Béu : Chapter 2 : The Verb

..... The 4 verb forms

... The infinitive verb form

..

The infinitive is called the hipe

The most common multi-syllable verbs end in "a".

The less common multi-syllable verbs end in "e" or "o".

The least common multi-syllable verbs end in "au", "oi", "eu" or "ai".

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk

The infinitive can be regarded as a noun.

..

... The indicative verb form

..

The indicative is called the hukəpe*

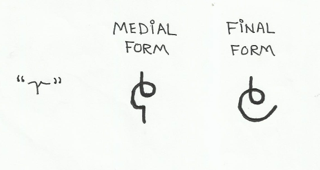

But first we must introduce a new letter.

..

..

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the hukəpe.

So if you hear "r", you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

1) First the final vowel is deleted from the infinitive.

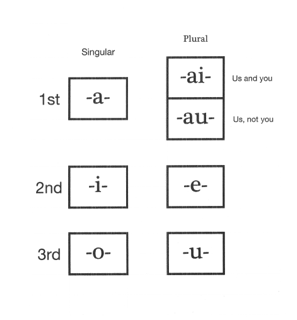

2) Then one of the 7 vowels below is added. These show person and number.

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikir = you walk

etc. etc. etc.

..

.. Tense

..

In béu tense is usually shown not on the verb but is indicated by an adverb of time. This adverb can come anywhere in a clause but it has a strong tendency to come clause initial.

YESTERDAY = yesterday I cleaned my car

THE DAY BEFORE YESTERDAY = the day before yesterday I cleaned my car

?? = I clean my car ... taken as a habitual in this case

TOMORROW = tomorrow I will clean my car

The words taiku meaning the past can be used instead of yesterday, the day before yesterday etc etc ??. This construction is equivalent to a past tense.

The words jauku meaning the future can simply be substituted for tomorrow ??. This construction is equivalent to a future tense.

To indicate the future, if the subject is human, often the word INTEND ??? is used. For example ... ??

Actually there is one tense in béu : the present tense which is shown by adding an "a". For example ...

doikara = I am walking

This tense is only used if the act is happening at the time of speaking. In contradistinction the English "-ing" suffix can turn up in time frames other than "now".

..

.. Aspect

..

The perfect aspect is shown by adding an "i". For example ...

doikari = I have walked

The ending "u" can be considered the opposite of the above aspect. Lets call it the "not yet" aspect. For example ...

doikaru = I have not yet walked / I have not walked

If you have plain doikar it will often be judged to have "habitual" aspect. This of course depends a lot on the context in which doikar occurs**.

The negative of the doikar form is doikarju

The -ra is only used for actions happening at the time of speaking. In English, the "to be - ing" construction is used for this. However the English "to be - ing" construction is also used to fit one action inside another. For example "she came in when I was shaving" ... usually set in the past but in the future is also possible. This is called the imperfect aspect (I think). In béu you use the copula plus the infinitive with the -n pilana affixed. For example ...

por kyu tar SHAVEn ... ( Side Note ... In this example, SHAVE is in what is uaually called the "imperfective" in the Western Linguistic Tradition, a form that combines tense and aspect)

Note ... SHAVEn is similar to an adjective in that it follows the copula. However it differs from an adjective in an important way ... it can never be an attribute of a noun. The form SHAVEana is the noun attribute.

...............XXX colour light green ................................

Note ... When you have the endings -ora, -ori and -oru they are always shortened to just -ra, -ri and -ru, provided the final consonant of the infinitive is not w y h or ʔ. For example ...

doikri = he has walked

...............XXX colour light green ................................

*The symbol for "r" is called huka (meaning "hook"). The word hukəpe actually means "R-form" by the normal rules of word building (mepe means form/shape).

**Different verbs have different likelihoods of being adjudged "habitual" when ending in "r". This likelihood is totally due to the internal semantics of the individual verb (which of course determine in which situations it is permissible to use the verb). ..

.. Negativeness

..

The indicative mood is negativized by adding ju. For example ...

doikarju = I do not walk

The present tense is negativized as above but with addition of the word kyu.i ( meaning "now"). For example ...

doikarju kyu.i = I am not walking

Note - the "u" aspect can be considered the negative of the "i" aspect and vice versa.

..

.. Probability

..

There are two adverbs màs and lói.

As with all adverbs they can be placed almost anywhere in a sentence. However these two have a strong preference to be sentence initial.

màs doikori = maybe he has walked

lòi doikori = probably he has walked

You could say that the first one indicates about 50 % certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty.

..

... The subjunctive verb form

..

The subjunctive is called the sudəpe

The subjunctive verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "s". That is all. For example ...

doikos = go on, let him walk.

The usage of the béu subjunctive covers the same functions as the Swahili subjunctive.

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding ke. For example ...

doikoske = best not to let him walk.

..

... The imperative verb form

..

The imperative is called the yeməpe

This is used for giving orders. When you utter an imperative you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action (although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible).

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

1) First the final vowel of the infinitive is deleted.

2) Then either -iya or -eya is added. iya when commanding one person, eya when commanding more than one person. For example ...

doikiya = walk !

For monosyllabic verbs ...

1) -ya is added. For example ...

dó = to do

doya = do it !

The negative imperative is formed by putting the particle kyà before the infinitive.

kyà doika = Don't walk !

There is no distinction for number in the negative imperative.

..

... The consecutive and simultaneous tenses

..

TO BE PLACED 2 CHAPTERS BEHIND THE ABOVE ARTICLE

Earlier we mentioned the present tense. There are 2 further tenses in béu. However they aren't relative to NOW but relative to the last ROGER form verb.

The consecutive tense, eu, shows that the action takes place after the time of occurrence of the previous ROGER form verb. For example ...

jana doikar moʒi solbeu = Yesterday I had a walk and then drank some water

The simultaneous tense, ai, shows that the action takes place at the same time as the previous ROGER form verb. For example ...

jana doikar moʒi solbeu = Yesterday I walked about a bit while drinking water

Note ... verbs with these endings, even tho', they are in indicative mood, actually have the mood of the initial verb ???

..

..... Short verb

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an indicative, subjunctive or imperative verb form is to delete the final vowel from the infinitive. However this is only applicable for multi-syllabe words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different.

For a monosyllabic verbs the indicative endings and subjunctive suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive. For example ...

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ... swo.uske = lest they fear ...... etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ... etc. etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ... etc. etc.

dàu = to arrive

cái = to depart

..

The above is the general rules for short verbs, however the 37 short verbs below the rules are different.

Their vowels of the infinitive are completely deleted for the indicative and subjunctive verb forms. For example ...

myàr gì = I love you ........................ not * mye.ar gì

pòr nambo = he enters the house ... not *poi.or nambo

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to like, to love | ||

| yái = to have | |||

| jòi = to go | jwèu = to suffice, to be enough | ||

| fà = to know | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

| bái = to ascend | byó = to be able to | blèu = to hold | bwá = to exit |

| gàu = to descend | glà = to store | gwói = to pass | |

| dó = to do | dwé = to come | ||

| lái = to change | |||

| cài = to use | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slè = to be under weak obligation | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kó = to see | kyò = to show | klói = to think | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyói = to be under strong obligation | plèu = to follow | |

| tèu = to put | twé = to meet | ||

| wàu = to lack | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to be good |

The imperative suffix is -ya for singular and plural for all short verbs. For example ...

nyauya nambo = go home !

swoya = fear !

gaiya = be in pain !

ʔauya ʃì = take it !

Some nouns related to the above ... yaivan = possessions, property, flovan = food, dovan = products, nauvan = gifts, glavan = reserves, dó = things that must be done, dwái = deeds, acts, actions, behaviour.

A particle related to the above ... yú ... a particle that indicates possession, occurs after the "possessed" and before the "possessor.

..

..... The copula

..

There is one copula in beuba.

Its infinitive is sàu. Following the method of other verbs, its negative is jù sàu.

The indicative mood is derived from the infinitive in the usual method. So ...

sàr = I am

ʃìr = you are

sòr = he/she/it is

etc. etc.etc.

The negative is formed be suffixing -ke. For example ...

sorke = he/she/it is not

Actually the (present tense, positive) copula is usually dropped if there is no chance of a misunderstanding.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... ʃirke moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... sàr moltai = I AM a doctor

Another situation where the (present tense, positive) copula tends to be used is when either the subject or the copula complement are longish trains of words. For example ...

solbua alkyo ʔá dori sùr sawoi = Those alcoholic drinks that she has made are delicious.

Unlike the other verbs, the copula has a different form for the past tense and a different form for the future tense. These are ...

tàr = I was

jàr = I will be

jarke = I won't be

etc. etc.etc.

(You could say that taiku sàr => tàr and jauku sàr => jàr)

The forms ‘’’sor’’’ and ‘’’sur’’’ are invariably shortened to simply -‘’’r’’’ and stuck on to the end of the copula subject. ........................................XXX colour light green ................................

Similarly the forms ‘’’sorke’’’ and ‘’’surke’’’ are invariably shortened to simply -‘’’rke’’’ and stuck on to the end of the copula subject. ...............XXX colour light green ................................

Note ... In copular sentences there is not free word order. They must be "copula subject" followed by "copula" followed by "object". Copula subject does not take the ergative suffix -s.

The subjunctive forms are ...

sas and saske ... uses ???

There are only two imperative forms ... jiya and jeya

In a later chapter ...

tari = I was already

taru = I was not yet

sari = I am already

saru = I am not yet

jari = I will be already

jaru = I will not yet be

There are 2 more words that might be considered copulaa ...

1) twài = to be located, to be placed .... perhaps an eroded form of a participle of tèu "to place"

2) yór = to exist ... a third person indicative form of the verb yái "to have". The third person indicative meaning is completely bleached in this usage.

..

..... Verb Chains

..

When 2 (or more) actions are considered inextricably tangled up in each other, béu forms a verb chain.

In a verb chain, usually the "most surprising" (i.e. the verb that conveys the most information) comes first and takes the normal ending (i.e. infinitive, indicative, subjunctive or imperative). If all the verbs in the verb chain are contiguous, then the remaining verbs are in the infinitive form. However if the non-final verbs in a chain are separated from the main verb, then it takes a different form. This form is called the iape. For the iape delete the final verb of the infinitive and add -ia for monosyllables and -i for non-monosyllables.

Verb chain rules ...

1) When two (or more) infinitives come together, they are considered verb chains.

2) A verb chain can only have one subject. *

3) When one verb is separated from the first one(s) it must take the special "chain" form.

4) Always the initial verb, takes the indicative, subjunctive and imperative verb forms, thus setting the mood for the entire chain. The following verbs are ...

if following the initial verb => infinitives ... hipe

if separated from the initial verb => iape

For example ...

joske pòi nambo = let's not let him go into the house ... there are 2 verbs in this chain ... jòi and pòi

jaŋkora bwá nambo dwía = he is running out the house (towards us) ... there are 3 verbs in this chain ... jaŋka, bwá and dwé

doikaya gàu pòi nambo jìa = Walk (command) down into the house (we are in the house) ... there are 4 verbs in this chain ... doika, gàu, pòi and jòi

Extensive use is made of serial verb constructions (SVC's). You can spot a SVC when you have a verb immediately followed (i.e. no pause and no particle) by another verb. Usually a SVC has two verbs but occasionally you will come across one with three verbs.

*Well maybe not always. For example jompa gàu means "rub down" or "erode". Now this can be a transitive verb or an intransitive verb. For example ...

1) The river erodes the stone

2) The stone erodes

With the transitive situation, the "river" is in no way going down, it is the stone. Cases where one of the verbs in a verb chain can have a different subject are limited to verbs such as erode (at least I think that now ??). Also the verbal noun for jompa gàu is not formed in the usual way for word building. Erosion = gaujompa

gaujompa or gajompa a verb in its own right ... I suppose that this would happen given time ??

I work as a translator ??? ... I work sàu translator ??

"want" ... "intend" ... etc. etc. are never part of verb chains ??

..

.. Balanced

..

For example ...

1) YESTERDAY FISH CATCHur poʔi flìa = Yesterday they caught some fish, cooked the fish and then ate the fish.

2) ALL AFTERNOON kludari REPORT ANSWERi PHONE = All afternoon I was writing reports and answering the telephone.

3) ALL EVENING solbair CHAMPAIGN flìa CAVIAR = All day we were drinking champaign and eating caviar.

The internal time structure of the chain must be worked out from knowledge of the situation described. The above sentences have the following time frames ...

1) The actions were probably one after the other. That is some catching occurred, followed by some cooking followed by some eating.

2) The actions here are not simultaneous but interspersed randomly throughout the afternoon.

3) The actions here could be interspersed randomly, but also could be overlapping somewhat.

..

.. Unbalanced

..

Now all the above were examples of "one off" or "balanced" verb chains ( "balanced" in the sense that all the verbs have about the same likelihood ). A more common type of verb chain is one in which some common verb is appended to a clause to give some extra information. Examples of these verbs are ... "enter", "exit", "cross", "follow", "to go through", "come", "go", etc. etc. etc.

..

. enter and exit

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the main verb. They are used where "into" and "out of" are used in English.

pòi = to enter

bwá = to exit

nambo bwá dwé = to come out of the house

nambo pòi jòi = to go into the house

nambo pòi dwé = to come into the house

nambo bwá jòi = to go out of the house

bwá nambo dwía = to come out of a house

pòi nambo jìa = to go into a house

pòi nambo dwía = to come into a house

bwá nambo jìa = to go out of a house

nambo bwá jaŋka dwé = to run out the house (towards us)

bwá nambo jaŋki dwía = to run out a house (towards us)

..

. across & along & through

..

When in verb chains, these 3 verbs tend to be the main verb.

kwèu = to cross, to go/come over

plèu = to follow, to go/come along

cwá = to go/come through

ROAD kwèu = to cross the road

ROAD kwèu doika = to walk across the road

kwèu ROAD doiki = to walk across a road

kwèu ROAD doiki dwía = to walk across a road (towards the speaker)

plèw and cwá follow the same pattern

Note ... some postpositions

road kwai = across the road = across a road

pintu cwai = through the door = along a road

Above are 2 postpositions ... derived from the participles kwewai and cwawai

ROAD plewai = along the road

..

. come and go

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the auxiliary verb.

Obviously they often occur as simple verbs.

"come", "go", "up" and "down" are often stuck on to the end of an utterance ... like a sort of afterthought. They give the utterance a bit more clarity ... a bit more resolution.

The below is nothing to do with verb chains, just a bit to do with the usage of dwé and jòi.

..

HERE------------>--------LONDON

londonye jòi = to go to London ... however if the destination immediately follows jòi -ye is dropped*. So ...

SIMILAR TO ADVERBS + GIVE ... LIGHT GREEN HI-LIGHT

jòi london = to go to London

jòi twè jono = to go to meet John

* In contradistinction, when a origin comes immediately after the verb dwé "to come" the pilana -fi is never dropped.

..

HERE----------<---------LONDON

dwé londonfi = to come from London

dwé jonovi = to come from John

..

. ascend and descend

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the auxiliary verb. They are used where "up" and "down" are used in English.

bía = to ascend

gùa = to descend

CLIMB ʔupai gìa = to climb down a tree

ʔupai CLIMB gìa = to climb down the tree

CLIMB ʔupai bía = to climb up a tree

THROW toili gìa = to throw down a book

These are also often inserted in verb chains to give extra information. The usually precede "come" and "go" when "come" and "go" are auxiliary verbs in the chain.

jòi gàu pòi nambo = to go down into the house

jaŋkora gàu pòi nambo jìa = he is running down into the house (away from us)

jaŋkora pòi nambo gìa dwía = he is running down into the house (towards us)

The two above sentences could describe the exact same event. However there is some slight connotation in the latter that the descending happened at the same time as the entering (i.e. the entrance of the house was sloping ... somewhat unusual)

..

. here and there

..

awata = to wonder

jaŋka awata = to run around

..

. bring and take

..

kli.o = a knife

kli.o ʔáu jòi = to take the knife away

kli.o ʔáu dwé = to bring the knife

ʔáu kli.o jìa = to take a knife away

kli.o ʔauya jòi náu jono = take the knife and go give to John

kli.o ʔauya dwé náu jono = bring the knife and give to John

If however the knife was already in the 2nd person's hand, you would say ...

dweya náu jono kli.o = come and give john the knife ... or ...

dweya náu kli.o jonoye = come and give the knife to john

Note ... the rules governing the 3 participants in a "giving", are exactly the same as English. Even to the fact that if you drop the participant you must include jowe which means away. For example ...

nari klogau tí jowe = I gave my shoes away.

Note ... In arithmetic ʔaujoi mean "to subtract" or "subtraction" : ledo means "to add" or "addition".

Note ... when somebody gives something "to themselves", tiye = must always be used, no matter its position.

..

. for and against

..

HELP = to help, assist, support

gompa = to hinder, to be against, to oppose

FIGHT = to fight

FIGHT jonotu = to fight with john ......... john is present and fighting

FIGHT HELP jono = to fight for John ... john is present but maybe not fighting

FIGHT jonoji = to fight for John ...........probably john not fighting and not present

FIGHT gompa jono = to fight against John

..

. to change

..

lái = to change

kwèu = to turn

lái sàu = to change into, to become

kwèu sàu = to turn into

The above 2 mean exactly the same

Note ...

paintori pintu nelau = he has painted a blue door

paintori pintu ʃìa nelau = he has painted a door blue

..

??? How does this mesh in with clauses starting with "want", "intend", "plan" etc. etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK BY DIXON ??

??? How does this mesh in with the concepts ...

"start", "stop", "to bodge", "to no affect", "scatter", "hurry", "to do accidentally" etc.etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK ON DYIRBAL BY DIXON

..

..... Numbers

..

béu uses base 12.

..

| one = | aja | 1012 = | ajau | 10012 = | ajai |

| two = | auva | 2012 = | uvau | 20012 = | uvai |

| three = | aiba | 3012 = | ibau | 30012 = | ibai |

| four = | uga | 4012 = | ugau | 40012 = | agai |

| five = | ida | 5012 = | idau | 50012 = | idai |

| six = | ela | 6012 = | ulau | 60012 = | ulai |

| seven = | oica | 7012 = | icau | 70012 = | icai |

| eight = | eza | 8012 = | ezau | 80012 = | ezai |

| nine = | oka | 9012 = | okau | 90012 = | okai |

| ten = | iapa | 10x12 = | apau | 10x12x12 = | apai |

| eleven = | uata | ............. 11x12 = | atau | ............. 11x12x12 = | atai |

You will noticed that 12 numbers over eleven have been shortened. For example the "regular" form for 20 would be auvau, but this is actually uvau.

Also the number 6, ela has been shortened. This would have been eula if everything was perfectly regular.

In the above table, 10 is actually, of course 12 : 90 is (9x12)+0 => 108 etc. etc.

The numbers in the above table combine, to express every number from 1 -> 1727 in one word. For example ;-

..

| 54312 | idaigauba |

| 50312 | idaiba |

| 64012 | ulaigau |

| 7212 | icauva |

| 612 | ela |

..

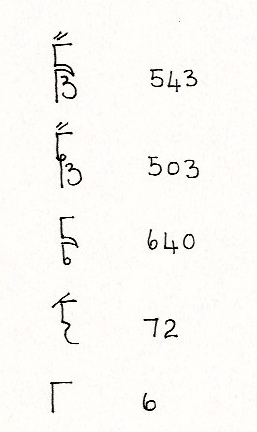

The above explains about the pronunciation of the numbers. But how are they written.

In fact the numbers are never written out in full. See below for the characters corresponding to the five numbers above.

..

..

It can be seen that all the vowels are dropped and there is a horizontal line inserted in the top right of the character. The symbol for h is used for inserting zeroes (although never pronounced).

If you had a leading zero you would use the word jù which is usually placed before nouns and means "space/empty/zero/no". 007 would be jù jù oica (three words)

To deal with a telephone number, you would lump the numbers in threes (any leading zero or zeroes by themselves though) and outspeak the numbers. If you were left with a single digit (say 4) it would be pronounced agai. If you were to pronounce it uga, it would of course mean 004. Also you would probably add the particle dù at the end. This means "exactly" (or it can mean the speaker has finished outspeaking the number)

..

To get an fractional number (regarded as specifiers ... as all numbers are) you just attach s- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| a unit | saja |

| a half | sauva |

| a third | saiba |

| a quarter | sida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of ??? plus the number.

These are fully numbers. They are written in the same way as numbers, except the have a squiggle above them. The squiggle looks like an "8" on its side that hasn't fully closed.

..

To get an ordinal number (regarded as adjectives) you just attach n- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| first | naja |

| second | nauva |

| third | naiba |

| fourth | nida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of nò plus the number.

These forms are adjectives 100% and are always written out in full.

..

To get (I don't know what these are called) (regarded as a noun) you just attach b- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| alone, single | baja |

| a double, a twosome, a duality | bauva |

| a threesome, a trinity | baiba |

| a foursome, a quartet | bida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

Note bajai = lonely

..

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of mebo plus the number.

..

And so ends chapter 1 ...

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences