Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

..... Pronouns

..

Here, for a transitive clause, "that which initiates the action" is called the A argument, and "that which is affected by the action" the O argument. Also, for an intransitive verb, the noun is called the S argument. It is convenient to make a distinction between all three cases. I follow the linguist RMW Dixon in using this terminology.

In most languages the S argument is marked the same way as the A argument. However in some languages the S argument is marked the same way as the O argument. These are called ergative languages. béu is one of these ergative languages. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative.

Below are the béu pronouns for the S and O arguments. This form can be considered the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

Below are the pronouns for the A arguments ( the ergative arguments ).

Pronouns differ from nouns in that their tones change between the ergative and the non-ergative form. This is in addition to the normal suffixing of -s when a noun becomes marked as ergative.

..

| I | pás | we | yúas |

| we | wías | ||

| you | gís | you | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

jè and jés are the second person plural forms.

yùa and yúas are first person exclusive forms. That is they exclude the person being talked to.

wìa and wías are first person inclusive forms. That is they include the person being talked to.

There is one other pronoun ... the reflexive pronoun tí. This is always an O argument. Notice that it is the only O argument with a high tone.

There is a strong tendency for it to come after the A argument. For example ...

jonos tí timparu = john has not yet hit myself

This particle can be amalgamated to the infinitive to give a reflexive infinitive. For example ...

timpa = to hit ... ti.timpa = "to self-hit"/ "to hit oneself"/"to hit yourself"

[ A dot is used to show that the word comprises two separate elements. I suppose most linguists would use "=" to show cliticisation. The dot makes no difference to the pronunciation ]

..

..... Word order

..

In English it is the order of the verb and the arguments that shows who is the doer and what is the "done to". Namely the A and S argument come before the verb and the O argument after.

[ English is a non-ergative language and hence the A and S argument get treated in the same way. ]

In béu, to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", the suffix -s is appended to the A argument. For example ...

glás bàu timpori = The woman has hit the man

glá bàus timpori = The man has hit the woman

bàu doikora = The man is walking

[ béu is an ergative language and hence the O and S argument have the same form. ]

But even though béu doesn't use word order to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", it does use word order for another purpose. Namely to show if an argument is definite* or not. For example ...

bàu doikora = The man is walking

doikora bàu = A man is walking

So we see ... an argument coming before the verb is definite and one coming after the verb is indefinite.

[ *And when we say definite, we mean that the person being spoken to can identify X as one particular X instead of some X or any X. ]

In English only 2 orders are found. Namely ... SV and AVO ... (V = verb). However in béu you have what is called "free word order". This means that you can come across the following 8 orders ... SV, VS, AVO, AOV, VAO, OVA, OAV and VOA.

But actually in a piece of discourse, it is most likely that the S or A argument are old information and probably the topic (the thing that you have been going on about for some time). In béu an established topic is usually dropped and so the 8 sentence types shown above collapse into 3 sentence types. Namely ... V(s), O V(a) and V(a) O

[ V(s) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the S argument and V(a) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the A argument ]

..

..... The case system

..

We have just mentioned the ergative case. In total there are 17 cases of course (if you were to include the unmarked case as well you have 18 different forms). They are called the pilana.

These are suffixed to a noun and show how that word stands in relation to the rest of the sentence.

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila (v) = to place, to position

pilana (a, n) = positioning, the positioner

Specific Location

The first 8 define location.

1) -pi = in

2) -la = on

3) -mau = above, over, on top of

4) -goi = below, under, underneath, beneath

5) -ce = this side of

6) -dua = beyond, at the far side of

7) -bene = right, at the right hand side of

8) -komo = left, on the left hand side of

These are used to give a location with respect to some object. For example …

nambopi = in the house

nambomau = on the house, over the house

[ Note ... in a lot of situations, where "on" would be used in English, "above" is used in béu. For example ...

"John is on the mountain" = "jono pobomau" not "jono pobola" ]

Roll

The next 4 define the roll that the noun plays in the sentence.

9) -tu = with, using

10) -ji = for, for the benefit of

11) -s = “the ergative case”

12) -wo = about, with respect to

bàus glaji nambo bundori kontotu = the man built the house for the woman with a hammer

gala bauwo catura = the women are talking about the man

[ There are a number of words which end in n. For these words the ergative case is indicated by adding -sə. For example ...

yaivanzə gador wìa = "possessions slow one down" : Note ... this is the only instance of a word final schwa ]

Motion

The next 2 specify motion.

13) --n = to

14) -fi = from

Now these are used to give a motion with respect to some object. For example …

nambon = to the house

nambovi = from the house

[ For words ending in n, the dative suffix is -on. For example ...

nén = what, nenon = to what : mín = who, minon = to who ]

General Location

The next is a “general locative”.

15) -ʔi = at, on, in

glá (yú) pà (sòr) namboʔi = My wife is at home

flovan gì pazbaʔi = Your food is on the table

boloŋgai flovanʔi = the flies are at the food (some buzzing around and some crawling on the surface of the food)

boloŋga flovanʔi = the fly is at the food (sometimes buzzing around and sometimes crawling on the surface)

boloŋga flovanla = the fly is on the food (i.e. its legs are touching the food)

Hybrids of motion & position

The last two define motion AND position. They are sort of hybrids of the second pilana and the pilana of motion.

16) -lna = onto

17) -lfe = off

..

... As parts of speech

..

pilana of location phrases (i.e. nouns with 1 -> 8 or 15) can be considered adjectives if they come after a noun and adverbs if they come after a verb. They must come after a noun or a verb. Sometimes they come after the copula*. In this case they are adjectives. Now often the copula is dropped ... but if this dropping results in any ambiguity it can be readily "undropped".

pilana of motional phrases (i.e. nouns with 13, 14, 16 or 17) can be considered adverbs. They can come in any position because it is understood that they are qualifying the verb.

pilana phrases defining sentence rolls (i.e. nouns with 9, 10, 11 or 12) can come anywhere. They are considered nouns.

* [ Notice that in English, you can either say ... "a bird is in the tree" or "in the tree is a bird"

In béu only jwado (sòr) ʔupaiʔi is valid ... also note that in this case jwado is not definite because it is left of the verb. That rule doesn't work with the copula. ]

..

... Stand alone forms

..

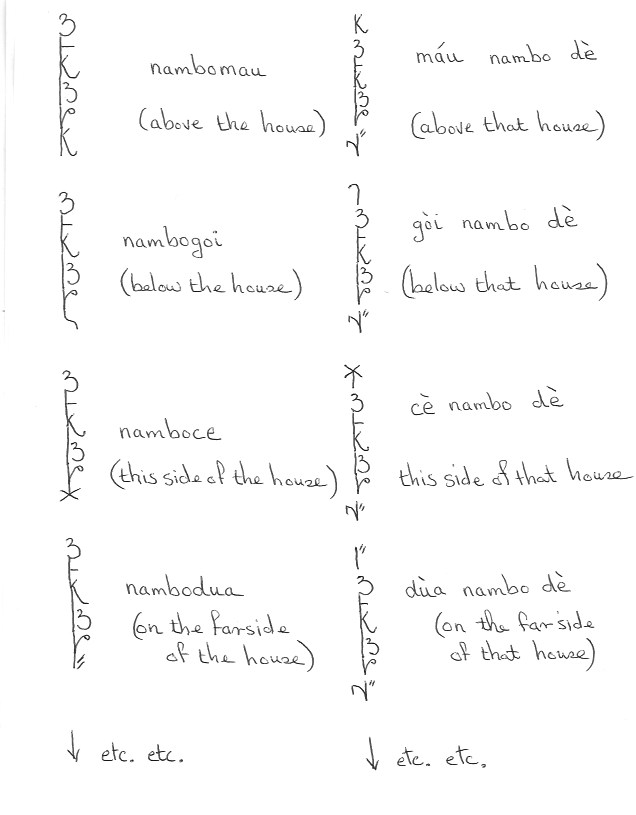

In all the above examples the noun that the pilana qualifies is a single word. However when the pilana qualifies a NP the pilana is not a suffix but appears as an independent word. This particle comes before the NP. For example …

nambodua = beyond the house

dùa nambo yinkai hauʔe = beyond the house of the pretty girl

Below are the forms that the pilana take when appearing as independent words ...

1) pí = in

2) là = on

3) máu = above

4) gòi = below

5) cé = this side of

6) dùa = beyond, at the far side of

7) bene = the right hand side of

8) komo = the left hand side of

9) tú = with, using

10) jì = for

12) só = “the ergative case”

11) wò = about, with respect to

13) ná = to

14) fì = from

15) ʔí = at, in, on

16) alna = onto

17) alfe = off

..

... Script truncations

..

Another thing that sets the pilana apart from other particles, is that they are never written in full. Whether appearing as affixes or independent words, the vowels are always dropped.

The letter "y" represents alfe and the letter "h" represents "alna".

..

..... The fandaunyo

..

fandau = noun*

fandauza** = "a noun phrase"

fandaunyo*** = "a noun or a noun phrase"

*The usual word building process would give fanyədau (from nandau "word" and fanyo "thing/object"). However in this particular word, there has been a further contraction to fandau.

** the suffix -za, is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word".

*** the suffix -nyo, is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word OR the basic word.

..

The countable nouns fandauza

..

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| ------------------- | ----------------- | --------------- | ------------- | ---------------- | ----------------- | ------------------- | ------------------- |

| emphatic particle | specifier | number | head | adjective | determiner | question word | relative clause |

| koiʒi | hua | saidau |

Only the head is mandatory.

Actually there are quite a few restrictions. For example (7) would never occurs with (8) .... mmmh why did I insert "would" here ??

Many restrictions between (2) and (3)

..

The question words

..

The set of possible question word (within a NP) is very small. Only three ... nái "which", láu "how much" or "how many", kái "what kind of".

..

The determiners

..

The set of possible determiners is very small. Only two ... dí "this", or dè "that".

..

The adjectives

..

Not much to say about this one, you can string together as many as you like ... the same as in English. Also genitives are put in this slot. A genitive is a word derived from a noun by the suffixing of -n (or -on) which indicates possession*. Genitives always come after the regular adjective.

*Actually it can also stand for a location ... where the NP is at.

..

The head

..

This is usually a noun. However it can also be an adjective. When it is an adjective it has concrete reference instead of representing a quality (as happens often in English). For instance, when talking about ... say ... a photograph, you could say "the green is too dark". In this sentence "the green" is a NP meaning the quality of being green. In béu if green is used as the head of a NP it always means "the green one" : "the person/thing that is green".

In béu, geunai would be used in a sentence such as "the green is too dark".

gèu = "green" or "the green one"

geumai = "greenness"

saco = "slow" or "the slow one"

saconi = "slowness"

Notice that the suffix has two forms ... depending upon whether the base adjective has one syllable or more than one syllable.

Sometimes the head is a determiner. In these cases the NP is understood to refer to some noun ... but it is not spoken ... it is just understood by all parties. In these cases the determiners undergo a change of form ...

dí => adi = "this one"

dè => ade = "that one"

nái => anai = "which one"

Related to dí and dè are the two nouns dían (here) and dèn (there). Although nouns, they never occur with the locative case or the ergative case.

..

The specifiers

..

The specifiers = nandau.a koiʒi or just koiʒia

koiʒi actually means "preface" as in "the preface to the book" ... ??? or may be I could call it :head" ???

It also means forewarning or harbinger ... as in "that slight tremor on Tuesday night, was koizi of the quake on Friday"

Immediately before the core you can have a specifier.

The specifiers are ...

| jù | no | ù | all | ||

| í | any | é | some | è | ....... some (plural) |

| nò | plural | ||||

| auva => | ataitauta | numbers | (2 => 1727) | ||

| uwe | many | iyo | few | ||

| ege | more | ozo | less |

..

Notice that the specifier that implies zero number has low tone, the 3 specifiers that imply singular* number have high tone and the 3 specifiers that imply plural* number have low tone.

.* Well this is true for the English translations anyway. (Side Note ... Actually I am not so sure about the "logic" of my little scheme. Also I would like to look into how a spectrum of other languages use specifiers)

Also note that nò is a noun (meaning "number") as well as a particle that denotes plurality. In the béu mathematical tradition, nò means a number from 2 -> 1727 only (of course there are expressions for expanding the concept to integers, rational numbers etc. etc.)

After a koiʒi the head is always in its base form with regard to number. For example ...

..

é glà = some woman

è glà = some women ... not *è gala

í toti = any child .......... not *í totai

..

The are 4 cases where you can have two koiʒi together ... é nò or when you have í followed by a number greater than one. For example ...

..

é nò toti = some child or children ... this is a contraction of "é toto OR nò toti"

í auva toti = any two children

ege auva toti = two more children

ozo auva toti = two less children

..

The emphatic particle

..

Now even before the specifiers it is possible to have an element. This is the emphatic particle á.

This is also used as a sort of vocative case. Not really obligatory but used before a persons name when you are trying o get their attention.

When this particle comes directly in front of adi, ade and anai an amalgamation takes place ( á adi etc etc are in fact illegal)

á adi => ádí = "this one!"

á ade => ádé = "that one!"

á anai => ánái = "which one!"

These three words break the rule that only monosyllabic words can have tone. These 3 words are the only exception to that rule.

By the way, emphasis is always used when contrasting two things. as in "this is wet, but that is dry" = ádí nucoi, ádé mideu

When written using the béu writing system, only the initial a is given the dot on the RHS which indicates high tone. The second syllable is unmarked.

..

The relative clause

..

béu relative clauses work pretty much the same as English relative clauses.

bàu à glás timpori = the man whom the woman hit

bàu às glá timpori = the man who hit the woman

The relativizer is à or às. à if the NP has an S or O role within the relative clause ... às if the NP has an A role within the relative clause ... béu being an ergative language.

..

The uncountable noun fandauza

..

It can consist of ... (1) "the holder" ... (2) the head hua ... (3) adjectives saidau ... (4) a determiner didedau. Only the head is mandatory.

auva hoŋko ʔazwo pona dí = two cups of this hot milk

Note ... even though we have no word "of" ... there is no ambiguity. If the above was two fandaunyo, there would either be a pause between hoŋko and ʔazwo (for example if one was A and one was the O argument), or they would be separated by "and" wí if they were separate fandaunyo but comprised only one argument.

In this respect béu takes after Indonesian. For example ... five big bags of this black rice = lima tas besar beras hitam ini (literally ... five bag big rice black this)

Note that the "holder ???" can be a complete countable noun fandaunyo in itself.

lima tas besar beras hitam ini

(5 bag big) (rice black this) .... Usually languages have a linker, particular when the phrases are long. For example Chinese "de", English "of", Japanese "no". béu has no linker (similar to Indonesian) ... (however à or fí could be pressed into service if needed ??? )

(SideNote) ... ʔazwe = to suck ... ʔazweye = to suckle, to offer the breast

..

The pronoun phrase

Below is a table with nù "they" occurring with the allowed specifiers. yùa, wìa, jè and ʃì pattern in a similar way.

| 1 | í nù | any of them |

| 2 | é nù | one of them |

| 3 | yú nù | every one of them |

| 4 | è nù | some of them |

| 5 | kyà nù | none of them |

| 6 | ù nù | all of them |

| 7 | kyà nù | none of them |

| 8 | í auva nù | any two of them |

| 9 | ege nù | more of them |

| 10 | ozo nù | less of them |

Nothing really surprising in the above. However I thought that I should lay it out in black and white. (what about emo "the most" and omo "the least" ??)

..

Because the person and number of the A or S argument is expressed in the actual verb. The above are usually dropped (however the third person pronoun is occasionally retained to give the distinction between human and non-human subject) so when the pronouns above are come across, it might be better to translate them as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

It is a rule that tí must follow the A argument (if it is overtly expressed ... i.e. by a free-standing pronoun and not just in the verb)

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

..

There are 4 types of noun phrase in béu ...

..

1) The noun phrase for countable nouns

2) The noun phrase for uncountable nouns

3) The noun phrase for pronouns

4) The noun phrase for verbs

5) The noun phrase for places

..

..... hipe & hipeza

..

Now a hipe or "infinitive" is a type of noun. So it can be the head of a NP ( fandaunyo ) using the rules as given previously.

However there are additional restrictions compared to a normal fandaunyo ... namely they never take plurals and are never possessed (that is followed by yú ).

However there is a second type of NP allowed. This also has a hipe core. However the A O, O, A or S arguments are directly incorporated into this second type of NP. It is called a hipeza.

These two types are distinct ... apart from the case where you have a hipe standing alone.

So there is no direct translation of the term NP. Instead NP must be translated as either fandaunyo, hipeza or hipe.

[ and pronouns as well I suppose, if you consider "pronoun" to be a subset of NP in English ]

Below are the five forms that the hipeza can take.

timpa . báu . glà = the man's hitting of the woman

timpa glà hí báu = the man's hitting of the woman

timpa glà = the hitting of the woman ... (note that this can be ambiguous in English)

timpa hí báu = the man's hitting ... (actually you wouldn't say this in English. I don't know why)

doika jono = john's walking

The first and second mean the exact same thing ... nothing at all wrong with a bit of redundancy.

Other elements relating to time, place and manner can come after the S, O and A arguments. However they are not considered part of the hipeza core.

In the first form ,,, the inter word dots represent a pause that is required by the grammar. Maybe you could have pauses elsewhere ( for example if the speaker was panting ) ... but these pauses wouldn't change the meaning of the phrase : the two pauses in the first example are mandatory.

In a hipeza béu is quite strict on how arguments can be added. English is a bit chaotic when it comes to this. For example ...

Attila's destruction of Rome

Attila's destroying of Rome

Rome's destruction (by Attila)

The destruction of Rome (by Attila)

The destroying of Rome (by Attila)

---two old ideas------------

The S or A argument (if it exists or is mentioned) must come before the hipe. It is preceded by hí (the same particle that indicates the agent in the passive construction)

The O argument (if it exists or is mentioned) must come after the hipe. It is followed by jwìa (possibly related to jwèu ... "to endure" ( but if it was this would mean this construction takes two subjects ??)

Often in fast speech, hí and jwìa are dropped, but they are always available to make things clear.

The sandaunyo is similar to the fandaunyo but built around a sandau as opposed to a fandau.

sandau = a verbal noun, an infinitive, a maSdar .... whatever you want to call it. Ultimately derived from the word sanyo which means "an event". (fanyo and sanyo are equivalent to the Japanese "mono" and "koto"). The word for "verb" is jaudau. Of course there is a one to one relationship between the jaudau and the sandau (as in English if you have an infinitive verb form, you are of course going to have a corresponding finite verb form).

Tie in the participle phrase ... wanting to get a ride, John went down to walking street.

..

..... Possession & Existence

..

The verb yái means "to have on your person" or perhaps "to have easy access to" if we are talking about a larger object. For example ...

jonos yór ama = John has an apple

As with all transitive verbs it has a passive form.

jono yawor = John is present .... short for jono yawor hí día

ama yawor hí jono = The apple is on John's person

....

The verb wàu means "to possess legally" to "own"

jenes wàr wèu = Jane owns a car

And the passive form ...

wéu wawor hí jene = The car is owned by Jane

....

yái is also used to show location.

ʔupais yór bode = "there are small birds in the tree"

Note ... a copular expression can also be used to express the above ...

....

"There is a God" => God is real

"There is no God" => God is imaginary

....

’’’yái’’’ = to be in possession of (on you) …….……. ability => sometimes

‘’’wàu’’’ = to possess (legally) ………………………. obligation/duty => inevitability

..

..... Punctuation and page layout

..

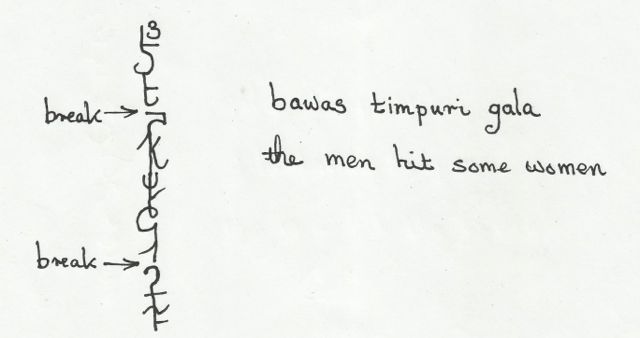

The letters in a word are always contiguous, that is there is always a line running right through the word. Writing is firstly from top to bottom and secondly from left to right.

Between words there is a small break in the line. See the figure below ...

..

..

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, this small break would be indicated by dù

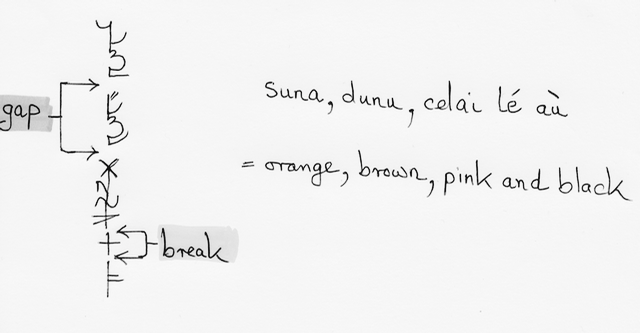

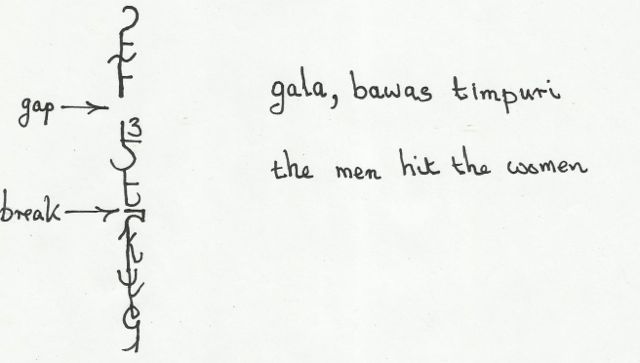

Between some words there is a gap. This represents a pause. A pauses in English is represented by a comma, a colon or a semicolon. Whenever an orator draws breath, this will be reflected in the writing by a gap. Also there are occasions where the grammar of béu demands a gap. When such a gap is required I will represent in in my transcription as an inter word dot. For example ... ‘’’suna . dunu . celai lé àu’’’ = orange, brown, pink and black

Presumable in English, commas originally were always used for pauses in speech. However nowadays in English many pauses are not represented in any way (presumably in these cases when it is not necessary for reading comprehension). Also in English, in a surprising amount of text commas are found where they shouldn't be. In béu gaps in a textblock have a one-to-one correspondence to a pause in speech.

*When listing items, béu is similar to English ... there is pause between every item except the last two items. Between these items, béu has lé, English has "and".

..

..

..

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, the gap is indicated by saying ???

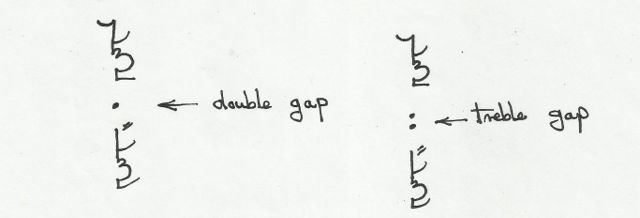

Single gaps are very common. Occasionally you can have "double gaps" and even "treble gaps". These rare creatures represent "pregnant pauses" which are sometimes used for comic effect.

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, a "double gap" is rendered by bauva ??? , a treble gap by baiba ???.

Note the single point used in the "double gap" and the pair of points used in the "treble gap".

..

..

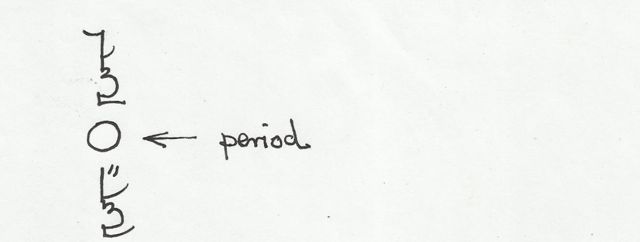

There is also a punctuation mark called the "sunmark" ( kòi = sun ). This is basically a full-stop. The "sunmark" has double the diameter of omba (omba means "circle" and is used as a decimal point).

..

..

There are also punctuation marks called "moonmark" ( dèu = moon ). These are basically brackets. The opening one is called "moonmark" damau and the closing one is called "moonmark" dagoi. Direct speech is enclosed in "moonmarks". These bits of direct speech are also highlighted. Usually the first speaker's words are highlighted in blue and the second speaker's words are highlighted in yellow. The highlighted area is lozenge shape. Every "textblock" the protagonists are reset ??. In a story, after the scene is set ... that is the time of speaking and the identity of the speakers have been established, then their names are dropped from the text and the kloi "speak" is also dropped. However somebody reading the text out loud would give this information from their understanding of the situation.

..

..

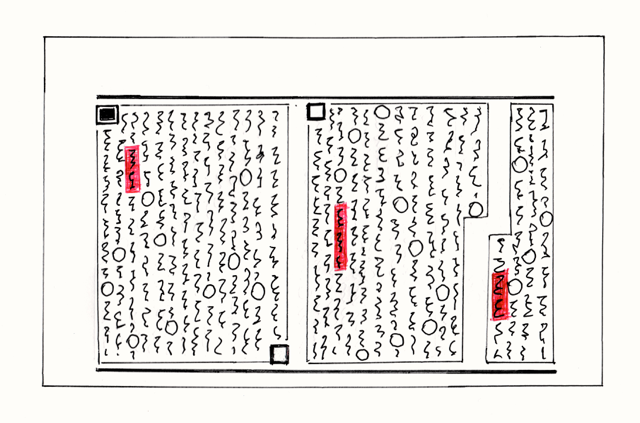

In a normal narrative, everything is written in "textblocks".

(Please note ... the light lines surrounding the "textblocks" are not real. They are just there to assist me drawing)

..

This is the first page in a "chapter". Notice the symbol at the top left hand side of the first "textblock". This is called a "heavy tile".

Textblocks fit in between "rails" about 4 inches apart. The width of a block should be between 60% and 90% * of the block height. Of course it is best to start a new block when the scene of the narrative changes or there is some discontinuity of the action, but this is not always possible. Then you just must arbitrarily split the text into two blocks. The standard practice is to stretch the text a bit so that the tops and bottoms of every column line up with their neighbours. XXXXXX

There is no way to split a word between two lines (as we can do in the West by using two hyphens). A "sunmark" must be next to the last word in a sentence (it can not go to the start of a new column by itself) However if a "sunmark" fall next to the bottom rail, then the next column will begin with a "sunmark". This is purely due to a love of symmetry.

The first text block starts at the top left (as you would expect). The second textblock starts below where the first text block stops. In fact the vertical space between the stop and the start of the two textblocks is equal to the horizontal "interblockspace" (see the figure above).

If the last "sunmark" of a "textblock" falls next to the bottom rail (as indeed happens with the very first "textblock" of the "chapter", then this "sunmark" is changed into a symbol called a "bottom tile". If a "textblock" ends in a "bottom tile", then what is called a "top tile" will appear before the first word of the next "textblock". This is purely due to a love of symmetry. Note that the "top tile" is exactly the same as the "bottom tile". (Actually in modern printing techniques, the text in complete "textblocks" can be stretched to prevent the final "sunmark" falling on the bottom rail)

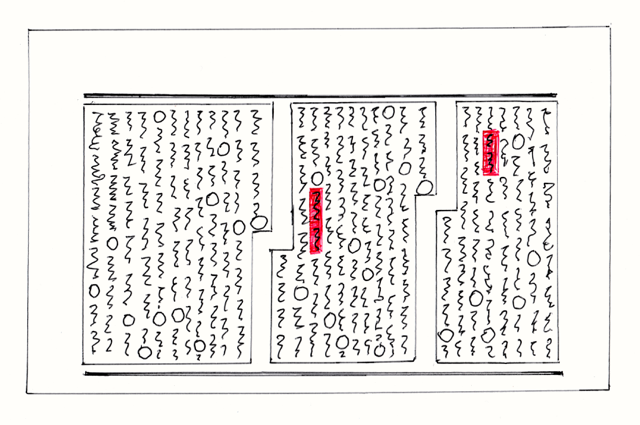

When you come to the end of the page (you will have some sort of margin of course and not go all the way to the edge), you simply continue the block on the LHS of the next rail (or page). Below is the second page of the chapter. This page continues on from the page above.

..

..

In every textblock, one word or short noun phrase is highlighted in red. The shape of the highlighted area is rectangular with rounded edges. Usually a noun is chosen and the more iconic the better. Statistically these highlighted words tend to come towards the beginning of the "textblock".

..

There are two sizes for books. For all hardback books the size is about 8 inches by about 11 inches. For all paperback books the size is about 5 inches by about 8 inches. They are stored as shown in the figure below.

..

..

Unlike books produced in the West, these books are held with the spine horizontal when being read. The hardback page has two "rails" per page (i.e. three dark lines).

On the paperback book, the title is written on the spine and on the front of the book. On the hardback book the title is written on the front, also there is a flap that slides into the spine. However when the book is stored on a shelf, it is pulled out and hangs down. Hence the hardback books can be easily located, even when they are in the bookshelf.

A book will be divided into chapters. A chapter will have a number and usually a title as well. Either at the end of the book or just after the chapter, there will be a page, in which all the highlighted words for a chapter are listed in order. Instead of referencing things by page number, things are reference by chapter and textblock (indictated by the highlighted word(s) ).

Any particular word in a book can be reference by 5 parameters ...

1) "title of book"

2) number of the chapter

3) the highlighted word(s)

4) the number of the sunmarks counted. Actually they are counted backwards ... from the final "sunmark" of the "textblock". Note ... all "sunmarks" are counted, even the ones next to the top rail.

5) the number of the word. This is also counted backwards (i.e. the final word of the sentence is word "1" ... and so on)

* Occasionally very narrow blocks can not be avoided. And of course in mathematical/scientific tracts the tracts are all over the place ... interspersed with diagrams and what have you.

..

..... More on definiteness

..

In the section on word order we said that when the person being spoken to can identify X as one particular X ... then X will come before the verb, where X is any of the A O or S arguments.

However ... the above leaves undefined, whether the person speaking can identify X. This can be made explicit in béu by adding either the particle é or the participle fawai. For example ...

doikora bàu = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known-ness to the person speaking is not defined.

doikora é bàu = Some man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : unknown to the person speaking.

doikora bàu fawai = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known to the person speaking.

This distinction is also made in certain natural languages. For example with nouns in Samoan ...

o sa fafine = a woman

o le fafine = a woman ……. unknown to you but known to me

Or between these two indefinite pronouns in Latin ...

aliquis = somebody

quidam = somebody ……. unknown to you but known to me

[ Note ... the argument qualified by é or fawai invariably come after the verb. Also, while it is possible to imagine some scenario where an argument is known to the person being spoken to but unknown to the person speaking, in reality this very very rarely happens and I know of no natural language that makes this distinction. ]

..

One interesting point .....

Take the sentence ... "She wants to marry a Norwegian"

How do we show the definiteness of the Norwegian in relation to the subject. That is ... does she have a certain Norwegian in mind or does she want to marry any Norwegian.

In English ... when you hear this sentence ... you will nearly always know from the context, which of the two meanings is meant.

"any" or "that she knows" could be added to make the distinction explicit within the sentence itself.

..

..... Correlatives

..

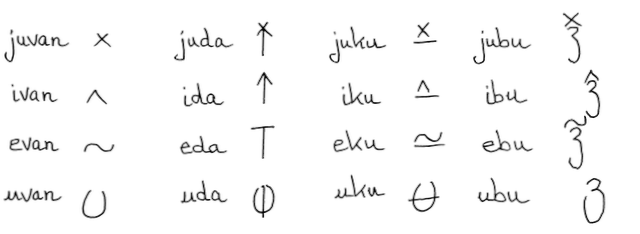

| juvan | nothing | juda | nowhere | juku | never | jubu | nobody |

| ivan | anything | ida | anywhere | iku | anytime | ibu | anybody |

| evan | something | eda | somewhere | eku | sometime | ebu | somebody |

| uvan | everything | uda | everywhere | uku | always | ubu | everybody |

These correlatives are always written in their shorthand form. See the chart above.

The first column is a contraction of jù fanyo, í fanyo, é fanyo and ù fanyo (fanyo = thing)

The second column is a contraction of jù dá, í dá, é dá and ù dá (dá = place)

The third column is a contraction of jù kyù, í kyù, é kyù and ù kyù (kyù = time/occasion)

The last column is a contraction of jù glabu, í glabu, é glabu and ù glabu (glabu = person)

The non-contracted forms are still used, usually when emphasis is wanted.

There is another row in the above table.

This is the plural equivalent of the third row of the table above. The emphatic form of the above series would be ...

è fanyo, è dá, è kyù and è glabu .... if these elements were under* the main verb, it would be more normal to use ...

fanyoi, nò dá, nò kyù and glabua .... and actually, if any word from the third row of the main table came under the main verb, you could just use ...

fanyo, dá, kyù and glabu ... in this position you have probably a 50% chance of coming across evan and a similar chance to come across fanyo ... the same with eda, eku and ebu.

One interesting point is ... well for example ubu can mean "each person" and "all the people". If ubu was the S or A argument there could be one of two verbs in a SVC. One would have the meaning "to do together"/"to cooperate" and the other would have the meaning "to work alone". If ubu was the O argument or has some other roll in the sentence there is a partical that can be put in above* ubu. This particle means something like "individual" or "independent" and would disambiguate the meaning of the béu sentence.

*I was going to say 'after" and "before", however as the béu writing system is vertical I thought I should get in the spirit of things and use "under" and "above".

..

..... Ambitransitive verbs

..

In English there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes involve two participants. For example "knit" or "turn". In English you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up after the verb (that is ... an O argument has turned up) ... S and A appear the same in English.

Similarly in béu there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes take two participants. For example mekeu "knit" or kwèu "turn". In béu you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up with the ergative marker -s attached (that is ... an A argument has turned up) ... S and O appear the same in béu.

Note on nomenclature

Dixon calls "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitive verb of type S=A or an [S=A ambitransitive verb].

I call "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one unaffected argument" or an [unaffected ambitransitive verb].

For "knit" the preverb argument* is either S or A .... For mekeu the unaffected argument is either S or A.

Dixon calls "turn"/kwèu is an ambitransitive verb of the type S=O or an [S=O ambitransitive verb].

I call "turn"/kwèu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one affected argument" or an [affected ambitransitive verb].

For "turn" the affected argument is either S or O .... For kwèu the naked argument** (i.e. no -s) is either S or O.

*It is also the unaffected argument.

**It is also the affected argument.

..

..... Number symbols

..

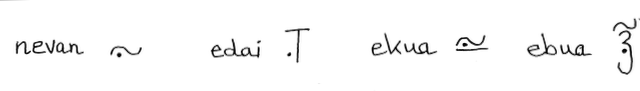

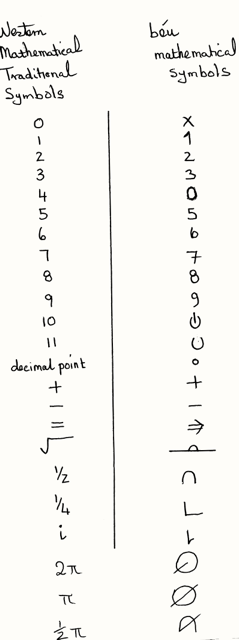

Numbers are never written out in full. As if in English you never came across the word "seven" but also came across "7". Actually in béu there are two ways to write "7" depending on what environment you find yourself..

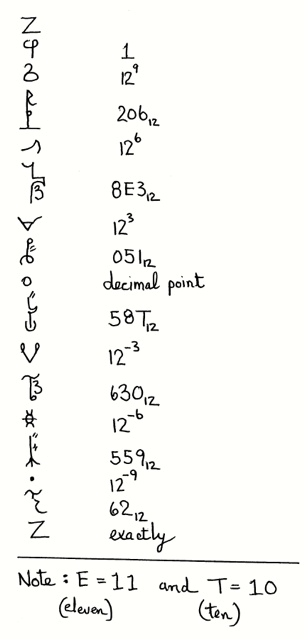

Within a textblock they are written vertically (to fit in with everything else) and are headed up by a symbol that looks like "Z". After that the number is written using the symbol for the consonant part of the basic numbers (i.e. 1 -> 11). The symbol for h is used for inserting zeroes in the textblock form (this h symbol would never be pronounced).*. Magnitude is dependent on position.

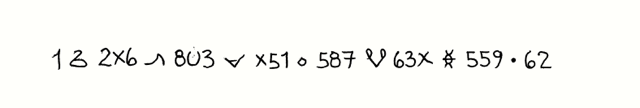

When not in textblocks ( i.e. when on part of a page or a blackboard given over to manipulating mathematic expressions) numbers are expressed by symbols that are based on the Western Mathematical Tradition. This is called the "free form" of the number.

Below is how five numbers (given previously in NUMBERS) would appear in both forms.

..

..

It can be seen that the free form is written horizontally while the textblock form is written vertically.

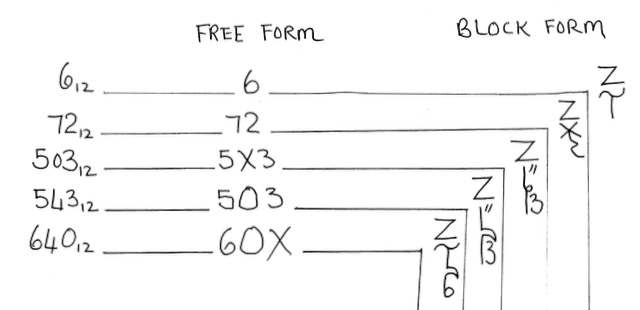

If you have a number string more than three digits long you must have at least one "magnitude" word. The magnitude words and symbols are given below.

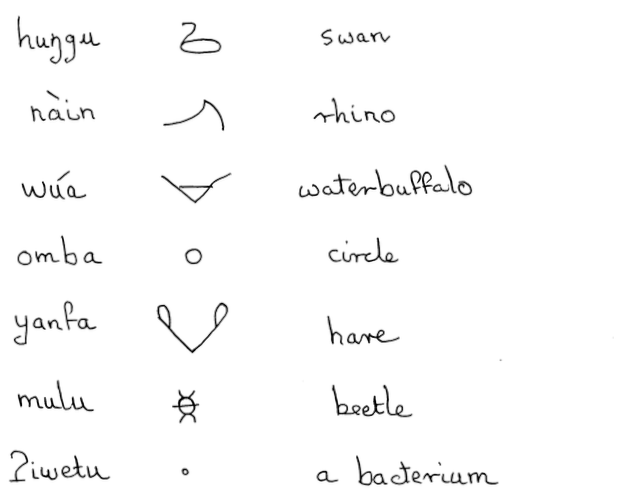

The circle is the béu decimal point. The other marks are equivalent to the comma's that we use to divide up large numbers into blocks of three digits. However instead of only having comma's and decimal points to divide up the number, we have 7 symbols.

Actually all the magnitude numbers are also common nouns as well. These are given on the right-hand-side.

To demonstrate the use of the magnitude words I will introduce a long number. I haven't worked out how to express it in base ten, but in base twelve it is ...

1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... where T represents ten and E represents eleven

In béu it would be pronounced ... aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dù ... notice that all the magnitude words are spoken out.

Below is how this number is written in textblock form.

Amd below is how this number is written in free form.

The 7 magnitude words extend the range of numbers expressible. Remember that béu only actually has words for 1-> 1727. But even with the help of magnitude words, the number range expressible in béu restricted.

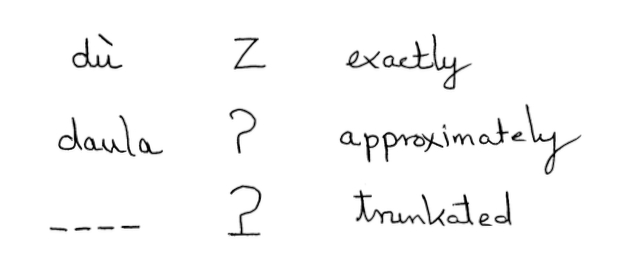

In textblock form a number is aways finished of with one of the three symbols given below ...

These are called exactness words. They are also spoken out when reciting a number.

The "trunkated" symbol means that some digits have been lopped off, rather being rounded up or down. For example, if you expressed "pie" as 3.1415 you would use the trunkated symbol (actually 3.1416 is closer to the actual number than 3.1415).

It should be quite obvious what "exact" means. "approximate" has a rather loose meaning ... basically anything not "exact". The "trunkated" and "approximate" symbols are both usually spoken as daula, There is a more exact technical expression for trunkated (???) but you hardly ever come across it.

Below are some more symbols used in mathematics. Obviously these symbols would be used in a free form area (i.e. the free form part of a page)

..

..

Note ... The symbol for four is not circular. It seems to "sag" ... it is bigger at the bottom than at the top ... not exactly egg-shaped either but ...

*If you had a leading zero you would use the word jù. 007 would be jù jù oica (three words). To deal with a telephone number, you would lump the numbers in threes (any leading zero or zeroes by themselves though) and outspeak the numbers. If you were left with a single digit (say 4) it would be pronounced agai. If you were to pronounce it uga, it would of course mean 004. Also you would probably add the particle dù at the end. This means "exactly" (or it can mean the speaker has finished outspeaking the number).

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences