Béu : Stuff discarded 3

..... Transitivity and the useful word "á"

..

In béu a verb is either transitive or intransitive. There is no "ambitransitive verbs as in English.*

For example ... in English, you can say ... "I will drink water" or simply "I will drink"

The second option is not allowed in béu ... as "drink" is a transitive verb, you must say "I will drink something" = solbaru á

Well actually you can, the á can be dropped ... just as easily as the pás is dropped. The point is that the listener "knows" that there are always 2 arguments. The same can not be said in English when you here "he drinks" ... it could mean that the subject habitually drinks alcohol, in which case we have only one S argument.

For another example ... in English, you can say ... "the woman closed the door" or simple "the door closed".

The second option is not allowed in béu ... as "close" is a transitive verb, you must say "something closed the door" = pintu nagori ás

(Actually there is another option for expressing the above ... you can change any transitive verb to an intransitive verb ... pintu nagwori = "the door was closed"

..

If an argument is definite in béu it is usually comes before the verb, and if indefinite it usually comes after the verb.

Now the word é is by definition indefinite. It actually means "somebody" OR "something". What happens if this word is put before the verb.

Well something quite interesting happens ... é changes into a question word meaning "who" or "what"

For example ... és pintu nagori = Who/what closed the door

For another example ... "what will I drink" = é solbaru

And yet another one ... "who drank the water" = és moze solbori

..

*Actually you can tell the transitivity of a verb (for a word of more than one syllable) by looking at its last consonant. If the last consonant is j b g d c s k or t then it is transitive. If it is ʔ m y l p w n or h it is intransitive.

There is about 300 words that have an intransitive form as well as a transitive form, only differing in their final consonant. The relationship between these final consonants is shown below. x means "any vowel".

| transitive | intransitive |

| -jx | -lx |

| -bx | -ʔx |

| -gx | -mx |

| -dx | -yx |

| -cx | -wx |

| -sx | -nx |

| -kx | -hx |

| -tx | -lx |

..

NB ... y and w are usually not allowed to be the second element in a word ... but in these special words, they are.

..

..... The conditional

iba = condition, stipulation

ibla = if .... occasionally the form ibala is used. When the longer form is used, it is showing that the speaker has a lot of doubt as to whether the eventuality will actually come to pass.

jú = then ... this is a conjunction, indicating that what follows follows on from what is before. That is, it shows that they are connected, part of the same train of thought or chain of actions.

The béu form for the conditional is .... ibla xxx xxx xxx jú xxx xxx xxx

Usually the tense of the verbs in the above two clauses is the future tense, but it does not have to be. Sometimes you can get quite complicated conditional linkages.

The irrealis form of the verb is also quite common in the conditional construction. For example ....

"If you had come to London, we would have met"

..... Arithmetic

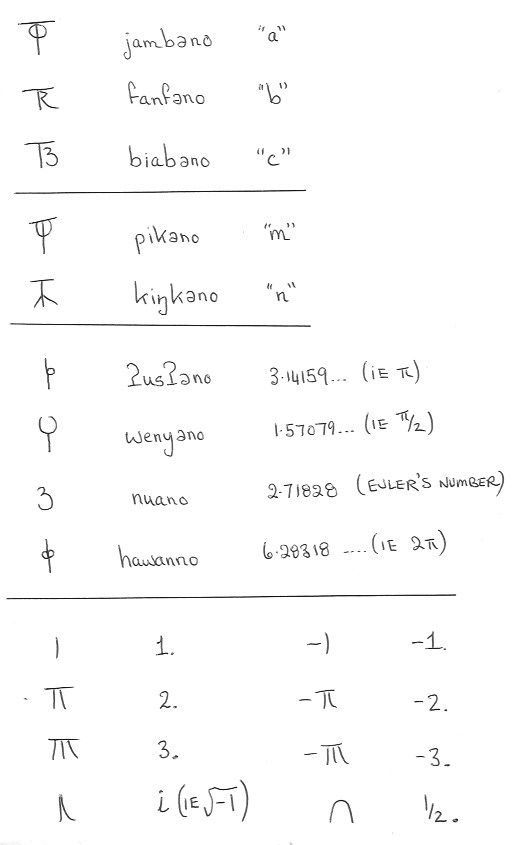

And just as béu has a special set of symbols for variables, it has a set of symbols for constants.

jambəno, fanfəno and biabəno are equivalent to our "a", "b" and "c".

The further set pikəno and kiŋkəno can be said to be "m" and "n"

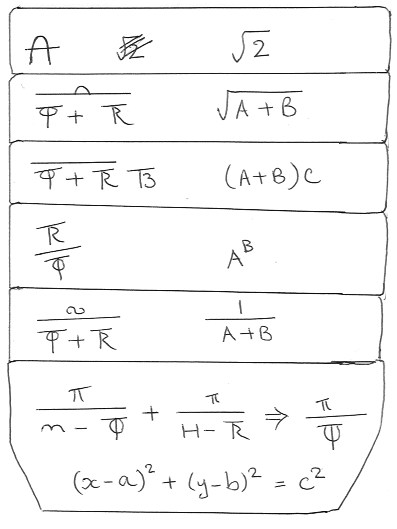

And finally down below I have given some other algebra bits from béu ... if anybody cares to decipher it.

Note ... In the above you will notice new symbols for "one", "two" and "three". These are invariable used in a mathematical context when these numbers appear in isolation and not as part of a number string (and the symbols for "one", "two" and "three" given in the earlier section on arithmetic, are invariably used in a body of prose ... the numbers are NEVER written out in full )

..

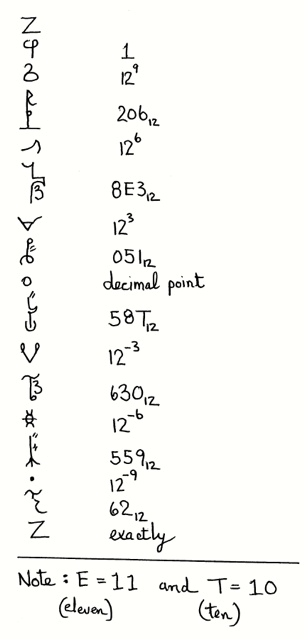

nogau = arithmetic

In the above table you can see how the symbol for the numbers 1 to 11 are derived. In the first column are how the numbers are pronounced in béu. In the second column is the symbol used for the single consonant which exists in the heart of every number. In the third column you can see how this consonant is modified slightly to produce the symbol used for each number. All these number symbols have a "number bar" extending from the top of the symbol towards the right. Only the first number in a string will have this "number bar".

On the left you can see how the symbols for the numbers -1 to -11 are derived. As you can see for the negative numbers there is a number bar extending from from the top of the symbol towards the left.

Notice that the forms for 1, 6, 7 and 9 have been modified slightly before the "number bar" has been added.

aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dù

Which is => 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... E represents eleven and T represents ten ... remember the number is in base 12.

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only ... if you can handle this number you can handle any number.

Now the 7 "placeholders"* are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. Used in the same way that we would say "point" or "decimal" when reeling off a number.

One further point of note ...

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say auvaidaula nàin .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say yanfa elaibau .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630 volts" instead of "630 microvolts".

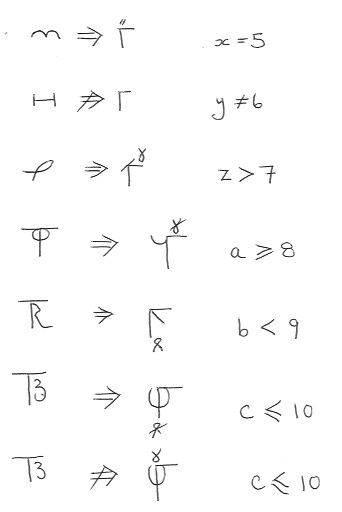

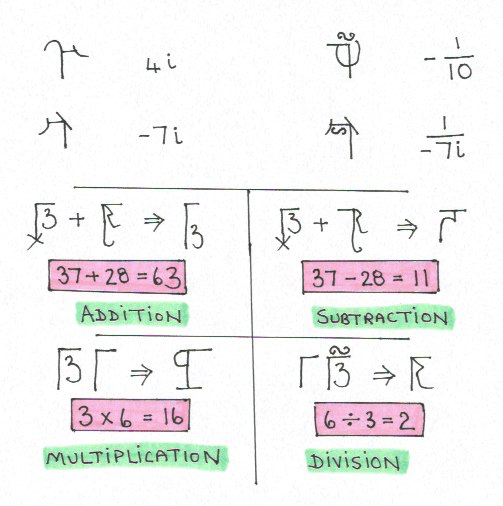

In the table above is shown the method for writing imaginary numbers and fractions.

Also the method of laying out the 4 basic arithmetic operations are shown.

A number can be made imaginary by adding a further stroke that touches the "number bar". And to get a fraction, you add a stroke just above the number. This stroke looks a bit like a small "8" on its side.

Notice that there is a special sign to indicate addition (+), and also a special sign for equality (=>).

As you can see above, there is no special sign for the multiplication or division operation. The numbers are simply written one beside the other.

Division is the same as multiplication except that the denominator is in "fractional form".

-6 is pronounced komo ela ... komo meaning left or negative.

By the way bene means right (as in right-hand-side) or positive.

4i is pronounced uga haspia** ... and what does haspia mean, well it is the name of the little squiggle that touches the number bar, for one thing.

-4i is pronounced komo uga haspia

-1/10 is pronounced komo diapa

i/4 is pronounced duga haspia

*Actually these placeholder symbols are named after 6 living things. This does not lead to confusion tho'. When you are doing arithmetic these concrete meanings are totally bleached.

**This can also be pronounced as bene uga haspia. However usually the bene bit is deemed redundent.

..

Nouns of position

pilana 1, 3 - 8 plus tài and jáu never occur unless preceding a NP or suffixed to a noun. However they can become nouns in their own right, if the affix ʔai is attached. For example …

piʔai = interior

Occasionally you get them joined to -ʔau. For example …

piʔau = interior surface

là can also be joined to -ʔau. For example …

laʔau = on it

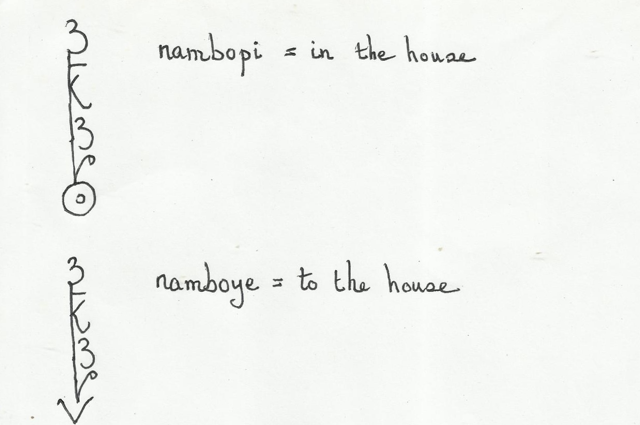

Note ... piʔai wò nambo means exactly the same as nambopi. Invariably the terser form is used.

Now no pilana can be a noun in its own right. They must always appear either suffixed on to a noun or standing in front of a NP. Now béu usually likes to drop the topic. But how can we drop the topic when we need no give a location with respect to a certain noun (which is the topic. Consider the English sentence ...

"They were in dire straits, in front the deep blue sea, behind the murderous viking raiders"

In the above sentence "in front" is a noun, as is "behind".

In béu, tài or jáu (and any of the pilana) can not be a noun, but by adding the suffixes ʔau (meaning "area"),ʔai (meaning "volume") and ʔa (meaning "side") the first 8 pilana plus tài and jáu can stand alone as nouns.

The above 3 suffixes obviously relate to a 1 dimensional scenario, a 2 dimensional scenario, and a 3 dimensional scenario. However we are not weightless beings floating in the matheverse but earthbound humans. For that reason we usually come across the forms ...

| piʔa | interior |

| mauʔa | above |

| goiʔa | under |

| taiʔau | the frontside |

| jauʔau | the backside |

| laʔau | the surface |

| ceʔau | the near side |

| duaʔau | the far side |

| beneʔau | the right hand side |

| komoʔau | the left hand side |

pilana 1, 3 - 8 plus tài and jáu never occur unless preceding a NP or suffixed to a noun. However they can become nouns in their own right, if the affix ʔai is attached. For example … piʔai = interior Occasionally you get them joined to -ʔau. For example … piʔau = interior surface là can also be joined to -ʔau. For example … laʔau = on it Note ... piʔai wò nambo means exactly the same as nambopi. Invariably the terser form is used.

..... How A O and S arguments are identified

1) báus glaye nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman (the woman is known to the addressee and (probably) known to the speaker)

If a noun comes after the main verb, then it is indefinite. For example ...

2) báus nori glaye alha = the man gave flowers to a woman (the woman is unknown to the addressee, whether she is known to the speaker is unspecified)

béu also has two other kinds of indefinite ...

3) báus nori yé é glà alha = the man gave flowers to some woman (the woman is unknown to the addressee and unknown to the speaker)

4) báus nori yé glà fana alha = the man gave flowers to a certain woman (the woman is unknown to the addressee but known to the speaker)

In this section we discuss pronouns and also introduce the S, A and O arguments.

béu is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings.

..

In English there is a fixed word order, which also helps to tell who did what to who when the participants are given as nouns instead of pronouns. In béu the order of the verb and the participants are not fixed as in English.

..

glàs baú timpori = The woman hit the man

glà baús timpori = The man hit the woman

It can be seen that "s" is added to the "doer" of the action.

..

However consider the clause below ...

..

glà doikor = The woman walks

It can be seen that the "doer" does not have an attached "s" in this case.

The reason is that "to walk" is an intransitive verb while "to hit" is a transitive verb

It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument.

It is the convention to call the "doer" in a transitive clause the A argument and the "done to" the O argument.

A language that has the S and O arguments marked in the same way is called an ergative language

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument).

In béu ò is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : ós is the "doer to"(A argument).

..

The passive construction

bwò is involved in the passive construction.

3) jonosA timpori jeneO = John hit Jane

4) jeneS bwori timpa (jonotu) = Jane was hit (by John)

4) is the passive equivalent of 3) ... used when the A argument is unknown or unimportant.

If the agent is mentioned, he or she is marked by the instrumentive pilana.

Notice that all the derived verbs are transitive. There are three ways that we can make an intransitive clause.

1) pintu tí mapori = The door closed itself ... this form strongly implies that there was no human agent. Possibly the wind closed the door (or a supernatural element when it comes to that).

2) pintu bwori mapau = The door was closed ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

3) pintu lí mapa = The door became closed ... this uses the adjective form of mapa and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

By the way, the G-form of nava "open" is navai

Let us go back to gèu and consider gèu in an intransitive clause. As above we have 3 ways.

1) báu tí geusori = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved.

2) báu bwori gèus = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

3) báu lí gèu = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of gèu and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

Notice that naikes means the same as kyé sau naike (to give to be sharp) ... but why say this mouthful when you can simply say naikes.

Any single syllable adjective, must have the suffix du in all its verbal forms. For example ;-

àus = to blacken, maŋkeu = faces

ausuri maŋkiteu = they blackened their faces ... interesting construction ... we use the transitive form even tho' they perform the action on themselves.

Verb chains

Even though the gomia can be considered proper nouns, they obey different rules of syntax compared to normal nouns.

They never have the -s suffix (perhaps they can have the sá preposition).

We have already discussed the type B noun phrase that they can part of.

They do not take all the pilana. However they occur with ge and ji quite a lot. Corresponding to "by" and "in order to/to".

He passed his exams "cheat".ge = He past his exams by cheating

He went to the river "swim".ji = He went to the river to swim.

They also occur with n and ho however the meaning that these suffixes add are a bit different with gomia.

When n is added to gomia it means that the verb is a second or later verb in a verb chain. The tense, aspect and evidentiality is the same as the initial verb. Also the subject (i.e. S or A) is the same as the subject of the initial verb.

When ho is added to gomia it means that the verb is a second or later verb in a verb chain. The tense, aspect and evidentiality is the same as the initial verb. Also the subject (i.e. S or A) is the same as the object of the initial verb.

This is used when things happen at the same time and the subject of all the verbs is the same. Notice that the n-forms can come after the r-form verb.

It is not really important which verb comes first, perhaps the one considered the most relevant/important should come first.

The three verbs above sort of amalgamate into a single verb. The actions should be considered a single event.

In the examples above the three constituent verbs of the verb chain happen at the same time but this is not always the case. In the example below the constituent verbs happen one after the other.

aus hufu báin kyén jonok = Take the sheep and give it to John.

Word building when it comes to verbs ....

béu has verb “chaining”. In verb “chaining” the first verb has its full complememt of person, tense/aspect and evidentuality.

However all verbs that follow the initial verb are in their gomia form. They have the pilana -n affixed if the A or S argument of the initial verb, is the same as the A or S argument of gomia.

They have the pilana -ho affixed if the O argument of the initial verb, is the same as the A or S argument of gomia. The tense/aspect and evidentuality is the same as the initial verb.

bawas bura nambo laulan halfan => The men go home singing and laughing

bawas bura nambo laulan lauloi halfan => The men go home singing songs and laughing

bawas bura nambo laulan halfan jonowo => The men go home singing and laughing about John

Note that if halfa was a noun, we would have to say nà halfa jonowo. If laula was a noun, we would have to say nà laula lauloi ???

This is used when things happen at the same time and the subject of all the verbs is the same.

In the above case it is not really important which verb comes first, perhaps the one considered the most relevant/important should come first.

The three verbs above sort of amalgamate into a single verb. The actions should be considered a single event.

In the examples above the three constituent verbs of the verb chain happen at the same time but this is not always the case. In the example below the constituent verbs happen one after the other.

aus hufu báin kyén jonok (take sheep go give John) = Take the sheep and give it to John.

Some examples ;-

kàu = to come {∅} {∅, fi} {∅, k} {∅, fi, k} {∅, n}...where the "n" argument qualifies a time ... I suppose we have to call this an intransitive verb.

bái = to go {∅} {∅, fi} {∅, k} {∅, fi, k} {∅, n}...where the "n" argument qualifies a time

klói = to see {s, ∅} ... I suppose we have to call this an transitive verb.

to scatter {s, ∅} {∅}

break {s, ∅} {∅}

break the ice and scatter it

break and scatter the ice

I went and saw him/her => bari ò klóin (could it be kari klóin ò ?? )

I saw her and went => klari ò báin (could it be ò kari klóin ?? )

I saw her and she went => klari ò baiho ... can only be said if it is part of a recognized process.

How are the case frames for the below ???

gàu = to descend, to go down, to let down {∅}, {s, ∅}, {∅, n}, {s, ∅, n} ... 4 case frames are are commonly used with gàu. Actually there are other case frames possible. For example {s,∅,n,k} as in "I lowered John down the cliff-face to the ledge", but this 5th case frame is judged too uncommon to mention.

jompai = to rub {s, ∅}

jompai gauho = to erode {s, ∅} ... this is a lexeme made up of two non-adjacent words. In a lexeme made with the -ho element, the word order is always important.

In this case the case frame of the compound word follows the case frame of the original word.

WORK OUT CASE FRAMES FOR OTHER COMPOUNDS.

Also we have a compound gomia form, gaujompai meaning erosion.

DO WE ALWAYS GET COMPOUND GOMIA FORMS ??

You would say "The rain erodes the mountain-range" rather than "The rain rubs the mountain-range down" because the "real" meaning of "rub" involves something solid against a something rigid. ??

You can add as many verbs as you want.

passora singau kite flyau = He is passing by singing and flying a kite

WHAT ABOUT SEPERATE OBJECTS ON THE TWO VERBS ?

WHEN WE INTRODUCE "ALONG" (FOR EXAMPLE) WE ARE INTRODUCING A NEW OBJECT IN THE CLAUSE ??? The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in béu anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)".

láu = to become

I painted the house red = saisari nambo lauho hìa

I painted the house naked = saisari nambo sàun naked .... I painted the house naked

I whistled while I walked = wizari doikan or you could say wizari saun doikala or because doikala is an adjective, if placed directly after a verb, it acts like an adverb => wizari doikala

to whistle = wiʒia

I saw John whistling = klari jono wiʒila

awari yanfa ploiho nambo => I put the rabbit in the house ????

The causative construction

(pàs) dari jono dono = I made john walk

(pàs) dari jono timpa jene = I made John hit Jane ... in this sort of construction, jono, timpa and jene must be contiguous and jono should be to the left of jene.

..... Movement

The 3 below examples are the commonest situation ....

lái london = to go to London ... this is not a SVC..................(here)...x--------------------> London

lái pobo = to go to the forest ... this is not a SVC

lái twè jono = to go to meet John = to go to John

And the 3 examples are also common ....

data cía london = to come from london................................(here)...<--------------------x London

data cía pobo = to come from the forest

data cía jono = to come from John

The 3 examples below rare ... "to come to London" is in contrast to "to come to England" or "to come to Notting Hill" but if this distinction is not needed, then "to come" is sufficient.

data dèu london = to come to London.............................................x--------------------> London (here)

data dèu pobo = to come to the forest

data twè jono = to come to meet John

The below examples are rarer still .... in most situations, simply "to go" would be sufficient.

lái cía london = to go from London = to leave London.....................<--------------------x London (here)

etc. etc.

..... Verb chains

A verb chain must have all the verbs contiguous. However sometimes there can be 2 (or more) objects. When 2 objects are present the noun-incorporation must be used. This is done simply by sticking the object to the front of the verb to make one word.

2) ALL EVENING CHAMPAIGN.DRINK-I CAVIAR.EAT-AIR = All day we were drinking champaign and eating caviar.

3) ALL AFTERNOON REPORT.WRITE-I PHONE.ANSWER.AR = All afternoon I was writing reports and answering the telephone.

The internal time structure of the chain must be worked out from knowledge of the situation described. For example in 1) the actions were CATCH then COOK then EAT in that order (probably). In 2) the actions DRINK and EAT happened at the same time (probably). In 3) the 2 actions wouldn't be at the same time but interspersed sort of randomly through-out the afternoon (probably).

Now all the above were examples of "one off" verb chains. These are relatively rare. More often one comes across the common verb chains. For example ...

4) CLIMB-I DESCEND TREE = to climb down a tree

5) THROW-I DESCEND BOOK = to throw down a book

6) THROW-I DESCEND-I US.COME BOOK = to throw down a book at us (it didn't hit us)

7) THROW-I DESCEND-I US.ARRIVE BOOK = to throw down a book at us (it hit us)

Note ... Another place where noun-incorporation is used a lot is with the participles. For example ...

DEER.HUNT-ANA = deerhunting, deerhunter

..... A discussion of English participles

..

Now English has two participles, the "active participle" and the "passive participle".

They appear as adjectives (of course, an adjective derived from a noun is the definition of "a participle"), however both forms also appear in verb phrases. If you are given a clause out of context it is sometimes impossible to tell if the participle is acting as an adjective or as part of a verb phrase. For example ... first the "active participle" ...

1) The writing man

2) The man is writing

3) The man is writing a book

In 1) "writing" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "writing" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The man is green a book" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "is writing" is a verb phrase (one that has given progressive meaning to the verb "write"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "is writing" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

... now the "passive participle" ...

1) The broken piano

2) The piano is broken

3) The piano was broken

4) The piano was broken by the monkey

In 1) and 2) "broken" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "broken" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 3) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 4) ... No not an adjective "The piano was green by the monkey" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 4) is that "was broken" is a verb phrase (one that has given passive meaning to the ambitransitive verb "break"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 3). The proper analysis of this could be that "was broken" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 3) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations* when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

*The five-week deadlock between striking Peugeot workers and their employer was broken yesterday when the management obtained a court order to end a 10-day sit-in at one of the two factories in eastern France, Sarah Lambert writes.

I would say either analysis is valid for the above sentence.

..

..... Copula's

..

The word copula comes from the Latin word "copulare" meaning "to tie", so a copula is a verb that ties. In béu(as in other languages) they differ from normal verbs in that they are quite irregular.

Also in béu a copula clause taiviza requires a specific word order and the s (the ergative case) is never suffixed to any noun, as normally happens when a verb is associated with two nouns.

... jìa

jìa is the béu main copula and is the copula of state. It is the equivalent of "to be" in English, which has such forms as "be", "is", "was", "were" and "are".

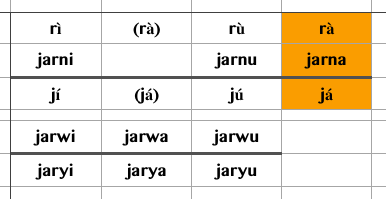

The table below echoes the second table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In three rows (the second and the two at the end) the copula includes the subject marker. In the table a representing first person singular is given. In rows 1 and 3 the copula does not include the subject marker (so obviously when these form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedent word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or já followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Actually rà is usually dropped completely.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... gí já moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... pá rà moltai = I am a doctor

Another situation where rà tends to be used is when either the subject or the copula complement are longish trains of words. For example ...

solboi alkyo ʔá dori rà sawoi = Those alcoholic drinks that she made are delicious.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

... làu

làu is the béu is the copula of change of state. It is the equivalent of "become" in English.

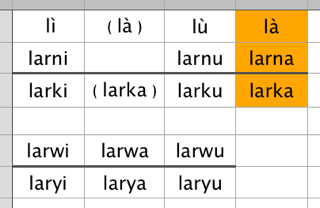

Again the table below echoes the table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In four rows (the second, third and the two at the end) the copula includes the cenʔo. In the table the a of the first person singular is given. In the first row the copula does not include the cenʔo (so obviously when this form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedant word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or ká followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

As you can see this copula is more regular than the main copula.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

làu haube = to become beautiful OR to become a beautiful woman

... The copula of existence

Some languages have a verb to indicate that something exists. twái

This usually introduces a new protagonist in a narrative. The new protagonist is by definition, indefinite. For example ...

twor glá gáu ʔaiho = There was an old and ugly woman

Often it is used with a phrase of location.

nambopi twuru aiba glabua = There will be three people in the house .... 3 people are in the house ???

There is no word that corresponds to "have". The usual way to say "I have a coat" ...

pán twor kaunu = "at me exists a coat"

olwa = to exist

elya = to not exist

??????????????????

há = place

dí = this

dè = that

While you sometimes come across the há dí the word hái is the usual way to express "here".

In a similar manner you sometimes come across the há dè the word ade* is the usual way to express "there".

*This word is an exception to the rule that inside a word and between vowels, d can be either pronounced as "d" or "ð". In ade the d is always pronounced "ð".

There is a house = A house exists = ade (rà) nambo

This is patterned on the more general locative construction.

In the apple tree is a beehive ????

ade pona paye = "I feel cold" ... maybe against expectations ... no reason to think that other people would be cold.

ʃi pona = "It is cold" ... everybody should feel cold

..

... 8 co-ordinates

There are 6 suffixes, that when attached to a noun, make an adjective.

nambo = house

nambokoi = above the house

nambobeu = below the house

nambofia = this side of the house ... béu speakers, if a building is in side, prefer to specify a position w.r.t. their own position, and not to what is called "front" my convention.

nambopua = the far side of the house

namboʒi = to the left of the house

nambogu = to the right of the house

Also there are 2 suffixes, that when attached to an infinitive, make an adverb.

solbe = "to drink" or "drinking"

solbetai = before drinking

solbejau = after drinking

Now in an infinitive phrase the constituent order is Subject Object Infinitive, so ...

moze solbetai jonos CHECKED THE GLASS WAS CLEAN = Before drinking the water, John checked that the water glass was clean.

Also we have the constructions ...

moze solben jono KEPT AN EYE OUT FOR TIGERS = While drinking water, John kept an eye out for tigers.

jono moze solbewe I DRINK BEER = I drink beer like John drinks water

..

..... The pilana

..

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON are called "cases". The classical languages, Greek and Latin had 5 or 6 of these. Modern-day Finnish has about 15 (it depends on how you count them, 1 or 2 are slowly fading away). Present day English still has a relic of a once more extensive case system : most pronouns have two forms. For example ;- the third-person:singular:male pronoun is "he" if it represents "the doer", but "him" if it represents "the done to".

The 12 béu case markers are called pilana

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana <= (pila + ana), in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle". It is an adjective which means "putting (something) in position".

As béu adjectives freely convert to nouns*, it also means "that which puts (something) in position" or "the positioner".

Actually only a few of them live up to this name ... nevertheless the whole set of 12 are called pilana in the béu linguistic tradition.

..

..

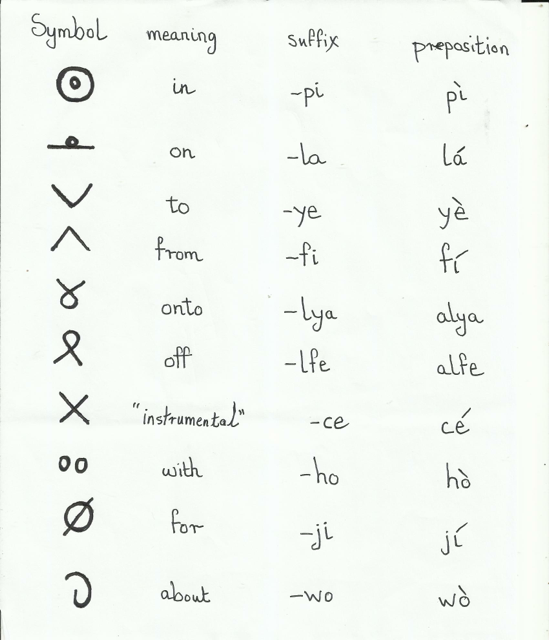

The pilana are suffixed to nouns and specify the roll these nouns play within a clause.

As well as the 10 illustrated above, we have s for the ergative case and n for the locative case. Also we have the unmarked case which represents the S or O argument.

sá and nà are the free-standing variants of -s and -n.

The pilana specify the roll that a noun has within a clause. However both the ergative case and the locative case (and a few other cases) can specify what rolls a noun has within a NP.

For example nambo pàn = "a/the house at me" or "my house"

timpa báus glà = the man's hitting of the woman ... this is an example of an infinitive NP.

letter blicovi = the letter from the king

pen gila = a pen on your person

As shown above the pilana are represented by their own symbols. Or at least the ten that do not consist of single letters.

For the suffix form of the first 2 and last 2 symbols given above, the end of the word proper "touches" the symbol. For the other 6 symbols, the word proper "impinges" upon the symbol. See below ...

..

..... Rules governing the pilana

..

Now one quirk of béu (something that I haven't heard of happening in any natural language), is that the pilana is sometimes realised as an affix to the head of the NP, but sometimes as a preposition in front of the entire NP. This behaviour can be accounted for with thing with two rules.

1) The pilana attaches to the head and only to the head of the NP.

2) The NP is not allowed to be broken up by a pilana. The whole thing must be contiguous. So if a NP has elements after the head the case must be realised as a preposition and be placed in front of the entire noun phrase.

3) No two pilana can be stuck together (WOULD THIS EVER HAPPEN ??)

So if we have a NP with elements to the right of the head, then the pilana must become a preposition. The prepositional forms of the pilana are given on the above chart to the right. These free-standing particles are also written just using the symbols given on the above chart to the left. That is in writing they are shorn of their vowels as their affixed counter-parts are.

Here are some examples of the above rules ...

..

fanfa = horse

sonda = son

blico = king

fanfa sondan = the horse of the son

sonda blico = the son of the king

However the suffixed form can only be used if the genitive is a single word. Otherwise the particle na must be placed in front of the words that qualify. For example ;-

We can't say *fanfa sondan blicon however. The -n on sonda is splitting the NP sonda blico.

So we must say fanfa nà sonda blicon

Some more examples ...

fanfa nà sonda jini blicon = "the horse of the king's clever son

fanfa nà sonda nà blico somua = "the horse of the fat king's son"

Here are some more examples of the above rules ...

pintu nambo = the door of the house

pintu nà nambo tuju = the door of the big house

When one of the specifiers is involved we have two permissible arrangements.

1) pintu á nambon= the door of some house

2) pintu nà á nambo = the door of some house

1) is the more usual way to express "the door of some house", but 2) is also allowed as it doesn't break any of the rules.

This also goes for numbers as well as specifiers.

papa auva sondan = the father of two sons

papa nà auva sonda = the father of two sons

..

*Another case when the pilana must be expressed as a prepositions is when the noun ends in a constant. This happens very, very rarely but it is possible. For example toilwan is an adjective meaning "bookish". And in béu as adjectives can also act as nouns in certain positions, toilwan would also be a noun meaning "the bookworm". Another example is ʔokos which means "vowel".

The pilana and the relative clause

We have already seen that the final element of a NP can be a relative clause and we introduced the two particles à and às : corresponding to "who" and "whom".

Actually the basic relativizer is à and -s is the ergative case marker. The other case markers (well most of them) can also be suffixed to the à relativizer.

àn quite a common relativizer also.

Remember when we talked of the NP before we said a genitive (or a locative) can go as the last element in the adjective slot. For example ...

nambo jonon = John's house

However if the element that must become the genitive is longer than one word, the relativizer àn must be used. For example ...

nambo àn báu jutu = The big man's house.

WAIT ... HOW DOES THIS SQUARE UP WITH THERE BEING TWO FORMS OF THE "N" CASE .... SUFFIXING FORM AND FREE STANDING FORM ??

"the man ate the apple on the table" ... ambiguous in English

ALL THE BELOW SHOULD BE AFTER THE PILANA IS INTRODUCED

the basket api the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman aye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town avi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad à alya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.*<-sup>

the boat à alfe you have just jumped is unsound.*<-sup>

báu ás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

nambo àn she lives is the biggest in town.

Note ... The man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man that own dog that I shot, reported me to the police

báu aho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife age he severed the branch is a 100 years old

The old woman aji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy aco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

..

..... Definiteness

..

An interesting concept ... let us think about how English handles it.

..

The béu definite/indefinite

..

Well the person you are talking to is the person you want to impart the message to (the second person), so basically whether you use "a" or "the" will dependent on the addressee's knowledge of the relevant NP. For example ...

..

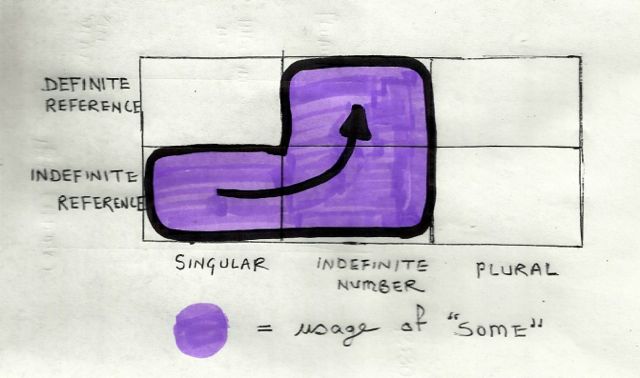

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | |

| I car want buy | 1 |

| I want buy car | 0 |

And to show that the speaker does not have a particular car in mind either he would say "I want buy some car"

but of course he would have some minimum requirements, if he had no minimum requirements he would say "I will buy any car"

..

The use of é is very like the use of "some" in English ... a bit of doubt as to whether it makes the NP definite for the 1st person or for the 3rd person.

..

Usage of "this" and "that"

???

3) unknown to speaker but known to listener ... "that dog that bit you yesterday was put down" .... or equally valid ... "the dog that bit you yesterday was put down"

The question here is, of course, if the dog is "totally" unknown to the speaker ... why is here speaking about it ... ah, we must go deeper

Or consider this Norwegian, getting more definite in six easy steps.

5) She wants to marry a Norwegian ............. Could be any Norwegian. "She" does not even have any definite Norwegian in mind.

6) She wants to marry a Norwegian ............. Unknown to speaker and listener. But "she" has her eye on a particular Noggie.

7) She wants to marry some Norwegian ..... Not any Norwegian but the speaker known very little about him and the listener nothing.

8) She wants to marry a Norwegian** ........ Known to speaker but unknown to listener

9) She wants to marry this Norwegian ........ Known to speaker but unknown to listener

10) She wants to marry that Norwegian ....... Known to speaker and listener

9) and 10) can be said to be "half-definite" (my own term) The Norwegian is known but as a sort of peripheral character that hasn't as yet impinged on the consciousness* of the interlocutors that much. As/if he becomes more into focus in the interlocutors lives he will, of course, become, the Norwegian (or more probably Oddgeir or Roar or what have you).

The use of this and that for "half-definite" makes sense ... it is iconic. "This thing" is near the speaker hence seen, touched, smelt by the speaker ... known to the speaker.

"That thing" is out in the open, hence experienced/known to both speaker and listener.

*Or the world-model that we each build up inside our heads.

**Notice that "She wants to marry a Norwegian" is ambiguous ... it could either have the implications of either 5), 6) or 8).

But enough of English. béu makes a noun more definite by putting it further to the left. To have an obligatory a or the in front of every noun is wasteful. However non-obligatory particles (such as "some" are fine)

Basically if a noun or noun phrase is to the left of the verb* it is definite, if it is to the right it is indefinite. For example ;-

báus timpori glà = The man hit a woman

glà timpori báus = A man hit the woman

However this rule does not effect proper names and pronouns. They are always definite so they can wonder anywhere in the clause and it doesn't make any difference.

*When I say verb here I am not counting the three copula's. They always have the order

Copula-subject copula copula-complement

Also dependent clauses have fixed word order ???

..

Some original thought on "a" and "the"

..

Well the person you are talking to is the person you want to impart the message to (the second person), so basically whether you use "a" or "the" will dependent on the addressee's knowledge of the relevant NP. For example ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | |

| I bought the car | 1 |

| I bought a car | 0 |

..

In the above table I am using terminology from the subject of logic ... 1 = yes, 0 = no, X = yes or no

..

So this is the BASIC difference between definite and indefinite.

..

In the above example (because of the "situation") we can also say ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 1st person | ... when 1st person means the speaker of course | |

| I bought the car | 1 | |

| I bought a car | 1* |

..

* Logic makes this a "1" ... not the grammar

..

We can combine the two tables above ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | ... | Relevant NP known to 1st person | |

| I bought the car | 1 | 1 | |

| I bought a car | 0 | 1 |

..

Now lets change the "situation". We will change it as to its "reality" or 'realisation" ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | ... | Relevant NP known to 1st person | |

| I want to buy the car | 1 | 1 | |

| I want to buy a car | 0 | X *** |

..

But as we said at the start, the reason for saying something is to make the hearer understand, so the X given to the speaker is perfectly logical.

..

***The question will be asked "how to make unambiguous the speakers knowledge of the NP". Some ways are shown in the table below ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 1st person | ... when 1st person means the speaker of course | |

| I want to buy a certain car | 1 | |

| I want to buy this car ... | 1 | |

| There's a/this car (that) I want to buy. | 1 | |

| I want to buy a car, any car ... | 0 |

..

Now lets introduce a 3rd person.

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | Relevant NP known to 1st person | ||

| She married the American | 1 | 1 | |

| She married an American | 0 | X |

..

"She" of course being the 3rd person.

..

Now let's expand the above table a bit ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | Relevant NP known to 1st person | Relevant NP known to 3rd person | |||

| She married the American | 1 | 1 | 1 * | ||

| She married an American | 0 | X | 1 * | ||

| She married some American | 0 | 0 ** | 1 * |

..

* Logic makes this a "1" ... not the grammar

** Actually many connotations about the speakers attitude when "some" is used. When said "tensely" shows disapproval. When said "whistfully" shows speakers unhappyness with his lack of knowledge about the American. This is the marked case of the indefinite so I guess many many (or any ?) unusual point of view on the speakers part will be coded by "some".

..

Now lets change the "situation". We will change it as to its "reality" or 'realisation" ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | Relevant NP known to 1st person | Relevant NP known to 3rd person | |||

| She wants to marry the American | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| She wants to marry an American | 0 | X | X | ||

| She wants to marry some American | 0 | 0 | 1 |

..

So to summarise(and simplify) the above data, I would say ...

1) "the" or "a" chosen depending on whether the addressee (2nd person) knows the NP talked about

2) "some" is chosen over "a" to show that the NP is identifiable (but not necessarily by the 1st or 2nd person)

3) ... "some" also has picked up various connotations with regards to the 1st persons view of the NP under discussion.

A bit about "this" and "that"

The original meaning for these two, was when some object is unknown to the addressee but the speaker wants to make it known to the addressee. Typically he points (or gestures) to the object as he introduces it. He will qualify the object with "this" if it is near, and with the word "that" if it is not near.

Now in English, people have started using "this" when something is not in sight. It is used to indicate that the object is known to the speaker but not known to the addressee.

Probably the commonness of the above has prompted people to start saying "this here" instead of "this" by itself.

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences