Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

..... The 5 basic word types

..

All words are derived from these 5 basic types. Actually the fengi "particle" have so many subtypes (often single particles are a subtype to themselves) that it is a bit of a fudge to say that béu has 5 basic types. Maybe more honest to say that béu has 4 groups of words and the behaviour (syntactically) of any word in these 4 groups depends on which group it is in.

..

1) fengi = particle ... this is a sort of "hold-all" category for all words (and affixes) that don't neatly fit into the other categories. Interjections, numbers, pronouns, conjunctions, determiners and certain words that would be classed as adverbs in English, are all classed as fengi.

By the way ... all affixes are counteD as a type of fengi.

An example is wò .. the preposition indicating the oblique case.

..

2) kenʒi = an object

An example is bàu ... "a man"

..

3) olus = material, stuff

An example is moze ... "water"

..

4) saidau = adjective

An example is nelau ... "dark blue"

..

5) manga = a verb ... its base form (citation form) is equivalent to the infinitive in English (or some kind of verbal noun or gerund). When used as a verb, it will take its r-form, u-form or i-form.

An example is twá ... "to meet" or "a meeting" (the concept of "meet" disassociated from any arguments, tense, aspect or whatever).

..

..

..... Kenʒi

..

kenʒi can mean "noun". It can also mean "noun phrase" (NP).

.

Probably the most "basic" of the basic 5 ... tangible and discrete.

The noun can take six types of modifiers. These six types must come in a certain order ...

..

..

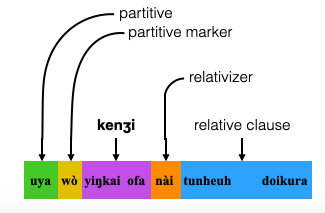

In the above diagram, an descending arrow followed by a bar indicates a closed set. A descending arrow by itself indicates an open set. Branching arrows indicate multiple possibilities.

The head of the NP can be referred to as kenʒita. Usually it is called this by lay people and by linguists when the concept is first brought up. However, thereafter it is usually referred to as húa meaning "head".

kenʒita is kenʒi plus the diminutive suffix. kenʒi can also take the augmentative suffix -uma. kenzuma "extended noun phrase" is a normal kenʒi, with either a relative clause (RC) appended to the right or a partitive appended to the left hand side

The words highlighted in red convert the noun phrase (or indeed the sentence in which the NP is embedded) into a question. A blue circle indicates the only mandatory element. But even these elements can be dropped on occasion ... when they are understood from context or the preceding conversation. When we have one adjective, and the head is understood, ɘ can be substituted for the head, kɘ if the head is plural.

ɘ gèu = a/the green one : kɘ gèu = a/the green ones

These two particles can also be used with other noun modifiers, however not always mandators with non-adjective modifiers.

ɘ nái = which one : kɘ nái = which ones

kɘ dí = these ones : ɘ dè = this one

However nái, dí and dè can constitute NP's by themselves. A bit like English

Looking at the chart above might give you a false impression of béu noun phrases. The number of modifiers within a noun phrase is usually only one or two. When there is two, they must occur in a certain order, hence the necessity of the chart above. I don't think it would be easy to process a noun phrase with six modifiers, probably some of them would be shunted off into a RC with an initial copula. A noun phrase can take multiple RC's. They can stand beside each other in a sort of apposition.

I should make one further point here. The particles ú "all" and jù "no" can appear to the left of the head. They can also appear in the quantity slot.

..

... Quality

..

More than one adjective is allowed in this slot. For example ... bàu gèu tiji = the little green man

kái meaning "what type" can also appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu kái = what kind of green man ? ... (NP question)

há bàu gèu kái glà timpori = what kind of green man hit the woman ? ... (sentence question)

Now when you have multiple adjectives they will have a certain order depending upon their sub-category.

This is the same as English ... for example, you always say "the third big black dog" and never "the black third big dog".

béu uses the exact same order as in English but the other way around.

béu has two adjectives that come in this slot that are worth mentioning. They might have claims to particle-hood, but I guess their appearance in this slot marks them as particles. Perhaps they are both feŋgi and saidau.

..

... "other"

..

dòn = "other"

The semantics of this word remind me of the semantics of tuge/jige. With the relative quantifiers the speech participants have agreed on the number/amount relevant to the situation. tuge/jige are used to change this value. Similarly dòn is used in a situation where the speech participants have agreed on the population (of whatever noun category) under consideration but one of them wants to expand this population.

There is a theory that this word is related to "pilamo" 6, possibly modified by pilamo 15. But who can say for sure.

By the way ... dòn dòn = etcetera

..

... "laubo"

..

laubo = enough

..

... Quantity

..

This slot is very interesting ...

The above chart is split into definite and vague sections. All the items under definite represent an integer (or "the empty set" or "the full set"). The items under vague represent an approximate number/amount. This section is further divided into discrete and non-discrete (i.e. countable.non-countable).

yè modifies both discrete and non-discrete. It means a moderate amount ... some value between zero and "all". It does NOT mean "indefinite" ... "some man" is bàu èn, not *bàu yè.

This word can be used to mark plurality (together with iyo and hài) for those nouns that can not be pluralized in themselves. For example ... húa, "head" : húa yè, "heads".

jí jí and jía are about equally common and mean the same thing. However jía tends to be used in more formal situations and jí jí in less formal.

..

IMPORTANT RULE ... "If you have ANY word in this slot, the head of the NP must be in its singular form."

[ yúr moltai.a laubo "they have enough doctors" .... maybe it can be argued that semantically laubo makes doctors plural here. But laubo is an adjective however, so moltai.a must be used instead of moltai ]

..

láu (how many) can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the NP (and hence the clause containing the NP) into a question. For example ...

bàu jutu láu = "How many men are big ?" or "How many big men ?" ???????????

..

The chart above shows only the terms used for absolute quantity ????????????????? It does not cover, what I call relative quantity. Let me explain ...

Imagine the speaker and the hearer both have an idea of the number/amount relevant to a situation but one of them wants to change this number/amount. The amount he wants to change this agreed number/amount by, I call the relative quantity. It can be positive or negative. When positive we use the word tuge "more" ... when negative we use the word jige "less" *. For example ...

turi waulo tuge = more dogs came

| t-u-r-i | waudo | tuge |

|---|---|---|

| come-3PL-IND-PST | dog | more |

These to particles can be modified by some (most) of the terms given in the chart above. They can be modified by any of the terms hi-lighted in orange.

For example ... bía tuge ima = two more beers please"

..

* These words might be derived somehow from jutu "big" and tiji "small" ... along with the comparative suffix -ge **.

The comparative suffix can be appended to any adjectives. For example ... jini "clever" => jinige "cleverer" : hau?e "beautiful" => hau?ege "more beautiful"

There is also a superlative suffix ... -mo. So jinimo "cleverest" amd hau?emo "most beautiful"

** There is an independant word gé which might be related to the comparative suffix. It is a particle that always comes in twos. For example ... gé tundu ... gé bói "the more the merrier".

Sometimes you coma across bù tuge "no more". This should be analysed as a contraction of bù ?ár tuge "I don't want more".

*** Perhaps wóin is related to the verb gwói "to pass by" plus the past participle -in.

..

... Ownership

..

Basically you can just stick a personal name, a pronoun or any NP in here and the head noun will be considered owned by the object inserted here.

Sometimes, the particle yó precedes the object inserted.

For example jwado gèu yó jene = Jane's big green bird

Note that the particle yó is usually dropped when the possessor is next to the head. However as other elements intervene, the likelihood that yó is used increases.

If mín (who) is stuck in this slot ... then we have a question. For example ...

jwado gèu yó mín = Whose big green bird ? = Whose's the big green bird ?

There can be ambiguity with some kenʒi possessing a genitive. For example ...

Does waudo bàu dí mean "the dog of this man" or "this dog of the man" ?

To get around this, we have a special rule ...

"If anything is in the ownership slot, dí and dè never appear in the determiner slot. Instead they appear as dían "here" and dene "there" in the locative slot"

Note ... sometimes ownership as such is not what is of interest, it is if a person has actual physical possession. In this case yó is not used. But the object takes pilamo 2.

jwado gèu là Long John Silver catora = The big green bird (on Long John's shoulder presumably) is chatting away.

Actually segments showing actually physical possession like the example above, go in the locative slot which we will cover next.

..

... Location

..

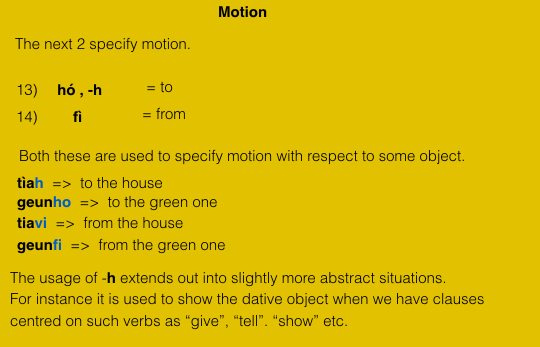

Ordinal numbers appear in this slot. The ordinal numbers are ...

You will notice that there are two words for first ... da?a and dahua. They are both equally common, but da?a tends to occur in the presence of dima or duya while dahua tends to occur in the presence of dauci.

..

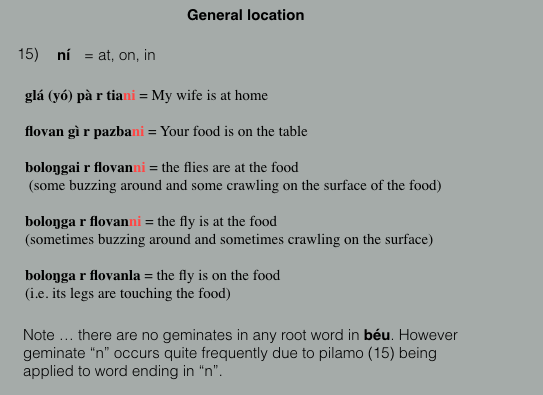

Proper locatives comprise a noun plus one of the 9 pilamoi .... pi la mau goi ce do bene komo ni. For example ...

duzu pobomau = The oryx on the mountain

Also pilamo 14 turns up in this slot. These items are strictly not giving information about "location" but rather "origin". They are classed as a locatives nevertheless. For example ...

bàu glazgofi = a/the man from Glasgow

If the location consists of more than one word, the usual rule applies and the pilamo appears as a preposition ...

duzu máu pobo jutu = The oryx on the big mountain

There is a tendance that the longer the locative item, the more likely the locative item will be shunted into a relative clause ...

duzu nài r máu pobo hau?e jutu = The oryx on the big beautiful mountain

nài r máu pobo hau?e jutu is a relative clause. We will cover RC's in a bit.

All prepositions that are not pilamo lead to the location being shunted into a relative clause. For example ...

polgamo nài r bain gwai.a = "the sailing boat which is among the islands" or simply "the sailing boat among the islands"

..

Also dá "where" can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the noun phrase into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu dá = where is the green man ?

..

* Probably derived from uci "tail".

..

... Determiner

..

There are five of these ... dí (this), dè (that), nái (which), èn (some) and ín (any) . For example ...

dí and dè are called demonstratives in the WLT. They will be covered in the section after next.

nái turns the whole noun phrase into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu tiji nái = which little green man ? ... noun phrase question

And of course, if a NP represents a question, any clause containing this NP will also be a question. For example ...

bàu gèu tiji nái glà timpori = which little green man hit the woman ? ... a clause AND a question

èn "some" appear in this slot ... bàu gèu tiji èn = "some little green man" ...... indefinite

ín "any" appear in this slot ... bàu gèu tiji ín = "any little green man" .............. super indefinite

There is one little rule to remember ...

"Only one item is allowed in this slot, so if you want an indefinite as well as a demonstrative, the demonstrative is shunted off to the locative slot and given the form dían or dene."

I guess this is logical in a way. dí and dè were originally associated with pointing. But when the object is indefinite, how can you point ? "here" or "there" is about as definite as you can get.

..

... Side-note re demonstratives

..

dí "this" and dè "that" are two words that orientate and focus the hearer's attention on an object (or location *) in the speech situation. These words are called demonstratives in the WLT.

According to Holger [ Diessel (1999:57) ] ...

i) A demonstrative can be construed as an argument in its own right. That is, it can constitute a NP without any additional elements.

ii) A demonstrative can co-occur with a noun in a NP. That is, it can be a noun modifier.

iii)* A demonstatives can function as a verb modifier. It specifies (the) location (where something happens **).

* Perhaps in a more earlier version of the WLT "location" and (iii) would not be included in the definition of determiner. English and béu conform to this earlier version of the WLT. However I think it is a good idea when considering all the world's languages, to use this wider definition of "demonstrative".

"**" Perhaps in a language where a copula is not routinely used "where something happens" would not necessarily be appropriate.

And here are examples of the above three functions (in English) ...

a) This is excellent.

b) That guy is an idiot.

c) Here we do things differently.

Diachronically, these three functions can run into each other. Function (a) and function (b) are particularly close. They have the exact same form in English, but no confusion can occur, because "this/that:b" can be deduced to be inside a NP by the rules of English grammar. Most languages in the world (70%) have identical forms for "this/that:a" and "this/that:b". Of the languages that do not have identical forms, the difference can be quite subtle. For example in Thai นี่ [ nii falling tone ] is "this:a" and นี้ [ nii high tone ] is "this:b". ........... [see WALS 42A]

Some languages lack (a). For example, in Korean, to express "this:a" you must say "ce il" meaning "this thing". So (b) used instead of (a)

Some languages lack (b). They would say something like "the guy here" instead of "this guy". So (c) instead of (b)

Some languages lack (c). They would say something like "this place we do things differently" instead of "here we do things differently". So (b) instead of (c.)

[ And while we are talking on this area, perhaps we should mention 3rd person pronouns (see WALS 43A). Some languages lack 3rd person pronouns. They cover this function by saying something like "this" or "that guy" ... A further point of interest (well, I find it interesting anyway) is that the English he and here are cognates. Going back to a P.I.E. form meaning (a) or (b). -r was a ProtoGermanic adverbial suffix. ]

béu patterns pretty much like English (and the pattern of English is not atypical of the world's languages) ...

dí = "this:a" : dè = "that:a"

dí = "this:b" : dè = "that:b"

dían = "this:c" (i.e. "here") : dene = "that.c" (i.e. "there")

I was originally thinking of just appending the béu adverbial suffix -is to produce (c). But rejected that idea in order to get more phonological contrast between ...

(A) "this:c" and "that.c", (B) "this/that:a/b" and "this/that:c"

With dían there is a hint that it might be derived from dí plus pilamo 15. And also with dene ... a hint that it might have the same origin. But who can tell. These things are lost in the mists of time.

..

... Further uses of dí and dè

..

If we first hear a plural noun articulated in a conversation, the most likely meaning we would assigned to it would be the universal set. For example moltai.a. There is a more explicit means to express the universal set. For example ... kài moltai = "doctor.kind" but this construction is seldom used.

An example of usage is ... moltai.a súr jini = "doctors are clever"

OK ... now lets zoom in a bit. To zoom in we need to take in or give out some narrative. So now we hear the following ....

Next week British junior doctors will withhold many services in protest against the long hour expected of them

OK ... after hearing that ... moltai.a dè would be taken to mean "British junior doctors"

OK ... lets hear a further bit of narrative ...

Much to the disgruntlement of the senior doctors who will have a hard week ahead of them making up for the short fall.

OK ... after hearing that ... moltai.a dè would be taken to mean "British senior doctors". So, what dè refers to doesn't persist long, Our perspective is continually changing.

[ I can't help thinking that the proximate/obviate system existing in Plains Cree would be very useful. You could keep track of two protagonists through a discourse without reverting to full NPs. But I guess there are cognative reasons why it is difficult to use. Well, if it was easy to use, it would be far more wide-spread. It must be very useful. ]

This is in normal discourse. However if some objects are physically pointed out * when first introduced (and presumably they stay in sight for the duration of the discourse) what dí and dè referred to would persist.

So we can see that dè points back in time. It brings to the top of consciousness, the last set of doctors talked about.

..

In a narrative many objects are encountered. If a newly introduced object is marked by dí it means that the object is important to the narrative and you will shortly be getting more information about it. The process is not exactly the inverse of anaphora. But one is compatible with "information given in the past leading to easy identification of which object in particular we are talking about. The other is compatible with "in the near future I will give you information about this object and you will be able to identify which object in particular I am talking about as well as I can"

béu and English are exactly the same in this respect.

* Not necessarily by using a finger ... a gesture with the head ... or even the orientation of the eyes can suffice.

..

... Kenzuma

..

béu also has what I call an extended noun phrase. An extended noun phrase is a normal NP with either a partitive appended to the LHS, or a RC appended to the RHS.

The example below shows an extended noun phrase kenzuma with both a partitive AND an RC ...

| uya | wò | yiŋkai | ofa | nài | tunheu-h | doik-u-r-a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ..... | three | P12* | girl | five | REL | townhall-DAT | walk-3PL-IND-PRES |

..... Three of the five girls that are walking to the townhall.

..

Now remember ... by the rule given in QUANTITY section ...

moltai eja "four doctors" .......... "doctor" takes no plural marking ...

But if plurality is marked outwith the kenʒi but in the kenzuma, the head take its plural markings. Two examples ...

eja wò moltai.a "four of the doctors" ............................................ "doctor" is marked as plural even though eja gives plurality to the phrase.

moltai.a nài solbura bía "the doctors that are drinking beer" ....... "doctor" is marked as plural even though the -u- in solbura indicates plurality.

..

* the twelfth pilamo

..

... The relative clause

..

The béu relative clause is pretty similar to the English relative clause. However not exactly so.

A relative clause is a clause that modifies a NP of course. I think the best way to explain how the béu RC works is to give three examples. Each example will demonstrate a subtype of RC. In each example I will reconstitute the plain clause (PC) underlying the RC by looking at the NP and the RC.

(1)

| yiŋkai | ofa | nài | doik-u-r-a |

|---|---|---|---|

| the girl | five | REL | walk-3PL-IND-PRES |

=> the five girls who are walking

NP = yiŋkai ofa : RC = nài doikura => PC = yiŋkai ofa doikura "five girls are walking" ....... notice that nài is binned.

In the above PC yiŋkai is absolutive.

(2)

| bàu | nài-h | glá-s | fy-o-r-i | yiŋkai-wo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| the man | REL-DAT | women-ERG | tell-3SG-IND-PAST | girl-ABOUT |

=> the man to whom the woman told about the girl

NP = bàu : RC = nàih glás fyori yiŋkaiwo => PC = bàuh glás fyori yiŋkaiwo ............ notice that nài is again binned. Also -h has to find some other word to stick on to.

In the above PC bàu is dative.

(3)

| gwai.a | nài | polg-ai-r-a | ala | ʃì |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| the islands | REL | sail-1PL.INC-IND-PRES | between | them |

=> "the islands that we are sailing between"

NP = gwaia : RC = nài polgaira ala ʃì => PC = polgaira ala gwaia ...................... nài is again binned. Also ʃì is discarded. The NP must be positioned behind ala, the preposition that governs it.

In the above PC gwaia is not absolutive, also not adorned by a pilamo. Instead it exists in a prepositional phrase. For this reason, a pronoun ʃì is needed in the RC to represent the NP

..

I believe that Arabic structures its RC in a similar way to the above.

..

OK ... you should all be experts in RC's now. You just run backward the 3 NP + RC => PC processes.

..

This is discussed in greater detail in CH5.

..

... The partitive

..

A few sections back I mentioned dòn ... the béu equivalent to "other/others/the other/another/the others".

dòn is used where the speech participants have agreed on the population (of whatever noun category) under consideration but one of them wants to expand this population.

This expansion is a bit like "a shot in the dark", the speech participant requesting additional items usually is in the dark as to that additional items are available. Because of this, there is only one word dòn. I mean, if the speech participant requesting additional items had an idea about what additional items were available, he could add more detail along with his request. Perhaps we would have donu meaning "another with a bell", doni meaning "another with a whistle" ... well O.K. I am being a bit facetious ... but you understand what I am getting at.

Now dòn is used to expand the population under consideration ... to increase the scope of the conversation ... to sort of "zoom out".

Now sometimes it is necessary to "zoom in". For instance suppose you heard "three of the doctors decided to stop off at the pub on the way home" within larger narrative. After this point, these three doctors could be referred to as they. The main-protagonists/subject/topic have been reduced from eight to three. Zooming in is not a shot in the dark. The population under consideration is a known concept. The usual method is to specify the "new scope" plus the "original scope" in some sort of construction. The languages of the world all have methods for zooming in ... usually some quite simple construction, often involving a particle which has evolved from "from"/"out of". wì is the particle used in béu. Some examples of its use ...

ú wì moltai.a = all of the doctors

yè wì moltai.a = some of the doctore = several of those doctors = a number of those doctors

jù wì moltai.a = none of the doctors

tontu wì moltai.a dí = the majority of these doctors

a?a lú tuge wì moltai.a dè more = one or more of those doctors

hài wì moltai.a dè = many of those doctors

ima ín wì moltai.a dè = any two of those doctors

moltai.a wì bawa dí = the doctors out of these men

..

I suppose the nearest equivalent of wì is "of". However wì has not so many functions as "of". For "belonging to", yó is used. For "relating to"/"connected with". wò is used.

[Still thinking if wì should be involved with "a glass of milk"/"a heart of gold"]

..

THE BELOW SHOULD GO TO A SECTION ABOUT QUESTIONS

With a more complex NP it is usual to break it up in order to specify exactly which element is being questioned. For example ...

bawa gèu tiji láu pobomau nài doikura = " How many little green men on the mountain that are walking? "

bawa gèu tiji láu nài doikura _ láu r pobomau

wò bàu gèu pobomau nài doikura _ láu r tiji

wò bawa gèu tiji pobomau _ láu doikura = w.r.t. the little green men on top of the mountain, how many are walking ? ... or ...

wò bàu tiji pobomau nài doikura _ láu r gèu = w.r.t. the little men on top of the mountain who are walking, how many are green ?

THE ABOVE SHOULD GO TO A SECTION ABOUT QUESTIONS

** You don't know which two ... bit we are defining them now ... henceforth we shall refer to them as nù

..

Note ... ʔà moltai dí means pretty much the same as èn moltai dí ... one a selective, one a numerative.

In béu, èn is preferred over ʔà to code indefinite [ ??? go into indefiniteness after this section ??? ]

ʔà moltai dí could mean "the one man here" but ʔà/"one" is superfluous in both béu and English (unless you were to appand a relative clause)

..

The distributive can occur in the tail of an extended NP. For example ...

ò ò wÌ moltai.a dí ... = You see the doctors here ... well everyone of them ...

[ Of course if "the doctors here" was on the top of every ones mind ... then only ò ò would be expressed ]

OK ... I have explain all the above using the determiner dí. But it is exactly the same pattern with a different determiner or no determiner at all.

I have explain all the above using a multi-syllable head. But the same pattern holds for mono-syllable heads ... regular and irregular. For example you could change wèu "vehicle" or "car" for moltai and nò wèu for moltai.a in the above explanation and everything would hold. Or bàu for moltai and bawa for moltai.a.

Also pronouns follow the above pattern. But note ... "those two*" in English is hói nù "two us" in béu ... "you three" is léu jè ... "us four" (including you) is ega magi ... "us five" (excluding you) is oda manu ... and so on.

"five of them" being nù làu oda of couse, following the exact same pattern that a normal noun takes for partitiveness.

á hói manu doikuarua í london = "the two of us will walk to london" OR "us two will walk to london" ... [ I guess there would be a tendency to drop manu??? ]

á manu làu hói doikuarua í london = two of us will walk to london ... [tendency to drop manu??? ]

* I guess English is a bit irregular with the 3rd person plural pronoun. This would be "they two" if it patterned the same as the other pronouns.

WHAT ABOUT .... enough of the men .... too many of the men ... above 100 of the men ... more of the men

all others => ú lòs

some others => nò lòs

any doctor => ín moltai

any doctor here = any of these doctors => ín moltai dí

any of the doctors here => ín moltai.a dí

..

ʔà ʃì = it ... nò ʃì = them (inanimate)

..

| 1 | ʔà ʃì nái | which one |

| 2 | nò ʃì nái | which ones |

| 3 | léu ʃì nái | which two |

| 4 | léus nái | which two |

..

*I don't want to get sidetracked as to why this is so ... not at the moment.

**In natural languages the partitive marker usually means (or meant at one time) something like "of" or "from" or "out of". béu is not a natlang. I like wò.

***Two other numeratives that we haven't mentioned yet are tontu "the majority"/"most" and tonji "the minority".

ton = bit/part/section ... tontu <= ton jutu ... tonji <= ton tiji ... toŋko = to seperate ???

..

..... Olus

..

This category is for uncountable things such as "water" moze.

olus also combines with other elements to form "OP" (olus phrase.

By the way ... "SP" (senko phrase), "OP" (olus phrase) and "MP" (manga phrase) are all types of NP.

There are two differences between an OP and a SP.

1) Nothing in the numerative slot

2) Usually a "partitive measure phrase" added as an additional slot.

..

hói honkoi "two cups" ... is a typical "measure phrase" and làu is the "partitive particle".

So ... an example of a NP with olus as head ...

?azwo pona làu hói honko "two cups of warm milk"

Two extra adjectives are admitted into the adjective slot ... hè "a lot of" and iyo "a little" (Yes ... iyo was formerly in the numerative slot meaning "few")

..

A few hundred words have a dual existence ... in one guise olus in another guise senko. With final vowel can be e u a o or i (the last one is especially common) they have a collective meaning. For example ...

| bodi | ng-o-r |

|---|---|

| birds | fly-3SG-IND |

=>small birds fly ................. [notice the third person singular agreement on the verb]

However with a change of the final vowel to ai these concepts become countable.

| bodai | lail-o-r-a |

|---|---|

| a small bird | sing-3SG-IND-PRES |

=> a small bird is singing

Which can be made plural by putting a number in front (or one of the other numeratives).

| léu | bodai | lail-u-r-a |

|---|---|---|

| three | small bird | sing-3PL-IND-PRES |

=> three small birds are singing

Note .... the singular of some nouns also end in -ai. For example moltai "doctor". These words take a plural by adding an a ... moltai.a "doctors". However the nouns ending in -ai that have a collective equivalent, never mark plurality on the actual word. So "little birds" is nò bodai rather than *bodai.a.

..

| yinki | crumpet | yinkai | a young unmarried woman, an attractive girl, a virgin |

| toti | children | totai | a child |

| wazbo | distance | wazbai | 3,680 m (the unit of distance ... the béu km or mile) |

| malkufa | cabbages | malkufai | a cabbage |

..

Words derived using the prefixes mi/mai also pattern with these dual identity words. For example ... beumai = "somebody who believes in béu : beumi = "the entire body of people who believes in béu.

..

Remember that all collectives take singular pronouns and, if they are A or S arguments, produce an -o- in slot 1 of the verb (as opposed to -u-).

..

There is a particle kài, that when put in front of a saidau or a senko makes an OP (olus phrase). You hear it a lot prefixed to animal names ... like when talking about characteristics which are common to an entire species. For example ...

sadu "elephant" ... kài sadu "the elephants" or "elephants" ... as in kài sadu r jodo jini "the elephant is an inteligent animal"

gèu "green" .......... kài gèu "the green ones"

| kài sadu | r | jodo | jini |

|---|---|---|---|

| elephant-kind | COP | animal | clever |

Note ... kài is in free variation with k+

** Birds smaller than pidgeons are bodi. Birds that are pidgeon size and above are jwadoi (the singular being jwado).

..

..... Saidau

..

The saidau (adjective) has two uses in béu. It can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu gèu = a/the green man

bàu r gèu = a/the man is green

gèu above is a simple adjective. Adjective phrases exist as well.

An important particle that increases the degree of an adjective is sowe. For example ... gèu sowe "very green"

..

These adjectives can become nouns by froning them with ə, kə and kuwai.

ə gèu = a/the green one

kə gèu = a/the green ones

kuwai gèu = greenness

[ NOTE : I don't think the schwa is visually distinct enough. From now on I will use a plus sign to depict the schwa ]

+ gèu = a/the green one

k+ gèu = a/the green ones

kuwai gèu = greenness

OK ... that's better.

+ and k+ are historically derived from ?à "one" and kài "type". Actually they are in free variation with their historical counterparts ... a bit like "either" in English can have two pronounciations. When you want to emphasize, you would of course use the phonetically heavier version.

kuwai is a word meaning property/characteristic.

Actually these 3 words are also productive with "locatives" and "genitives" as well. For example ...

+ pobomau = the one on top of the mountain

+ yó jene = the one belonging to Jane

..

..

The above chart shows the main derivational pathways in béu. Only pathways 2, 3, 4 are relevent to this section.

..

Note ... + gèu sowe = "a/the very green one" ... sowe never modifies a senko.

By the way ... determiners and relative clauses can also stand by themselves, but they are unmodified when they do so. (Note to self : are you sure about this ?)

..

..... Specifying the roll of a noun

..

In total there are 17 cases plus the unmarked case (the absolutive case). The absolutive is not called a case in the béu linguistic tradition : instead it is called "noun base"

These 17 cases are called the pilamoi.

These are attached to a noun and show the relationship of that noun with respect to the rest of the sentence.

..

The word pilamo is built up from ;-

pila (v) = to place, to position, to correctly align

pilamo (n) = the positioner

..

Probably the most important case is the ergative (the 11th case). In English it is the order of the verb and the arguments that shows who is the doer and what is the "done to". Namely the A and S argument come before the verb and the O argument after ... [ English is a non-ergative language and hence the A and S argument get treated in the same way.]

In béu, to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", the suffix -s is appended to the A argument. For example ...

..

glás bàu timporyə => The woman has hit the man ..... (with "the man" being the O argument)

glá bàus timporyə => The man has hit the woman ...... (with "the man" being the A argument)

bàu doikora => The man is walking ........................... (with "the man" being the S argument) ... [ béu is an ergative language and hence the O and S argument have the same form.]

..

..

There is a regular relationship between preposition and affix, apart from (11) which is highly irregular, (16) which is irregular and (17) which is very slightly irregular. When suffixes they all are usually written using a single consonant. No confusion can arise as normally consonants are illicit word finally. However there is no abbreviated forms for (15) and (17). Of the 17 consonants, ? and n are not involved in these abbreviations.

..

The pilamoi are either realized as either affixes or as prepositions.

Whether the pilamoi appears as an suffix or a preposition depends on whether you have a N (noun) or a NP (noun phrase). If you have N the affix is used, if you have NP the preposition is used.

tiadua = beyond the house

dùa tìa yó yinkai hauʔe = beyond the house of the pretty girl

..

Note on the script ... If they are realized as affixes then, in the béu script uses a sort of shorthand. That is the affix is represented as one letter.

..

Earlier we have seen that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilamo affixed to them. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilamo then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

jonos jenes solbur moze = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of an affixed pilamo, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lé should be placed between them. For example ...

jono lé jene maumur = "John and Jane sleep"

Compare the above two examples to jono jene maumor = "Jane's John sleeps" ... that is "the John that is in a relationship with Jane, sleeps".

..

.. As parts of speech

..

pilamoi of location phrases (i.e. nouns with 1 -> 8 or 15) can be considered adjectives. They must come after a noun or a verb.

pilamoi of motional phrases (i.e. nouns with 13, 14, 16 or 17) can be considered adverbs. They can come in any position because it is understood that they are qualifying the verb.

pilamo phrases defining sentence rolls (i.e. nouns with 9, 10, 11 or 12) can come anywhere. They are considered clause arguments.

(Note to self : move the below to a different section)

* [ Notice that in English, you can either say ... "a bird is in the tree" or "in the tree is a bird"

In béu only jwado r ʔupaiʔe is valid ... also note that in this case jwado is not definite because it is left of the verb. That rule doesn't work with the copula. ]

jenes solbori moʒi lé ʔazwo = "Jane drank water and milk"

jonos jenes mwuri hói sadu lé léu ʔusfa = John and Jane saw two elephants and three giraffes.

This word is that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

..

..... Manga

..

These are verbal nouns or infinitives.

English is very chaotic as to the various means it derive nouns from verbs. For example ... "discover" + "y" => the discovery ... "destroy" + "tion" => the destruction ... "run" + ∅ => the run. béu is as orderly as it is possible to get ... the verbal noun is in fact the base form of the verb.

[ Note to self : I need to do a lot of translation excercises to get my head around hulka = destruction = to destroy = destroying ]

In this section I will usually translate a manga into its infinitive equivalent in English. For example ...

solbe => "to drink"

Now the manga can amalgamate with other elements. For example ...

solbe saco = "to drink quickly" or "drinking quickly"

...and adding more elements ...

solbe moze sacois = "to drink the water quickly" or "drinking the water quickly"

The S or O argument in an active clause ... in the corresponding MP, must immediately follows the manga. Also because saco no longer immediately follows the manga, it must be explicitly tagged as an adverb by the -is suffix.

... and adding even more elements ...

solbe moze sacois hí jono = "John drinking the water quickly" or "for John to drink the water quickly".

The A argument in an active clause, ... in the corresponding MP ... comes last and has the particle hí in front of it. (the particle hí is probably related to the egative particle há)

Note ... other clausal elements ( dative object, time, adverb, instrument, reason, purpose) can be added ... in our example they would come between sacois and hí.

Now all elements from the active clause, that make it into a MP ... I refer to as "the manga heart".

..

This manga heart can in turn amalgamate with other elements. These elements are pretty much the same ones that you find in a SP. The important thing is that the head has been replaced with a heart (my terminology). As you can see the heart has its own structure (as seen in the red box, below) ...

As you can see above, the manga heart can take a slightly different form. The adverb can be put immediately after the manga. In that position it looses the -is suffix.

The total amagamation ... I call a MP "manga phrase". (As opposed to a SP "senko phrase" or a OP "olus phrase" ... all 3 being sub-types of noun phrase "NP")

You can see that a MP is pretty much the same as a SP, but with the senko (the head) replaced with a manga heart.

..

In the example we are using sacois "quickly" can be taken out of the heart, and placed in the senko phrase as saco. In the adjective slot of course.

Also you have a choice as to where you can place any locative. A locative can be placed in the locative slot of the senko phrase, or they can be placed in the heart, just before hí. For example ...

solbe moze sacois tiapi hí jono = solbe moze sacois hí jono tiapi = "John drinking the water quickly in the house" = "for John to drink the water quickly in the house".

..

Now we have already introduced the pilamo. Theoretically all pilamo can be appended to a MP ... but most such constructions don't make much sense ... however -tú appends often. For example ...

tore doikatu = "he/she came on foot" or "he/she came by walking"

tore doikatu = "he/she came on foot" or "he/she came by walking"

tore tú doika saco = "he/she came by walking quickly"

This "tú-construction" acts as an adverb. Notice that the particle tú acts as it normally does and appends to the end of a single word, but stands alone to the left of a multi-word phrase.

..

Also là appears often in conjunction with manga

The là-constuction acts as an adjective. An adjective meaning "XXX-ing" at the (relevant ???) moment of speech". As with all adjectives it can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu doikala = a/the walking man

bàu r doikala = a/the man is walking .... [Note ... bàu r doikala means exactly the same as bàu doikora]

là differs from most other pilamo in that, with a manga, it never stands alone. For example ...

bàu doikala sacois = a/the quickly walking man .... [Note ... the affix -is is appended to saco to show it is connected to doika and not bàu] instead of *bàu là doika saco

In a là-constuction, everything has the same order as a MP ... the only difference is that -la is appended to the manga and hí XXX is dropped. Well hí XXX represents the A argument and the A argument is the thing being described by the là-constuction, so no need to exist inside the construction.

This là-constuction can be called the present participle. The present participle has the meaning "in the process of XXXing".For example ...

doika "to walk" => doikala "in the process of walking"

kata "to cut" => katala "in the process of cutting".

When derived from a transitive verb the object can be included as well. For example katala lazde "in the process of cutting the grass".

[ Note ... bàu katala lazde "the man cutting the grass" means the same as bàu nàis katora lazde "the man who is cutting the grass" ... however the first is nearly always preferred ... well it is shorter ]

[ Also note ... pà r katala lazde means the same as (pás) katara lazde ... however the second is nearly always preferred ... well it is shorter ]

O arguments (in an equivalent active clause) can be modified by the là-construction as well. For example ... lazde jwola kata "grass being cut" ... jwola kata being classed as an adjective phrase (jwòi meaning "to undergo").

..

Also pí appears often in conjunction with manga

The pí-constuction acts as an adverb. An adverb meaning "the r-form (matrix verb) happened during the time of the action qualified by pí.

jonos lailore doikapi = "John sang while walking earlier today"

jonos lailore pí doika tunheun = "John sang while walking to the civic centre earlier today"

..

manga ... as well as appearing as arguments in a clause. That is S, A, O, CS and CO, also appear as complements to auxiliary verbs.

One such auxilliary is tuma meaning "to squeaze" or "to force". [ when it means "to squeaze" it is followed by a senko and is acting as a normal verb, when it means "to force" it is followed by a manga and is acting as an auxiliaryl verb ]

tomos tumori doika jene = Thomas forced Jane to walk .... [ note doika jene is one element and must stay in this order ]

tomos tumori timpa jene hí jono = Thomas forced John to hit Jane ... [ note timpa jene hí jono is one element an must stay in this order ]

[Note to self : think about the below more ]. These two expressions also have alternatives ...

tomos tumori jene doika

tomos tumori jono timpa jene

[By the way ... as an example of tuma being a normal verb ... tomos jwuba komo jene tumori = Thomas squeazed Jane's left buttock ]

Two other examples of manga with auxilliary verbs (why not) ...

1) ... mbe = to hold ..... lelpa = to sing, singing ..... jenes mbor lelpa bòi = Jane can sing well.

2) ... glù = to depart ... timpa = to hit, hitting ... jonos glori timpa jene = John stopped hitting Jane

..

One notable use of the manga is emphasis, where the manga is used right next to the same word in r-form. For example ...

| daw-o-r-u | dàu |

|---|---|

| die-3SG-IND-FUT | death |

= He/she will die a death => He/she will die for sure

| lay-o-r-i | lái |

|---|---|

| live-3SG-IND-PAST | life |

= He/she lived a life => He/she had a full life

| maum-a-r-i | mauma |

|---|---|

| sleep-1SG-IND-PAST | sleep |

= I slept a sleep => I had a deep and satisfying sleep

Now maumori mauma and daw.oru dàu are strange. Both verbs are strictly intransitive. If the pronouns were to be included you would have to absolutive arguments in the clause (i.e. ò and dàu : pà and mauma) ... something that is not allowed. But it seems that béu does allow it if one of the arguments is the base of the r-form.

..

Note to self : Dixon makes a big deal over the below. [ Note to self : what sort of deal should I make ? ]

1) The killing of the president was an atrocious crime. [ Note to self : "killing" here is a noun ... as identified by "the" and "of the" ]

2) Killing the president was an atrocious crime. [ Note to self : "killing" here is not a noun ... we can call it an infinitive ... as identified by "the president" following immediately ]

You can see that one form "killing" is used in 2 different constructions.

And a further note ... "I saw a man cutting the grass" is an English clause. I think Dixon analyses "the man cutting the glass" as a complement clause ??? This sees a bit strange to me. The béu equivalent .... mwari bàu katala lazde is just analyzed as Verb mwari ... Object bàu and Adjective Phrase katala lazde

..... Feŋgi

..

The feŋgi or particles are too diverse to say anything meaningful about them here. We will learn them one by one as we go though the ten chapters.

..

But just to fill out this section a bit, I will give you two sets of pronouns. One set being the pronouns in their unmarked form* and the other ... the pronouns in their ergative form**.

Here, for a transitive clause, "that which initiates the action" is called the A argument, and "that which is affected by the action" the O argument. Also, for an intransitive verb, the noun is called the S argument. It is convenient to make a distinction between all three cases. I follow RMW Dixon in using this terminology.

In most languages the S argument is marked the same way as the A argument. However in some languages the S argument is marked the same way as the O argument. These are called ergative languages. béu is one of these ergative languages. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative.

Below are the béu pronouns for the S and O arguments. This form can be considered the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | magi | inclusive |

| us | manu | exclusive | ||

| you | gì | you | jè | |

| him, her | ò | them | nù | |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

NOTE ... Pronouns differ from nouns in that their tones change between the ergative and the unmarked form. For a normal noun it is sufficient that -s is suffixed. For example ...

..

| bàu-s | glá | timp-o-r-i |

|---|---|---|

| align=center|woman | hit-3SG-IND-PAST |

==> The man hit the woman

| bàu | glá-s | timp-o-r-i |

|---|---|---|

| man | woman-ERG | hit-3SG-IND-PAST |

==> The woman hit the man

..

Below are the pronouns in the ergative form. From now on I will call the ergative form the s-form, and the unmaked form the base form.

..

| I | pás | we | magis |

| we | manus | ||

| you | gís | you | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

jè and jés are the second person plural forms.

There is one other pronoun ... the reflexive pronoun tí. This is always an O argument. Notice that it is the only O argument with a high tone.

* In the Western Linguistic Tradition, these "forms" are called "cases". The English word case used in this sense comes from the Latin casus, which is derived from the verb cadere, "to fall", from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱad-. The Latin word is a calque of the Greek πτῶσις, ptosis, "falling, fall". The sense is that all other cases are considered to have "fallen" away from the nominative (considered the unmarked form in Latin).

** By the way, there are 17 marked forms (cases) in béu ... the ergative being one of these.

..

..... Intensifiers

..

Remember earlier in this chapter, we mentioned the numerative slot (for the senko). To recap, this slot can contain ...

nò "plural" ... ʔà "one" ... hói "two" ... léu "three" ... iyo "few" ... ega "four" ... oda "five" ..... up to ..... tautaita "172710 ... hài "many"and ú "all"

Below is show how hài and iyo divide up the semantic space of quantity(intensity).

..

..

Now all saidau(adjectives) can be affixed by -ge to form the comparative* form. For example ...

bàu jutu = "the big man" : bàu jutuge = "the bigger man"

This affix can also be used with the numbers ...

juge "more than zero", ?age "more than one" : hoige "more than two" .... up to tautaitage "more than 172710**

Now -ge can also be affixed to iyo letting us fill in every box of the chart given above ...

..

Now when attached to saidau, -ge gives a relative value (i.e. you are comparing one thing with another). However when -ge is attached to a numbers you get an absolute value (i.e. you are not comparing the modified item with anything).

When you want to compare two items as to their numerative value, you must use the particle yú.

(The word yú and the suffix -ge both can be translated as "more", however yú only qualifies nouns and -ge only qualifies adjectives)

jonos byór yú klogau jenewo = "John has more pairs of shoes than Jane"

?ár yú halmai = "I want more apples"

?ár hài halmai = "I want a lot of apples" or "I want many apples"

..

Now a number can immediately follow yú. For example ...

?ár yú léu halma = "I want three more apples"

yár yú halmai jenewo = "I have more apples than Jane" ....... [ note ... halma with léu but halmai with yú ]

..

To indicate "less" ... use wì. For example ...

jenes yór wì halmai pawo = "Jane has less apples than me"

jenes yór wì hói halma pawo = "Jane has two less apples than me" .... but it would sound better to rephrase these as ...

yár yú halmai jenewo = "I have more apples than Jane" : yár yú hói halmai jenewo = "I have two more apples than Jane"

..

*The affix -mo is the superlative for adjectives. When joined to hài and iyo ... we get "the majority" haimo and "the minority" iyomo

**Note ... the words noge, haige and uge do not exist.

..

..

Above we have talked about numeratives and in detail about how to quantify senko.

Below we will touch on how other categories of words have their own intensifiers ...

..

..

hài bàu = many men

moze hè = a lot of water

hè also can qualify verbs. As with normal adverbs, if it doesn't immediately follow the verb it must take the form hewe.

(Note to self : I can't think of a reason you would want to separate hè from its verb)

glá doikori hè = the woman walked a lot

hewe glá doikori = the woman walked a lot

báus timpori glá hewe = the man hit a woman a lot

And also can intensify manga and mangas

solbe hè moze = "to drink a lot of water"

solbe moze hè = "to drink a lot of water"

The above two forms are equally likely to be found. There is a difference in meaning but you would be a real nitpicker to worry about that.

..

saidau and saidaun are both intensified by sowe ...

jutu sowe = "very big"

jutun sowe = "the very big one"

..

Notice that mangan and saidaun can take two intensifiers ...

hài solben hè wiski = the many times a lot of whisky was drink ... hài solben hè wiski hí pà = the many times I have drunk a lot of whisky

hài gèun sowe = the many very green ones

..

We will take about the opposite of intensifiers and other quantifiers in a later chapter. These are a lot rarer. The intensifiers are the ones most commonly used.

..

..... The main derivation pathways

..

Derivational morphology often involves the addition of a derivational suffix or other affix. Such an affix usually applies to words of one lexical category (part of speech) and changes them into words of another such category. For example, the English derivational suffix -ly changes adjectives into adverbs (slow → slowly).

Examples of English derivational patterns and their suffixes:

- adjective-to-noun: -ness (slow → slowness)

- adjective-to-verb: -ize (modern → modernize)

- adjective-to-adjective: -ish (red → reddish)

- adjective-to-adverb: -ly (personal → personally)

- noun-to-adjective: -al (recreation → recreational)

- noun-to-verb: -fy (glory → glorify)

- verb-to-adjective: -able (drink → drinkable)

- verb-to-noun (abstract): -ance (deliver → deliverance)

- verb-to-noun (agent): -er (write → writer)

Derivation can be contrasted with inflection, in that derivation produces a new word (a distinct lexeme), whereas inflection produces grammatical variants of the same word.

Generally speaking, inflection applies in more or less regular patterns to all members of a part of speech (for example, nearly every English verb adds -s for the third person singular present tense), while derivation follows less consistent patterns (for example, the nominalizing suffix -ity can be used with the adjectives modern and dense, but not with open or strong).

Derivation can also occur without any change of form, for example telephone (noun) and to telephone. This is known as zero derivation. [ All the above from "wikipedia" under "linguistic derivation" ]

..

The diagram below shows the ten main derivational processes which are absolutely fundamental to the working of the language. By the way, the verbal base (equivalent to English infinitive or gerundive I think ??) should be considered a noun.

[1]

Most nouns can be used as adjectives just by placing them directly after the noun they are qualifying. Like "school bus" in English. For example ...

pintu tìa = a/the door of the house

Also to indicate possession the possessee is usually just placed after the possessed.

tìa jono = John's house

(Actually there is a particle yó joining the possessed to the possessee ... however it is rarely used. yó is also a noun meaning possessions, yái an item possessed, yáu "to have")

"John's house" => tìa yó jono .... but more usually tìa jono

This is zero derivation and is marked as ![]() in the above diagram.

in the above diagram.

[2]

gèu = green

+ gèu = the green one

?azwodus = lactose intolerant

+ ?azwodus = a/the lactose intolerant one

[3]

gèu = green

k+ gèu = the green ones

k+ gèu làu oila = six green ones

sadu = elephant

k+ sadu = elephant-kind

k+ sadu làu oila = six elephants ... well, it is legitimate to say this ... but oila sadu is so easier.

[4]

gèu = green

kuwai gèu = greenness

[5]

yubau = strong

yubako = to strengthen

pona = hot

ponako = to heat up

[6]

poma = kick (also means leg) .... pomora = He/she is kicking

pomako = to kick

However if the base noun ends in n ...

kwofan = bicycle

gàu kwofan = to (do) bicycle

[7]

pazba yubara "I am strengthening the table"

..

| pazba | yub-a-r-a |

|---|---|

| table | strengthen-1SG-IND-PRES |

ponara moze "I am heating up some water"

| pon-a-r-a | moze |

|---|---|

| "heat up"-1SG-IND-PRES | water |

[8]

tunheun kwofanaru "I will bicycle to the townhall"

..

| tunheu-n | kwofan-a-r-u |

|---|---|

| townhall-DAT | bicycle-1SG-IND-FUT |

[9]

This will be covered in detail in the next chapter. However here is a quick example ...

solbara moze "I am drinking water"

..

| solb-a-r-a | moze |

|---|---|

| drink-1SG-IND-PRES | water |

from the verb base solbe "to drink"

[10]

-s, -n, -a, -o take -is, all other endings take -s (including -ia and -ua)

saco = fast, sacois = quickly

pudus = timid (of an animal), puduʒis = timidly

yubau = strong, yubaus = strongly

..

.

For [7] and [8] if the root that is to be transformed is monosyllabic, then we need -ko as well as -r-. For example ...

..

bàu = man

bauko = to man (exact same meaning as in English)

baukara téu dí = I am manning this position.

..

gèu = green

geuko = to make green

geukara pazba dí = I am painting this table green

..

You can say, that for monosyllabic words [7] = [5] + [9] and [8] = [6] + [9].

..

..

Unadorned adjective can be used as nouns in many situations. Similar happens in many languages. For example ... klár gèu is ambiguous.

To disambiguate => klár kuwai gèu "I like greenness" / klár k+ gèu "I like the green ones" / klár + gèu "I like the green one"

.

The remaining two transformations shown on the diagram are for verbalization. Actually the affix -ko is added to all adjectives or nouns in order to make a verb. However in one circumstance this affix is not needed. This is for the r-form based on a multi-syllable adjective or noun. For example ...

..

pazba yubaku = strengthen the table (a command)

pazba yubakis = you should strengthen the table

..

ponaku moze = heat up some water (a command)

ponakos moze = he/she should heat up some water

..

bauku téu dí = man this position (a command)

baukos téu dí = he/she should man this position

naike = sharp : naikeko = to sharpen

keŋkia = salty : keŋkiko = to add salt ... when the adjective ends is a diphthong (and is non-monosylabic) the last vowel is dropped.

keŋkikara = "I am adding salt" .... note not *keŋkara ... this is because keŋkia is a derived word.

sài = colour : saiya = colourful : saiwa = colourless : saiko = to paint (maybe via *saiyako)

..

Note ... -ko is possibly an eroded version of gàu ( "to do" or "to make" ).

Note ... There seems to be a method of deriving a two place verb from a one place verb by affixing -n. For example ... diadia = "to happen" : diadian = "to cause". While this mechanism is seen all over the language I have not mentioned it in the chart above. This is because I consider it non-productive. I count daidia and diadian both as base words. In a similar way that English speakers consider "rise" and "raise" independent words, "lie" and "lay" independent words and "sit" and "set" independent words.

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences