Piscean language

Piscean (Piscean: pisceesum) is the official language of the New Piscean Workers' Nation, founded on the manmade island New Pisces - off the coast of western France - that was created in 2028. Despite being the constructed language of Representative S.C. Anderson, Piscean is linguistically derived from Old English and Modern German; however, it is written not with the Latin or runic alphabets, but with the 'pro-Phoenician' Andersonic writing system devised in 2007. (For the purpose of this article, examples of Piscean will be transliterated into the Latin alphabet.)

Articles

The Piscean language includes three 'logical' grammatical genders. While in many languages, the genders do not often relate to physical properties of nouns, they do in Piscean; therefore, most nouns are neuter, while creatures of the male sex are masculine and creatures of female sex are feminine. If one refers to a creature, but does not wish to distinguish sex, the neuter gender can be used as a substitute. Observe the following examples:

- teet Sunne - the sun (no sex, so neuter)

- teet Mann - the person (no sex specified, so neuter)

- se Mann - the man (male, so masculine)

- seo Mann - the woman (female, so feminine)

The above example shows the importance the article plays in Piscean of distinguishing between sexes in a language where one noun fits all.

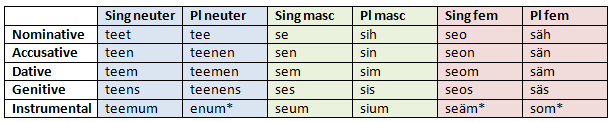

Definite article

The definite article is inflected in various ways, firstly split into three depending on grammatical gender, then into six depending also on quantity - whether singular or plural - and finally into a further thirty depending on grammatical case - whether nominative, accusative, dative, genitive or instrumental.

Those words highlighted with an asterisk follow irregular patterns. 'Enum' is a contraction arising from a rather complex - and now incorrect - 'teemenum'. 'Seäm' is a result of 'seoum', which is difficult for a Piscean speaker to pronounce. The O and U thus collapse into Ä. Similarly, 'som' is contrived, as 'säum' is awkward in speech, giving way instead to a collapse of Ä and U into O.

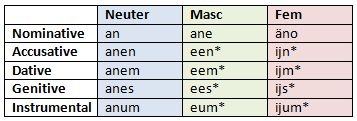

Indefinite article

The indefinite article (in English, 'a/an') is inflected in much the same way as the definite article, but lacking plural forms (which are shown not with an article, merely by inflecting the noun itself).

Those words highlighted with an asterisk follow irregular patterns. 'Een', 'eem', 'ees' and 'eum' are contracted forms of 'aneen', 'aneem', 'anees' and 'aneum', respectively. Regarding the feminine irregularities, 'änoen', 'änoem', 'änoes' and 'änoum' first contracted to 'oen', 'oem', 'oes' and 'oum', but - for even easier pronunciation - the O (and E, where applicable) finally collapsed into the dipthong IJ, which sounds like the English word 'eye'.

Cases and prepositions

Piscean implements five cases: nominative, accusative, dative, genitive and instrumental. Anderson affirms that these have greatly important and stylistic purposes.

Nominative

This case is used for the subject of the sentence (i.e. the noun doing the verb) and as a complement after: 'bean' ('to be'), 'weortan' ('to become') and 'hatan' ('to be called').

Accusative

This case is used for the direct object (i.e. the noun having the verb done to it/them) and after certain prepositions:

- to (for)

- ijmbe (around)

- geond (through)

- ot (until)

- butan (without)

- wider (contrary to)

- on (against)

- betwix (among)

- tonne (than)

- ofer (during)

- abreotan (failing)

- folgian (following)

- gelice (like)

- minus (minus)

- nahtmidstandan (notwithstanding)

- plus (plus)

- belimpan (regarding)

- geondut (throughout)

- mal (times)

- togänes (towards)

- ungelice (unlike)

- fortonan (because of)

- tonteetan (in order that)

- leesan (in case of)

- interessan (on behalf of)

The accusative case allows for flexible sentence structure that can place emphasis on a certain word by changing its location, yet retaining original meaning. For example:

- Se Hund bit sen Mann - The dog bites the man

- Sen Mann bit se Hund - The dog bites the man

Both of the above Piscean sentences have the same translation into English. On first glance, an English speaker might confuse the second example as 'the man bites the dog', although this is because the object comes before the subject. Because the word 'Mann' is preceded by the accusative article and 'Hund', by the nominative, those skilled in Piscean can easily deduce the sentence's meaning. Meanwhile, the first example places emphasis on the subject, while the second places greater emphasis on the object.

Dative

This case is used for the indirect object (i.e. the noun receiving or being given/sent/lent something); note that in this usage, there is no requirement to translate the word 'to' from English to Piscean:

- Icc geef hit sem Leerere - I give it (to) the teacher

The 'to' is not translated because it is suggested by the dative case ('sem').

When one goes to a place, that place is technically 'receiving' one, so the dative case is used when referring to travel. For example:

- Icc far teem Larenhus - I go to the school; I go to school

Note that proper nouns (that don't take an article) can also be inflected to reflect case:

- Lundenburg - London (nominative)

- Lundenburgen - London (accusative)

- Lundenburgem - London (dative)

- Lundenburges - London (genitive)

- Lundenburgum - London (instrumental)

The action of going to London would involve the dative case:

- Icc far Lundenburgem - I go to London

It is also used after certain prepositions:

- eet (at)

- ut (outside)

- fram (from)

- ofer (about)

- eefter (after/according to)

- ongän (opposite)

- sittan (since)

- butan (except)

- mid (with)

- behionan (alongside)

- rittlingan (astride)

- beforan (before)

- gehende (near)

- edzan (aslant [into])

Genitive

This case is used to denote possession or ownership. 'The man's car' translates literally as 'the car of the man', but without any word for 'of'.

- Teet Wagen ses Mann - the man's car (the car of the man)

To put proper nouns into the genitive case: if the noun ends in a consonant, add 'es'; if the nound ends in a vowel or Y, add 's'. For example:

- Teet Rum Seanes - Sean's room (the room of Sean)

- Teet Deejweorc Gaynores - Gaynor's job (the job of Gaynor)

Instrumental

The first use of the instrumental case is to replace words such as 'with' and 'by' in English in the context that they mean 'by means of' - in other words, to indicate that the noun in question is an 'instrument'. Usually, the instrumental case is not used with an article, unless for emphasis; therefore, the noun itself must be inflected. Despite the rule in Piscean that all nouns begin with a capital letter, when in the instrumental case, this capital is dropped. If a noun ends in a consonant, one must add 'um' to make it instrumental; if a noun ends in a vowel, one must add 'num'.

- Teet Bän - the train

- Icc far bänum - I go (by) train

- Teet Culi - the pen

- Icc writ culinum - I write (with a) pen

The second use of the instrumental case is to denote belonging, belief or status. When the noun is inflected, it can become similar to an adjective:

- Englaland - England

- Icc bee englalandum - I am English

- Icc sprec englalandum - I speak English

- Commjunizmäs - communism

- Icc bee commjunizmäsum - I am communist

Irregular prepositions

The third group of prepositions are designated no specific case. They are followed by accusative if they describe where something/things travel or dative if they describe where something/things already is/are. For example:

- Icc far in teen Rum - I go into [the room] (accusative)

- Icc bee in teem Rum - I am in [the room] (dative)

The following prepositions are applied in this manner:

- in (in/into)

- behindan (behind)

- bufan (on top of)

- eetforan (in front of)

- bee (on, e.g. the wall; along)

- oter (next to)

- ofer (over/above; across)

- betweonan (between)

- under (under)

- needrigan (below)

- begeondan (beyond)

- dun (down)

- up (up/upon)

- hinter (past)

- bordan (aboard)

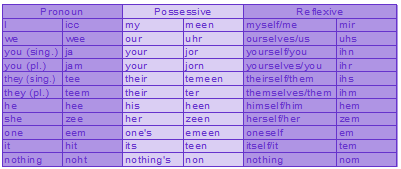

Pronouns

Pronouns in Piscean bear little resemblance to those in either Old English or German. This is because Anderson, Editor of the Piscean Lexicon, deemed their pronouns 'incompatible with the style and rules of the language'. Therefore, a new set of pronouns has been contrived, each with three inflections: pronoun, possessive and reflexive. (Note that, in Piscean, when the reflexive pronoun is referred to, it can be either reflexive or objective: in Piscean, both are the same.)

Below are demonstrations of how the different forms are used:

- Icc bee an Lingwist - I am a linguist (pronoun)

- Meen Boc - My book (possessive pronoun)

- Icc feorme mir - I wash myself (pronoun and reflexive pronoun)

- Frignan naht mir - Don't ask me (reflexive [objective] pronoun)

To say words such as 'mine', 'yours' and 'theirs' in Piscean, find the pronoun that corresponds and use the possessive form of its Piscean equivalent. For example:

- Teet bee meen! - that is mine! (literally, 'that is my!')

- Teet bee jor - that is yours (literally, 'that is your')