Béu : Chapter 2

..... The parts of speech of béu

"Parts of speech" is linguistic jargon, which is referring to the different "classes" of words a language might have. For example "nouns", "verbs", etc. etc.

In fact nouns (N), verbs (V) and adjectives (A) are the big three, and after some debate over the last 30 years, it has been agreed that every language has these three word classes.

In béu a noun is called cwidau (cwì meaning a physical object), a verb is called jaudau (jàu meaning "to move"), and an adjective is called saidau (sái meaning "a colour").

There are other classes of words in béu as there are in other languages. béu has adverbs (wedau) but these don't really come into their own, being more a form an adjective takes in certain situations. Also a lot of words that are called adverbs in English are called particles (feŋgia) (F) in béu. Particles are a type of hold-all category for a word that doesn't fit into any of the other classes. Under the term "particle" many subclasses can be defined, and in fact some subclasses have a class membership of one. If you come across a word that can not easily be equated with any of the major word classes ... well then you probably have a feŋgi.

It is necessary to talk about another part of speech which i will refer to by the béu term gomia* (G). It is a form of the verb which is called the "infinitive" in the Western linguistic tradition.

* goma means "tail" and gomia means "tail-less". The reason for this is that a verb in a sentence functioning as verbs commonly do, has person, number, tense, aspect and evidentiality expressed on the verb as series of suffixes, hence the "tail". These items are not expressed on the gomia.

In contradistinction to gomia we have gomua (jaudau gomua to give the concept its full title) which is a verb in a sentence functioning as verbs typically do.

For example solbarin (I drank, so they say) is a gomua.

solbarin is built up from the gomia "solbe" ... first you delete the final vowel => then you add "a" meaning first person singular subject => then you add "r" meaning that the mood is indicative (as opposed to imperative or subjunctive) => then you add "i" meaning simple past tense => and finally you add "n" which is an evidential, meaning that the utterance is based on what other people have said.

solbarin is gomua pomo or "a full tail verb".

The three evidential markers are all optional, so they can quite easily be dropped. solbari (I drank) is what is called gomua yàu or "a long tail verb".

solbis (you lot drink) and solbon (let him drink) are gomua wái or "a short tail verbs" ... the first is an example of the imperative and the second is an example of the subjunctive (more linguistic jargon ... sorry).

solbai is called an part verb ???

..... Some linguistic terms in béu

By the way, while we are at it (defining linguistic terms)

nandau = word

semo = a clause ... from the verb "to say" sema

semoza = a sentence

jaudauza = a verb phrase or verb complex (commonly called a "predicate" by linguists). This is the verb together with the five modals.

feŋgi = a particle ... given above

plofa = a participle (P) ... there are 3 participles in béu

ʔasemo = a relative clause

kalope = a complement clause. There are three types of these ... kalope jù, kalope tà and kalope tavoi

A kalope jù is a gomiaza if it is more than one word long, if only one word long it is simply a gomia

A gomiaza can comprise of subject ... gomia ... object ... adverb ... other peripheral terms

The term gomuaza is not used. You would use the word semo meaning clause.

taifi (that which is to be tied ??? check participles) = copular subject

taifo = copular complement

taifau = to tie

taifana = a copula

..... How to ask a YES/NO question

To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a YES/NO answer), we stick the particle ʔái on the end of the sentence.

ʔái is neutral as to the response you are expecting. If you are expecting a positive reply, you would use the particle ʔaiwa instead.

If you were expecting a negative response, I suppose you would negate the sentence and then use ʔaiwa.

To answer a positive question, YES or NO ( ʔaiwa àu aiya ) is sufficient.

To answer a negative question positively, YES ( ʔaiwa ) is enough.

To answer a negative question negatively, you must speak an entire clause : or you can say "no" followed by an entire clause.

For example ;-

Statement 1) glà (rà) hauʔe ʔái = The woman is beautiful.

Question 2) glà hauʔe ʔái = Is the woman beautiful ? .......... If she is beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she isn't answer aiya.

Statement 3) glà (ká) hauʔe ʔái = The woman isn't beautiful.

Negative question 4) glà ká hauʔe ʔái = Isn't the woman beautiful ? ........ If she isn't beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she is answer aiya ò rà hauʔe. (notice that the copula must be used in this case)

( in a later section we will see that it is not always necessary to use ʔái. When you have a clause with a modal, you simply change the word order to ask a polar question. ) ???

Also it is possible to focus on a particular element when asking a YES/NO question in béu. This is done by putting the particle cù after the element that you want to focus on. For example ...

Statement 1) báus glàn timpi alhai = the man gave flowers to the woman

Straight question 2) báus glàn timpi alhai ʔái = did the man gave flowers to the woman ?

Focused question 3) báus glàn cù timpi alhai ʔái = Is it the woman that the man gave flowers to ?

..... How to ask a content question

To turn a normal statement into a content question we stick the particle cù at the beginning of the sentence. We must also represent the content we are looking for by an interrogative and put this interrogative right after the cù. The most common content interrogative is ʔái which means "what" or "which" or "who" (it depends on the context).

Notice that this is the same as the tag that we use to form a YES/NO question. Another use of this word is as a nominalizer. In fact this word is so common that a shorthand way is used to write it. cù also has a shorthand form. See below ...

ʔái takes pilana, just as a normal noun does. Here are some examples ...

Statement 1) báus glàn timpi alhai = the man gave flowers to the woman

Question 2) cù ʔáis glàn timpi alhai = who gave flowers to the woman

Question 3) cù ʔáis báus glàn timpi alhai = which man gave flowers to the woman

Question 4) cù ʔáin báus timpi alhai = to whom did the man gave flowers

Question 5) cù ʔáin glàn báus timpi alhai = to which woman did the man gave flowers

Question 6) cù ʔái báus glàn timpi = what did the man give to the woman

Question 7) cù ʔái alhai báus glàn timpi = which flowers did the man give to the woman

The other pilana are also possible ... and they follow the normal pilana affixing rules. For example ...

cù ʔái nambolna??? = onto which house did the bird land

cù alna ʔái nambo gì??? = onto which house of yours did the bird land

..... Pronouns

In this section we discuss pronouns and also introduce the S, A and O arguments.

béu is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings (in English there is a fixed word order, which also helps. In béu the word order is free).

timpa = to hit ... timpa is a verb that takes two nouns (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb).

pás ò timpari = I hit him pà ós timpori = He hit me ... OK in this case the protagonist marking in the verb also helps to make things disambiguous. But this will not always help, for example when both protagonists are third person singular.

So far so good. And we see that English and béu behave in the same way so far. But what happens when we take a verb that takes only one noun (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb). For example doika = "to walk". In English we have "he walked". However in béu we don't have *ós doikori but ò doikori (equivalent to saying "*him walked" in English). So this in a nutshell is what an ergative language is.

It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument. For example òS fomporta = She has tripped

It is the convention to call the "doer" in a transitive clause the A argument and the "done to" the O argument For example ósA timpori jeneO = He hit Jane

The S was historically from the word "Subject" and the O historically from the word "Object", but it is best just to forget about that. In fact when I use the word "subject" I am talking about either the S argument or the A argument.

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument).

In béu ò is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : ós is the "doer to"(A argument).

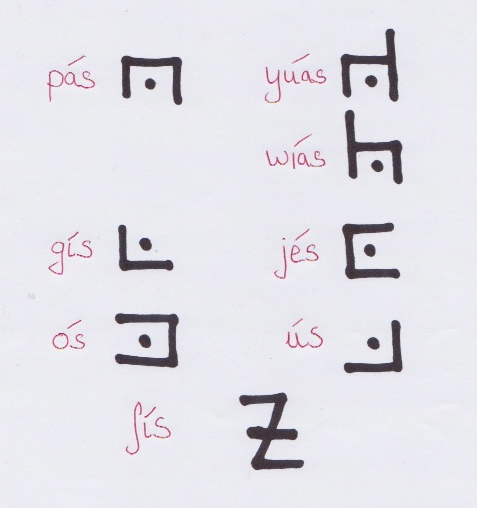

Below are two tables showing the two forms of the béu pronouns.

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | ús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

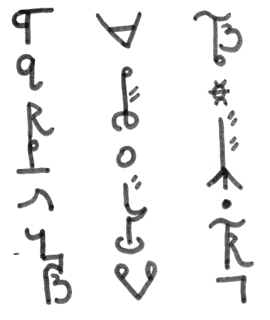

However these pronouns are hardly ever written out as above. There is a recognized "shorthand" method of writing them. This is shown below.

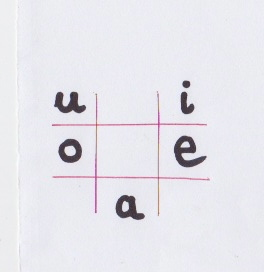

This method is based on the fact that all the pronouns have a different vowel sound (the ones that refer to humans anyway). A look at a béu vowel chart might let you work out what is happening here.

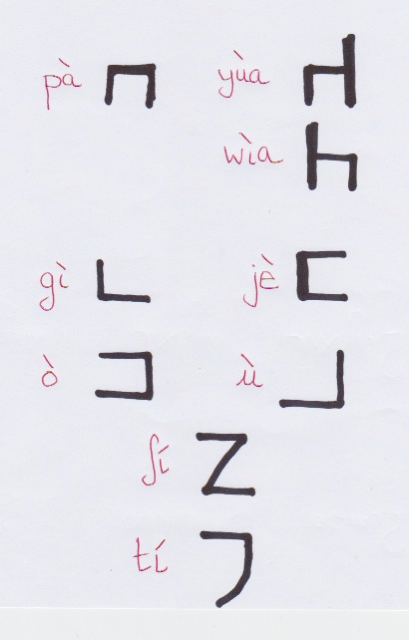

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | ù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

NOTE ... I made a mistake with the tone on ʃi above.

The table above shows the shorthand form for these non-ergative pronouns.

There could be another member it the above table. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves, a special particle tí is used.

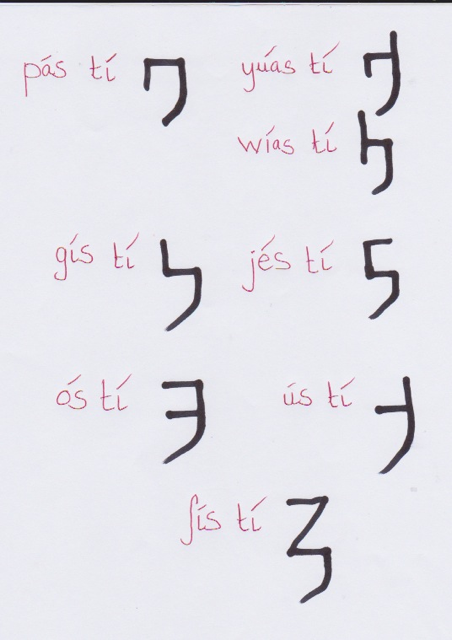

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in béu we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari.

Actually the tí does not have to follow the ergative pronoun but it usually does. There is a recognised way to write the ergative pronoun plus the reflexive particle (i.e. we have one symbol to represent two words). These are shown below.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

One other point ... béu has generally a pretty free word order. But in a sentence such as jene tí laudori (Jane washed herself) it would be pretty unusual to have the tí before jene

There is an emphatic pronouns based on the possessed form of bùa "body". The emphatic forms are given below ;-

As it is usual to drop pronouns in S or A position and just have the subject represented by the cenʔo element in the verb, if the full pronoun is given in these positions then it counts as pretty emphatic.

If a pronoun in O position should be emphasised ... ??? well in English, pronouns in this position aren't emphasised.

..... 64 Adjectives

| good | bòi* | bad | kéu |

| long | yàu | short | wái |

| high, tall | hài | low, short | ʔáu |

| right, positive | lugu | left, negative | liʒi |

| white | ái | black | àu |

| young | sài | old (of a living thing) | gáu |

| clever, smart | jini | stupid, thick | tumu |

| near | nìa | far | múa |

| new | yaipe | old, former, previous | waufo |

| big | jutu | small | tiji |

| hot | fema | cold | pona |

| open | nava | close | mapa |

| simple, easy | baga | complex, difficult, hard | kaza |

| sharp | naike | blunt | maubo |

| wet | nuco | dry | mide |

| empty | fene | full | pomo |

| fast | saco | slow | gade |

| strong | yubu | weak | wiki |

| heavy | wobua | light | yekia |

| beautiful | hauʔe | ugly | ʔaiho |

| contiguous, touching | yotia | apart, separate | wejua |

| fat | somua | thin, skinny | genia |

| bright | selia | dull, dim | golua |

| thin | pilia | thick | fulua |

| east, dawn, sunrise | cúa | west, dusk, sundown | dìa |

| tight | taitu | slack, loose | jauji |

| neat | ilia | untidy | ulua |

| soft | fuje | hard | pito |

| wide/broad | juga | narrow | tisa |

| rough | gaʔu | smooth | sahi |

| deep | gubu | shallow | siki |

| right | sèu | wrong | gói |

In the above list, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning. However in béu there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | au | |||

| f | o | |||

| b | oi | |||

| g | i | |||

| d | ia | high tone | ||

| l | =========================== | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ua | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | u | |||

| k | eu | |||

| p | e | |||

| t | ai | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

* Note that the adverb version of this word is slightly irregular. Instead of boiwe it is bowe. People often shout this when impressed with some athletic feat or sentiment voiced ... bowe bowe => well done => bravo bravo

Also instead of keuwe we have kewe. People often shout kewe kewe kewe if they are unimpressed with some athletic feat or disagree with a sentiment expressed. Equivalent to "Booo boo".

..... Adjectives and how they pervade other parts of speech

Earlier on in this chapter we discussed parts of speech. In béu, sometimes, an unmodified word can belong to 2 or 3 different parts of speech at once.

Also earlier on I introduced the gomua (G) or the infinitive, as a part of speech. This is the "base form" of the verb and it resembles a noun in many respects. It is being treated as a seperate part of speech ... just for convenience really. I do not want to get into an argument about linguistic theories etc. etc. This is just to make things easy to discuss.

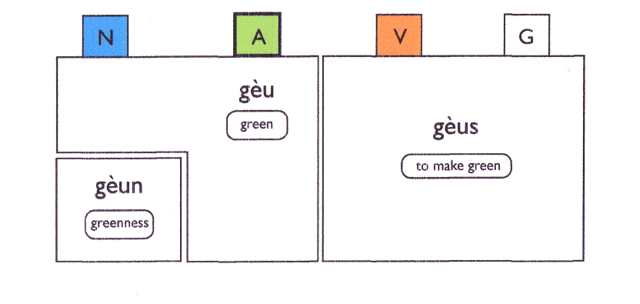

Let us start of with a single-syllable adjective. Let us see what forms a single-syllable adjective can take and what "parts of speech" these forms can belong to. Consider the word gèu "green" ;-

Along the top of the above chart you can see N, A, V and G (noun, adjective, verb and gomua).

The form under these 4 headings, shows the form gèu takes when it is one of these 4 parts of speech. gèu is fundamentally an adjective (that is what the thicker border around the "A" means).

You can see that we have two nouns forms in the above chart. One has its original form, I call this one "the substansive noun" (meaning "the green one"). The other changes its form by taking the affix -n. I call this one "the qualitative noun" (meaning "greenness").

We can see that we can derive a verb from gèu. By affixing -s we get an transitive verb meaning "to make green". You can see that the V-forms and the G-forms are the same.

Actually the V-form is not gèus. The V-form is actually a myriad of forms. But they are all built up from the gèus foundations. As an example let us build up one of the myriad of forms that the V-form can take. First we add a vowel, either a, i, o, u, e, au or ai, that represents the subject ... then we add, either r, n or s (depending on if we want the indicative mood, the subjunctive nood or the imperative) ... then we add a vowel (or consonant + vowel) as a tense/aspect marker, either ??? ... then we possibly add an evidential marker, either n, s or a. So we could get geus + i + r + i +a => geuʃiria = "you became green, I saw it" ... one of the many forms considered as a V-form.

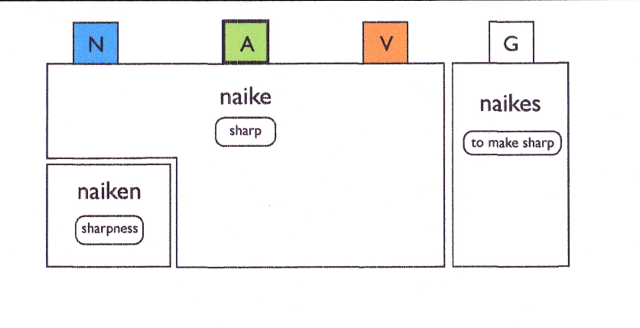

OK. We have seen how a single-syllable adjective works. Now for a 2-syllable adjective. Consider the word naike "sharp" ;-

We can see that in this case it is possible to have 3 parts of speech from only one form. However in this case the "finite" verb (V) is built up directly from naike and not from the G-form. So, for example, we have naikiria = "you sharpened (it), I saw you do it". Rather than *naikeʃiria.

Notice that all the derived verbs are transitive. There are three ways that we can make an intransitive clause.

1) pintu tí mapori = The door closed itself ... this form strongly implies that there was no human agent. Possibly the wind closed the door (or a supernatural element when it comes to that).

2) pintu bwori mapau = The door was closed ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

3) pintu lí mapa = The door became closed ... this uses the adjective form of mapa and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

By the way, the G-form of nava "open" is navai

Let us go back to gèu and consider gèu in an intransitive clause. As above we have 3 ways.

1) báu tí geusori = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved.

2) báu bwori gèus = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

3) báu lí gèu = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of gèu and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

Notice that naikes means the same as kyé sau naike (to give to be sharp) ... but why say this mouthful when you can simply say naikes.

Any single syllable adjective, must have the suffix du in all its verbal forms. For example ;-

àus = to blacken, maŋkeu = faces

ausuri maŋkiteu = they blackened their faces ... interesting construction ... we use the transitive form even tho' they perform the action on themselves.

..... Simple arithmetic

noiga = arithmetic

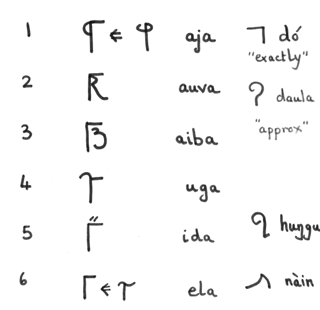

Above right you can see the numbers 1 -> 11 displayed. Notice that the forms of 1, 3, 6, 7 and 9 have been modified slightly before the "number bar" has been added.

In the bottom right you can see 7 interesting symbols. These are used to extend the range of the béu number system (remember the basic system only covers 1-> 1727). Their meanings are given in the table below.

| elephant | huŋgu |

| rhino | nàin |

| water buffalo | wúa |

| circle | omba |

| hare | yanfa |

| beetle | mulu |

| bacterium, bug | ʔiwetu |

To give you an idea of how they are used, I have given you a very big number below.

Which is => 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... E represents eleven and T represents ten ... remember the number is in base 12.

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only: if you can handle this number you can handle any number.

This monster would be pronounced aja huŋgu ufaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaifau dó

Now the 7 "placeholders" are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. Used in the same way that we would say "point"/"decimal" when reeling off a number.

When first introduced to this system, many people think that the béu culture must be untenable, however strangely enough the béu culture has lasted many thousands of year, despite the obvious confusion that must arise when they attempt to count elephants.

One further point of note ...

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say aufaidaula nàin .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say yanfa elaibau .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630" instead of "630 micro".

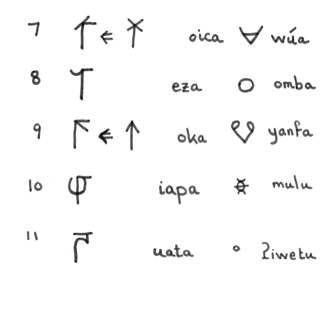

To make a number negative the "number bar" is placed on the left. See below ;-

Also a number can be made imaginary by adding a further stroke that touches the "number bar". See below ;-

As you can see above, there is no special sign for the "addition operation". The numbers are simply written one beneath the other. Similarly with subtraction but one number would be negative this time.

There is a special sign to indicate multiplication (+), and there is an equals sign (-).

Division is the same as multiplication except that one of the numbers is in "fractional form".

There is an alternative multiplication/division notation : instead of using the + sign, the two quantities can instead be written side by side (see the example above).

-6 is pronounced ela liʒi ... liʒi means left or "negative

By the way lugu means right (as in right-hand-side) or positive.

4i is pronounced uga haspia ... and what does haspia mean, well it is the name of the little squiggle that touches the number bar, for one thing.

-4i is pronounced uga haspia liʒi

-1/10 is pronounced diapa liʒi

i/4 is pronounced duga haspia

And so ends chapter 2 ...

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences