Béu : Chapter 3

..... The R-form of the verb

..

Now we should introduce the active forms of the verb (also referred to as the R-form). béu has quite a comprehensive set of tense/aspect markers. The active form of the verb is built up from the infinitive form. There is only one infinitive in béu.

We will discuss the most-used form of the verb in this section, the R-form. But first we should introduce a new letter.

..

..

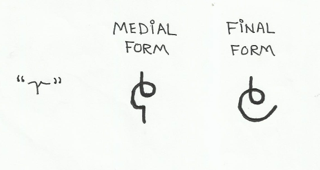

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the R-form of the verb.

So if you hear "r" or see the above symbol, you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause. (definition of a clause (semo) = that which has one "r" ... ??? )

O.K. ... the R-form is built up from the infinitive*.

1) First the final vowel is deleted.

*Excepts in rare cases (see "Adjectives and how they pervade other parts of speech")

..

... Slot 1

..

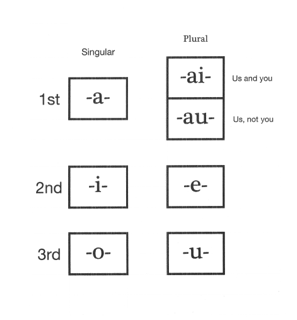

2) one of the 7 vowels below is added.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the Western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she). In the béu linguistic tradition they are called cenʔo-markers. (cenʔo = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play)

These markers represent the subject (the person that is performing the action). Whenever possible the pronoun that represents the subject is dropped, it is not needed because we have that information inside the verb with the cenʔo-markers.

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one must be used when the people performing the action included the speaker, the spoken to and possibly others. The lower one must be used when the people performing the action include the speaker, NOT the person spoken to and one or more 3rd persons.

Note that the ai form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

..

... Slot 2

..

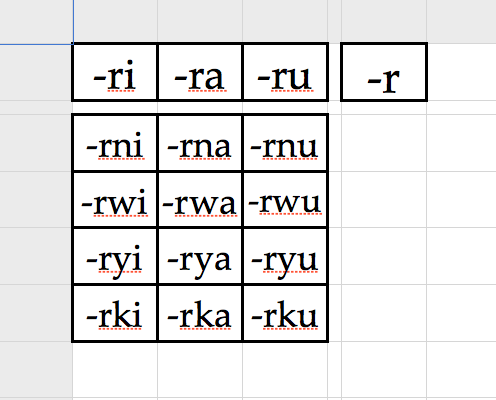

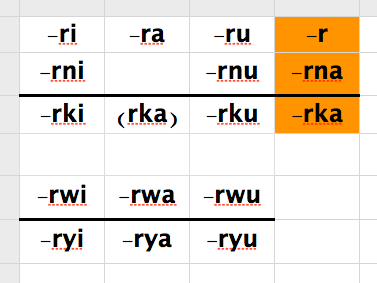

3) now one of the 16 markers shown below is added. 16 is quite a respectable number, as far as tense/aspect markers go.*

Now these markers represent what are called tense/aspect markers in the Western linguistic tradition. In the béu linguistic tradition, they are called gwomai or "modifications". (gwoma = to alter, to modify, to adjust, to change one attribute of something).

The table above has the gwoma arranged according to form. The two arrays below have the gwoma arranged according to meaning. The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have one entry enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a negative present tense negative you would express it periphrastically ... you would use the tenseless negative -rka followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Looking at the upper table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... i for the past, a for the present and u for the future.

-ri ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

-ra ... Should only be used if the action is happening NOW. English uses "to be xxxing". For example doikara = I am walking ... (doika = to walk)

-ru ... This is the future tense.

-r ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly".

The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school), Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). Actually in béu the pattern is broken a bit, in that -rna has NOTHING to do with the activity going on at the time of speech, it is actually a tenseless habitual. Also béu and English behave the same in the following way ... whereas by logic we should use doikarna in "I walk (to school everyday)", in fact doikar is used. doikarna would be used only if we were going on to MENTION some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift)

doikarna = "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use doikar

-rnu ... Now English doesn't have a future habitual. But if it did it would have a roll. For instance, suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In béu you would answer doikarnu.

The next row expresses the perfect tense.

While the perfect tense, logically this doesn't have that much difference from the past tense it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John. And think about the difference in meaning between "she has fallen in love" and "she fell in love" ... the first one means "she is in love" while the second one just talks about some of her history.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

Easy to translate into English ... doikorwi = He/she had walked ... doikorwa = He/she has walked ... doikorwu = He/she will have walked

The next row expresses the "not yet" tense.

Easy to translate into English ... doikoryi = He/she had not yet walked ... doikorya = He/she hasn't walked yet ... doikoryu = He/she will not have walked

Notice that the English translation, doikoryu is just the negative of doikorwu. Interesting eh ? In fact these two aspects can be in many ways regarded as the negatives of each other, although in English only the future tense gives the surface forms this way.

Which leads us on to the next row. This row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2 (that is right, row 2 does not have its own negative).

Just as -rna does not specify the present tense but instead gives a tenseless habitual, -rka gives a tenseless negative.

Easy to translate into English ... doikorki = He/she didn't walk ... doikorka = He/she doesn't walk ... doikorku = He/she will not walk

You may have noticed that the béu letter that negates verbs is very similar to the Chinese character that negates verbs (bù). This is pure coincidence.

By the way, the béu terms for the five aspects represented by these 5 rows are ... baga, dewe, pomo, fene, and liʒi.

*But even with 16 tense/aspect markers, not EVERY situation can be exactly expressed.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out" (using the progressive plus the perfect aspects). The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" (or working out over some period of time) to build up muscles. béu has no tense/aspect marker so appropriate.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

By the way, in the above example, the muscular schoolmate would use the r form of the verb plus the béu equivalent of "now", to explain his present condition. Good enough.

..

... Slot 3

..

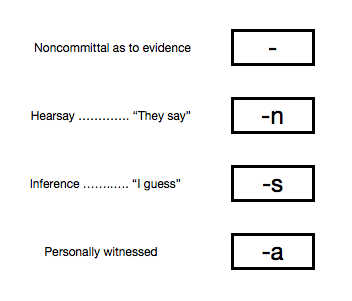

4) and finally one of the 4 teŋko-markers shown below is added.

teŋkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate" ... teŋko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. As evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In béu there are 4 evidential suffixes. One is what is called a zero suffix. And in meaning it gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based.

a) doikori = He/she walked ... this is neutral. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is saying what he is saying.

b) doikorin = They say he/she walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

c) doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow.

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The fourth tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

d) doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself".

This last teŋko can only be used with one of the gwomai . It can ONLY be used with the plain passed tense form i.

An o is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s".

..

..... Some valency changing operations

... Valency ... 1 => 2

..

The following words are about internal feelings. They are all configured the same way in béu.

It is hard to say whether the active verb (the first column) or the infinitive (the second column) is the base form. I guess we can consider them equally fundamental.

The third column gives a transitive infinitive (derived from the column two entry by infixing a -y-).

The fourth column gives an adjective of the transitive verb (derived from column three entry by affixing a -ana ... the active participle).

| ʔoime | to be happy, happyness | ʔoimora | he is happy | ʔoimye | to make happy | ʔoimyana | pleasant |

| heuno | to be sad/sadness | heunora | she's sad | heunyo | to make sad | heunyana | depressing |

| taudu | to be annoyed | taudora | he is annoyed | tauju | to annoy | taujana | annoying |

| swú | to be scared, fear | swora | she is afraid | swuya | to scare | swuyana | frightening, scary |

| canti | to be angry, anger | cantora | he is angry | canci | to make angry | cancana | really annoying |

| yodi | to be horny, lust | yodora | she is horny | yoji | to make horny | yojana | sexy, hot |

| gái | to ache, pain | gayora | he hurts | gaya | to hurt (something) | gayana | painful * |

| gwibe | to be ashamed/shame/shyness | gwibora | she is ashamed/shy | gwibye | to embarrass | gwibyana | embarrassing |

| doimoi | to be anxious, anxiety | doimora | he is anxious | doimyoi | to cause anxiety, to make anxious | doimyana | worrying |

| ʔica | to be jealous, jealousy | ʔicora | she is jealous | ʔicaya | to make jealous | ʔicayana | causing jealousy |

| .... | |||||||

| fàu | to know | fora | he knows | fayu | to tell | fayoru | she will tell |

..

The above shows is how to make an intransitive verb transitive.

It can be seen that it is normally formed by infixing -y-

When the final consonant is ʔ j c w or h the causative is formed by suffixing -ya

Also in short words, it is formed by suffixing -ya

Note ... when ya is added to a word ending in ai or oi, the final i is deleted.

Note ... when y is infixed behind t and d : ty => c and dy => j

Note ... All the verbs above are "state verbs". When state verbs are cited, the third person - present tense - no evidential form is used. Most verbs are "action verbs". When action verbs are cited, the third person - past tense - no evidential form is used. Also note that the infinitive of these state verbs, can in all cases be translated either as a noun or the noun form of an adjective.

Below is an example of this valency changing operation on an active verb.

doika = to walk

doikori = he walked

doikya = to run (as in "run a business")

doikyana = management

..

*You would describe a gallstone as gayana. However you would describe your leg as gaila (well provided you didn't have a chronic condition with your leg)

... Valency ... 2 => 1

..

The third and fourth columns show the passive forms.

The fifth column gives an adjective (derived from the column one entry by affixing a -wai ... the passive participle).

..

| kladau | to write | kladori | he wrote | kladwau | to be written | kladwori | It was written | kladwai | written |

| glói | to see | gloyori | she saw | gloiwa | to be seen | gloiwori | she was seen | gloiwai | seen |

| timpa | to hit | timpori | he hit | timpwa | to be hit | timpwori | he was hit | timpwai | hit |

| poʔau | to cook | poʔori | she cooked | poʔawa | to be cooked | poʔawori | it was cooked | poʔawai | cooked |

..

This is how to make a transitive verb passive. The subject of the active clause, can be included in the passive clause as an afterthought if required. It is added after the particle hí *

It can be seen that it is normally formed by infixing -w-

When the final consonant is ʔ y or h the passive is formed by suffixing -wa

Also in short words, it is formed by suffixing -wa

Note ... when wa is added to a word ending in au or eu, the final u is deleted.

Also note ... these operations can make consonant clusters which are not allowed in the base words. For example, in a root word -mpw- would not be allowed ( Chapter 1, Consonant clusters, Word medial)

..

*hí means "source" when it is not acting as a particle, introducing the agent in a passive clause.

..

... Concatenation of the valency changing derivations ... 1 => 2 => 1 and 2 => 1 => 2

..

| ʔoime | = to be happy | ʔoimye | = to make happy | ʔoimyewa | = "to be made to be happy" or, more simply "to be made happy |

..

| fàu | = to know | fa?? | = to tell | fa ?? | = |

..

| timpa | = to hit | timpawa | = to be hit | timpawaya | = to cause to be hit |

..

Semantically timpa is direct action (from agent to patient). Whereas timpawaya is indirect, possibly involving some third party between the agent and the patient and/or allowing some time to pass, between resolving on the action and the action being done unto the patient.

..

..... A discussion of English participles

..

Now English has two participles, the "active participle" and the "passive participle".

They appear as adjectives (of course, an adjective derived from a noun is the definition of "a participle"), however both forms also appear in verb phrases. If you are given a clause out of context it is sometimes impossible to tell if the participle is acting as an adjective or as part of a verb phrase. For example ... first the "active participle" ...

1) The writing man

2) The man is writing

3) The man is writing a book

In 1) "writing" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "writing" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The man is green a book" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "is writing" is a verb phrase (one that has given progressive meaning to the verb "write"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "is writing" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

... now the "passive participle" ...

1) The broken piano

2) The piano is broken

3) The piano was broken

4) The piano was broken by the monkey

In 1) and 2) "broken" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "broken" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 3) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 4) ... No not an adjective "The piano was green by the monkey" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 4) is that "was broken" is a verb phrase (one that has given passive meaning to the ambitransitive verb "break"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 3). The proper analysis of this could be that "was broken" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 3) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations* when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

*The five-week deadlock between striking Peugeot workers and their employer was broken yesterday when the management obtained a court order to end a 10-day sit-in at one of the two factories in eastern France, Sarah Lambert writes.

I would say either analysis is valid for the above sentence.

..

..... The béu participles

..

There are four participles in béu. They are known as plovai in the béu linguistic tradition.

A participle is an adjective that has been derived from a verb.

..

... the habitual participle

..

The habitual participle is formed by affixing -ana to the infinitive. For example ...

kludau = to write

kludana = habitually writing

and because of the strong tendency of adjectives to also serve as nouns ...

kludana = the one who is always writing => writer/author

..

... the passive participle

..

The passive participle is formed by affixing -wai to the infinitive. For example ...

kludau = to write

kludwai = written

and because of the strong tendency of adjectives to also serve as nouns ...

kludwai = the one that is written => a note

..

... the present participle

..

The present participle is formed by affixing -la to the infinitive. For example ...

kludau = to write

kludaula = writing at this moment => the one writing at this moment

..

... the future participle

..

The plain infinitive can be used to modify a noun

toili = book

toili kludau = the book that must be written

Notice that the meaning is "the book that SHOULD be written" rather than "the book that WILL be written"

Maybe the name "future participle" is not ideal ... never the less, it is called the future participle.

and because of the strong tendency of adjectives to also serve as nouns ...

kludau = that which must be written => an (school) assignment

..

... 8 co-ordinates

There are 6 suffixes, that when attached to a noun, make an adjective.

nambo = house

nambokoi = above the house

nambobeu = below the house

nambofia = this side of the house ... béu speakers, if a building is in side, prefer to specify a position w.r.t. their own position, and not to what is called "front" my convention.

nambopua = the far side of the house

namboʒi = to the left of the house

nambogu = to the right of the house

Also there are 2 suffixes, that when attached to an infinitive, make an adverb.

solbe = "to drink" or "drinking"

solbetai = before drinking

solbejau = after drinking

Now in an infinitive phrase the constituent order is Subject Object Infinitive, so ...

moze solbetai jonos CHECKED THE GLASS WAS CLEAN = Before drinking the water, John checked that the water glass was clean.

Also we have the constructions ...

moze solben jono KEPT AN EYE OUT FOR TIGERS = While drinking water, John kept an eye out for tigers.

jono moze solbewe I DRINK BEER = I drink beer like John drinks water

..... A bit about adverbs

If an adjective comes immediately after a verb (which it normally would) it is known to be an adverb. For example saco means "slow" but if it came immediately after a verb it would be translated as "slowly". However if we add -we to it so we get the form sacowe the adverb can move around the utterance ... wherever it wants to go.

Now going back to the 6 "co-ordinate" particles koi beu fia pua ʒi gu in the previous section. Basically a word ending in one of these particles, is an adjective. For example ...

yiŋkia haube = the beautiful girls

yiŋkia nambopua = the girls behind the house

However sometimes nambopua acts as an adverb. When it does so it must come directly after the verb (that is ... we can not add -we and move it from its position immediately behind the verb, as can be done with other adjectives active as adverbs). For example ...

yiŋkia nambopua lendura = the girls behind the house play

yiŋkia lendura nambopua = the girls play behind the house

..

-we can also be affixed to a noun and also produce an adverb. For example ;-

deuta means "soldier"

deutawe means "in the manner of a soldier"

as in doikora deutawe = he walk like a soldier

So that is basically all there is to adverbs. In the Western linguistic tradition many other words are classified as adverbs. Words such as "often" and "tomorrow" etc. etc.

In the béu linguistic tradition all these words are classified as particles, a hodge podge collection of words that do not fit into the classes of noun (N), adjective (A), verb (G) or adverb.

..

... Parenthesis

..

béu has two particles that indicate the start of some sort of parenthesis. In a similar way to a mathematical formula, where brackets mean that the arguments within the brackets should be evaluated first, the two béu particles indicate that the immediately following clause should be processed (by the brain) before arguments outside of the parenthesis are considered.

..

. tà ... the full clause particle

..

This is basically the same as "that" in English, when "that" introduces a complement clause. For example ...

"He said THAT he was not feeling well"

Notice that "he was not feeling well" is complete in itself, it is a self-contained clause.

..

. ʔà ... the gap clause particle

..

This is basically the same as "what" in English, in such sentences as ...

"WHAT you see is WHAT you get"*

Notice that "you see" and "you get" are not complete clauses, there is a "gap" in them.

The phase "WHAT you see", (to return to the mathematical analogy again) may be thought of as a "variable". in this case, the motivation for using a "variable", is to make the expression "general" rather than "specific". (Being general it is of course more worthy of our consideration). Other motivations for using a "variable" is that the actual argument is not known. Yet another is that even though the particular argument is known, it is really awkward to specify satisfactorily.

EXAMPLE

Another way to think about the ʔà construction, is to think of it as a "nominaliser", a particle that turns a whole clause into a noun. To use the example from just above ....

"see" is an intransitive verb with two arguments. To replace one of these arguments by ʔà is like defining the missing argument in terms of the rest of the clause i.e. it changes a clause into a constuction that refers to one argument of that clause.

. Gap clause particles in other languages

There is no generally agreed upon term for the type of construction which I am calling "gap clause" here. Dixon calls it a "fused relative", Greenberg calls it a "headless relative clause". I don't like either term. A fused relative implies that a generic noun (i.e. "thing" or "person") somehow got fused with a relativizer. This certainly never happened although this type of clause can be rewritten as a generic noun followed by a relativizer. As for "headless" relative clause ... well I think the type of clause that we are dealing with is in fact more fundamental then a relative clause, so I would not like to define it in terms of a relative clause.

My thoughts on this type of clause are ...

Well "what" was firstly a question word. So you have expressions like "Who fed the cat"

Then of course it is natural to have an answer like "I don't know who fed the cat"

Now the above sentence is similar to "I don't know French" or "I don't know Johnny".

Now you see the expression "who fed the cat" fills the slot usually occupied by a noun in an "I don't know" sentences.

So "who fed the cat" started to be thought of as a sort of noun.

Now from the "know (neg)" beachhead*, the usage would have spread to "know" and also the such words that have "knowing" as an essential part of their meaning. Words such as "remember", "report" etc. etc.

*I call "know (neg)" a "beachhead"**. A beachhead is a usage(and/or the act or situation behind that usage) that facilitates the meaning of a word to spread. Or the meaning of an expression to spread. A beachhead can be defined simply as an expression, but sometimes some background as to the speakers environment has to be given. For example suppose that one dialect of a language was using a word to mean "under", but this same word meant "between/among" in all other dialects. Now suppose you did some investigating and found that all other dialects of this language was spoken on the steppes and their speakers made a living by animal husbandry. However the group which diverged from the others had given up the nomadic life and settled down in a lush river valley. In this valley their main occupation was tending their fruit orchards.

It could be deduced that the change in meaning came about by people saying ... "Johnny is among the trees". Now as the trees were thick on the ground and had overspreading branches, this was reanalysed to mean "Johnny is under the trees". Hence I would say ...

The beachhead of word "x" = "between" to word "x" = "under" was the expression "among the trees" (and in this case a bit of background as to the "culture" of the speakers would be appropriate). ... OK ? ... understood ?

For an expressing to become a beachhead, it must, of course, be used regularly.

ASIDE ... I have thought about counting rosary beads as a possible beachhead that changed the meaning of "have", in Western Europe, from purely "possession" to a perfect marker. This is just (fairly ?) wild conjecture of course. (The beachhead expression being "I have x beads counted" with "counted" originally being a passive participle)

I am digressing here ... well to get back to "who fed the cat". We had it being considered a sort of noun. Presumably it was at one time put directly after a noun in apposition (presumably with a period of silence between the two) and qualified the noun. Then presumably they got bound closer together, the gap was lost, and this is the history of one form of relative clause in English.

**Actually I would have liked to use the term pivot here. However this term has already been taken.

From the dictionary

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 1. A position on an enemy shoreline captured by troops in advance of an invading force

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 2. A first achievement that opens the way for further developments.

There are 4 relativizers ... ʔá, ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja. (relativizer = ʔasemo-marker)

ʔasemo = relative clause.

It works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. The béu relativisers is ʔá. Though ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja also have roles as relativisers.

The main relativiser is ʔá and all the pilana can occur with it (well all the pilana except ʔe. ʔaí is used instead of * ʔaʔe).

The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its pilana on the suffixed to the relativizer. For example ;-

glà ʔá bwás timpori rà hauʔe = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful.

bwá ʔás timpori glà rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

The same thing happens with all the pilana. For example ;-

the basket ʔapi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ʔala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman ʔaye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town ʔafi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad ʔalya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

the boat ʔalfe you have just jumped is unsound

báu ʔás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

- nambo ʔaʔe she lives is the biggest in town.

báu ʔaho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife ʔatu he severed the branch is a 100 years old

báu ʔán dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police*

The old woman ʔaji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy ʔaco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

*Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. n marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause.

As you see in above, ʔa in the form * ʔaʔe is not allowed. Instead you must use ʔaí.

The use of ʔái and ʔàu as relativizers are basically the same as the use of "where" and "when" in English. These two can combine with two of the pilana.

?aifi = from where, whence

?aiye = to where, hence

?aufi = from when, since

?auye = to when, until

The use of ʔaja basically is a relativizer for an entire clause instead of just the noun which it follows.

For example ???????

WITH SPACE AND TIME

PLURAL FORM

..

... the NP with the present participle core ??

..

Now the phrase jono kludala toili is a noun phrase (NP) in which the adjective phrase (AP) qualifies the noun jono

(Notice that in the clause that corresponds to the above NP, jonos kludora toili (John is writing the book), jono has the ergative suffix and the 3 words can occur in any order : with the NP, jono does not take the ergative suffix and the 3 words must occur in the order shown.)

glói = to see

polo = Paul

timpa = to hit

jene = Jenny

glori polo timpala é = He saw paul hitting something

glori pà timpala ò = He saw me hitting her

glori hà (pás) timparwi ò = He saw that I had hit her

glori jene timpwala = He saw Jenny being hit

Now the question is where is this special NP used. Well it is used in situations where English would use a complement clause. For example with algo meaning "to think about",*

1) algara jono = I am thinking about John.

2) algara jono kludala toili = I am thinking about John writing a book.

Note ... According to Dixon, the standard English translation of 2) would be "I am thinking about John's writing a book" which I find quite strange even though English is my mother tongue. I have decided to call this sort of construction in béu a special kind of NP, while Dixon has called the equivalent expression in English the "-ing" type of complement clause. I think this is just a naming thing and doesn't really matter.

*"to think (that)" is alhu in béu. alhu also translates "to believe".

..

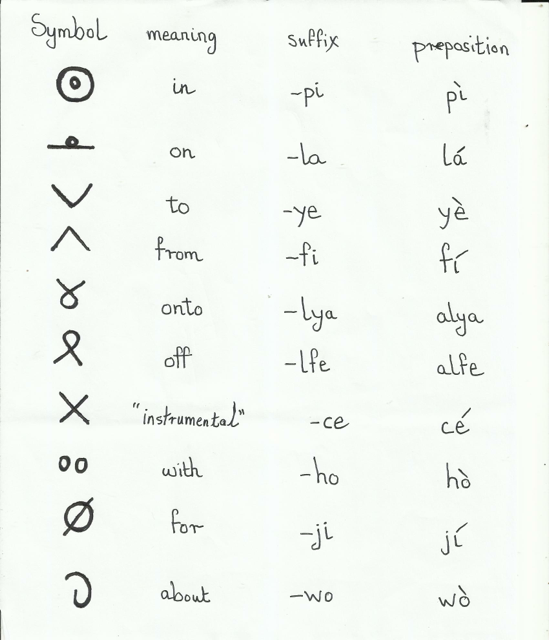

..... The pilana

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON are called "cases". The classical languages, Greek and Latin had 5 or 6 of these. Modern-day Finnish has about 15 (it depends on how you count them, 1 or 2 are slowly fading away). Present day English still has a relic of a once more extensive case system : most pronouns have two forms. For example ;- the third-person:singular:male pronoun is "he" if it represents "the doer", but "him" if it represents "the done to".

The 12 béu case markers are called pilana

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana <= (pila + ana), in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle". It is an adjective which means "putting (something) in position".

As béu adjectives freely convert to nouns*, it also means "that which puts (something) in position" or "the positioner".

Actually only a few of them live up to this name ... nevertheless the whole set of 12 are called pilana in the béu linguistic tradition.

..

..

The pilana are suffixed to nouns and specify the roll these nouns play within a clause.

As well as the 10 illustrated above, we have s for the ergative case and n for the locative case. Also we have the unmarked case which represents the S or O argument.

sá and nà are the free-standing variants of -s and -n.

The pilana specify the roll that a noun has within a clause. However both the ergative case and the locative case (and a few other cases) can specify what rolls a noun has within a NP.

For example nambo pàn = "a/the house at me" or "my house"

timpa báus glà = the man's hitting of the woman ... this is an example of an infinitive NP.

letter blicovi = the letter from the king

pen gila = a pen on your person

As shown above the pilana are represented by their own symbols. Or at least the ten that do not consist of single letters.

For the suffix form of the first 2 and last 2 symbols given above, the end of the word proper "touches" the symbol. For the other 6 symbols, the word proper "impinges" upon the symbol. See below ...

..

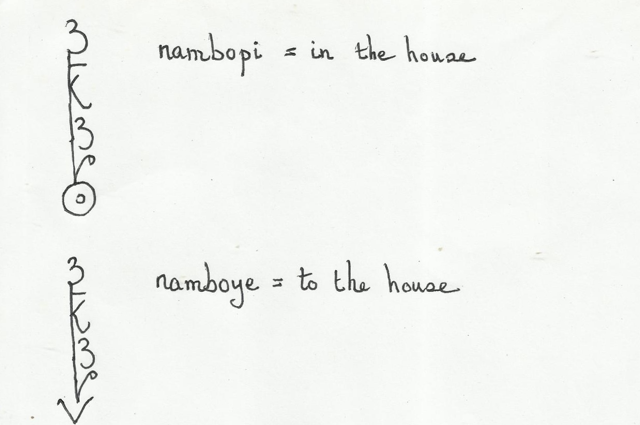

..... Rules governing the pilana

..

Now one quirk of béu (something that I haven't heard of happening in any natural language), is that the pilana is sometimes realised as an affix to the head of the NP, but sometimes as a preposition in front of the entire NP. This behaviour can be accounted for with thing with two rules.

1) The pilana attaches to the head and only to the head of the NP.

2) The NP is not allowed to be broken up by a pilana. The whole thing must be contiguous. So if a NP has elements after the head the case must be realised as a preposition and be placed in front of the entire noun phrase.

3) No two pilana can be stuck together (WOULD THIS EVER HAPPEN ??)

So if we have a NP with elements to the right of the head, then the pilana must become a preposition. The prepositional forms of the pilana are given on the above chart to the right. These free-standing particles are also written just using the symbols given on the above chart to the left. That is in writing they are shorn of their vowels as their affixed counter-parts are.

Here are some examples of the above rules ...

..

fanfa = horse

sonda = son

blico = king

fanfa sondan = the horse of the son

sonda blico = the son of the king

However the suffixed form can only be used if the genitive is a single word. Otherwise the particle na must be placed in front of the words that qualify. For example ;-

We can't say *fanfa sondan blicon however. The -n on sonda is splitting the NP sonda blico.

So we must say fanfa nà sonda blicon

Some more examples ...

fanfa nà sonda jini blicon = "the horse of the king's clever son

fanfa nà sonda nà blico somua = "the horse of the fat king's son"

..

Here are some more examples of the above rules ...

pintu nambo = the door of the house

pintu nà nambo tuju = the door of the big house

When one of the specifiers is involved we have two permissible arrangements.

1) pintu á nambon= the door of some house

2) pintu nà á nambo = the door of some house

1) is the more usual way to express "the door of some house", but 2) is also allowed as it doesn't break any of the rules.

This also goes for numbers as well as specifiers.

papa auva sondan = the father of two sons

papa nà auva sonda = the father of two sons

..

*Another case when the pilana must be expressed as a prepositions is when the noun ends in a constant. This happens very, very rarely but it is possible. For example toilwan is an adjective meaning "bookish". And in béu as adjectives can also act as nouns in certain positions, toilwan would also be a noun meaning "the bookworm". Another example is ʔokos which means "vowel".

The pilana and the relative clause

We have already seen that the final element of a NP can be a relative clause and we introduced the two particles à and às : corresponding to "who" and "whom".

Actually the basic relativizer is à and -s is the ergative case marker. The other case markers (well most of them) can also be suffixed to the à relativizer.

àn quite a common relativizer also.

Remember when we talked of the NP before we said a genitive (or a locative) can go as the last element in the adjective slot. For example ...

nambo jonon = John's house

However if the element that must become the genitive is longer than one word, the relativizer àn must be used. For example ...

nambo àn báu jutu = The big man's house.

WAIT ... HOW DOES THIS SQUARE UP WITH THERE BEING TWO FORMS OF THE "N" CASE .... SUFFIXING FORM AND FREE STANDING FORM ??

"the man ate the apple on the table" ... ambiguous in English

ALL THE BELOW SHOULD BE AFTER THE PILANA IS INTRODUCED

the basket api the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman aye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town avi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad à alya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.*<-sup>

the boat à alfe you have just jumped is unsound.*<-sup>

báu ás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

nambo àn she lives is the biggest in town.

Note ... The man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man that own dog that I shot, reported me to the police

báu aho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife age he severed the branch is a 100 years old

The old woman aji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy aco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

..

And so ends chapter 2 ...

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences