Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

..... The infinitive verb

..

A verb in its infinitive form (its most basic form) is called maŋga

About 32% of multi syllable maŋga end in "a".

About 16% of multi syllable maŋga end in "e", and the same for "o".

About 9% of multi syllable maŋga end in "au", and the same for "oi", "eu" and "ai".

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk .... not to walk

Where the RHS NP is the O argument and the LHS NP is the A argument.

A maŋga can be an argument in a clause ... just as a seŋko can. For example ...

The kitten playing with the string and the monkey eating the cake was very amusing. ???

(a noun would have the determiner "this", maŋga has the determiner "thus" wedi(if you demonstrate the action)or wede (if someone else demonstrates the action))

???

..

..... The indicative verb and affixes

..

To make a verb in the indicative mood, you must first deleted the final vowel from the infinitive. Then add affixes that indicate "agent", "indicative", "tense/aspect" and evidentiality. We will refer to these as slots 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. Only the first three slots are mandatory.

..

... Slot 1

..

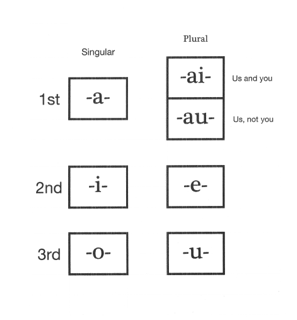

Slot 1 is for the agent ..

One of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer..

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikair and doikaur = we walk

doikir = you walk

doiker = you walk

doikor = he/she/it walks

doikur = they walk

..

... Slot 2

..

Slot 2 is for the indicative marker.

..

At this point we must introduce a new sound and a new letter.

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in grammatical suffixes and it indicates the indicative mood.

If you hear an "r", you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

..

... Slot 3

..

Slot 3 is for tense and aspect markers

..

There are 7 tense/aspect markers in béu

1) doikara = I am walking

This is the present tense

2) doikaro = I walk

This is the aortist tense. It actually encompasses past, present and future. Used for generic statements, such as ... "birds fly".

Actually the final o is always dropped unless there is an n or an s in the evidentiality slot.

So doikaro => doikar = I walk

3) doikaru = I will walk

This is the future tense

4) doikari = I walked

This is the past tense

5) doikare = I have walked

This is the perfect aspect.

6) doikarai = I had walked

This is the past perfect.

7) doikarau = I will have walked

This is the future perfect.

..

The perfect tense, logically doesn't differ that much difference from the past tense,. but it is emphasizing a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have -en".

For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch, this emphasizes the absence of John as opposed to "he went for lunch". The latter is just an action that happened in the past, the former is a present state brought about by a past action.

For another example ... "she read the book on geometry"

This doesn't specify whether she read it all the way thru or whether she just read a bit of it. Whereas ...

"she has read the book on geometry", implies she read the book all the way thru, but more importantly the connotation is that at the present time she has knowledge of geometry.

..

... Slot 4

..

Slot 4 is for the evidential markers (well three out of four are evidential markers)

..

The final slot (slot 4) is for the evidential marker

There are three markers that cites on what evidence the speaker is saying what he is saying. However it is not mandatory to stipulate on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In fact most occurrences of the indicative verb do not have an evidence marker.

The markers are as follows ...

1) -n

For example ... doikorin = "I guess that he walked" ... That is the speaker worked it out from circumstances/clues observed.

2) -s

For example ... doikoris = "They say he walked" ....... That is the speaker was told by some third party(ies) or overheard some third party(ies) talking.

3) -a

For example ... doikria = "he walked, I saw him" ...... That is the speaker saw it with his own eyes.

Note that the above evidential only co-occurs with the past tense.

Now there is a forth possibility for this slot ... and it is not actually an evidintial. Furthermore it has the same form as 3).

4) -a

For example ... doikorua = "he intends to walk" ... the agent in this case, of course, must be a sentient being (i.e. human).

Note that the above only co-occurs with the future tense.

..

..... The subjunctive verb

..

The subjunctive verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "s".

The subjunctive is called the sudəpe

The main thing about the subjunctive is that it is not "asserted" ... it is not insisted upon ... there is a shadow of doubt as to whether the action will actually take place.

This is in contrast to the indicative mood. In the indicative mood things definitely happen.

There are three places where the subjunctive turns up.

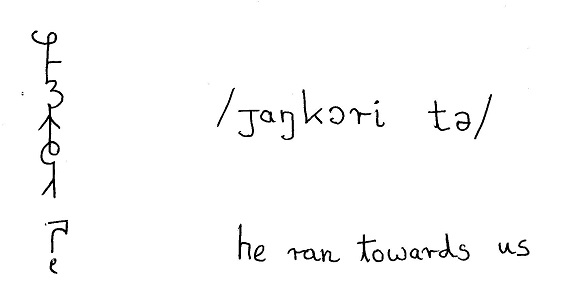

1) There are a set of leading verbs that always change there trailing verbs to the subjunctive. For example, the leading verbs "want", "wish", "prefer", "request/ask for", "suggest", "recommend", "love/like", "think/judge", "be afraid", "demand/command", "let/allow", "advise", "forbid" etc etc. Often with the above there is a particle tà immediately after the leading verb. However tà can be dropped sometimes.

2) After hà "if". For example hà doikos, doikas = If he walks, I will walk

Note the gap between the two parts of the sentence.

The above can be reconfigured a bit ... doikaru hà doikos = I will walk if he walks

Note that the first verb is in indicative form. Also no gap is needed (although you can put one in if you want)

"if only I could walk" ... the exact same construction is used in béu for wishful thinking.

3) As part of stand alone clauses ...

doikas = "should I walk" or "let me walk" or "how about me walking" or "can I walk" or "maybe I should walk"

There is never any need for the question particle ʔai? ... even though some of my translations are questions in English.

doikis = "maybe you should walk" or "why don't you walk" or "how about you walking"

doikos = "let him walk"

doikos jono = "let John walk"

For transitive verbs ...

timpos baus waulo = let the man hit the dog

? = God save the king

diablos ʔawos ò = May the Devil take him

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding bù (or should that be jù). For example ...

bù doikos = best not to let him walk

They locked him up so that he would starve to death

They let him out at night so that he would not starve to death

..

..... The imperative verb

..

This is used for giving orders. When you utter an imperative you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action (although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible).

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

1) First the final vowel of the infinitive is deleted and replaced with u.

doika = to walk

doiku = walk !

For monosyllabic verbs u is prefixed.

gàu = to do

ugau = do it !

The negative imperative is formed by putting the particle kyà before the infinitive.

kyà doika = Don't walk !

..

..... Examples of short verbs

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an indicative, subjunctive or imperative verb form is to delete the final vowel from the infinitive. However this is only applicable for multi-syllable words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different.

..

For a monosyllabic verbs the indicative endings and subjunctive suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive. For example ...

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ... swo.usk = lest they fear ...... etc.

..

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ... etc. etc.

..

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ... etc. etc.

..

..... Special short verbs

..

The above is the general rules for short verbs, however the 37 short verbs below the rules are different.

Their vowels of the infinitive are completely deleted for the indicative and subjunctive verb forms. For example ...

pòr nambo = he enters the house ... not *poi.or nambo

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to store | ||

| yái = to have | |||

| jò = to go | jwè = to undergo, to bear, to endure, to stand | ||

| féu = to exit | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

| bái = to rise | byó = to own | blèu = to hold | bwí = to see |

| gàu = to do | glù = to know | gwói = to pass | |

| día = to arrive, to reach | dwài = to pursue | ||

| lái = to change | |||

| cùa = to leave, to depart | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slòi = to stay | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kàu = to fall | kyò = to use | klói = to like | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyá = to fly | plèu = to follow | |

| té = to come | twá = to meet | ||

| wòi = to think | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to put |

The imperative prefix is -u for all* short verbs. For example ...

unyau nambo = go home !

uzwo = fear !

ugai = be in pain !

uʔau ʃì = take it !

.* All short verbs apart from one that is. jò "to go" has the imperative form ojo.

Some nouns related to the above ... yaivan = possessions, property, flovan = food, gauvan = products, myevan = reserves, nauvan = tax, tribute, gwàu = things that must be done, gwài = things that have been done, deeds, acts. gò = actions, behavior.

A particle related to the above ... yó ... a particle that indicates possession, occurs after the "possessed" and before the "possessor.

..

..... 4 slots before the verb

..

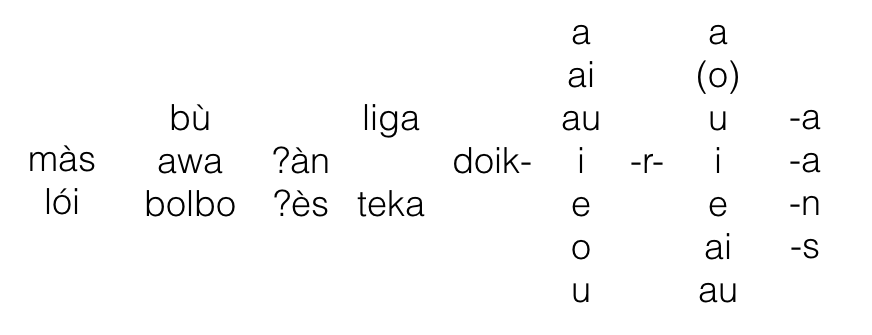

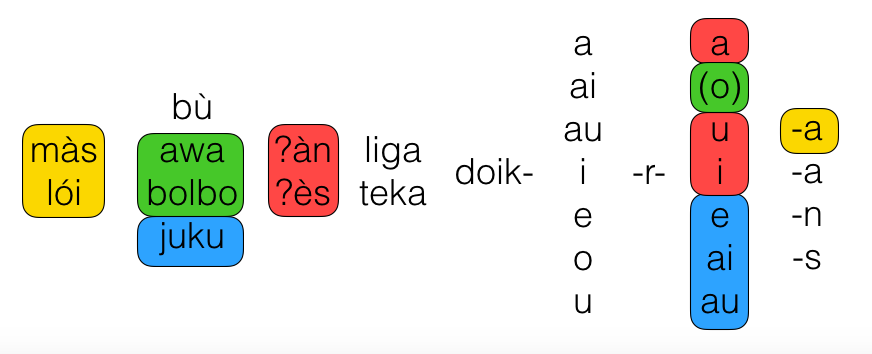

We have already covered the indicative with the 4 slots for "agent", "tense/aspect", " r " and "evidentiality" at the end of the denuded infinitive. As well as the nuances given by these post verbal slots, there are a set of nine particles which give further nuances to the basic indicative verb. These are called (near-standers ?). These particles occur in 4 pre-verbal slots. However these particles are independent word, not affixes.

These are shown (along with the 4 post-verbal slots) below ...

... Slot 1

..

These two particles indicate probability.

màs = possibly

lói = probably

Of course they cover a wide probability range but the average probability gleaned from hearing màs would probably be around 50 %, and for lói, maybe up near 90 %.

..

... Slot 2

..

bù is a negative particle which has scope over the entire sentence ... equivalent to "not" in English.

awa gives a "habitual but irregular" (maybe best translated as "now and again" or "occasionally" or even "not usually") meaning to the main verb. Possibly related to the verb awata ? which means "to wander".

bolbo gives a "habitual and regular" (best translated as "normally" or "usually" or "regularly") meaning to the main verb. Possibly related to the verb bolboi which means "to roll".

OK ... but if you are only allowed one of these five, how would you translate .. "I don't usually come to these parent-teacher meetings but ...."

Well you wont say ... awa tár to these parent-teacher nò twás _ ...."

..

... Slot 3

..

These are called aspectual operators or aspectual particles.

..

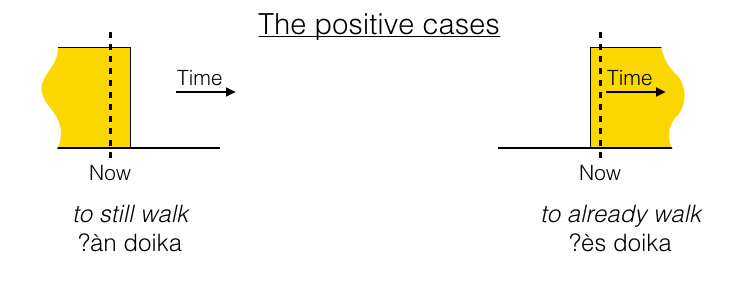

In English the nearest translations* are ʔàn = "still" and ʔès = "already".

Many many languages have equivalents to these two particles. For example ...

..

| English | still | already |

| German | noch | schon |

| béu | ʔàn | ʔès |

| French | encore | déjà |

| Mandarin | hái | yîjing |

| Dutch | nog | al |

| Russian | eščë | uže |

| Serbo-Croatian | još | već |

| Finnish | vielä | jo |

| Swedish | än(nu) | redan |

| Indonesian | masih | sudah |

..

ʔàn indicates ...

1) an activity is ongoing

2) the activity must stop some time in the future, possibly quite soon.

3) there is a certain expectation* that the activity should have stopped by now.

Possibly related to the verb ʔanto which means "to continue".

ʔès indicates ...

1) an activity is ongoing

2) the activity was not ongoing some time in the past, possibly quite recently.

3) there is a certain expectation** that the activity should not have started yet.

Possibly related to the verb ʔesto which means "to start".

..

A very interesting thing about these two words is their negation. Either the particle plus verb can be negated (shown by one bar above the two word) or the verb by itself can be negated (shown by a bar above the verb).

If the verb is negated ... then, on the diagram ... the yellow place becomes white and the white space becomes yellow.

If the particle plus verb is negated ... then, on the diagram ... the dashed line representing now, is translated to the other side of the barrier that represents onset/cessation of activity.

..

..

As you see by above ... by changing whether the negator act on the verb plus the operator or whether the operator acts on the negator plus the verb, negative sentenced with ʔàn and ʔès give diametrically opposite meanings*** (the proper technical term is to call them "dual operators").

Note that there are 4 possible negative cases to choose from and a language only needs 2. I guess a language (to cover all negative cases) should have either "(a) and (c)" or "(b) and (d)" or "(a) and (b)" or "(c) and (d)".

For example, all Slavic languages prefer verb negation, hence they tend to have (c) and (d). In German, only (a) and (c) are allowed in positive declarations. Nahuatl has negation of the operator so uses (a) and (b). It can be said that English is an a/b language also. However in the negative English uses suppletive forms for the two operators ... "yet" for "already" and "anymore" for "still" ... hence "not yet" and "not anymore".

In béu, bù negates the whole sentence**** (or maybe I should say ... the whole clause). So béu is an a/b language as well.

..

* However the English pattern is a bit irregular in that it has the particle "yet" which corresponds to ʔàn in some circumstances and to ʔès in other circumstances.

** I believe that this expectation is a connotation that will inevitable develop if you have prolonged usage of a particle with meaning 1 and 2.

*** I find this stuff very interesting. If you want to know more, read "The Meaning of Focus Particles" by Ekkehard König.

**** In béu the particle jù negates one element in a sentence (the element immediately following it). So instead of using (a) and (b) we might have had (c) and (d) in the form ... *?àn jù doika and *?ès jù doika.

..... A speaker of béu ... while recognizing the logic of *?àn jù doika and *?ès jù doika, would deem them ungrammatical.

..

... Slot 4

..

liga makes verbs which in themselves are quite compact timewise, more spread out. For example ...

..

| koʕia | to cough | liga koʕia | "to be coughing", "to have a coughing fit" |

| timpa | to hit | liga timpa | "to be hitting" or "to assault" |

..

liga is never used with verbs that typically have an inherent long time duration. For example ...

- liga glarua beuba kewe would be translated as "I intend to be knowing the language of béu well" ... Not really good English either.

lglarua beuba kewe = "I intend to know the language of béu well" ... is more felicitous in both languages.

..

liga gives an imperative slant to the main verb. Possibly related to the verb ligai which means "to stay" or "to lie". Now in the very best register of béu this particle is used for a certain poetic effect, it is used sparingly and is not necessary for understanding what is being said. However people that are L1 speakers of a language having a perfective/imperfective tend to over-use liga. This is not really a problem, it just shows that they are not L1 béu speakers. Conversely people that are L1 speakers of language that lacks this distinction tend to not use liga enough. Again ... no real problem.

..

teka is the opposite of liga. It means "momentarily". Possibly related to the verb telka which means "to slip a little bit". While in theory it can be used with almost any verb, it tends to be used disproportionately with a dozen or so verbs. For example ...

..

| bwí | to see | teka bwí | to catch a glimpse |

| wòi | to think | teka wòi | to think for a moment |

| ʕái | to want | teka ʕái | for a moment, to want |

..

... Restrictions

..

..

Certain members of slots 1,2 and 3 can only co-occur with a subset of the affixes in post-verbal slots 3 and 4.

YELLOW ... if you have màs or lói then in post-verbal slot 4 you can only have the -a that follows the future tense u (that is, the one that isn't really an evidential). However all affixes in slot 4 are not compulsary.

GREEN ... if you have awa or bolbo then in post-verbal slot 3 you can only have the aortist tense (the one that is the null affix).

RED ... if you have ʔàn or ʔès then in post-verbal slot 3 you can only have the present, future and past tenses.

BLUE ... we introduce another particle here ... juku meaning "never". It is a more emphatic negative than bù, but can only be used with the 3 perfect aspects in slot 3.

..

Most of the above restrictions don't need much comment. Hoewver in English there appears to be some conflation between "already" and the perfect aspect. For example "I've done it already". Maybe the reduced phonological prominence of the aspectual marker (i.e. "v") is a major contributing factor of this conflation. In béu ʔès and the three perfect aspectual markers are two different things.

1) When you use ʔès (or ʔàn) you are concerned about the onset/cessation of an event ... probably in the recent past or near future.

2) When you use the perfect aspect you are concerned about the state of the subject (A or S) which has resulted from some event that might be quite far in the past ... impinging on this is a stong "experential" connotation. For example ... if John has read a book on geometry, you can assume he has some knowledge of this subject. If he has been to London, you can assume he has many sounds and sights of London stored away in his memory.

..

Not to be confused with lò = "other" and kyulo = "again" These two particles come just in front of the verb. They are only used with the indicative verb and the maŋga.

..

..... Tying two clauses together

..

In béu we have live clauses and dead clause.

The head of a live clause is a verb in its declarative form.

The head of a dead clause is a verb in its declarative form.

A live clause has its main elements in any order, the S term is marked as the ergative. The A and O terms are unmarked.

A dead clause has word order VS or VAO, the O term being marked as the dative. The A and S terms are unmarked.

tàin = before

jáus = after

ʔéu = while, as

kyun = until

kyuvi = ever since

If the subjects (that is S or A) of two clauses are different then they can be conjoined timewise by using one of the above stand-alone particles. For example ...

1) jenes bwori jono ʔéu jonos fori nambo tí = Jane saw John as he was leaving his house.

Also ... as in English we can have the two clauses in the other order ...

2) ʔéu jonos fori nambo tí_jenes bwori ò = As John was leaving his house, Jane saw him

Notice that in this sentence, the second jono has been replaced by the pronoun ò ... in actual fact ... in 1) the chances are that jonos would be replaced by ós ... but this makes the sentence ambiguous.

John whistled as he left his house = jono wizori ʔéu ò fori nambo tí = *jono wizori ʔéu féu í nambo tí***

Rule (A) ... Now if the subjects of two clauses are the same, one of the clauses becomes a dead clause. A dead clause can not stand by itself but is dependent.

Rule (B) ... The clause with S becomes the dead clause. and

1) S while S ................... jono wizori huzuaʔeu = John whistled while smoking ... (must drop S, the linker must be appended to the infinitive)

2) A O while A O ..... jonos timpori jene ʔéu ós huzori ʃiga ... (pronoun used in second clause)

=> jonos timpori jene huzuaʔeu ʃigan ... (must drop A, the linker must be appended to the infinitive. O must be a single word)

3) A O while S .......... jonos timpori jene ʔéu ò huzori ... (pronoun used in second clause)

=> jonos timpori jene huzuaʔeu ... (must drop S, the linker must be appended to the infinitive)

4) S while A O ........... jono huzori ʔéu ós timpori jene .... (pronoun used in second clause)

=> jono huzori timpaʔeu jenen .... (must drop A, the linker must be appended to the infinitive. O must be a single word)

John left his house whistling = Jonos fori nambo tí ʔéu wiʒia

wiʒia = to whistle

koʔia = to cough

huzua = to smoke

..

..... Verb chains

..

béu has a technique that integrates two clauses even further. I call it the "verb chain". Let me demonstrate. Let's first translate ... "Yesterday John caught three fish."

yesterday = jana

to catch = holda

three = léu

a fish = fizai

So ... "Yesterday John caught three fish" => jana jonos holdri léu fizai

OK simple enough. Now how about "Yesterday John caught three fish, and then cooked and ate them"

In béu it is considered unnecessary to include person-tense information for "to cook" and "to eat". Well it is the same agents through-out and the tense is quite easy to deduce from the logic of the situation. So slanje (to cook) takes a special form that is only used in verb chains. The final vowel is changed to i. All multi syllable verbs take this transformation. Also all single syllable verbs change there final vowel to a schwa and loose their tone. Hence flò (to eat) becomes flə. So ...

..

1) "Yesterday John caught three fish, and then cooked and ate them" => jana jonos holdri léu fizai _ slanji _ flə

The above is an example of a verb chain.

The above three actions are deemed to be separated by some time period (however short), hence there are two short pauses (which I show by using an underline)

Let us look at another example. OK how about "All afternoon I was writing reports and answering the telephone"

afternoon = falaja

to write = kludau

report(noun) = fyakas

telephone(noun) = sweno

to answer = nyauze

..

2) "All afternoon I was writing reports and answering the telephone" => falaja ú kludar fyakas sweno nyauʒi

Unlike example 1), here the actions are interspersed randomly throughout the afternoon. There is considered no time between the actions, indeed they could possibly overlap, hence no pauses in 2)

It would also be possible to render the above as falaja ú sweno nyauzar kludi fyakas ... means the same thing.

Notice that in 2) we have two verb-object-pairs, (kludau, fyakas) and (sweno, nyauze). While an object must stay next to its verb, there is a tendency for it to precede the verb when it is definite and to follow it when indefinite).

Let us do another example. Let us translate "John walked along the road whistling"

to whistle = wiʒia

to walk = doika

to follow = plèu

road = komwe

..

3) John walked along the road whistling => jono doikri komwe plə wiʒi*

Unlike examples 1)and 2), here all the actions are considered simultaneous.

We can also express 3) as jonos komwe plri doiki wiʒi. In fact there are six ways in which the three verbs can be arranged. The meaning of the sentence would be exactly the same in all six cases.

Note that "John" appears "naked" or in his "s-marked" form depending on whether the first verb is V1 or V2. The first verb has the full verb train however later verbs in the chain have their reduced form.

*Actually this sentence is more likely to be expressed as jono doikri komwewo wiʒi

Let us do one last example ...

..

4)"The women were catching, cooking and eating fish all afternoon" => falaja ú galas holdur fizaia slanji flə

Because there are no pauses we would consider that the three processes were simultaneous (or at least that the "catching" overlapped with the "cooking" and the "cooking" overlapped with the "eating".

So it can be seen that the verb chain can give some idea as to its internal time structure. However it can not always give an accurate time structure in every situation and sometimes you must fall back to conjoining clauses with conjunctions.

[Note ... Although the verb chain is the common way to express when two actions happen at the same time, another method is possible. That is to make one of the verbs into an adjective. And then by placing this directly behind another verb you get an adverb. For example ... wizari doikala = I whistled while I walked]

..

..... The copula

..

The three components of a copular clause have a strict order. The same order as English in fact. Also the copula subject is always unmarked.

The copula is sàu.

However the indicative mood is not derived from the infinitive in the usual method.

.*sàr = I am

.*sàir = we are

.*sàur = we are

.*ʃìr = you are

.*sèr = you are

sòr = he/she/it is

sùr = they are

The indicative mood is invariably* shortened to simply r and appended directly to the copula subject. For example ...

jono r jini tè tomo r tumu = "John is clever but Thomas is stupid"

Note that r loses its tone as it is phonologically part of the last word of the subject NP ... it is an enclitic.

This "r" can build up tense/aspect and evidecial affixes as a normal verb. For example ...

jene gáu rìs hauʔe = "They say old Jane used to be beautiful"

Note that in this case the copula does not loose its tone. It is an independent word.

Also note that for copular clauses, the subject pronoun can never be dropped, because the pronoun information is gone (that is there is no component to the left of the "r").

wài r wikai tè nù r yubau = "we are weak but they are strong"

ʃì r broken = "it is broken"

*Well not invariably. If a copular subject doesn't end in a vowel and the copula has the aortist tense (i.e. no vowel), then we get the forms or and ur. or for a singular copular subject and ur for a plural copular subject. Again ... these forms are phonologically enclitics and have no tone.

..

Often the O argument of a V2 is dropped if it is considered too trivial be to worth bothering about. For example solbe (to drink) is a transitive verb but often the O argument can be unceremoniously dropped. The copula subject in certain situations is also dropped. These situations largely correspond to when English used the dummy subject "it". The reason for dropping the copula subject is almost the mirror image with respect to the dropping of the O argument. Whereas the O argument is thought too "trivial" or "predictable" the dropped copula subject is thought "all encompassing" or "so obvious that no need to mention it".

In these situations ... sòr (or occasionally sùr) is used.

Often used for talking about the weather (as in English).

This construction is used in particular with the words neʒi, boʒi, fain and aufain.

neʒi ... an adjective or noun = "necessary", "necessity", "that which is needed"

boʒi ... an adjective or noun = "better", "superior", "the best"(course of action)

fàin ... an adjective or noun = "fitting", "appropriate", "a good"(course of action)

and of course ufain is the opposite of fain. So ... for example ...

sòr neʒi tà .... = "you need to ..."

sòr boʒi tà .... = "best if you ..."

sòr fàin tà .... = "you had better ..."

[the copula would be sùr if two course of action were being proposed]

Now these three have a pretty fine degree of distinction between their meanings.

Of course people will not always pick the absolute correct word for every occasion. But there are nuances of meaning between the 3 words ...

fàin should be used when the advantage that the proposed course of action brings, is for the benefit of a third party and/or the proposed course of action will be approved of by society at large.

boʒi should be used when the benefits of the proposed course of action is mainly to the speaker or the speakee.

neʒi ... when followed by a clause in the past or perfect tense, means that from things apparent now, the course of action contained in the clause, must have happened in the past [i.e. so it is not a hundred miles away from the n evidential in the verb train]. When followed by a clause in the aortist or future tense ... then the meaning is not a hundred miles away from the modal sentences introduced by yái or byó.

And we have one other word that is commonly used with the above construction. That is maible. For example ...

sòr maible tà .... = "it's possible that ..."

sòr maible hè tà .... = "it's probable that ..."

Of course this usage is equivalent to using the particles màs and lói. The copula construction would be used when the main point of the utterance is to indicate the probability. màs and lói are used when the probability information is just an optional extra that was thrown in.

In careful speach the copula is retained in the above constructions. However in rapid informal speech, you will hear the copula dropped also.

..

There is another verb that also looses its subject for the same reason. yái is a normal V2 in every respect [i.e. its A argument takes the s-marker, it can be put in the passive form] apart from the fact that when its subject is missing it acts as an existential verb. For example ...

yór dèus = "there is a God", "God exists"

This is negated by negating the noun rather than negating the verb. For example ...

yór jù dèus = "there is no God", "God doesn't exists" .... not .. *yorj dèus

This existential construction often has a location incorporated into it. For example ...

yór yiŋki hè swedenʔi = "there are many attractive girls in Sweden" ... [the word here order is fixed].

The above means pretty much the same is the copula sentence ...

yiŋki hè r swedenʔi ... [and remember, all copula sentences are fixed word order].

Which in turn means pretty much the same as the normal transitive clause ...

swedenes yór yiŋki hè ... [free word order]

..

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences