Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions: Difference between revisions

| Line 1,061: | Line 1,061: | ||

.. | .. | ||

In '''béu''' there is only one relativizer ... '''nài''' | In '''béu''' there is only one relativizer ... '''nài'''. For example ... | ||

'''glà nài bàus timpori_sòr hauʔe''' = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful. | |||

.. | |||

'''nài''' takes case affixes the same way that a normal noun would. For example ... | |||

pi ... the basket '''naipi''' the cat shat was cleaned by John. | |||

la ... the chair '''naila''' you are sitting was built by my grandfather. | |||

mau | |||

goi | |||

ce | |||

dua | |||

bene | |||

komo | |||

the town ''' | tu ... '''báu naitu ò''' is going to market is her husband = the man with which she is going to town is her husband ... '''kli.o naitu''' he severed the branch is rusty | ||

ji ... The old woman '''naiji''' I deliver the newspaper, has died. | |||

-s ... '''báu nàis timpori glá_sòr ʔaiho''' = The man that hit the woman is ugly. | |||

''' | wo ... The boy '''naiwo''' they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand. | ||

''' | -n ... the woman '''nàin''' I told the secret, took it to her grave. | ||

''' | fi ... the town '''naifi''' she has come is the biggest south of the mountain. | ||

''' | ?e ... '''nambo naiʔe''' she lives is the biggest in town = the house in which she lives is the biggest in town | ||

-lya ... the boat '''nailya''' she has just entered is unsound | |||

-lfe ... the lilly pad '''nailfe''' the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond. | |||

.. | .. | ||

The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its '''pilana''' on the suffixed to the relativizer. | |||

I shot '''waulo è waulo yana fyakasri pà pulison''' = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police ??? | I shot '''waulo è waulo yana fyakasri pà pulison''' = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police ??? | ||

Revision as of 19:28, 21 May 2016

..... Combining clauses

..

... With respect to time

..

huʒia = to smoke

koʔua = to cough

solbe = to drink

caume = medicine

..

... XXX

..

Grammar provides ways to make the stream of words coming out a speaker's mouth nice and smooth ... no lumpy bits. Well the smoothness comes from the rules (you can think of the rules as traffic rules, and affixes and particles as the traffic signs), and getting rid of the lumps entails dropping the elements that are already known, that are already accessible in the mind of the hearer. This section is about getting rid of these elements : both arguments and person-tense markers.

..

Now we have already come across the particle lé which links nouns together. béu doesn't use the same particle for linking clauses together though. It uses the particle è. English allows the dropping of an S or A argument in a sentence when this argument has already been established as the topic. béu is exactly the same : it allows the dropping of an S or A argument. However when you have a clause with the S argument dropped, this clause is not introduced by è, it is introduced by the particle sé. For example ...

A) bawa turi = The men came

B) bawas bwuri gala = The men saw some women

C) bawa turi sé bwuri gala = The men came and saw some women.

D) bawas bwuri gala è turi = The men saw some women and then came.

You can see that C) flows a lot better than A) juxtaposed with B). And D) flows a lot better than B) juxtaposed with A).

This seems a good place to list all the particles that can join clauses.

sé/è : these have nothing to say about the relative timing of clause A (before the particle) and clause B (after the particle).

sé dù/è dù : these mean that action B follows on immediately from action A.

sé kyude/è kyude : these mean that action B follows action A but not necessarily immediate. Sometimes sé è are dropped.

kyugo : this means that action A and B happen at the same time. Usually we have different actors in the two clauses, but not always.

Another particle used for combining clauses is tè. This is exactly equivalent to the English "but". tè is occasionally also used before nouns. However before nouns it is more usual to use ???

There are also some phrases with more "sound.weight" that have the exact same meaning as tè.

..

..... The three types of Verb

..

Some concepts are naturally intransitive. Like "to shave". Well at least in béu it is very unusual to shave another.

Some concepts are naturally transitive. Like "to hit". It is worth remarking on when somebody hits themselves.

And there are also some concepts that appear in both manifestations. For example ... "turn", "spread", "rise/raise"

These three types of concept are represented in beu by three different types of verb.

V1) té = to come ... this is a intransitive verb

(Always accompanied by a naked noun)

V2) timpa = to hit ... this is a transitive verb

(Always accompanied by an s-marked noun and a* naked noun)

*Although sometimes the naked noun can be dropped for lack of interest. For example ...

jenes solbori = Jane drank (something)

V3) kwèu = to turn

Now this sometimes behaves like V1 and sometimes like V2.

..

.. V1 Derivations

..

There are 5 deriuvation processes shown below ...

First from doika => doikaya This involves infixing ay before the final vowel.

Secondly from doika => doikana and doikaya => doikayana.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding ana.

Thirdly from doika => doikala and doikaya => doikayala.

This involves deleting the second part of the final vowel if it is a diphthong, and then adding la.

Fourthly from doikaya => doikaiwai.

This involves deleting the final vowel and y and adding iwai.

Fifthly from doikaya => doikaiwau.

This involves deleting the final vowel and y and adding iwau.

..

| doikaiwai | doikaiwau | |||

| "that which has been made to walk" (A/N) | "that which must be made to walk" (A/N) | |||

| doikayana | <============ | doikaya | ============> | doikayala |

| "the one that makes walk" (N) | "to make to walk" (V1) | "causing to walk" (A) | ||

| ^ | ||||

| | | ||||

| | | ||||

| doikana | <============ | doika | ============> | doikala |

| "walker" (N) | "to walk" (V2) | "walking" (A) |

Note that we have 8 word forms in total.

..

.. V2 Derivations

..

There are 5 deriuvation processes shown below ...

First from kludau => kludawau This involves infixing aw before the final vowel.

Secondly from kludau => kludana and kludawau => kludawana.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding ana.

Thirdly from kludau => kludala and kludawau => kludawala.

This involves deleting the second part of the final vowel if it is a diphthong, and then adding la.

Fourthly from kludau => kludwai.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding wai.

Fifthly from kludau => kludwau.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding wau.

..

| kludawana | <============ | kludawau | ============> | kludawala |

| "computer memory" (N) | "to be written" (V2) | "being written" (A) | ||

| ^ | ||||

| | | ||||

| | | ||||

| kludana | <============ | kludau | ============> | kludala |

| "writer" (N) | "to write" (V1) | "writing" (A) | ||

| kludwai | kludwau | |||

| "written" (A/N) | "which must be written" (A/N) |

..

kludwai is the passive past participle, and kludwau is the passive future participle.

..

Note that we have 8 word forms in total.

..

.. V3 Derivations

..

| haikana | <============ | haika | ============> | haikala |

| "breaker" (N) | "to break" (V3a) | "breaking" (A) | ||

| haikwai | haikwau | |||

| "broken" (A/N) | "that which must be broken" (A/N) |

..

Note ... haikwai could very well have broken by itself. There is no connotation that an outside agent was responsible. The same with haikwau.

..

| heukana | <============ | heuka | ============> | heukala |

| "breaker" (N) | "to break" (V3b) | "breaking" (A) |

..

There are 4 derivational processes involved with V3a and 2 derivational processes involved with V3b. They have been already been explained in the sections on V1 and V2.

Note that we have 8 word forms in total.

kó = to see

kowa = to be seen

The subject of the active clause, can be included in the passive clause as an afterthought if required. hí is a normal noun meaning "source". However it also acts as a particle (prefix) which introduces the agent in a passive clause.

poʔau = to cook

..

When the final consonant is w y h or ʔ the passive is formed by suffixing -wa

In monosyllabic words, it is formed by suffixing -wa.

Note ... when wa is added to a word ending in au or eu, the final u is deleted.

Also note ... these operations can make consonant clusters which are not allowed in the base words. For example, in a root word -mpw- would not be allowed ( Chapter 1, Consonant clusters, Word medial)

..

... Valency ... 1 => 2

..

Now all verbs that can take an ergative argument can undergo the 2=>1 transformation.

There also exists in béu a 1=>2 transformation. However this transformation can only be applied to a handful of verbs. Namely ...

| ʔoime | to be happy, happyness | ʔoimora | he is happy | ʔoimye | to make happy | ʔoimyana | pleasant |

| heuno | to be sad/sadness | heunora | she's sad | heunyo | to make sad | heunyana | depressing |

| taudu | to be annoyed | taudora | he is annoyed | tauju | to annoy | taujana | annoying |

| swú | to be scared, fear | swora | she is afraid | swuya | to scare | swuyana | frightening, scary |

| canti | to be angry, anger | cantora | he is angry | canci | to make angry | cancana | really annoying |

| yodi | to be horny, lust | yodora | she is horny | yoji | to make horny | yojana | sexy, hot |

| gái | to ache, pain | gayora | he hurts | gaya | to hurt (something) | gayana | painful * |

| gwibe | to be ashamed/shame/shyness | gwibora | she is ashamed/shy | gwibye | to embarrass | gwibyana | embarrassing |

| doimoi | to be anxious, anxiety | doimora | he is anxious | doimyoi | to cause anxiety, to make anxious | doimyana | worrying |

| ʔica | to be jealous, jealousy | ʔicora | she is jealous | ʔicaya | to make jealous | ʔicayana | causing jealousy |

ʔoimor would mean "he is happy by nature". All the above words take this sense when the "a" of the present tense is dropped.

The above words are all about internal feelings.

The third column gives a transitive infinitive (derived from the column two entry by infixing a -y- before the final vowel).

The fourth column gives an adjective of the transitive verb (derived from column three entry by affixing a -ana ... the active participle).

When the final consonant is ʔ j c w or h the causative is formed by suffixing -ya.

Also when the verb is a monosyllable, the causative is formed by suffixing -ya.

Note ... when ya is added to a word ending in ai or oi, the final i is deleted.

Note ... when y is infixed behind t and d : ty => c and dy => j

..

Normally in béu, to make a nominally intransitive verb transitive, it doesn't need the infixing of -y. All it needs is the appearance of an ergative argument. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikor = he walk

ós doikor the pulp mill = he runs the pulp mill

doikyana = management ???

..

*You would describe a gallstone as gayana. However you would describe your leg as gaila (well provided you didn't have a chronic condition with your leg)

..

Concatenation of the valency changing derivations ... 1 => 2 => 1 and 2 => 1 => 2

..

| ʔoime | = to be happy | ʔoimye | = to make happy | ʔoimyewa | = "to be made to be happy" or, more simply "to be made happy |

..

| fàu | = to know | fa?? | = to tell | fa ?? | = |

..

| timpa | = to hit | timpawa | = to be hit | timpawaya | = to cause to be hit |

..

Semantically timpa is direct action (from agent to patient). Whereas timpawaya is indirect, possibly involving some third party between the agent and the patient and/or allowing some time to pass, between resolving on the action and the action being done unto the patient.

..

..... 9 important verbs

..

| pòi | to enter, to join | poinau | to put in |

| féu | to exit, to leave | feunau | to take out |

| bwí | to see | bwinau | to show |

| glù | to know | glunau | to tell |

| pyà | to fly | pyanau | to throw |

| jó | to go | jonau | to send |

| tè | to come | tenau | to summon |

| bái | to rise | bainau | to raise |

| kàu | to fall | kaunau | to lower |

..

pyà _ jó _ tè _ bái and kàu are intransitive.

..

..... Word building

..

Many words in béu are constructed from amalgamating two basic words. The constructed word is non-basic semantically ... maybe one of the concepts needed for a particular field of study.

..

In béu when 2 nouns are come together the second noun qualifies the first. For example ...

toili nandau (literally "book" "word") ... the thing being talk about is "book" and "word" is an attribute of "book".

Now the person who first thought of the idea of compiling a list of words along with their meaning would have called this idea toili nandau.

However over the years as the concept toili nandau became more and more common, toili nandau would have morphed into nandəli.

Often when this process happens the resulting construction has a narrower meaning than the original two word phrase.

There are 4 steps in this word building process ...

1) Swap positions : toili nandau => nandau toili

2) Delete syllable : nandau toili => nandau li

3) Vowel becomes schwa : nandau li => nandə li

4) Merge the components : nandə li => nandəli

The above example is for 2 non-monosyllabic words. In the vast majority of constructed words the contributing words are polysyllables.

The process is slightly different when a contributing word is a monosyllabic. First we look at the case when the main word is a monosyllable ...

wé deuta (literally "manner soldier")

1) Swap positions : wé deuta => *deuta wé ........ there is no step 2

3) Vowel becomes schwa : *deuta wé => *deutɘ wé

4) Merge the components : *deutə wé => deutəwe

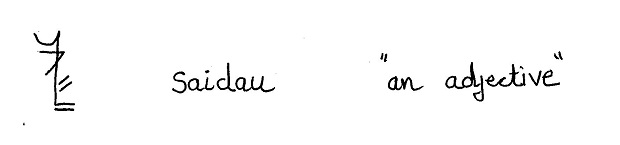

And the case when the attribute is a monosyllable ...

nandau sài (literally "word colour")

1) Swap positions : *sài nandau

2) Delete syllable : *sài dau .......................................... there is no step 3

4) Merge the components : *sài dau => saidau

And the case when the attribute ends in a consonant ...

megau peugan ... "body of knowledge" "society"

1) Swap positions : *peugan megau

2) Delete syllable : *peugan gau

3) Delete the coda and neutralize the vowel :*peugan gau => *peugə gau

4) Merge the components :*peugən gau => peugəŋgau

And the case when the main word has a double consonant before the end vowel ...

kanfai gozo ... merchant of fruit

1) Swap positions : *gozo kanfai

2) Delete syllable : *gozo fai ............................. Note kan is deletes, not just ka

3) Vowel before the final consonant becomes schwa :*gozo fai => *gozə fai

4) Merge the components :*gozə fai => gozəvai

There are no cases where both contributing words are monosyllables.

Note ...

1) the schwa is represented by a sturdy dot.

2) the consonant before the schwa takes its final form

3) the consonant after the schwa takes its medial form

When spelling words out, this dot is pronounced as jía ... meaning "link".

Notice that when you hear nandəli, deutəwe or peugəgau you know that they are a non-basic words (because of the schwa).

Also when you see nandəli or deutəwe, peugəgau written you know that they are non-basic words (because of the dot).

However when you come across hipe it is not immediately obvious that it's a non-basic word.

This method of word building is only used for nouns.

..

..... Bicycles, Insects and Spiders

..

wèu = vehicle, wagon

weuvia = a bicycle

weubia = a tricycle

Perhaps can be thought of derived from an expression something like "wagon two-wheels-having" or "wagon double-wheel-having" with a lot of erosion.

Notice that the "item" that is numbered (i.e. wheel) is completely dropped ... probably not something that would evolve naturally.

There are not many words in this category.

jodoʒia* = spider

jodolia = insect

jodogia = quadraped

jodovia = biped

nodebia = a three-way intersection ... usually referring to road intersections.

nodegia = a four-way intersection

nodedia = a five-way intersection

nodelia = a six-way intersection ... and you can continue up of course.

*jodo = animal ... from jode = to move

..

..... Ambitransitive verbs

..

In English there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes involve two participants. For example "knit" or "turn". In English you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up after the verb (that is ... an O argument has turned up) ... S and A appear the same in English.

Similarly in béu there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes take two participants. For example mekeu "knit" or kwèu "turn". In béu you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up with the ergative marker -s attached (that is ... an A argument has turned up) ... S and O appear the same in béu.

Note on nomenclature

Dixon calls "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitive verb of type S=A or an [S=A ambitransitive verb].

I call "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one unaffected argument" or an [unaffected ambitransitive verb].

For "knit" the preverb argument* is either S or A .... For mekeu the unaffected argument is either S or A.

Dixon calls "turn"/kwèu is an ambitransitive verb of the type S=O or an [S=O ambitransitive verb].

I call "turn"/kwèu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one affected argument" or an [affected ambitransitive verb].

For "turn" the affected argument is either S or O .... For kwèu the naked argument** (i.e. no -s) is either S or O.

*It is also the unaffected argument.

**It is also the affected argument.

..

..... More on definiteness

..

In the section on word order we said that when the person being spoken to can identify X as one particular X ... then X will come before the verb, where X is any of the A O or S arguments.

However ... the above leaves undefined, whether the person speaking can identify X. This can be made explicit in béu by adding either the particle é or the participle fawai. For example ...

doikora bàu = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known-ness to the person speaking is not defined.

doikora é bàu = Some man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : unknown to the person speaking.

doikora bàu fawai = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known to the person speaking.

This distinction is also made in certain natural languages. For example with nouns in Samoan ...

o sa fafine = a woman

o le fafine = a woman ……. unknown to you but known to me

Or between these two indefinite pronouns in Latin ...

aliquis = somebody

quidam = somebody ……. unknown to you but known to me

[ Note ... the argument qualified by é or fawai invariably come after the verb. Also, while it is possible to imagine some scenario where an argument is known to the person being spoken to but unknown to the person speaking, in reality this very very rarely happens and I know of no natural language that makes this distinction. ]

..

One interesting point .....

Take the sentence ... "She wants to marry a Norwegian"

How do we show the definiteness of the Norwegian in relation to the subject. That is ... does she have a certain Norwegian in mind or does she want to marry any Norwegian.

In English ... when you hear this sentence ... you will nearly always know from the context, which of the two meanings is meant.

"any" or "that she knows" could be added to make the distinction explicit within the sentence itself.

..

..... Questions

..

... The 9 Question Words

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 7 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

These are the most profound words in the English language.

However these question words have over the mellenia been sequestered to support other functions. For example "who" can be used to ....

1) Solicit a response in the form of a persons identity

2) As a relativizer particle ... for example ... "The man who kicked the dog"

3) As a complement clause particle ... for example ... "She asked who had kicked the dog"

4) In the compound "whoever" which is an indefinite pronoun.

Only in the first example is "who" asking a question.

..

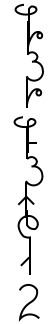

béu has 9 question words ...

..

| dá | where |

| kyú | when |

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| láu | "how much" or "how many" |

| nái | which |

| ʔala | which |

| ʔai? | "solicits a yes/no response" |

..

If you hear any of these words you know you are being solicited for some information. That is these words have no other function apart from asking questions.

..

nós and mís are the ergative equivalents to nén and mín (the unmarked words)

English is among the 1/3 of world languages which fronts a question word. I guess béu would be considered a content-question-word-fronter as well.

dá kyú nén nós mín and mís are always sentence initial. (but pilana are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.)

kái láu and nái are usually found in a NP. These NP's are always made sentence initial. ( kái and nái appearing after the head, láu before. )

Here are some examples of these words in action ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 ... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 ... í mín bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 ... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... í glá nái bàus nori alha = the man gave the flowers to which woman ?

Question 5 ... á bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 6 ... alha kái bàus glán nori = what type of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 7 ... láu alha bàus glán nori = how many flowers did the man give the woman

Question 8 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔala cokolate = Did the man gave the woman flowers or chocolate ?

Question 9 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man gave the woman flowers ?

..

"why" is expressed as nenji which means "what for" (by the normal pilana rules, it should be jì nén. However jì nén is never seen ... always nenji)

"how" is expressed as wé nái which means "which way" or "which manner"

..

... Polar Questions and the focus particle

..

A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

To turn a normal statement into a polar question the particle ʔai? is stuck on at the very end.

It has its own symbol (and I transcribe it as ʔai?) because it possesses its own tone contour.

I have mentioned this particle in chapter 1 (if you look back you can see its exact tone contour). Here is its symbol again ...

And here is an example of it in action ...

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

..

ʔai? is neutral as to the response expected ... well at least in positive questions.

To answer a positive question you answer ʔaiwa "yes" or aiya "no" (of course if "yes" or "no" are not adequate, you can digress ... the same as any language).

Here is an example of a positive question ...

glá r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman beautiful ?

If she is beautiful you answer ʔaiwa, if not you answer aiya*.

..

To answer a negative question it is not so simple. ʔaiwa and aiya are deemed insufficient to answer a negative question on their own. For example ...

glá bù r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman not beautiful ?

If she is not beautiful, you should answer bù hauʔe**, if she is you can answer either cù hauʔe or glá r hauʔe

I guess a negative question expects a negative answer, so a positive answer must be quite accoustically prominent (that is a short answer ("yes" or "no") is not enough)

..

You will have noticed cù in the above example. This is the focus particle. It has a number of uses. When you want to emphasis one word in a clause, you would stick cù in front of it***.

Another use for cù is when hailing somebody .... cù jono = Hey Johnny

You can also stick it in front of someone's name when you are talking to them. However it is not a "vocative case" exactly. Well for one thing it is never mandatory. When used the speaker is gently chiding the listener : he is saying, something like ... the view you have is unique/unreasonable or the act you have done is unique/unreasonable. When I say unique I mean "only the listener" hold these views : the listener's views/actions are a bit strange.

cù can also be used to highlight one element is a statement or polar question. For example ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement ... bàus cù glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.****

Unfocused question ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man give flowers to the woman ?

Focused statement ... bàus cù glán nori alha ʔai? = It is to the woman that the man gave flowers ?

..

Any argument can be focused in this way. In fact the verb can also be focused using this method.

..

*These words have a unique tone contour as well ... at least when spoken in isolation. I suppose I should have given these two words a symbol each ... if I wanted to be consistent.

**Mmm ... maybe you could answer ʔaiwa here ... but a bit unusual ... not entirely felicitous.

***In English, when you want to emphasis a word, you make it more accoustically prominent : you don't rush over it but give it a very careful articulation. This is iconic and I guess all languages do the same. It is a pity that there is no easy way to represent this in the English orthography apart from increasing the font size or adding exclamation marks.

****English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to an element in a clause.

(make cù => hù : make imperative for short verbs ?)

..

... The Generic noun equivalents

..

..

| dà | place |

| kyù | occasion |

| nèn nòs | thing |

| mìn mìs | person |

| kài | kind, type, sort |

..

| làu | amount |

..

... The Relativizer

..

In English, one of the functions of "who" is as a relativizer ... a particle that introduced a relative clause. For example ....

"The man who ate the chicken got sick"

Also in English, one of the functions of "that" is as a relativizer. For example ....

"The chicken that was eaten must have been off"

..

In béu there is only one relativizer ... nài. For example ...

glà nài bàus timpori_sòr hauʔe = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful.

..

nài takes case affixes the same way that a normal noun would. For example ...

pi ... the basket naipi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

la ... the chair naila you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

mau

goi

ce

dua

bene

komo

tu ... báu naitu ò is going to market is her husband = the man with which she is going to town is her husband ... kli.o naitu he severed the branch is rusty

ji ... The old woman naiji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

-s ... báu nàis timpori glá_sòr ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

wo ... The boy naiwo they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

-n ... the woman nàin I told the secret, took it to her grave.

fi ... the town naifi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

?e ... nambo naiʔe she lives is the biggest in town = the house in which she lives is the biggest in town

-lya ... the boat nailya she has just entered is unsound

-lfe ... the lilly pad nailfe the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

..

The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its pilana on the suffixed to the relativizer.

I shot waulo è waulo yana fyakasri pà pulison = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police ???

I shot waulo è yana fyakasri pà polison = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police ???

This is basically the same as "what" in English, in such sentences as ...

"WHAT you see is WHAT you get"*

Notice that "you see" and "you get" are not complete clauses, there is a "gap" in them.

The phase "WHAT you see", (to return to the mathematical analogy again) may be thought of as a "variable". in this case, the motivation for using a "variable", is to make the expression "general" rather than "specific". (Being general it is of course more worthy of our consideration). Other motivations for using a "variable" is that the actual argument is not known. Yet another is that even though the particular argument is known, it is really awkward to specify satisfactorily.

EXAMPLE

Another way to think about the hù construction, is to think of it as a "nominalizer", a particle that turns a whole clause into a noun. To use the example from just above ....

"see" is an intransitive verb with two arguments. To replace one of these arguments by ʔà is like defining the missing argument in terms of the rest of the clause i.e. it changes a clause into a construction that refers to one argument of that clause.

. Gap clause particles in other languages

There is no generally agreed upon term for the type of construction which I am calling "gap clause" here. Dixon calls it a "fused relative", Greenberg calls it a "headless relative clause". I don't like either term. A fused relative implies that a generic noun (i.e. "thing" or "person") somehow got fused with a relativizer. This certainly never happened although this type of clause can be rewritten as a generic noun followed by a relativizer. As for "headless" relative clause ... well I think the type of clause that we are dealing with is in fact more fundamental then a relative clause, so I would not like to define it in terms of a relative clause.

My thoughts on this type of clause are ...

Well "what" was firstly a question word. So you have expressions like "Who fed the cat"

Then of course it is natural to have an answer like "I don't know who fed the cat"

Now the above sentence is similar to "I don't know French" or "I don't know Johnny".

Now you see the expression "who fed the cat" fills the slot usually occupied by a noun in an "I don't know" sentences.

So "who fed the cat" started to be thought of as a sort of noun.

Now from the "know (neg)" beachhead*, the usage would have spread to "know" and also the such words that have "knowing" as an essential part of their meaning. Words such as "remember", "report" etc. etc.

*I call "know (neg)" a "beachhead"**. A beachhead is a usage(and/or the act or situation behind that usage) that facilitates the meaning of a word to spread. Or the meaning of an expression to spread. A beachhead can be defined simply as an expression, but sometimes some background as to the speakers environment has to be given. For example suppose that one dialect of a language was using a word to mean "under", but this same word meant "between/among" in all other dialects. Now suppose you did some investigating and found that all other dialects of this language was spoken on the steppes and their speakers made a living by animal husbandry. However the group which diverged from the others had given up the nomadic life and settled down in a lush river valley. In this valley their main occupation was tending their fruit orchards.

It could be deduced that the change in meaning came about by people saying ... "Johnny is among the trees". Now as the trees were thick on the ground and had overspreading branches, this was re-analysed to mean "Johnny is under the trees". Hence I would say ...

The beachhead of word "x" = "between" to word "x" = "under" was the expression "among the trees" (and in this case a bit of background as to the "culture" of the speakers would be appropriate). ... OK ? ... understood ?

For an expressing to become a beachhead, it must, of course, be used regularly.

ASIDE ... I have thought about counting rosary beads as a possible beachhead that changed the meaning of "have", in Western Europe, from purely "possession" to a perfect marker. This is just (fairly ?) wild conjecture of course. (The beachhead expression being "I have x beads counted" with "counted" originally being a passive participle)

I am digressing here ... well to get back to "who fed the cat". We had it being considered a sort of noun. Presumably it was at one time put directly after a noun in apposition (presumably with a period of silence between the two) and qualified the noun. Then presumably they got bound closer together, the gap was lost, and this is the history of one form of relative clause in English.

**Actually I would have liked to use the term pivot here. However this term has already been taken.

From the dictionary

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 1. A position on an enemy shoreline captured by troops in advance of an invading force

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 2. A first achievement that opens the way for further developments.

There are 4 relativizers ... ʔá, ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja. (relativizer = ʔasemo-marker)

ʔasemo = relative clause.

It works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. The béu relativisers is ʔá. Though ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja also have roles as relativisers.

The main relativiser is ʔá and all the pilana can occur with it (well all the pilana except ʔe. ʔaí is used instead of * ʔaʔe).

Note ... we have no direct translation of "whose".

*Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. n marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause.

As you see in above, ʔa in the form * ʔaʔe is not allowed. Instead you must use ʔaí.

The use of ʔái and ʔàu as relativizers are basically the same as the use of "where" and "when" in English. These two can combine with two of the pilana.

?aifi = from where, whence

?aiye = to where, hence

?aufi = from when, since

?auye = to when, until

The use of ʔaja basically is a relativizer for an entire clause instead of just the noun which it follows.

For example ???????

WITH SPACE AND TIME

PLURAL FORM

..

.. Specifiers X determiners

..

Below is a table showing all the specifiers plus a countable noun plus the proximal determiner "this".

..

| 1 | ù báu dí | all of these men OR all these men |

| 2 | hài báu dí | many of these men |

| 3 | iyo báu dí | few of these men OR a few of these men |

| 4 | auva báu dí | two of these men => ataitauta báu dí ... 1727 of these men |

| 5 | jù báu dí | none of these men |

| 6 | í báu dí | any of these men OR any one of these men |

| 7 | é báu dí | one of these men |

| - 8 - | éu báu dí | some of these men |

| 9 | ?? báu dí | every one of these men |

| 10 | nò báu dí | several of these men OR several of these men here |

| 11 | é nò báu dí | one or more of these men ??? |

| 12 | í auva báu dí ... | any 2 of these men => í ataitauta báu dí ... any 1727 of these men |

..

The above table is worth discussing ... for what it tells us about English as much as anything else.

..

One line 1 ... I do not know why "all these men" is acceptable ... on every other line "of" is needed (to think about)

Similarly on line 3 ... I do not know why "a few" is a valid alternative.

Notice that *aja báu dí does not exist. It is illegal. "one of these men" is expressed on line 7. aja only used in counting ???

I should think more on the semantic difference between line 10 and line 8. ???

line 1 and line 9 are interesting. Every language has a word corresponding to "every" (or "each", same same) and a word corresponding to "all". Especially when the NP is S or A, "all" emphasises the unity of the action, while "every" emphasises the separateness of the actions. Now of course (maybe in most cases) this dichotomy is not needed. It seems to me, that in that case, English uses "every" as the default case (the Scandinavian languages use "all" as the default ??? ). In béu the default is "all" ù.

On line 9, it seems that "one" adds emphasis to the "every". Probably, not so long ago, "every" was valid by itself. The meaning of this word (in English anyway) seems particularly prone to picking up other elements (for the sake of emphasis) with a corresponding lost of power for the basic word when it occurs alone. (From Etymonline EVERY = early 13c., contraction of Old English æfre ælc "each of a group," literally "ever each" (Chaucer's everich), from each with ever added for emphasis. The word still is felt to want emphasis; as in Modern English every last ..., every single ..., etc.)

..

This table is also valid for the distal determiner "that". For the third determiner ("which") the table is much truncated ...

..

| 1 | nò báu nái | which men |

| 2 | ... auva báu nái | which two men => ataitauta báu nái which 1727 of these men |

..

Below I have reproduced the above two tables for when the noun is dropped (but understood as background information). It is quite trivial to generate the below tables. Apart from lines 8 and 10, just delete "men" from the English phrase and báu from the béu phrase. (I must think about why 8 and 10 are different ???)

..

| 1 | ù dí | all of these OR all these |

| 2 | uwe dí | many of these |

| 3 | iyo dí | few of these OR a few of these |

| 4 | auva dí | 2 of these => ataitauta dí ... 1727 of these |

| 5 | kyà dí | none of these |

| 6 | í dí | any of these OR any one of these |

| 7 | é dí | one of these |

| - 8 - | è dí | some of these OR several of these |

| 9 | yú dí | every one of these |

| 10 | nò dí | these NOT several of these |

| 11 | é nò dí | one or more of these |

| 12 | í auva dí ... | any 2 of these => í ataitauta dí ... any 1727 of these |

..

| 1 | nò nái | which ones |

| 2 | ... auva nái | which two => ataitauta nái which 1727 |

..

In the last section we introduced the rule, that when a determiner is the head, then the determiner changes form (an a is prefixed to it)

Now we must introduce an exception to that rule ... when you have a specifier just to the left of a determiner (in this conjunction, the determiner MUST be the head) the determiner takes its original form.

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences