Counterfactuality

Paper Title : "A statistical explanation for counter-factual/past-tense conflation"

I believe I have hit upon why past tense morphology often is associated with counter-factuality in conditional sentences. To my knowledge, this hasn't been stated before so I thought I should pass it on somehow. Hence this paper.

I asked an academic what was the latest/best thinking on this topic and was recommended "Iatridou 2000" ( http://lingphil.mit.edu/papers/iatridou/counterfactuality.pdf ).

Now while Sabine Iatridou gives an excellent overview of how languages align themselves with respect to conditional, counter-factuality, subjunctive, imperfective, habitual and what have you, her explanation as to why things are the way they are leaves a bit to be desired. She postulates an "entity" she calls ExclF which is behind both past tense and counter-factuality. Surely it would be simpler, if there was an overwhelming need* to indicate counter-factuality, to have a particle/affix that denotes exactly CF and nothing else.

My explanation for the way things are (in many many languages) is that if there is a past tense/non-past-tense distinction and a particle ("if" in English) that introduced conditional sentences, then inevitably over quite a short period of time, a clause featuring both picks up a very strong CF connotation. In fact this connotation is so strong that the past tense meaning is subsumed.

I will express my idea in two parts. First going over the ways particles/affixes change their meaning over time. Then to do a thought experiments. The thought experiment reveals the main thrust of my idea.

.* But the truth is that there is no great demand for counter-factuals. Imagine hearing "if I was a billionaire, I would fit out a boeing 747 for my personal use". If the hearer knew the speaker to be a lazy dreamer too fond of his grog, then it is quite obvious that we have a CF situation. And on the occasions when knowledge of the background situation doesn't shout out "counter-factual", it is easy enough to append "... but that isn't going to happen" to the conditional sentence.

..

..... One example of a particle's meaning getting refashioned

..

Looking up the meaning of a word on an online device or even in a bookform dictionary is a very modern habit. But I guess children have always ask the meaning of a word occasionally ...

Q. "Daddy, what does dour mean ?" A. "Well Johnny, its means something like unhappy."

Usually they are given a very rough and ready equivalent. But it is enough ... and after Johnny hears "dour" used 7 or 8 times in conversation, he has a pretty good idea when it is appropriate for he himself to use the word.

However most words are learnt by children without having to ask explicitly. Also I have never heard a child ask about the meaning of a particle (those short common words that have a grammatical meaning).

Q. *"Daddy, what does "if" mean ?.

Q. *"Daddy, what does "since" mean ?.

[A star, as above, before a sentence means "does not occur"]

Because of this method of children (and other language learners) picking up the meaning of a word from from the environment/situation it is usually found in. Well it can facilitate the spread of meaning a word or particle might have, into other areas. As an example of this, lets look at the English word "since". Nowadays "since" can be said to have two meanings, “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time” and "because".

But if we visited "since" in an earlier era, we would find it only had one meaning, ... “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time”.

At that time we would hear such expressions as ...

A) I haven’t eaten since breakfast.

B) Our local football team hasn’t been doing so good since Peter McCallum broke his leg.

Now the speaker of English only thought "since" in the above two examples meant “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time”. However a language learner, hearing "since" in a sentence such as (B) might think it meant "because". And this is exactly what happened. And a generation or two later, we would hear expressions like ...

C) Since you’re so clever, you work it out yourself.

Perhaps nowadays in speech, 75%* of the time you here "since" it means “a time span from an event in the past up until the present time” and 50% of the time it means "because. This makes 125% of course. Perhaps a quarter of the time it can mean either.

If one meaning of a word significantly outweighed its secondary meaning(in terms of frequency) it denoted the first meaning and connoted the second meaning (“denoted” and “connoted” are cognates by the way). However in the case of "since" this is probably not appropriate as both meanings occur equally frequently ... more or less.

When a grammatical word (particle) changes its meaning, often the original meaning is lost. Or alternately the two different usages can quite happily live on in parallel indefinitely. Presumably in the latter case, the ambiguity does not cause that much confusion.

More can be said about particles/affixes changing their meaning, but I think the above encapsulates the basics quite well.

..

* Of course this is a rough guestimate.

..

..... Terms used here

..

In English you have a conditional sentence if you see the word "if"*.

There are always two clauses in a conditional sentence. They are logically distinct.

"If you come on Tuesday, I will bake you a cake" =/= "If I bake you a cake, you will come on Tuesday"

I call the clause containing "if" the antecedent, and the other clause the consequent.

These names are derived from Latin, meaning "what goes before" and "what follows".

But notice in English, "what goes before" can follow, and "what follows" can go before.

That is "I will bake you a cake if you come on Tuesday" is valid in English.

English indicates which is the antecedent and which is the consequent by having "if" to the left of the antecedent. Mandarin differentiates between the two by having "rúguǒ" to the left of the antecedent and "jiù" to the left of the consequent. (The English "then" can be thought of as equivalent to "jiù". However "then" is not mandatory, or even common, to the left of the English consequent.)

..

*Well two exceptions. If you come across "if" in the phrase "as if" you don't have a conditional sentence. Also if "if" can be replaced with "whether" with no change of meaning, you don't have a conditional sentence either.

..

..... Preamble

..

What is this paper about ?

Imagine you heard a sentence starting "if you left tomorrow ..." and a sentence starting "if you leave tomrrow ...". Which form suggests the least chance of the verb (to leave) actually being performed ?

After a moments consideration, it should be obvious that the first form suggests the least chance of the action actually happening ? We can say that the first form has more counter-factuality.

Looking at "if you left tomorrow ..." we see that the verb is marked past tense, yet we can see the action is for tomorrow, the future.

This has always been a bit of a mistery. What exactly is going on here ?

..

Well I will throw some light on this later. But for now lets talk a bit about "if" and "-t" as in ... "if you left tomorrow ..."

Well "if" marks the antecedent of a conditional sentence. It tells you we are talking about a contingency. As far as I know all languages have a means of expressing contingencies. Having a means to express contingencies is just too important to do without. If somehow “if” were to be banished overnight from the English language I can see something being quickly roped in to express this role … perhaps “ink” <= “in case” or something similar.

And of course "-t" expresses past tense. WALS reckons that about 60% of the world languages have a past tense ... http://wals.info/feature/66A#6/-7.856/290.625 ... [Feature 66a]

Below I will argue that if a language possesses these two components, then it is highly likely that past tense in a conditional sentence will acquire a certain shade of counter-factuality. I fact if a language has these components but lacks this shade of counter-factuality ... well THEN you have an enigma that should be investigated.

Now with so many of the world languages possessing this shade of counter-factuality, a counter-factuality forged by exactly the same forces, it would be useful to give this counterfactuality a name.

I would suggest "the ngali* counter-factual" [actually I would like to speak to somebody who knows the history of Swahili, before backing this proposal 100%]

..

.* Pronounced [ŋgali]

..

[What percentage of the world's languages have a "ngali counterfactual ? I don't know ... a third ??

[ Note to self : expand this a bit ... Even if it is just a word such as “wenn” in German … a particle which together with the antecedent produces an adverb phrase meaning “at the time of _______”. ]

..... My thought experiment

..

Imagine a pre-industrial society. The fastest way of getting about is by walking : the fastest way of sharing information is by word of mouth.

[The above is important for my argument : the below is just adding colour]

Lets make this society an isolated village … comprising of about 200 adults ... perhaps in Southern Sudan ... about 20,000 years ago. It is a hot climate so people spend a lot of their life out of doors. Lets imagine these people as 200 dots on a piece of paper. You can see these dots mingling/moving about ... a bit like seeing brownian motion in a petri dish.

..

..

These people have a language. Lets call it the thought experiment language (TEL). TEL is remarkably like English. It has a past tense (PST), non past tense (NPST) distinction. PST is represented by the affix “-ed”, NPST is unmarked.

No perfective/imperfective distinction or perfect. Lets keep it simple.

Assume here that “-ed” has only past tense meaning in all environments … maybe only grammaticized a few days ago (I know, unlikely, but please bear with me). There is no future tense … well they have a word meaning “intend” but it hasn’t been grammaticized yet. For human subjects with volition "intend" usually translates the English future tense. For non-sentient subjects, such adverbs as "soon", "tomorrow", "next year" suffice to show the future.

..

Building the scene

..

Old Umara is quite sickly. She loves blood-pudding. Her grandson Puntu is to undergo the initiation into manhood rite quite soon. Only adults from Puntu’s family and the village shaman may attend. The rite is held in the shaman's hut. To encourage Umara out of her sick bed, Puntu's mother and elder sisters dangle the prospect of blood-pudding. One of the talking points of this community (the word on the street) is …

(1) “If Umara attends* Puntu’s event, they intend to serve blood-pudding.”

Now (1) is a valid statement right up to the time of the rite.

The event is to happen at midnight on the first day of the new moon. All the community knows this.

After the event (1) is no longer valid, but (2) is valid ... (2) = “If Umara attended Puntu’s event …” ... (We are only considering the antecedent here)

Now after the rite (the event) news of it will spread … people meeting and chatting like they do.

Now lets go back to our piece of paper with these dots. Imagine if you will a cone under the piece of paper. The point of the cone meets the piece of paper at one point. In fact this point on the paper is the position of the shaman's ’s hut. Sheet of paper is 2-D, cone is 3-D, so we have introduced another dimension. This is the dimension of time. The point where the sheet meets the cone is the place and time of the event (the rite). The cone can be thought of as a “cone of knowledge about the event”. Of course the cone as an idealized shape, the actual shape of the “knowledge volume” will be quite irregular as it depend upon people going about their usual business and chatting together.

..

..

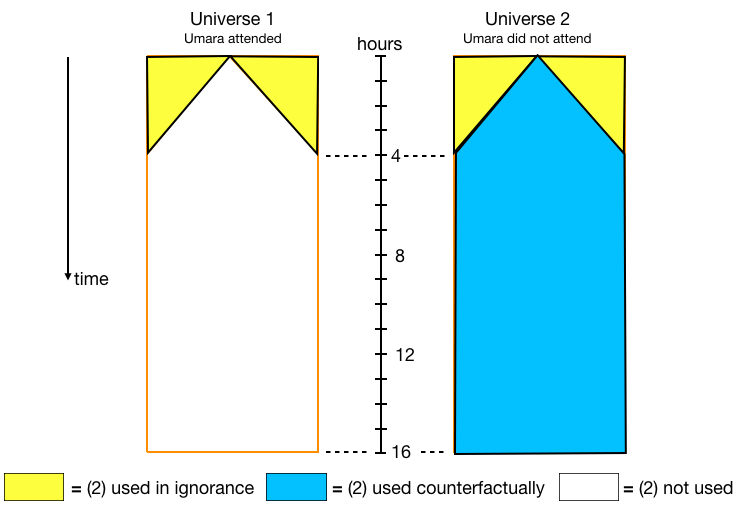

Anyway … the point I am trying to make is that in a short period of time, everyone in the village will know of the event, they will know if Umara in fact managed to go to the rite. If she in fact attended the rite (2) is obsolete. You would only hear (2) in the event that Umara was too sick to attend the event. Assuming that there was a 50% chance that Umara made it to the rite. To account for all eventualities we construct two universes*** ... one in which she attended the rite, and one in which she didn't.

..

..

The chart below I only produced because colouring-in 3D is too difficult for me. It is a 2D slice though the 3D volumes above.

..

..

It is worth emphasizing again ... IN UNIVERSE 1, (2) WILL NEVER BE SAID AFTER THE PERIOD OF IGNORANCE ... I guess this is the kernel of my whole proposition. ..

If you do the maths**** (that is compare the yellow volume to the light blue volume) you will find that (2) is pronounced in situations of ignorance 28 % of the time and in counterfactual situations 72 % of the time.

It is inevitable in this community that a clause containing “if” + “-ed” quickly gets associated with counter factuality.

Now in TEL (as in English), “if” + “-ed” is nearly completely associated with counterfacuality. Hence the PST/NPST distinction has been lost. This distinction might be missed. Maybe there will be a future developement***** in the language to re-instate this distinction.

Remember before I said "-ed" meant past tense in all environments. After about 80 years (all the population has changed) this will no longer be true. In one environment (the antecedent clause) "-ed" will mean, more or less, counterfactuality

..

.* Notice that in TEL as in English. “if” plus a verb in indicative mood produce a verb with future** meaning. This isn’t surprising as the main point of conditional sentences is to evaluate contingencies ... to make plans for the future.

.** Just to complicate things a little. We can say that there are two types of verb. Telic verbs and Stative verbs. Telic verbs are verbs where an outside observer would see something happening. “drink” is such a verb. Stative verbs are verbs where an outside observer would not see anything happening. “believe” is such a verb. “if” plus a telic verb in indicative mood produce a verb with future meaning. “if” plus a stative verb in indicative mood produce a verb with future meaning, however this future meaning stretches down to the present (time of speaking). It is this tense that is the most pertinant hence it is said … “if” plus a stative verb in indicative mood produce a verb with present tense meaning.

.*** To account for this you could imagine that the universe split at the time of the rite. Resulting in Universe 1 where Umara attended the rite and Universe 2 where Umara failed to attend the rite. But don't worry your head about this, I am not advovating the "multiverse theory". An alternative way is to look at thing is that there is only one Universe, and some times future contingencies discussed happen and sometimes they fail to happen. I am too lazy to dream up another contingency so I am going with the "multiverse" view. But it doesn't matter one way or the other ... this paper is about linguistics and not theoretical cosmology.

.****

.***** I am of course thinking of English using “if” + “pluperfect” to indicate “counterfactual past” … I am not so sure how to explain of this developement. If our TE language had a past perfect would the third conditional be formed at the same time as the second conditional or would it be a subsequent developement.

..

..... Assumptions I have made

..

4 constants that I picked

(a) Radius of the community is 4 km

(b) Speed of propogation of information is 1 km/hour

(c) Time that disinterest sets in is 16 hours

(d) A considered future conditional situation will actually materialize half the time.

..

3 things that I assumed

(a) The community area has uniform population density

(b) People are equally talkative 24 hours a day

(c) Disinterest is sudden instead of gradual

..

But all the above comes out in the wash. I like to talk about specifics to make my explanation more vivid. I of course played around with these constants to give me around 70% counter-factuality. As a native English speaker I feel that this percentage is about right.

..

..... How counterfactual

..

Now primary function of the English word "if" is to indicate contingecy. It's job is not to show counterfactuality, so it ranges over the entire counterfactuality range ... well nearly.

Below I have drawn 4 sketches graduated 0 => 100. This represents degree of counterfactuality. Around zero you have a event/state which is dead certain, around 100 you have something which will totally not happen.

"if" [bluish] is represented in the top sketch. You notice that it spans nearly the entire counterfactuality range. Only when something is held to be totally real or realizable does it disappear. In the extreme left of this continuum "if" would be replaced by "when" in English.

This division is not really necessary. The German particle "wenn" [pinkish] is shown in the second top sketch. As you see it covers the entire continuum.

The third sketch represents "if" + "past tense". Notice that it does not go all the way to the right. The explanation for this is the considerable amount of "unknown" that contributes to its meaning (remember the volume coloured yellow in U1 and U2 (U = Universe).

..

..

The bottom sketch represents the Slovenian particle "da". Slovenian also has the particle "bi" for expressing contingency. I presume 'bi" would have a distribution similar to "if" or "wenn" if it was sketched, but with it stopping about where '"da'" starts.

Because of the distribution of "if" + "past tense" (its RHS cut-off point in fact), to make sure a proposition is understood 100% as counterfactual you have to add a "tag" to the to an "if" + "past tense" conditional sentence. For example, to "if you left tomorrow, you would arrive on Tuesday" you would have to add the tag " ... but you can't leave tomorrow".

Also because of the distribution of "if" + "past tense" (its range quite far towards the LHS), it is possible to cancel* "if" + "past tense" conditional sentence. For example "If you had enough money, you could visit Australia", could be cancelled by adding "... well you have enough money, you can visit Australia". This sort of cancellation can not be used with "da" [the LHS of "da" would have to spread a lot further to the RHS to make it cancelable].

Various languages have such strong counterfactuals as Slovenian. For example mandarin has "yaobushi" as oppose to the normal contingence marker ruguo. Usually these strong counterfactuals have other functions in their language. I suspect the strong counterfactual meaning is the derived meaning (as "because" is the derived meaning of "since"). I would expect these strong counterfactuals to be more prevalent in languages with no past tense (maybe these WALS people could map "strong counterfactual" against "no past tense")

The strong counterfactuals in the various languages that possess them, may all have come about by different processes and hence all have slightly different ranges (an interesting topic for further research), however all the "if" + "past tense" languages should have a very similar counterfactuality range. [Note to self : is this right ? is there more complications?]

..

.*But this cancelation seems a bit awkward to me, is this because of a "logical" problem, or is it because the left hand edge of "if" + "past tense" is so far from zero : near the limit of "cancelability". I don't know.

..

..... Other considerations

..

There must be an explanation of why, if a language has an indicative/subjunctive distinction as well as a past/non-past distinction (i.e. a four-way split), it is inevitable that the "subjunctive + past" verb form is associated with counter-factuality (I suspect this is quite easy)

There also must be an explanation of why, if a language has a imperfective/perfective distinction as well as a past/non-past distinction (i.e. a four-way split), it is inevitable that the "imperfective + past" verb form is associated with counter-factuality (a bit more challenging). Perhaps it is the habitual meaning associated with the imperfective that is key here.

In English (and in other languages)

..

..... Other languages

..

Finnish and Swahili

..

I am interested to study a fair number of languages to find out what percentage of languages in general have a counter-factual derived by the same forces that shaped the English counter-factual.

As of this moment in time I have surveyed two ... Finnish and Swahili.

... Finnish

..

Finnish has 4 moods : indicative, imperative, conditional (COND) and potential.

It also has a past/non-past distinction however this distinction only arises in the indicative mood. For a conditional sentence the conditional marker isi must appear in both the antecedent and the consequent. For example ...

olisin iloinen, jos tulisit = "I would be pleased if you came" or "I will be pleased if you come"

..

| ol-isi-n | iloinen | jos | tul-isi-t |

|---|---|---|---|

| be-COND-1SG | pleased | if | come-COND-2SG |

..

... Swahili

..

The Swahili verb incorporates (at the least) a subject marker and tense/aspect marker. For example ...

nitakaa = I will stay

..

| ni-ta-kaa |

|---|

| 1SG-FUT-stay |

..

The total list of tense/aspect markers are ... -ta- = future : -li- = past : -na- = present : -a- = generic : -ki- = "when"/"as soon as" : -ka- = "and then" : hu- = habitual : -nge- = "if" : ngali = "if"/"counter-factual" ... (9 in all)

Quite an interesting list of concepts. Concepts that are outside what are usually considered tense/aspect. But look at ngali. I am sure that this is an amalgamation of -nge- plus -li-*. Also I read in my Swahili book " -nge- signifies hypothetical and ngali signifies counter-factual, but people are always getting them confused, as people do in English ". Mmmh ... to me this sounds like ngali means "around 70%" counter-factual". I suspect that the Swahili "counter-factual" has been forged by the exact same process that produced the English "counter-factual".

..

.* I would really like to discuss this with a bantu-ist sometime.

..

... Warlpiri

..

..... Other examples of semantic drift

..

Near the beginning we talked about "since" expanding its meaning. Here I would like to give other examples of semantic drift.

These examples don't really add to my proposition re counterfactuality. But I find this sort of thing delightful. Think of them as EXTRAS for no extra charge.

..

... After

..

How “after” changed from a particle expressing relative position to a particle expressing relative time.

This involves a fulcrum suit rather than a fulcrum situation.

Imagine situations …

a) the speaker is stationary being approached by two people, John and Mary. Mary is 30mtr behind John.

b) The speaker reporting on John and Mary leaving location L. Mary is 30mtr behind John.

c) The speaker reporting on John and Mary arriving at location L. Mary is 30mtr behind John.

With countless exposures to this senario “After John came Mary” came to have connotations of the future. “After John came Mary” came to be re-analyzed as “After John came, Mary came”.

In modern English “after” is almost exclusively about time. Its old positional meaning being now is expressed by “behind”. Although the old meaning still lingers in certain situations that involve position/time meaning at the same time. As in the verb “to run after”.

..

... Have

..

How “have” picked up an additional use.

In Western Europe over a thousand years ago, you would have a priest saying his prayers with his Rosary Beads. If interupted, he might say “I have 15 beads prayed (prayed = past participle). A farmer at that time might say “I have 5 fields ploughed (ploughed = past participle)[and two field not yet ploughed … for example]. “have” which originally meant only possession came to take on the connotation (alongwith the PP) of “the action is done and dusted”, “it has been done at least once” and “the state resulting from this action still exists at the present time”.

Interestingly this extention of the use of “have” happened quite suddenly. There was a re-analysis of the sentence. The adjective (past participle) was suddenly bracketed with “have” and considered the core of the predicate. I think oof this re-analysis a bit like these line drawings … at first glance you see an old woman looking down … on second glanse you see a young woman looking away into the distance.

This particular reanalysis happened all over Western Europe at the same time. Now at this time the Catholic Church was the only institution common to all Western Europe. Also monks and priest tied the whole area together by their frequent pilgrimages. Also at that time rosary beads were very popular … the midieval equivalent of the mobile phone? Could a cultural artefact been the point of origin for a major areal linguistic innovation? Far fetched ???

..

... While

..

... As

..

..... Post Script

..

I hope I have explained why (by way of typical human interaction) "past tense morphology" (by itself straight forward and unambiguous) plus "if" (by itself a pretty straight forward marker of conditional sentence) have come together. And together have a meaning "around 70% counter-factual".

I deliberately set my thought experiment in a pre-industrial age. Whether things like mobile phones and people zooming about in automobiles would affect the process described is an interesting question.

..