Béu : Chapter 10

..... Overview of language structure

..

The following section lays out the linguistics terminology which the béu linguists use to describe their language.

..

..

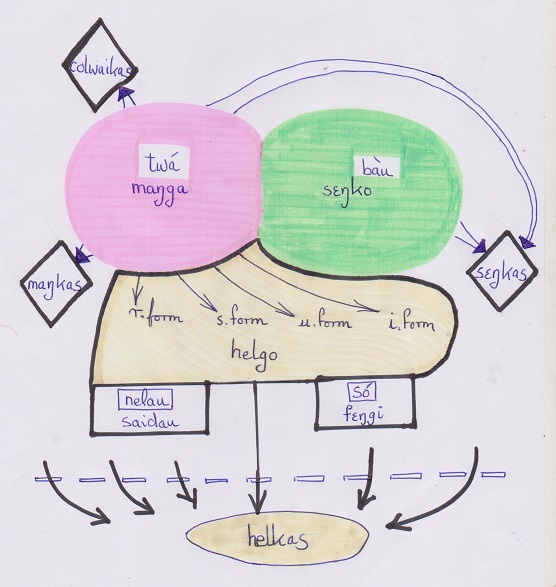

In nandəli .. "dictionary" all entries are assigned to four categories ...

1) seŋko = object, a material thing that can be seen and touched.

An example of a seŋko is bàu .. "a man"

..

2) maŋga ... I guess "infinitive verb" is the nearest translation we can get. Or maybe the Arabic term "masDar" would be better. Anyway I have been using the term maŋga from the beginning of this document as I have been too lazy to type out "infinitive verb" innumerable times.

An example of a maŋga is twá .. "to meet" or "meeting"

..

3) saidau = adjective

An example of a saidau is nelau .. "dark blue"

..

4) feŋgi = particle ... this is a sort of "hold-all" category for all words (and affixes) that don't neatly fit into the first three categories. I suppose that various "sub-categories" of the category feŋgi could be discussed. However I don't think that is profitable at this juncture.

An example of a feŋgi is só .. the preposition that shows a noun is ergative case.

..

Another important word category is helgo .. "finite verb". That is .. a verb in its r.form, s.form, u.form or i.form.

So helgo are derived from manga. [related words ... helga = "to live" and helgi = "alive"]

..

A seŋko can be expanded by the addition of other elements to a seŋkas "a noun phrase". Actually it means "noun OR noun phrase", so the entries in a dictionary might be designated seŋko but in most discussions about grammar one comes across, simply seŋkas.

An example of a seŋkas is bàu nelau dè .. "that blue man"

A maŋga can also be expanded into a seŋkas. For example ... twá mutu dè .. "that important meeting".

Furthermore a maŋga can also be expanded into what is called a maŋkas*. Maybe best translated as "gerund phrase". The structure of a maŋkas can be derived from the structure of helkas ... Oh wait a minute, we haven't said what a helkas is yet ...

Just as a maŋga can be expanded into a maŋkas, by adding elements ... and the seŋko into a seŋkas ... a helgo can be expanded into a helkas .. "a clause".

OK ... now that we know what a helkas is we can go back to the maŋkas. Mmmhhh ... maybe the best way to explain it is just to do an example ...

falaja jonos jene timpuri pobomau "John hit Jane in the afternoon on top of the mountain" .... this is a helkas

The corresponding maŋkas would be jono timpa jene pobomau falaja ... "John's hitting Jane in the afternoon on top of the mountain"

The above maŋkas could appear in a clause as S, O or A argument.

..

There is something also called a colwaikas ... a bit of an amalgam of a seŋkas and a maŋkas. But this is quite a marginal construction. We won't worry about it at the moment.

.* Actually it means "gerund OR gerund phrase", so while the entries in a dictionary are designated maŋga, in most grammatical writing, you just comes across the term .. maŋkas.

..

..... More details about maŋkas and colwaikas

..

As we know, the main elements in a helkas are free. That is the S, A and O arguments can appear either side of the verb.However in other areas word order is not so free. For example in copula clauses. Also maŋkas does not have free word order. So how exactly is it done ... how do we derive maŋkas which has fixed word order from seŋkas which has free word order. Well the element that is marked on the helkas by the vowel just before the "r", comes immediately to the left of the maŋga. Also note that even though this is often dropped in seŋkas it can not in maŋkas*. The O argument (naked noun) of the helkas must come immediately after the maŋga in the maŋkas. Any other peripheral arguments are stuck on at the end.

The helkas = solbari saco he? moze pona = I drank some cold water very quickly

Derived maŋkas = pà solbe moze pona sacowe ... which can be an argument in another helkas or copula clause ...

pà solbe moze pona sacowe r kéu = my drinking the cold water quickly was bad

..

.*Well actually it is dropped in certain circumstances. For example ...

ʔár solbe moze = I want to drink water

..

If you see a maŋga surrounded by other elements, how do you know if you have a maŋkas or a seŋkas. Well in the maŋkas the manga can not be plural or have any possessors for one thing.

..

..... Beyond the pilana

- This chapter should follow the pilana by about 2 chapters **

This chapter shows how to express things when a finer graduation is needed than can be expressed by the pilana. It also goes into how the pilana are used in greater detail.

Previously we have mentioned the first 8 pilana which are used for specifying location. Now there are two other words that are important for specifying location, namely tài and jáu (meaning , “in front of” and “behind”).

We must be careful here. In English usage “behind” can mean “at the far side of" as well as "at the backside". The same with “in front of” (but to a lesser extent). In béu, tài and jáu can only be used with objects that have a well defined “front” and “back”. Typically these objects are humans but tài and jáu can also be used with … for example “a house”. They can not be used with object which lack a front and a back. For instance they can not be used with "mountain".

Now no pilana can be a noun in its own right. They must always appear either suffixed on to a noun or standing in front of a NP. Now béu usually likes to drop the topic. But how can we drop the topic when we need no give a location with respect to a certain noun (which is the topic).

In English, we sometimes can have "above", "below, "in front", "behind" occurring alone. Consider ...

"They were in dire straits, in front the deep blue sea, behind the murderous viking raiders"

In the above sentence "in front" and "behind" can be considered nouns.*

pilana 1 - 8 plus tài and jáu only occur in front of a NP or suffixed to a noun.

However they can become nouns in their own right if they are suffixed to the particle dá (place). For example …

| pida | the interior |

| mauda | above, topside |

| goida | the underneath |

| taida | the front |

| jauda | the backside, the back |

| lada | the surface |

| ceda | this side |

| duada | the far side |

| beneda | the right |

| komoda | the left |

*An alternative analysis is to consider "They were in dire straits, in front the deep blue sea, behind the murderous viking raiders" as an abbreviation for "They were in dire straits, in front of them the deep blue sea, behind them the murderous viking raiders"

Earlier we told you that a pilana positional phrase can be considered either to be an adjective or a adverb. However using the above table we can produce nominal equivalents of them.

dapi nambo (sòr) detia = the interior of the house is elegant OR inside the house in elegant

(??? to think about further)The above can sometimes occur as ...

dapi nambowo (sòr) detia but this is unusual. It might possibly happen if the NP is complex. For example ...

dapi wò nambo jutu dè (sòr) detia (Note wò here is not defining a roll in a sentence, but a roll in a NP) .... NNNNNNNNNNNNN

Actually "They were in dire straits, in front the deep blue sea, behind the murderous viking raiders" can be translated into béu .... EITHER using datai and dajau OR nutai and nujau.

da is an interesting particle. It never occurs as a word it its own right. But as well as appearing as a component in the table above it appears as a suffix meaning "place" or "shop".

If béu had a history, you would speculate that it once was a noun with a meaning something like "place". But it hasn't.

Note ... the word for "here" dían and "there" dèn could also have a connection.

And compare dí "this" and dè "that" ... it is all very mysterious.

Note ... pilana 15 does not combine with da-. However there is a particle dan : it is equivalent to the English word "than". For example ...

jene (sòr) yubauge dan jono = Jane is stronger than John

Again ... all very mysterious.

Occasionally you get them joined to -ʔau. For example …

piʔau = interior surface

là can also be joined to -ʔau. For example …

laʔau = on it

Note ... piʔai wò nambo means exactly the same as nambopi. Invariably the terser form is used.

9) -ye ... yé ... The dative. Some usage example ...

He made the prisoner sing = He give sing prisonerye

I tell jane that ... i to jane tell that .... THIS IS SIMILAR TO "TO GIVE"

glá nòr flovan beggarsye = she gives food to the beggars

nauya toili oye = give a book to her

Note ... the béu way is similar to English. For example ... toili nauya ò = give the book to her

This is the pilana used for marking the receiver of a gift, or the receiver of some knowledge.

However the basic usage of the word is directional.

namboye = "to the house"

yé wazbo nambo = "as far as the house" ... (literally "to the distance of the house")

yé limit/border nambo = "up to the house" ... for objects

doikori yé face báu "he has walked up to the man" ... for people

10) -vi ... fì ... The ablative. Some usage example ...

mari laula guardfi = I was made to sing by the guard

I hear from Jane that .... Similar to English ... you can not miss out "from", even with Jane directly behind the verb

The beggars mor flovan glavi = the beggar get food from the woman

nambovi = "from the house"

fí "direction" nambo = "away from the house"

fí "limit/border" nambo = all the way from the house

fí nambomau = from the top of the house

Note ... two appended pilana are not allowed ... so *nambomauvi is not allowed

lori sàu yemevi yé prince handsome = he changed from a frog to a handsome prince

11) -tu ... tù ... The instrumental/comitative. Some usage example ...

kli.otu = John opened the can with a knife

jenetu = John went to town with Jane

Also used when something is achieved through a certain action ...

banu = to learn

banutu = by learning

Two particles are related to this pilana

tuta = because ... when because is followed by a clause

tuwo = because ... when "because" is followed by a NP.

Note ... duva = hand, arm .... duvatu = manually

Usuage ??? mountain cloud.ia = the cloudy mountain

mountain tù many rain clouds = the cloudy mountain ??? (Note tù here is not defining a roll in a sentence, but a roll in a NP) .... NNNNNNNNNNNNN

12) -ji ... jì ... The benefactive. Usually it refers to a person. However it often also occurs with an infinitive. Some usage example ...

banu = to learn

banuji = in order to learn

jari tweji ò = I have gone (in order) to meet him ... in this case it is not stated whether the "meeting" was successful or not

jari twé ò = I have gone and met him ... this is a verb chain

13) -wo ... wò ... The respective. Some usage example ...

pà halfar = I laugh LAUGH ???

pà halfar jonowo = I laugh at John

Can be used to show motion w.r.t. something .... "I lower the boy down the cliff face" ... here "down" = wò

Used for marking the "theme" as in such sentences as ...

gala catura jonowo = the women are talking about John

Also when fronted, it gives a topic of a topic/comment sentence. For example ...

jonowo ... = as for John ....

14) -n ... nà ... The locative

at

15) -s ... sá ... The ergative

só tá ........ = that Stefen turned up drunk at the interview sank his chance of getting the job

16) -lya ... alya ... The allative. Some usage example ...

xxx yyy zzz = put the cushions on the sofa

17) -lfe ... alfe ... The delative

xxx yyy zzz = the frog jumps off the lily pad

..

..... More on verb chains

..

............ He is lowering John down the cliff-face to the ledge => ós gora jono cliff gìa ledgeye ??

I dragged the dog along the road ??

joske pòi nambo = let's not let him go into the house ... there are 2 verbs in this chain ... jòi and pòi

jaŋkora bwá nambo dwía = he is running out the house (towards us) ... there are 3 verbs in this chain ... jaŋka, bwá and dwé

doikaya gàu pòi nambo jìa = Walk (command) down into the house (we are in the house) ... there are 4 verbs in this chain ... doika, gàu, pòi and jòi

Extensive use is made of serial verb constructions (SVC's). You can spot a SVC when you have a verb immediately followed (i.e. no pause and no particle) by another verb. Usually a SVC has two verbs but occasionally you will come across one with three verbs.

*Well maybe not always. For example jompa gàu means "rub down" or "erode". Now this can be a transitive verb or an intransitive verb. For example ...

1) The river erodes the stone

2) The stone erodes

With the transitive situation, the "river" is in no way going down, it is the stone. Cases where one of the verbs in a verb chain can have a different subject are limited to verbs such as erode (at least I think that now ??). Also the verbal noun for jompa gàu is not formed in the usual way for word building. Erosion = gaujompa

gaujompa or gajompa a verb in its own right ... I suppose that this would happen given time ??

I work as a translator ??? ... I work sàu translator ??

"want" ... "intend" ... etc. etc. are never part of verb chains ?? ..........................................

........... Unbalanced

..

Now all the above were examples of "one off" or "balanced" verb chains ( "balanced" in the sense that all the verbs have about the same likelihood ). A more common type of verb chain is one in which some common verb is appended to a clause to give some extra information. Examples of these verbs are ... "enter", "exit", "cross", "follow", "to go through", "come", "go", etc. etc. etc.

................. enter and exit

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the main verb. They are used where "into" and "out of" are used in English.

pòi = to enter

féu = to exit

nambo féu tə = to come out of the house

nambo pòi jə = to go into the house

nambo pòi tə = to come into the house

nambo féu jə = to go out of the house

féu nambo tə = to come out of a house

féu nambo jə = to go into a house

pòi nambo tə = to come into a house

féu nambo jə = to go out of a house

nambo féu jaŋki tə = to run out the house (towards us)

féu nambo jaŋki tə = to run out a house (towards us)

..

............... across & along & through

..

When in verb chains, these 3 verbs tend to be the main verb.

kwèu = to cross, to go/come over

plèu = to follow, to go/come along

cwá = to go/come through

komwe kwèu = to cross the road

komwe kwèu doika = to walk across the road

kwèu komwe doiki = to walk across a road

kwèu komwe doiki tə = to walk across a road (towards the speaker)

plèw and cwá follow the same pattern

Note ... some postpositions

komwe kwai = across the road = across a road

pintu cwai = through the door = along a road

Above are 2 postpositions ... derived from the participles kwewai and cwawai

komwe plewai = along the road

..

............ come and go

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the auxiliary verb.

Obviously they often occur as simple verbs.

"come", "go", "up" and "down" are often stuck on to the end of an utterance ... like a sort of afterthought. They give the utterance a bit more clarity ... a bit more resolution.

The below is nothing to do with verb chains, just a bit to do with the usage of dwé and jòi.

..

HERE------------>--------LONDON

londonye jòi = to go to London ... however if the destination immediately follows jòi -ye is dropped*. So ...

SIMILAR TO ADVERBS + GIVE ... LIGHT GREEN HI-LIGHT

jó london = to go to London

jó twì jono = to go to meet John (twe = to meet ??)

* In contradistinction, when a origin comes immediately after the verb dwé "to come" the pilana -fi is never dropped.

..

HERE----------<---------LONDON

tè londonfi = to come from London

tè jonovi = to come from John

..

.............. ascend and descend

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the auxiliary verb. They are used where "up" and "down" are used in English.

bía = to ascend

kàu = to descend

CLIMB ʔupai kə = to climb down a tree

ʔupai CLIMB kə = to climb down the tree

CLIMB ʔupai bə = to climb up a tree

THROW toili kə = to throw down a book ???

These are also often inserted in verb chains to give extra information. The usually precede "come" and "go" when "come" and "go" are auxiliary verbs in the chain.

jò kə pə nambo = to go down into the house

jaŋkor kə pə nambo jə = he runs down into the house (away from us)

jaŋkor pə nambo kə tə = he runs down into the house (towards us)

The two above sentences could describe the exact same event. However there is some slight connotation in the latter that the descending happened at the same time as the entering (i.e. the entrance of the house was sloping ... somewhat unusual)

..

.............. here and there

..

awata = to wonder

jaŋka awata = to run around

..

............. bring and take

..

kli.o = a knife

kli.o ʔáu jə = to take the knife away

kli.o ʔáu tə = to bring the knife

ʔáu kli.o jə = to take a knife away

kli.o uʔau jə nə jono = take the knife and go give to John

kli.o uʔau tə nə jono = bring the knife and give to John

If however the knife was already in the 2nd person's hand, you would say ...

ute nə jono kli.o = come and give john the knife ... or ...

ute nə kli.o jonon = come and give the knife to john

Note ... the rules governing the 3 participants in a "giving", are exactly the same as English. Even to the fact that if you drop the participant you must include jowe which means away. For example ...

nari klogau tí jowe = I gave my shoes away.

Note ... In arithmetic ʔaujoi mean "to subtract" or "subtraction" : ledo means "to add" or "addition".

Note ... when somebody gives something "to themselves", tiye = must always be used, no matter its position.

..

....... for and against

..

HELP = to help, assist, support

gompa = to hinder, to be against, to oppose

FIGHT = to fight

FIGHT jonotu = to fight with john ......... john is present and fighting

FIGHT HELP jono = to fight for John ... john is present but maybe not fighting

FIGHT jonoji = to fight for John ...........probably john not fighting and not present

FIGHT gompa jono = to fight against John

..

.......... to change

..

lái = to change

kwèu = to turn

lái sàu = to change into, to become

kwèu sàu = to turn into

The above 2 mean exactly the same

Note ...

paintori pintu nelau = he has painted a blue door

paintori pintu ʃìa nelau = he has painted a door blue

..

??? How does this mesh in with clauses starting with "want", "intend", "plan" etc. etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK BY DIXON ??

??? How does this mesh in with the concepts ...

"start", "stop", "to bodge", "to no affect", "scatter", "hurry", "to do accidentally" etc.etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK ON DYIRBAL BY DIXON

..

... Parenthesis

..

béu has two particles that indicate the start of some sort of parenthesis. In a similar way to a mathematical formula, where brackets mean that the arguments within the brackets should be evaluated first, the two béu particles indicate that the immediately following clause should be processed (by the brain) before arguments outside of the parenthesis are considered.

..

. tà ... the full clause particle

..

This is basically the same as "that" in English, when "that" introduces a complement clause. For example ...

"He said THAT he was not feeling well"

Notice that "he was not feeling well" is complete in itself, it is a self-contained clause.

..

. ʔà ... the gap clause particle

..

This is basically the same as "what" in English, in such sentences as ...

"WHAT you see is WHAT you get"*

Notice that "you see" and "you get" are not complete clauses, there is a "gap" in them.

The phase "WHAT you see", (to return to the mathematical analogy again) may be thought of as a "variable". in this case, the motivation for using a "variable", is to make the expression "general" rather than "specific". (Being general it is of course more worthy of our consideration). Other motivations for using a "variable" is that the actual argument is not known. Yet another is that even though the particular argument is known, it is really awkward to specify satisfactorily.

EXAMPLE

Another way to think about the ʔà construction, is to think of it as a "nominaliser", a particle that turns a whole clause into a noun. To use the example from just above ....

"see" is an intransitive verb with two arguments. To replace one of these arguments by ʔà is like defining the missing argument in terms of the rest of the clause i.e. it changes a clause into a constuction that refers to one argument of that clause.

. Gap clause particles in other languages

There is no generally agreed upon term for the type of construction which I am calling "gap clause" here. Dixon calls it a "fused relative", Greenberg calls it a "headless relative clause". I don't like either term. A fused relative implies that a generic noun (i.e. "thing" or "person") somehow got fused with a relativizer. This certainly never happened although this type of clause can be rewritten as a generic noun followed by a relativizer. As for "headless" relative clause ... well I think the type of clause that we are dealing with is in fact more fundamental then a relative clause, so I would not like to define it in terms of a relative clause.

My thoughts on this type of clause are ...

Well "what" was firstly a question word. So you have expressions like "Who fed the cat"

Then of course it is natural to have an answer like "I don't know who fed the cat"

Now the above sentence is similar to "I don't know French" or "I don't know Johnny".

Now you see the expression "who fed the cat" fills the slot usually occupied by a noun in an "I don't know" sentences.

So "who fed the cat" started to be thought of as a sort of noun.

Now from the "know (neg)" beachhead*, the usage would have spread to "know" and also the such words that have "knowing" as an essential part of their meaning. Words such as "remember", "report" etc. etc.

*I call "know (neg)" a "beachhead"**. A beachhead is a usage(and/or the act or situation behind that usage) that facilitates the meaning of a word to spread. Or the meaning of an expression to spread. A beachhead can be defined simply as an expression, but sometimes some background as to the speakers environment has to be given. For example suppose that one dialect of a language was using a word to mean "under", but this same word meant "between/among" in all other dialects. Now suppose you did some investigating and found that all other dialects of this language was spoken on the steppes and their speakers made a living by animal husbandry. However the group which diverged from the others had given up the nomadic life and settled down in a lush river valley. In this valley their main occupation was tending their fruit orchards.

It could be deduced that the change in meaning came about by people saying ... "Johnny is among the trees". Now as the trees were thick on the ground and had overspreading branches, this was reanalysed to mean "Johnny is under the trees". Hence I would say ...

The beachhead of word "x" = "between" to word "x" = "under" was the expression "among the trees" (and in this case a bit of background as to the "culture" of the speakers would be appropriate). ... OK ? ... understood ?

For an expressing to become a beachhead, it must, of course, be used regularly.

ASIDE ... I have thought about counting rosary beads as a possible beachhead that changed the meaning of "have", in Western Europe, from purely "possession" to a perfect marker. This is just (fairly ?) wild conjecture of course. (The beachhead expression being "I have x beads counted" with "counted" originally being a passive participle)

I am digressing here ... well to get back to "who fed the cat". We had it being considered a sort of noun. Presumably it was at one time put directly after a noun in apposition (presumably with a period of silence between the two) and qualified the noun. Then presumably they got bound closer together, the gap was lost, and this is the history of one form of relative clause in English.

**Actually I would have liked to use the term pivot here. However this term has already been taken.

From the dictionary

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 1. A position on an enemy shoreline captured by troops in advance of an invading force

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 2. A first achievement that opens the way for further developments.

There are 4 relativizers ... ʔá, ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja. (relativizer = ʔasemo-marker)

ʔasemo = relative clause.

It works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. The béu relativisers is ʔá. Though ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja also have roles as relativisers.

The main relativiser is ʔá and all the pilana can occur with it (well all the pilana except ʔe. ʔaí is used instead of * ʔaʔe).

The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its pilana on the suffixed to the relativizer. For example ;-

glà ʔá bwás timpori rà hauʔe = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful.

bwá ʔás timpori glà rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

The same thing happens with all the pilana. For example ;-

the basket ʔapi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ʔala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman ʔaye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town ʔafi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad ʔalya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

the boat ʔalfe you have just jumped is unsound

báu ʔás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

- nambo ʔaʔe she lives is the biggest in town.

báu ʔaho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife ʔatu he severed the branch is a 100 years old

báu ʔán dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police*

The old woman ʔaji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy ʔaco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

*Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. n marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause.

As you see in above, ʔa in the form * ʔaʔe is not allowed. Instead you must use ʔaí.

The use of ʔái and ʔàu as relativizers are basically the same as the use of "where" and "when" in English. These two can combine with two of the pilana.

?aifi = from where, whence

?aiye = to where, hence

?aufi = from when, since

?auye = to when, until

The use of ʔaja basically is a relativizer for an entire clause instead of just the noun which it follows.

For example ???????

WITH SPACE AND TIME

PLURAL FORM

..

... the NP with the present participle core ??

..

Now the phrase jono kludala toili is a noun phrase (NP) in which the adjective phrase (AP) qualifies the noun jono

(Notice that in the clause that corresponds to the above NP, jonos kludora toili (John is writing the book), jono has the ergative suffix and the 3 words can occur in any order : with the NP, jono does not take the ergative suffix and the 3 words must occur in the order shown.)

glói = to see

polo = Paul

timpa = to hit

jene = Jenny

glori polo timpala é = He saw paul hitting something

glori pà timpala ò = He saw me hitting her

glori hà (pás) timparwi ò = He saw that I had hit her

glori jene timpwala = He saw Jenny being hit

Now the question is where is this special NP used. Well it is used in situations where English would use a complement clause. For example with algo meaning "to think about",*

1) algara jono = I am thinking about John.

2) algara jono kludala toili = I am thinking about John writing a book.

Note ... According to Dixon, the standard English translation of 2) would be "I am thinking about John's writing a book" which I find quite strange even though English is my mother tongue. I have decided to call this sort of construction in béu a special kind of NP, while Dixon has called the equivalent expression in English the "-ing" type of complement clause. I think this is just a naming thing and doesn't really matter.

*"to think (that)" is alhu in béu. alhu also translates "to believe".

..

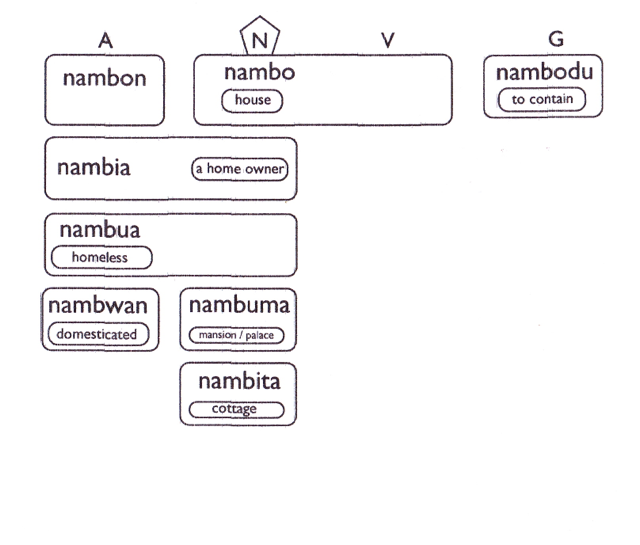

..... Nouns and how they pervade other parts of speech

nambo

nambo meaning house is a fairly typical non-single-syllable noun and we can use it to demonstrate how béu generates other words from nouns.

nambodu

Not many nouns can be used as verbs. However when an action is associated to a certain noun, usually, with no change of form, it can be used as a verb. For example lotova means bicycle and you get lotovarwi meaning "I used to ride my bicycle". For the infinitive, du must be affixed to the basic form.

The meaning given to the verb nambo is arrived at through metaphor, it is not so straight forward as the bicycle example.

The use of all tools can be expressed in a similar manner to lotova.

nambon

Sometimes in English a bare noun can be used to qualify another noun (i.e. it can act as an adjective). For example in the phrase "history teacher", "history" has the roll usually performed by an adjective ... for example, "the sadistic teacher". This can never happen in béu, the noun must undergo some sort of change. The most common change for nambo is it to change into its genitive form nambon as in pintu nambon "the door of the house". Other changes that can occur are the affixation of -go or -ka. These are used with certain nouns more than others. They are not used that much with the noun nambo so I haven't included them in the chart above. You could use the forms nambogo or namboka if you wanted tho' (they would mean "house-like"). Maybe you would use one of these terms in a joke ... it would stike the listener as slightly odd however.

nambia

This is a very common derivation. Nearly all nouns can take this transformation.

nambia is an adjective meaning "having a home". And its use as a noun is quite common as well, in which case it would probably be translater as "a home owner"

nambua

Also a very common derivation. The opposite of nambia.

nambua means homeless or the homeless

Note that although ia and ua are exact opposites, the usage of the words produced from these affixes do not completely mirror each other. It all depends oner what the base word is.

For example, in this case, the form nambia is a bit rarer than nambia. Also nambua is used more often as an adjective than as a noun, while nambia is used more often as a noun than an adjective.

nambuma

Many of the worlds languages have a suffix that has this roll. Called an "augmentative" in the Western linguistic tradition. Does not really come into play in English but quite common in béu. As well as some basic forms that appear regularly in their augmentative version, any noun can receive this affix. But of course it will stick out if it is not commonly used.

nambita

The opposite of nambuma. Called an "diminutive" in the Western linguistic tradition. In béu it is often used to show that the speaker feels affection for the noun so transformed. There is no trace of the opposite for the augmentative : nobody would use the augmentative to show repulsion.

nambwan

The form changes that produce nambia, nambua, nambuma, nambita, *nambija are *nambeba affected by deleting the final vowel (or diphthong) and then adding the relevant affix. However with this change of form this is not always possible to delete the final vowel (example). In this example it is possible. In fact it is possible if the final consonant of the base word is j, b, g, d,c, s, k, t, l or m.

By the way nambwan means domestic or domesticated. Nearly always when you come across the word it is referring to animals.

Other derivations that are not possible with nambo

I have already mentioned nambogo and namboka which while possible, are not at all common. Also I will mention three other derivations that are quite common however can not occur with nambo.

1) -ija is affixed to the names of animals and give a word meaning the young of that animal. For example;-

huvu = sheep

huvija = lamb

mèu = cat

meuja = kitten

2) -eba is an affix that produces a word meaning "a set of something" where the base word is considered as a central/typical member of that set. For example;-

baiʔo = spoon

baiʔeba = cutlery

= chair

= furniture

nambeba could represent a set comprising (houses, huts, skyscrapers, apartment buildings, government buildings etc etc.), however this is already covered by bundo (derived from the verb bunda "to build").

báu

..... -uʒi and -go

Note that wan tends to be affixed to nouns while uzhi gets affixed to verbs.

| to play | lento | playful | lentuʒi |

| to rest/relax | loŋge | lazy | loŋguʒi |

| to lie | selne | untruthful by disposition | selnuʒi |

| to work | kodai | diligent | koduʒi |

If the verb is monosyllabic, then -go is used instead of -uʒi.

Sometimes it is hard to tell if a word is basically a verb or a noun.

For example eskua is the gomia of a verb which means "to be angry". However it is also a noun meaning "anger".

However we can say that it is basically a verb as eskuʒi "bad tempered" !!!

How do we say "angry" ???

..... Number of categories

So now we can say, béu has ...

1 wepua

2 mazeba .......................... and 2 demonstratives

3 plova ......... participles ........ ʔinʔanandau or whatever words

4 teŋko ........ evidentials ........ relativizers or ʔasemo-marker

5 seŋgeba ..... modals ..... and 5 specifyana

6 ʔanandau ... question words

7 cenʔo ......... subject marked on the verb

9 ??? .............. personal pronouns

12 pilana (noun cases),

15 "specified"

16 gwoma (tense/aspect verbal affixes).

best to have 10 ??? conjunctions ???

The complement clause construction ???

wí = to see polo = Paul timpa = to hit jene = Jenny

wori polo timpa andai = He saw paul hitting something

wori pá timpana ó = He saw me hitting her

wori jene bwò timpa = He saw Jenny being hit

wori polo timpa jene = He saw Paul hitting Jenny

wori pà timpa jene = He saw me hitting Jenny.

In the above constructions the word order must be as shown above.

TO THINK ABOUT

Now we have said before that béu has free word order, however this really only applies to the verb in R-form (R) and the S argument in an intransitive clause, and the R, A and O in a transitive clause. When you have a verb in gomia-form (G), in the subjunctive form (Sub) or in the imperative form (Imp), you must have these elements in the following order ;-

S G : S Sub ... the last of these (S -S ) is quite unusual. Maybe can have S I ... but then S must be in vocative case

A G O : A Sub O : Imp O ... expand this and make it look good. Maybe can have A I O ... but then A must be in vocative case

In the béu linguistic tradition, a clause that has one R verb in it, or one N verb, or one I verb is called aʒiŋko baga or a simple clause. Any clause that has an R verb plus an G or N, verb is called a aʒiŋko kaza or a complex clause.

..... To think about

Further uses of the "s" form of the verb. That is the subjunctive.

Also used in dependent clauses with the meaning ...

that xxx should yyy.

Used after "want/hope/believe ?" if the subject is different. If subject is the same then the verb is in the gomia form.

hear, see, think, like, remember, know, believe | use tà + full verb with FACT complements.

hear, see, like, remember | use gomia with ACTION complements (English would use "-ing")

Sometimes when English would use the "to" construction, béu would use the -u participle | remember

Some rubbish

gwoi = to jump (involuntarily), to give a start

gwamoi = to make somebody jump, to give somebody a start

doika = walk

damoika = to manage, to run ......... damoikanai = "the management" or "the managers"

poma = leg

pomas = to kick, pomari = I kicked

pomaswan = liable to kick, fond of kicking

pomonda = good to kick

klonda = worth seeing

To fix up this bit.....Of course we can make two clauses, and have the second clause one element inside the first clause. To do that you must use the particle tà. Equivalent to one of the uses of "that" in English. tà basically tells you that the following clause should be treated like a single element, like a single noun.

I should mention sá tà ...

solbe = to drink

heŋgo = to live (or it could mean "a life")

soŋkau = to die (or it could mean "death")

glabu = person

moze = water

moʒi = steam

heŋgola = alive, living

soŋki = dead

..... Examples of prepositions

move these somewhere else

ilai = between

geka = without

mú = outside of

muka = outside

pika = inside

pòi = to enter or to put in

poi.a nambo = go into the house

wi.a toilia di toilicoipi = put these book in the bookcase ... wi.a toilia di toilicoin ... yeah, I like the second version

toilia di TAKE.ia poi.a nambo = take these book into the house

toilia di TAKE.ia nambo.pia jene.kye.a = take these book into the house and give to Jane

TAKE.iya toilia di nambo pireu jene kyireu = take these book into the house and give to Jane

méu = to exit or to take out ... I guess cat must be mèu

miwa nambo báin = come out of the house, get out of the house

.... -GO

| pronounced | operation | label | example |

| -go | noun => adjective, plus adjective => adjective, plus verb => adjective | "ish" | gla.go = effeminate, hia.go = reddish, bla.go = quarrelsome |

-go

gó = to resemble, to be like

gó dó = to be the exact image of

gla.go = effeminate, hia.go = reddish, bla.go = quarrelsome

Sometimes the -go derived words have negative connotations, as in gal.go

There is a suffix -ka (notice it is not considered a pilana), that often has a positive connotation, sometimes making a couplet with a -go derived word. For example ;-

gla.ka = womanly

kài = to appear, to seem

kò = appearance

..... Opposite meaning, same word class

The prefix for adjectives is "u"

taitau = many

utaitau = few

mutu = important

umutu = unimportant

The prefix for adverb is "u"

nan = for a long time

unan = not for a long time

The prefix for nouns is "u"

mezna = to fight

meznana = combatant

umeznana = non-combatant

As in English, not found that often. Sometimes found in rule books.

However the prefix for verbs is "ku"

| kunja | to fold | kukunja | to unfold |

| laiba | to cover | kulaiba | to uncover |

| fuŋga | to fasten, to lock | kufuŋga | to unfasten, to unlock |

| benda | to assemble, to put together | kubenda | to take apart, to disassemble |

| pauca | to stop up, to block | kupauca | to unstop |

| sensa | to weave | kusensa | to unravel |

| fiŋka | to put on clothes, to dress | kufiŋka | to undress |

| tasta | to tangle | kutasta | to untangle |

Note ... if they verbal prefix was simply u, then the same word would mean both "non-folding" and "unfolding"

kunja = to fold

kunjana = "folding" (an adjective) or "one that folds" (a noun)

kukunjana = "unfolding" or the "unfolder"

ukunjana = "non-folding" or "one that doesn't fold"

..

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences