Music and Story in The World: Difference between revisions

(Added article.) |

m (Elemtilas moved page Music in The World to Music and Story in The World) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 05:46, 17 October 2015

So let's hear some music! First I give a Tsarqan written by the Gnomic composer Tsuutam; then a typical countrydance from Auntimoany; third a piece of artmusic, which in the Eastlands is generally called Gnomic Music; and lastly, an orchstral excerpt from Zandam's Imperiall Garden Musicke. This last, the Imperial Garden Music is played by a large orchestra of many kinds of instruments. In the Eastlands, there are two basic kinds of orchestras, and the principal of them is the orchestra of sweet music. It is best suited for quieter, more modulated music, while the orchestra of strident music is more suited for outdoor festivals and raucous entertainments. Its loud reed and brass instruments rarely find their way into the serious music of the orchestra.

The typical art music orchestra in the Eastlands is mostly winds, and is typically heavy on sweet flutes (also known as blockflutes). The second largest group are the strings, comprised of ranks of lutes. This kind of orchestra is called the orchestra of sweet music on account of it comprising instruments that of softer sound that are capable of great dynamic flexibility. This classical orchestra developed from the consort music played by various Daine nations in the East, and so the instrumentation derives from what they favor. Other musical practices are also heavily influenced by the Daine, such as there being no keyboard instruments and very few instruments made from metal.

Members of the group sit generally upon cushions or low stools arranged comfortably on a rug strewn floor in a semicircle. At the front of the orchestra, are three circular wood framed lithophones. One has stone bars, another wooden bars and the third has bone bars, each chosen for their particular tonal coloration.

Behind them is the flute choir, consisting of as many as 40 instruments: eight each of great bass, bass and tenor and 16 trebles. They're arranged aesthetically with the trebles in the middle and the larger instruments around them and at the ends.

Behind the flutes are the stringed insturments. On the audience's left are two to four viols, and behind them, three zithers and one bass zither. Directly behind the flutes are the lutes: four archlutes (two on either side of the choir), eight principal lutes and eight octave lutes (arranged in front of the larger lutes and directly behind the flutes). Behind them are four hammered dulcimers and four harps. Some of the stringed instruments are strung in gut and others in bronze so there is a marked contrastof soft and loud. To give the bronze strung lutes something of a subdued tone, they can be fitted with soft dampers that take the edge off their tone.

On the left side of the orchestra are the reeds. Behind the great bass and bass flutes are eight chalumeaux: four trebles closest to the edge, then two tenors and two basses. Behind them are four treble cornameuses near the audience,then two tenors and two basses. Next to them are three racketts, two great bass and one tenor. Behind them are two treble, two bass oboes and one shawm. Sometimes the rackett players double on dulcians. These reeds and horns are not really all that loud. The shawm is the loudest instrument in the group, and for this reason, there is only one. The other reeds are fairly quiet and buzzy in nature.

On the right side of the orchestra are the horns. Immediately behind the bass and greatbass flutes are six olifants: two each of treble, tenor and bass. Behind them are three or four treble lisards and then two trumpets in the Daine style. Between them and the lutes are two or three bass horns, two bombardons and at the back a matched pair of two mammoth horns.

At the very back are the drums. On either side are the huge bass and tenor drums (like huge bodhrans); in the middle, three or four normal sized frame drums, iron cow bells, sistrums and a jingling crescent. Other assorted noisemakers may be called for, but these are typical.

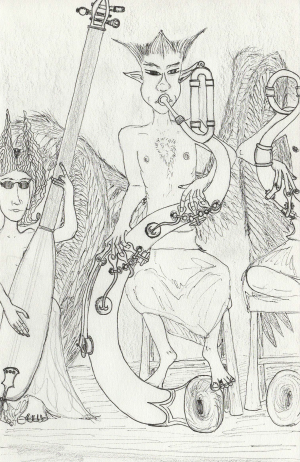

In the picture above, we can see on the left one of the archlutes, a long three-stringed bass boat lute type instrument and next to this the pair of grôtolifant, the big keyed bass horns made from curved sections of bronze tubing. Note that the olifants always come in "right" and "left" horns and each one is curved something like the tusks of the great olifants of the northern steppe.

Storytelling is one of the most commonly practiced arts anywhere in The World. Every community, from the highest of the race of Teyor to the meanest hovels of Hotai, has someone among them who can spin an entertaining tale. But, as with all other arts and crafts, there those whose sole avocation and craft is the knowing and telling of stories. These professional storytellers rely much on the work of the Sawyers, those scholars and philosophers who collect and study stories from all over the world.

The term Sawyery refers to the study of the Old Stories, a set of disjointed but frequently crossculturally parallel or similar stories that tell of the most ancient of days. Typically, they relate to times before history was understood as an entity of its own and recorded for posterity, and thus describe the philosophical Golden Age. Typically, the Wise divide the Old Stories into various types depending upon their focus or intended character.

The philosophical study of the Old Stories is called sawyery and practitioners are called sawyers. Many are the collections of these stories that have been gathered in the libraries of the world. Fine examples can be seen at the great libraries in Alexandria of Kemeteia-Misser, Pretorias of Rumnias and Auntimoany as well. The sawyers' public trust is to preserve and expand collections of Old Stories; collect, collate and index the pronouncements and interpretations of philosophers, priests, and spiritual teachers; and to make available to the people whatever they wish to study from these collections. Therefore, anyone who can read or is accompanied by someone who can read is allowed unrestricted access to a library's collection of Old Stories. Several famous catalogues of Old Stories have been made by sawyers in recent centuries, especially those of Arny and Thompson, sawyers of Auntimoany who devised a topical and cross-referenced indexing system for their collection not only of stories but of the episodes and characters within them. Also well known is Franko Childer, a Husickite sawyer, who catalogued fables and various kinds of folk songs.

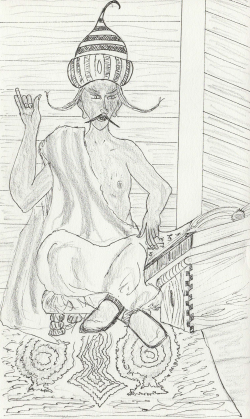

While ordinary story tellers rely on the diligent scholarship of the sawyers, they don't simply repeat stories verbatim. They retell, recombine, come up with wonderful new tales the like of which have never been heard before. Other storytellers keep closer to the old traditions conserved within the works of the sawyers. It is these granthund, or classical story tellers, like the fellow in the picture on the right, that bring the old myths and legends to life.

These granthund have memorised a great treasure trove of old story however, during more formal recitations, such as in the court of a gravio or in the emperor's Palas, it is usual for a large book of story to be placed upon a low stand for the granthund to refer to. By ancient tradition, story tellers always sit upon a low, comfortable stool and this is usually located upon a nicely woven rug, and they may only be served their food and drink upon earthenware vessels. This, they say, is a reminder to their own humility, for story should serve the good all folk of good will, and not serve the exaltation of the storyteller. Even so, some famous granthund are recorded in the annals of kingdoms and countryside inns, perhaps the best known of which Uthmanda, a nineteenth century granthund well known for his animated style and broad repertoire. It was said of him that he could hear a story of any length for the first time and ever after could retell the story without losing one single word or nuance of meaning.