Tauro-Piscean language

Nouns

The initial letter of every noun in Tauro-Piscean is capitalised.

Like most Germanic languages, Tauro-Piscean forms left-branching noun compounds, where the first noun modifies the category given by the second. For example: Hundenhuttê (dog hut or doghouse). Unlike English, where newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written in open form with separating spaces, Piscean always uses the closed form without spaces. For example: Treënhus (tree house).

Tauro-Piscean compounds also assist in the differentiation of a compound adjective from two adjacent adjectives that each independently modify the noun. Compare the following examples:

- Essïzëren Zürênlözung - acid solution that is acetic > acetic acid solution

- Essïzëren Zürê Lözung - solution of acetic acid > acetic-acid solution

- Runden Beod Redung - discussion held at the round table > round-table discussion

- Runden Beodenredung - table discussion that is round > round table discussion (note that this does not make sense)

When forming a compound of two words, -n must be added to the end of the first word if it ends in a vowel, or -en if it ends in a consonant.

Genders

The Piscean language includes three 'logical' grammatical genders. While in many languages, the genders do not often relate to physical properties of nouns, they do in Piscean; therefore, most nouns are neuter, while creatures of the male sex are masculine and creatures of female sex are feminine. If one refers to a creature, but does not wish to distinguish sex, the neuter gender can be used as a substitute. Observe the following examples:

- tet Sunnê - the sun (no sex, so neuter)

- tet Mann - the person (no sex specified, so neuter)

- sê Mann - the man (male, so masculine)

- seo Mann - the woman (female, so feminine)

The above example shows the importance the article plays in Piscean of distinguishing between sexes in a language where one noun fits all.

Articles

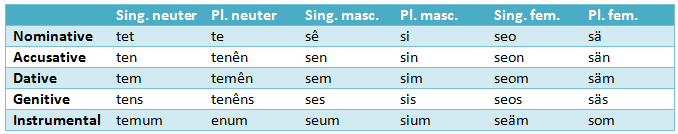

Definite articles

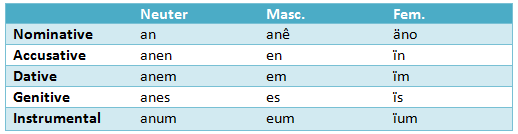

Indefinite articles

Singular and Plural

There are several ways to form plural nouns in Tauro-Piscean:

- Bok > Bokê (add –ê to nouns that end in a consonant)

- Äto > Ätos (add –s to nouns that end in a vowel other than ê)

- Sunnê > Sunnên (add –n to nouns that end in ê)

Cases

Tauro-Piscean implements five cases: nominative, accusative, dative, genitive and instrumental.

Nominative case

This case is used for the subject of the sentence (i.e. the noun doing the verb) and as a complement after: 'bean' ('to be'), 'weortan' ('to become') and 'hatan' ('to be called').

- Tet Äto be niwê - the car is new

- Tet Hund bit - the dog bites

Accusative case

This case is used for the direct object (i.e. the noun having the verb done to it/them) and after certain prepositions.

- Ikkê bïğ ten Äto - we buy the car

- Ikk et ten Banánê - I eat the banana

When there is no article with the noun, the noun itself must be inflected. To do so with a noun that ends in a consonant, add -en - or, if it is a proper noun, add -'en. If the noun or proper noun ends in a vowel, add -nen or -'nen respectively.

- Infëmaksion - information

- Ikk habb Infëmaksionen - I have information

Note that when inflecting a plural noun, it must be made plural before it is inflected for the accusative (the same applies to the dative, genitive and instrumental cases).

- Äto - car

- Ätos - cars

- Ikk mag Ätosen - I like cars

The accusative case allows for flexible sentence structure that can place emphasis on a certain word by changing its location, yet retaining original meaning. For example:

- Se Hund bit sen Mann - The dog bites the man

- Sen Mann bit se Hund - The dog bites the man

Both of the above Tauro-Piscean sentences have the same translation into English. On first glance, an English speaker might confuse the second example as 'the man bites the dog', although this is because the object comes before the subject. Because the word 'Mann' is preceded by the accusative article and 'Hund', by the nominative, those skilled in Tauro-Piscean can easily deduce the sentence's meaning. Meanwhile, the first example places emphasis on the subject, while the second places greater emphasis on the object.

Dative case

This case is used for the indirect object (i.e. the noun receiving or being given/sent/lent something) and after certain prepositions. This also translates the English word 'to' when it precedes a noun.

- Ikk jef tenen sem Lerärê - I give it to the teacher

The dative case is used when referring to travel:

- Ikk fa tem Sköl - I go to the school

To inflect a noun ending in a consonant when there is no article, add -em, or -'em for a proper noun. For a noun ending in a vowel, add -nem, or -'nem for a proper noun.

- Ikk fa Lunden'em - I go to London

Genitive case

This case is used to denote possession or ownership. 'The man's car' translates literally as 'the car of the man', but with the genitive case translating 'of' (instead of a separate word).

- Tet Äto ses Mann - the man's car (the car of the man)

To inflect a noun ending in a consonant when there is no article, add -es, or -'es for a proper noun. For a noun ending in a vowel, add -nes, or -'nes for a proper noun.

- Tet Rum Sean'es - Sean's room (the room of Sean)

- Tet Abït Gaynor'es - Gaynor's job (the job of Gaynor)

Instrumental case

The first use of the instrumental case is to replace words such as 'with' and 'by' in English in the context that they mean 'by means of' - in other words, to indicate that the noun in question is an 'instrument'.

- Tet Bän - the train

- Ikk fa bänum - I go (by) train

- Ikk fa temum bän - I go (by) the train

- Tet Kuli - the pen

- Ikk rit kulinum - I write (with a) pen

- Ikk rit temum kuli - I write (with) the pen

Despite the rule in Tauro-Piscean that all nouns begin with a capital letter, when in the instrumental case, this capital is dropped.

The second use of the instrumental case is to denote nationality.

- Englas - England

- Ikk zï englas'um - I am English (literally - 'I am by means of England')

To inflect a noun ending in a consonant when there is no article, add -um, or -'um for a proper noun. For a noun ending in a vowel, add -num, or -'num for a proper noun.

Adjectives

Adjective Endings

In English, an adjective can appear in one of two different places in a sentence:

- Separated from the noun it describes: the tree is small

- Immediately before the noun it describes: the small tree

The same phrases in Tauro-Piscean are:

- Tet Treë zï smalê - the tree is small

- Tet smalên Treë - the small tree

Notice that when the adjective appears ammediately in front of the noun it describes, it must be inflected. The endings depend on whether the adjective's final letter is a vowel or a consonant; for one whose final letter is a vowel, add -n and for one whose final letter is a consonant, add -en.

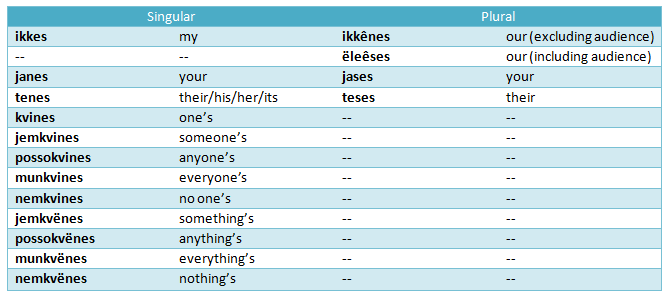

Possessive Adjectives

Possessive adjectives are translated using genitive-derived variants of pronouns. In Tauro-Piscean, they always follow the noun. Additionally, the definite article is used.

- Tet Bok ikkes - my book

- Tet Hus janes - your house

Comparative and Superlative Adjectives

Comparative adjectives

One uses these to compare things, for example when you're saying something is smaller than something else.

- smalê (small) > smalêjä (smaller)

Whereas English sometimes uses 'more' and 'less' instead of '-er', Tauro-Piscean follows regular patterns.

- intäressant - interesting

- more .../...er > ...ä (more interesting > intäressantä)

To say 'more ...', one simply adds -ä to an adjective that ends in a consonant, or -jä to an adjective that ends in a vowel.

- intäressant > intäressantä (interesting > more interesting)

To say 'less ...', one adds -ë to an adjective that ends in a consonat, or -jë to an adjective that ends in a vowel.

- intäressant > intäressantë (interesting > less interesting)

To say 'less/more interesting than ...', use 'tonnê' and the accusative case afterwards.

- An Bok zï intäressantä tonnê anen Fiêlm - a book is more interesting than a film

- An Bok zï intäressantë tonnê anen Fiêlm - a book is less interesting than a film

Superlative adjectives

Superlative adjectives are used to say something is the best, tallest, etc.

- jod (good) > jodü (best)

To say 'most ...', one adds -ü to an adjective that ends in a consonant, or -jü to an adjective that ends in a vowel.

- intäressant > intäressantü (interesting > most interesting)

To say 'least ...', one adds -uš to an adjective that ends in a consonant, or -š to an adjective that ends in a vowel.

- intäressant > intäressantuš

Comparative and superlative adjective endings

As with normal adjectives, comparatives and superlatives must have an ending if they appear directly in front of a noun they are describing.

- Tet Bok zï intäressantä - the book is more interesting

- Tet intäressantän Bok - the more interesting book

Adverbs

Adverbs describe or give more information about verbs. In Tauro-Piscean, they are the same as adjectives.

- Tet Äto be sneêl - the car is quick

- Tet Äto fa sneêl - the car goes quickly

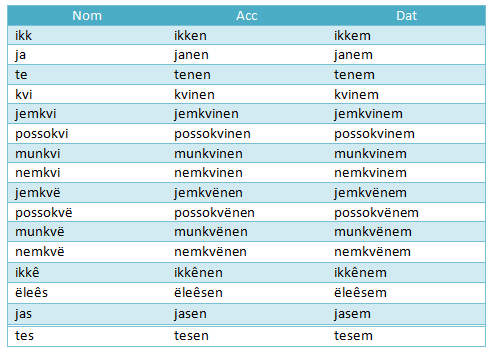

Pronouns

Direct and Indirect Object Pronouns

Like nouns, pronouns change according to the case. Here is the full ist of pronouns in the nominative, accusative and dative cases.

- Ikk mag tenen nat - I don't like them

- Te mag ikken nat - they don't like me

- Ja send ikkem anen Jefu - you send [to] me a present

- Ikk send janem anen Jefu - I send [to] you a present

Verbs

The infinitive

In their widely known form, Tauro-Piscean verbs end in -an, -ian, -rian, -wian or -jian.

This needs to be changed according to grammatical mood and tense. There is no conjugation depending on grammatical person in the Tauro-Piscean language.

The imperative

Imperative verbs express direct commands, requests and prohibitions. The imperative is formed with an infinitive verb in conjunction with a VSO (verb-subject-object) word order.

- Redan ten Bok - read the book

- Skäwian ten heonan Tramet - see this page

The indicative

The indicative mood is the most common in the Piscean language, used for factual statements and positive beliefs. It is normally formed in the present simple tense by removing the infinitive ending.

- Ikk red ten Bok - I read the book

- Ja skä ten heonan Tramet - you observe this page

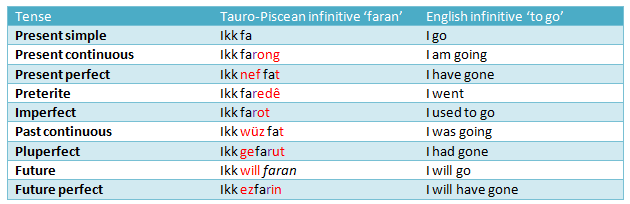

The mood is compatible with other tenses, in which cases the infinitive must be altered differently.

To form:

Present simple - if the infinitive ending is -an, -rian, -wian or -jian, remove it. If it is -ian, change it to -ê

Present continuous - remove the significant part of the infinitive ending (i.e. the -an or the -ian, but not the R, W or J that may come before those letters). Then, add -ong if the stem ends in a consonant, or -ng if it ends in a vowel.

Present perfect - the word 'nef' must be placed before the variant verb, which is formed as in present simple, but with an additional T.

Preterite - formed as in present continuous, but with -edê (after a consonant) and -dê (after a vowel) substitued for -ong and -ng respectively.

Imperfect - formed as in present continuous, but with -ot (after a consonant) and -jot (after a vowel) substituted for -ong and -ng respectively.

Past continuous - formed as in present perfect, but with the word 'wüz' in place of 'nef'.

Pluperfect - formed as in imperfect, but with -ut and -jut substituted for -ot and -jot respectively; additionally, ge- must be prefixed onto the verb if it begins with a consonant, or g- if it begins with a vowel.

Future - formed with the infinitve. The word 'will' must be placed before the verb.

Future perfect - formed as in pluperfect, but with -in and -jin substituted for -ut and -jut respectively - and ez- substituted for both ge- and g-.

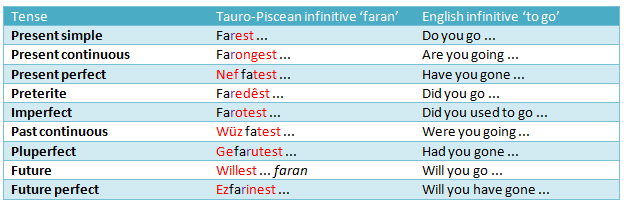

The interrogative

Verbs in inflected in this manner if they are used to ask questions. The interrogative mood not normally used with a noun or pronoun, but if context does not make this clear, a noun or pronoun can be included after the interrogative verb (VSO word order).

- Habbest anen Kuli? - do you have a pen?

In every tense, the interrogative is formed as in the indicative, save for adding -est to the verb if its final letter is a consonant, or -st if its final letter is Ê and with the future being an exception to this rule.

In the future, the word 'will' (modal verb 'willan') must be inflected by adding -est. Additionally, whichever verb is in question - in the case of the table 'faran' - is inverted to the end of the sentence.

- Willest anen Kuli habban? - will you have a pen?

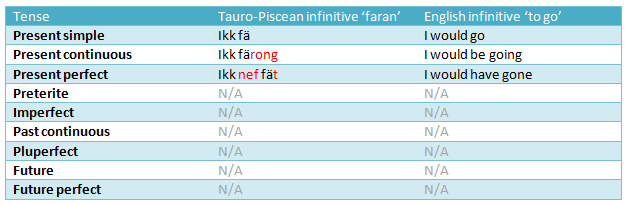

The conditional

The conditional mood is used to speak of an event whose realisation is dependent on a certain condition.

- Ikk häb anen Kuli - I would have a pen

The conditional present simple, present continuous and present perfect tenses are formed as in indicative, but with the first vowel in the verb taking an umlaut. If the stem of the verb ends in a double consonant (same letter), this must be reduced to just one. For example:

- Ikk habb (indicative) > Ikk häb (conditional)