Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

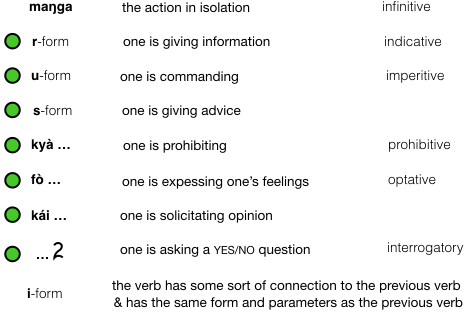

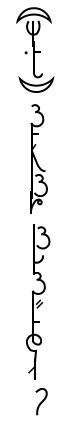

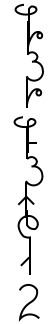

..... THE SEVEN MOODS

..

When people speak they have different intentions. That is they are trying to achieve different things by speaking ... maybe they are trying to convey information, or wanting somebody to do something, or not to do something, or they are just expressing their feelings about something. All these are examples of what is called moods. Different languages have different methods of coding their moods. Also the various moods of a languages cover a different semantic range compared to other languages.

There are 7 moods in béu ... 3 expressing themselves by changes to the root verb and 4 by periphrasis.

..

..

..

What are considered moods are shown by a green circle.

..

..

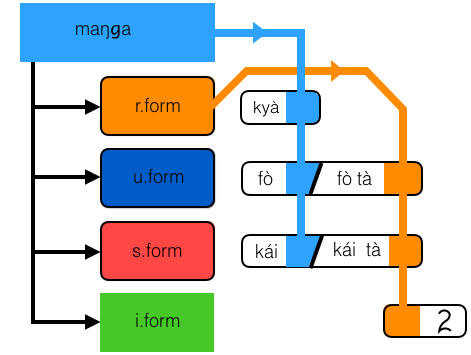

How the different moods and forms interact are shown above. [this will be explained in full later]

..

... Manga

..

This is the base form of the verb ... not considered a mood. maŋga corresponds to what is called the "infinitive" in some languages or the "masDar" in Arabic.

About 32% of multi syllable maŋga end in "a".

About 16% of multi syllable maŋga end in "e", and the same for "o".

About 9% of multi syllable maŋga end in "au", and the same for "oi", "eu" and "ai".

Note that no maŋga end in "i", "u", "ia" and "ua"

"i" is reserved for marking verb chains, which will be explained later.

"u" is used for the imperative mood ... i.e. for commanding people.

"ia" is used for a past passive participle. For example ...

yubako = to strengthen

yubakia = strengthened ... as in pazba dí r yubakia => "this table is strengthened"

"ua" could be called the future passive participle I guess. For example ...

ndi r yubakua => these ones must be strengthened

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk .... not to walk

..

... The indicative

..

Also called the R-form.

..

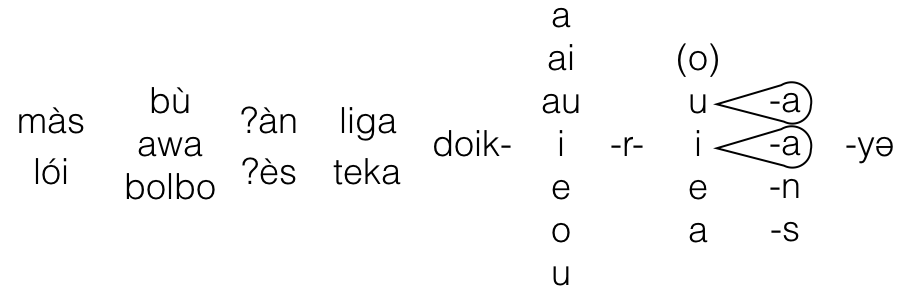

To make a verb in the indicative mood, you must first deleted the final vowel from the infinitive. Then add affixes that indicate "agent", "indicative mood", "tense", "evidentiality" and "perfectness". We will refer to these as slots 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 respectively.

..

.. Slot 1

..

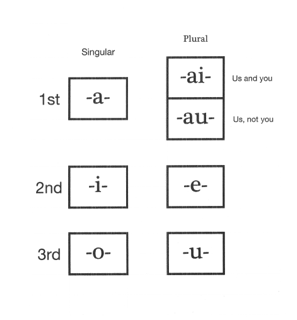

Slot 1 is for the agent ..

One of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer..

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikair and doikaur = we walk

doikir = you walk

doiker = you walk

doikor = he/she/it walks

doikur = they walk

..

.. Slot 2

..

Slot 2 is for the indicative mood marker.

..

At this point we must introduce a new sound and a new letter.

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in grammatical suffixes and it indicates the indicative mood.

If you hear an "r" you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

..

.. Slot 3

..

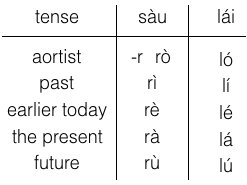

Slot 3 is for tense markers. There are 5 tense markers in béu

..

1) doikaro = I walk

This is the aortist tense ... the timeless tense. Used for generic statements, such as ... "birds fly".

Actually the final o is always dropped unless there is an n or an s in the evidentiality slot.

So *doikaro => doikar = I walk

2) doikaru = I will walk

This is the future tense

3) doikari = I walked

This is the past tense. This means that the action was done before today (by the way ... the béu day starts at 6 in the morning).

4) doikare = I walked

This is the near-past tense. This means that the action was done earlier on today (a good memory aid is to remember that e is the same vowel as in the English word "day")

5) doikara = I am walking

This is the present tense ... it means that the action is ongoing at the time of speaking.

..

It can be seen that béu is more fine-grained, tense-wise than most of the world's languages ... http://wals.info/chapter/66 and http://wals.info/chapter/67

..

.. Slot 4

..

Slot 4 is for the evidential markers (well three out of five are evidential markers)

..

There are three markers that cites on what evidence the speaker is saying what he is saying. However it is not mandatory to stipulate on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In fact most occurrences of the indicative verb do not have an evidence marker.

The markers are as follows ...

1) -n

For example ... doikorin = "I guess that he walked" ... That is the speaker worked it out from circumstances/clues observed.

2) -s

For example ... doikoris = "They say he walked" ....... That is the speaker was told by some third party(ies) or overheard some third party(ies) talking.

3) -a

For example ... doikria = "he walked, I saw him" ...... That is the speaker saw it with his own eyes.

Note that the above evidential only co-occurs with the past tense and near-past tense. Actually when used with the near-past tense, e.a => ia. Hence when this evidential is used, we loose the distinction between "past" and "near-past".

Now there is a forth possibility for this slot ... and it is not actually an evidintial. Furthermore it has the same form as 3).

4) -a

For example ... doikorua = "he intends to walk" ... the agent in this case, of course, must be a sentient being (i.e. human).

Note that the above only co-occurs with the future tense.

5) -ø

This is the null morpheme. If the speaker doesn't know the evidential or deems it unimportant, then the null morpheme is used. According to corpus studies in béu, 60% - 70% of indicative mood verbs have the null morpheme.

..

It can be seen that the béu evidentiality inventory is quite substantial compared to other languages ... http://wals.info/chapter/78

..

.. Slot 5

..

This slot can have the "perfect aspect marker" yə or not (you can call the second case the null morpheme choise ... if you want)

..

The perfect tense, logically doesn't differ that much difference from the past tense,. but it is emphasizing a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this aspect in English and it is realized as "have -en".

For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch, this emphasizes the absence of John as opposed to "he went for lunch". The latter is just an action that happened in the past, the former is a present state brought about by a past action.

For another example ... "she read the book on geometry"

This doesn't specify whether she read it all the way thru or whether she just read a bit of it. Whereas ...

"she has read the book on geometry", implies she read the book all the way thru, but more importantly the connotation is that at the present time she has knowledge of geometry.

..

The perfect marker -yə was probably derived from ìa "to finish/to complete" in its verb chain form. It has been suggested that it could have been derived from yái "to have/to possess" in its verb chain form but this is now considered very unlikely. The perfect aspect occurs in roughly half of the languages of the world ... http://wals.info/chapter/68

..

Also it appears that 5 categories being appended to the verb is typical of languages of the world. See ... http://wals.info/chapter/22 [If I have understood the chapter properly]

..

... The imperative

..

You use the following forms for giving orders ... for giving commands. When you use the following forms you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action ... although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible.

..

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

The final vowel of the maŋga is deleted and replaced with u.

doika = to walk

doiku = walk !

..

For monosyllabic verbs the base form by itself can be used for giving orders.

gàu = "to do"

gàu = "do it" ... often só is added fot extra emphasis.

só gàu = do it !

One verb has an irregular form.

jò = "to go"

ojo = "go" ... actually a bit abrupt, probably expressing exasperation, veering towards "fuck off" ... jò itself can be used as a very polite form.

..

The imperative cab be directed at second person singular or second person plural. When addressing a group and issuing a command to the entire group you sort of let your eyes flick over the entire group. When addressing a group and issuing a command to one person you keep your eyes on this person when issuing the command ... maybe saying their name before the command ... probably preseded by só which is a vocative marker as well as being an emphatic particle.

..

... The advisory

..

Also called the S-form.

..

There is a form similar to the R-form. However it only has two slots. The personal pronoun slot and A slot that has "s". Basically it is used for giving advice. The speaker is not upset if the hearer doesn't act (as he would be if it was a command) and he is not upset if he doesn't get feedback/advice/approval/disapproval (as he would be if it was a hortative). He is simply giving the listener some advice and the listener can chew it over at his leisure ... or he can completely disregard what is said ... up to him/her. The advice could be for the common good or the good of the listener (not realy for the good of the speaker ... unless the speaker and the listener identify together ... in which case we are talking about the common good). Maybe this form is equivalent to "should" in English.

..

solbis moze = You should drink some water

solbas moze = I should drink some water

solbos moze = He should drink some water

For mono-syllables an be- is prefixed as well ...

jò = to go

bejis nambon = You should go home

bejas nambon = I should go home

bejos mambon = She should go home.

..

I simply call this the S-form instead of making up a silly name.

..

The R-form when used with náu "to give" results in two forms ... benis and benes that when followed by tà play an important role in the grammar of béu

benis means "you allow" or "let" [benes being the form used when talking to more than one person]

benis tà nambon jàr = Let me go home

benis tà nambon jùar = Let us go home (not including you)

benis tà nambon jòr = Let him go home

benis tà nambon jùr = Let them go home

It is usually only used with one of the 4 third parties listed above.

In linguistic jargon the benis tà form would be called the "cohortative". So we have ...

..

... The prohibitive

..

This is also called the negative imperative. Semantically it is the opposite of the imperative. It is formed by putting the particle kyà before maŋga.

kyà doika = don't walk

That is pretty much all there is to say about it.

..

... The optative

..

This form expresses a wish or hope of the speaker ... but there is no appeal for the addressee to act. Also it is not really giving information as such. It is more about letting the speaker express his emotions [ maybe "ventative would be a suitable name for it :-) ]

The form is introduced by the particle fò. This particle has no other uses. It always comes utterance initial.

It expresses wishful thinking. For example ... fò pás blèu doika = "if only I could walk"

This form is used for curses and benedictions ... by frequency of usage the former outnumber the latter by about 10 to 1. For example ...

fò diablos ò ʔáu = "May the Devil take him"

There are some formula type expressions that are used in certain situations/ rituals that use this form.. For example xxx = "God save the king"

The most common use of fò is the greeting fò fales sàu gipi "may peace be upon you"

The verb form in this construction is usually maŋga. Most often hopes and wishes are for the future, but sometimes they are orientated towards the past (I suppose they should be called regrets in these cases). For example ...

"If only you had arrived yesterday"

In these cases the R-form is used after the particle tà.

"If only you had arrived yesterday" => fò tà diriyə jana

The table below shows the optative construction ... either with the particle fò plus maŋga OR with the particles fò tà plus the R-form.

..

... Soliciting opinion

..

We have come across kái before. In chapter 2.10 we saw that it was a question word meaning "what kind of". It normally follows a noun being an adjective. For example ...

báu kái = what type of man ?

ò r báu kái = what type of man is he ?

ò r deuta kái = what type of soldier is he ?

nendi kái = this is what type ?

But just as a normal adjective can be a copula complement, so can kái.

ò r kái = what type is he ?

nendi r kái = this is what type ?

ʃì r kái = what type of thing is it ?

However when you see kái utterance initial you know that it has a slightly different function : it is introducing the "soliciting opinion" mood. For example ...

kái wìa nyáu nambon jindi = How about we go home now ? OR Let's go home now.

Now ... as with the "optative", the "soliciting opinion" mood is usually orientated towards the future and uses maŋga. However their are circumstances where you solicit opinion about past events [for example a group of detectives on a crime scene discussing the possible steps taken by the perpetrator]. In these circumstances the R-form would be used preceded by the particle tà ... [see the table in the section above]

The main thing about this mood is that the speaker is asking for feedback/advice/approval or disapproval. But it overlaps with the field "gently suggesting a course of action" somewhat.

..

... The interrogative

..

Also called Polar Questions. A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

..

To turn a normal statement ( i.e. with the verb in its R-form) into a polar question the particle ʔai? is stuck on at the very end.

It has its own symbol (and I transcribe it as ʔai?) because it possesses its own tone contour.

I have mentioned this particle in chapter 1 (if you look back you can see its exact tone contour). Here is its symbol again ...

And here is an example of it in action ...

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

..

ʔai? is neutral as to the response expected ... well at least in positive questions.

To answer a positive question you answer ʔaiwa "yes" or aiya "no" (of course if "yes" or "no" are not adequate, you can digress ... the same as any language).

Here is an example of a positive question ...

glá r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman beautiful ?

If she is beautiful you answer ʔaiwa, if not you answer aiya*.

..

To answer a negative question it is not so simple. ʔaiwa and aiya are deemed insufficient to answer a negative question on their own. For example ...

glá bù r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman not beautiful ?

If she is not beautiful, you should answer bù hauʔe**, if she is you can answer either hù hauʔe or glá r hauʔe

I guess a negative question expects a negative answer, so a positive answer must be quite accoustically prominent (that is a short answer ("yes" or "no") is not enough)

..

We have mentioned só already ... in the above section about seŋko. This is the focus particle. It has a number of uses. When you want to emphasis one word in a clause, you would stick hù in front of it***.

Another use for só is when hailing somebody .... só jono = Hey Johnny

You can also stick it in front of someone's name when you are talking to them. However it is not a "vocative case" exactly. Well for one thing it is never mandatory. When used the speaker is gently chiding the listener : he is saying, something like ... the view you have is unique/unreasonable or the act you have done is unique/unreasonable. When I say unique I mean "only the listener" hold these views : the listener's views/actions are a bit strange.

When stuck in front of a non-multi-syllable verb you get an imperative. For example ... só nyáu = Go home

só can also be used to highlight one element is a statement or polar question. For example ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement ... bàus só glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.****

Unfocused question ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man give flowers to the woman ?

Focused statement ... bàus só glán nori alha ʔai? = It is to the woman that the man gave flowers ?

..

Any argument can be focused in this way.

..

*These words have a unique tone contour as well ... at least when spoken in isolation. I suppose I should have given these two words a symbol each ... if I wanted to be consistent.

**Mmm ... maybe you could answer ʔaiwa here ... but a bit unusual ... not entirely felicitous.

***In English, when you want to emphasis a word, you make it more accoustically prominent : you don't rush over it but give it a very careful articulation. This is iconic and I guess all languages do the same. It is a pity that there is no easy way to represent this in the English orthography apart from increasing the font size or adding exclamation marks.

****English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to an element in a clause.

..

The other type of question ... the content question was covered in the last chapter.

..

... The conflative

..

Also called the i-form. [By the way "conflative" is my term ... I thought I would join in the fun and make up a silly name myself]

I will only touch on this here. Nearer the end of this chapter there is a section that goes into this in a lot more detail. OK one quick example ...

to walk = doika

road = komwe

to follow = plèu

to whistle = wiza

From the above we could make three short sentences.

John walked => jono doikori

John followed the road => jonos komwe plori

John whistled => jono wizori

..

However as all three verbs seem to take part in the same action they can be combined. The first verb in the combination is normal (whether it is r-form, u-form, s-form or in fact manga).

The following verbs in the combination take a special ending ... -i for multi-syllable words and the schwa ə for mono-syllable words. So we get the form ...

John walked along the road whistling => jono doikori komwe plə wiʒi

..

... Other rubbish

A few languages use a hypothetical mood, which is used in sentences such as "you could have cut yourself", representing something that might have happened but did not.

"If you had done your homework, you wouldn't have failed the class", had done is an irrealis verb form.

..

..

Let me introduce three dependent clause types here ... the "when" clause, the reason clause and the purpose clause.

1) ... the "when" clause is intoduced by the particle kyù. For example ...

kyù twaru jene ʃì òn fyaru = When I see Jane I will tell her.

The English conditional particle "if"* is also translated as kyù

So ... "if I see Jane I will tell her" => kyù twaru jene ʃì òn fyaru also.

Now let's give the example sentence a habitual meaning ... say Jane fervantly supports Manchester United and the speaker always hears the latest results before Jane. So we have ...

kyù twár jene ʃì òn fyar = When I see Jane I will tell her.

*Other languages to conflate ? "when" and "if" are German (wenn) and Dutch (als). Actually if you really needed to disambiguate in béu you could use jindu meaning "as soon as" or fesʔa meaning "case"(as you can disambiguate in German, by using "sobald" and "falls")

* In English, there is another function for "if" ... it introduces a complement clause when the main clause verb is an "asking" verb. "whether" can also fulfill this function. The particle in béu that fulfills this function is wai.a. wai.a has only this function.

2) ... the reason clause is intoduced by the particle sài "because"

3) ... the "in order to" clause is intoduced by the particle gò "in order to"

XXXXXXX

As part of stand alone clauses

doikas = "should I walk" or "let me walk" or "how about me walking" or "can I walk" or "maybe I should walk"

doikis = "maybe you should walk" or "why don't you walk" or "how about you walking"

doikos = "let him walk"

doikos jono = "let John walk"

For transitive verbs ...

timpos baus waulo = let the man hit the dog

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding bù (or should that be jù). For example ...

bù doikos = best not to let him walk

They locked him up so that he would starve to death

They let him out at night so that he would not starve to death

The words kyò "show" and fyá "tell" follow the same pattern as 1) and 2) ... at least when the object is a noun and not a complement clause.

..

helga = life, helgai = alive, helgais = finite verb, helkas = a clause ( helkas <= helgaiskas ), swevan = a sentence

Lets take the solbe to explain these different forms. solbe is a maŋga and it would be found in the dictionary ... and if it was an English/ béu dictionary ... the translation "to drink" would lie alongside it.

An example of one of its (many) r.forms is solbori = He/she/it drank ....... so the r.form corresponds to a verb in indicative mood.

An example of one of its (handful of) s.forms is gò solban = I wish I could drink ....... corresponds to a sort of subjunctive mood.

..... The primary verb

..

If then the

A V2 that can take a thing.kas dead.kas sa.kas or takas as the naked noun.

1) ʔár wèu => I want a car

2) ʔár jó nambon => I want to go home

3) ʔár jís nambon => I want you to go home

4) ʔár tà gís timpiru ò => I want YOU to hit her/him

2) Is a very common construction ... the same subject for "want" and the second verb. The second verb is dead.

3) Different subjects for the two verbs ... not so common ... second verb is half-dead.

4) As the complement to ʔár gets more complicated there is more a tendency to use the tà construction.

Note that in béu there is no verb equivalent to "wish". You would use the construction ...

hà jau.e timpis ò = "if only you would hit him" to express this sentiment.

............

So in the above ... the construction as in 1) is used when the person doing the wanting, is also the subject (A or O) of the action required and the second action sort of "follows on" from the "wanting".

The construction as in 2) and 3) is used when the person doing the wanting is different from the subject (A or O) of the action required. The second action again sort of "following on" from the "wanting".

The construction as in 4) is used when the person doing the wanting is different from the subject (A or O) of the action required AND the second action DOES NOT "following on" from the "wanting".

..

..... Short verbs

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an R-form or an S-form verb is to delete the final vowel from the infinitive. However this is only applicable for multi-syllable words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different.

..

For a monosyllabic verbs the indicative endings and subjunctive suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive. For example ...

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ... swo.as = I should fear ... swo.is = you should fear ... swo.or = she should fear

..

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the R-form or an S-form. For example ...

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ... and so on

..

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the R-form or an S-form. For example ...

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ...ʔawir = you take ... and so on

..

..... To be, to become & to exist

..

There are two copula's ... sàu "to be" and lái "to become".

The three components of a copular clause have a strict order ... "copular subject" then "copula" then "copula complement" ... the same order as English in fact.

The copula subject is always unmarked.

..

However the indicative mood is not derived from the infinitive by the usual method. As you might remember the first 3 slots are mandory in the indicative form (the aortist tense being a null morpheme).

But for sàu and lái things are radically different. Below are the indicative forms for sàu and lái.

..

..

Note that the third column (under lái) are grammatically all R-form's ... even though they don't actually have any rhotic sound.

For sàu in the aortist tense, r is the complete copula. It is a clitic attached the the last vowel of the copula subject (however it is always written as a seperate word). For example ....

tomo r tumu = Thomas is stupid

It takes the tone of the copula subject (if the copula subject has one).

If the copula subject ends in a consonant then rò is used. For example ....

géus rò solki = the green one is smoothe

Evidentials can be added as normal to these forms. For example ...

jene gáu rìs hauʔe = "They say old Jane used to be beautiful"

jono jutu lón gáu = "I guess big John is becoming old" ... note that lón is considered mote appropriate than lán. If the timeframe of the action was a lot shorter then lá would be considered appropriate.

..

It is only the R-forms of the copula's which are irregular. All other forms are perfectly normal.

sàu bòi = "Be good" ................................................................. U-form

jono jutu bezos wistige = Big John should be more careful ...... S-form

?? ................................................................................................... I-form

[ jono jutu lós gáu = "They say big John is becoming old" : jono jutu belos gáu = big John should become old" ... if the S-form did not have the be- these two would have the same form ]

..

Note that for copular clauses, the subject noun or pronoun can never be dropped, because the person/number information is gone (that is ... there is no component to the left of the "r"). For a normal verb ... if the subject is 1st or 2nd person ... then the pronoun is invariably dropped. For 3rd person, whether you have a proper noun, pronoun or nothing depends upon discourse factors.

wài r wikai tè nù r yubau = "we are weak but they are strong"

ʃì r helkia = "it is broken" [ ʃì hulki ]

..

Often the O argument of a 2P verb is dropped if it is considered too trivial be to worth bothering about. For example solbe (to drink) is a transitive verb but often the O argument can be unceremoniously dropped. The copula subject in certain situations is also dropped. These situations largely correspond to when English uses "it" as a dummy subject. The reason for dropping the copula subject is almost the mirror image to the reason forvdropping an O argument. Whereas the O argument is thought too "trivial" or "predictable" the dropped copula subject is thought to be "all encompassing" or "so obvious that there is no need to mention it".

In these situations ... sòr is used. Notice that sòr is what the 3SG indicative form sàu would be if sàu was conjugated like a regular verb.

As with English, this construction is often used for the weather ...

fona = rain : fonia = rainy/raining : fonua = dry (well not raining). So ...

sòr fonia = it's raining

..

We have already seen the S-form of the verb ... used for giving advice (to 2nd person), or opining on a favourable course of action (about 3rd person), or commenting on possible courses of action (1st person). But it is possible to show finer shades of meaning by using a clause starting with sòr and containing tà plus one of the adjectives neʒi, boʒi or fàin.

..

neʒi = necessary

boʒi = best

fàin = fitting/appropriate

..

| sòr | neʒi | tà | ny-e-r-u | jindi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "it is" | necessary | CMPZ | return-2PL-IND-FUT | now |

==> It is necessary that you (pl) will return to home now ==> You (pl) must go home right now

| bù | sòr | fàin | tà | sw-a-r-u | ifan | jindi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEG | "it is" | appropriate | CMPZ | speak-1SG-IND-FUT | anything | now |

==> It is inappropriate that I will say anything now ==> I shouldn't say anything now

| sor-u | boʒi | tà | jubu | j-u-r-u |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "it is"-FUT | optimum | CMPZ | nobody | go-3PL-IND-FUT |

==> It will be best if nobody goes

..

OK ... sàu and lái are the two béu copula's.

There is another verb, that while not a copula, can function in a way similar to sòr. While sòr connects an attribute ( adjective ) to the universe at large (well at least attaces an attribute to the local environment) yór connects a noun to the universe at large. yór is actually the 3SG indicative form of the verb yái "to have on you". Now while sòr is never used in any other position apart from the sentence initial position, yór has other uses. For example ...

jonos yór kli.o = John has a knike

But when occurring without a subject ... yór takes on its special role ... it becomes an "existential verb". For example ...

yór dèus = "there is a God" or "God exists"

This construction can be negated in two ways ...

bù yór dèus = "there isn't a God" : yór jù dèus = "there is no God"

As indeed the English existential construction can.

Often this construction has a location incorporated into it. For example ...

yore yiŋki hè tunheuʔe yildos = "there were many attractive girls at the townhall this morning"

The above means pretty much the same as the transitive clause with the possessive verb ...

tunheus yore yiŋki hè yildos = "the townhall had many attractive girls this morning"

Which in turn means pretty much the same as the copula sentence ...

yiŋki hè rè tunheuʔe yildos = "many attractive girls were at the townhall this morning"

So three ways to say the same thing.

But note ...

*tunheuʔe rè yiŋki hè yildos = "at the townhall this morning were many attractive girls"

The above construction that is allowed in English is not allowed in béu

fàin ....... the action will be approved of by society at large (or at least the subsection society that is interested in the matter).

boʒi ...... the action will yield more benefits than other actions (or no action at all).

neʒi ..... the action is a vital part of some larger scheme that will achieve some goal.

Note ... neʒi = "necessary" => neʒis = a necessity : boʒi = "best" => boʒis = the optimum

..

..... Special short verbs

..

The above is the general rules for short verbs, however the 37 short verbs below the rules are different.

Their vowels of the infinitive are completely deleted for the indicative and subjunctive verb forms. For example ...

pòr nambo = he enters the house ... not *poi.or nambo

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to store | ||

| yái = to have | |||

| jò = to go | jwòi = to to pass through, undergo, to bear, to endure, to stand | ||

| féu = to exit | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

| bái = to rise | byó = to own | blèu = to hold | bwí = to see |

| gàu = to do | glù = to know | gwói = to pass by | |

| día = to arrive / reach | dwài = to pursue | ||

| lái = to become | |||

| cùa = to leave / depart | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slòi = to flow | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kàu = to fall | kyò = to use | klói = to like | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyá = to fly | plèu = to follow | |

| té = to come | twá = to meet | ||

| wè = to think | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to learn |

lái = to become || : slái = to change ..... note conflation with "to flow" when in the indicative form.

danau = to place

Some nouns related to the above ... yaifan = possessions, property, flofan = food, gaufan = products, myefan = reserves, naufan = tax, tribute,

gàus = a task, a thing that must be done, gàis = a deed, a thing that have been done, gò = behavior.

A particle related to the above ... yó ... a particle that indicates possession, occurs after the "possessed" and before the "possessor.

..

..... A SECOND VOICE

According to WALS [ http://wals.info/chapter/107 ] 56 % of the world languages manage without a passive.

The reasons for having a passive have been described as ... Many languages have both an active and a passive voice; this allows for greater flexibility in sentence construction, as either the semantic agent or patient may take the syntactic role of subject. The use of passive voice allows speakers to organize stretches of discourse by placing figures other than the agent in subject position. This may be done to foreground the patient, recipient, or other thematic role; it may also be useful when the semantic patient is the topic of on-going discussion. The passive voice may also be used to avoid specifying the agent of an action.

I have decided to follow the majority of the world languages and not have a passive. [ actually there are varying degrees and types of what can be called "passive". Linguists have reached a concensus on 4 or 5 points (see the above link) that must be fullfilled for a construction to be called a passive. These 4 or 5 points I feel are a bit arbitary. In fact I find many facets of cannonical passives a bit "fiddly".

béu gets by with a sort pseudo passive and its passive participle ....

jonos hài toili kludori => John wrote many books

hài toili kluduri => many books were written .... when u is placed in verbal slot 1 and no agent is mentioned ... then this can be translated into English by the passive. [ u is considered more generic than the singular o ]

However when a suitable agent is around, floating about in the consciousness of the interlocutors, not mentioned in the actual clause but of high topicicality, active in that part of the brain which prossesses speach ... this shouldn't be translated using the passive.

For example ... if the previous clause was kludomau.a dè r sowe jini "those authors are very clever" .... then hài toili kluduri => they wrote many books

The use of u passive does imply human agents.

So ... "the computer is broken" would not be rendered by a u passive in béu because usually people do not deliberately break computers.

Rather "the computer is broken" => kyono r helkia where helkia is the passive participle of helka "to break".

The passive participle can only be used on two place verbs ... and makes most sense when the verb is more or less instantaneous and irrevocably changes the state of the object.

"the computer was broken by John" => jonos helkori kyono or kyono r helkia_jonos gori ... [the last being a two clause construction]

So I have demonstrated above how béu would translate a few situations where English would use a passive constuction. It is found that lack of a "real" passive does not break up the flow of béu discourse to any appreciatable extent. Also the use of the words ebu "somebody" and efan "something" make a lot of things possible.

..

The above leads us on to consider who or what is responsibly for an action ...

Consider geuko = "to turn green" ... which is a two place verb. (what I call a transitive verb)

1) báu lí gèu = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of gèu and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

Agent => Anything and the action could be accidental.

2) báu geukuri = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

Agent => Human and the action deliberate

3) báus tí geukori = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved and definitely a deliberate action.

Agent => Human and the action deliberate

..

Now consider mapa = "to close" ... a two place verb.

1) pintu lí mapia = the door became closed = the door closed

Agent => Anything ... It could be that the agent was the wind ... or even some fairy cái ... use your imagination.

2) pintu mapuri = the door was opened

Agent => Human and the action deliberate ... It strongly implies that the agent was human but is either unknown or unimportant.

Note ... there is no (3) here as a door is non-human.

..

In either of the (1)'s wistia "deliberately" or wistua "accidently" can be added after* lí. This automatically makes Agent => Human

The same for the (2)'s, but the incidence of wistua should greatly excede the incidence of wistia as "intention" is the default for this construction.

With (3) the connotation of intent is so strong that wistia/ wistua could be considered a bit infelicitous ... not impossible but indicative of a very unusual situation.

* or wistiwe' or wistuwe if not immediately after the verb. [by the way ... wisto = mind/brain]

..

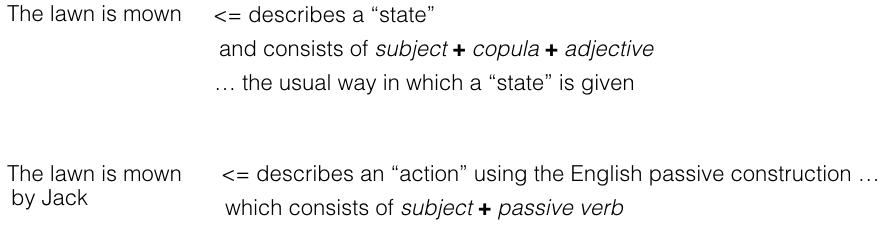

A discussion about the English passive construction [purely for amusement : nothing to do with béu]

..

..

Now you way wonder why I specified the second construction as 'subject' + 'passive verb' ... why not 'subject' + 'copula' + 'adjective' as in the first case.

Well there can be a difference in meaning between the two sentences. Suppose the lawn is habitually "mown" (albeit at longish intervals) by Jack. Then the second sentence tells us nothing about the present state of the lawn ... it could be quite overgrown. Now look at the first sentence ... imagine it has the same meaning as the second sentence but we were too lazy to mention the agent.

Can you see "an overgrown lawn" ... then think back to the first sentence when you first encountered it. Can you see see a "neat lawn". And then take in the meaning of the second sentence again and look back at the first. Can you see the "overgrown lawn" again. It is a bit like looking at one of these optical illusion ...

..

..

Now "mow" is a dynanic verb ... if you dwell on the concept you can see action, you can see people doing things. However "mown" is basically an adjective ... hence "is mown" (what I call a passive verb) is a "static verb". It has none of the movement associated with "mow". However we can resurrect this movement by using a "change of state" copula instead of the "static" copula. For example ...

..

Someone mows the lawn ..... active voice ......... dymamic

"The lawn is mown" ............. passive voice ....... static situation

"The lawn gets mown" ......... passive voice ....... dynamic situation

..

..... Six causative constructions

..

béu is a bit unusual in that it has no morphological means to make a causative. A good example of a morphological causative is from Japanese ...

==> Kanako made Ziro goKanako ga Ziroo o ik-ase-ta Kanako NOM Ziro ACC go-CAUS-PAST

You can see that the bit that makes this a causative "ase" has got lodged in the verb.

[ Note on terminology ... we will call Kanako the "causer" and we will call Ziro the "causee" ]

..

But maybe to say that béu has no morphological causatives is untrue. It has the following nine verb pairs ...

..

| pòi | to enter, to join | poinau | to put in |

| féu | to exit, to leave | feunau | to take out |

| bwí | to see | bwinau | to show |

| glù | to know | glunau | to inform ............. Note : fya means "to tell", basically the same thing but less formal ............................... |

| pyà | to fly | pyanau | to throw |

| jó | to go | jonau | to send |

| tè | to come | tenau | to summon |

| bái | to rise | bainau | to raise |

| kàu | to fall | kaunau | to lower |

| flò | to eat | flonau | to feed |

Above the centre line we have || => ||| : below | => ||

..

Now it is well known that the processes involved in the making a morphological causative are rarely completely productive. So maybe béu with its 10 derived verbs is not such an outlier after all.

But apart from these nine verbs (which arguably show a morphological causative) béu uses what are called periphrastic means to express a causative. These are ...

..

(a) gari solbe moze jenen = I made Jane drink water

(b) gari tà jenes solbori moze = I had Jane drink water

(c) tumari solbe moze jenen = I made Jane drink water

(d) tumari tà jenes solbori moze = I had Jane drink water

(e) nari solbe moze jenen = I let Jane drink water

(f) nari tà jenes solbori moze = I allowed Jane to drink water

..

The causer is the new argument in a causative expression that causes the action to be done.

The causee is the argument that actually does the action in a causativized sentence.

..

In (a) and (b) the verb gàu = "to do" or "to make" is used.

In (c) and (d) the verb tumai is used. This verb has no other use apart from making this type of causative construction.

In (e) and (f) the verb náu = "to give" is used.

..

Notice that in (a), (c) and (e) the maŋga must occur immediately after gàu, tumai or náu. This is the same as the French, Italian or Spanish causative constuction. For example ...

==> I will make Jean eat the cakesje ferai manger les gâteaux à Jean 1sgA make+fut+1sg eat+inf the cakes prep Jean

In the above table, it can be seen that there are 6 causative constructions. There are 3 degrees of "volition" (the willingness of the causee) and 2 degrees of "directness" (did the causer act directly on the causee or through intermidiaries).

..

Also notice that in (a), (c) and (e) the original subject is put in the dative case. In béu this is always the case ... whether the verb is intransitive, transitive or diitransitive (if the verb is ditransitive then this means the causative construction will have two datives ... a cause of confusion ? ... not really ... the original subject will be the latter of the two datives)

(a), (c) and (e) have what is called a compound causative verb. (i.e. one clause)

(b), (d) and (f) are what are called periphrastic causative constructions. (i.e. two clauses)

..

gari timpa jene jonon = I made John hit Jane

gari timpa glá òn = I made him/her hit the woman

To allow someone to do something.

..

If John was feeling a bit sick ... the teacher would say to him ...

"I give to you to go home now" => gìn nár nyáu nambon jindi

..

| gì-n | n-á-r | nyáu | nambo-n | jindi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2SG-DAT | give-1SG-IND | return.INF | house-DAT | now |

..

Now náu "to give" is a strange word. It is never put in the passive. Instead the word mài "to receive/get" is used.

So when John gets home he says to his mother ...

"I get to return home early by teacher" => mare nyáu nambon early hí teacher *

..

| m-a-r-e | nyáu | nambo-n | "early" | hí | "teacher" |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| receive-1SG-IND-PST | return.INF | house-DAT | early | by | teacher |

..

Note ... the particle hí is not used for anything else. So you come across it when you see jwè + maŋga or mài + maŋga ... well you might. Specifying the agent is not mandatory.

..

*Of course alternatively he could have used the direct voice and have said ... "teacher give to me to go home early"

..

More on the give/receive construction

..

náu = "to give" or "to allow" / "to let".

mài = "to receive" / "to get"

..

1) jonos noryə toili jenen = John has given a book to Jane

2) jonos norye jene toilitu = John has given Jane a book

3) jenes moryə toili (hí jono) = Jane has received a book (from John)

..

The same action but from two different perspectives.

Note that examples 1) and 2) mean exactly the same thing. But different pairs of pilana are used. So you always have a choice with the "give" construction ... well when the thing given is tangible and not maŋga.

..

About the optical illusion. Maybe you initially see a young woman glancing away ... then the semicircle + dot near the centre is an ear.

Or maybe you initially saw an older woman looking this way ... then the semicircle + dot near the centre is an eye.

(pás) gari tá (ò) donor = I made him/her walk

Is the below OK ?

mari náu jò = I received permission to go = I received to give to go.

jene nawori doika = "Jane has been made to walk" ??? OR "Jane has been allowed to walk"

jene jwore gàu doika = "Jane has been made to walk"

jene more (gò) doika = "Jane has been allowed to walk"

(pà) jwari gàu solbe moze (hí jono) = I was made to drink the water (by John)

moze jwore solbe (hí jene) = The water has been drunk (by Jane)

(John has let Jane go => jonos nori gò jene jò ... old thoughts ??? )

..... The reciprocal construction

..

The reciprocal particle is bèn

jonos jenes timpur bèn = "John and Jane are hitting each other" = "John and Jane hit one and other"

Note ... lè "and" is not used when two nouns in the ergative case occur adjacent to each other.

The particle also comes after adjectives occasionally. For example ...

jono lè jene r ʔài bèn = John and Jane are the same.

No real reason why it should be added to the above sentence ... except that it is judged to sound good.

ʔáu bèn "to take mutually" is the béu expression meaning ... do the dirty deed, have relations, roger, root, shag, boink, slam the clam, thump thighs, pass the gravy, wet the willy, make the beast with two backs ... make love.

..

..... 4 slots before the verb

..

We have already covered the indicative with the 4 slots for "agent", "tense/aspect", " r " and "evidentiality" at the end of the denuded infinitive. As well as the nuances given by these post verbal slots, there are a set of nine particles which give further nuances to the basic indicative verb. These are called (near-standers ?). These particles occur in 4 pre-verbal slots. However these particles are independent word, not affixes.

These are shown (along with the 4 post-verbal slots) below ...

... Slot 1

..

These two particles indicate probability.

màs = possibly

lói = probably

Of course they cover a wide probability range but the average probability gleaned from hearing màs would probably be around 50 %, and for lói, maybe up near 90 %.

..

... Slot 2

..

bù is a negative particle which has scope over the entire sentence ... equivalent to "not" in English.

awa gives a "habitual but irregular" (maybe best translated as "now and again" or "occasionally" or even "not usually") meaning to the main verb. Possibly related to the verb awata ? which means "to wander".

bolbo gives a "habitual and regular" (best translated as "normally" or "usually" or "regularly") meaning to the main verb. Possibly related to the verb bolboi which means "to roll".

OK ... but if you are only allowed one of these five, how would you translate .. "I don't usually come to these parent-teacher meetings but ...."

Well you wont say ... awa tár to these parent-teacher nò twás _ ...."

..

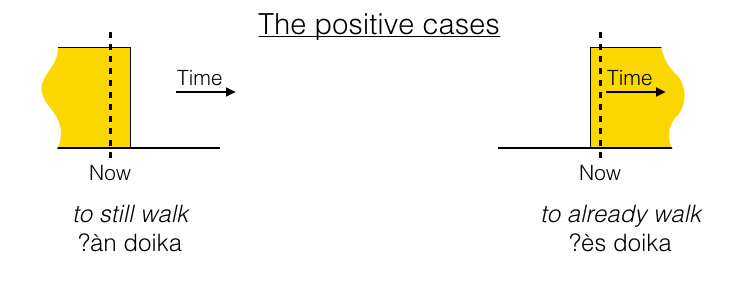

... Slot 3

..

These are called aspectual operators or aspectual particles.

..

In English the nearest translations* are ʔàn = "still" and ʔès = "already".

Many many languages have equivalents to these two particles. For example ...

..

| English | still | already |

| German | noch | schon |

| béu | ʔàn | ʔès |

| French | encore | déjà |

| Mandarin | hái | yîjing |

| Dutch | nog | al |

| Russian | eščë | uže |

| Serbo-Croatian | još | već |

| Finnish | vielä | jo |

| Swedish | än(nu) | redan |

| Indonesian | masih | sudah |

..

ʔàn indicates ...

1) an activity is ongoing

2) the activity must stop some time in the future, possibly quite soon.

3) there is a certain expectation* that the activity should have stopped by now.

Possibly related to the verb ʔanto which means "to continue".

ʔès indicates ...

1) an activity is ongoing

2) the activity was not ongoing some time in the past, possibly quite recently.

3) there is a certain expectation** that the activity should not have started yet.

Possibly related to the verb ʔesto which means "to start".

..

A very interesting thing about these two words is their negation. Either the particle plus verb can be negated (shown by one bar above the two word) or the verb by itself can be negated (shown by a bar above the verb).

If the verb is negated ... then, on the diagram ... the yellow place becomes white and the white space becomes yellow.

If the particle plus verb is negated ... then, on the diagram ... the dashed line representing now, is translated to the other side of the barrier that represents onset/cessation of activity.

..

..

As you see by above ... by changing whether the negator act on the verb plus the operator or whether the operator acts on the negator plus the verb, negative sentenced with ʔàn and ʔès give diametrically opposite meanings*** (the proper technical term is to call them "dual operators").

Note that there are 4 possible negative cases to choose from and a language only needs 2. I guess a language (to cover all negative cases) should have either "(a) and (c)" or "(b) and (d)" or "(a) and (b)" or "(c) and (d)".

For example, all Slavic languages prefer verb negation, hence they tend to have (c) and (d). In German, only (a) and (c) are allowed in positive declarations. Nahuatl has negation of the operator so uses (a) and (b). It can be said that English is an a/b language also. However in the negative English uses suppletive forms for the two operators ... "yet" for "already" and "anymore" for "still" ... hence "not yet" and "not anymore".

In béu, bù negates the whole sentence**** (or maybe I should say ... the whole clause). So béu is an a/b language as well.

..

* However the English pattern is a bit irregular in that it has the particle "yet" which corresponds to ʔàn in some circumstances and to ʔès in other circumstances.

** I believe that this expectation is a connotation that will inevitable develop if you have prolonged usage of a particle with meaning 1 and 2.

*** I find this stuff very interesting. If you want to know more, read "The Meaning of Focus Particles" by Ekkehard König.

**** In béu the particle jù negates one element in a sentence (the element immediately following it). So instead of using (a) and (b) we might have had (c) and (d) in the form ... *?àn jù doika and *?ès jù doika.

..... A speaker of béu ... while recognizing the logic of *?àn jù doika and *?ès jù doika, would deem them ungrammatical.

..

... Slot 4

..

liga makes verbs which in themselves are quite compact timewise, more spread out. For example ...

..

| koʕia | to cough | liga koʕia | "to be coughing", "to have a coughing fit" |

| timpa | to hit | liga timpa | "to be hitting" or "to assault" |

..

liga is never used with verbs that typically have an inherent long time duration. For example ...

- liga glarua beuba kewe would be translated as "I intend to be knowing the language of béu well" ... Not really good English either.

lglarua beuba kewe = "I intend to know the language of béu well" ... is more felicitous in both languages.

..

liga gives an imperative slant to the main verb. Possibly related to the verb ligai which means "to stay" or "to lie". Now in the very best register of béu this particle is used for a certain poetic effect, it is used sparingly and is not necessary for understanding what is being said. However people that are L1 speakers of a language having a perfective/imperfective tend to over-use liga. This is not really a problem, it just shows that they are not L1 béu speakers. Conversely people that are L1 speakers of language that lacks this distinction tend to not use liga enough. Again ... no real problem.

..

teka is the opposite of liga. It means "momentarily". Possibly related to the verb telka which means "to slip a little bit". While in theory it can be used with almost any verb, it tends to be used disproportionately with a dozen or so verbs. For example ...

..

| bwí | to see | teka bwí | to catch a glimpse |

| wòi | to think | teka wòi | to think for a moment |

| ʕái | to want | teka ʕái | for a moment, to want |

..

... Restrictions

..

..

Certain members of slots 1,2 and 3 can only co-occur with a subset of the affixes in post-verbal slots 3 and 4.

YELLOW ... if you have màs or lói then in post-verbal slot 4 you can only have the -a that follows the future tense u (that is, the one that isn't really an evidential). However all affixes in slot 4 are not compulsary.

GREEN ... if you have awa or bolbo then in post-verbal slot 3 you can only have the aortist tense (the one that is the null affix).

RED ... if you have ʔàn or ʔès then in post-verbal slot 3 you can only have the present, future and past tenses.

BLUE ... we introduce another particle here ... juku meaning "never". It is a more emphatic negative than bù, but can only be used with the 3 perfect aspects in slot 3.

..

Most of the above restrictions don't need much comment. Hoewver in English there appears to be some conflation between "already" and the perfect aspect. For example "I've done it already". Maybe the reduced phonological prominence of the aspectual marker (i.e. "v") is a major contributing factor of this conflation. In béu ʔès and the three perfect aspectual markers are two different things.

1) When you use ʔès (or ʔàn) you are concerned about the onset/cessation of an event ... probably in the recent past or near future.

2) When you use the perfect aspect you are concerned about the state of the subject (A or S) which has resulted from some event that might be quite far in the past ... impinging on this is a stong "experential" connotation. For example ... if John has read a book on geometry, you can assume he has some knowledge of this subject. If he has been to London, you can assume he has many sounds and sights of London stored away in his memory.

..

Not to be confused with lò = "other" and kyulo = "again" These two particles come just in front of the verb. They are only used with the indicative verb and the maŋga.

..

..... Tying two clauses together

..

In béu we have live clauses and dead clause.

The head of a live clause is a verb in its declarative form.

The head of a dead clause is a verb in its declarative form.

A live clause has its main elements in any order, the S term is marked as the ergative. The A and O terms are unmarked.

A dead clause has word order VS or VAO, the O term being marked as the dative. The A and S terms are unmarked.

tàin = before

jáus = after

ʔéu = while, as

í kyù = until => iyu

fì kyù = ever since => fiyu

If the subjects (that is S or A) of two clauses are different then they can be conjoined timewise by using one of the above stand-alone particles. For example ...

1) jenes bwori jono ʔéu jonos fori nambo tí = Jane saw John as he was leaving his house.

Also ... as in English we can have the two clauses in the other order ...

2) ʔéu jonos fori nambo tí_jenes bwori ò = As John was leaving his house, Jane saw him

Notice that in this sentence, the second jono has been replaced by the pronoun ò ... in actual fact ... in 1) the chances are that jonos would be replaced by ós ... but this makes the sentence ambiguous.

John whistled as he left his house = jono wizori ʔéu ò fori nambo tí = *jono wizori ʔéu féu í nambo tí

---

Now if the subjects of two clauses are the same, one of the clauses can becomes a dead clause. Only a very short and simple clause can become a dead clause ... both ...

A) Any time,place or manner adjuncts will stop a clause collapsing to a dead clause.

B) An O argument that is longer than a single word.

When the above requirements are met ....

A) S or A is dropped completely.

B) The linker word is appended to the infinitive.

C) if there is an O it immediately follows the infinitive and has the dative marker -n affixed.

1) S while S ................... jono wizori ʔéu ò huzori ... (pronoun used in second clause)

=>jono wizori huzuaʔeu = John whistled while smoking ... (must drop S, the linker must be appended to the infinitive)

2) A O while A O ..... jonos timpori jene ʔéu ós huzori ʃiga ... (pronoun used in second clause)

=> jonos timpori jene huzuaʔeu ʃigan ... (must drop A, the linker must be appended to the infinitive. O must be a single word)

3) A O while S .......... jonos timpori jene ʔéu ò huzori ... (pronoun used in second clause)

=> jonos timpori jene huzuaʔeu ... (must drop S, the linker must be appended to the infinitive)

4) S while A O ........... jono huzori ʔéu ós timpori jene .... (pronoun used in second clause)

=> jono huzori timpaʔeu jenen .... (must drop A, the linker must be appended to the infinitive. O must be a single word)

John left his house whistling = Jonos fori nambo tí ʔéu wiʒia

wiʒia = to whistle

koʔia = to cough

huzua = to smoke

..

... Introducing Verb Chains

..

béu has a technique that integrates two clauses even further. It is called the "verb chain".

In certain situations it is considered unnecessary to include person-tense information on an active verb. If there are a number of verb concepts that can be thought of as partaking in sort of "composite" activity, then only the initial verb gets person-tense-evidentiality information. The non-initial verbs have the final verb of their base form deleted and the vowel i added. For example ... slanje (to cook) => slanji. If the verb only has one syllable, then the final verb of their base form (the only vowel) is replaced with a schwa and the word looses its tone. For example ... flò (to eat) => flə.

Below are three verb chains ... each one having a different time structure.

..

... Similtaneous Time

..

John walked along the road whistling => jono doikori komwe plə wiʒi*

..

to whistle = wiza

to walk = doika

to follow = plèu

road = komwe

..

We can also say ...

"John walked along the road whistling" => jonos komwe plori doiki wiʒi.

In fact there are six ways in which the three verbs can be arranged. The meaning of the sentence would be exactly the same in all six cases.

Note that "John" appears "naked" or in his "s-marked" form depending on whether the first verb is transitive or intransitive. The first verb has the full verb train ( it is "r-form" however later verbs in the chain are in their reduced form (i.e. their "i-form")

*Actually this sentence is more likely to be expressed as jono doikori komwewo wiʒi

..

... Interleaved Time

..

All afternoon I was writing reports and answering the telephone => falaja ú kludari fyakas sweno nyauʒi

..

afternoon = falaja

to write = kludau

report(noun) = fyakas

telephone(noun) = sweno

to answer = nyauze

..

Note .... in the first example the times of the different verbs were similtaneous, in this example the times of the different verbs are randomly interleaved throughout the afternoon.

It would also be possible to render the above as falaja ú sweno nyauzari kludi fyakas ... means the same thing.

Notice that in this example we have two verb-object-pairs, (kludau, fyakas) and (sweno, nyauze). While an object must stay next to its verb, there is a tendency for it to precede the verb when it is definite and to follow it when indefinite).

[ And with a change of tense ... "All afternoon I have been writing reports and answering the telephone" => falaja ú kludar fyakas sweno nyauʒi ]

..

... Sequential Time

..

Yesterday John caught, cooked and ate three fish => jana jonos holdori slanji flə léu fiʒi

..

yesterday = jana

to catch = holda

three = léu

fish = fiʒi

..

In this example, the three verb concepts happened in a definite order, and must be expressed in that order.

A verb chain must be contained in one clause. However the verb form used in a verb chain (the i-form ... both slanji and flə are considered the i-forms of the verbs slanje and flò ... even though there is no "i" in the form flə) can be used over multiple clauses. For example ...

"Yesterday John caught three fish, then cooked then and then ate them" => jana jonos holdori léu fiʒi _ slanji _ flə .... actually, is this a good idea (i-form over multiple clauses) ???

You can continue adding "i-form" verbs indefinitely. However if the subject changes, you have to go back to an "r-form". Also if the internal time structure of the composite action was to change, then one must revert to an "r-form". jana jonos holdori léu fiʒi _ slanji _ flə is definitely three clauses because of the mandatory intonation breaks. The object of the last two clauses is the same as the object of the first clause. However this need not be the case ( I can not think of a good example at the moment ??? ).

[ Note ... Although the verb chain is the common way to express when two actions happen at the same time, another method is possible. That is to make one of the verbs into an adjective. And then by placing this directly behind another verb you get an adverb. For example ... wizari doikala = I whistled while I walked] .... ???

Note that in these three examples, that the internal time structure of the composite action (i.e. simultaneous, interleaved and sequential) are never formally stated. Rather they are known due to the listeners knowledge of the situation being described.

The internal time structure of a situation is not always clear. But if it is thought necessary to clarify it one can always fall back to conjoining clauses with conjunctions.

..

... Motion Verb Chains

..

Verb chains are used a lot for verbs of motion. In certain languages (for example Cantonese, verbs do the job that prepositions do in European languages. Now béu does have a set of prepositions (the pilana). So for defining exactly what non-core NP's are doing in a sentence (that is everything that is not S, A or O) ... in béu this task is shared about equally between prepositions and minor verbs.

The rules are the same as stated in the previous section.

Now as you would expect, there are preferred orders. The diagram below shows the order that would probably be used for a future tense situation. Also this order would be preferred if someone was narrating a story and wanted to keep everything in sequence. For example ...

jene corua doiki pofe jwə london də => "Jane intends to walk through the forest to London" (from here)

jene cori doiki pofe jwə london də => "Jane walked through the forest to London" (from here)

However in other situations*, the actual sequence of individual events might be deemed less relevant, and there might be a tendancy to place the most important/surprising** event to the left. (No example)

kulua is leftmost, if present.

*For a verb chain that was ongoing. There would be a tendency for the first verb of unrealised part of the verb chain to take be in its base form with an n affix (perhaps preceded by gò). For example ...

jene core doiki gò pofe jwèn london də => "Jane has left on foot, she was intending to go through the forest and then on to London" ... [ there are actually two verb chains in this sentence ]

**This basically means that the elements most commonly used in verb chains appear towards the right (such as jò and té) and less common elements are towards the left ... types of locomotion would qualify here (actually doika is quite a common element, but maybe because it is deemed to be the same class as pyà, liwai, etc., it tends to be expressed quite early)

..

..

All the "Directional" verbs, "Types of locomotion" verbs and the "Haste" verb are intransitive.

All the "Relative motion" verbs are transitive (it sometimes looks like cùa "depart" and nyáu "return" are intransitive, they are actually transitive but the object ... has been dropped as it is obvious ... often "here").

..

The subject takes its ergative form or its naked form, depending on whether the first verb of the chain is transitive or intransitive. For example ...

ós byor (gò) kuluan nambo tə = He must hurry home .............................. ós as byó is transitive

ò kulor nambo tə = He hurries home ........................................................ ò as kulua is intransitive

ós london corua nambo tə = He will leave London and come home ......... ós as cùa is transitive

..

Now, just as in a non verb chain clause (i.e. if a noun appears to the left of the verb it is definite, if it appears to the right of the verb, it is indefinite), if a motion reference object is to the left of a relative motions verb it is definite, if it is to the right of a relative motions verb it is indefinite. This is demonstrated below ...

..

| nambo féu tə | to come out of the house | féu nambo tə | to come out of a house |

| nambo pòi jə | to go into the house | pòi nambo jə | to go into a house |

| nambo féu jə | to go out of the house | féu nambo jə | to go out of a house |

| nambo pòi tə | to come into the house | pòi nambo tə | to come into a house |

..

..

The directionals

..

Often jə or tə / bə or kə are tagged on at the end of a motion clause. Like a sort of afterthought. They give the utterance a bit more clarity ... a bit more resolution. For example ...

..

.............................. jaŋkori tə = "he ran towards us"

.............................. jaŋkori tə = "he ran towards us"

Note ... in the script the schwa is simply left out, so if you see a consonant standing by itself, you know that you have part of a verb chain.

If two directionals were to be used, jə or tə would follow bə or kə.

Obviously these 4 verbs often occur independently. In which case they are in their r-form.

this section is nothing to do with verb chains, just a bit to do with the usage of té and jò----

té is always intransitive. jò can be transitive or intransitive. For example ...

I am going to London => (pás) jar london ... however if the destination is not immediately after the verb í london (pás) jar

"I am going" or "I will go" => (pà) jaru

By the way ... if you go to meet somebody, jò and twá form a verb chain. For example ...

jò twə jono => to go and meet John

ojo twə jene => go and meet Jane (notice the irregular imperative)

..

..

* In contradistinction, when a origin comes immediately after the verb dwé "to come" the pilana -fi is never dropped.

..

..

HERE---------->---------LONDON

jó london = to go to London

jonos jor london = John is going to London

jonos jori cə london = John arrived in London (having travelled from here) ???

jono jori gò cùan london

HERE----------<---------LONDON

tè londonfi = to come from London

jono tor londonfi = John comes from London ....... ( in this case, it could be 20 years since John was last in London )

jono tori cə london = John comes from London ... ( in this case, John hs just arrived from London ) ..

.. When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the auxiliary verb. They are used where "up" and "down" are used in English.

bía = to ascend

kàu = to descend

CLIMB ʔupai kə = to climb down a tree

ʔupai CLIMB kə = to climb down the tree

CLIMB ʔupai bə = to climb up a tree

THROW toili kə = to throw down a book ???

These are also often inserted in verb chains to give extra information. The usually precede "come" and "go" when "come" and "go" are auxiliary verbs in the chain.

jò kə pə nambo = to go down into the house

jaŋkor kə pə nambo jə = he runs down into the house (away from us)

jaŋkor pə nambo kə tə = he runs down into the house (towards us)

The two above sentences could describe the exact same event. However there is some slight connotation in the latter that the descending happened at the same time as the entering (i.e. the entrance of the house was sloping ... somewhat unusual)

.. ..

..

He is lowering John down the cliff-face to the ledge => ós gora jono cliff gìa ledgeye ??

I dragged the dog along the road ??

joske pòi nambo = let's not let him go into the house ... there are 2 verbs in this chain ... jòi and pòi

jaŋkora bwá nambo dwía = he is running out the house (towards us) ... there are 3 verbs in this chain ... jaŋka, bwá and dwé

doikaya gàu pòi nambo jìa = Walk (command) down into the house (we are in the house) ... there are 4 verbs in this chain ... doika, gàu, pòi and jòi

Extensive use is made of serial verb constructions (SVC's). You can spot a SVC when you have a verb immediately followed (i.e. no pause and no particle) by another verb. Usually a SVC has two verbs but occasionally you will come across one with three verbs.

*Well maybe not always. For example jompa gàu means "rub down" or "erode". Now this can be a transitive verb or an intransitive verb. For example ...

1) The river erodes the stone

2) The stone erodes

With the transitive situation, the "river" is in no way going down, it is the stone. Cases where one of the verbs in a verb chain can have a different subject are limited to verbs such as erode (at least I think that now ??). Also the verbal noun for jompa gàu is not formed in the usual way for word building. Erosion = gaujompa

gaujompa or gajompa a verb in its own right ... I suppose that this would happen given time ??

I work as a translator ??? ... I work sàu translator ??

"want" ... "intend" ... etc. etc. are never part of verb chains ??

..

............... across & along & through

..

When in verb chains, these 3 verbs tend to be the main verb.

kwèu = to cross, to go/come over

plèu = to follow, to go/come along

cwá = to go/come through

komwe kwèu = to cross the road

komwe kwèu doika = to walk across the road

kwèu komwe doiki = to walk across a road

kwèu komwe doiki tə = to walk across a road (towards the speaker)

plèw and cwá follow the same pattern

Note ... some postpositions

komwe kwai = across the road = across a road

pintu cwai = through the door = along a road

Above are 2 postpositions ... derived from the participles kwewai and cwawai

komwe plewai = along the road

..

..

.............. here and there

..

awata = to wonder

jaŋka awata = to run around

..

............. bring and take

..

kli.o = a knife

kli.o ʔáu jə = to take the knife away

kli.o ʔáu tə = to bring the knife

ʔáu kli.o jə = to take a knife away

kli.o uʔau jə nə jono = take the knife and go give to John

kli.o uʔau tə nə jono = bring the knife and give to John

If however the knife was already in the 2nd person's hand, you would say ...

ute nə jono kli.o = come and give john the knife ... or ...

ute nə kli.o jonon = come and give the knife to john

Note ... the rules governing the 3 participants in a "giving", are exactly the same as English. Even to the fact that if you drop the participant you must include jowe which means away. For example ...

nari klogau tí jowe = I gave my shoes away.

Note ... In arithmetic ʔaujoi mean "to subtract" or "subtraction" : ledo means "to add" or "addition".

Note ... when somebody gives something "to themselves", tiye = must always be used, no matter its position.

..

The motion termini

..

día = arrive / reach

cùa leave / depart

The question about these is "how do they differ from -n and -fi ?"

The answer is that -n and -fi can sometimes mean "towards" and "away from".

día and cùa always mean "until" / "up to" / "all the way to" and "all the way from"

Also note that -n and -fi have a slightly more abstract usage ... for example -n indicated the dative for náu (to give) or bwinau (to show) etc. etc.

..

... Other Verb Chains

....... for and against

..

HELP = to help, assist, support

gompa = to hinder, to be against, to oppose

FIGHT = to fight

FIGHT jonotu = to fight with john ......... john is present and fighting

FIGHT HELP jono = to fight for John ... john is present but maybe not fighting

FIGHT jonoji = to fight for John ...........probably john not fighting and not present

FIGHT gompa jono = to fight against John

..

.......... to change

..

lái = to change

kwèu = to turn

lái sàu = to change into, to become

kwèu sàu = to turn into

The above 2 mean exactly the same

Note ...

paintori pintu nelau = he has painted a blue door

paintori pintu ʃìa nelau = he has painted a door blue

..

??? How does this mesh in with clauses starting with "want", "intend", "plan" etc. etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK BY DIXON ??

??? How does this mesh in with the concepts ...

"start", "stop", "to bodge", "to no affect", "scatter", "hurry", "to do accidentally" etc.etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK ON DYIRBAL BY DIXON

..

... IA and UA

..

| ìa | to finish, to complete |

| úa | to run out, to be exhausted, to be used up |

..

The first one being a transitive verb and the second one an intransitive verb.

Two fundamental concepts ... needed ever since humans started doing complex tasks and since humans started storing stuff for later use.

These two, as well as appearing in their "r-form" also appear as sentence final particles which could be analized as the final verb of a verb chains. Their forms are slightly irregular, but yə could be imagined as the i-form that ìa would take and wə could be imagined as the i-form that úa would take. These particles always appear to the extreme right of a sentence (but left of the @ particle). In the script, they are represented as simply y and w.

I finished building the house => (pás) nambo bundari yə

She finished off the cake => CAKE humpori wə

Notice that in the first example the object is fully formed (fully appeared) hence yə. In the second example the object has fully disappeared hence wə.

In some situations, either yə or wə would be appropriate.

For example "I finished reading the book" ... here the "pages to be read" have disappeared, but the "read pages" are at a maximum.

..

..

There does not seem to be any diachronic connection with the two affixes (ia and ua) which turn nouns into adjectives.

kloga = shoe : klogia = shod : klogua = unshod, shoeless

So it seems that any hint of semantic familiarity is just due to co-incidence.

..

yə and wə would be the i-form of the verbs yái "to have" and wòi "to think" (check this one out ???) but as these never participate in verb chains, there is no confusion.

..

..

Actually ... what would actually constitite the O argument of ìa is worth discussing.

There is always some underlying verb being referenced by ìa even though it is not expressed.

nambo ia.iri @ = have you finished the house ? ... here the underlying verb is bunda "to build"

And as another example ...

CAKE ia.iri @ = have you finished the cake ? ... actually here we have two possible underlying verbs : gàu "to make" or humpa "to eat" ... the one which is appropriate would be known from the background knowledge of the situation.

You could analyse ìa as

1) Always having a complement clause as O argument (with the maŋɡa usually dropped because it is so predictable.

2) Sometimes having a noun as O argument, and sometimes having a complement clause as O argument.

If analysis (1) is accepted, then ìa is the only verb that doesn't ... sometimes ... take a noun as its O argument.

Using R.M.W. Dixon's terminology ... ìa would be the only SECONDARY VERB* in the language of béu.

Actually in this case I think there is no benefit in analyzing ìa as (1) or (2). I know this leaves things a bit messy ... i.e. "pehaps there is only one SECONDARY VERB in béu. But one of the characteristics of natlangs is that they ARE messy. Think of ìa as my tribute to the messiness of natural languages :-)

[ As there is no benefit in analyzing an electron as either a particle alone or a wave alone. I find it a bit baffling to hear linguists arguing at length over ... say ... what is the "head" of a prepositional phrase is. "head" is just a construct to make it easy for linguists to talk about languages ... unfortunately it is part of the human psyche to believe that if you have a name for something, then that something must exist ... but I am digressing a bit here. ]