Béu : Chapter 3

-vi or fí : pilana nuga ... (the fourth pilana)

nambovi = "from the house"

fí "direction" nà nambo = "away from the house" i.e.you don't know if this is his origin but he is coming from the direction that the house is in.

fí "limit/border" nà nambo = all the way from the house

fí "top" nà nambo = from the top of the house ... and so on for "bottom", "front", etc. etc.

he changed frog.vi ye prince handsome = he changed from a frog to a handsome prince

fía = to leave, to depart ... fái a SVC meaning "to finish" .... then bai cound mean continue and -ana would be the present tense ???

-lya or alya : pilana nida ... (the fifth pilana)

Sometimes called the "Allative case" but we don't have to worry about that rubbish here. Can be said to translate to English as "onto".

xxx yyy zzz = put the cushions on the sofa

-lfe or alfe : pilana nela ... (the sixth pilana)

Sometimes called the "Ablative case" but we don't have to worry about that rubbish here.

-s or sá : pilana noica ... (the seventh pilana)

that Stefen turned up drunk at the interview sank his chance of getting that job

swe ta ........

-ʔe or ʔé : pilana neza ... (the eighth pilana)

ò (rà) namboʔe = He is at home

Notice that there are to ways to say "He is at home" ... or at anywhere (could there be some grammatic distinction between them ??)

In a similar manner when a destination comes immediately after the verb loʔa "to go" the pilana -ye is always dropped.

In a similar manner when a origin comes immediately after the verb kome "to come" the pilana -vi is always dropped.

(Hold on I have to think about the above two ... not symmetrical, what about Thai)

CENʔO ...... marking person and number on a verb

The main verb form (the r-form)

Now we take a typical verb to demonstrate the béu verb system. doika meaning "to walk" or "the act of walking" will do.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In English the form of a verb which we use when we are talking about that verb, is called the "infinitive". The English infinitive seems to function pretty much like a noun, though it retains some verb-like characteristics. In béu the form used (the recitation form) when we talk about a verb, is called gamba (meaning source or origin). It is fully a noun. For example kalme would be translated as "demolition" rather than "to demolish".

cen@o = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play ... it is also the word used, for the vowel that is inserted immediately before the r in the r-form verb.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she) and number refers to how the person changes when in the plural (sometimes dual also)

doikari = I walked

doikiri = You walked

doikori = He/She/It walked

doikuri = They walked

doikeri = You walked (this form is used when talking to more than one person)

doikauri = We walked (this form is used when the person spoken to, is not included in the "we")

doikairi = We walked (this form is used when the person spoken to, is included in the "we")

Note that the last form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

GWOMA .. marking tense and aspect on a verb

gwoma is a verb meaning "to modify", "to alter", "to change one attribute of something'". It is a verbal noun so gwoma also means "modification".

gwomai (modifications) has a special meaning in béu linguistics ... namely the nine suffixes which give tense and aspect information.

Here are the gwomai in the order that they are traditionally given.

1) doikari = I walked

This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

2) doikarta = I have walked

While logically this doesn't have much difference from 1), it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

3) doikarti = I had walked

This is similar to 2) except the time of relevance has shifted to the past. For example in a narrative if you wanted to explain the state of John at the party last night, you would say "When I met John, he had drunk eight cans of beer".

4) doikartu = I will have walked

This is similar to 3) except the time of relevance has shifted to the future.

5) doikaru = I will walk

This is the future tense. Of course you can never be 100% sure of the future. But (as in English) the future is dealt with in a similar way to the past.

6) doikara = I walk

In English "I walk" is usually called the "present tense" however this is a bit unfortunate. In English, "I am walking" is really the present tense and "I walk" shows habitualness (in the past, present and future). For example "I walk to school". Also in English this form is used to expresses timeless truths ... for example "birds fly". (You could say this is the "default" tense/aspect form in English)

In béu the ara form is used to express timeless truths also (You could say this is the "default" gwomai in béu). However to show habitualness, béu uses form 9), the rwa tense. For example ;-

diabuye doikarwa = I walk to school ... Well actually béu has the rwa tense, but often the ra tense is used instead. For example you would never use diabuye doikarwa unless you were going to mention an exception (for example ... "but last Tuesday my Uncle drove me in his car")

7) doikarwi = I used to walk

doikarwi shows that you had many instances of walking in the past. For example "When I was a young girl, I used to walk 5 miles to school"

8) doikarwu = I will walk, I will be walking

9) doikarwa = I usually walk

Note that in translating "I walk" from English into béu, you have a choice of doikarwa or doikara. Generally the doikarwa form should be used if your possible walking time is interspersed with periods of non-walking. donarwa could be translated as "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk".

There is no exact equivalent to this on in English. Often confused with doikaru ( 5) ). Basically if the act of walking is just a one off ... for example in answer to the question "how are you going to the supermarket", doikaru would be used. But suppose that you had just moved to a new house, then the question "how will you get to the supermarket" is envisioning many instances of "walking" ... in that case, doikarwu would be used.

The above is an example of a "nuance" missing from English that béu has. Below I give an example of a "nuance" that English has but which béu lacks.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out". The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" to build up muscles.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

(In béu the muscle-bound schoolmate would probable use the "-rwa" form of the verb ; along with an adverb meaning "now")

Note ... if you say "I walk to church every Sunday" you have a choice of...

A) using doikarwa and dropping the béu equivalent to "every".

B) using doikara and using the béu equivalent to "every".

With (A) implying that you ONLY go on Sunday, whereas (2) leaves open the possibility that you go on other days of as well.

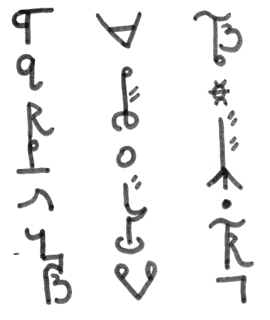

These suffixes are given in the chart below. The béu terms for the different rows and columns are given. In the Western Linguistic tradition we would have ;-

Time => tense Behind => past Middle => present (although most people agree this is an unfortunate term) Ahead => future Aspect => aspect Completed => perfect Customary => habitual

TENKO ..... marking evidentiality on a verb

tenkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate".

tenko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. (It is unknown in Europe so most people have never heard of it) In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In béu there are 3 evidential affixes which can optionally be added to the verb.

doikori = He walked ... this is the neutral verb. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is stating "he walked".

doikorin = They say he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow. (Maybe in this case he had seen that the "he" had muddy boots, and so later told a third person "he walked".

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The third tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself". This tenko can only be used with the "i" gwoma

7 cen@o (protagonist) which are obligatory.

9 gwoma (modifiers) which are obligatory.

3 tenko (proofs) which are optional.

NOIGA ..... arithmetic

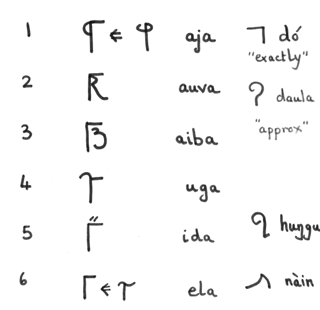

Above right you can see the numbers 1 -> 11 displayed. Notice that the forms of 1, 3, 6, 7 and 9 have been modified slightly before the "number bar" has been added.

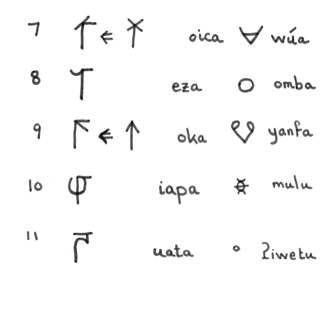

In the bottom right you can see 7 interesting symbols. These are used to extend the range of the béu number system (remember the basic system only covers 1-> 1727). Their meanings are given in the table below.

| elephant | huŋgu |

| rhino | nàin |

| water buffalo | wúa |

| circle | omba |

| hare | yanfa |

| beetle | mulu |

| bacterium, bug | ʔiwetu |

To give you an idea of how they are used, I have given you a very big number below.

Which is => 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... E represents eleven and T represents ten ... remember the number is in base 12.

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only: if you can handle this number you can handle any number.

This monster would be pronounced aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dó

Now the 7 "placeholders" are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. The béu community has a very strong feeling that there are only 1727 proper numbers. You never see (the béu equivalent of) "a thousand" or "a million". Rather you would hear "ONE thousand exactly", or "ONE thousand approximately". (Actually I tell a lie, there are a number of sayings, where you can hear "ONE thousand" etc. etc.)

When first introduced to this system, many people think that the béu culture must be untenable, however strangely enough the béu culture has lasted many thousands of year, despite the obvious confusion that must arise when they attempt to count elephants.

One further point ...

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say auvaidaula nàin .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say yanfa elaibau .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630" instead of "630 micro".

Ah that is another thing ... the units used either come at the end (or they can replace omba (which means "unit" as well as "circle", by the way)). Our SI system uses magnitude words which are prefixed to the unit of measurement (for example "kilo" in kilometre). béu also has magnitude words (the seven already given) but they are inserted into the number itself. It is a bit similar to the way we use comma's to separate a long number string into groups of three digits.

To make a number negative the "number bar" is placed on the left. See below ;-

Also a number can be made imaginary by adding a further stroke that touches the "number bar". See below ;-

As you can see above, there is no special sign for the "addition operation". The numbers are simply written one beneath the other. Similarly with subtraction but one number would be negative this time.

There is a special sign to indicate multiplication (+), and there is an equals sign (-).

Division is the same as multiplication except that one of the numbers is in "fractional form".

There is an alternative multiplication/division notation : instead of using the + sign, the two quantities can instead be written side by side (see the example above).

-6 is pronounced ù ?? ela ... ela "negative"

4i is pronounced aspo ?? uga ... uga "imaginary"

-4i is pronounced ù aspo ?? uga ... uga "imaginary negative" or uga "negative imaginary", it doesn't really matter.

-1/10 is pronounced diapa "negative"

i/4 is pronounced duga "imaginary"

SAINO ...... the time of day

saino = day

The béu day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called cuaju

The time of day is counted from cuaju. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called ajai (normally just called ajai, but cúa ajai or ajai yanfa might also be heard sometimes).

| 6 o'clock in the morning | cuaju |

| 8 o'clock in the morning | ajai |

| 10 o'clock in the morning | uvai |

| midday | ibai |

| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | agai |

| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | idai |

| 6 o'clock in the evening | ulai |

| 8 o'clock in the evening | icai |

| 10 o'clock at night | ezai |

| midnight | okai |

| 2 o'clock in the morning | apai |

| 4 o'clock in the morning | atai |

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon.

16:00 would be idai : 16:10 would be idaijau : 16:20 would be idaivau .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be idaitau

Now all these names have in common the element idai, hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called idaia (the plural of idai). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties".

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called cuajua. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time ajai was called ajaia(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time cuaju should be called cuajua. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial cuaju. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be cuaju ajau, "twenty past six" would be cuaju avau and so on.

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened idaia.pi

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them apaiʔe.

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued nàn uvau, for 2 hours : nàn ajai (nàn means "a long time")

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In béu they only have the yanfa. The yanfa is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as yanfa also.

The town clock

Every town has a clocktower and the clocktower has 4 faces, which are aligned with the cardinal directions. The street pattern is also so aligned : that is the four biggest streets radiate out from the clock in the cardinal directions.

Each face displaying a clock similar to the one below.

The above figure shows the time at exactly 6 in the morning. You notice that the main (hour hand) hand is pointing to the right : it starts from the horizontal. This hand sweeps out one revolution in 24 hours and it moves anti-clockwise

Notice that secondary (minute hand) starts from the vertical and sweeps out a revolution in 2 of our hours. It moves clockwise. And actually when it passes the main hand, there is a clever mechanism to stop it being hidden. It stops 3.75 minutes at one side of the main hand, and then moves directly (2 steps) to the other side of the main hand and stops there for 3.75 minutes. After that it does a step and waits 2.5 minutes, etc. etc. ... until it encounters the main hand again.

We are actually looking at the West face. Everything is black which is shown black above. However the secondary hand and the 36 small "diamonds" should be red. All else (inside and outside the main "band") is white for this face. The red and the black arms do not move continuously but move in steps of 1/48 th of a revolution at a time. The black arm moves every 30 minutes and the red arm moves every 2.5 minutes.

For the East face: red => silver : white => green : black as before

For the North face: red => light blue : white => orange : black as before

For the South face: red => dark blue : white => red : black as before

The clocktower is surmounted by a green conic roof (actually not really conic ... the roof slope decreases as you get nearer the bottom). Lighting from under the roof could be provided for each face. Either that or the faces could be illuminated from within at night. The faces are not exactly vertical but the top slightly overhangs the bottom.

There is never any numbering on the face.

The clock also emits sounds. Every 2 of our hours the clock makes a deep "boing" which reverberates for some time. Also from 6 in the morning to 6 at night, the clock emits a "boing" every 30 of our minutes. The first "boing" has no accompaniment. However the second "boing" is followed (well actually when the "boing" is only .67 % dissipated) by a "sharper" sound that dies down a lot quicker : "teen". The third "boing" has 2 "teen"s 0.72 seconds apart. The fourth has 3 "teen"s. The fifth one is back to the single "boing" and so it continues thru the day.

The Calendar

The béu calendar is interesting. Definitely interesting. A 73 day period is called a dói. 5 x 73 => 365.

The phases of the moon are totally ignored in the béu system of keeping count of the time.

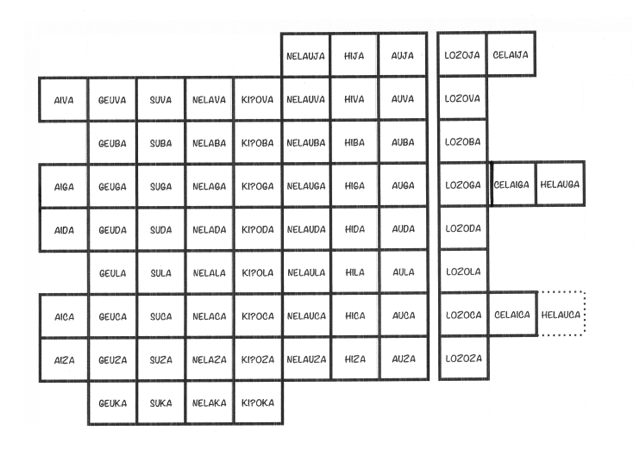

The first day of the dói is nelauja followed by hija, then auja lozoja celaija and then aiva etc. etc. all the way upto kiʔoka.

The days to the right are workdays (saipito) while the days to the left are days off work (saifuje). Each month has a special festival (hinta) associated with it. These festivals are held in the three day period comprising lozoga, celaiga, helauga. The five "months" are named after the 5 planets that are visible to the naked eye. The 5 big festivals that occur every year are also named after these planets.

| mercury | ʔoli | Month 1 | doiʔoli | Xmas... on 21,22,23 Dec | hinʔoli |

| venus | pwè | Month 2 | doipwe | festival on 4,5,6 Mar | himpwe |

| mars | gú | Month 3 | doigu | festival on 16,17,18 May | hiŋgu |

| jupiter | gamazu | Month 4 | doigamazu | festival on 28,29,30 July | hiŋgamazu |

| saturn | yika | Month 5 | doiyika | festival on 9,10,11 Oct | hinyika |

hinʔoli ... This is the most important festival of the year. It celebrates the starting of a fresh year. It celebrates the stop of the sun getting weaker. It is centred on the family and friends that you are living amongst. Even though eating and drinking are involved in all the five festivals, this festival has the most looked-forward-to feasts.

himpwe ... People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various music and poetry competitions. Sky lanterns are usually released on the last day of this festival.

hiŋgu ... It is usual to get together with old friends around this time and many parties are held. Friends that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken to meet up with old acquainances. Also there is a big exchange of letters at this time. The most important happenings of the last year are stated in these letters along with hopes and plans for the coming year.

hiŋgamazu ... This festival is all about outdoor competitions and sporting events. It is a little like a cross between the Olympics games and the highland games. People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various team and individual competitions. However care is taken that no regional centre becomes too popular and people are discouraged from competing at centres other than their local one.

hinyika ... Family that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken for family visits and ancestors ashboxes are visited if convenient. This is the second most important festival of the year. People often take extra time off work to travel, or to entertain guests. Fireworks are let of for a 2 hour period on the night of helauga. This is one of the few occasions where fireworks are allowed.

By the way, when a year changes, it doesn't change between months, it changes between lozoga and celaiga.

Every 4 years an extra day is added to the year. The doiʔoli gets a helauca.

béu also has a 128 year cycle. This circle is called ombatoze. There is a animal associated with every year of the ombatoze.

These animals are ;-

| wolf | weasel/ermine/stoat/mink | bullfinch | badger |

| whale | opossum | albatross | beautiful armadillo |

| giant anteater | lynx | eagle | cricket/grasshopper/locust |

| reindeer | springbok | dove | gnu/wildebeest |

| spider | Steller's sea cow | seagull | gorilla |

| horse | scorpion | raven/crow | python |

| rhino | yak | Kookaburra | porcupine ? |

| butterfly | triceratops | penguin | koala |

| polar bear | manta-ray | hornbill | raccoon |

| crocodile/alligator | wolverine | pelican | zebra |

| bee | warthog | peacock | capybara |

| bat | bear | crane/stork/heron | hedgehog |

| frog | lama | woodpecker | gemsbok |

| musk ox | chameleon | hawk | cheetah |

| lion | frill-necked lizard | toucan | okapi |

| dolphin | aardvark | ostrich | T-rex |

| kangaroo | hyena | duck | driprotodon(wombat) |

| shark | cobra | kingfisher | gaur |

| dragonfly | mole | moa | chimpanzee |

| turtle/tortoise | N.A. bison | black skimmer | panda |

| jaguar | snail | cormorant/shag | Cape buffalo |

| rabbit | colossal squid | vulture | glyptodon/doedicurus |

| beetle | seal | falcon | pangolin |

| megatherium | woolly mammoth | flamingo | baboon |

| elk/moose | squirrel | blue bird of paradise | lobster |

| tiger | gecko | grouse | seahorse |

| jackal/fox | octopus | swan | lemur |

| elephant | swordfish | parrot | auroch |

| giraffe | ant | puffin | iguana |

| mouse | crab | swift | mongoose/meerkat |

| smilodon | giant beaver | owl | mantis |

| camel | goat | hummingbird | walrus |

Each of these animals above is a toze, which can be translated as "token", "icon" or "totem ". omba means a circle or cycle. So you can see where the name for the 128 year period comes from.

The very last helauca of every ombatoze is dropped.

ombatoze is sometimes translated as "life", "generation" or "century"

xxx means a 4 year period. It also means "calendar".

Star time

Year 2000 had 365.242,192,65 days

Every year is shorter than the last by 0.000,000,061,4 days

By adding one day every 4 years we get a 365.25 day year

If we then drop one day every ombatoze we get a 365.242,187,5 day year (actually very close to the actual year length)

Before 2084, the actual year will be bigger than the calendar year – after 2084 the actual year will be smaller than the calendar year

For this reason midnight, 22 Dec 2083 is designated the fulcrum of the whole system. That day will be time zero.

At the moment we are in negative time.

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences