Béu : Chapter 4 : The Adjective

..... Noun phrases

..

There are 4 types of noun phrase in béu ...

..

1) The noun phrase for countable nouns

2) The noun phrase for uncountable nouns

3) The noun phrase for pronouns

4) The noun phrase for verbs

5) The noun phrase for places

..

From now on I will not be talking about "noun phrase", but will be using the béu term fandaunyo.

fandau = noun*

fandauza** = "a noun phrase"

fandaunyo*** = "a noun or a noun phrase"

*The usual word building process would give fanyədau (from nandau "word" and fanyo "thing/object"). However in this particular word, there has been a further contraction to fandau.

** the suffix -za, is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word".

*** the suffix -nyo, is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word OR the basic word.

..

... The countable nouns fandauza

..

It can consist of ... (1) the emphatic particle ... (2) a specifier koiʒi ... (3) a number ... (4) the head hua ... (5) adjectives saidau ... (6) a determiner ... (7) a question word ... (8) a relative clause. Only the head is mandatory.

Actually there are quite a few restrictions. For example (7) would never occurs with (8) .... mmmh why did I insert "would" here ??

Many restrictions between (2) and (3)

..

.. The question words

..

The set of possible question word (within a NP) is very small. Only three ... nái "which", láu "how much" or "how many", kái "what kind of".

..

.. The determiners

..

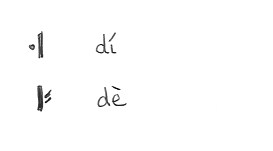

The set of possible determiners is very small. Only two ... dí "this", or dè "that".

..

.. The adjectives

..

Not much to say about this one, you can string together as many as you like ... the same as in English. Also genitives are put in this slot. A genitive is a word derived from a noun by the suffixing of -n (or -on) which indicates possession*. Genitives always come after the regular adjective.

*Actually it can also stand for a location ... where the NP is at.

..

.. The head

..

This is usually a noun. However it can also be an adjective. When it is an adjective it has concrete reference instead of representing a quality (as happens often in English). For instance, when talking about ... say ... a photograph, you could say "the green is too dark". In this sentence "the green" is a NP meaning the quality of being green. In béu if green is used as the head of a NP it always means "the green one" : "the person/thing that is green".

In béu, geunai would be used in a sentence such as "the green is too dark".

gèu = "green" or "the green one"

geumai = "greenness"

saco = "slow" or "the slow one"

saconi = "slowness"

Notice that the suffix has two forms ... depending upon whether the base adjective has one syllable or more than one syllable.

Sometimes the head is a determiner. In these cases the NP is understood to refer to some noun ... but it is not spoken ... it is just understood by all parties. In these cases the determiners undergo a change of form ...

dí => adi = "this one"

dè => ade = "that one"

nái => anai = "which one"

Related to dí and dè are the two nouns dían (here) and dèn (there). Although nouns, they never occur with the locative case or the ergative case.

..

.. The specifiers

..

The specifiers = nandau.a koiʒi or just koiʒia

koiʒi actually means "preface" as in "the preface to the book" ... ??? or may be I could call it :head" ???

It also means forewarning or harbinger ... as in "that slight tremor on Tuesday night, was koizi of the quake on Friday"

Immediately before the core you can have a specifier.

The specifiers are ...

| jù | no | ù | all | ||

| í | any | é | some | è | ....... some (plural) |

| nò | plural | ||||

| auva => | ataitauta | numbers | (2 => 1727) | ||

| uwe | many | iyo | few | ||

| ege | more | ozo | less |

..

Notice that the specifier that implies zero number has low tone, the 3 specifiers that imply singular* number have high tone and the 3 specifiers that imply plural* number have low tone.

.* Well this is true for the English translations anyway. (Side Note ... Actually I am not so sure about the "logic" of my little scheme. Also I would like to look into how a spectrum of other languages use specifiers)

Also note that nò is a noun (meaning "number") as well as a particle that denotes plurality. In the béu mathematical tradition, nò means a number from 2 -> 1727 only (of course there are expressions for expanding the concept to integers, rational numbers etc. etc.)

After a koiʒi the head is always in its base form with regard to number. For example ...

..

é glà = some woman

è glà = some women ... not *è gala

í toti = any child .......... not *í totai

..

The are 4 cases where you can have two koiʒi together ... é nò or when you have í followed by a number greater than one. For example ...

..

é nò toti = some child or children ... this is a contraction of "é toto OR nò toti"

í auva toti = any two children

ege auva toti = two more children

ozo auva toti = two less children

..

.. The emphatic particle

..

Now even before the specifiers it is possible to have an element. This is the emphatic particle á.

This is also used as a sort of vocative case. Not really obligatory but used before a persons name when you are trying o get their attention.

When this particle comes directly in front of adi, ade and anai an amalgamation takes place ( á adi etc etc are in fact illegal)

á adi => ádí = "this one!"

á ade => ádé = "that one!"

á anai => ánái = "which one!"

These three words break the rule that only monosyllabic words can have tone. These 3 words are the only exception to that rule.

By the way, emphasis is always used when contrasting two things. as in "this is wet, but that is dry" = ádí nucoi, ádé mideu

When written using the béu writing system, only the initial a is given the dot on the RHS which indicates high tone. The second syllable is unmarked.

..

.. The relative clause

..

béu relative clauses work pretty much the same as English relative clauses.

bàu à glás timpori = the man whom the woman hit

bàu às glá timpori = the man who hit the woman

The relativizer is à or às. à if the NP has an S or O role within the relative clause ... às if the NP has an A role within the relative clause ... béu being an ergative language.

..

... The uncountable noun fandauza

..

It can consist of ... (1) "the holder" ... (2) the head hua ... (3) adjectives saidau ... (4) a determiner didedau. Only the head is mandatory.

auva hoŋko ʔazwo pona dí = two cups of this hot milk

Note ... even though we have no word "of" ... there is no ambiguity. If the above was two fandaunyo, there would either be a pause between hoŋko and ʔazwo (for example if one was A and one was the O argument), or they would be separated by "and" wí if they were separate fandaunyo but comprised only one argument.

In this respect béu takes after Indonesian. For example ... five big bags of this black rice = lima tas besar beras hitam ini (literally ... five bag big rice black this)

Note that the "holder ???" can be a complete countable noun fandaunyo in itself.

lima tas besar beras hitam ini

(5 bag big) (rice black this) .... Usually languages have a linker, particular when the phrases are long. For example Chinese "de", English "of", Japanese "no". béu has no linker (similar to Indonesian) ... (however à or fí could be pressed into service if needed ??? )

(SideNote) ... ʔazwe = to suck ... ʔazweye = to suckle, to offer the breast

..

... The pronoun fandauza

..

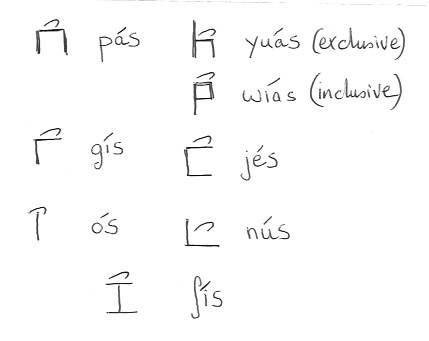

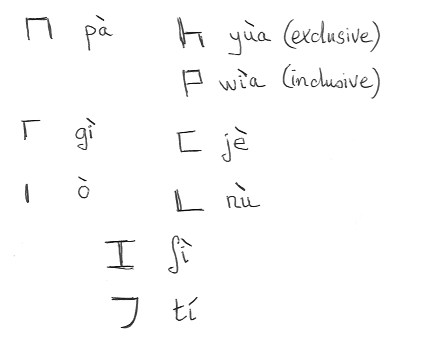

Below the forms of the béu pronouns are the given for when the pronoun represent the S or O argument. This form can be considered the "base form" or the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

When they are used as an S arguments (i.e. with an intransitive verb), it might be better to translate these pronouns as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

..

There is another pronoun but this one only occurs as an O argument. When a action is performed by somebody or something on themselves we use tí to represent the O argument.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in béu we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari. ..

Below is a table with nù "they" occurring with the allowed specifiers. yùa, wìa, jè and ʃì pattern in a similar way.

| 1 | í nù | any of them |

| 2 | é nù | one of them |

| 3 | yú nù | every one of them |

| 4 | è nù | some of them |

| 5 | kyà nù | none of them |

| 6 | ù nù | all of them |

| 7 | kyà nù | none of them |

| 8 | í auva nù | any two of them |

| 9 | ege nù | more of them |

| 10 | ozo nù | less of them |

Nothing really surprising in the above. However I thought that I should lay it out in black and white. (what about emo "the most" and omo "the least" ??)

..

Because the person and number of the A or S argument is expressed in the actual verb. The above are usually dropped (however the third person pronoun is occasionally retained to give the distinction between human and non-human subject) so when the pronouns above are come across, it might be better to translate them as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

It is a rule that tí must follow the A argument (if it is overtly expressed ... i.e. by a free-standing pronoun and not just in the verb)

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

..

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the A argument.

..

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

..... 72 Adjectives

..... 4 of which serve as intransitive verbs

..

| bòi * | good | boizora | she is healthy | bòis** | to be healthy/health |

| kéu | bad | keuzora | he is ill | kéus | to be sick/illness |

| fái | rich ** | faizora | she is interested | fáis | to be attentive/attention |

| pàu | bland | pauzora | he is bored | pàus | to be bored/boredom |

* Note that the adverb version of this word is slightly irregular. Instead of boiwe it is bowe. People often shout this when impressed with some athletic feat or sentiment voiced ... bowe bowe => well done => bravo bravo

**boisis is commonly said upon parting for what is expected to be some time. It means "may you be well".

Also instead of keuwe we have kewe. People often shout kewe kewe kewe if they are unimpressed with some athletic feat or disagree with a sentiment expressed. Equivalent to "Booo boo".

**In a non-monetary sense. If applied to food it means many flavours and/or textures. If applied to music it means there is polyphony. If applied to physical design it means baroque.

..

... 12 of which don't serve as any type of verbs

..

| igwa | equal, the same |

| uʒya | different, not the same |

| sài | young |

| gáu | old (of a living thing) |

| jini | clever, smart |

| tumu | stupid, thick |

| wenfo | new |

| yompe | old, former, previous |

| cùa | east, dawn, sunrise |

| día | west, dusk, sundown |

| bene | right, positive |

| komo | left, negative |

..

(Of course you can always use a periphrastic expression if you wanted.)

... 54 of which serve as transitive verbs

..

| boʒi | better | kegu | worse | bozor | he/she improves | kegor | he/she made something worse | boʒido | to improve | kegudo | to made worse |

| faizai | richer | paugau | blander | faizor | she developed | paugau | she run something down | faizaido | to enrich/develope | paugaudo | to run down |

| maze | open | nago | closed | mazori | he opens | nagori | he closes | mazedo | to open | nagodo | to shut |

| saco | fast | gade | slow | sacori | she speeds up | gadori | she slows down | sacodo | to accelerate | gadedo | to decelerate |

| fazeu | empty | pagoi | full | fazor | he empties | pagor | he fills | fazedo | to empty | pagodo | to fill |

| hauʔe | beautiful | ʔaiho | ugly | hauʔor | she beautifies | ʔaihor | she makes ugly | hauʔedo | beautify | ʔaihodo | to make ugly |

| ailia | neat | aulua | untidy | ailor | he tidies up | aulor | he messes up | ailido | to tidy up | auludo | to mess up |

| joga | wide | teza | narrow | jogor | he widens | tezor | he narrows | jogado | to broaden | tezado | to narrow |

| ái | white | àu | black | aidor | he whitened | audor | he turned something black | aido | to whiten | audo | to blacken |

| hái | high | ʔàu | low | haidor | she raised | ʔaudor | she lowered | haido | to raise | ʔaudo | to lower |

| guboi | deep | sikeu | shallow | gubodor | she deepens | sikedor | she makes shallow | gubodo | to deepen | sikedo | to make shallow |

| seltia | bright | goljua | dim | seltidor | he brightens | goljudor | he dims | seltido | to brighten | goljudo | to dim |

| taiti | tight | jauju | loose | taitidor | she tightens | jaujudor | she loosens | taitido | to tighten | jaujudo | to loosen |

| jutu | big | tiji | small | jutudor | he expands | tijidor | he shrinks | jutudo | to enlarge | tijido | to shrink |

| felgi | hot | polzu | cold | felgidor | she heats up | polzudor | she cools down | felgido | to heat up | polzudo | to cool down |

| baga | simple | kaza | complex | bagador | she simplifies | kazador | she complicates | bagado | simplify | kazado | to complicate |

| naike | sharp | maubo | blunt | naikedor | he sharpens | maubodor | he blunts something | naikedo | to sharpen | maubodo | to blunt |

| nucoi | wet | mideu | dry | nucodor | she makes wet | midedor | she dries | nucodo | to make wet | midedo | to dry |

| wobua | heavy | yekia | light | wobudor | he loads up | yekidor | he unloads | wobudo | to load up | yekido | to unload |

| pujia | thin | fitua | thick | pujidor | he makes thin | fitudor | he thickens | pujido | to make thin | fitudo | to thicken |

| yubau | strong | wikai | weak | yubador | she strengthens | wikador | she weakens | yubado | to strengthen | wikado | to weaken |

| fuje | soft | pito | hard | fujedor | softens | pitodor | she hardens | fujedo | to soften | pitodo | to harden |

| gelbu | rough | solki | smooth | gelbudor | she roughens | solkidor | she smoothes | gelbudo | to roughen | solkido | to smooth |

| ʔoica | clear | heuda | hazy | ʔoicador | she explains | heudador | she confuses | ʔoicado | to explain | heudado | to muddy the waters |

| selce | sparce | goldo | dense | selcedor | he prunes | goldodor | he intensifies | selcedo | to prune | goldodo | to intensify |

| cadai | fragrant | dacau | stinking | cadador | she make fragrant | dacador | she makes stinky | cadado | to make fragrant | dacado | to make stinky |

| detia | elegant | cojua | crude | detidor | he decorates/embellishes | cojudor | he spoils | detido | to decorate | cojudo | to decorate in a gauche style |

..

The top 4 adjectives in the table above are actually irregular comparatives.

The standard method for forming the comparative and superlative is ... ái = white : aige = whiter : aimo = whitest

..

However not quite all antonyms fall into the above pattern. For example ...

loŋga = tall, tìa = short

wazbia = far, mùa = near ... wazbo = distance, wazbai = about 3,680 mtr (the unit of distance)

..

..... Quantity

... many, a lot

..

haì = many

haì bawa = many men

This word is only used with countable nouns. With un-countable nouns we use hè.

hè comes after the noun that it qualifies.

moze hè = a lot of water

hè also can qualify verbs and adjectives. As with normal adverbs, if it doesn't immediately follow the verb it must take the form hewe.

glá doikori hè = the woman has walked a lot

glá (rò) hauʔe hè = the woman is very beautiful

hewe glá doikori = the woman has walked a lot

..

... few, a little, a bit a little bit

..

uhai = few

uhe = a little

However a word meaning the same as uhe is iyo (also iyowe, when used as an adverb separated from the verb). iyo occurs twice as much as uhe.

hemai = amount, quantity .... there is no word *haimai

..

... to a greater degree

..

Appended to an adjective, ge indicates to a greater degree.

Appended to an adjective, mo indicates to the greatest degree.

When we have this sort of construction, we are usually comparing to people or things. The background person or thing has the pilana wo. For example ....

jene jutuge jonowo = Jane is bigger than John

jene jutumo = Jane is biggest

Note ... In English the words "more" (also "most", "less" and "least") can occur with multi-syllable adjectives. Also "more" can qualify nouns and verbs as well. The béu equivalent of "more" when qualifying nouns (non-countable) and verbs is hege. haige is used for countable nouns.

[ haige would translate Thai " ììk ", as in " ììk nɯɯŋ bìa " ]

..

... to a less degree

..

Also we have zo which indicates a lesser degree.

Plus we have zmo which indicated the least degree.

However the above two suffixes don't appear that often. The most common adjectives have polar forms. And it is usual to switch to the form which will allow you to express yourself using the ge or the mo suffix. But here is an example from an adjective that doesn't have a polar form.

dè mutuzo = that one is not so important

dí mutuzmo = this one is the least important

..

... to the same degree

..

As well as ge, mo, zo and zmo there is one more suffix that is appended to adjectives. It is la (note this is a pilana when appended to nouns)

jene jutula jonowo = Jane is as big as John

..

... Antonym phonetic correspondence

..

In the above lists, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning from each other. However in béu there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | ai | |||

| f | e | |||

| b | eu | |||

| g | u | |||

| d | ua | high tone | ||

| l | =========================== | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ia | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | i | |||

| k | oi | |||

| p | o | |||

| t | au | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

Note ... The original idea of having a regular correspondence between the two poles of a antonym pair came from an earlier idea for the script. In this early script, the first 8 consonants had the same shape as the last 8 consonants but turned 180˚. And in actual fact the two poles of a antonym pair mapped into each other under a 180˚ turn.

An adjectives is called moizana in béu .... NO NO NO

moizu = attribute, characteristic, feature

And following the way béu works, if there is an action that can be associated with noun (in any way at all), that noun can be co-opted to work as an verb.

Hence moizori = he/she described, he/she characterized, he/she specified ... moizus = the noun corresponding to the verb on the left

moizo = a specification, a characteristic asked for ... moizoi = specifications ... moizana = things that describe, things that specify

nandau moizana = an adjective, but of course, especially in books about grammar, this is truncated to simply moizana

..

..... Adverbs

There are 4 types of word that function as adverbs in béu.

1) There are adjectives which are changed into adverbs by suffixing -we. For example ...

saco = quick

sacowe = quickly

THIS type of adverbs can have any position within a sentence. However if they immediately follow the verb which they are qualifying, the suffix is deleted. For example ...

doikora saco namboye = doikora namboye sacowe = sacowe doikora namboye = she is walking quickly home

2) There are nouns which are changed into adverbs by suffixing -we. For example ...

deuta = soldier

deutɘwe = "in the manner of a soldier"

Note that the final vowel in deuta changes here. This is because as well as being a suffix, wé is a noun in its own right meaning "way" or "method" (see the section on word building)

Just as saco is an adjective which is considered an adverb when immediately following a verb, so deutɘwe is an adverb that is considered an adjective when immediately following a noun.

Also a noun is formed by suffixing -mi to the end.

deutɘwemi = soldierliness

3) One of the functions of a nouns with pilana 1 => 8 + 15 is as an adverb. This type of adverb must follow the verb immediately. In a similar manner to type 2), if this form comes after a noun it is considered an adjective. For example ...

moŋgos flora ama pazbamau (the gibbon is eating an apple on the apple) pazbamau is an adjective describing where the apple is (or was).

moŋgos flora pazbamau ama (the gibbon is eating an apple on the apple) pazbamau is an adverb describing where the "eating" is taking place.

Note ... In English, the sentence "the monkey eats the apple on the table" is ambiguous.

Go thru the other pilana ???

4) This type of adverbs are nouns that are stand for time periods. For example tomorrow, yesterday, the past et. etc. Basically when they are not copula subjects, copula complements or in the ergative case, they are adverbs.

5) Words such as "often" ??? ( = many times ???) ... a particle ???

..

..... Signage

... Road

..

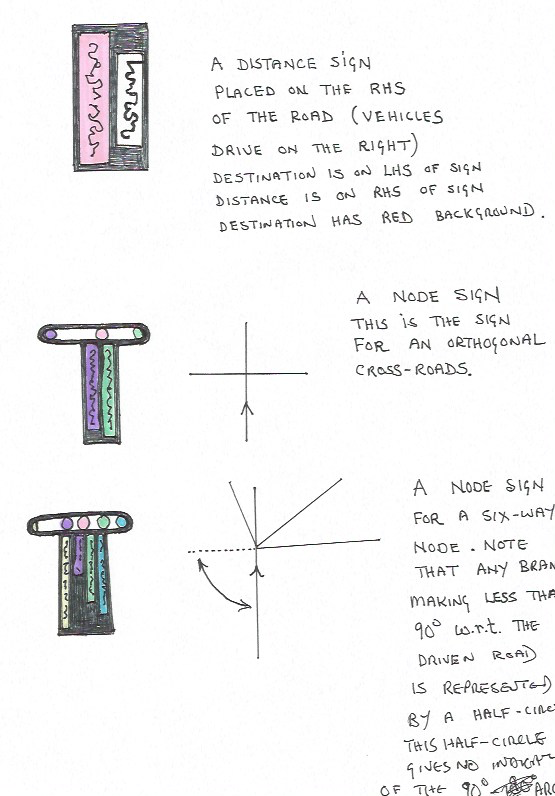

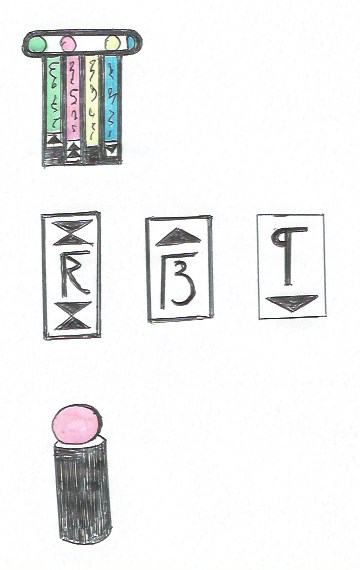

The above is what you pass through when you enter a town. There can be no "Welcome to Pleasantsville" written. It should just be a plane red colour on top. The name of the town on the sides.

On the opposite side of this sign, the red colour will be green. There will be nothing at all written anywhere on the other side ... next town ???

..

... Major Buildings

..

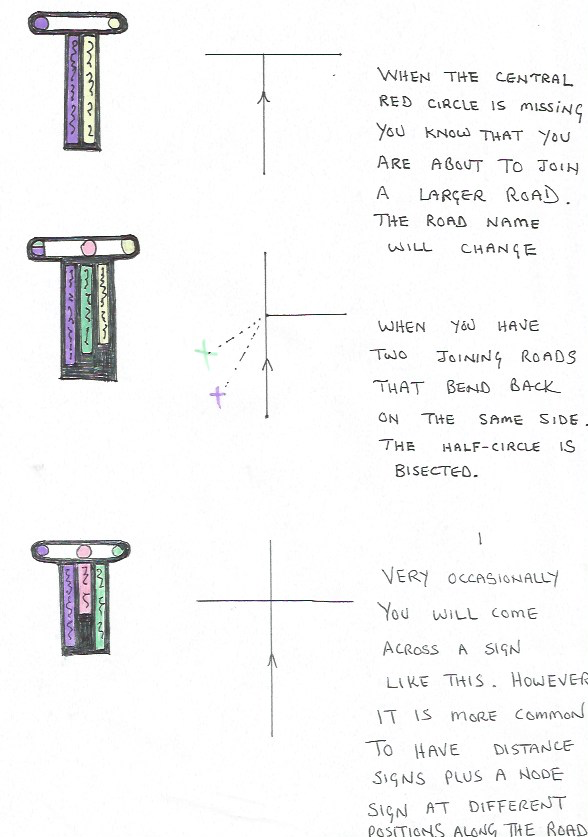

Quite similar to the node sign for roads is the sign giving directions in major buildings (such as airports, train stations etc.). However the position of the coloured circles does not show the angle that the joining road takes at the intersection. It shows the angle from the reader to the destination beacon. Actually there is a big black ring on the floor and it is assumed that the reader is within this ring. It is the angle from this ring to the destination beacon that is represented by the position of the coloured circles.

At the bottom of the below diagram, can be seen the destination beacon. It is a sphere about 50 cm in diameter. It is supported by a black pillar which is about 6 foot high. The beacon colour follows the colour of the circle in the sign. The beacon should be located in a clear (unobstructed) area maybe about 20 or 30 mtrs from the destination (for example toilets, information desk, screens displaying timetables, passport control etc. etc.). For course the destination should be clearly visible from near the beacon.

The signs at the middle of the above diagram are found near stairways and escalators. Upon stepping off a stairway the sign on the LHS should be clearly visible. This shows what floor you are on (ground floor is floor one by the way). The other two signs are positioned near the entrance to a stairway and tell you where the stairway is going.

..

... Streets

..

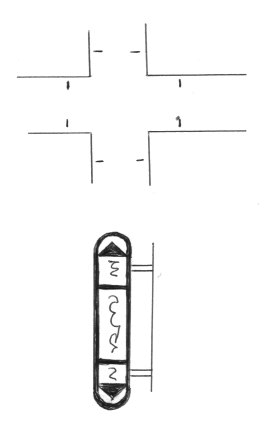

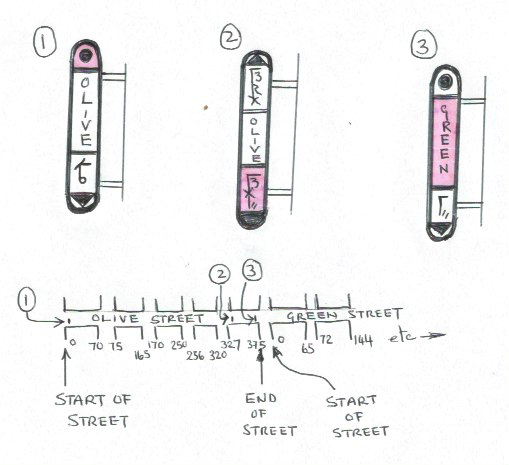

Above can be seen a street sign. These street signs are placed in from the corner, a distance equal to half the width of the street (measured building wall to building wall). They are well above head hight and offset from the wall by 60 % of their width. In the middle section is written the name of the street.

In the top section there is the distance along the street of the nearest corner. In the bottom section is the distance along the street of the next corner (measured in units of 2.13 mtrs ... houses do not have numbers as such ... they are all addressed as to how many mtrs they are along the street). Now the sign shown is what you see looking from the corner towards the street. What is written on the back side of the sign is exactly the same as you would see if you looked over directly behind you and saw the sign across the street (i.e. at an intersection you will see eight signs, but they come in pairs that are exactly the same).

One side of the street will have negative numbers. If you are walking away from the centre of town, then the negative numbered side will be on your left. If you are walking around the centre in an anti-clockwise direction, then the negative numbers will be on your left.

The start of the street is marked will the symbol for zero (a black dot), and no black triangle.

The end of the street is marked by that part of the sign having a red background (and no triangle).

To try and give you an idea of the system, I have drawn the diagram above. The signs 1, 2 and 3 are what you see on "olive street" at positions 1, 2 and 3.

What I have shown as pink should actually be red. I have done a bad drawing. Every instance of "olive" should be the exact same size. A lot of the signs will be different heights as no blank spaces are allowed inside a sign. Only one font and font size are allowed for every sign in a town.

One further point. If you are walking from the centre of town, and the street you are on is within 18 degrees of directly out from the centre, then every street name you see will have a green background (However the red background has precedence when green and red both apply).

No street can be longer than 1,872 units long (about 4 km)

..

..... Symbols

..

Words are not always written out in full. Certain common words have their own special symbol. For instance the ergative pronouns ...

And the non-ergative pronouns ...

The words "table" = pazba, "bracket" = gizgi, "interior wall" = ozdo and "chair" = yuzlu have probably got some relationship with the above symbols.

And the determiners ...

Note that dè looks similar to the sign for dùa ... similar but not exactly the same. The two slanting strokes meet the vertical stroke exactly halfway along for dè.

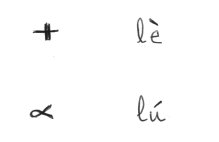

And the particles lè "and" and lú "or" ...

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences