Middlesex

The Middlesex language was the common speech register of the early Crystals, used in written communication. Men and women pronounced the words differently, and in their spoken language, they also used different vocabulary and syntax that were not written down except in quotations. Children also had their own speech register.

Scratchpad

May 18, 2021

Since there are three different kʷ sounds, at least one of them may in fact become p in at least some words, likely due to morphological conditioning rather than traditional sound change.

May 16, 2021

Feminine property suffix

Note the persistence of the suffix -ik for feminine property in an otherwise primarily CV language. This creates vowel alternations, for example turning final /-a/ into /-ek/, which in turn is pronounced [ik] by women and [ʲak] by men.

However, -e and -o probably just stay -ek & -ok. There may be some other words that restore lost final consonants.

Borrowing between registers

When men and women borrow each other's words, they convert the consonants to their own gender's forms, but not the vowels, and in some words the changes are not reversible. For example, women have just a single kʷ phoneme corresponding to men's kʷ and ṭ, and women additionally also pronounce k as kʷ before a historical /o/ vowel, because for women /o/ is /ʷa/.

Men use women's words for female property, deriving from women's own pronunciations of those words. (e.g. "my towel", etc) This leads to consonant alternations affecting the stem of the word. Likewise, all words containing an o on any tone shift it to u on that tone when referring to a man's property; this applies to both classifiers and the stems.

To some extent, the "levelled" pronunciation may win out; men pronounce both /o/ and /u/ as u, but women also have an /u/, so a woman pronouncing an /u/ can still be correct. This leads the degenerate (in the sense of levelled) pronunciations to dominate over correct and hypercorrect ones. Since men cannot pronounce an /o/, they cannot be hypercorrect and cannot restore /o/ in any way to a word that has been generalized to /u/. This does not usually apply to /e/ because women pronounce a distinction between /e/ and /i/ in most words (depending on the preceding consonant).

On the other hand, note that men can still pronounce /ʷa/, which is how women pronounce /o/, for most words (depending on the preceding consonant).

Evolution

Tapilula (0) to Star Empire Amade (1900)

It is possible that a branch of this family ends up in Kxesh; see Gold_Empire#Migration. Despite the Stars' homeland being described as Lobexon, it is likely that most migrants were from Amade.

- Accented schwas surrendered their accent to the following vowel (not the same as a stress shift, because the tone also changes).

- The "labial" vowel ə disappeared, syllabified nearby consonants or turned to i if the nearby consonants were not possible to become syllabic. Note that it never occurred after labialized consonants. Sequences such as /kəh hək/ (that is, in either original order) collapsed to form aspirated consonants, though these behaved as clusters.

- Tautosyllabic vowel sequences òi ài èi converged to ē. This did not affect syllable-straddling words like /tùya/. Likewise, èu àu òu in the same environment converged to ō.

- In some cases, the result of ài may instead be a short o, due to memories of a still-active morpheme compounding process.

- Duplicate vowel sequences àa èe ìi òo ùu shifted to long vowels ā ē ī ō ū. But the same sequences with the opposite tone pattern did not shift.

- The sequences ṁg ṅg ŋ̇g shifted to ṁb ṅd ŋ̇ġ.

- The velar fricatives g gʷ shifted to Ø w.

- The labial stops p b merged as b.

- In a closed syllable, the stops b t d shifted to w Ø Ø and lengthened the preceding vowel. New ēw āw ōw merged as ō, while new īw ūw merged as ū.

- Word-final ḳ became k. Word-final h spread across the preceding vowel; in other clusters, the /h/ transposed across the syllable boundary to form an aspirated consonant. (This is a general shift that had occurred near the beginning of the history, but it needed to happen again due to compounding.)

- The sequences bh dh shifted to p t.

- The labialized consonants tʷ dʷ nʷ shifted to kʷ v m. However the rare cluster ndʷ instead became mb.

- The labial fricative f shifted to h.

- The velar ejective ḳ shifted to g.

- Before a hiatus, the short vowels u i shifted to ʷ y, creating a new set of labialized consonants. However, the palatalized consonants were not distinct from their components.

- The sequences tʲ nʲ dʲ lʲ shifted to č ň ž y. Then kʲ ŋʲ hʲ shifted to č ň š. Palatalized labials depalatalized.

Thus the consonant inventory was

PLAIN LABIALIZED

Bilabials: p m b v pʷ mʷ bʷ w Alveolars: t n d l tʷ nʷ dʷ lʷ Palataloids: č ň š ž y Velars: k ŋ h g (Ø) kʷ ŋʷ hʷ gʷ

And the vowels were /a e i o u ā ē ī ō ū/.

Star Empire Crystal (1900) to Middlesex Baeba Crystal (3370)

- The voiceless fricatives h hʷ shifted to x h.

- The fricatives d dʷ ž shifted to r w y.

- Then the postalveolar fricative š (always from /hʲ/) shifted to s. This change operated on the surface level, meaning that, for example, men's realization of /si/ was still [si], not [sʲi] as one would expect from the pattern set by the stops.

- The consonant clusters ll nn, which occurred primarily in loanwords, shifted to ḷ ṇ.

- The labialized coronals nʷ lʷ shifted to ṇ ḷ.

- The nasals mʷ ŋʷ shifted to m̄ ŋ̄.

Both men and women had a three-vowel surface inventory of /a i u/, but because they had shifted the inherited /a e i o u/ to three vowels in different ways, none of the vowel changes were part of the shared language, and thus none were represented in the orthography. And because the consonant changes were all unconditional, the parent language spellings were all still understandable to the Crystals, and all changes in the preceding 1500 years could be attributed to spelling. Thus Crystal scholars sometimes considered their language to have been unchanged for the preceding 1900 years.[1]

Phonology

Consonant inventory

The written language consonant inventory was

Idiolectal variation

- Symmetrical variations

Women pronounced hʷ~bʷ as /hʷ/ and men pronounced it as /bʷ/. WOmen pronounced f~b as /f/ and men pronounced it as /b/. Women pronounced xʷ~gʷ as /xʷ/ and men pronounced it as /gʷ/.

- Female mergers

Women pronounced ṭ g v as /kʷ x f/.

In a few words, /s/ was hʷ before /a/ for women (thgese words had /o/ for men).

Vowels

Middlesex writing used a five-vowel script, but both men and women used a three vowel inventory, /a i u/, in their speech. The five vowel symbols were needed to tell apart which words varied by gender and which did not.

For men, the five vowel symbols a e i o u spell a ʲa ʲi u u.

For women, the five vowel symbols a e i o u spell a i ʲi ʷa u.

The /u/ may actually be /ʷu/, but this does not create a distinction between the final two vowels for men.

Adult speech registers

Men and women both substitute r for any v (which women would ordinarily pronounce as /f/) in certain words, but the pattern is unpredictable and it typically does not cover the same words. Thus, women do not often have minimal pairs where men distinguish /v/ and /f/. This is possible because the phonemes that later shifted to /r/ and /v/ had been in grammatical alternations early on. Note, though, that this is missing the final vowel.

Similarly, k can substitute for ṭ, for a similar reason, also losing the final vowel.

Women's speech

Women have a smaller consonant inventory than men, leading to minimal pairs that must be disambiguated through classifier prefixes or, less commonly, by using a different word entirely. For example, where men distinguish /nàga/ "voice" from /nàxa/ "owl", women pronounce both as /nàxa/

Men's speech

Children's speech

Children use the simple vowels /a i u/, without coarticulations. All words have consonant harmony, containing a maximum of three different consonants. They also have vowel harmony, containing a maximum of two vowels; [u] is considered a variant of /i/ and submissive to it. Nevertheless, there may still be five vowels in the spelling, as they behave in a similar manner to how adults' vowels would.

Scratchpad (Gĭri)

May 16, 2021

Children could use the prefix ŋa- for large and dangerous objects, and ŋe- as a prefix of respect for adults. (This would be pronounced with /a/ by boys and with /i/ by girls.)

If a cognate of the Trout 2P respectful pronoun /ogĭtʷo/ is found here, it could potentially lose its first three phonemes all to reanalysis, thus becoming just /tʷò/, which would appear in Middlesex as kʷò, and this in turn would be either /kʷà/ or /kʷù/ depending on gender.

Pronunciation of some sounds could filter upward into adult speech registers. Since children can only use three consonants per word, content morphemes might dominate prefixes and suffixes, and lead to harmony.

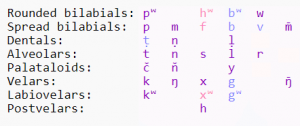

Possible consonant inventory:

Rounded bilabials: pʷ m̄ w Spread bilabials: p m b Coronals: t n l Palatals: y Velars: k ŋ g Labiovelars: kʷ ŋ̄

There were only three vowels. There may have also been a pair of voiceless fricatives /s h/, or just /h/.

These may be spelled with syllable glyphs instead, as the syllables were likely pure CV, even disallowing prenasals. Children may omit classifier prefixes when referring to their own property, using them as if they refer by default to other people's property. Thus bù "my crib, my cradle" with no prefix alongside obù "crib, cradle" which refers to any crib not belonging to the speaker.

Notes

- ↑ not 1500, because they used a different start date.