Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

..... The 7 types of word

..

All words belong to one of the following 7 categories ...

..

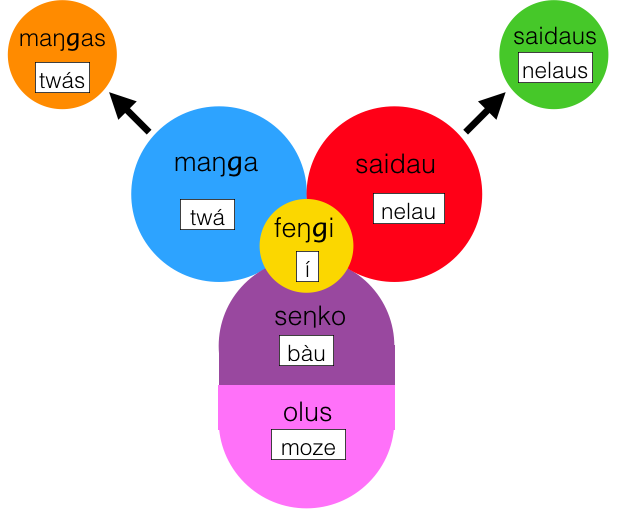

1) feŋgi = particle ... this is a sort of "hold-all" category for all words (and affixes) that don't neatly fit into the other categories. Interjections, numbers, pronouns, conjunctions, determiners and certain words that would be classed as adverbs in English, are all classed as feŋgi.

An example is Í .. the preposition indicating the dative.

..

..

2) seŋko = object

An example is bàu ... "a man"

..

3) olus = material, stuff

An example is moze ... "water"

..

4) saidau = adjective

An example is nelau ... "dark blue"

..

5) maŋga = verb

An example is twá ... "to meet" (the concept of "meet" disassociated from any arguments, tense, aspect or whatever).

..

6) maŋgas = a noun derived from a verb. A maŋgas represents one instance of the activity denoted by the maŋga. For example ...

twás ... "a\the meeting" : nò twás ... "a\the meetings"

..

7) saidaus = a noun derived from an adjective. The saidaus means one object possessing the property denoted by the saidau.

An example is nelaus = a/the dark blue one : nò nelaus = a/the dark blue ones

..

..

The maŋgas and saidaus are transparently derived from the maŋga and saidau so there is no need to list them separately in a dictionary.

..

..... The Pilamo or case system

..

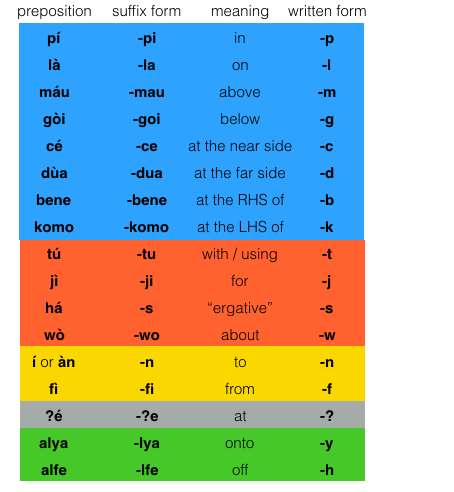

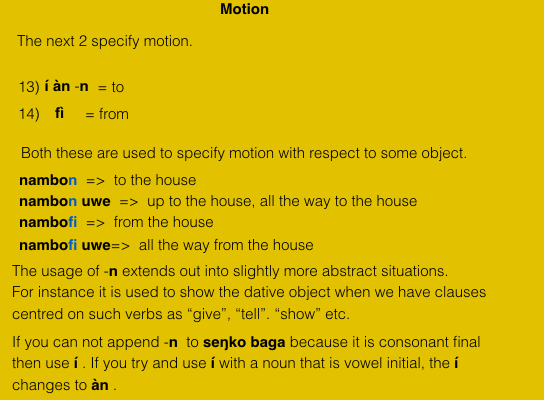

In total there are 17 cases (if you were to include the unmarked case as well the total would be 18). They are called the pilamoi.

These are attached to a noun and show the relationship of that noun with respect to the rest of the sentence.

..

The word pilamo is built up from ;-

pila (v) = to place, to position, to correctly align

pilamo ( n) = the positioner

..

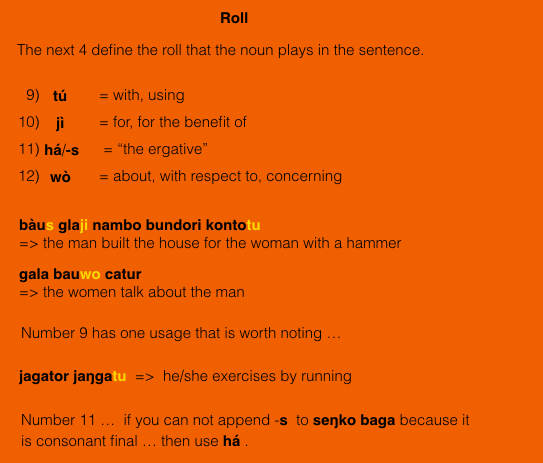

Probably the most important case is the ergative (the 11th case). In English it is the order of the verb and the arguments that shows who is the doer and what is the "done to". Namely the A and S argument come before the verb and the O argument after ... [ English is a non-ergative language and hence the A and S argument get treated in the same way.]

In béu, to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", the suffix -s is appended to the A argument. For example ...

..

glás bàu timporyə => The woman has hit the man ..... (with "the man" being the O argument)

glá bàus timporyə => The man has hit the woman ...... (with "the man" being the A argument)

bàu doikora => The man is walking ........................... (with "the man" being the S argument) ... [ béu is an ergative language and hence the O and S argument have the same form.]

..

..

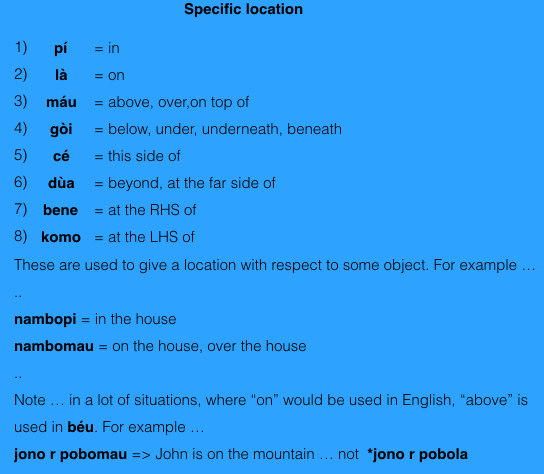

The pilamoi are either realized as either affixes or as prepositions.

Whether the pilamoi appears as an suffix or a preposition depends on seŋko * ... if seŋko baga, then the affix is used ... if seŋko kaza, then the preposition is used. For example ...

nambodua = beyond the house

dùa nambo yó yinkai hauʔe = beyond the house of the pretty girl

* or in other words, if the NP is only one word one uses the suffix, and if the NP is more than one word one uses the preposition }

..

Note on the script ... If they are realized as affixes then, in the béu script uses a sort of shorthand. That is the affix is represented as one letter.

..

Earlier we have seen that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilamo affixed to them. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilamo then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

jonos jenes solbur moze = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of an affixed pilamo, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lé should be placed between them. For example ...

jenes solbori moʒi lé ʔazwo = "Jane drank water and milk"

jonos jenes bwuri hói sadu lé léu ʔusʔa = John and Jane saw two elephants and three giraffes.

[ Compare the above two examples to há jono jene solbori moze = Jane's John drank water ... i.e. The John that is in a relationship with Jane, drank water ]

This word is that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

..

.. As parts of speech

..

pilamoi of location phrases (i.e. nouns with 1 -> 8 or 15) can be considered adjectives if they come after a noun and adverbs if they come after a verb. They must come after a noun or a verb. Sometimes they come after the copula*. In this case they are adjectives. Now often the copula is dropped ... but if this dropping results in any ambiguity it can be readily "undropped".

pilamoi of motional phrases (i.e. nouns with 13, 14, 16 or 17) can be considered adverbs. They can come in any position because it is understood that they are qualifying the verb.

pilamo phrases defining sentence rolls (i.e. nouns with 9, 10, 11 or 12) can come anywhere. They are considered nouns.

* [ Notice that in English, you can either say ... "a bird is in the tree" or "in the tree is a bird"

In béu only jwado r ʔupaiʔe is valid ... also note that in this case jwado is not definite because it is left of the verb. That rule doesn't work with the copula. ]

..

..... Seŋko

..

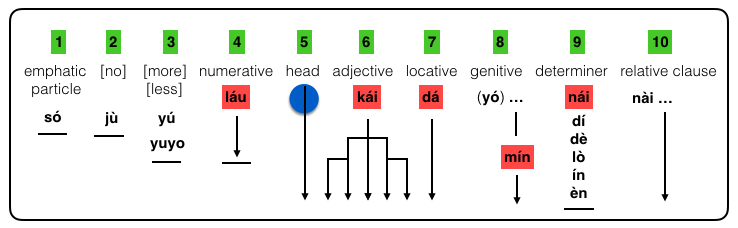

seŋko is a noun or a noun phrase

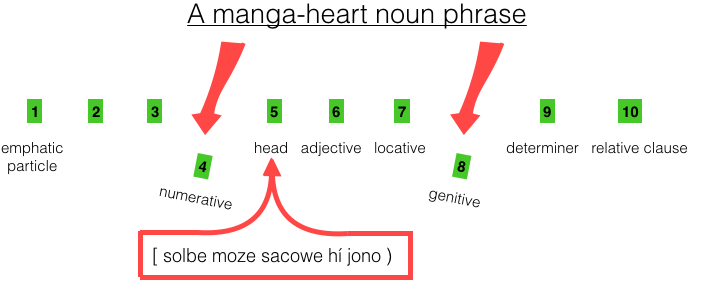

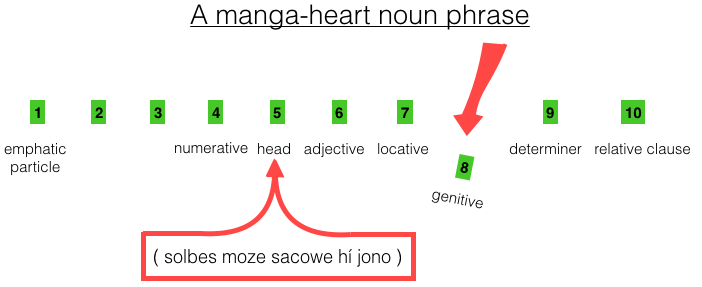

All the elements in it can be thought of fitting into 10 slots.

Below these slots are shown ...

..

..

Slots 1, 2 have only one value. Slot 3 has two. Slot 4 is restricted to 173110 values and slot 9 to six.

The words highlighted in red convert the noun phrase (or indeed the sentence in which the NP is embedded) into a question. A blue circle indicates the only mandatory element. Branching arrows indicate multiple possibilities.

..

... The head

..

Nothing to say here.

..

... The adjective

..

6) ... the adjective

More than one adjective is allowed. For example ... bàu gèu tiji = the little green man

kái "what type" can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu kái = what kind of green man ? ... noun phrase question

há bàu gèu kái glà timpori = what kind of green man hit the woman ? ... sentence question

Numbers can go in this slot also. When in this slot they are ordinal numbers. This is opposed to where the number comes before the head, in which case it is a cardinal number. For example ...

há bàu hói glà timpori = The second man hit the woman

há hói bàu glà timpori = The two men hit the woman

..

Now when you have multiple adjectives they will have a certain order depending upon their sub-category.

This is the same as English ... for example, you always say "the third big black dog" and never "the black third big dog".

béu uses the exact same order as in English but reversed timewise. For example ...

| waulo | àu | jutu | léu |

|---|---|---|---|

| dog | black | big | third |

..

Or, you can say, béu has exactly the same order as English, in terms of proximity to the head.

..

... The locative

..

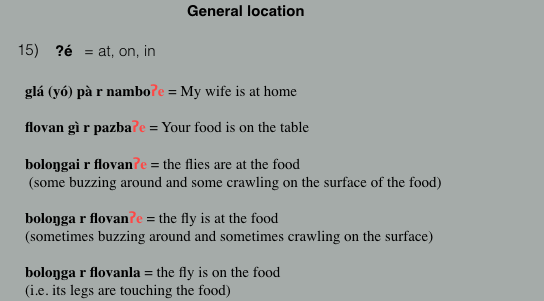

7) ... the locative. For example ... bàu gèu tiji pobomau = the little green man on top of the mountain

A locative comprises of a noun plus one of the nine affixes .... pi la mau goi ce dua bene komo ?e

The locative is a type of adjective.

Also a noun plus the affix fi can appear in this slot. This is not giving information about "location" but rather "origin". It is classed as a locative nevertheless.

Only pilamo locatives allowed in the locative slot.

duzu pobomau = The oryx on the mountain

If the location consists of two words, the usual rule applies and the pilamo appears as a preposition ...

duzu máu pobo jutu = The oryx on the big mountain

There is a tendance that the longer the locative phrase, the more likely the location will be shunted into a relative clause ...

duzu nài r máu pobo hau?e jutu = The oryx on the big beautiful mountain

All prepositions that are not pilamo lead to the location being shunted into a relative clause. For example ...

polgamo nài r bain gwai.a = The sailing boat among the islands

(Note to self : maybe I should put the pilamo section before this one)

Also dá "where" can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu dá = where is the green man ?

..

... The genitive

..

8) ... the genitive. For example jwado gèu nambomau yó jene = Jane's big green bird on top of the house

Note that the particle yó is usually dropped when the possessor is next to the head. However as other elements intervene, the likelihood that yó is used increases.

If mín (who) is used instead of jene in the above ... then we would have a question ...

jwado gèu nambomau yó mín = Whose big green bird on top of the house ? = Whose's the big green bird on top of the house ?

..

... The determiner

..

9) ... the determiner

There are five determiners ... dí (this) and dè (that). For example ...

bàu gèu tiji pobomau dé = that little green man on top of the mountain.

The primary meaning is for comparing two objects that can be seen. Perhaps accompanied by gestures, dé will be appended to the further of the two objects and by way of distinction, dí will be appended to the nearer one. Used very rarely compared to "this" and "that" in English.

nái (which) can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu tiji nái = which little green man ? ... noun phrase question

bàu gèu tiji nái glà timpori = which little green man hit the woman ? ... sentence question

lò "other" appear in this slot ... bàu gèu tiji lò = "the other little green man" or "another little green man"

èn "some" appear in this slot ... bàu gèu tiji èn = "some little green man" ...... indefinite

ín "any" appear in this slot ... bàu gèu tiji ín = "any little green man" .............. super indefinite

..

Note ... dían = "here" or "to here", dèn = "there" or "to there" ... (not *dà dí and *dà dè)

( dí and dè can represent direct speech. The appear in conjuction with one of the quotative verbs swé or aika. dè refers back to an utterance already spoken, dí to an utterance that is imminent (see Ch 3.7 ??? )

One little rule ... if a genitive is present, the determiners dí and dè can not be included. However dían "here" and dèn "there" can occur in the "locative" slot and we get the same meaning. If a genitive is absent, we do not get dían and dèn in the locative slot. Also if ló or nái are present dí and dè can not be included but dían "here" and dèn "there" can occur in the "locative" slot.

..

... The numerative

..

4) ... the numerative

These are ...

nò "plural" ... ʔà "one" ... hói "two" ... léu "three" ... iyo "few" ... ega "four" oda "five" ..... hài "many" .... tautaita (172710) and ú "all"

Only one word is allowed in the numerative slot*.

..

láu (how many) can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole sentence into a question. For example ...

láu bàu (r) pobomau = How many men (are) on top of the mountain ? .... **

With more complex seŋko baga it is usual to break it up in order to specify exactly which element is being questioned. For example ...

láu bàu gèu tiji pobomau nài doikura = " How many little green men on the mountain that are walking? " ... would be re-phrased as ...

wò bàu gèu tiji pobomau _ láu doikura = w.r.t. the little green man on top of the mountain, how many are walking ? ... or ...

wò bàu tiji pobomau nài doikura _ láu r gèu = w.r.t. the little man on top of the mountain who are walking, how many are green ?

Note ... in the 2 examples above, fì can be substituted for wò. However wò is more felicitous.

..

*So how do we translate "all four men" or "none of the men". Well in depends on the situation ... for example ... imagine a story when one man meets three men, after a discussion they decide to go somewhere together. In English, the first S or A argument after they join up would be "all four men" or just "all four". In béu you would use egas "the foursome".

In another situation "all four man" would be translated using the "partitive particle" làu. So ... "all four men" would be ega bàu làu ú.

In a similar way to three out of the four men would be ega bàu làu léu. [ Note ... short for ega bàu làu léu bàu so never *ega bàu làu ubas]

"none of the four men" => ega bàu làu jù

..

**Notice that in English and béu the copula can be dropped. In béu, when we drop the copula, what is left is analized as a NP (as opposed to a clause)

..

... The relative clause

..

10) ... the relative clause

(Note to self : maybe this should be moved to further down)

Relative clauses "RC" work pretty much the same as English relative clauses. The relativizer is nài (that, who). Here are some examples ...

yiŋkai nài doikoryə = the girl that has walked

bàu nài glás timporyə = the man whom the woman has hit

glá nàis bàu timporyə = the woman who has hit the man

bàu nàin glás fyori yiŋkaiwo = the man to whom the woman told about the girl

glá naiji bàus bundoryə nambo = the woman for whom the man has built a house

All the pilamo can be appended to the relativizer to specify what roll the noun would have in the relative clause if it was a simple clause.

..

... The emphatic particle

..

1) ... the emphatic particle is só.

só is used where we would use what is called "right dislocation" in English. For example ...

bàus só glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.

bàus só glán nori alha @ = Is it the woman to whom the man gave flowers ?

só might be used in exasperated when somebody can not see something. For example ...

| só dí | "this one !" | só dè | "that one !" |

| só nò dí | "these ones!" | só nò dè | "those ones !" |

This can also used as a sort of vocative case ... not obligatory but can be used before a persons name when trying to get their attention. For example ...

só jene = Hey, Jane

só gì = Hey, you

There is an adjective intensifier sowe "very" ... no doubt related to the above.

..

... "no", "more" and "less"

..

jù = "no" .... if slot 2 is filled, then slot slot 4 must be empty.

yú = "more"

yuyo = less ... (maybe yuyo < yú iyo)

..

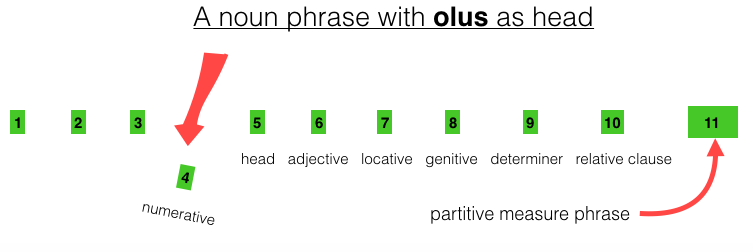

..... Olus

..

In this category are such uncountable things such as "water" moze.

..

A NP with olus as head is similar to a NP with seŋko as head, except the numerative is discarded. A "partitive measure phrase" can be added if you want to specify the quantity.

hói hoŋkoi "two cups" ... is a typical "measure phrase" and làu is the "partitive particle".

So ... an example of a NP with olus as head ...

?azwo pona làu hói hoŋkoi "two cups of warm milk"

Two extra adjectives are admitted into the adjective slot ... hè "a lot of" and iyo "a little" (Yes ... iyo was formerly in the numerative slot meaning "few")

..

A few hundred words have a dual existence. With final vowel can be e u a o or i (the last one is especially common) they have a collective meaning. For example ...

| bodi | py-o-r |

|---|---|

| birds | fly-3SG-IND |

=>small birds fly ................. [notice the third person singular agreement on the verb]

However with a change of the final vowel to ai these concepts become countable.

| bodai | lail-o-r-a |

|---|---|

| a small bird | sing-3SG-IND-PRES |

=> a small bird is singing

Which can be made plural by putting a number in front (or one of the other numeratives).

| léu | bodai | lail-u-r-a |

|---|---|---|

| three | small bird | sing-3PL-IND-PRES |

=> three small birds are singing

Note .... the singular of some nouns also end in -ai. For example moltai "doctor". These words take a plural by adding an a ... moltai.a "doctors". However the nouns ending in -ai that have a collective equivalent, never mark plurality on the actual word. So "little birds" is nò bodai rather than *bodai.a.

..

| bodi | birds** | bodai | a small bird |

| fiʒi | fish | fizai | a fish |

| yinki | crumpet | yinkai | a young unmarried woman, an attractive girl, a virgin |

| toti | children | totai | a child |

| wazbo | distance | wazbai | 3,680 m (the unit of distance ... the béu km or mile) |

| malkufa | cabbages | malkufai | a cabbage |

..

So there a bunch of concepts that have a dual identity ... sometimes appearing in their olus form, and sometimes appearing in their seŋko form.

..

Remember that all collectives take singular pronouns and, if they are A or S arguments, produce an -o- in slot 1 of the verb (as opposed to -u-).

..

There is a prefix -kai, that can theoretically change any seŋko into an olus. In practice it is not used that much ... although you do hear it a lot prefixed to animal names ... like when talking about characteristics which are common to an entire species. For example ...

sadu "elephant" ... kaizadu "the elephants" or "elephants" ... as in kaizadu r jodo jini "the elephant is an inteligent animal"

** Birds smaller than pidgeons are bodi. Birds that are pidgeon size and above are jwadoi (the singular being jwado).

..

..... Saidaus

..

saidaus is a noun or noun phrase derived from a adjective.

..

..

You can see that the elements that surround the head are the exact same elements that surround seŋko head.

There is one tiny difference though. The word sowe "very" which usually modifies adjectives can if fact become an adjective itself and modify a saidaus. For example ...

gèu = green, gèu sowe = very green => gèus = a/the green one, gèus sowe = a/the very green one ... whereas sowe never modifies seŋko.

..

Actually saidaus can be derived from "locatives" and "genitives" as well. For example ...

pobomaus = the one on top of the mountain

yós jene = the one belonging to Jane

..

By the way ... determiners and relative clauses can also stand by themselves, but they are unmodified when they do so.

..

..... Maŋga

..

This corresponds to what is called the "infinitive" in the Western Linguistic tradition or the "masDar" in the Islamic Linguistic tradition.

Let us take solbe meaning "to drink" as an example of a maŋga.

Now phrases can be built up around maŋga. For example ...

solbe saco = "to drink quickly" or "drinking quickly"

or ... adding more elements ...

solbe moze sacowe = "to drink the water quickly" or "drinking the water quickly"

Note that what is the S or O argument in an active clause, in a maŋga phrase, must immediately follows the maŋga. Also because saco no longer immediately follows the maŋga, it must be explicitly tagged as an adverb be the -we suffix.

or ... adding even more elements ...

solbe moze sacowe hí jono = "John drinking the water quickly" or "for John to drink the water quickly".

Note that what is the A argument in an active clause, in a maŋga phrase, comes last and has the particle hí in front of it. (the particle hí is probably related to the particle há somehow)

Note ... other clausal elements ( dative object, time, adverb, instrument, reason, purpose) can be added ... in our example they would come between sacowe and hí.

And we can expand the maŋga phrase even more ... it can become the head of what we defined before as the seŋko phrase.

The seŋko phrase is slightly modified in that the numerative slot and the genitive slot must be empty.

In the example we are using sacowe "quickly" can be taken out of the heart, and placed in the seŋko phrase as saco. In the adjective slot of course.

Also you have a choice as to where you can place any locative. A locative can be placed in the locative slot of the seŋko phrase, or they can be placed in the heart, just before hí. For example ...

solbe moze sacowe nambofi hí jono = "John drinking the water quickly in the house" or "for John to drink the water quickly in the house".

Note ... in a maŋga phrase, we can not show definiteness by placing an argument before or after the verb (well actually only the S A and O arguments can be tagged for definiteness in this way). All arguments are assumed to be definite if bare, if the have èn "some/a" in front of them, they are indefinite.

..

All pilamo can be appended to maŋga ... but most don't make much sense ... however -tu and -la appear often.

tore doikatu = "he/she came on foot" or "he/she came by walking"

The -la usuage produced an adjective meaning ... "verbing" at the moment of speach. As with all adjectives it can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu doikala = a/the walking man

bàu r doikala = a/the man is walking

Note ... bàu r doikala means exactly the same as bàu doikora.

..

..... Maŋgas

..

English is very chaotic as to the various means it derive nouns from verbs. For example ... "discover" + "y" => the discovery ... "destroy" + "tion" => the destruction ... "run" + ∅ => the run.

béu is a lot more orderly.

maŋgas are similar to maŋga but defining a specific instance of the action rather than the action in general. Derived from maŋga by appending -s. If the maŋga is not vowel final, -os is appended.

..

solbe = "to drink" or "drinking" => solbes = "the drinking"

dàin = "to kill" or "killing" => dainos = "the killing", "the assassination"

..

..

For maŋgas the wider NP can contain numeratives. For example ...

hói solbes moze sacowe hí jono = "those two times that John drank the water quickly"

In fact, if you come across "times that"in an English text, inevitably it is translated by "numerative" + maŋgas.

..

pilamo can be appended just as to a normal NP but some are not appropriate. For example none of the pilamo of location are appropriate. há is put in front to show ergativity (when maŋgas acts as an A argument)

One pilamo that is often found with maŋgas is -pi. For example ...

..

jono lailore doikaspi = "John sang while walking earlier today"

jono lailore pí doikas tunheun = "John sang while walking to the civic centre earlier today"

..

It can be difficult for an English speaker to grasp the difference between maŋgas and maŋga. In English the semantic difference is often expressed using the definite article. For example ...

..

solbe moze hí fanfa = a horse drinking water

solbes moze hí fanfa = the drinking of the water by the horse

..

maŋgas and maŋga both can appear as S, A, O, CS and CO arguments ... depending of course on whether we are talking about one specific act or the action in general.

However it is always maŋga that appear in verb complements. (Note to self ... maybe we can continue the maŋga/ maŋgas distinction into the complement). For example ...

..

tomo tumori doika jene = Thomas forced Jane to walk .... [ note doika jene is one element and must stay in this order ]

tomo tumori timpa jene hí jono = Thomas forced John to hit Jane ... [ note timpa jene hí jono is one element an must stay in this order ]

..

Above are examples with intransitive and transitive maŋga respectively.

By the way, when the O argument is seŋko, tuma is a regular verb, meaning it "to squeaze". For example ...

tomos komo jwuba jene tumori = Thomas squeazed Jane's left buttock

..

1) ... blèu = to hold ..... laila = to sing, singing ..... jenes blor laila bòi = Jane can sing well.

2) ... cùa = to depart ... timpa = to hit, hitting ... jonos cori timpa jene = John stopped hitting Jane

Note to self : Dixon makes a big deal over the below .... think about it again.

1) The killing of the president was an atrocious crime.

2) Killing the president was an atrocious crime.

You can see that one form "killing" is used in 2 different constructions. By the way ... "killing" in (1) is considered more noun-like.

..... Saidau

..

The saidau has two uses in the béu. It can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu gèu = a/the green man

bàu r gèu = a/the man is green

gèu above is a simple adjective. Adjective phrases exist as well.

First there are a number of particles which are placed after an adjective to modify its degree.

Foe example gèu sowe "very green"

Secondly nearly every verb can produce an adjective by the suffixing of la to give the "present participle". For example doika "to walk" or kata "to cut" produce doikala "in the process of walking" and katala "in the process of cutting". When derived from a transitive verb the object can be icluded as well. For example katala lazde "in the process of cutting the grass".

Note ... objects (in an equivalent active clause) can take these participles as well. For example ... lazde jwola kata "grass being cut" ... jwola kata being classed as an adjective phrase as well.

..

Note .... bàu katala lazde = bàu nàis katora lazde .................. however the first ... bàu katala lazde is nearly always preferred.

Also note ... pà r katala lazde = (pás) katara lazde .............. however the second ... katara lazde is nearly always preferred.

In both cases the briefer version is chosen.

..

And a further note ... "I saw a man cutting the grass" is an English clause. I think Dixon analyses "the man cutting the glass" as a complement clause ??? This sees a bit strange to me. The béu equivalent .... bwari bàu katala lazde is just analyzed as Verb bwari ... Object bàu and Adjective Phrase katala lazde

..

..... Feŋgi

..

The feŋgi or particles are too diverse to say anything meaningful about them here. We will learn them one by one as we go though the ten chapters.

..

But just to fill out this section a bit, I will give you two sets of pronouns. One set being the pronouns in their unmarked form* and the other ... the pronouns in their ergative form**.

Here, for a transitive clause, "that which initiates the action" is called the A argument, and "that which is affected by the action" the O argument. Also, for an intransitive verb, the noun is called the S argument. It is convenient to make a distinction between all three cases. I follow RMW Dixon in using this terminology.

In most languages the S argument is marked the same way as the A argument. However in some languages the S argument is marked the same way as the O argument. These are called ergative languages. béu is one of these ergative languages. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative.

Below are the béu pronouns for the S and O arguments. This form can be considered the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | wìa | inclusive |

| us | yùa | exclusive | ||

| you | gì | you | jè | |

| him, her | ò | them | nù | |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

NOTE ... Pronouns differ from nouns in that their tones change between the ergative and the unmarked form. For a normal noun it is sufficient that -s is suffixed. For example ...

..

| bàu-s | glá | timp-o-r-yə |

|---|---|---|

| align=center|woman | hit-3SG-IND-PRF |

==> The man has hit the woman

| bàu | glá-s | timp-o-r-yə |

|---|---|---|

| man | woman-ERG | hit-3SG-IND-PRF |

==> The woman has hit the man

..

Below are the pronouns in the ergative form.

..

| I | pás | we | wías |

| we | yúas | ||

| you | gís | you | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

jè and jés are the second person plural forms.

There is one other pronoun ... the reflexive pronoun tí. This is always an O argument. Notice that it is the only O argument with a high tone.

* In the Western Linguistic Tradition, these "forms" are called "cases". The English word case used in this sense comes from the Latin casus, which is derived from the verb cadere, "to fall", from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱad-. The Latin word is a calque of the Greek πτῶσις, ptosis, "falling, fall". The sense is that all other cases are considered to have "fallen" away from the nominative (considered the unmarked form in Latin).

** By the way, there are 17 marked forms in béu ... the ergative being just one of these 17.

..

..... Intensifiers

..

Remember earlier in this chapter, we mentioned the numerative slot (for the senko). To recap, this slot can contain ...

nò "plural" ... ʔà "one" ... hói "two" ... léu "three" ... iyo "few" ... ega "four" ... oda "five" ..... up to ..... tautaita "172710 ... hài "many"and ú "all"

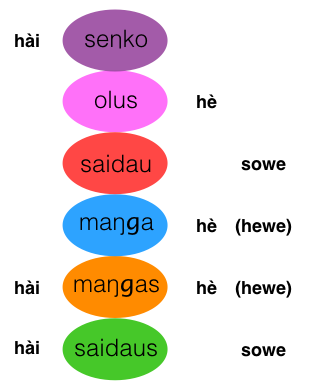

Below is show how hài and iyo divide up the semantic space of quantity(intensity).

..

..

Now all saidau(adjectives) can be affixed by -ge to form the comparative* form. For example ...

bàu jutu = "the big man" : bàu jutuge = "the bigger man"

This affix can also be used with the numbers ...

juge "more than zero", ?age "more than one" : hoige "more than two" .... up to tautaitage "more than 172710**

Now -ge can also be affixed to iyo letting us fill in every box of the chart given above ...

..

Now when attached to saidau, -ge gives a relative value (i.e. you are comparing one thing with another). However when -ge is attached to a numbers you get an absolute value (i.e. you are not comparing the modified item with anything).

When you want to compare two items as to their numerative value, you must use the particle yú.

(The word yú and the suffix -ge both can be translated as "more", however yú only qualifies nouns and -ge only qualifies adjectives)

jonos byór yú klogau jenewo = "John has more pairs of shoes than Jane"

?ár yú halmai = "I want more apples"

?ár hài halmai = "I want a lot of apples" or "I want many apples"

..

Now a number can immediately follow yú. For example ...

?ár yú léu halmai = "I want three more apples"

yár yú halmai jenewo = "I have more apples than Jane"

..

To indicate "less" ... use yú iyo***. For example ...

jenes yór yú iyo halmai pawo = "Jane has less apples than me"

jenes yór yú iyo hói halmai pawo = "Jane has two less apples than me" .... but it would sound better to rephrase these as ...

yár yú halmai jenewo = "I have more apples than Jane" : yár yú hói halmai jenewo = "I have two more apples than Jane"

..

*The affix -mo is the superlative for adjectives. When joined to hài and iyo ... we get "the majority" haimo and "the minority" iyomo

**Note ... the words noge, haige and uge do not exist.

***I guess the existence of yú iyo mucks up the 10 slots I have worked out for the NP (Note to self : yú iyo => yuyo ?)

..

..

Above we have talked about numeratives and in detail about how to quantify senko.

Below we will touch on how other categories of words have their own intensifiers ...

..

..

hài bawa = many men

moze hè = a lot of water

hè also can qualify verbs. As with normal adverbs, if it doesn't immediately follow the verb it must take the form hewe.

(Note to self : I can't think of a reason you would want to separate hè from its verb)

glá doikori hè = the woman walked a lot

hewe glá doikori = the woman walked a lot

báus timpori glá hewe = the man hit a woman a lot

And also can intensify manga and mangas

solbe hè moze = "to drink a lot of water"

solbe moze hè = "to drink a lot of water"

The above two forms are equally likely to be found. There is a difference in meaning but you would be a real nitpicker to worry about that.

..

saidau and saidaus are both intensified by sowe ...

jutu sowe = "very big"

jutus sowe = "the very big one"

..

Notice that mangas and saidaus can take two intensifiers ...

hài solbes hè wiski = the many a lot of whisky was drink ... hài solbes hè wiski hí pà = the many I have drunk a lot of whisky

hài gèus sowe = the many very green ones

..

We will take about the opposite of intensifiers and other quantifiers in a later chapter. These are a lot rarer. The intensifiers are the ones most commonly used.

..

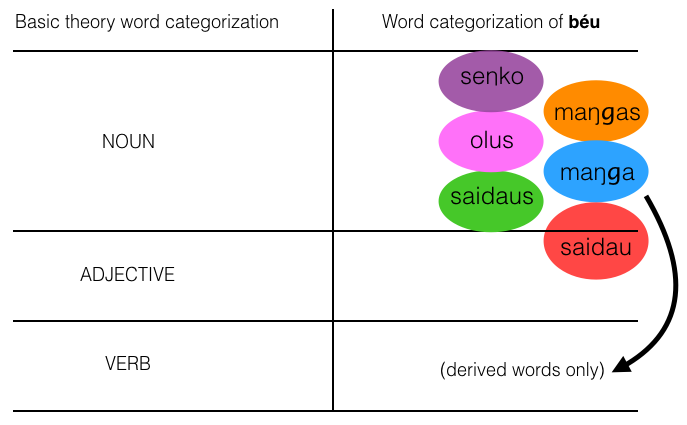

... The 7 types versus basic types

..

I have heard of people constucting languages and their main aim from the start was to create a language that contained only nouns or only verbs or what have you. I have always considered this a bit silly ... however it appears that I have arrived at such a position myself ... well at least as to the non-derived (basic form) of the words*.

..

..

The base form of béu verbs are the maŋga which you can consider an "infinitive" or a "verbal noun". "MaSdar" if you will. To get a finite verb [called a "hook word" in béu] it must go through a derivational process [see Ch 3.1 for more information].

The béu adjectives seem to straddle two categoties ... nouns and adjectives. For example gèu means both "green" and "greenness" ("the green one" is represented by the saidaus gèus). But this is similar to many languages. For example in the English phrase "green is good", "green" must be a noun.

In béu (as in English) gèu will most often occur as an adjective. In béu when gèu must appear as a noun in a position where it might be mistaken for an adjective it is put into a NP with head kuwai ... kuwai = property, quality, attribute, characteristic, feature. So kuwai gèu is a NP meaning "greenness". In English when "green" must appear as a noun in a position where it might be mistaken for an adjective, it is changed into a noun with the affiX "ness" of course.

By the way ... there is one sure way to check if a word is saidau or not. If a word can take the intensifier sowe then the word is saidau (or a saidaus but you know it is saidau if it doesn't end in s)

(Note to self ... what béu word class is kuwai )

As a theoretical basis I am following Basic Theory as forwarded by RMW Dixon in his trilogy of the same name. I don't consider béu to diverge from Basic Theory. Just some of my categories are sub-categories of Basic Theory categories.

*In the chart we are ignoring grammatical words ... the fengi.

..

... Questions

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 8 question words ... "which", "what", "who", "whose", "where", "when", "how" and "why". *

..

..

If you hear any of these words you know you are being solicited for some information. These words have no other function apart from asking questions.

..

Notice that there is no word for "how" or "why" in the above table. These are expressed by wé nái and nenji** respectively.

On the other hand, béu has single words where English has "how much" and "what kind of".

..

The first two have dual forms ... nén and mín are the absolutive forms and nós and mís are the ergative forms.

..

Now ʔai? always comes utterance final ... ʔala always comes between two NP's. This leaves 7 QW's. Of these nén mín dá and kyú are fronted***

And láu kái dá and nái **** are found in their respective slots within a NP ...

Note that when questioning who owns something yó mín occurs within the NP ... this is a sort of secondary usuage of mín and is not considered here.

Also note that dá can be either fronted or within a NP. When fronted it asked where the action takes place. When within a NP it asks about the NP's location. For example ...

..

| jene-s | halma | dá | hump-o-r-u |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jane- ERG | apple | where | eat-3SG-IND-FUT |

=> where is the apple that Jane will eat

A suitable answer to the above is pazbala "on the table"

| dá | jene-s | halma | hump-o-r-u |

|---|---|---|---|

| where | Jane- ERG | apple | eat-3SG-IND-FUT |

=> where will Jane eat the apple

A suitable answer to the above is pazba?e "at the table"

..

Statement .... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 .... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 .... í mín bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 .... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... bàus glán nori láu alha = How many flowers did the man gave the woman ?

Question 5 ... bàus glán nori alha kái = What kind of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 6 ... dá bàus glán nori alha = Where did the man give the woman flowers ?

Question 7 ... kyú bàus glán nori alha = When did the man give the woman flowers ?

Question 8 ... í glá nái bàus nori alha = to which woman did the man gave the flowers ?

Question 9 .... há bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 10 .... bàus glán nori alha ʔala cokolate = Did the man gave the woman flowers or chocolate ?

Question 11 ... ʔír doika ʔala jaŋka = Do you want to walk or run

Question 12 .... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 13 ... minji bàus glán nori alha = Why did the man give the woman flowers ?

..

*Note ... there was also a "whom" until quite recently. Also some people count "whose" as a separate QW ... however it shouldn't be ... it is just "who" + "z" (the genitive clitic).

**Well nenji is the normal traslation of "why". In certain situations you might hear minji ... when it is knows that an action/state is for somebody's benefit and no other reason is applicable.

***Around one third of the world's languages front a question word. English is one of them. [ see http://wals.info/feature/93A#2/25.5/151.2 ]

****Actually these 4 words often stand alone. But when they do, they are still considered within a NP ... only that the rest of the NP has been dropped.

..

In the table of question words above I have marked the top two and the bottom two off. The top two because they are the QW's par excellence ... they are used more than the other QW's. The bottem two because their answers are restricted to two items. ?a is restricted to "yes" or "no" ... ?ala to one of the NP's that sandwich it.

láu kái dá kyú and nái each have low tone equivalents. These particles are important grammatical words in their own right and they each are related to their high tone equivalent in subtle ways. Basically làu introduces the "partitive construction" , kài means "like" or "similar", dà introduces an adverbial phrase of location, kyù introduces an adverbial phrase of time, and, nài is a "relativizor".

... nài

..

In English "who", "that" and "which" are relativizors ... a particle that introduced a relative clause. For example ...

"The man who ate the chicken"

"The chicken that was eaten"

"The knife and fork which were used to eat the chicken"

..

In béu there is only one relativizer, which is nài. For example ...

glá nài bàu timpori = "The woman who the man hit"

Now ... in the above ... glá is being modified by nài bàu timpori. nài bàu timpori implies a clause bàu timpori glà.

To construct a relative clause for glá, nài is inserted between the noun and clause, and the noun is dropped from the clause.

Now in the above example ... the roll of glá in the clause is absolutive (i.e. glá is unmarked). However if the roll of the noun ... in the clause ... is one defined by one of the 17 pilamo, this pilamo must be suffixed to nài. For example ...

..

pi ... the basket naipi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

la ... the chair naila you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

... mau / goi / ce / dua / bene / komo ...

tu ... báu naitu ò is going to market is her husband = the man with which she is going to town is her husband ... kli.o naitu he severed the branch is rusty

ji ... The old woman naiji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

-s ... báu nàis timpori glá_rò jutu sowe = The man that hit the woman is very big.

wo ... The boy naiwo they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

-n ... the woman nàin I told the secret, took it to her grave.

fi ... the town naifi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

?e ... nambo naiʔe she lives is the biggest in town = the house in which she lives is the biggest in town

-lya ... the boat nailya she has just entered is unsound

-lfe ... the lilly pad nailfe the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond ... (note to self : improve this, work out translation for all these concepts)

..

If the roll of the noun (in the clause) is one not specificated by the 17 pilamo then the noun can not be dropped entirely, it must be represented by a pronoun. For example ...

| gwài | nài | polg-u-r-a | ala | ʃì |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| the islands | REL | sail-1PL-IND-PRES | between | them |

Literally "the islands that we are sailing between them" ... or ... in good English ... "the islands that we are sailing between"

| gawa | nài | toto-s | lent-o-r-e | tài | nù |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| the women | REL | children-ERG | play-3SG-IND-PAST | in front of | them |

Literally "the women that the children played in front of them" ... or ... in good English ... "the women that the children played in front of"

..

| há | gawa | nài | toto-s | lent-o-r-e | tài | nù | waulo | dainuru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERG | the women | REL | children-ERG | play-3SG-IND-PAST | in front of | them | dog | kill-3PL-IND-FUT |

Literally "the women that the children played in front of them, will kill the dog" ... or ... in good English ... "the women that the children played in front of will kill the dog"

..

In English we have what is called a headless relative clause. béu has this also ...

nài bwair r nài mair = "what you see is what you get"

nàis bwor r nàis mair = "that which sees is that which gets"

ò nàis bwor r ò nàis mor = 'he that sees is he that gets" ... [this one not headless of course ... a pronoun has been added to narrow down what exactly we are talking about]

..

... kyù

..

kyù = when

toili gìn naru kyù twairu = I will give you the book when we meet ............................ kyù twairu can be considered an adverb of time.

..

... dà

..

dà = where

pà twahu dà yildos twaire = meet me where we met in the morning ........................ dà yildos twaire can be considered an adverb of place.

..

... kài

..

kài = as, like

| jono | r | kài | dada | ò |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| john | is | like/as | older brother} | his |

=> John is like his older brother .................................................................... in this example kài and what follows can be considerd an adjective.

| jono | r | kài | dada |

|---|---|---|---|

| john | is | like/as | older brother} |

=> John is like my older brother .................................................................... in this example kài and what follows can be considerd an adjective.

...

| jono-s | klud-o-r | kài | tomo-s | klud-o-r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | writes-3SG-IND | like/as | thomas-ERG | writes-3SG-IND |

=> John writes like Thomas writes ........................................................ in the following examples kài and what follows can be considerd an adverb of manner.

| jono-s | klud-o-r | kài | tomo-s |

|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | writes-3SG-IND | like/as | thomas-ERG |

=> John writes like Thomas ...........................................Note ... the final verb has been dropped but Thomas keeps the ergative marking.

| jono-s | huz-o-r | kài | kulumo |

|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | smoke-3SG-IND | like/as | chimney |

=> John smokes like a chimney

| taud-o-r-a | kài | hunwu | tú | húa | gayana |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to be annoyed-3SG-IND-PRES | like/as | bear | with | head | aching |

=> he/she is annoyed like a bear with a headache

(Note to self .... is gayana still valid)

| bù | ?oim-o-r-a | kài | fiʒi | mù | moze |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| not | to be happy-3SG-IND-PRES | like/as | fish | out | water |

=> he/she is unhappy like a fish out of water

| gì | r | gombuʒi | kài | jono |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| you | are | argumentative | like/as | John |

=> you are argumentative like John .............................. i.e. in the same manner ... for example ... shouting over other people when they try and put forward their arguments

Note ... the wide variety of things being compared ... clause to clause : clause to noun : noun to noun

..

... làu

..

Question ... ò r láu bòi "how good is he ?"

Answer .... ò r làu bòi jonowo "he is as good as John"

làu means "to such an extent or degree" and is used in front of adjectives. The below are all single clauses.

..

jono r làu bòi jenewo = "john is as good as jane"

tomo r làu fat _ plùa bù blòr doika = "thomas is so fat that he can not walk"

ʔazwo pona làu hói hoŋko = two cups of hot milk

..

There are three main usages for this particle. The three examples above demonstrate these three usages. ..

..

Note ... all the above should be actually two clauses but because of truncation ... [ a chimney ] <= [ a chimney smokes ] ... [ before ] <= [ she used deceit before ] ... [ John ] <= [ John is argumentative ] ... [ agreed ] <= [ all parties agreed ] ... [ John ] <= [ John is ] ... these constructions often appear as if only a NP follows kài.

Usually for particles that can either be followed by a NP or a clause, I add gò after the particle when a clause follows. This is to prevent errors in comprehention. For example jì means "for" and is followed by a NP (usually a person). I have jì gò meaning "in order that" ... jì gò being followed by a clause. In béu the first word of a clause is often a noun. If I had jì meaning "in order that" there might be misunderstanding (albeit temporary). English does this also in many constructions [ I should go into this more fully ??? ]. Of course I could have a totally different particle for "in order that" but I wanted to emphasis the semantic overlap between these to constructions.

But there is no chance of misunderstanding when kài is heard ... it is always followed by a clause. Even in (5) what we have is a clause. The clause is jono r (with the r dropped). Actually kài means "in the manner or roll specified" ... the last bit added to include cases like (5).

..

Note ... kài can not be followed by an adjective.

There are 5 nouns that are associated with 5 of these above question word / indefinite pairs. làus = amount, quantity : kàin = kind, sort, type : dàs = place : kyùs accasion, time : sàin = reason, cause, origin

These 5 nouns are never followed by nài. The table below is interesting. It shows the logical equivalence of a hypothetical expession (on the LHS) and the logical equivalent actually used (on the RHS).

..

*làus nài => làu

*kàin nài => kài

*dàs nài => dà

*kyùs nài => kyù

*sàin nài => sài

..

There are two adjectives associated with these question word / particle pairs. laubo meaning "enough" and kaibo meaning "suitable".

Also there are two nouns associated with these question word / particle pairs. lauja meaning "level" and kaija meaning "species/model".

sài

..

sài = because of

dari solbe sài ò = I started to drink because of her .................................................. sài ò can be considered an adverb of reason.

Note ... sài means "because of" ... sài gò means "because"

..

..

To say something like "john is as good at writing as jane" you have to use ʔà (or ʔàbis) ... see the next section.

..

Note that 3) and 8) do not mean the same thing ... kài defines a multi-characteristic concept (thing or action) while làu specifies position* on a uni-characteristic scale. [* or "degree" or "amount"]. So làu introduces only a quantity and kài intruduces a quality or manner.

..

..

I find the above table interesting. It is skewed ... OK pí wé nài ("in the manner that") can be used but it hardly ever is. Usually kài = "in the manner that". Why is it skewed ? My answer is ...

"For everyone the most important things around them are other people. And the most important "attribute" of a person is "how" they behave."

Hence kài has supplanted pí wé nài.

Also notice that any adjective outwith a NP has to be introduced by the copula, hence sàu kài instead of simply kài.

..

Note ... nù r làu jutu saduwo and nù r jutu kài sadu do not mean the same thing ... nù r làu jutu saduwo would be said when you have one specific sadu "elephant" in mind.

So nù r làu jutu saduwo => "they're as big as the elephant" ... nù r jutu kài sadu would be said when you are talking about elephants in general. So => "they're as big as elephants"

..

Good, Better, Best

..

làu is part of a larger paradigm ... the comparative paradigm ... demonstrating with the help of bòi ("good") ...

..

| >>> | boimo | best |

| > | boige | better |

| = | làu bòi | as good |

| < | boizo | less good |

| <<< | boizmo | least good |

..

The top and the bottom items are the superlative degree and so have no "standard of comparison".

The fourth one down is used less frequently than the second one down. This is because its sentiment is sometimes expressed by negating the third one down. For example ...

gì bù r làu bòi pawo = "you're not as good as me" can be used instead of gì r boizo pawo "you are less good than me"

[ actually gì r boizo pawo would be the normal way to express this sentiment. But gì bù r làu bòi pawo would be used, for example, as a retort to "I'm as good as you" ]

The superlative forms are found as nouns more often than as adjectives. That is boimo and boizmo are rarer than boimos and boizmos. (see table below)

..

boimos = the best : bàu boimo = the best man

boizmos = the least good : bàu boizmo = the least good man

..

[ you are argumentative like John but you are even worse ] ... explain this more

... ?ài

..

The same or not the same

..

ʔài = "same"

bù ʔài = "different"

Note ... for "the other", NP before the verb : for "another", NP after the verb)

1a) jono lé jene sùr ʔài bèn = "John and Jane are the same" ... logically the bèn is unnecessary, but it is often included ... euphony.

1b) jono r ʔài jenewo = "John is the same as Jane"

The above two examples are ambiguous as to whether John and Jane are the same w.r.t. one characteristic or the same w.r.t. all characteristic.

2a) jono lé jene r ʔài jutuwo = "John and Jane are the same size"

2b) *jono r ʔài jenewo jutuwo = "John is the same as Jane, sizewise" = "John is the same size as Jane"

The above is not allowed ... there is a rule saying that you can't have two consecutive -wo endings. So 2b) has to be re-assembled as ...

jono r làu jutu jenewo .... see Ch2.11.1

[Note jutuwo is derived from jutumiwo but the mi "ness" is invariably dropped.

ʔàibis = similar

ʔài dù = exactly the same

ʔaimai = similarity

lomai = difference

To say something like "John is as good at writing as Jane" we can not say *jono r làu bòi jenewo kludauwo [ ??? ] [ two consecutive -wo no good ? ]

You must use a sort of topic comment construction.

wo kludau bòi_jene r ʔài jonowo or wo kludau bòi_jene lé jono r ʔài

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences