Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun: Difference between revisions

| Line 248: | Line 248: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| 11 | |align=center| 11 | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| ''' í ''' | ||

|align=center| -'''s''' | |align=center| -'''s''' | ||

|align=center| "ergative case" | |align=center| "ergative case" | ||

| Line 258: | Line 258: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| 13 | |align=center| 13 | ||

|align=center| '''ná''' | |align=center| '''ná''' or '''àn''' | ||

|align=center| -'''n''' | |align=center| -'''n''' | ||

|align=center| to | |align=center| to | ||

| Line 273: | Line 273: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| 16 | |align=center| 16 | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''alya''' | ||

|align=center| -''' | |align=center| -'''lya''' | ||

|align=center| onto | |align=center| onto | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 433: | Line 433: | ||

'''dùa nambo yinkai hauʔe''' = beyond the house of the pretty girl | '''dùa nambo yinkai hauʔe''' = beyond the house of the pretty girl | ||

.. | .. | ||

Revision as of 18:21, 28 February 2016

..... Pronouns

..

Here, for a transitive clause, "that which initiates the action" is called the A argument, and "that which is affected by the action" the O argument. Also, for an intransitive verb, the noun is called the S argument. It is convenient to make a distinction between all three cases. I follow the linguist RMW Dixon in using this terminology.

In most languages the S argument is marked the same way as the A argument. However in some languages the S argument is marked the same way as the O argument. These are called ergative languages. béu is one of these ergative languages. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative.

Below are the béu pronouns for the S and O arguments. This form can be considered the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | wìa | inclusive |

| us | yùa | exclusive | ||

| you | gì | you | jè | |

| him, her | ò | them | nù | |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

Below are the pronouns for the A arguments ( the ergative arguments ).

Pronouns differ from nouns in that their tones change between the ergative and the non-ergative form. This is in addition to the normal suffixing of -s when a noun becomes marked as ergative.

..

| I | pás | we | wías |

| we | yúas | ||

| you | gís | you | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

jè and jés are the second person plural forms.

There is one other pronoun ... the reflexive pronoun tí. This is always an O argument. Notice that it is the only O argument with a high tone.

There is a strong tendency for it to come after the A argument. For example ...

jonos tí timporja jindin = john has not yet hit myself

This particle can be amalgamated to the infinitive to give a reflexive infinitive. For example ...

timpa = to hit ... ti.timpa = "to self-hit"/ "to hit oneself"/"to hit yourself"

[ A dot is used to show that the word comprises two separate elements. I suppose most linguists would use "=" to show cliticization. The dot makes no difference to the pronunciation ]

I suppose I should also mention the reciprocal particle bèn at this point. It always follows the verb. For example ...

jonos jenes timpur bèn = John and Jane hit each other.

The plural pronouns above can also combine with specifiers (and number) to make pronoun phrases.

Below is a table with nù "them".

The other plural pronouns pattern in a similar way. That is ... yùa, wìa, jè and ʃì

..

| jù nù | none of them | ù nù | all of them | ||

| í nù | any of them | é nù | one of them | éu nù | some of them |

| hài nù | many of them | iyo nù | few of them | ||

| haige nù | more of them | iyoge nù | less of them | ||

| haimo nù | most of them | iyomo nù | a minority of them |

..

Notice that nò uhai haizo and haizmo are 4 specifiers that are never used with pronouns. I don't know why.

..

..... Word order

..

In English it is the order of the verb and the arguments that shows who is the doer and what is the "done to". Namely the A and S argument come before the verb and the O argument after.

[ English is a non-ergative language and hence the A and S argument get treated in the same way. ]

In béu, to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", the suffix -s is appended to the A argument. For example ...

glás bàu timpra = The woman has hit the man

glá bàus timpra = The man has hit the woman

bàu r doikala = The man is walking

[ béu is an ergative language and hence the O and S argument have the same form. ]

But even though béu doesn't use word order to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", it does use word order for another purpose. Namely to show if an argument is definite* or not. For example ...

bàu doikr = The man walks

doikr bàu = A man walks

So we see ... an argument coming before the verb is definite and one coming after the verb is indefinite.

[ *And when we say definite, we mean that the person being spoken to can identify X as one particular X instead of some X or any X. ]

In English only 2 orders are found. Namely ... SV and AVO ... (V = verb). However in béu you have what is called "free word order". This means that you can come across the following 8 orders ... SV, VS, AVO, AOV, VAO, OVA, OAV and VOA.

But actually in a piece of discourse, it is most likely that the S or A argument are old information and probably the topic (the thing that you have been going on about for some time). In béu an established topic is usually dropped and so the 8 sentence types shown above collapse into 3 sentence types. Namely ... V(s), O V(a) and V(a) O

[ V(s) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the S argument and V(a) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the A argument ]

..

..... The Case System

..

| preposition ... | suffix form | meaning | |

| 1 | pí | -pi | in |

| 2 | là | -la | on |

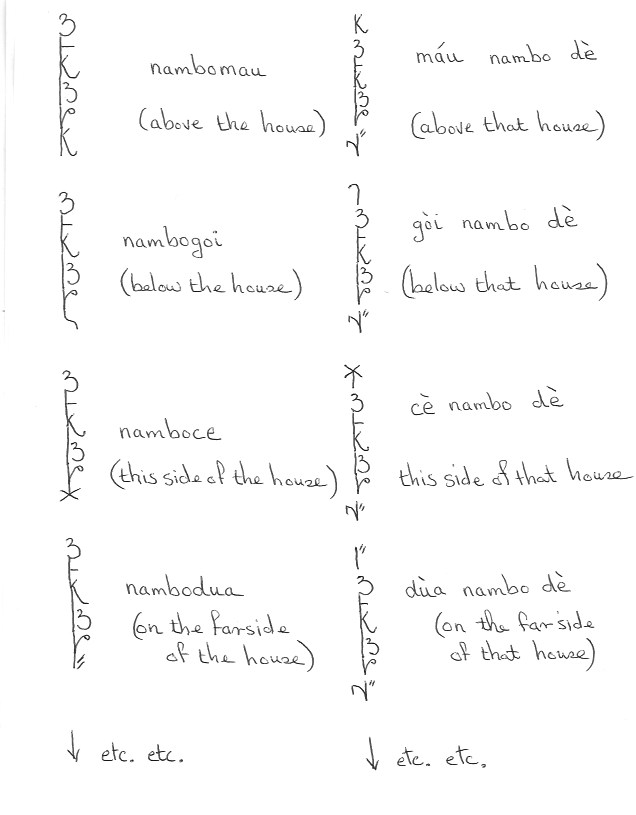

| 3 | máu | -mau | above |

| 4 | gòi | -goi | below |

| 5 | cé | -ce | near side |

| 6 | dùa | -dua | far side |

| 7 | bene | -bene | RHS of |

| 8 | komo | -komo | LHS of |

| 9 | tú | -tu | with |

| 10 | jì | -ji | for |

| 11 | í | -s | "ergative case" |

| 12 | wò | -wo | about |

| 13 | ná or àn | -n | to |

| 14 | fì | -fi | from |

| 15 | ʔí | -ʔi | at |

| 16 | alya | -lya | onto |

| 17 | alfe | -lfe | off |

..

We have just mentioned the ergative case. In total there are 17 cases of course (if you were to include the unmarked case as well you have 18 different forms). They are called the pilana.

These are suffixed to a noun and show how that word stands in relation to the rest of the sentence.

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila (v) = to place, to position

pilana (a, n) = positioning, the positioner

Specific Location

The first 8 define location.

1) -pi = in

2) -la = on

3) -mau = above, over, on top of

4) -goi = below, under, underneath, beneath

5) -ce = this side of

6) -dua = beyond, at the far side of

7) -bene = right, at the right hand side of

8) -komo = left, on the left hand side of

These are used to give a location with respect to some object. For example …

nambopi = in the house

nambomau = on the house, over the house

[ Note ... in a lot of situations, where "on" would be used in English, "above" is used in béu. For example ...

"John is on the mountain" = "jono r pobomau" not "jono r pobola" ]

Roll

The next 4 define the roll that the noun plays in the sentence.

9) -tu = with, using

10) -ji = for, for the benefit of

11) -s = “the ergative case”

12) -wo = about, with respect to

bàus glaji nambo bundra kontotu = the man has built the house for the woman with a hammer

gala bauwo catur = the women talk about the man

[ There are a number of words which end in 'a consonant. For these words the ergative case is indicated by adding -es. For example ...

yaivanes gador wìa = "possessions slow one down" : Note ... this is the only instance of a word final schwa ]

Motion

The next 2 specify motion.

13) --n = to

14) -fi = from

Now these are used to give a motion with respect to some object. For example …

nambon = to the house

nambofi = from the house

[ For words ending in a consonant, the dative suffix is -on. For example ...

nén = what, nenon = to what : mín = who, minon = to who ]

General Location

The next is a “general locative”.

15) -ʔi = at, on, in

glá (yó) pà r namboʔi = My wife is at home

flovan gì r pazbaʔi = Your food is on the table

boloŋgai r flovanʔi = the flies are at the food (some buzzing around and some crawling on the surface of the food)

boloŋga r flovanʔi = the fly is at the food (sometimes buzzing around and sometimes crawling on the surface)

boloŋga r flovanla = the fly is on the food (i.e. its legs are touching the food)

Hybrids of motion & position

The last two define motion AND position. They are sort of hybrids of the second pilana and the pilana of motion.

16) -lna = onto

17) -lfe = off

..

.. As parts of speech

..

pilana of location phrases (i.e. nouns with 1 -> 8 or 15) can be considered adjectives if they come after a noun and adverbs if they come after a verb. They must come after a noun or a verb. Sometimes they come after the copula*. In this case they are adjectives. Now often the copula is dropped ... but if this dropping results in any ambiguity it can be readily "undropped".

pilana of motional phrases (i.e. nouns with 13, 14, 16 or 17) can be considered adverbs. They can come in any position because it is understood that they are qualifying the verb.

pilana phrases defining sentence rolls (i.e. nouns with 9, 10, 11 or 12) can come anywhere. They are considered nouns.

* [ Notice that in English, you can either say ... "a bird is in the tree" or "in the tree is a bird"

In béu only jwado r ʔupaiʔi is valid ... also note that in this case jwado is not definite because it is left of the verb. That rule doesn't work with the copula. ]

..

. Stand alone forms

..

In all the above examples the noun that the pilana qualifies is a single word. However when the pilana qualifies a NP the pilana is not a suffix but appears as an independent word. This particle comes before the NP. For example …

nambodua = beyond the house

dùa nambo yinkai hauʔe = beyond the house of the pretty girl

..

.. Script truncations

..

Another thing that sets the pilana apart from other particles, is that they are never written in full. Whether appearing as affixes or independent words, the vowels are always dropped.

The letter "y" represents alfe and the letter "h" represents "alna".

..

..... Punctuation and page layout

..

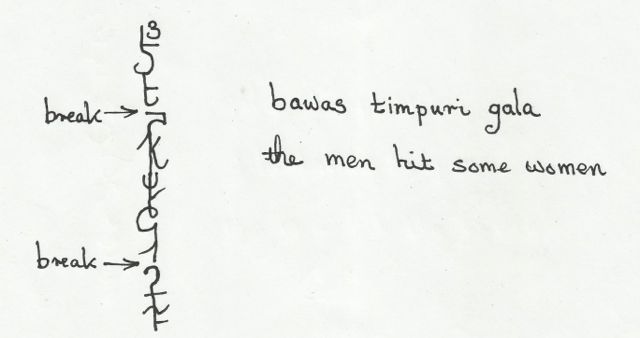

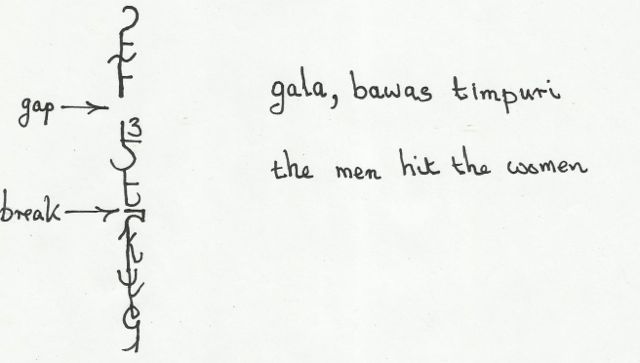

The letters in a word are always contiguous, that is there is always a line running right through the word. Writing is firstly from top to bottom and secondly from left to right.

Between words there is a small break in the line. See the figure below ...

..

..

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, this small break would be indicated by dù

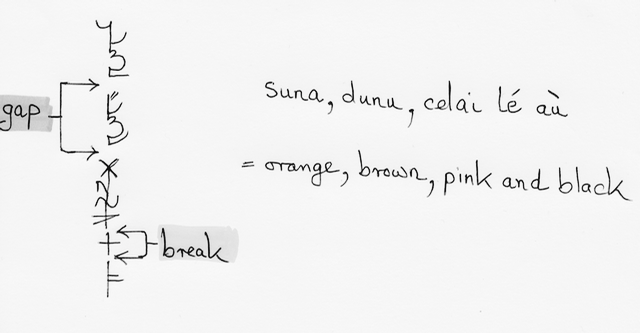

Between some words there is a gap. This represents a pause. A pauses in English is represented by a comma, a colon or a semicolon. Whenever an orator draws breath, this will be reflected in the writing by a gap. Also there are occasions where the grammar of béu demands a gap. When such a gap is required I will represent in in my transcription as an inter word dot. For example ... ‘’’suna . dunu . celai lé àu’’’ = orange, brown, pink and black

Presumable in English, commas originally were always used for pauses in speech. However nowadays in English many pauses are not represented in any way (presumably in these cases when it is not necessary for reading comprehension). Also in English, in a surprising amount of text commas are found where they shouldn't be. In béu gaps in a textblock have a one-to-one correspondence to a pause in speech.

*When listing items, béu is similar to English ... there is pause between every item except the last two items. Between these items, béu has lé, English has "and".

..

..

..

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, the gap is indicated by saying ???

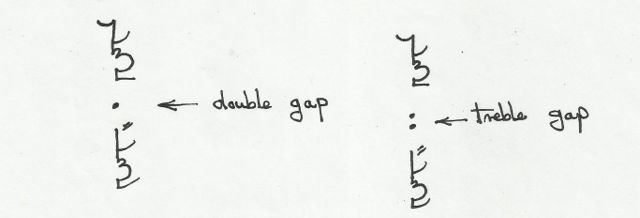

Single gaps are very common. Occasionally you can have "double gaps" and even "treble gaps". These rare creatures represent "pregnant pauses" which are sometimes used for comic effect.

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, a "double gap" is rendered by bauva ??? , a treble gap by baiba ???.

Note the single point used in the "double gap" and the pair of points used in the "treble gap".

..

..

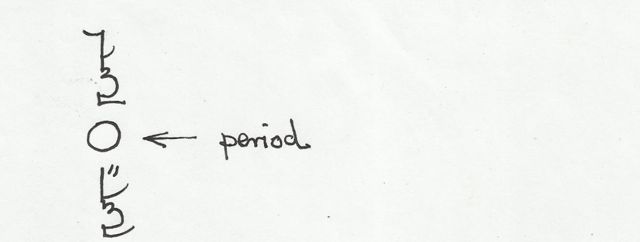

There is also a punctuation mark called the "sunmark" ( kòi = sun ). This is basically a full-stop. The "sunmark" has double the diameter of omba (omba means "circle" and is used as a decimal point).

..

..

There are also punctuation marks called "moonmark" ( dèu = moon ). These are basically brackets. The opening one is called "moonmark" damau and the closing one is called "moonmark" dagoi. Direct speech is enclosed in "moonmarks". These bits of direct speech are also highlighted. Usually the first speaker's words are highlighted in blue and the second speaker's words are highlighted in yellow. The highlighted area is lozenge shape. Every "textblock" the protagonists are reset ??. In a story, after the scene is set ... that is the time of speaking and the identity of the speakers have been established, then their names are dropped from the text and the kloi "speak" is also dropped. However somebody reading the text out loud would give this information from their understanding of the situation.

..

..

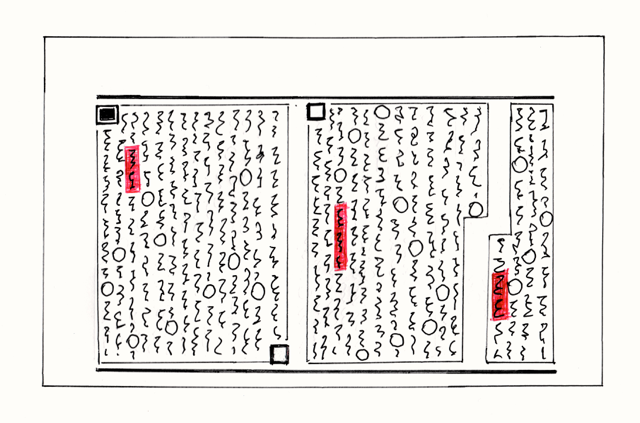

In a normal narrative, everything is written in "textblocks".

(Please note ... the light lines surrounding the "textblocks" are not real. They are just there to assist me drawing)

..

This is the first page in a "chapter". Notice the symbol at the top left hand side of the first "textblock". This is called a "heavy tile".

Textblocks fit in between "rails" about 4 inches apart. The width of a block should be between 60% and 90% * of the block height. Of course it is best to start a new block when the scene of the narrative changes or there is some discontinuity of the action, but this is not always possible. Then you just must arbitrarily split the text into two blocks. The standard practice is to stretch the text a bit so that the tops and bottoms of every column line up with their neighbours. XXXXXX

There is no way to split a word between two lines (as we can do in the West by using two hyphens). A "sunmark" must be next to the last word in a sentence (it can not go to the start of a new column by itself) However if a "sunmark" fall next to the bottom rail, then the next column will begin with a "sunmark". This is purely due to a love of symmetry.

The first text block starts at the top left (as you would expect). The second textblock starts below where the first text block stops. In fact the vertical space between the stop and the start of the two textblocks is equal to the horizontal "interblockspace" (see the figure above).

If the last "sunmark" of a "textblock" falls next to the bottom rail (as indeed happens with the very first "textblock" of the "chapter", then this "sunmark" is changed into a symbol called a "bottom tile". If a "textblock" ends in a "bottom tile", then what is called a "top tile" will appear before the first word of the next "textblock". This is purely due to a love of symmetry. Note that the "top tile" is exactly the same as the "bottom tile". (Actually in modern printing techniques, the text in complete "textblocks" can be stretched to prevent the final "sunmark" falling on the bottom rail)

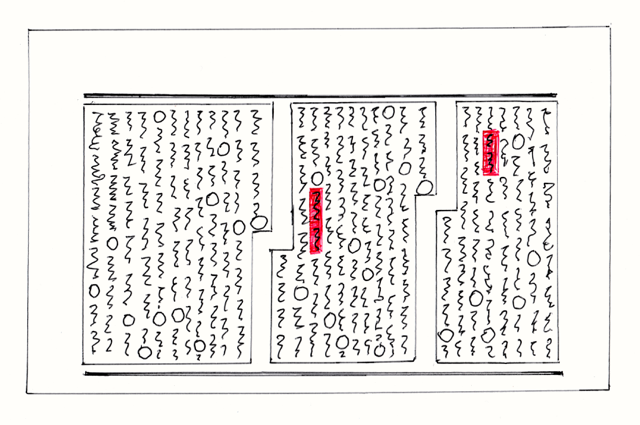

When you come to the end of the page (you will have some sort of margin of course and not go all the way to the edge), you simply continue the block on the LHS of the next rail (or page). Below is the second page of the chapter. This page continues on from the page above.

..

..

In every textblock, one word or short noun phrase is highlighted in red. The shape of the highlighted area is rectangular with rounded edges. Usually a noun is chosen and the more iconic the better. Statistically these highlighted words tend to come towards the beginning of the "textblock".

..

There are two sizes for books. For all hardback books the size is about 8 inches by about 11 inches. For all paperback books the size is about 5 inches by about 8 inches. They are stored as shown in the figure below.

..

..

Unlike books produced in the West, these books are held with the spine horizontal when being read. The hardback page has two "rails" per page (i.e. three dark lines).

On the paperback book, the title is written on the spine and on the front of the book. On the hardback book the title is written on the front, also there is a flap that slides into the spine. However when the book is stored on a shelf, it is pulled out and hangs down. Hence the hardback books can be easily located, even when they are in the bookshelf.

A book will be divided into chapters. A chapter will have a number and usually a title as well. Either at the end of the book or just after the chapter, there will be a page, in which all the highlighted words for a chapter are listed in order. Instead of referencing things by page number, things are reference by chapter and textblock (indictated by the highlighted word(s) ).

Any particular word in a book can be reference by 5 parameters ...

1) "title of book"

2) number of the chapter

3) the highlighted word(s)

4) the number of the sunmarks counted. Actually they are counted backwards ... from the final "sunmark" of the "textblock". Note ... all "sunmarks" are counted, even the ones next to the top rail.

5) the number of the word. This is also counted backwards (i.e. the final word of the sentence is word "1" ... and so on)

* Occasionally very narrow blocks can not be avoided. And of course in mathematical/scientific tracts the tracts are all over the place ... interspersed with diagrams and what have you.

..

..... Uncountable Nouns

..

For uncountable nouns ( sand fandaunyo ) as opposed to countable nouns ( brick fandaunyo ) the construction is a bit different. See below ...

..

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| --------------- | ------------- | ---------------- | ------------- | ----------------- | ------------------- |

| holder | head | adjective | magnifier | determiner | relative clause |

| hua | saidau | hè |

..

For this construction there is no specifier slot or number slot but there is a holder slot

However this "holder" can actually be a NP in itself. Take for example ...

túa hoŋko ʔazwo pona dí = two cups of this hot milk

the "holder" here is túa hoŋko

Note ... even though we have no word "of" ... there is no ambiguity. If the above was two fandaunyo, there would either be a pause between hoŋko and ʔazwo (for example if one was A and one was the O argument), or they would be separated by "and" lé if they were separate fandau.

In this respect béu takes after Indonesian. For example ... five big bags of this black rice = lima tas besar beras hitam ini (literally ... five bag big rice black this)

(5 bag big) (rice black this) .... Usually languages have a linker, particular when the phrases are long. For example Chinese "de", English "of", Japanese "no". béu has no linker (similar to Indonesian) ... (however à or fí could be pressed into service if needed ??? )

(SideNote) ... ʔazwe = to suck ... ʔazweye = to suckle, to offer the breast

Another way in which this construction differs from a "brick" fandaunyo is that there is a magnifier slot. This can be filled with just one word ... well two words if you count hè's derived polar opposite uhe as a separate word.

Now as hè also qualifies other parts of speech, we have some ambiguity here. For example ...

moze pona hè can mean either a lot of hot water or very hot water. One can disambiguate by saying moze pona hè . moze hè / moze pona . moze hè meaning a lot of hot water or moze pona hè . pona hè / moze pona . pona hè meaning very hot water.

..

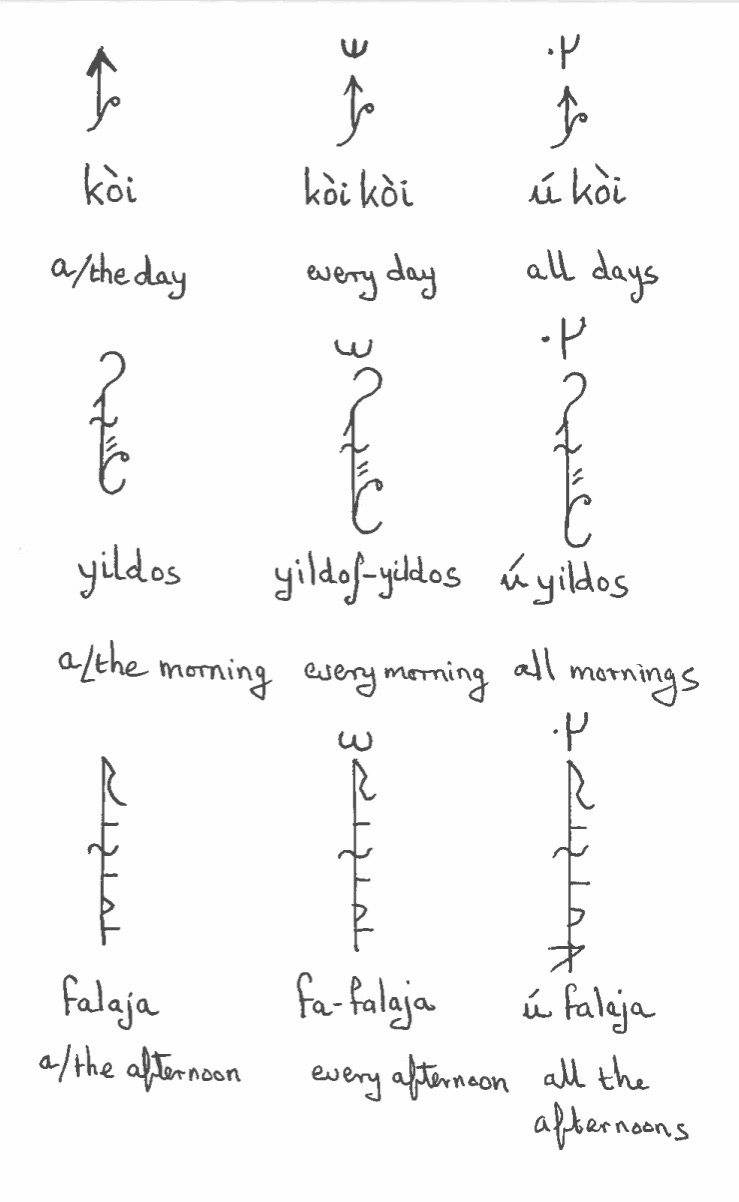

..... Noun totality ... collective and individually

..

Sometimes we want to talk about all members of the category "noun" acting (or being acted upon) COLLECTIVELY.

For this we use the particle ú before the plural of the noun. For example ...

moltai = a/the doctor

moltai.a = doctors

ú moltai = all doctors

Note ... the same word, when appended to a noun, means "the whole" or "entire". For example ...

falaja ú = all morning

..

The opposite of the above, is when all members of the category "noun" is acting (or is being acted upon) INDIVIDUALLY.

By doubling the noun (or the first part of a noun) you give what can be called a distributive meaning.

Some examples ...

kòi = day

kòi kòi = every day

moltai = doctor

moltai moltai = each doctor

falaja = afternoon

fa falaja = every afternoon

Notice that for words over two syllables, only the first syllable is prefixed.

..

The "word-hood" of these duplications is murky. I am writing them here as two separate words ... i.e. fa falaja. But maybe fafalaja or fa-falaja would be more appropriate.

Single syllable words retain there tone when duplicated ... which indicates two separate words. However you also get phonological processes that are usually only word internal. That is to say, these structures show "sandhi".

For example ...

yildos yildos (every morning) would be pronounced / jildoʃ jildos /

bàu bàu (every man) could be pronounced / bàu vàu /

Anyway ... these constructions are never written out in full. Instead a special symbol is placed above the simple noun. This symbol can vary a bit, depending on the font being used : it can vary from a lower half circle bisected by a vertical stroke to a shape that looks a bit like the Arabic shaddah.

For example ...

It some contexts, semantically, it does not matter whether the individual or the collective form is used. When this is the case, the default choice is "individual" structure. ú tends to be used with tangible nouns more, it is hardly ever used with nouns denoting periods of time.

Note (as in English) the plural verb form is used for the collective structure, the singular verb form for the individual structure. For example ...

ú bàu súr = all men are

bàu bàu sór = every man is

TO THINK ABOUT ...

?à ?à bàu hù ?ís = any man that you want ( ?ís ... "you would want" ???? )

?ài ?ài bàu hù ?ís = any men that you want

?ài bàu = some men

..

..... lé .... lú .... lò

..

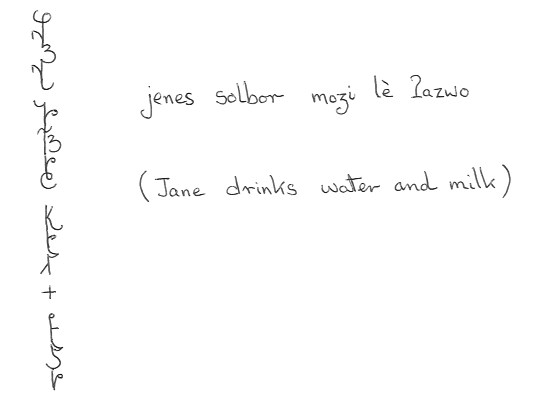

Earlier we have seen that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilana affixed to them. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilana then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

jonos jenes solbur moʒi = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of an affixed pilana, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lé should be placed between them. For example ...

jenes solbori moʒi lé ʔazwo = "Jane drank water and milk"

jonos jenes bwuri hói sadu lé léu ʔusʔa = John and Jane saw two elephants and three giraffes.

[ Compare the above two examples to só jono jene solbori moʒi = Jane's John drank water ... i.e. The John that is in a relationship with Jane, drank water ]

This word is that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

The following construction is also found.

lé moʒi lé ʔazwo = "both water and milk"

The above construction emphasizes the "linking" word lé

Another linking word is lú meaning "or".

jenes blor solbe moʒi lú ʔazwo = "Jane can drink water or milk"

The following construction is also found.

lú moʒi lú ʔazwo = "either water or milk"

The above construction emphasizes the "linking" word lú

There is another word that corresponds to the English "or". This is ʔala and it is a question word. For example ...

ʔís moʒi ʔala ʔazwo = "would you want water or milk"

And the answer expected of would be either "water" or "milk"

Say you were asking somebody if they were thirsty and you had only water or milk to give them. Then you would say ... ʔís moʒi lú ʔazwo @

The expected answer to the above question would be either "yes" or "no" (as is always the case when you have @ ( @ is pronouced a bit like ʔai but has contour tone instead of a normal high tone, it has a special symbol and I am using "@" to represent this symbol in my transliteration)).

Now if the question was "would you want water or milk, or both" you should say ...

ʔís moʒi ʔala ʔazwo ʔala leume

But sometimes (either because of the laziness of the speaker or because the likelyhood was not considered) ... ʔís moʒi ʔala ʔazwo ʔala leume comes out as ʔís moʒi ʔala ʔazwo.

So ʔís leume (I would like both) is an acceptable answer to the question ʔís moʒi ʔala ʔazwo

If the questioner would like to rule out the answer ʔís leume he would use the construction .

ʔís ʔala moʒi ʔala ʔazwo

So ʔala before the first item does exactly the same as lé or lú before the first item : it emphasizes the linking word.

..

... "no"

..

In béu, jù corresponds to "no".

"neither water nor milk" would be translated as jù moʒi jù ʔazwo

..

... lists

..

So far we have restricted ourselves to two items. We can summarize the system for two items as below ...

..

| lé | giving | 2 | items | |||||

| lú | giving | 1 | item | ..... | ʔala | asking for | 1 | item |

| jù | giving | 0 | items |

..

However we can join up more than two items. When more than two items are joined by the above 4 linking words, it is considered good style to have the linking word before the first item and the last item, before each item (except the first and the last) should be a slight pause (I call it a gap ... see "punctuation and page layout" earlier on this page).

For example ...

jenes bwori lé hói sadu _ léu ʔusʔa _ uga moŋgo lé ilda gaifai falaja dí = Jane saw two elephants, three giraffes, four gibbons and five flamengos this morning.

..

... other

..

lò = other

lòi = others

kyulo = again

welo = otherwise

..

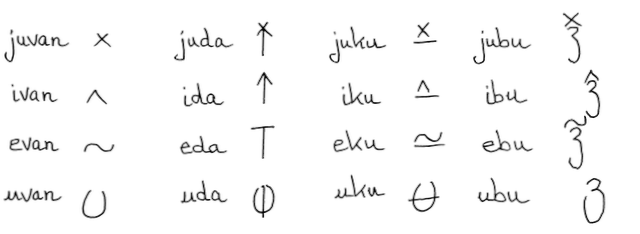

..... Correlatives

..

| juvan | nothing | juda | nowhere | juku | never | jubu | nobody |

| ivan | anything | ida | anywhere | iku | anytime | ibu | anybody |

| evan | something | eda | somewhere | eku | sometime | ebu | somebody |

| uvan | everything | uda | everywhere | uku | always | ubu | everybody |

These correlatives are always written in their shorthand form. See the chart above.

The first column is a contraction of jù fanyo, í fanyo, é fanyo and ù fanyo (fanyo = thing)

The second column is a contraction of jù dá, í dá, é dá and ù dá (dá = place)

The third column is a contraction of jù kyù, í kyù, é kyù and ù kyù (kyù = time/occasion)

The last column is a contraction of jù glabu, í glabu, é glabu and ù glabu (glabu = person)

The non-contracted forms are still used, usually when emphasis is wanted.

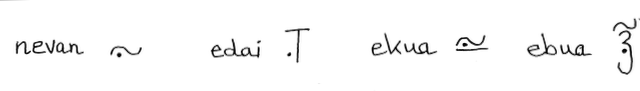

There is another row in the above table.

This is the plural equivalent of the third row of the table above. The emphatic form of the above series would be ...

è fanyo, è dá, è kyù and è glabu .... if these elements were under* the main verb, it would be more normal to use ...

fanyoi, nò dá, nò kyù and glabua .... and actually, if any word from the third row of the main table came under the main verb, you could just use ...

fanyo, dá, kyù and glabu ... in this position you have probably a 50% chance of coming across evan and a similar chance to come across fanyo ... the same with eda, eku and ebu.

One interesting point is ... well for example ubu can mean "each person" and "all the people". If ubu was the S or A argument there could be one of two verbs in a SVC. One would have the meaning "to do together"/"to cooperate" and the other would have the meaning "to work alone". If ubu was the O argument or has some other roll in the sentence there is a partical that can be put in above* ubu. This particle means something like "individual" or "independent" and would disambiguate the meaning of the béu sentence.

*I was going to say 'after" and "before", however as the béu writing system is vertical I thought I should get in the spirit of things and use "under" and "above".

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences