woodpecker | gemsbok |

| musk ox | chameleon | hawk | cheetah |

| lion | frill-necked lizard | toucan | okapi |

| dolphin | aardvark | ostrich | T-rex |

| kangaroo | hyena | duck | driprotodon(wombat) |

| shark | cobra | kingfisher | gaur |

| dragonfly | mole | moa | chimpanzee |

| turtle/tortoise | N.A. bison | black skimmer | panda |

| jaguar | snail | cormorant/shag | Cape buffalo |

| rabbit | colossal squid | vulture | glyptodon/doedicurus |

| beetle | seal | falcon | pangolin |

| megatherium | woolly mammoth | flamingo | baboon |

| elk/moose | squirrel | blue bird of paradise | lobster |

| tiger | gecko | grouse | seahorse |

| jackal/fox | octopus | swan | lemur |

| elephant | swordfish | parrot | auroch |

| giraffe | ant | puffin | iguana |

| mouse | crab | swift | mongoose/meerkat |

| smilodon | giant beaver | owl | mantis |

| camel | goat | hummingbird | walrus |

Each of these animals above is a toze, which can be translated as "token", "icon" or "totem ". omba means a circle or cycle. So you can see where the name for the 128 year period comes from.

The very last helauca of every ombatoze is dropped.

ombatoze is sometimes translated as "life", "generation" or "century"

xxx means a 4 year period. It also means "calendar".

Star time

Year 2000 had 365.242,192,65 days

Every year is shorter than the last by 0.000,000,061,4 days

By adding one day every 4 years we get a 365.25 day year

If we then drop one day every ombatoze we get a 365.242,187,5 day year (actually very close to the actual year length)

Before 2084, the actual year will be bigger than the calendar year – after 2084 the actual year will be smaller than the calendar year

For this reason midnight, 22 Dec 2083 is designated the fulcrum of the whole system. That day will be time zero.

At the moment we are in negative time.

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences