Béu : Chapter 5

The parish flags

béu country is divided into "parishes". These are rural communities of 10,000 -> 50,000 people (urban areas have are distinct from rural areas and have a very different administrative structure).

The parish boundaries follow geographical features, such as streams and ridges etc. However the shape of a parish approximates to a hexagon. In fact in a total featureless landscape it would be a hexagon.

The rim banners

Each parish has 6 banner-rows along its boundaries. A banner-row consists of 17 banners about 10 m apart. Each banner is made from a pole about the girth of an adults arm or leg. Each pole is about 7.5 m high and the top 5 m of the pole has an orange banner. The cloth of the banner is about 1/3 m wide. When about half the original cloth has been weathered away the cloth should be replaced, best to do an entire banner-row at on time. These banner-rows are normally placed in prominent positions. They can be anywhere along a boundary, but it isn't considered good to have the gap too small or too big between any neighbouring banner-rows.

In sparsely populated areas you get what is called a super-parish. They are around 10 times the size of a normal parish (but their population falls within the 10,000 -> 50,000 limit). These super-parishes have 2 barrier-rows per side(that is 12 in total), and each banner-row has 19 banners. All these banner dimensions are about 15% to 20% bigger than normal.

The outer banners

About 2/3 of the way out from the parish centre there are what are called the spoke banners arranged in banner-rows. There are 4 of these banner-rows and each has 11 banners. Again these are in prominent positions and/or well visible from roads. Again they should be quite spread out from each other.

Each of there banner-rows, instead of delineating the parish boundary, point towards the administrative centre of the parish, the toilido.

(For a super-parish there are 8 banner-rows with 13 banners each)

The inner banners

About 1/3 of the way out from the parish centre there are what are called the spoke banners arranged in banner-rows. There are 3 of these banner-rows and each has 5 banners. Below is what a banner looks like.

Again each of these banner-rows is pointing to the toilido.

(For a super-parish there are 5 banner-rows with 7 banners each)

The cremation oval

Below is shown a typical cremation oval. Typically they are placed in a wilderness area, maybe near the parish boundary. The platform is about 1.5 m high with steps all around. It has the shape of an oval, usually with the two sharp curves cut off. In the two foci we have two objects.

On the east side we have the kilo. It is a structure about 1.7 m high (standing on a plinth about .2 m high), which is in the shape of the Gherkin in London. Metal bands can be seen on its surface. Multifaceted with each facet made of a pink glass. It has a silver ball on top, about 15 inch in diameter.

On the west side we have the ulgu. It is a structure about 1.7 m high (standing on a plinth about .2 m high), which is in the opposite shape from the Gherkin in London. Metal bands can be seen on its surface. Multifaceted with each facet made of a purple/mauve glass. It has a golden ball on top, about 15 inch in diameter (its top side is jet black).

Six poles (called jomo) can be seen on the oval. These must be changed to suit every cremation. After a cremation they are left as they are, until the next cremation.

I have named them NM (north middle), NW (north west), SW (south west), SM (south middle), SE (south east) and NE (north east).

These jomo can have 1 of 4 types of head (shown below). From L => R, I have named these the empty head, single head, double head and multiple head.

A jomo is about 5 m high. The second and third tops are about 1.3 m high. The diameter of the 4th top is 2.1 m although on occasions this must be increased.

The jomo are made of varnished wood and are square in cross-section, 25 cm at the bottom, narrowing to 21 cm at the top. The 2 middle tops (see below) can be constructed from anything. However they should look solid and all faces should glow in the dark (not necessarily at the edges). The single and double heads gradually tapper to a point. They are square in cross-section, all the way to the point.

Basically the choice of head reflects the descendants that the deceased left behind. If the deceased had no living descendants at the time of death, then all the jomo have empty heads. This is a greyish/white sphere.

If the deceased has living descendants then the NM jomo will have a single head. This head represents the oldest child (legally recognised child). If the first born was male, this head will be orientated out of the oval, if female into the oval.

The second oldest child is also represented by a single head. If this child was male, the next empty jomo in a clockwise direction from the NM one receives a single head. If this child was female, the next empty jomo in a anti-clockwise direction thom the NM one receives a single head.

And so you do with the third, fourth, fifth and sixth child . If there are only six children, then yellow bunting is drapped from the "elbow" of the head, if this child was female. Blue bunting is drapped from the "elbow" of the head, if this child was female.

If there were seven children, then the last head placed should be a double head. Yellow or red bunting being drapped from the "elbows" depending upon the sex of the last two children born.

If there were eight or more children born to the deceased, then the last head placed should be a multiple head. Yellow or red bunting being drapped equip-distantly around the rim of the head to represent the sex of these children. In exceptional circumstances (when many, many children produced), the diameter of the multiple head has to be enlarged.

If any of these children have predeceased the deceased, then red bunting is draped from the "elbow" of the head representing them (if the elbow already has another colour of bunting, then the red bunting is intermixed with the yellow or blue bunting).

So now we have sorted out what heads we want and we have given the NM jomo head an orientation.

Now we give the other single heads an orientation (the double head is always orientated, so that you can see it best from where the deceased's head is). The multiple head has no orientation : it can spin.

The orientation of the other single heads depend upon the difference between the birthday of the first child and the child represented by that jomo. Here are two example to explain the system ...

1) The second oldest child is male. His birthday is exactly .4 months after the first born's. His head will be orientated 150 degrees anti-clockwise with respect to the first born's.

2) The tird oldest child is female. Her birthday is exactly 1 month after the first born's. Her head will be orientated 30 degrees clockwise with respect to the first born's. Note that male is anti-clockwise and female is clockwise.

Now we come to the tilting of the jomo. All jomo with a single head are tilted. The maximum tilt (that is the maximum deviation from the vertical) is 30 degrees.

To work out the tilt for every jomo we first must work out the "Index" for the deceased. The index is some amount between 0 and 1. The index is got from the graph above. The horizontal axis is age and the high of the plotted line at the age in which the deceased died, determines his index.

The plotted line is can be plotted (by using a certain formula) when A, B, C and D are known. A is a constant (= -9 months). B and C and D can be determined from the last 12 years of parish records. (By the way there are two graphs, one for each sex. And A and B and C are sex dependant.

Assuming the deceased is a male ...

B = the average age over the past 12 years in which the boys(young men) "mastered the laws".

C = the average age over the past 12 years in which the males married plus 18 years.

D = the average age of death for males over the past 12 years. No deaths that occur before "C", contribute to this average.

If the deceased is female, we determine our graph using the same formula, but now we have ...

B = the average age over the past 12 years in which the girls(young women) "mastered the laws".

C = the average age over the past 12 years in which the females married plus 30 years.

D = the average age of death for females over the past 12 years. No deaths that occur before "C", contribute to this average.

OK so now we have worked out the index for the deceased. Now each post with a single head is assigned a random number between 0 and 1.

The tilt of a post = Index x Random number x 30 degrees.

So this tilt is applied to the relevant post. The tilt follows the orientation of the head.

As can be imagined, every cremation involves a bit of work to have all the jomo at the correct orientation and tilt.

The field of rest

After the body has been cremated, the ashes are put in a box and interred in the "field of rest". The field of rest takes the form of many wide trenches dug in the ground. From above it looks like a maze. The "ash boxes" are deposited in either side of the trench. There are four rows these "ash boxes" deposited in each side of the "trench".

The parish hall

Below is shown the plan of the parish hall. This is the administrative centre of the parish and the place where the banner-rows point to.

The red shape at the top of the plan is the water-fountain. It must have a red tiled roof. It is to provide clean drinking water to passers by and also a sheltered place to rest. It can take a variety of forms. Some are made very fancy and have a small "hanging garden" along their centre surrounded with pools filled with beautiful fish. There must be fresh water flowing, either continuous or on demand. Also there must be seating. There is also a small banner-row of 3 banners ... in line with the "water-hut" and on the side away from the toilido.

There is often a tree lined avenue leading up to the front entrance of the toilido. In hot countries the trees are usually some sort of shade tree. In colder countries, trees with a well defined, uniform shape are favoured ... poplars ?? The two rows of trees diverge from each other as the road passes the row of three banners. They open up to encompass the "poster-huts" but don't extend beyond them.

The word toilido literally means "building of the books". It actually only refers to the hexagonal building (not the centre tower). The whole complex is actually called "centre station".

Usually 2 or 3 other types of tree are planted around the "centre station" (maybe 5 or 6 trees in all). This makes every toilido unique.

The whole complex provides the following services ...

1) A clocktower

2) Public toilets

3) A post office

4) A library

5) Archives for public records

6) A place for the parish council to meet

7) Offices for the parish council members

The black part of the toilido is the main entrance.

You will notice to "huts" with half their roof red and half black. These are the "poster huts". These are sheltered billboards for posting important information. The red side is for official notices (that is for what the parish officers or the central government think should be posted). On the black side the general public can post whatever it wants. New notices are posted on the small "poster hut". After 9 days they are transferred to the larger "poster huts". In béu the adjective "red" can be used to refer to something pertaining to the government, and the adjective "black" to refer to something non-government.

The orange part of the toilido is a stage, or actually the roof over the stage. And the area in front of this stage is a fairly large green where people gather to see the various shows that are put on. There are various conserts put on by the parish members at regular times every year. Also occasionally you get wondering groups of "players" who put on a show.

Above is how the toilido looks from street level (the "hut" to the left is the "water hut").

The entrance has about 1.3 m of steps to climb. There are three arches at every entrance. The central one being slightly higher than the other two.

(I have probably drawn the building too high in the street level view). Usually tall stain glass windows on 4 sides of the toilido. There is always at least 2 storeys within the main part of the building, sometimes more. Also usually there is a separate storey in the roof (the triangular shapes seen on the plan view, are actually windows in the roof to provide light to this storey. These windows look onto the central courtyard.)

The centre of the hexagon has a pleasing garden. In the very centre is the base of the "clock tower".

The 2 kidney shaped building are public toilets. The one on the right for the use of men, the one on the left for the use of women.

Tables and chair for setting out for the various concerts are also kept in these buildings. These toilets are kept meticulously clean. In fact every parishioner must do a certain amount of duty at the toilets every year ... keeping them clean. No fit adult is exempt from this duty.

There is a single banner just outside each of these buildings ... on the opposite side from the stage.

There are similar roof-colouring rules for other government buildings. Namely the schools have are gray-roofed and the hospitals are dark blue-roofed.

The town clock

Every town has a clocktower and the clocktower has 4 faces, which are aligned with the cardinal directions. The street pattern is also so aligned : that is the four biggest streets radiate out from the clock in the cardinal directions.

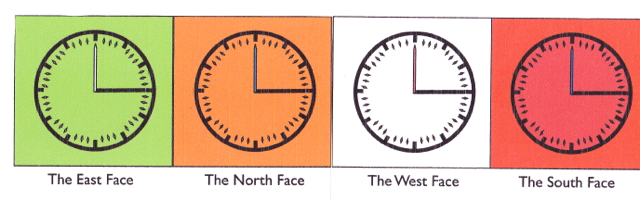

Each face displaying a clock similar to the one below.

The above figure shows the time at exactly 6 in the morning. You notice that the main (hour hand) hand is pointing to the right : it starts from the horizontal. This hand sweeps out one revolution in 24 hours and it moves anti-clockwise

Notice that secondary (minute hand) starts from the vertical and sweeps out a revolution in 2 of our hours. It moves clockwise. And actually when it passes the main hand, there is a clever mechanism to stop it being hidden. It stops 3.75 minutes at one side of the main hand, and then moves directly (2 steps) to the other side of the main hand and stops there for 3.75 minutes. After that it does a step and waits 2.5 minutes, etc. etc. ... until it encounters the main hand again.

The red and the black arms do not move continuously but move in steps. The primary arm moves 3.75 degrees every 15 minutes, and the secondary arm moves 7.5 degrees every 2.5 minutes.

The clocktower is surmounted by a green conic roof (actually not really conic ... the roof slope decreases as you get nearer the bottom). Lighting from under the roof could be provided for each face. Either that or the faces could be illuminated from within at night. The faces are not exactly vertical but the top slightly overhangs the bottom.

There is never any numbering on the face.

The clock also emits sounds. Every 2 of our hours the clock makes a deep "boing" which reverberates for some time. Also from 6 in the morning to 6 at night, the clock emits a "boing" every 30 of our minutes. The first "boing" has no accompaniment. However the second "boing" is followed (well actually when the "boing" is only .67 % dissipated) by a "sharper" sound that dies down a lot quicker : "teen". The third "boing" has 2 "teen"s 0.72 seconds apart. The fourth has 3 "teen"s. The fifth one is back to the single "boing" and so it continues thru the day.

The secondary hand and the 36 diamonds should be ...

East face => white or even better, silver

North face => light blue

West face => green

South face => dark blue

(The drawing is a bit out in this respect).

The time of day

dé = day

The béu day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called cuaju

The time of day is counted from cuaju. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called ajai (normally just called ajai, but cúa ajai or ajai yanfa might also be heard sometimes).

| 6 o'clock in the morning | cuaju |

| 8 o'clock in the morning | ajai |

| 10 o'clock in the morning | uvai |

| midday | ibai |

| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | agai |

| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | idai |

| 6 o'clock in the evening | ulai |

| 8 o'clock in the evening | icai |

| 10 o'clock at night | ezai |

| midnight | okai |

| 2 o'clock in the morning | apai |

| 4 o'clock in the morning | atai |

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon.

16:00 would be idai : 16:10 would be idaijau : 16:20 would be idaivau .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be idaitau

Now all these names have in common the element idai, hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called idaia (the plural of idai). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties".

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called cuajua. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time ajai was called ajaia(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time cuaju should be called cuajua. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial cuaju. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be cuaju ajau, "twenty past six" would be cuaju avau and so on.

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened idaia.pi

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them apaiʔe.

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued nàn uvau, for 2 hours : nàn ajai (nàn means "a long time")

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In béu they only have the yanfa. The yanfa is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as yanfa also.

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences