Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

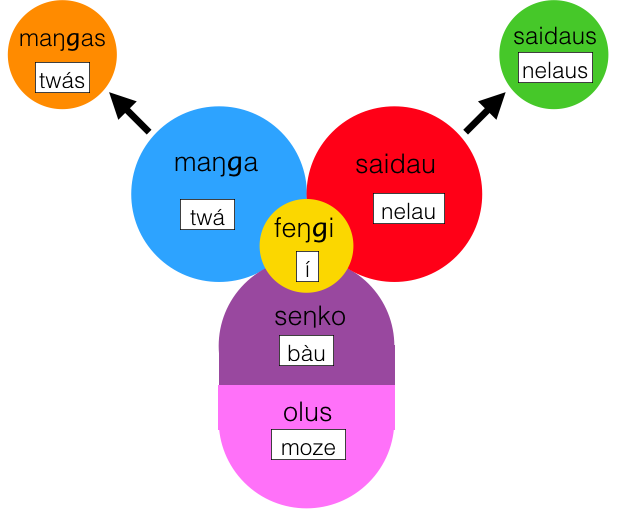

..... The 7 types of word

..

All words belong to one of the following 7 categories ...

..

1) feŋgi = particle ... this is a sort of "hold-all" category for all words (and affixes) that don't neatly fit into the other categories. Interjections, numbers, pronouns, conjunctions, determiners and certain words that would be classed as adverbs in English, are all classed as feŋgi.

An example is Í .. the preposition indicating the dative.

..

..

2) seŋko = object

An example is bàu ... "a man"

..

3) olus = material, stuff

An example is moze ... "water"

..

4) saidau = adjective

An example is nelau ... "dark blue"

..

5) maŋga ... It is the basic form of the verb. Not considered or a noun or a verb (however the verbs built up from it by adding suffixes ARE considered full verbs.

An example is twá ... "to meet" or "meeting" (That is the concept of "meet" disassociated from arguments, tense, aspect or whatever).

..

6) maŋgas = Not considered or a noun or a verb (although more of a noun than a maŋga). Derived from a maŋga by suffixing -s. The maŋgas means one instance of the activity denoted by the maŋga. For example ...

twás = "a\the meeting"

..

7) saidaus = a noun derived from an adjective. A saidaus is derived from a saidau just by suffixing an -s. The saidaus means one object possessing the property denoted by the saidau.

An example is nelaus = a/the dark blue one ....... nò nelaus = a/the dark blue ones

..

..

The maŋgas and saidaus are transparently derived from the maŋga and saidau so there is no need to list them ... in a dictionary say. However they are important in the grammar of béu, particularly the maŋgas.

..

..... Saidaus

..

saidaus => noun OR noun phrase derived from a adjective.

saidaus baga => noun

saidaus kaza => noun phrase

saidaus kaza can have 8 possible elements.

These elements are exactly the same* as the ones detailed in the seŋko section below, except the third element is saidaus baga instead of seŋko baga.

Actually saidaus can be derived from "locatives" and "genitives" as well as from saidau. For example ...

pobomaus = the one on top of the mountain

yós jene = the one belonging to Jane

* Actually there is one small difference. sowe can be an adjective to a saidaus but not to a seŋko. sowe is an adjective intensifier ( i.e. "very). So ...

gèu = green, gèus = a/the green one, gèus sowe = a/the very green one,

..

..... Maŋgas

..

Note .... In English there are various means to derive a pure noun from a verb. For example ... "discover" + "y" => discovery ... "destroy" + "?tion" => destruction ... "run" + ∅ => a/the run

In béu there are no method for constructing pure nouns from verbs. However the maŋgas is close enough to a pure noun for MOST intents and purposes. Also it is 100% productive ... that is EVERY verb in béu has a maŋgas.

English is very untidy when it comes to verbal nouns. Consider ...

1) The killing of the president was an atrocious crime.

2) Killing the president was an atrocious crime.

You can see that one form "killing" is used in 2 different constructions. By the way ... "killing" in (1) is considered more noun-like.

..

maŋgas => verbal noun OR verbal noun phrase

maŋgas baga => verbal noun

maŋgas kaza =>verbal noun phrase

The order for building up maŋgas kaza is ...

1) ... a numerative

2) ... the maŋgas (mandatory)

3) ... a determiner (dí dè lò or nái) ... but actually these are quite uncommon elements in maŋgas kaza.

4) ... the A argument (if it exists) marked for the ergative.

5) ... the S or O argument next in its unmarked form (of course if you have an S arguments ... there was no A argument in step 2)

6) ... other clausal elements (for example time, adverb*, instrument, reason, purpose ) can be added now.

[ actually an emphatic particle can be put at the front of all this lot and a relative clause put at the end ... but these usages are so uncommon, that I decided not to list them ]

*If an adverb ending in -we finds itself up against the maŋgas, the -we affix will be dropped.

..

One pilana can be appended to maŋgas, and that is -pi.

The usuage is actually exactly the same as the English ... "while verbing"

..

..... Maŋga

..

This corresponds to what is called "infinitive" or "masDar" in other languages.

But in certain circumstances maŋga can be thought of as a noun. (Actually maŋgas has a better claim to nounhood ... after all it is discrete).

For instance they can be the S O or A argument in a clause. I guess that is their biggest claim to nounhood.

Another place they appear is as complements* of active verbs (live verbs). Two examples of this usage are given below ...

1) ... blèu = to hold ..... laila = to sing, singing ..... jenes blor laila bòi = Jane can sing well.

2) ... cùa = to depart ... timpa = to hit, hitting ... jonos cori timpa jene = John stopped hitting Jane

* Since all live transitive verbs in béu are capable of taking a noun complement (object), this usuage can not be said to make them appear any less noun-like, however restrictions/differences in the elements comprising maŋga baga compaired to seŋko baga plus there inability to take all the 17 pilana do make them appear less noun-like .... Actually I prefer not to talk about nouns, verbs and what have you but to stick to the 7 word types** which I have devised for béu. However out of pity for the reader (yes ... you) I quite often revisit the terminology of the Western Linguistic Tradition.

** Namely ... feŋgi seŋko olus saidau maŋga maŋgas and saidaus

..

maŋga => infinitive OR infinitive phrase

maŋga baga => infinitive

maŋga kaza => infinitive phrase

The order for building up maŋgas kaza is ...

1) ... the maŋga always comes first

2) ... the A* argument (if it exists) will immediately follow marked for the ergative.

3) ... the S* or O* argument next in its unmarked form (of course if you have an S arguments ... there was no A argument in step 2)

4) ... other clausal elements (for example dative object, time, adverb**, instrument, reason, purpose) can be added now.

*When talking about these arguments we are thinking as if the maŋga has been brought to life. And we have a verb in its r-form, n-form, i-form or u-form. Then the A O and S arguments would live up to their name. However the A O and S arguments we are talking about here are merely elements in a noun phrase (or infinitive phrase if you will), as opposed to arguments in a clause.

**If an adverb ending in -we finds itself up against the maŋga, the -we affix will be dropped.

..

Two pilana can be appended to maŋga ... these are -tu and -la

The -tu usuage is actually exactly the same as the English ... "by verbing"

The -la usuage produced an adjective meaning ... "verbing" at the moment of speach. As with all adjectives it can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu doikala = a/the walking man

bàu r doikala = a/the man is walking

Note ... bàu r doikala = bàu doikora ... exactly the same.

..

..... Saidau

..

The saidau has two uses in the béu. It can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu gèu = a/the green man

bàu r gèu = a/the man is green

..

..... Olus

..

The olus kaza has the same stucture as seŋko kaza (see the next section) except there are three additional elements ... elements (9), (10) and (11)

(9) is always làu a particle (10) is a "number" and (11) is the holder

ʔazwo pona làu hói hoŋko = two cups of hot milk

..

ʔazwo = milk

pona = hot

hói = two .......... (10)

hoŋko = cup ..... (11)

..

Note nouns denoting quality are olus through derived originally from saidau. For example ...

nelaumi = blueness (from nelau "dark blue") and geumai = greenness (from gèu "green")

..

..... Seŋko

..

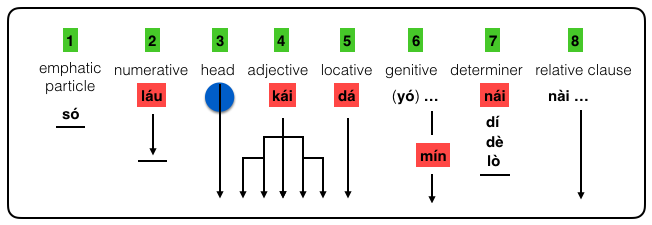

seŋko => noun OR noun phrase

seŋko baga => noun

seŋko kaza => noun phrase

seŋko can have upto 8 elements.

Below is shown the order in which they must occur.

..

..

Elements 1, 2, and 7 have restricted membership, if fact element 1 has only one possibility, the word hù. The words with red background convert the noun phrase (or indeed the sentence in which the NP is embedded) into a question. A blue circle indicates the only mandatory element. Branching arrows indicate multiple possibilities.

... The head

..

3) ... the head \ seŋko baga

..

... The adjective

..

4) ... the adjective

More than one adjective is allowed. For example ... bàu gèu tiji = the little green man

kái "what type" can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu kái = what kind of green man ? ... noun phrase question

bàu gèu kái glà timpori = what kind of green man hit the woman ? ... sentence question

..

... The locative

..

5) ... the locative. For example ... bàu gèu tiji pobomau = the little green man on top of the mountain

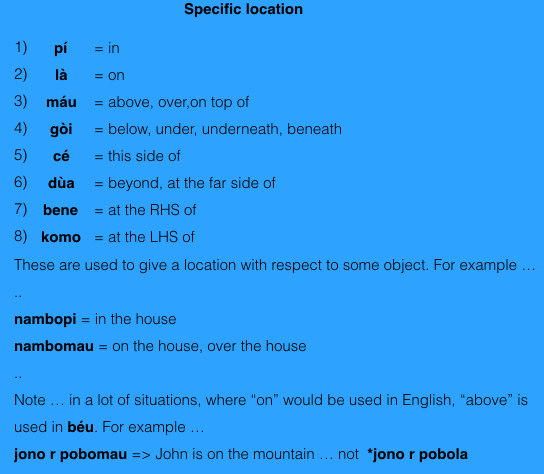

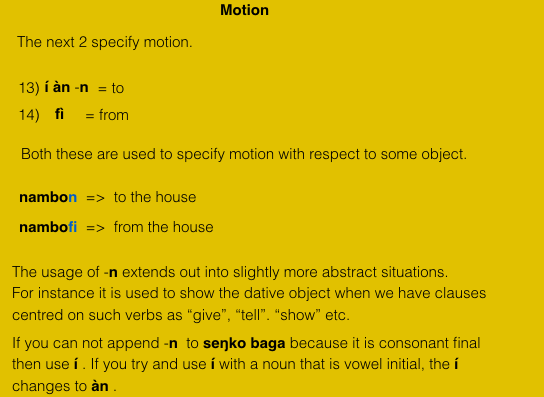

A locative comprises of a noun plus one of the nine affixes .... pi la mau goi ce dua bene komo ?e

The locative is a type of adjective.

Also a noun plus the affix fi can appear in this slot. This is not giving information about "location" but rather "origin". It is classed as a locative nevertheless.

Note ... if the noun taking the affix is a noun phrase ... well it is not possible to use the affix but you must use the stand alone term (see the section "the Case system" later on in this chapter). For example ...

to say "the little green man on top of the big mountain" => bàu gèu tiji máu pobo jutu

The above is called an ENP (extended noun phrase) ... it comprises bàu gèu tiji (NP 1) + máu + pobo jutu (NP 2)

Also dá "where" can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu dá = where is the green man ?

..

... The genitive

..

6) ... the genitive. For example jwado gèu nambomau yó jene = Jane's big green bird on top of the house

Note that the particle yó is usually dropped when the possessor is next to the head. However as other elements intervene, the likelihood that yó is used increases.

If mín (who) is used instead of jene in the above ... then we would have a question ...

jwado gèu nambomau yó mín = Whose big green bird on top of the house ? = Whose's the big green bird on top of the house ?

..

... The determiner

..

7) ... the determiner

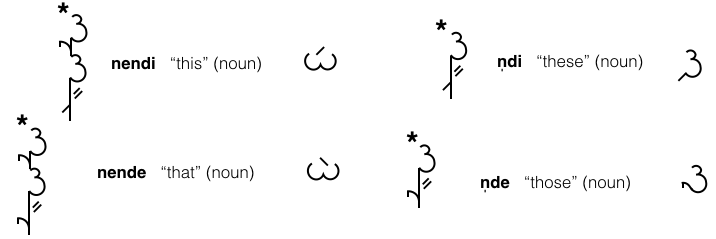

There are two determiners ... dí (this) and dè (that). For example ...

bàu gèu tiji pobomau dé = that little green man on top of the mountain.

The primary meaning is for comparing two objects that can be seen. Perhaps accompanied by gestures, dé will be appended to the further of the two objects and by way of distinction, dí will be appended to the nearer one.

nái (which) can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu tiji nái = which little green man ? ... noun phrase question

bàu gèu tiji nái glà timpori = which little green man hit the woman ? ... sentence question

Also lò "other" appear in this slot ... bàu gèu tiji lò = "the other little green man" or "another little green man"

Note ... dían => here, dèn => there ... not *dà dí and *dà dè

Note ... dí dè never appear independently as they do in English and many other languages. For example "this is good" => nèn dí r bòi .... literally "this THING is good"

Actually the above expression usually amalgamate to one word ... nendi r bòi "this is good" ... nende r bòi "that is good"

Note ... nò nendi is further contracted to => n̩di and nò nende => n̩de .... these are syllabic nasals ... the only two occurances of this sound in béu

..

..

Note that there is a short hand way to write these four words (shown on the RHS of the above diagram). Actually the long hand versions (shown on the LHS of the above diagram) are never used.

One little rule ... if a genitive is present, the determiners dí and dè can not be included. However dían "here" and dèn "there" can occur in the "locative" slot and we get the same meaning. If a genitive is absent, we do not get dían and dèn in the locative slot.

..

... The numerative

..

2) ... the numerative

These are ...

jù "no" ... ʔà "one" ... hói "two" ... léu "three" ... iyo "few" ... ega "four" oda "five" ..... hài "many" .... tautaita "172710 and ú "all"

The two "selectives" ... ín "any" and èn "some" go in this slot as well.

Only one word is allowed in the numerative slot (be it a selective or a numerative).

..

láu (how many) can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole sentence into a question. For example ...

láu bàu (r) pobomau = How many men (are) on top of the mountain ? .... *

With more complex seŋko baga it is usual to break it up in order to specify exactly which element is being questioned. For example ...

láu bàu gèu tiji pobomau nài doikura = " How many little green men on the mountain that are walking? " ... would be re-phrased as ...

wò bàu gèu tiji pobomau _ láu doikura = w.r.t. the little green man on top of the mountain, how many are walking ? ... or ...

wò bàu tiji pobomau nài doikura _ láu r gèu = w.r.t. the little man on top of the mountain who are walking, how many are green ?

Note ... in the 2 examples above, fì can be substituted for wò. However wò is more felicitous.

* Notice that in English and béu the copula can be dropped. In béu, when we drop the copula, what is left is analized as a NP (as opposed to a clause).

..

... The relative clause

..

8) ... the relative clause

Relative clauses "RC" work pretty much the same as English relative clauses. The relativizer is nài (that, who). Here are some examples ...

yiŋkai nài doikore = the girl that has walked

bàu nài glás timpore = the man whom the woman has hit

glá nàis bàu timpore = the woman who has hit the man

bàu nàin glás fyori yiŋkaiwo = the man to whom the woman told about the girl

glá naiji bàus bundore nambo = the woman for whom the man has built a house

All the pilana can be appended to the relativizer to specify what roll the noun would have in the relative clause if it was a simple clause.

..

... The emphatic particle

..

1) ... the emphatic particle is só.

só is used where we would use what is called "right dislocation" in English. For example ...

bàus só glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.

bàus só glán nori alha @ = Is it the woman to whom the man gave flowers ?

só might be used in exasperated when somebody can not see something. For example ...

| só nendi | "this one !" | só nende | "that one !" |

| só ndi | "these ones!" | só nde | "those ones !" |

This can also used as a sort of vocative case ... not obligatory but can be used before a persons name when trying to get their attention. For example ...

só jene = Hey, Jane

só gì = Hey, you

There is also an ajective intensifier sowe, which is no doubt related to the above.

..

..... Feŋgi

..

The feŋgi or particles are too diverse to say anything meaningful about them here. We will learn them one by one as we go though the ten chapters.

..

But just to fill out this section a bit, I will give you two sets of pronouns. One set being the pronouns in their unmarked form* and the other ... the pronouns in their ergative form**.

Here, for a transitive clause, "that which initiates the action" is called the A argument, and "that which is affected by the action" the O argument. Also, for an intransitive verb, the noun is called the S argument. It is convenient to make a distinction between all three cases. I follow RMW Dixon in using this terminology.

In most languages the S argument is marked the same way as the A argument. However in some languages the S argument is marked the same way as the O argument. These are called ergative languages. béu is one of these ergative languages. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative.

Below are the béu pronouns for the S and O arguments. This form can be considered the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | wìa | inclusive |

| us | yùa | exclusive | ||

| you | gì | you | jè | |

| him, her | ò | them | nù | |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

NOTE ... Pronouns differ from nouns in that their tones change between the ergative and the unmarked form. For a normal noun it is sufficient that -s is suffixed. For example ...

..

| bàu-s | glá | timp-o-r-yə |

|---|---|---|

| align=center|woman | hit-3SG-IND-PRF |

==> The man has hit the woman

| bàu | glá-s | timp-o-r-yə |

|---|---|---|

| man | woman-ERG | hit-3SG-IND-PRF |

==> The woman has hit the man

..

Below are the pronouns in the ergative form.

..

| I | pás | we | wías |

| we | yúas | ||

| you | gís | you | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

jè and jés are the second person plural forms.

There is one other pronoun ... the reflexive pronoun tí. This is always an O argument. Notice that it is the only O argument with a high tone.

* In the Western Linguistic Tradition, these "forms" are called "cases". The English word case used in this sense comes from the Latin casus, which is derived from the verb cadere, "to fall", from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱad-. The Latin word is a calque of the Greek πτῶσις, ptosis, "falling, fall". The sense is that all other cases are considered to have "fallen" away from the nominative (considered the unmarked form in Latin).

** By the way, there are 17 marked forms in béu ... the ergative being just one of these 17.

..

..... The case system

..

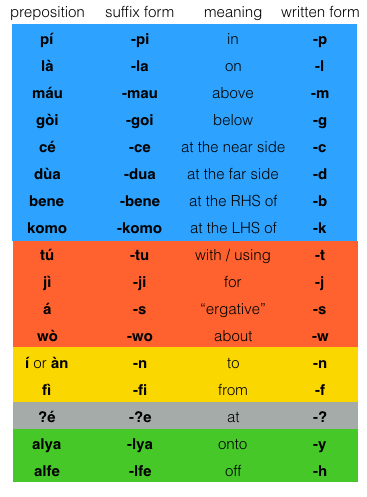

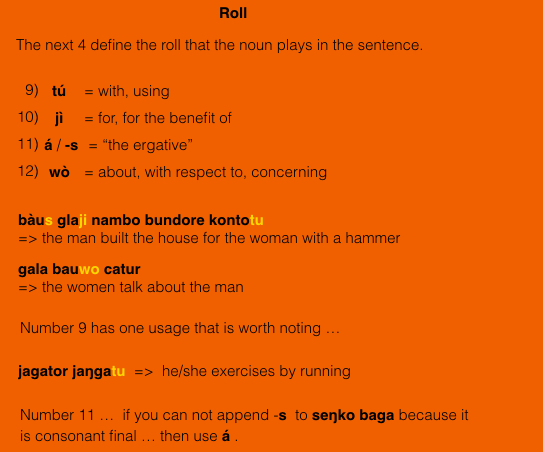

In total there are 17 cases (if you were to include the unmarked case as well the total would be 18). They are called the pilana.

These are attached to a noun and show the relationship of that noun with respect to the rest of the sentence.

..

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila (v) = to place, to position

pilana ( n) = the positioner

..

Probably the most important case is the ergative (the 11th case). In English it is the order of the verb and the arguments that shows who is the doer and what is the "done to". Namely the A and S argument come before the verb and the O argument after ... [ English is a non-ergative language and hence the A and S argument get treated in the same way.]

In béu, to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", the suffix -s is appended to the A argument. For example ...

..

glás bàu timporyə => The woman has hit the man ..... (with "the man" being the O argument)

glá bàus timporyə => The man has hit the woman ...... (with "the man" being the A argument)

bàu doikora => The man is walking ........................... (with "the man" being the S argument) ... [ béu is an ergative language and hence the O and S argument have the same form.]

..

..

The pilana are either realized as either affixes or as prepositions.

Whether the pilana appears as an suffix or a preposition depends on seŋko * ... if seŋko baga, then the affix is used ... if seŋko kaza, then the preposition is used. For example ...

nambodua = beyond the house

dùa nambo yó yinkai hauʔe = beyond the house of the pretty girl

* or in other words, if the NP is only one word one uses the suffix, and if the NP is more than one word one uses the preposition }

..

Note on the script ... If they are realized as affixes then, in the béu script uses a sort of shorthand. That is the affix is represented as one letter.

..

Earlier we have seen that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilana affixed to them. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilana then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

jonos jenes solbur moze = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of an affixed pilana, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lé should be placed between them. For example ...

jenes solbori moʒi lé ʔazwo = "Jane drank water and milk"

jonos jenes bwuri hói sadu lé léu ʔusʔa = John and Jane saw two elephants and three giraffes.

[ Compare the above two examples to á jono jene solbori moze = Jane's John drank water ... i.e. The John that is in a relationship with Jane, drank water ]

This word is that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

..

.. As parts of speech

..

pilana of location phrases (i.e. nouns with 1 -> 8 or 15) can be considered adjectives if they come after a noun and adverbs if they come after a verb. They must come after a noun or a verb. Sometimes they come after the copula*. In this case they are adjectives. Now often the copula is dropped ... but if this dropping results in any ambiguity it can be readily "undropped".

pilana of motional phrases (i.e. nouns with 13, 14, 16 or 17) can be considered adverbs. They can come in any position because it is understood that they are qualifying the verb.

pilana phrases defining sentence rolls (i.e. nouns with 9, 10, 11 or 12) can come anywhere. They are considered nouns.

* [ Notice that in English, you can either say ... "a bird is in the tree" or "in the tree is a bird"

In béu only jwado r ʔupaiʔe is valid ... also note that in this case jwado is not definite because it is left of the verb. That rule doesn't work with the copula. ]

..

... Questions

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 8 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "whose", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

[ Note ... there was also a "whom" until quite recently ]

These are the most profound words in the English language. (When I say "profound" I am talking about "time depth" ... these words are very very old)

However these question words have over the mellenia been sequestered to support other functions. For example "who" can be used to ....

1) Solicit a response in the form of a persons identity

2) As a relativizer particle ... for example ... "The man who kicked the dog"

3) As a complement clause particle ... for example ... "She asked who had kicked the dog"

4) In the compound "whoever" which is an indefinite pronoun.

Only in the first example is "who" asking a question.

..

béu is quite rich when it comes to question words. It has eleven ...

..

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| láu | "how much/many" |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| dá | where |

| nái | which |

| kyú | when |

| sái | "why"* |

| gó | "why"* |

| ʔai? | "solicits a yes/no response" |

| ʔala | which of two |

..

If you hear any of these words you know you are being solicited for some information. These words have no other function apart from asking questions.

..

Notice that there is no one word for "how" in the above table. This is expressed by the 2-word expression wé nái "which method".

On the other hand, béu has single words where English requires the 2-word expression "how much" and the 3-word expression "what kind of"

..

nós and mís are the ergative equivalents to nén and mín (the unmarked words). The dative forms are í nén and í mín.

..

English is among the 1/3 of world languages which fronts a question word. béu fronts 5 of its 11 question words ... nén mín sái gó and kyú.

Now láu kái dá and nái are stuck within** their NP (refer back to the diagram in the section titled seŋko) and the elements in a NP are fixed. Well it is possible that láu could come sentence initial but not kái dá and nái as they are positioned to the right of the mandatory head.

As for the other 2 question words ... ʔai? always come sentence final ... and ʔala comes between two elements of the same class (these elements subject to the usual ordering rules)

Here are some examples of these words in action ...

..

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 ... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 ... í mín bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 ... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... í glá nái bàus nori alha = the man gave the flowers to which woman ?

Question 5 ... á bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 6 ... alha kái bàus glán nori = what type of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 7 ... láu alha bàus glán nori = how many flowers did the man give the woman

Question 8 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔala cokolate = Did the man gave the woman flowers or chocolate ?

Question 9 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man gave the woman flowers ?

..

Occasionally you hear nenji instead of sái. This is just nén + the tenth pilana ... so it means "for what".

"how" is expressed as wé nái which means "which way" or "which manner"

* Let me explain why we have two "why"s. First I will digress a little. Nearly all the languages of the world have a question word directly equivalent to the English word "who". However languages having a plural of "who" are very very rare. The reason is not difficult to figure out. When you ask "who", you are asking about something that is unknown to you ... the plurality of that "something" is also unknown. (Not only would a singular-plural distinction for "who" be unnecessary ... it would be asocially awkward ... If in asking a question you picked the wrong plurality (i.e. "who".singular when the answer is plural or "who".plural when the answer is singular) the person answering would have to set you right ... would have to contradict you. OK ... in a similar way the word "why" could be split in two ... into "why".future and "why".past. "why".past would ask about a state or action that existed/happened previously and lead to a current state or action. "why".future would ask about a state or action desired in the future and the current state or action exists in order to bring about. Well the two "why"s are rare for exactly the same reason that the two "who"s are rare. But actually in some cases you DO know that it is a future state or action. sái is the normal word for "why", but in about 10 % of times you come across a gó "why".

** These 4 words often stand alone. But when they do, they are still considered within a NP ... only that the rest of the NP has been dropped.

..

... 6 generic nouns / 8 particles

..

| 1) | làu | as, so | làus | amount |

| 2) | kài | like, as | kàin | kind, sort, type |

| 3) | dà | where | dàn | place |

| 4) | kyù | when | kyùs | occasion, time |

| 5) | sài | because | sàin | reason, cause |

| 6) | gò | in order to | gòs | goal, aim, intention |

..

The RHS of the above table has six generic nouns. Not so much to say about them, but the related particles (shown on the LHS) are more interesting. The way these function is shown below ...

..

... làu / kài

..

làu means "to such an extent or degree" and is used in front of adjectives. For example ...

1) jono r làu bòi jenewo = "john is as good as jane"

1a) jono r làu bòi jenewo kludauwo = "john is as good at writing as jane"

2) Peter is làu fat_he plì not can walk

3) gì r làu gombuʒi jonowo = "you are argumentative like John"

..

kài means "in the manner or role specified" and is used in front a clause.

4) [ John smokes kài a chimney ] .... but notice that the clause has been reduced ... [ a chimney ] <= [ a chimney smokes ]

5) [ She will use deceit as before ] .... but notice that the clause has been reduced ... [ before ] <= [ she used deceit before ]

6) gì r gombuʒi kài jono = "you are argumentative like John" ... [ John ] <= [ John is argumentative ]

7) [ The kidnappers released him as agreed ] .... but notice that the clause has been reduced ... [ agreed ] <= [ all parties agreed ]

..

Note that 3) and 6) do not mean the same thing ... kài defines a multi-characteristic concept (thing or action) while làu specifies position* on a uni-characteristic scale. [* or "degree" or "amount"]. So làu introduces quantity and kài intruduces quality or manner.

..

..

I find the above table interesting. It is skewed ... OK pí wé nài ("in the manner that") can be used but it hardly ever is. Usually kài = "in the manner that". Why is it skewed ? My answer is ...

"For everyone the most important things around them are other people. And the most important "attribute" of a person is "how" they behave."

Hence kài has supplanted pí wé nài.

Also notice that any adjective outwith a NP has to be introduced by the copula, hence sàu kài instead of simply kài.

..

Note ... nù r làu jutu saduwo and nù r jutu kài sadu do not mean the same thing ... nù r làu jutu saduwo would be said when you have one specific sadu "elephant" in mind.

So nù r làu jutu saduwo => "they're as big as the elephant" ... nù r jutu kài sadu would be said when you are talking about elephants in general. So => "they're as big as elephants"

..

... comparing qualities

..

làu is part of a larger paradigm ... the comparative paradigm ... demonstrating with the help of bòi ("good") ...

..

| >>> | boimo | best |

| > | boige | better |

| = | làu bòi | as good |

| < | boizo | less good |

| <<< | boizmo | least good |

..

The top and the bottom items are the superlative degree and so have no "standard of comparison".

The fourth one down is used less frequently than the second one down. This is because its sentiment is sometimes expressed by negating the third one down. For example ...

gì bù r làu bòi pawo = "you're not as good as me" can be used instead of gì r boizo pawo "you are less good than me"

[ actually gì r boizo pawo would be the normal way to express this sentiment. But gì bù r làu bòi pawo would be used, for example, as a retort to "I'm as good as you" ]

The superlative forms are found as nouns more often than as adjectives. That is boimo and boizmo are rarer than boimos and boizmos. (see table below)

..

boimos = the best : bàu boimo = the best man

boizmos = the least good : bàu boizmo = the least good man

..

[ you are argumentative like John but you are even worse ] ... explain this more

..

... dà / kyù

..

3) dà = when (in its none interogative function). For example ...

pà twá dà yildos twairi = meet me where we met in the morning ................ ( dà yildos twairi ) can be considered an adverb (of place)

4) kyù = where (in its none interogative function). For example ...

toili gìn naru kyù twairu = I will give you the book when we meet ............. ( kyù twairu ) can be considered an adverb (of time)

kyù also means "if" ... the same as German.

..

... sài / gò / plì

..

5) sài = because. For example ...

toili òn nari sài ò klár = I gave her the book because I like her ..................... sài ò klár is a clause (specifying reason) ....................... has helgais

6) gò = "in order to". For example ...

pà dîan tare gò náu toili gìn = I come here to give you a book ...................... gò náu toili gìn is a clause (specifying purpose) ............ has manga

7) plì = then

Another particle that can be mentioned with sài and gò is plì. It too links clauses but has no connotations as to purpose or cause. It simple indicates that one action follows another.

..

... nài

..

In English, one of the functions of "who" is as a relativizer ... a particle that introduced a relative clause. For example ....

"The man who ate the chicken got sick"

Also in English, one of the functions of "that" is as a relativizer. For example ....

"The chicken that was eaten must have been off"

..

In béu there is only one relativizer, which is nài.

nài takes case affixes the same way that a normal noun would. For example ...

pi ... the basket naipi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

la ... the chair naila you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

... mau / goi / ce / dua / bene / komo ...

tu ... báu naitu ò is going to market is her husband = the man with which she is going to town is her husband ... kli.o naitu he severed the branch is rusty

ji ... The old woman naiji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

-s ... báu nàis timpori glá_sòr ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

wo ... The boy naiwo they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

-n ... the woman nàin I told the secret, took it to her grave.

fi ... the town naifi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

?e ... nambo naiʔe she lives is the biggest in town = the house in which she lives is the biggest in town

-lya ... the boat nailya she has just entered is unsound

-lfe ... the lilly pad nailfe the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

..

The relativizer nài always follows a noun. However there are two generic nouns that are never qualified by a relative clause. These are nèn and mìn.

Instead the three pronouns ò, nù and ʃì are used to form relative clauses.

*nèn nài => ʃì nài : *nós nài => ʃís nài

*mìn nài => ò nài : *mís nài => ós nài

*mìn nài => nù nài : *mís nài => nús nài

In English we have what is called a headless relative clause. béu does not have this. An English headless relative clause would be translated using one of the six forms above. For example ...

ʃì nài bwír sòr ʃì nài mìr = "what you see is what you get"

..

dàn, kyùs, làus, kàin, sàin and gòsi rarely take a relative clause.

..

dàn nài => dà

kyùs nài => kyù

làus nài => làu

kàin nài => kài

sàin nài => sài

gòs nài => gò

..

There is no rule banning the terms on the LHS, but they invariably are expressed as the RHS particle.

..

..

nài by itself is used to qualify a situation rather than a noun.

For example "John hit a woman, which is bad" would be rendered jonos timpori glá_nài r kéu

Note that there is a pause between jene and nài. If there was not this gap, the sentence would mean "John hit the woman who is bad"

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences