Early history of Paba

Early settlement

Bābā (hereafter Paba) was founded in 633 AD by immigrants from Laba. Though later famous for being the most pacifistic people in the world, the early Pabaps were just like their neighbors. They landed and estabslihed a new settlement on a bay in the south coast called Tamusur, meaning "by steps", as they planned to grow their settlement slowly but steadily from its base. Here, they grew rapidly northwards, killing any aboriginals they met who refused to convert to the Yiibam religion and lay down their weapons. Some aboriginals tried to escape into the cold interior, but this was not often successful because the interior was already populated by Repilians, who had been their enemies for thousands of years, and were already taking kindly to the Pabaps who were doing that job that they had wanted to do for so long.[1]

Founding population

Paba was very ethnically diverse for its time. Near the peak of its power, only 15% of the population was ethnic Pabaps. Note that ethnicity and religion were mostly synonymous, so the concept of mixed ethnicity for the most part didn't exist. The only exceptions were such examples like the Pabaps and Tarpabaps who both mostly believed in the Yiibam religion, but did not consider themselves to be the same ethnicity because they did not intermarry with each other.

Ethnic groups

The Pabaps had come from the highlands of Laba, in which people rarely traveled outside their home village because travel through the mountains was so difficult. Thus they had a highly diverse culture internally. However, despite being confined to the mountains, they actually had an advantage in getting out of Laba because they had access to rivers which emptied into ports along the East Coast of Laba that were further north than the port cities of their primary antagonists on Laba.

Thus Paba was from its very beginning sharply divided into two major racial groups: the majority Pabaps and the minority Tarpabaps.

The Tarpabaps lived the equatorial rainforests of southern Laba, and were all very tall, thin, very dark-skinned people. They had historically survived mostly by fishing, and had a well-developed navy, but their land was flooding much more quickly than most others because it was almost entirely coastal lowlands, and the few mountains they had were inconvenient places to seek refuge from rising tides.

The Pabaps had some coastland, but mostly lived in the temperate mountains. They were quite short people, ranging from chest-high to belly-high against the Tarpabaps. They had pale pink skin, blonde hair, blue eyes, and distinct facial features. The size difference between the two races was so great that both groups agreed to a cultural taboo against forming mixed families. This held true even when they came to share the same religion, Yiibam.

When an asteroid hit Laba, every society was ruined. Seeking a way out, the Tarpabaps gave the Pabaps access to their many ships in return for Pabaps guaranteeing them safe passage along the northern coast of Laba so that the two groups could both leave Laba and settle a new nation on the continent of Rilola. Thus, both groups came to Rilola in far greater numbers than one would have expected, and in fact formed many nations instead of just one.

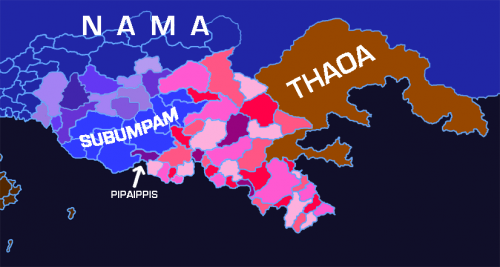

Once on Rilola, the two groups mostly stayed together. The new nation of Paba was formed, bordering Subumpam to the west and Thaoa to the east. The Pabaps admired the Tarpabaps' large, healthy bodies, and figured they would be reliable soldiers in a war. The Tarpabaps admired the Pabaps' generosity, as all of the other settler nations nearby had ruled the Tarpabaps out of their settlements entirely. The ships kept coming, and the population of both groups increased rapidly. Pabaps remained a majority because the Tarpabap people were divided among their home nations in Laba, and only those who agreed to submit to the new plan was allowed to move to Paba. Other Tarpabap ships were permitted to use Paba's ports in Haswaraba, but not to move on from there to settle Paba.

The settlers quickly agreed that their society would be better off if the two groups switched places: Pabaps would mostly live along the coast and focus on fishing and trade, whereas the Tarpabaps would move inland and focus on agriculture and the military. Large body size was no advantage at sea, except when rowing was the only means of moving, and the Tarpabap people seemed to have huge appetites even for their body size, which put them at greater risk of starvation. On the other hand, the Pabaps did not want to go to war against people that could step on and crush the puny Pabap soldiers while Pabaps flailed helplessly at their enemies' leg armor. Thus, most ethnic Pabaps did not join the military, but most Tarpabap males did.

Thus, the Pabap-Tarpabap alliance dominated early settlement of the new continent of Rilola for 860 years. Pabaps and Tarpabaps lived peacefully in Paba and the Tarpabaps mostly adopted the Yiibam religion from the more numerous Pabaps. Nevertheless, they still did not marry Pabaps. They did not disciminate based on skin color, but the very few children that were born from mixed marriages (generally involving a healthy Pabap marrying a Tarpabap who was malnourished or otherwise shorter than normal) were easily identified by their intermediate skin and hair color, and excluded from mainstream society. These people were called Sunflowers because they mostly had dark skin and blonde hair, at least by the definitions of those terms that Pabaps used. Sunflowers mostly married other Sunflowers, but their numbers never grew significantly. Note that unlike other empires such as Subumpam, in Paba there was no "bridge" population that was physically intermediate between the tiny Pabaps and the tall Tarpabaps. THe Pabaps had massacred the dark-skinned aboriginal Sukuna people, save those few that converted to Yiibam, and those few that did remain still did not marry Tarpabaps because to them, body type was more important than skin color, and that although they were taller than Pabaps they were still much smaller than Tarpabaps. (Note though that despite the huge difference in body types, Tarpabaps and Pabaps were more closely related to each other than to aboriginals such as the Sukuna, who had been living separately for tens of thousands of years.)

The War of 634

The Pabaps settled many cities along the south coast of Rilola, the most important of which was Tamusur Bay (usually just called Tamusur). This was a deep bay with an abundant fish population. They found that Tamusur was already occupied by the hostile aboriginal Sukuna people, who also lived primarily on fish and were not willing to let the Pabaps move in. The other early settlements were also preoccupied by Sukuna, but at a low enough population density that neither group saw the other as a threat, and did not even meet each other much. Other names for the Sukuna people native to the area around Tamusur were Astyzzians, Gê, Asetudi, Ahetùgi, Ahekuqhi, Ăheḳuki, Ahikui, Askʷ, Pasti, Basti, and Baste. All of these are actually different cognates of the same word.

The Sukuna were a very dark-skinned people, and the Pabap fishermen worried that they would be in trouble as their nation depended on the alliance of the tall dark-skinned Tarpabap people and the small light-skinned Pabap people. Pabaps worried that if the Tarpabaps chose to sympathize with the Sukuna solely based on skin color, Pabaps would be doomed.

Attempts at peace

Some Pabaps tried to make peace, but communication by human language was impossible, as the Sukuna were divided by language even amongst themselves and all of these languages had diverged more than 40000 years ago from that which was spoken by the Pabaps and Tarpabaps.[2] The Pabap sailors had founded their new settlement without bringing any weapons, as they had not needed them before in earlier settlements along the coast or on Fox Island. They thus figured the surprisingly hostile aborigines present in Tamusur must indicate that Tamusur was of special importance to the Sukuna people, being perhaps their capital city, and that its capture would enable the Pabaps to settle the surrounding areas more easily.

As above, the Pabaps did not have weapons, whereas the Sukuna were a heavily armed people using spears, swords, and arrows to defend themselves. However, they seemed to be materially starved, as they had no body armor, and in fact no clothes at all on their bodies. Pabaps did not have armor either, but figured that since it was much easier to manufacture weapons than to manufacture armor, they could quickly catch up and perhaps even exceed the Sukuna people in military power if their peoples came to war.

Moreover, the Pabaps did have emergency weapons such as fishing spears and wood axes at their disposal. Fishing in this age was almost entirely accomplished with shallow boats and sharp spears, so anyone who fished for a living needed to make sure his spears were in excellent condition. The spears worked best when their bearer was pushing strongly downward, but against a human enemy that didn't even wear clothes, any sharp-tipped weapon could be fatal. Thus the Pabap troop decided to attack the Sukuna living in Tamusur Bay, offering any Pabaps who didn't want to fight the opportunity to board a boat and sail to the east or west, both of which seemed to be much more peaceful despite being materially not greatly different than Tamusur.

Early on, the Pabaps and the Tarpabaps had agreed that since Tarpabaps were so much taller and stronger than Pabaps, they should be at the forefront of the army, with Pabaps restricted to less dangerous roles away from most of the combat. The Pabap leaders were thus upseet when the Tarpabap leaders told them they would not participate in any war against the Sukuna people, saying that they preferred peaceful cohabitation even if it meant that Paba would never control Tamusur. This left Paba the choice of backing down from their war plans after all, or going to war alone against the taller, better-armed, and likely far more numerous Sukuna people all around them.

They decided to choose war, as most of the Pabaps who had preferred peace had already left Tamusur to live along the outlying coastal areas to the east and west. Those people had founded the settlements of Poppempa (west) and Panta (east), meaning that these settlements were actually slightly older than Tamusur.

The Pabap military leadership figured that the Sukuna could not possibly consist of just a single nation running all across the southern coast of Rilola, or even just the area of that coast that had been colonized by Pabaps. Although they realized that communication with the Sukuna was hopeless, they held off on declaring war just so they could send peaceful diplomats to the areas around them to see if the Sukuna had any enemies that would be willing to help Paba in its war. They thus discovered Nama before most of the other groups did. However, the part of Nama that they reached was uninterested in them, and many of the Pabap diplomats had lost their lives while trying to communicate. The survivors returned to Tamusur and told the Pabap army to attack the Sukuna immediately, saying that all of the nations nearby seemed likely to be further enemies of Paba, and that if they delayed their war any longer they would simply be obliterated by a wider alliance.

Declaration of war

The first battle was fought in the summer of 634.[3] The Pabaps still did not have sturdy weapons, as they had no natural resources to build weapons other than wood, which was scarce, and they did not want to alarm their fellow colonists by asking them for weapons from Laba, knowing that all of the other colonies had so far expanded itself without the need to resort to a war. They took heart in the fact that the Sukuna living around Tamusur, despite being heavily armed, seemed technologically backward by comparison to the peoples they had observed in the aboriginal nations around them, suggesting that perhaps Tamusur was not the capital at all, but an impoverished, isolated settlement hated by even the other aboriginals.

The Tamusurian Pabaps had spent their first year mostly at sea. Since the Sukuna people would not let them set foot on Sukuna land, they had the choice of staying permanently offshore (there were some small islands that they could build forts on), or hiding out in thickly wooded areas just outside Tamusur that the Sukuna could not easily reach. Most chose the second option, and the Pabaps came to admire the protection that the dense forests around Tamusur gave them. Even the grass here was mostly much taller than a human height, and the Pabap settlements in the forest were thus literally invisible. Still, they needed to return to the sea frequently, since the forests in this area had been recently hunted to the point that fruits were the only available food for humans. The Sukuna's boats were essentially only good for fishing, and Paba realized that they could bump the Sukuna boats with their much larger cargo ships and thus destroy their way of life without having to kill any Sukuna, and thus without having to risk the lives of any Pabap soldiers.

Battle of Tamusur

The Pabaps realized that Tamusur Bay was an ideal shape for staging a naval blockade, only four miles wide for most of its length. Thus a blockade that could hold down the immediate coast could also hold down the entirety of the bay. The Battle of Tamusur began when Pabap cargo ships surrounded the Sukuna fishing boats and began pushing them back towards the beaches. Generally, any time a Sukuna boat hit the bumper of one of the ships, it was capsized immediately and the fishermen were usually pushed under the ship to drown. Thus the Battle of Tamusur began as no battle at all: it was simply Pabap sailors playing bumper cars with wholly unprepared enemies. The second stage of the battle occurred when the Sukuna who had survived rowed back to shore and alrted teh population of Tamusur what was happening.

The Pabaps had hoped the Sukuna people would surrender and let Paba take over Tamusur peacefully. But the Sukuna were unwilling to surrender, because they also knew that their forests had been stripped of their edible animal life, and that the sea was their only source of food. The Sukuna army marched out of their town and reached the beaches of Tamusur's southern coast, waving their arms at the distant Pabap ships in the hopes that they would hit the beach and be massacred by the Sukuna.

But although the Pabap sailors did bring weapons on board their ships, they were expecting the attack to come from inland. The SUkuna response of moving its army to the very edge of the shore had been unexpected, as it seemingly left the city of Tamusur itself entirely unprotected. They figured that some people in Tamusur would have weapons with them, perhaps for hunting, but they were pleased to see that their strategy of having the Pabap army roar down the hills around Tamusur and attack the Sukuna in their streets had suddenly gained an enormous advantage.

The Pabap army knew what was happening at sea even though they couldnt see it because they had previously communicated with the Pabap Navy on what day and at what time of day the events were going to happen. In early afternoon they thus marched out from under the flowers in their hilly hideouts and entered the city of Tamusur. They had expected the Tamusurian army to meet them perhaps halfway up the hill, but they saw no army at all before them, as the army had moved itself to the coastline expeecting the Pabaps to attack from there.

At first, the Pabaps were uncomfortable killing civilians. But they saw that the Tamusur civilians indeed did own weapons, and they were good ones for attacking humans. Thus the Pabaps did not consider their battle unfair at all, and lost many men in their battle. Moreover, they realized that the real Sukuna army would be after them before long.

The Sukuna population of Tamusur was about 22000, very large for its time. The Pabap colonists in and around Tamusur numbered only about 7000, but nearly the entire adult population among that 7000 had been militarized, as the pacifists had moved away and the Pabaps who fished the ocean depended on what had become the new Pabap Navy to get around.

The 4000 soldiers that entered Tamusur in the afternoon killed about 6500 Sukuna civilians, most of whom were women and children since the male population consisted almost entirely of fishermen or soldiers, both of whom were currently trapped on Tamusur Beach. The Pabap soldiers realized that even if they were later forced to retreat from Tamusur, the Sukuna nation of Tamusur was effectively dead, as it no longer had a significant female population to grow from. They knew that a few women were still hiding out in the city, but that they would be even weaker than those that had fought back, and would likely starve to death now that their food supply had been shut off. Meanwhile, the Pabap army set about occupying their city, and meeting up with the Pabap Navy just offshore.

The Pabap Army had two potential supply routes now: a difficult one back through the woodlands to their west, the site of the future settlement of Supi, and the direct route from the southern shore of the city of Tamusur to the Pabap Navy in its harbors. The only problem was that the Tamusur Sukuna army was still occupying that shore, still thinking that they were going to face an attack from the cargo ships.

Treaty of Tamusur

Most of the ordinary Pabap fishermen who had been expecting to be fighting a naval battle had slipped between the bumpers of the larger Pabap cargo ships now, and circled around to SUpi figuring they would soon be needed to deliver food to the Pabaps on the mainland if nothing else. This was only a distance of a few miles, and thus word of the unexpectedly easy conquest of downtown Tamusur had spread to the rump society of Pabaps (mostly women and children) still hiding out in the woods. These fishermen thus temporarily joined the army, figuring they would be needed for combat after all, but would be attacking from the north instead of the south. These people were all wearing blue and yellow clothes, which was significant because their presence in the city center would show the Sukuna that they were civilians.

The blue-and-yellow soldiers reached the southern shore of Tamusur, having killed only a few Sukuna people on their way down and losing none of their own. They were very well-armed now, as they had taken the few weapons that had been found in the city center as their own and did not generally have a problem wielding these new weapons. They brought a small number of captured Sukuna people with them, figuring that these would likely be the children and wives of the soldiers stationed at the beach. A few tied-up children were nailed to a wooden sign that the Pabaps had carried with them after they chopped it down. THey brought these children down to the beach as well, figuring that if the Sukuna soldiers saw their children being tortured by Pabaps they would be more likely to surrender without a fight.

However, the sight of the bleeding, crying children nailed to wooden boards and the Pabap soldiers kicking and slapping them to make their pain even worse told the Sukuna that Pabaps were unlikely to respect any surrender treaty. They realized that they had been outsmarted and were likely to lose their fight against the Pabaps, but figured that they had no purpose left in life but to do their best to avenge the murders of their wives and children. Acting as one, they made a desperate rush up the beach to meet the Pabap army. This was the third and final stage of the battle, and the only stage where Pabaps lost their men in proportionate numbers to the other side. But even so, there were only 5200 Sukuna soldiers on the beach, plus an additional 2000 fishermen who had been trapped on the beach with them, and they were mostly very hungry as their food supply had been destroyed. This against the new expanded army of 6000 Pabaps who were mostly better-armed was no fair fight. The Pabap army was willing to lose many bodies in this fight as they now considered victory to mean the death of the entire Sukuna population of Tamusur. Of the 6000 Pabaps, 3500 were dead by the time the last Sukuna resistor was finally killed.

The Pabaps declared their war over, having fought only one battle. They signed the Treaty of Tamusur with the other Pabap settlements around them, stating that Tamusur was now a Pabap city, and owned all of the land in the city of Tamusur plus all of the territory about 10 miles inland in all directions, except where previous Pabap settlements such as Poppempa had already expanded. The reason why they signed a treaty with other Pabaps instead of the Sukuna is because they still did not speak any Sukuna languages, and could not communicate to the Sukuna tribes living outside Tamusur what had happened. Sukuna people from other nations soon appeared at Tamusur's borders, confused as to where the people they'd expected to see had gone. Pabaps had to no way explain themselves, and did not even know if the surrounding Sukuna tribes would be angry, as they had still suspected all along that the Tamusurian Sukuna had been hostile to the other Sukuna, though perhaps not hostile enough that the other tribes would accept complete genocide and replacement by an alien people from across the ocean as an improvement.

Once the war was over, many of the Tarpabap people who had abandoned the Pabaps earlier moved back into Tamusur. The Treaty of Tamusur had forbidden them to move back, since they had refused to fight while thousands of Pabaps had died trying to secure the city, but the treaty did not prevent other Tarpabaps from moving in, and the "coward" Tarpabaps simply blended in with these. Likewise, some of the pacifistic Pabaps of Poppempa and Panta also moved into Tamusur.

Early outrech and trade

After the new nation of Paba had finalized its new borders, the Pabap royal family looked around for potential allies. Even though they had just destroyed the aboriginal Sukuna population of Tamusur, the Pabaps believed that their likeliest allies in their new homeland would be the aboriginals that still lived in the areas around them. They still held to their belief that Tamusur had been a nation and not merely a city within some other nation, and that it may have been a particularly aggressive one towards ints neighbors.

Tamusur was bordered by rivers on both the east and west; along the south coast, the two rivers almost run together.[4] They thus were in a good position to defend themselves from attacks if their plans to make peace with the surrounding aboriginals went bad.

The other aboriginal Sukuna nations were accustomed to trading with what had been Tamusur, and although fighting amongst the Sukuna was well known they were unfamiliar with the idea of total war and thus could not imagine that the Pabaps really had wiped out the entire preexisting nation. They thus did not greatly fear the Pabaps, and many Sukuna people moved into Paba and married Pabap women. Once in Paba they hurriedly created a pidgin language called Ŋititina that was mostly verbal but relied on more hand gestures than a typical human language and thus could not be written down. THere were actually two pidgin languages, one for the Sukuna who moved into Paba from the east and one for the Sukuna who moved into Paba from the west. However, settlement from the east soon dominated, even though the east side of the divide was poorer. The Ŋititina people imported a type of very sweet wine into Paba, and showed the Pabaps how to grow grapes. In return the Pabaps showed the Ŋititina and the other Sukuna people how to sew clothes.

Geography and early politics

For its entire history, Paba has been an absolute monarchy. In the latest era of its history, it submitted to the Poswob Empire, but the Poswobs allowed the internal government of Paba to remain a monarchy.

The Pabap royal family, Paptupa, has absolute power throughout the Pabap empire. They are often called White Pabaps, but this is not in reference to skin color, but rather the fact that they are the only people allowed to wear white clothes. They believe in the Yiibam religion, which worships gods that are physically present in Paba. There is one supreme god, Yīa, above all others, but this god is invisible and is often referred to as "the unknown". Yīa is noncorporeal and is often imagined to be purple in color as purple is the rarest color in nature. Purple is also associated with wine grapes, which form a large sector of Paba's economy, but the Pabaps do not carry the association so far as to associate Yīa with alcohol or even with grapes.

Political parties are forbidden. Although no nation on Teppala during Paba's peak power time was a democracy, Paba gave its citizens distinctly less freedom than most of the surrounding empires. Even hungry Thaoa, which prided itself on its people's ability to invade other countries (even Paba) without fear of a revenge invasion, allowed its people to form political parties which were allowed to hold opinions on controversial issues such as slavery.

Paba's ruling class did allow its citizens to stage political protests to make their opinions heard. For example, in 2060, the Pisimimbin people protested Paba's apparent lack of interest in the fates of the many Pabap teenagers being dragged off by Nama into the ungovernable tropical rainforests of southern Lobexon, never to be heard from again. The Paptupa family responded by reforming the system so that Paba would have greater control over which Pabaps were picked to go there, but did not stop the exportation itself as Paba knew it was overpupopulated.

However the Pisimimbin incident was a sign of a longstanding tradition of Paba's upper class having little interest in the welfare of its lower class, openly allowing foreign nations such as Thaoa to grab thousands of innocent Pabaps to work on plantations in Thaoa, so long as Paba's government was paid nicely for their complicity. Although the Paptupa were quite well off, and could afford to pour most of this money back into development of roads and industry in the towns the slaves had come from, the lower class of those towns still generally did not benefit from this and only during some eras were the families of the slaves compensated for their loss.

Of Paba's many neighbors, only Nama complained that Paba's absolute monarchy was unfair to its people. Thaoa did not mind that Paba was a monarchy because they believed that the monarchy was the very reason why Pabaps were so unreasonably submissive and even after generations living on plantations would never rebel against their Thaoan masters. Subumpam did not complain because although Subumpam was not a monarchy, its government was very strict, and felt that it needed to be in order to ensure that the 11 nations of Subumpam would stick together instead of trying to go their own separate ways. The Star Empire did not complain because, similarly to Thaoa, they believed that Paba's absolute monarchy was the only reason that Paba's people seemed to be unable to assert their interests, and therefore were easily captured as slaves. However, the Star Empire did not officially allow slavery; they merely tolerated the knowledge that in the tropical rainforests of its extreme south, there were many Pabap slaves toiling away under the watch of their Star masters, producing agricultural products that the Stars themselves found too painful to work for.

Like a trophoblast, Paba divided into many states as it grew, but remained united. They had traditionally had a high birth rate, and mostly avoided wars, which is why such a large empire grew from a small founder population. Unlike Subumpam to its west, Paba was really a single nation that divided itself into 41 states over the years rather than an alliance of historically alien cultures that merged together. This is why there was never a name such as "Pabap Union" and never any wars between the various states in Paba.

Note that the original Pabap state, Tamusur, is the small purple state in a deep bay along the south coast. Previously, the Haswarabic people of whom the Pabaps considered themselves a member had built many fishing settlements on the much larger and more obvious southeastern peninsula, but none of them had ever achieved strong population growth, nor did they seek political unification with each other, and so they only became part of Paba when Paba began aggressively expanding its empire towards the southeast and made peace with the people they met living there. This is not a contradiction of the above statement that Paba originated as a single nation because the small fishing nations of southeastern Paba had mixed origins and considered Haswaraba, rather than the Pabaps that were a subtribe of Haswaraba, their unifying nationality.

In the 1700s, two western Pabap states seceded from Paba and joined the Subumpamese Union instead.[5] Paba did not complain, because the Subumpamese Union was a multicultural empire where Pabaps were welcome and even dominant in some areas. From the 1700s to the mid-1900s there were 39 states in Paba. 25 of these were coastal states, and the other 14 all had waterways to the sea. Thus Paba was a very sea-focused nation even from its early beginnings.

Ethnic groups

Unlike most nations, Paba frequently imported people from Laba to live among its people. It could be argued that Paba was biethnic from its very beginning, since Pabaps had used Tarpabap sailing ships to reach their new homeland, and most Pabaps realized this, but since the original founding population was 95% Pabap and the ruling family was entirely 100% Pabap, and since the Pabaps and Tarpabaps did not intermarry, Paba is generally considered to be a Pabap nation that has many minorities inside it.

Note that in Paba, minorities are genuine ethnic minorities and not merely political or religious groups. This is in contrast to Nama and its holding territories, where two groups sharing the same culture and religion can form separate organizations based around politics. Indeed, Nama has always intended for all of its parties to be purely political, but because politics has always tended to coincide with religion, and religion with ethnicity, this ideal is rarely reached in practice.

Different groups had different statuses; they were not simply all treated as "minorities". The Andanese, for example, mostly prefer to identify themselves as simply a tribe of Pabaps rather than adopting an ethnic identity as they do in other nations. This is because they consider Paba their home nation. There are actually many Andanese tribes, each of which considers itself a subset of the Andanese, and considers the Andanese in turn a subset of the Pabaps, while considering all of Paba's other ethnic minorities to be completely separate from the Pabaps. Thus, the Andanese gain all of the privileges and all of the disadvantages of being Pabaps. Note that this applies only to Paba: Andanese living across the border in Thaoa and Subumpam identify themselves as Andanese, not Pabaps.

Besides the Pabaps and Tarpabaps mentioned above, Paba had many other ethnic groups:

Sukuna The Sukuna people in Paba had a more painful hiustory than their neighbors across the border in Subumpam. Paba had contained the easternmost Sukuna settlements, and these were very weak. The original Pabap settlers had not yet decided to become pacifists, and simply killed any Sukuna people they met who did not convert to Yiibam and lay down their weapons. They were able to do this because even the poor, desperate Pabaps immigrating into wholly unknown territory in the early 600's AD still had better weapons than the Sukuna, who had been cut off by mountains and sea for thousands of years. For the most part the Pabaps did not even need swords; they simply repurposed their fishing spears and wood axes as weapons since most Sukuna people were nudists who lacked even the ability to build themselves suits of armor.

Today the Sukuna have been mostly absorbed into the Pabap population and, like the Andanese, mostly identify as Pabaps. However separate social status is available for those Sukuna people who prefer to remain politically and religiously independent, and this offers its people both advantages and disadvantages.Nevertheless, the genity system encourages these people to marry out, even if it is to other Sukuna people who belong to the mainstream Pabap culture, so this population is dwindling.

Nik A settler people from the tropical rainforests of Laba who founded several colonies along the south coast of Rilola. Early on, their settlements were between Paba and Subumpam, particularly the Subumpamese city of Pipaippis. Like the Tarpabaps, they were very tall, dark-skinned people, and simply could not blend in amongst the waist-high Pabaps, nor even the taller but still very pale Subumpamese people to their west. Their culture was similar in many ways to that of Paba, in that they preferred to live along the coast and make a living mostly from catching and selling fish. They were disappointed when Paba began aggressively expanding its navy, however, and told the Nik leaders that they would no longer share their sea space with Nik fishing boats. Some Nik people moved to Subumpam and tried to blend in with Subumpamese people there, but most stayed in Paba and tolerated the new rules since they realized that they at least had a safe place to live and were still the owners of most of the coastal land in their home area which meant that they could still profit enormously from the fish trade even though their boats had been beached.

Like the Tarpabaps, the Nik had been a strongly violent culture in the past, and their cities had a high violent crime rate, but they considered it a far greater taboo to attack the helpless Pabap people than to attack each other. Thus the Nik, despite being a heavily armed people as fishing in this age was done mostly with spears, never seriously considered an attack on the strong Pabap navy to their south nor on the weak Pabap civilians to their north. As above, though, they still confidently ruled their home states of Waba, Pusa, and Pama,[6] and coerced the Pabaps that they deserved extra money from Paba's government to ameliorate their situation. Paba agreed, and monetary poverty among the Nik was abolished, as even the poorest Nik citizens now earned more money from Paba's government than the entire Pabap underclass and much of its middle class. Nevertheless, the high cost of food in their areas coupled with their larger appetites meant that this money was only enough to prevent starvation, rather than to actually eliminate poverty.

Some Nik people abandoned their way of life and moved into northern Pabap cities and took normal jobs among the Pabap peasantry. They adopted Yiibam and came to live a lifestyle much like the Tarpabap people. THis meant, however, that they were subject to military service, and although Paba avoided wars at extreme costs those few wars that did occur tended to kill far more Nik soldiers than Pabap soldiers, as the Nik were much better soldiers and were given front-line combat positions.

Unlike the Tarpabaps, the Pabaps created a separate genity (see below) for the Nik. This encouraged them to marry Tarpabaps and thus become Tarpabaps. Thus the population of Niks declined in every region except their original homlenad in southwestern Paba. In the southwest, by contrast, the Nik split into two groups so they could marry each other without worrying about accidental cousin marraiges. The two groups were the Orange and the Purple.

Fua are people living mostly in northern Paba who are disliked by all of their neighbors, even other marginal groups. They were called Pispitam by Pabaps, meaning "kings of cutting", because they seemed to cut open or otherwise destroy everything they touched. Fua was simply the Pabap transcription of their Khulls name, xʷugâ. Unlike other minorities, Fua people rarely identified themselves as such, since doing so only brought them disadvantages. It was not even clear to Pabaps whether the Fua were aboriginals or if they had come from Laba and reached Rilola even before the Pabaps had and then moved away from the coast. What was clear was that nobody considered the Pabaps to be racists for singling out the Fua as the target of their hatred; everyone else, including Paba's enemies, also hated the Fua if they had any Fua people living amongst them. The one exception to this rule was Nama, which did not bar any ethnicity from being welcome in Nama. This, combined with the fact that the Fua lived mostly in mountainouse areas, led many people in Paba, Thaoa, adn Subumpam to believe that the Fua had come to them from Nama. Most violent crime in northern Paba was committed by Fua people against Pabaps and Sukuna, and they make up 70% of the prison population historically. Although this is largely because sometimes non-Fua people would join the Fua for protection once convicted of a crime, making the Fua's per capita crime rate higher and that of the other groups much lower, in some cases zero. Also, although it didn't happen often, a Pabap attacking a Fua was often considered a revenge crime, since Fua had hurt the Pabaps so much, and because Paba considered its notoriously pacifistic people to be still too violent, which paradoxically meant that those few Pabaps who did commit violent crime were confused with Pabaps who were mentally ill and thus not punished (but were usually sent to do farm labor where they could not hurt anyone.)

Other, later names for the Fua living in Pabap territory included Pessitam, Mibassitam, Mibaptam, Paspetam, Vaspetam, Mibažvwob, and Pambuob.

Thaoans Few Thaoans moved to Paba. Thaoa's government philosophy despised the submissiveness of Paba's massive lower class, and Thaoa realized that its citizens, if they chose to move to Paba, would not be entitled to join the upper classes even if they had been the upper class in Paba. In Paba's later days, some Thaoans were invited in for the sole purpose of easing the transfer of underclass Pabaps to slave plantations in Thaoa. These people did not openly identify themselves as Thaoan, however, for fear of a public backlash.

Subethnic divsions

- See Pabap culture.

The Yiibam religion divided the people of Paba into genities, or moieties, called lisa. Each was assoaciated with a color name, and the people traditionally wore that color at least as underwear. Nudism was allowed, and provided a freedom from the constant association with one's genity. The genities, however, largely corresponded to ethnic groups in early Pabap society, and only became blended together much later.

Blue A group consisting of the navy and all people who work primarily at sea, whether they be fishermen, traders, or explorers. This is because all of these groups are dependent on Paba's strong navy for their existence and for the most part actually overlap with the navy. In much of Paba, especially far eastern Paba, the Blue people have a very close culture, with men spending days a time without seeing their wives. Note that Paba's genities are not ethnic groups because people are encouraged to marry outside their group. Thus, most Blue men do not have Blue wives, although the taboo is not strcitly enforced in the fishing-dominated areas of the east because the vast majority here is Blue and therefore the population would simply die out if they were forced to marry non-Blue people.

Purple The land army. The color is named after Paba's wine grapes, the source of much of its fame and wealth. They were early on the commonest choice for Orange people to marry, and thus the Orange people got a strong link into Paba's military. The military is purple becayse protecting Paba's vineyards is almost as important at protestcing its people. The Purple group also includes workers on the vineyards, but does not include other farmers such as those involved in growing large vegetables.

Red A term for the farming class. They generally live on hereditarily owned farms, but many of these farms are large enough that they can hire outside laborers. These laborers, however, maintain whatever their original color association was, and do not simply all become Red.

Yellow A term for people who live in large cities and mostly work manual labor jobs. However, schoolteachers are also Yellow. The term "Gold" is avoided because it is the name of a much larger and unrelated political organization based in Nama. Gold people in Paba are usually classified as Black.

Orange A group created for the Nik, a group originally found along the southwest coast, just west of the original Pabap settlement in Tamusur Bay. Many of them moved north into the core of Paba, but did not blend in because they were very tall and dark skinned and didnt feel comofrtable marrying the small, blonde Pabap people. However, they were discouraged from marrying other Orange people, because that could lead to accidental cousin marriages, so when they first moved north they oftne had a difficult time finding marriages.

Green A group consisting of the decendants of anyone who has violated hte marriage restrictions, or has married a foreigner. Orange-Orange marriages are not actually illegal, it just is that their children are put into the Green group instead of inheriting the ORange. Anyone marrying Green becomes Green themselves, as do their children.

White The ruling class, living mostly in and near castles in Paba's capital city of Biospum.[7] They generally do not marry any non-White people, but doing so is not forbidden. They do not have a problem with inbreeding because the Whites are the descendants of the entire founding population of Paba save for the ethnic minorities that came with them on their ships.

Black A group for foreigners outside the caste system. Not a synonym for Green becasuse anyone marrying a Black becomes Green, not Black. Thus Blacks can only have Green children.

Early relations with Nama

Pabaps moved into Nama during the period roughly 1400-1700 AD to work in mining. This was a painful, dangerous occupation, but it was highly profitable. Nama had been living for 18000 years in these mountains without realizing they could extract the metals. Paba thus gained an early advantage in war because they had access to metal both in Nama and in their own territory, and could build swords and shields out of iron where others had only wood. They did not attempt to take over Nama, however, and immigration into Nama soon stopped as Paba increasingly oriented itself towards the tropics.

Relations with Thaoa

Paba was blocked on its eastern border by the nation of Thaoa. Paba and Thaoa had similar cultures, but Thaoa had rejected the alliance with the Tarpabaps. Thus they had no Tarpabapsbut a lot more Andanese people.

Thaoa was happy to border Paba because the Pabaps were small, physically unthreatening, and easily captured into slavery. The Thaoans had plenty of other cultures around them, but they did not generally enslave those people because they felt intimidated by them. Early attempts at enslaving Repilians had led to revolts, whereas the Pabaps captured by a slavemaster would only smile and pretend their bleeding had stopped. Thaoans referred to the Pabaps variously as "Lenians" (from Lenia, their name for Paba plus the unorganized territory of Pupompom to the north), or as Pilipupu or Sipuipmi, which are words respectively from Andanese and early Pabappa. Lenia is a transscription of the early Thaoa word Laenlat, meaning "land of simple childlike people".

Illegal slave raids

But illegal slave raids were nonetheless dominated by Thaoa. Thaoan warlords abducted young Pabap children by force, figuring that child slaves would be even more submissive than adults.

The Marpa Wars

- The Dots

In 1470, a segment of the Thaoan army broke away and called itself the Dots. The Dots rode into the Pabap state of Marpa and claimed it as their own. They enslved the Pabap soldiers and instituted a form of slavery on the rest of the population that was more severe than that which existed in Thaoa itself. At first, they had hoped Thaoa would accept the Dots and their invasion as legitimate, and allow them to become the new Thaoans state of Marpa. But Thaoa rejected them, and also blockaded their border to prevent them from getting back into Thaoa. The Pabap military also blockaded the rest of Marpa's border (the Marpa-Thaoa border was much longer than Marpa's border with the rest of Paba). They were hoping that the Dots would starve when they were deprived of all trade and all access to the coast.

The Dots countered by saying that if they were about to starve, they would make sure the Pabap slaves got the worst of it and that the Dots would only starve once the rest of the population was dead. Pabaps pleaded for Thaoa to invade Marpa and then give the territory back to Paba, but Thaoa's military commanders said that if Thaoa was forced to occupy the territory, then they would keep it as part of Thaoa and not sign it back to Paba. The Pabaps responded that they shouldn't have to use their military because Thaoa was the one who had sent the occupying army in the first place and therefore Thaoa was the one who had caused the problem. Thaoa's government publicly told the Pabaps that while Paba's commitment to pacifism was an admirable trait, they could not suffer an invasion and expect another country to bail them out while the Pabap army sat idly by simply because they were pacifists. But privately, Thaoa hoped that Paba would agree to let Thaoa take over, but did not want to preeemptively invade as they knew that their army would suffer heavy casualties from the Dots.

The diplomatic crisis was not resolved until 1474. Paba's army invaded the territory of Marpa, suffering many deaths at the hands of the Dot soldiers and slavemasters. In return, Paba agreed to send Thaoa thousands of slaves, consisting of both the Dots and various Pabap people from within Marpa, and to send a few hundred more each year for free unless Thaoa decided to seek payment in some other form of currency. Both countries then strengthened the military force along their borders, particularly the difficult southern section of the borders where the national governments of both Paba and Thaoa were weak.

- The War of 1531

In 1531, relations between the two young empires were strained again. The sea level was rising, and Thaoa's land was nearly split in two at one point near their border with the Pabap state of Marpa. This was the same state that had been invaded for unrelated reasons sixty years earlier. Knowledge of Paba's pathetic performance in that war was still widely known, and Thaoa decided to stab them again in the exact same spot to try to fix the problem of sea level rise by giving themselves more land.

Again the Pabap commanders responded to the invasion by pleading with Thaoa to pull their army out, and promised generous concessions such as allowing Thaoa to build roads through Pabap territory if they would only agree to leave the borders alone and let the Pabap people live painlessly. Thaoa made a counter-offer: if Paba agreed to let Thaoa take over Marpa, Thaoa would agree to enslave the Pabaps living there instead of killing them. Reluctantly, Paba signed a treaty turning over Marpa to Thaoan control, but prepared for a war in private as many families had been split by the border (Thaoa had only occupied the more densely populated eastern part of Marpa) and Thaoa refused to reunite them unless the free side of the family agreed to be also enslaved.

Through trading with Nama, Paba had acquired weapons superior to those of Thaoa for the first time. Even though Pabap soldiers were reluctant to hurt people, the screams of tortured Pabap slaves they heard as they reentered the towns they once knew motivated them to strike mercilessly at the Thaoan army holding Marpa's people captive. Thaoa was surprised by the sudden change from total passivity to all-out war, and realized that perhaps Paba's military no longer considered it wise for its soldiers to meet their enemies' swords and spears with flowers and feather pillows. Thaoa no longer even had a sizable force in, figuring that since Paba hadn't attacked their encampments for more than two years (this was 1533), that they never would.

Thus THaoa surrendered and the land was returned to Paba in the Treaty of 1533. Paba considered going even further, attempting to occupy the coast and therefore break Thaoa in half once and for all, as they felt that such a move would show Thaoa that Paba was no longer a nation of sissies who responded to every violent invasion by inviting the invaders even further inside. But Thaoa itself was guarded by an army many times stronger than the small force which had been keeping watch over Marpa, and Paba was not prepared to juice thousands of Pabap bodies into blood in a quest simply to push their borders a few miles further east. Thus the treaty called for a total cessation of war on both sides, and put in place a system of checks and balances to make sure the two empires would not at any time in the future ever declare war on one another.

Back home in Thaoa, the military decided that if Thaoa needed to grow, it should stop worrying about building slave plantations in states like Marpa and instead move along the coast. Paba was already doing that, and doing it quite well. Fishing was now producing more wealth and sustenance for Paba than land-based agriculture, even with Paba's huge land area, and as sailing technology improved so could the distance out to sea that each fishing boat could travel. Thaoa preferred to expand aggressively eastwards, into territory populated by weak, war-naive Repilian tribes. These societies were mostly led by women and did not have up-to-date technology either in their military or in their civilian society. THus, the Thaoans were able to make a legitimate argument that they were actually helping the Repilians, even though they demanded military control of their nations. They offered to teach Repilians how to build boats and how to sail deep out to sea without worrying about being stranded. But they did not offer to suit and arm Repilians as soldiers in their army, either male or female.

Paba's government held a massive celebration of the new peace treaty in central Paba, inviting Thaoan government officials and ordinary citizens of Thaoan ancestry living in Paba to attend and make new friends. Note that at this time the official languages of the two empires were still mutually intelligible, and that the linguistic differences were in fact the result of many uneducated Pabaps from the north still speaking their ancestral Haswarabic languages.

- War of 1539

In 1539, Thaoa invaded the Pabap state of Nansa Wipambim. They had sent many spies to the Pabap Peace Party in 1533, eagerly learning what Paba's greatest military weakness was. They realized that Paba had only "won" two wars against Thaoa recently by pushing the small Thaoan occupying force out of Paba's land, taking many casualties as they did so. But the Pabap army in both cases had stopped when they found themselves faced with the actual Thaoan army, which was much larger. Thaoa readily admitted that they had fallen behind in military technology and that Paba might actually be stronger than Thaoa overall. But the Pabap army was extremely passive, and Thaoa figured that even if they declared war and "lost" yet again, the Pabap army would be afraid to chase the Thaoans any further than their pre-existing border and therefore even in the worst possible scenario the Thaoans would come out of the war as if they had never fought it at all. Thaoa did not consider either of the two recent wars to have been Pabap victories, as all they had won was to get the Thaoan army out of Paba, in essence to get Thaoa to treat Paba as an equal.

Put another way, Thaoa now believed it could do essentially anything it wanted in Paba and Paba would never retaliate by attacking Thaoa; they considered removing the Thaoan invaders to be the most aggression they were capable of. Thus they invaded southern Paba in 1539 attempting to cut their way down to the coast and divide Paba into two, in much way Thaoa had been worried THaoa itself was going to be soon divided by rising seas. They chose Nansa Wipambim because it was an almost landlocked state, yet it contained all of the major roads connecting Paba's southeastern fishing-oriented states to the rest of Paba. Thus Paba could not fight the invasion by simply encircling Nansa with the Pabap navy; all this would do would be to hurt the states around it. Thaoa's invasion was thus entirely a land-based one.

Thaoa was delighted at Paba's reaction to the war. Paba's ambassador to Thaoa visited the embassy sobbing and pleading for Thaoa to stop the invasion and leave Paba alone. She promised major concessions for THaoa if they agreed, including the ability to set up slave plantations unopposed inside Paba's territory, and the right to hold posts in Paba's government, so long as the military was sent home.

Since Thaoa had invaded Paba only six years after they had signed a peace treaty swearing they would never again fight a war, Thaoa's government realized that they had scored a major diplomatic victory. From now on, they said, they would grow their territory by invading Paba and biting off important pieces of land, and then signing a peace treaty in which Thaoa was given extra money and slaves from Paba in return for promising to never take more of Paba's land. Then they would wait a few years to build up their armies, and then violate the new peace treaty in the most destructive possible way. They would repeat this process until they had cut Paba into tiny discontiguous patches of land which would each become large slave plantations for the Thaoans to rule over.

However, Thaoa's border with Nansa was much smaller than its border with Marpa had been, and they could send only a relatively small occupying force. Even as they realized the war might have been a bad idea, they were confident that Paba would not invade Thaoa because the same short border would slow them down if they invaded from Nansa, and the strong Thaoan army would stop them if they tried a surprise revenge attack anywhere else.

Organized slavery

Although Paba was militarily powerful, and could easily have burst into Thaoan territory and freed its slaves, and even made slaves of the Thaoans, they never did so, because Thaoa was also powerful and the Pabaps wanted to remain friendly. Pabap governors rarely interacted with the Pabap underclass, and saw the slavery program as a way to solve Paba's overpopulation problem, while at the same time satisfying the demands of Thaoa's farmers who seemed to produce much more food than the warmer but somehow less productive wage-labor farmers in Paba.

Indeed, Paba accepted slavery to such an extent that it paid money to support Thaoan slavemasters who wanted to move to Paba permanently and run their slave trade from the inside. They still were not legalizing slavery in Paba, merely taking the burden off of the states that were immediately adjacent to Thaoa.

In the early days of their cooperation, Thaoa had taken slaves primarily from the Pabap states of Nappi,[8] Marpa, Pispa, Munsar, and Nansa Wipambim. These were not the only states that bordered Thaoa, but they were the ones that bordered Thaoa's choicest farmland.

The typical early Thaoan slave gathering was very organized. The Thaoans would tell Paba's government which city they wanted to raid, and the governors of the state would organize a community frstival in that city in an attempt to get as many people as possible out of their homes. They would also be very well fed. Then towards the end of the festival, the people would disocver that the Thaoan army had surrounded their festival, and they could not leave the city center. Then the Thaoan soliders would march into the gathering of people, picking out the ones they wanted to a number previously agreed upon by the governments of both nations. They preferred to take teenagers, since they would be the healthiest and most reproductively successful. Moreover they were unlikely to have children and most Pabap teenagers had moved out of their parents' homes. They would tie up each new slave and put them in a crate that was then towed to Thaoa by very aggressive horses.

The population of these states was upset by the slavery problem, but felt powerless to stop it. Typically during the height of the slave raid the mayor and other important officials of the city would be perched on top of a tall building overlooking the city center, thus preventing them from being mistaken for potential slaves and also from being targeted as the source of the slavery problem by the peasants that were being picked and sorted. After the raid was over the officials would apologize for the disruption and claim that because the slave raid had been sponsored by the Thaoan army, only Paba's army could get them back, and Paba did not want to fight a war.

Typically each raid would take away about 20% of the teenagers of the city, which led to decreased population growth and increased poverty since the most capable people had been taken away from them. Thus even pro-slavery Pabaps were upset that slavery was hurting their economy even though the money paid to the government really did generally go towards improving the lives of the people who had been spared from the slave grabbers.

Thaoa was not entirely happy with their setup, either. The community festival trap method was successful at getting them a huge number of slaves with relatively little effort, but since Thaoa wanted slaves msotly to work on farms, and farmers were generally uninterested in moving to cities, farm-ripe teenagers rarely reached the hands of the THaoan slavelords. However, Paba was strong about keeping its farm population protected, whether they l;ived on family farms that had been handed dwon for hundred of years or gov't-run farms where people worked for money. Thaoa sometimes resorted to illegal slave gathering in which Paba would not be paid.

Slavery reforms

Paba did not think itself weak for allowing other nations to enslave them. They said "we farm with hoes and plows, others farm with whips and candles, and we both do well." To solve their disagreements with Thaoa, Paba in the 1600s began paying Thaoans seeking slaves to infiltrate the rest of Paba and extract slaves from the general population instead of holding surprise parties near the eastern border. They wanted Thaoans everywhere to share the burden equally amongst all the Pabaps. Paba considered these Thaoans to be part of the municipal gov't of each city, and therefore granted them a salary and full police protection. To prevent outagre, these people would claim to be Subumpamese instead of Thaoan. Cities that had these people educated their children on the basics of farm labor, saving the THaoans the trouble. Pabaps who found themselves in debt were then sold into slavery rather than imprisoned. If they had children, the children were taken with them. Soon, many Pabap cities created special taxes that applied only to the poor, as they wanted to make it harder for the underclass to escape being sold into slavery. This ensured a reliable supply of farm workers for THaoa.

Thus, the new slavery reform had accomplished five key objectives that Paba wanted:

- It moved the focus of the Thaoan slave drives from the already struggling inland east areas of Paba towards nearly the entire territory of Paba, and reduced the disproportionate strain on areas that were infected.

- It took away the frightening "surprise party" method of gathering slaves in which the police in each city were forced to collaborate with the slavelords, and then go back to their jobs as if nothing had happened.

- It allowed Paba to solve its persistent overpopulation problem. Paba had always had a high birth rate and a low death rate, due to the relative lack of disease, famine, and war in Paba.

- It removed the need for the aggressive Thaoan land army to be present on Pabap territory. The Pabaps they abducted were unarmed, but often fought ferociously against the Thaoan soldiers, who typically needed 3 Thaoans for each Pabap. One soldier would grab the arms, another the feet, and a third soldier would march directly behind them typically with a spear sticking under the hapless slave's clothes.

- It ensured that the people being enslaved were now largely chosen by Paba instead of by Thaoa. Paba had always disliked the old method wherein a crowd of Pabaps was suddenly attacked and the Thaoans chose whoever they wanted, with no apparent way to judge them other than their physical appearance. Under the new system, Paba was spilling its waste population all over Thaoa, and Thaoa realized this, but did not object so long as violent criminals were still excluded.

Thaoa had typically preferred female slaves, even though they were less capable of performing the difficult labor associated with temperate agriculture. Paba however even under the old system would not allow the Thaoans to simply grab every teenage girl off the streets and cart them away back to Thaoa. But now under the new system most of the people being enslaved were men, because men tended to be the ones to go into debt. Paba knew that this helped them, because Thaoans were entitled to all of the children of their slaves, which meant that if Paba exported mostly men, Thaoa would need to keep coming back again and again to get more slaves, whereas if they had a large female surplus in each new generation, the slave trade could entirely stop before long. Thaoa realized this as well, and pressured Paba thus to create another system that would tip the enslavement ratio back towards teenage girls.

Paba pointed out that often the chidlren of a slave would be also exported as slaves, and so too would their wives. But Thaoa said that Paba wasnt trying hard enough, and promised that if Paba did not provide them a reliable supply of teenage girls that they would start adbucting teens off the streets and not pay fotr them. Paba did not take this threat seriously, as even though the Thaoan slave gatherers were heavily armed, the logistics of abducing a girl and getting all the way to Thaoa without being stopped were out of their reach, with the sole exception of those towns that were already on the border with Thaoa. As a precautionary measure, Paba created a buffer zone of about 15 miles from which no slaves could be deported, but did not publicize this as they didnt want Pabaps crowding into that border strip.

Thaoa suggested Paba fix its slavery problem by making a list of fake crimes that applied only to females, particularly young ones, and punishing people who committed these crimes with slavery. For example, girls caught wearing overly revealing clothing could be enslaved. Paba refused this as well, to Thaoa's dismay.

Paba decided to allow people to sell off their daughters to slave traders voluntarily, though they expected few people would take this opportunity. Sons could not be sold. However, they massively increased the price of a female slave to about 8 times what a male slave cost, figuring that a female slave could produce 8 children, and passed 7/8 of this price on to the family of the slave rather than keeping it for the government. The price needed to be high because Paba knew that few people would willingly sell off their duaghters, knowing they'd nevber be seen again. Paba tried to dress it up, saying that they were creating a "female army" to invade Thaoa and do hard work on the Thaoan farms. Like a traditional army, the life of these soldiers would be painful and dangerous, but they would be doing it for the good of their families anf their nation.

Paba had long been excellent at creating propaganda. A small number of Pabap families agreed with the new propaganda and sold off their daughters, though the Pabap gov't had hurriedly rushed in an amendment to the program stating that the girls had to be at least 13 years old and would be questioned before they left to make sure their parents were not coercing them. Paba also sent some government officials into Thaoa to make sure the slaves were not being abused more severely than Paba was willing to tolerate. Paba also took a census of all of the slaves, making sure it was jsut below the level at which Thaoan farmers would stop needing more slaves. All of this was paid for by Thaoa rather than Paba.

Paba looks south

Nevertheless, Paba realized that Thaoa was only a middle-sized nation, and although it was aggressively expanding to the north and east, most of the territory they were growing over was mountainous and did not seem like an ideal place to put up new plantations. If Paba wanted to continue to sell its bottommost people as slaves, they realized they might have to eventually find new customers.

Paba had long had a difficult relationship with the Star Empire on the western shore of the Gold Bay. For hundreds of years, Star Empire ships had been trading with Paba, generally bringing in tropical fruits that Pabaps loved while the Pabaps traded back wooden furniture and manufactured goods such as combs and silverware. But hidden amongst these friendly trading ships were pirates seeking slaves. They pretended to be normal trading ships, and would try to land near or between actual trading ships, and blend in with the other sailors. The scam would only be noticed when the Pabap merchants buying pineapples looked behind them and noticed their wives were suddenly gone. Sometimes, though, the pirates were even more aggressive, and would raid beachside towns at night stealing all of the people they could find and feeding them the absolute minimum amount of food needed to survive the long journey back to Star territory.

Paba figured that the Stars' repeated kidnappings of Pabaps despite the presence of other nations in between showed that the Stars strongly admired Pabaps and Pabap culture, and wanted to try to turn this into a positive and mutually beneficial relationship. Since the Star ships generally just beached on the coast and then left, this meant that the Stars were only taking slaves from the coast. They offered to open up the entire empire of Paba to Star slave traders if they only would follow the rules that had been put in place for Thaoa, which meant stopping illegal slave raids and paying higher prices for female slaves.

The government of Paba told the Star Empire that they both agreed that slavery was morally acceptable, and Paba would profit from an expanded slavery program because they would only sell out their poorest people, and money would be paid to the family members of the slave in compensation for their loss. Star Empire slave ships tended to land in the northernmost area of the Star Empire, as it was closest, but then take them on a long journey to the far south, to tropical rainforests, partricularly those of Katō.

But the Stars told Paba they were mistaken: the only Star ships taking slaves were illegal ones, and they were going to the equatorial rainforest, where the Star governmen was weak. The Star government itself did not actually need or even want any slaves because they, like Paba itself, had a wage-labor system on their farms and felt that adding slaves would drag down their economy.

Many additional illegal slave raids occurred, and Paba fought several wars against Thaoa to try to rescue these people and their descendants. Note that Thaoan slavemasters were fully entitlted to all of the children of all of their slaves, and did not need to continually pay money to the families in Paba from which they had been bred; thus, Thaoans tried to keep Pabap women pregnant as much as possible, and had an incentive to keep their slaves healthy and at least sometimes happy so that they provided Thaoa with a reliable supply of Pabap children. They figured that sexual intercourse was so enjoyable that even the life of a slave could be made happy by allowing them to procreate as much as they wanted. The Pabaps sent Thaoa a roughly equal balance of men and women so that the population of Paba itself would not be disrupted but yet the Thaoans could easily reproduce more and more Pabaps without having to worry about male slaves dying childless.

A farmer who found himself owning too many Pabap children could sell them to another slavemaster and make a handsome profit. Soon this became a source of money in itself and farmers became the wealthiest class in all of Thaoa. On the other hand, Thaoa realized they were rapidly infesting themslbes with an explosion of Pabap people who could threaten the government of Thaoa itself. They tried to sell the slaves to other nations, but no nations nearby were interested in buying slaves at the moment. The Star Empire was interested in Pabap slaves, but they preferred to simply go to Paba, which was closer. Moreover most Star slave boats were illegal. Thaoa generally did not want to simply let the slaves move back to Paba, as there were seemingly always farmers looking for more slaves even when other farmers had too many. If a slaveowning family died, the slaves were distributed according to the most recently living adult member's wishes.

One political group in Thaoa began to push for a law that would prevent the freeing of Pabap slaves, reenslave the free Pabaps living in THaoa, and allow enslavement of Thaoan criminals. Since this law would even apply to orphaned children, Paba told the THaoans they wanted an amendemnt that allowed Paba to take in orphaned children to prevent them from being enslaved. Thaoa agreed to this, as they knew that Paba was not as weak as they often seemed to be.

Another political group in Thaoa wanted Paba to let Thaoa take over its farm system and enslave even the Pabaps living in Paba. Paba refused, because they knew that Thaoa was only interested in enslaving Pabaps and not any of the other peoples living in Paba, such as the Tarpabaps.

Even though Pabap people were known to be soft and gentle, they were impressive whenever they mobilized for war, and Thaoa did not want to risk entering a war while sitting on a class of people who had every reason to disrupt the war and turn every victory into a defeat. Thus, Thaoa was careful to always stay friendly to Paba during wars, and on those rare occasions when Paba declared war on THaoa itself, Thaoa collapsed early on without mobilizing its whole army.

Exploration of the north

In Paba living standards were actually better in the cold, unsettled north, a land which had come to be called Pupompom. Paba by 1700 AD was already overcrowded, and although its people generally had enough food, they were dependent on networks of trade either from Pupompom or from various nations around them, and if any of these networks broke down, people could starve. They were not the only nation that suffered from overpopulation, but they were among the most aggressive nations at exploring the frigid north, hoping to find a place to live that had a more reliable food supply, even if it meant wearing fur coats all year long.

The Thousand Year Peace

Around the year 1700, Paba ceased fighting wars and entered the Thousand Year Peace (Paubabi Pumau Bapababe). This was a period where Paba was protected by its strong military from needing to depend on foreign powers, thus preventing Paba from being pulled into foreign wars it did not support, and from being invaded by other countries. They did not object when the majority-Pabap states of Punsam and Pombi left to become par of the Subumpamese Union. people in these states said they were not rejecting Pabap culture or religion; they were merely joining the Union because they accepted multiculturalism and wanted to enjoy the economic benefits of being part of a multicultural society led mostly by the Subumpamese.

Thus Paba had a foothold in a foreign nation without compromising its own, and soon came to dominate the coastline of Subumpam even beyond the historical Pabap states' borders. The city of Pipaippis became the wealthiest city in Subumpam and Pabap ships controlled its harbor. On the other hand, many Subumpamese and other peoples moved into the historic Pabap homelands, since the Subumpamese Union allowed free migration from any state to any other state.

The Famine of 1823

In 1823, a cold spell brought famine to the piney habitats of the Pabaps and their neighbors on all sides. Thaoan farmers, finding their plantations suddenly useless, could not produce enough food to feed the Thaoan peasant class. Many sold their Pabap slaves as meat to feed the peasants and then used the money to move to Paba in search of a more reliable food supply. Meanwhile, Nama had also sent people into both Subumpam and Paba to collect food. Paba cooperated with the Thaoans and Namans because they did not want to spoil their long period of peace. Pabaps called the invaders "rabbits" because like rabbits they bothered people only when they needed food, and seemed to be growing rapidly in numbers and molesting the Pabap popuilaton.

Thaoan refugees were generally self-sufficient once Paba gave them money to buy boats, but many Pabap fishermen were afraid when they learned that the Thaoans had financed their journey into Paba by selling Pabaps in meat markets. They did not want to live amongst a people who saw Pabaps as something to have for dinner if a fishing trip turned up empty. Fishing in this age was largely accomplished with boats and spears, so fishermen were essentially as well-weaponed as soldiers, but with no body armor, and a fight amongst fishermen could result in more deaths than a small war. Thus the Thaoans mostly stuck together in rder to avoid conflict with Pabap fishermen (the Pabaps had had to buy rights to the seacost from the gfov't). Meanwhile, Namans were all from mountain tribes unfamiliar with how to fish the ocean.

Paba nonetheless did not try to stop the incoming refugees, and even offered to take in the refugees that were spilling into Subumpam, figuring they couldat least hire them as underclass workers in Paba and thus free up their own underclass to do more profitable work such as piloting ships further out to sea in search of more fish. As it happened, though, Paba's government was unable to coerce the immigrants to work for food, and the Namans often chose to simply move back into Subumpam when they were told the free food was about to stop. Subumpam also required the Namans to work for their food, but the work they did was of very limited quality since they could not speak Subumpamese, and Subumpam considered itself to have been saddled with a problem even worse than Paba's.

Pabap diplomats told Nama that they were terribly sorry they could not feed the Namans for free, as they really did consider Nama a strong ally and did not want to even so much as drift to neutral, but they said Paba was already a famine-prone country and could not even feed itself without relying on buying food from other nations around them. They offered to buy food from the Star Empire and sell it to Nama, even though the price of this food after it had been through three empires would be very expensive. Nama refused the offer, since the journey was so long that they hoped the famine would be over by the time the new imports reached Nama, and Paba had demanded payment up front since it did not want to risk dumping unsaleable goods on itself if Nama backed out of the offer after the cargo ships had arrived.

They also offered to send Namans to the southern reaches of the Star Empire, where many Pabap people were held as slaves by the Star government and would work for them in plantations that were too tropical to be affected by the cold wave. Nama refused this offer as well, as they knew a Pabap ship would likely be refused entry and did not want to run the risk of being sold into slavery along with the Pabaps who had brought them there. the end, Nama held no grudge against Paba, saying it had tried harder than expected to help out and that Nama was the only empire who seemed to be unable to handle the famine on its own, as even Thaoa had regained self-sufficiency within a year.

Meanwhile, Subumpam declared war against Nama and occupied the region of Nama from which the refugees had been coming, which they named Wimpim. They had suffered much more than Paba because Subumpam was smaller than Paba and had had its food production drop much more than Paba but yet had far more Namans move in.

Recovery

Thaoa recovered from the famine quickly. Even though the summer of 1824 was also cold, Thaoa had shifted its attention towards the coast, including the coasts of nations to their east, and now ate a mostly fish-based diet. However, once the weather warmed up again, they were unsure what to do. Thaoans had literally eaten up all of their Pabap slave laborers, and were unwilling to work on farms themselves. They knew that they needed to go to Paba to get more slaves if they expected to remain self-sufficient without becoming dependent on other nations' fish supplies, as they figured that Repilian tribes would eventually take control of their own coastline.

Altogether, about 160,000 Pabaps had been slaughtered and sold in meat markets during the famine to feed desperate peasants in Thaoa. Thaoa thanked the Pabaps for their crucial role in preventing starvation in Thaoa but told them they needed to send Thaoa another 160,000 slaves so that Thaoa could regain self-sufficiency. Paba was surprised at the high demand, as this would be almost 1/4 of Paba's adult population. Even when Thaoa spiced up the deal by offering Paba their cherished recipes for braised human thigh, Paba was unsure they could manage such a huge population transfer. But Thaoa was desperate, and Paba quickly yielded to the temptation of the huge sums that Thaoa was willing to pay Paba's government for their complicity.