An explanation for the counterfactual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences

What is this paper about ?

Well imagine you heard a sentence starting "if she left tomorrow ..." and a sentence starting "if she leaves tomorrow ...". Which form suggests the least chance of "she" actually leaving. Well (assuming English is your mother tongue) you will feel that the first form (if she left tomorrow ...) suggests the least chance of the action actually happening. We can say that the first form is more counterfactual.

Looking at "if you left tomorrow ..." we see that the verb is marked past tense, yet we can see the action is for tomorrow, the future.

This has always been a bit of a mystery. What exactly is going on here ? Why does a past tense in a conditional sentence suggest counterfactuality ?

I hit upon the solution late May 2018. At first I thought I must have merely rediscovered something that was already common knowledge ... but apparently not.

My solution is based on two very simple ideas. The first of these ideas is detailed in the section "What people talk about". As far as I know this idea has never been expressed before. It is an extremely simple idea. Maybe before nobody thought it was worthwhile saying. The second of these ideas has been around for sometime and is now commonly agreed on as the way grammaticalization works. It is summarised in the section titled "How people find meaning in what they hear".

..

..... Start of rewrite

DELTA WING DIAGRAM ... Algebra existed for a long time with very little progress being made : all through the Greek Age and the Roman age and the Middle Ages. It was only when an efficient notation was devised that people could started to manipulate the different terms and progress was made in Algebra.

Discuss the German paradigm

Comrie 1986 ... like to read

Comrie says cf from past tense can be easily cancelled (page 33 of Jesus)

..

..... X-phrases

..

All through the Greek Age and the Roman age and the Middle Ages mathematics was divided into only two subfields, arithmetic and geometry. Then in the 16th century Algebra came to light. The key idea behind algebra is to use a symbol to represent a number that can vary. Commonly a number of these symbols/variables co-exist in an equation and when you solve an equation for a certain symbol/variable, you have reduced the range that that symbol /variable can represent as far as possible (in beginner's algebra, invariably the range is reduced to one particular number) given the constraints of the equation or equations available.

Today algebra is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics. It seems like mathematics only really got into its stride when symbols were devised for variables along with rules for manipulating them. Algebra is at heart the adoption of an efficient notation that lets us manipulate quantities relatively rather than absolutely. In the Western Mathematical Tradition, x is the preeminent name/symbol used for an independent variable. This tradition was started by René Descartes in La Géométrie (1637). As a result of its use in algebra, X is often used to represent unknowns in other circumstances (e.g. X-rays, Generation X, The X-Files, and The Man from Planet X).

It seems to me that X is useful in three situations (but probably these situations run into each other and what we have is a continuum rather than three discrete situations)

1) General ……. X = A + B ……. A and B can vary, but the expression will always hold.

2) Unknown …………. X is unknown (but at a certain point in time, maybe new data will come forward which will allow X to be resolved.

3) “Too awkward to express” …… X = sqrt (9-2) …. You can not express this absolutely. It is an irrational number and never ends. However you can express it relatively by means of ½, 9 and 2.

..

There is a linguistic construction called "the headless relative clause” in the Western Linguistic Tradition. (However I prefer the term X-phrase (my coinage). For one thing, an X-phrase is perhaps more basic than a relative clause so I don’t think its name should be derived from “relative clause”.)

Here also we have …

1) General .......... Geese fly South [when the first snow falls]

2) Unknown ……. I will leave [when you arrive]

3) “Too awkward to express” …… [When John gave Mary a flower] ….. If you wanted to express it absolutely you would have to say “at three fifty five in the morning of Monday the twenty eightth of November, 2018". However you can express it relatively by means of “John”, “give”, “Mary” and “flower". (I show X-phrases in square brackets above)

..

In English, X-phrases are based on QW’s (question words). For example “why” = “the reason is unknown (to me)” + “I want to know”. When “why” is used in an X-phrase the meaning has been reduced to “the reason is unknown”.

(There is another usage of “why” : the rhetorical question usage. This usage appears to lie between the two usages discussed above. In the rhetorical question usage we have “why” = “the reason is unknown” + “I want to know”, but the second element has faded, you could say it is there in body but not in spirit.)

English has 7 question words ... when, where, who, what, how, why, which ... enquiring about time, place, thing, person, manner, reason and "one from a group of identical things". Dropping “which” (which is a slightly different kettle of fish), we have ... when, where, who, what, how and why.

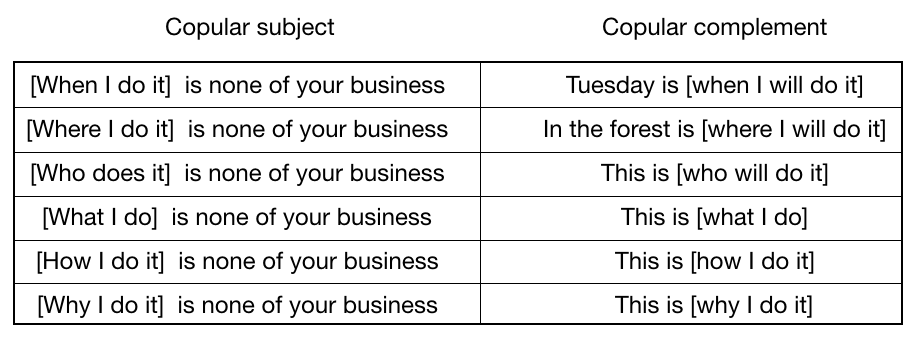

X-phrases derived from the above 6 QW’s are particularly common as copular subjects and copular complements, cf. “what you see is what you get”. The ability to stand in for nouns in other situations is sometimes restricted though. i.e. if the underlying situation is “John gave Mary a flower on Monday”. We can substitute for “John” by “who gave Mary a flower on Monday” in copular subjects and copular complements, but if you wanted to use it as a sentence subject, it sounds a lot better to say “the guy who gave Mary a flower on Monday …”.

The first 2 QW’s (when and where) however can form X-phrases almost anywhere. The other 4 have varying degrees of restriction on their usage.

..

Examples of X-phrases as copular subjects and copular complements ...

..

..... The X-Factor

..

All through the Greek Age and the Roman age and the Middle Ages mathematics was divided into only two subfields, arithmetic and geometry. Then in the 16th century Algebra came to light. The key idea behind algebra is to use a symbol to represent a number that can vary. Commonly a number of these symbols/variables co-exist in an equation and when you solve an equation for a certain symbol/variable, you have reduced the range that that symbol /variable can represent as far as possible (in beginner's algebra, invariably the range is reduced to one particular number) given the constraints of the equation or equations available.

Today algebra is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics. It seems like mathematics only really got into its stride when symbols were devised for variables along with rules for manipulating them. Algebra is at heart the adoption of an efficient notation that lets us manipulate quantities relatively rather than absolutely. In the Western Mathematical Tradition, x is the preeminent name/symbol used for an independent variable. This tradition was started by René Descartes in La Géométrie (1637). As a result of its use in algebra, X is often used to represent unknowns in other circumstances (e.g. X-rays, Generation X, The X-Files, and The Man from Planet X).

Should we call QW's used in this fashion X-words ? and the function they fulfill the X-function ?

It seems to me that in English (and other languages), when a question word can be used to produce a phrase with relative meaning, we have an (exact ?) analogy to the use of x in mathematics. The flexability of usage that these phrases gives us mirrors the flexibility that the use of x gives us when doing mathematics. English has 7 question words ... when, where, who, what, how, why, which ... enquiring about time, place, thing, person, manner, reason and "one from a group of identical things".

..

..

The first two QW's can be X-words anywhere. The next four can be X-words but they all have restricted distribution. The last one (which), after a pause, refers back to a resent proposition. When immediately after a noun it is a relativizer.

How what I call the X-function has been traditionally been called a "headless relative clause".

In English the preeminent "relativizor" is "that". In certain situations five English QW's can be used as relativizors. That is : the time when ... : the place where ... : the kid who ... : *the man what... : *the manner how ... : the reason why ... : the one which.

But I digress a bit ... back to the X-function.

In language, we use the X-function in two main situations ... when X is unknown, when X is general ?, and when X is too difficult to express.

For example ...

A) "Where there's muck there's brass" ... unknown ?

B) "When Paul arrived home his wife had already left for the market" ... too difficult to express ... perhaps 14:35 Wednesday 21st of November.

and

C) X = A + B

D) X = sqrt(9-2) ... this is an irrational number. That is, it is infinitely long.

...

In the case of (B), the time is expressed in terms of "Paul" and "arrived home".

In the case of (D), X is expressed in terms of "1/2", "9" and "2".

...

Is this an exact analogy ? Is it a rough analogy ? Is it an exact analogy in certain ways ?

What has been previously written about this subject ?

...

In languages there can be connections between QW's, X-words and relativizers. Also a language usually has a few ways of expressing different indefinites. Often some of these ways are entangled with QW's as well. c.f. English "whatever", "whoever", etc.

However I would like to focus the conversation to QW's and X-words (for simplicities sake).

It seems to me that QW's have to components ... i.e. who =>

---

It has often been suggested that for those languges which use non-specialized intra-clausal markers (i.e. past tense) to encode counterfactual conditionals, counterfactuality can be easily cancelled (cf. Comrie 1986: 89).

---

Not a relativizer !

---

I should write about how "thought" is more irrealis than "think" ... but only a little bit

---

..... DIVIDER

.. ..

..... Terms

..

A "conditional sentense" is basically* a sentence beginning with "if" that consists of two clauses

I call the clause containing "if" the antecedent, and the other clause the consequent.

These names are derived from Latin, meaning "what goes before" and "what follows".

But notice in English, "what goes before" can follow, and "what follows" can go before.

English indicates which is the antecedent and which is the consequent by having "if" to the left of the antecedent. Mandarin differentiates between the two by having "rúguǒ" to the left of the antecedent and "jiù" to the left of the consequent. The English "then" can be thought of as equivalent to "jiù". However English "then" is not mandatory, or even common, in this position.

..

*Sometimes you come across an "if" that can be substituted by "whether". This is NOT a conditional sentence. Also sometimes you come across "if" in the phrase "as if". This is also not a conditional clause. I believe all other occurrences of "if" signifies a "conditional sentence" (I think)

..

..... Preamble

..

We will throw some light on this later. But for now lets talk a bit about "if" and "-t" as in ... "if you left tomorrow ..."

"if" marks the antecedent of a conditional sentence. It tells you we are talking about a contingency*. As far as I know all languages have ways of expressing contingencies. They are just too important to do without. If somehow “if” were to be banished overnight from the English language I can see something being quickly roped in to express this role … perhaps “ink” <= “in case” or something similar.

And of course "-t" expresses past tense. WALS reckons that about 60% of the world languages have a past tense ... http://wals.info/feature/66A#6/-7.856/290.625 ... [Feature 66a]

Below I will argue that if a language possesses these two components, then it is highly likely that past tense in a conditional sentence will acquire a certain shade of counterfactuality.

Now with so many of the world languages possessing this shade of counterfactuality, a counterfactuality forged by exactly the same forces, it would be useful to give this counterfactuality a name.

I would suggest "the ngali** counterfactual" ... pronounced [ŋgali]

..

..

In the above diagram you can see that the consequent always follows on from the antecedent. That is shown by a thick black line. But how much does the speaker of the conditional sentence insist it is real. Well that can vary a lot. (For the moment lets restrict our self to telic events that will happen in the future ... we need to simplfy to see the wood from the trees.)

The speaker can have 100%*** confidence that the event will take place (A). Or the speaker can be 100% confident that the event will NOT take place in this Universe (C). He is talking about an alternative Universe. However since this alternative Universe has the same physical laws as this Universe, since the people behave similar to people in this Universe, there is wisdom to be had by listening to conditional sentences set in this alternative Universe (i.e. by listening to counterfactual conditional sentences)

The chances of an event happening in the future is somewhere between 0 and 100%. Why not spit the difference ... lets call (B) 50% ... for demonstration purposes only. The future is always uncertain ... things turn up thwart the antecedent.

..

.* I am calling "contingency", the situation where one event/state affects the chances of another event happening or state existing. This paper is about the conditional sentence usually introduced by "if" in English. However another type of contingency is sometimes introduced by the particles “however/but" in English. As far as I know this contingency does not have a special name.

.** Other names I have considered are "the accidental counterfactual" and the "half-assed counterfactual".

.*** Actually n English the speaker would use "when" instead of "if" in this situation.

[Some might ask why we need to give it a special name. If this counterfactual exists in every language with a past-tense, why not just call it the "past-tense-counterfactual". But perhaps "past-tense-counterfactual" is not specific enough : it doesn't distinguish between "past tense" meaning and "past tense" morphology. Any thoughts ?]

..

..... How people find meaning in what they hear

..

One example of a particle's meaning getting refashioned

..

Looking up the meaning of a word on an online device or even in a bookform dictionary is a very modern habit. But I guess children have always ask the meaning of a word occasionally ...

Q. "Daddy, what does dour mean ?" A. "Well Johnny, its means something like unhappy."

Usually they are given a very rough and ready equivalent. But it is enough ... and after Johnny hears "dour" used 7 or 8 times in conversation, he has a pretty good idea when it is appropriate for he himself to use the word.

However most words are learnt by children without having to ask explicitly. Also I have never heard a child ask about the meaning of a particle (those short common words that have a grammatical meaning).

Q. *"Daddy, what does "if" mean ?.

Q. *"Daddy, what does "since" mean ?.

[A star, as above, before a sentence means "does not occur"]

Because of this method of children (and other language learners) picking up the meaning of a word from from the environment/situation it is usually found in. Well it can facilitate the spread of meaning a word or particle might have, into other areas. As an example of this, lets look at the English word "since". Nowadays "since" can be said to have two meanings, “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time” and "because".

But if we visited "since" in an earlier era, we would find it only had one meaning, ... “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time”.

At that time we would hear such expressions as ...

A) I haven’t eaten since breakfast.

B) Our local football team hasn’t been doing so good since Peter McCallum broke his leg.

Now the speaker of English only thought "since" in the above two examples meant “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time”. However a language learner, hearing "since" in a sentence such as (B) might think it meant "because". And this is exactly what happened. And a generation or two later, we would hear expressions like ...

C) Since you’re so clever, you work it out yourself.

Perhaps nowadays in speech, 75%* of the time you here "since" it means “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time” and 50% of the time it means "because. This makes 125% of course. Perhaps a quarter of the time it can mean either.

If one meaning of a word significantly outweighed its secondary meaning(in terms of frequency) it denoted the first meaning and connoted the second meaning (“denoted” and “connoted” are cognates by the way). However in the case of "since" this is probably not appropriate as both meanings occur equally frequently ... more or less.

When a grammatical word (particle) changes its meaning, often the original meaning is lost. Or alternately the two different usages can quite happily live on in parallel indefinitely. Presumably in the latter case, the ambiguity does not cause that much confusion.

More can be said about particles/affixes changing their meaning, but I think the above encapsulates the basics quite well.

..

* Of course this is a rough ballpark figure.

..

..... What people talk about

..

Near my home I have a friend called Jim. He is from Canada and has spent time his adult life in the Canadian army and as part owner of construction company building private homes. I chat to Jim every day.

Now the diagram below represents what Jim knows. We can look upon these hexagons as "facts". The facts to the top are based on the facts further below. We can call all the fact that he knows his "system of knowledge".

..

..

Jim is learnimg new facts everyday. I like to tell Jim new facts that will interest him. This is how friends behave.

..

One facts that I would not say to Jim is ...

This is an old fact. While it is true, I do not want to bore Jim by saying it.

..

Another facts that I would not say to Jim is ...

The Slavic perfecrive/imperfective distinction is unmarked either way

The Slavic perfecrive/imperfective distinction is unmarked either way

The fact is true. However for this to fit in with Jim's "system of knowledge" I would have to fill Jim in with a lot of sub-facts, I would have to spend all morning teaching him about linguistics. Jim trusts me and could remember what I said. In which case maybe he could be said to "know" the fact, but for him to "understand" the fact, all the hexagons between his "system of knowledge" and the blue dice would have to be filled in.

..

The facts that would be of most interest to Jim are facts around the limit of his "system of knowledge". Some statements can fill in two hexagonals simultaneously. For example if yesterday Jim knew "Maybe Paul will play golf today", then today if I tell Jim

Paul really enjoyed his game of golf yesterday

Paul really enjoyed his game of golf yesterday

I I give Jim two facts ... "Paul played golf" + "Paul really enjoyed it". [The former fact is a brick red hexagon in the schematic, the latter fact is a red dice]

..

If yesterday Jim heard "If Paul's wife comes home from the market before midday, he will take her to play golf", then by telling him "Paul really enjoyed his game of golf yesterday" I fill in three hexagons ...

"Paul's wife came back before midday" + "They went to play golf" + "Paul really enjoyed it"

People don't like to be boring. They like to fill in as many facts with one utterance as possible.

One side effect of this is that ...

..

if a conditional situation has been resolved, only the resulting state will be reported, the conditional sentence will never be repeated ... [This is my little hexagon to the world :-) ]

..

..... Tying things together

..

In the last section we stated ... if a conditional situation has been resolved, only the resulting state will be reported, the conditional sentence will never be repeated

And in the section before that we stated that people decide on the meaning of particles/affixes depending on the environment in which they hear them.

So, putting the above two statements together ...

A) Conditional situations are resolved when they are in the past i.e. when the antecedent has a verb marked past tense.

B) Conditional situations are unresolved when an event happens or a state exists which stops the antecedent from taking place.

C) People growing up, only hearing an antecedent with a verb having past tense morphology in counterfactual situations will start to associate "if" + "past tense" with conterfactuality.

..

SO SIMPLE ... why hasn't somebody twigged to this before?

..

Actually there is one complication, one fact that muddies the waters a bit.

There is one exception to the rule ... if a conditional situation has been resolved, only the resulting state will be reported, the conditional sentence will never be repeated

D) If a conditional statement has been resolved, but somebody doesn't know how it was resolved (i.e. doesn't know if the action in the antecedent actually took place or if it was blocked somehow) then they will repeat the conditional sentence.

This has the practical effect of making the past tense counterfactual a bit vague, it makes it a bit wishy-washy.

In the following section I attempt to describe this vagueness and how it comes about. Some might say that the next section is unnecessary. Maybe, however I think very visually and I like colour schematics of interesting shapes. I feel understanding the next chapter certainly gives me a deeper understanding of the past tense counterfactual. Hopefully other people can also follow it and appreciate it.

..

The whole idea of the thought experiment is to explain ...

..

In the above schematic there is a horizontal axis marked zero to 100. The yellow/orange bar represents "percentage counterfactuality", I would give (either disseminating information or receiving information) as a native English speaker to hearing/speaking an antecedent with "if" + "past tense". I drew the two boundaries as "hard" at 45% and 90%. They should not be hard but slightly fuzz*. This is based one my native intuition so nobody can argue with me :-) . If "will" was used in the consequent the whole yellow/orange bar would move to the left a bit. If "would" was used in the consequent the whole yellow/orange bar would move to the right a bit.

Now all the values I give the following thought experiment should be taken with a pinch of salt. I am assuming a god-like control over the thought experiment so just as I can say that Puntu's grandmother is called Umara I can set any physical value in this imagined community. However this doesn't matter, all the thought experiment does is show how the past tense counterfactuality does not mean 100% counterfactuality. This would be shown also if I had picked wildly different numerical values. So relax and let your imagination take over. Be immersed in the world of Umara and Puntu ...

..

The little rule that I introduced in the last section can be amended to take into account of this exception. So the exceptionless rule would be ...

..

if a conditional situation has been resolved, and it is know how it was resolved, only the resulting state will be reported, the conditional sentence will never be repeated

..

Footnote ... [There are conditional situations which never get resolved. These are timeless truths and are called generic conditionals. For example "If you overeat, you will get fat". Another example is "if the bird pecks the correct lever, some seeds fall into this tray". Note that the last example, as well as being a timeless truth, can also be an actual event. So the last example represents a generic situation and also an eventive situation. Generic situations never take a past tense hence do not contribute to the past-tense/counterfactual conflation. Of course the counterfactual meaning, after it has been established via eventive situations can be applied to generic situations. For example "If you overate, you would get fat"]

..

*Probably we are leaving linguistics here and getting into the subject of "how the brain works" here. I don't know how the brain works. But I would imagine some inbuilt features that reflect bayesian probability".

..

..... The thought experiment

..

Imagine a pre-industrial society. The fastest way of getting about is by walking : the fastest way of sharing information is by word of mouth.

[The above is important for my argument : the below is just adding colour]

Lets make this society an isolated village … comprising of about 200 adults ... perhaps in Southern Sudan ... about 20,000 years ago. It is a hot climate so people spend a lot of their life out of doors. Lets imagine these people as 200 dots on a piece of paper. You can see these dots mingling/moving about ... a bit like seeing brownian motion in a petri dish.

..

..

These people have a language. Lets call it the thought experiment language (TEL). TEL is remarkably like English. It has a past tense (PST), non past tense (NPST) distinction. PST is represented by the affix “-ed”, NPST is unmarked.

No perfective/imperfective distinction or perfect. Lets keep it simple.

Assume here that “-ed” has only past tense meaning in all environments … maybe only grammaticized a few days ago (I know, unlikely, but please bear with me). There is no future tense … well they have a word meaning “intend” but it hasn’t been grammaticized yet. For human subjects with volition "intend" usually translates the English future tense. For non-sentient subjects, such adverbs as "soon", "tomorrow", "next year" suffice to show the future.

..

Building the scene

..

Old Umara is feeling poorly. She loves blood-pudding. Her grandson Puntu is to undergo the initiation into manhood rite quite soon. Only adults from Puntu’s family and the village shaman may attend. The rite is held in the shaman's hut. To encourage Umara out of her sick bed, Puntu's mother and elder sisters dangle the prospect of blood-pudding. One of the talking points of this community (the word on the street) is …

(1) “If Umara attends* Puntu’s event, they intend to serve blood-pudding.”

Now (1) is a valid statement right up to the time of the rite.

The event is to happen at midnight on the first day of the new moon. All the community knows this.

After the event (1) is no longer valid, but (2) is valid ... (2) = “If Umara attended Puntu’s event, they intended to serve blood-pudding.”

Now after the rite, news of it will spread … people meeting and chatting like they do.

Now lets go back to our piece of paper with these dots. Imagine if you will a cone under the piece of paper. The point of the cone meets the piece of paper at one point. This point on the paper is the position of the shaman's hut. Sheet of paper is 2-D, cone is 3-D, so we have introduced another dimension. This is the dimension of time. The point where the sheet meets the cone is the place and time of the event (the rite). The cone can be thought of as a “cone of knowledge about the event”. Of course the cone as an idealized shape, the actual shape of the “knowledge volume” will be quite irregular as it depend upon people going about their usual business and chatting together.

..

..

Anyway … the point I am trying to make is that in a short period of time, everyone in the village will know of the event, they will know if Umara managed to go to the rite. If she, in fact, attended the rite, (2) is obsolete. You would only hear (2) if Umara had been too sick to attend. Assuming that there was a 50% chance that Umara made it to the rite. To account for all eventualities we construct two universes*** ... one in which she attended the rite, and one in which she didn't.

..

..

... The green represents blue plus yellow.

... The green represents blue plus yellow.

..

It is worth emphasizing again ... IN UNIVERSE 1, (2) WILL NEVER BE SAID AFTER THE PERIOD OF IGNORANCE IS PASSED ... I guess this is the kernel of my whole proposition. ..

If you do the maths (that is compare the yellow volume to the light blue volume) you will find that (2) is pronounced in situations of ignorance 28 % of the time and in counterfactual situations 72 % of the time.

Hence it is inevitable in this community that a clause containing “if” + “-ed” quickly gets associated with counter factuality.

Now in TEL (as in English), “if” + “-ed” is nearly completely associated with counterfacuality. Hence the PST/NPST distinction has been lost. This distinction might be missed. Maybe there will be a future developement***** in the language to re-instate this distinction.

Remember at the beginning of this section I said "-ed" meant past tense in all environments. However after about 80 years (all the population has changed) this will no longer be true. In one environment (the antecedent clause) "-ed" will mean, more or less, counterfactuality

..

.* Notice that in TEL as in English. “if” plus a verb in indicative mood produce a verb with future** meaning. This isn’t surprising as the main point of conditional sentences is to evaluate contingencies ... to make plans for the future.

.** Just to complicate things a little. We can say that there are two types of verb. Telic verbs and Stative verbs. Telic verbs are verbs where an outside observer would see something happening. “drink” is such a verb. Stative verbs are verbs where an outside observer would not see anything happening. “believe” is such a verb. “if” plus a telic verb in indicative mood produce a verb with future meaning. “if” plus a stative verb in indicative mood produce a verb with future meaning, however this future meaning stretches down to the present (time of speaking). It is this tense that is the most pertinant hence it is said … “if” plus a stative verb in indicative mood produce a verb with present tense meaning.

.*** To account for this you could imagine that the universe split at the time of the rite. Resulting in Universe 1 where Umara attended the rite and Universe 2 where Umara failed to attend the rite. But don't worry your head about this, I am not advovating the "multiverse theory". An alternative way is to look at thing is that there is only one Universe, and some times future contingencies discussed happen and sometimes they don't. I am too lazy to dream up another contingency so I am going with the "multiverse" view. But it doesn't matter one way or the other ... this paper is about linguistics and not theoretical cosmology.

.**** I am of course thinking of English using “if” + “pluperfect” to indicate “counterfactual past” … I guess this would be a secondary developement happening after the past tense was lost.

..

..... Assumptions I have made

..

4 constants that I picked

(a) Radius of the community is 4 km

(b) Speed of propogation of information is 1 km/hour

(c) Time that disinterest sets in is 16 hours

(d) A considered future conditional situation will actually materialize half the time.

..

3 things that I assumed

(a) The community area has uniform population density

(b) People are equally talkative 24 hours a day

(c) Disinterest is sudden instead of gradual

..

It doesn't really matter, but say "rate of utterance of (2)" = 0.2 per kmkmhour (i.e. utterred 0.2 times in a square km over a one hour period)

..

Now these are just assumptions I have built my model on. If you change any of these you will get a change in the amount of counterfactuality implied by "if" + "past tense". However it will not change the basic counterfactuality distribution ... i.e. something like this ...

... the large volume in "unknown" (the yellow) stops the "if" + "past tense" ever being accepted as 100% counterfactual.

... the large volume in "unknown" (the yellow) stops the "if" + "past tense" ever being accepted as 100% counterfactual.

..

Now of course I have used only one example of a telic verb using a third person singular subject (Umara) in the antecedent and third person plural subject (they) in the consequent. If first person or second person were in used in any of these positions the amount of "unknown" would be reduced. Also the thought experiment might be non-representative of most conditional situations in that the time of the event is fixed and known by the whole community. But I will say it again, if a language learner averages out the counterfactuality in all the thousands and thousands of different past tense conditional sentences they hear as they are learning the language, the counterfactuality they will come to associate with "if" + "past tense" will be around about the range I have given in the above diagram (45% - 90 %).

..

So a language learner brought up in Puntu's community ... if he wanted to say "If you leave tommorrow ..."/"if you left tomorrow ..." ... well low levels of counterfactuality he would of course say "If you leave tomorrow ...". As the counterfactuality of the situation increases, he has the choice of saying "If you left tomorrow ... ". In the interests of being precise he would probably switch over to saying "if you left tomorrow". He would use this right up to 100% counterfactuality. However if he wanted to impress on his listener that the contingency was 100% counterfactuality, he would have to add the tag " ... but you won't leave tomorrow", if he wanted to impress on his listener that the contingency was 95% counterfactuality, he would have to add " ... but you probably won't leave tomorrow",

But usually it is thought unnecessary to define the amount of counterfactuality this precisely. Should we specify how blue the sky is or how green the grass is, when we utter something.

..

..... How counterfactual

..

Now primary function of the English word "if" is to indicate contingecy. It's job is not to show counterfactuality, so it ranges over the entire counterfactuality range ... well nearly.

Below I have drawn 4 sketches graduated 0 => 100. This represents degree of counterfactuality. At zero you have a event/state which is dead certain, at 100 you have something which will definitely not happen.

"if" [bluish] is represented in the top sketch. You notice that it spans nearly the entire counterfactuality range. Only when something is held to be totally real or realizable does it disappear. In the extreme left of this continuum "if" would be replaced by "when" in English.

This division is not really necessary. The German particle "wenn" [pinkish] is shown in the second top sketch. As you see it covers the entire continuum.

The third sketch represents "if" + "past tense". Notice that it does not go all the way to the right. The explanation for this is the considerable amount of "unknown" that contributes to its meaning (remember the volume coloured yellow in U1 and U2 (U = Universe).

..

... the height of the colour bars don't signify anything ... purely cosmetic.

... the height of the colour bars don't signify anything ... purely cosmetic.

..

The bottom sketch represents the Slovenian particle "da". Slovenian also has the particle "bi" for expressing contingency. I presume 'bi" would have a distribution similar to "if" or "wenn" if it was sketched, but with it stopping about where '"da'" starts.

Because of the distribution of "if" + "past tense" (its RHS cut-off point in fact), to make sure a proposition is understood 100% as counterfactual you have to add a "tag" to the to an "if" + "past tense" conditional sentence. For example, to "if you left tomorrow, you would arrive on Tuesday" you would have to add the tag* " ... but you can't leave tomorrow".

Various languages have such strong counterfactuals as Slovenian. Usually these strong counterfactuals have other functions in their language. I suspect the strong counterfactual meaning is the derived meaning (as "because" is the derived meaning of "since"). I would expect these strong counterfactuals to be more prevalent in languages with no past tense (maybe these WALS people could map "strong counterfactual" against "no past tense")

The strong counterfactuals in the various languages that possess them, may all have come about by different processes and hence all have slightly different ranges (an interesting topic for further research), however all the "if" + "past tense" languages should have a very similar counterfactuality range. [Note to self : is this right ? is there more complications?]

..

*A tag would not be necessary for the Slovenian counterfactual "da". In fact it would be ungrammatical.

..

..... How important is counterfactuality

..

How important is counterfactuality?

The answer is NOT VERY.

There is no great demand for counterfactuals. Imagine hearing "if I was a billionaire, I would fit out a boeing 747 for my personal use". If the hearer knew the speaker to be a lazy dreamer too fond of his grog, then it is quite obvious that we have a CF situation. And on the occasions when knowledge of the background situation doesn't shout out "counterfactual", it is easy enough to append "... but that isn't going to happen".

In Thai you quite often hear สมมติว่า "sɔɔmut waa" at the beginning of an utterance. It means "imagine that". When Thai people want to express counterfactuality, they get by perfectly well with this construction.

By the way, ถ้า "thaa" is the non-counterfactual antecedent marker, the Thai equivalent to "if".

..

So the truth is ... WE DON'T HAVE TO BE LIKE SPOCK* ...

.* It is well known that Vulcan has at least seven** particles, corresponding to "if", to represent different degrees of counterfactuality.

.** Well it depents on the dialect. It is rumoured that in the Hesperian Region there is a local dialect that expresses 11 different degrees of counterfactuality :-)

..

... Contingency

..

Well Contingency is what I call it. I don't know what other people call it. In fact I don't know whether anybody has ever considered these matters before.

Contingency comprises of conditional sentences and blocking sentences.

First lets introduce some terms ...

..

..

Lets go over the conditional sentences first.

X is the proposition "George is successful"

Y is the proposition "George has many friends"

The below schematic represents the conditional sentence "If George is successful, he will/would have many friends" ... (1)

..

..

The above schematic represemnts what sentence (1) asserts.

However there are two other combinations of the two proposition which are not inconsistent with (1)

"where George is not successful but has friends*" and "where George is not successful and does not have friends".

The only combination which is inconsistent with (1) is "where George is successful but does not have many friends". This is shown below ...

However making "If it was not for the fact that George is successful he wouldn't have many friends" = (2)

We can say (2) is consistent with (1). I show (2) below using my symbolic system ...

..

..

I call (2) a blocking sentence. This is a situation where a desired or envisioned event is blocked by a certain event or state.

..

In English the "it" in the antecedent refers to "George is successful" which is given in the form of a complement clause in (2). The "not" in the antecedent is outside the complementary clause and has scope over the entire clause (as opposed to the consequent, where "not" has only scope over the predicate).

In blocking sentences the antecedent can be a full clause (as above), but more often it is reduced to a noun phrase containing an infinitive or a participle or similar. For example ...

"But for you, we would be successful" is a blocking sentence. In this case "but for" introduces the antecedent.

In English there are a number of phrases that can introduced the antecedent.

A number of languages have a single word that introduces the antecedent of a blocking sentence.

For example yaobushi in Mandarin or kundi in Tagalog. (Two languages without a past tense ... I wonder if a language with out a past tense is more likely to use a blocking sentence, and hence have a one word particle that introduces the antecedent of a blocking sentence.

I believe that these words are a different kettle of fish from the words that introduce a conditional sentence antecedent with strong counterfactual meaning (such as ... Slovenian da, Modern Greek na, Arabic law, etc. etc.

I believe that if you are to do a typological study of conditional sentences, it would also be rewarding to include blocking sentences. They seem to have functions that are not entirely separate hence patterns in one could be reflected in the other. Hence I like to talk about "contingency'.

..

.* Notice that this interpretation can be forced by giving some backgroud information. For example ...

Speaker 1 ... "George is very amusing and his quick wit has gotten him many friends."

Speaker 2 ... "If George was successful, he would also have many friends."

..

... Wanting/wishing

..

It is not only "if" that mixes with past tense to give counterfactuality. There is one other place where it occurs cross-linguistically.

Now this is a bit awkward to discuss in English. English has a verb "want" and a verb "wish". The latter is a lot rarer and has strong connotations of counterfactuality. Cross-linguistically it is more common for a language to have one word that encompasses the two meanings. From now on I will refer to "want/wish" ... to better reflect the general situation in the wider world.

Now "want/wish" can team up with a past tense to give counterfactuality. The situation mirrors what we discussed previously in our thought experiment.

(1) Puntu wants/wishes Umara attends the rite.

(2) He wanted/wished Umara attended the rite.

..

..

This one is slightly different in two ways.

(A) The past tense is in what is called a complement clause.

(B) "want/wish" is a normal verb. The tense on this verb does not interact with the counterfactuality.

Whereas before ... "if" + past tense => counterfactuality

Now we have ... "want/wish" + past tense(in the complement) => counterfactuality

..

... Would and could

..

Actually a very similar process has happened in non-conditional environments for the words "would" and "could" (in origin, the past tense of "will" and "can") in English. For example the sentence “she said that she would come to the party” … this has strong connotation of counter-factuality simply because, if she had actually come to the party, “she said that she would come to the party” would not be worth saying … “she over-indulged with the tequila slammers and surreptitiously spewed in the flower-pot” would be worth saying … “she met a charming young Russian ornithologist and slipped out with him early” would be worth saying, but “she said that she would come to the party” would not be worth saying.

..

For people, for them to take some action, two things are necessary. They must have the inclination(the will) and the means.

1a) Umara will attend the rite

1b) Umara can attend the rite

..

And after the rite happens, we have ...

..

2a) Umara would attend the rite

2b) Umara could attend the rite

..

And at their inception they would have entailed the same mixture of counterfactuality and ignorance which we have met before. [What about reported speach ??]

..

Well that is the etymology of the word "would". Over the years its usage and meaning has changed a bit. (1a) in modern English would be "Umara wanted to attend the rite". The usage of "could" has also changed over the years, but to a lesser extent.

..

能 [néng] : can, be able

会 [huì] : meet, can, able

..

... Post Script

..

There is something a bit strange in the "if" + "past tense" counterfactual in that two elements combine to give one meaning. And these two elements are not adjacent. Maybe some people subscribe to a linguistic theory where this is not possible. If you do follow such a theory ... well ... I suggest you amend your theory :-)

I hope I have explained why (by way of typical human interaction) "past tense morphology" (by itself straight forward and unambiguous) plus "if" (by itself a pretty straight forward marker of conditional sentence) have come together. And together have a meaning "around 70% or 80% counterfactual".

Up until now it seems most people have considered counterfactuality as either present or absent. I think this is wrong. To fully describe a counterfactual form you must give two percentages ... N1 and N2. N1 is the lower limit of a counterfactual form and N2 the upper limit.

Also it seems to me that there has been a lot of head-scratching over a little thing called "cancelability". It is quite easy to explain under the system I has devised (in fact it is not worthwhile to even discuss it). Simply put ...

..

The lower N1 is the easier it is to cancel a counterfactual sentence.

I look upon the ngali counterfactual as an inevitable process. Well an inevitable process if there are no pre-existing strong counterfactuals in a language having a past tense. It would be interesting to see if Slovenian, for example, pocesses an ngali counterfactual. Strong counterfactuals are worthy of investigation. Are they all formed under different linguistic influences, that is have they all had different pathways to grammaticization. Or perhaps they all share the same pathway to grammaticization. Or alternatively, maybe all the world's strong counterfactuals can be sorted into a few subtypes. If so does N1 ( I presume N2 of a strong counterfactual to be 100) of each subtype have they same value or can other "language specific" parameter pull N1 up or down ?

Maybe not really necessary to add, but here goes ... all languages have means of localing events in time. However only about 60% of languages have a past tense. And when I say past tense, I mean that there is obligatory marking (usually on the verb) when the event/action happened prior to the act of speaking. For the remaining 40% of languages it is not obligatory to mark a past tense. And when they do, they use a variety of means ... like adding "before" or "already", or "yesterday" or "next week" etc. etc. None of these adverbs is seen co-occurring with conditional markers ( i.e. "if") to a high degree in counterfactual situations, so no counterfactual connotations evolve.

..

..

There have been a few explanations as to why past tense morphology takes up a counterfactual meaning. Sabine Iatridou talks of something called an exclusion operator. She has an excellent paper outlining counterfactuality in many languages IATRIDOU 2000 ... http://lingphil.mit.edu/papers/iatridou/counterfactuality.pdf <http://lingphil.mit.edu/papers/iatridou/counterfactuality.pdf

The paper is about 40 pages in all. The pages numbered 246-249 try and explain this exclusion operator (or ExclF as she calls it). I found no enlightenment between pages 246 and 248, only bewilderment. Great mental gymnastics are performed but she ends up in a knot.

Another explanation says that metaphor is involved ... something like "not real" < "far away < "far away in time". All I can say to that one is FAR FETCHED.

..

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel

..