Béu : Chapter 5: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== ..... Some valency changing operations== | |||

THE 37 SPECIAL VERBS MUST COME BEFORE THIS. | |||

=== ... Valency ... 2 => 1=== | |||

.. | |||

The passive is normally formed by infixing '''-w-''' just before the final vowel. For example ... | |||

'''kó''' = to see | |||

'''(pás) kár gì''' = I see you | |||

'''pás kár gì''' = I myself see you | |||

'''(pà) kowar''' = I am seen | |||

'''(pà) kowar hí gì''' = I am seen by you | |||

'''pà kowara''' = I myself am being seen | |||

'''kowari''' = I have been seen | |||

'''kowaru''' = I have not yet been seen | |||

'''taiku kowar''' = I was seen | |||

'''jauku kowar''' = I will be seen | |||

etc. etc. | |||

The subject of the active clause, can be included in the passive clause as an afterthought if required. '''hí''' is a normal noun meaning "source". However it also acts as a particle (prefix) which introduces the agent in a passive clause. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| the infinitive | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| perfect | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| infinitive of passive | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| perfect of passive | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| passive participle | |||

|align=center| | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kludau''' | |||

|align=center| to write | |||

|align=center| '''kludori''' | |||

|align=center| he has written | |||

|align=center| '''kludwau''' | |||

|align=center| to be written | |||

|align=center| '''kludwori''' | |||

|align=center| it has been written | |||

|align=center| '''kludwai''' | |||

|align=center| written | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kó''' | |||

|align=center| to see | |||

|align=center| '''kori''' | |||

|align=center| she has seen | |||

|align=center| '''kowa''' | |||

|align=center| to be seen | |||

|align=center| '''kowori''' | |||

|align=center| she has been seen | |||

|align=center| '''kowai''' | |||

|align=center| seen | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''timpa''' | |||

|align=center| to hit | |||

|align=center| '''timpori''' | |||

|align=center| he has hit | |||

|align=center| '''timpwa''' | |||

|align=center| to be hit | |||

|align=center| '''timpwori''' | |||

|align=center| he has been hit | |||

|align=center| '''timpwai''' | |||

|align=center| hit | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''poʔau''' | |||

|align=center| to cook | |||

|align=center| '''poʔori''' | |||

|align=center| she has cooked | |||

|align=center| '''poʔawa''' | |||

|align=center| to be cooked | |||

|align=center| '''poʔawori''' | |||

|align=center| it has been cooked | |||

|align=center| '''poʔawai''' | |||

|align=center| cooked | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

When the final consonant is '''w y h''' or '''ʔ''' the passive is formed by suffixing '''-wa''' | |||

In monosyllabic words, it is formed by suffixing '''-wa'''. | |||

Note ... when '''wa''' is added to a word ending in '''au''' or '''eu''', the final '''u''' is deleted. | |||

Also note ... these operations can make consonant clusters which are not allowed in the base words. For example, in a root word '''-mpw-''' would not be allowed ( Chapter 1, Consonant clusters, Word medial) | |||

.. | |||

=== ... Valency ... 1 => 2=== | |||

.. | |||

Now all verbs that can take an ergative argument can undergo the 2=>1 transformation. | |||

There also exists in '''béu''' a 1=>2 transformation. However this transformation can only be applied to a handful of verbs. Namely ... | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoime''' | |||

|align=center| to be happy, happyness | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimora''' | |||

|align=center| he is happy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimye''' | |||

|align=center| to make happy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimyana''' | |||

|align=center| pleasant | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''heuno''' | |||

|align=center| to be sad/sadness | |||

|align=center| '''heunora''' | |||

|align=center| she's sad | |||

|align=center| '''heunyo''' | |||

|align=center| to make sad | |||

|align=center| '''heunyana''' | |||

|align=center| depressing | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''taudu''' | |||

|align=center| to be annoyed | |||

|align=center| '''taudora''' | |||

|align=center| he is annoyed | |||

|align=center| '''tauju''' | |||

|align=center| to annoy | |||

|align=center| '''taujana''' | |||

|align=center| annoying | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''swú''' | |||

|align=center| to be scared, fear | |||

|align=center| '''swora''' | |||

|align=center| she is afraid | |||

|align=center| '''swuya''' | |||

|align=center| to scare | |||

|align=center| '''swuyana''' | |||

|align=center| frightening, scary | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''canti''' | |||

|align=center| to be angry, anger | |||

|align=center| '''cantora''' | |||

|align=center| he is angry | |||

|align=center| '''canci''' | |||

|align=center| to make angry | |||

|align=center| '''cancana''' | |||

|align=center| really annoying | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''yodi''' | |||

|align=center| to be horny, lust | |||

|align=center| '''yodora''' | |||

|align=center| she is horny | |||

|align=center| '''yoji''' | |||

|align=center| to make horny | |||

|align=center| '''yojana''' | |||

|align=center| sexy, hot | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''gái''' | |||

|align=center| to ache, pain | |||

|align=center| '''gayora''' | |||

|align=center| he hurts | |||

|align=center| '''gaya''' | |||

|align=center| to hurt (something) | |||

|align=center| '''gayana''' | |||

|align=center| painful <sup>*</sup> | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''gwibe''' | |||

|align=center| to be ashamed/shame/shyness | |||

|align=center| '''gwibora''' | |||

|align=center| she is ashamed/shy | |||

|align=center| '''gwibye''' | |||

|align=center| to embarrass | |||

|align=center| '''gwibyana''' | |||

|align=center| embarrassing | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''doimoi''' | |||

|align=center| to be anxious, anxiety | |||

|align=center| '''doimora''' | |||

|align=center| he is anxious | |||

|align=center| '''doimyoi''' | |||

|align=center| to cause anxiety, to make anxious | |||

|align=center| '''doimyana''' | |||

|align=center| worrying | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''ʔica''' | |||

|align=center| to be jealous, jealousy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔicora''' | |||

|align=center| she is jealous | |||

|align=center| '''ʔicaya''' | |||

|align=center| to make jealous | |||

|align=center| '''ʔicayana''' | |||

|align=center| causing jealousy | |||

|} | |||

'''ʔoimor''' would mean "he is happy by nature". All the above words take this sense when the "'''a'''" of the present tense is dropped. | |||

The above words are all about internal feelings. | |||

The third column gives a transitive infinitive (derived from the column two entry by infixing a '''-y-''' before the final vowel). | |||

The fourth column gives an adjective of the transitive verb (derived from column three entry by affixing a '''-ana''' ... the active participle). | |||

When the final consonant is '''ʔ j c w''' or '''h''' the causative is formed by suffixing '''-ya'''. | |||

Also when the verb is a monosyllable, the causative is formed by suffixing '''-ya'''. | |||

Note ... when '''ya''' is added to a word ending in '''ai''' or '''oi''', the final '''i''' is deleted. | |||

Note ... when '''y''' is infixed behind '''t''' and '''d''' : '''ty''' => '''c''' and '''dy''' => '''j''' | |||

----- | |||

There is one other word that follows the same paradigm as the 10 words above. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''jùa''' | |||

|align=center| to know | |||

|align=center| '''jor''' | |||

|align=center| he knows | |||

|align=center| '''juya''' | |||

|align=center| to tell | |||

|align=center| '''juyori''' | |||

|align=center| she has told | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

Normally in '''béu''', to make a nominally intransitive verb transitive, it doesn't need the infixing of -'''y'''. All it needs is the appearance of an ergative argument. For example ... | |||

'''doika''' = to walk | |||

'''doikor''' = he walk | |||

'''ós doikor''' the pulp mill = he runs the pulp mill | |||

'''doikyana''' = management ??? | |||

.. | |||

<sup>*</sup>You would describe a gallstone as '''gayana'''. However you would describe your leg as '''gaila''' (well provided you didn't have a chronic condition with your leg) | |||

.. | |||

=== ... Concatenation of the valency changing derivations ... 1 => 2 => 1 and 2 => 1 => 2=== | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoime''' | |||

|align=center| = to be happy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimye''' | |||

|align=center| = to make happy | |||

|align=center| '''ʔoimyewa''' | |||

|align=center| = "to be made to be happy" or, more simply "to be made happy | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''fàu''' | |||

|align=center| = to know | |||

|align=center| '''fa??''' | |||

|align=center| = to tell | |||

|align=center| '''fa ??''' | |||

|align=center| = | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''timpa''' | |||

|align=center| = to hit | |||

|align=center| '''timpawa''' | |||

|align=center| = to be hit | |||

|align=center| '''timpawaya''' | |||

|align=center| = to cause to be hit | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

Semantically '''timpa''' is direct action (from agent to patient). Whereas '''timpawaya''' is indirect, possibly involving some third party between the agent and the patient and/or allowing some time to pass, between resolving on the action and the action being done unto the patient. | |||

.. | |||

== ..... A bit about adverbs== | |||

If an adjective comes immediately after a verb (which it normally would) it is known to be an adverb. For example '''saco''' means "slow" but if it came immediately after a verb it would be translated as "slowly". However if we add '''-we''' to it so we get the form '''sacowe''' the adverb can move around the utterance ... wherever it wants to go. ..... SIMILAR TO "To come and go" + "to give" ... LIGHT GREEN HI-LIGHT | |||

----- | |||

'''-we''' can also be affixed to a noun and also produce an adverb. For example ;- | |||

'''deuta''' means "soldier" | |||

'''deutawe''' means "in the manner of a soldier" | |||

as in '''doikora deutawe''' = he is walking like a soldier ... of course the -'''we''' is not dropped when the adverb directly follows the verb. | |||

----- | |||

Now going back to the 6 "co-ordinate" particles '''máu gòi cè dùa bene komo''' in the previous section. Basically a word ending in one of these particles, is an adjective. For example | |||

However sometimes TABLE'''mau''' is an adverb. When it is, it must come directly after the verb (that is ... we can not add '''-we''' and move it from its position immediately behind the verb, as can be done with other adjectives active as adverbs). For example ... | |||

The monkey eats an apple on the table ... ambiguous in English ... not ambiguous in '''béu''' | |||

MONKEY EATS TABLEmau APPLE | |||

MONKEY EATS APPLE TABLEmau | |||

------ | |||

So that is basically all there is to adverbs. In the Western linguistic tradition many other words are classified as adverbs. Words such as "often" and "tomorrow" etc. etc. | |||

In the '''béu''' linguistic tradition all these words are classified as particles, a hodge podge collection of words that do not fit into the usual word classes. | |||

.. | |||

== ... Parenthesis== | |||

.. | |||

'''béu''' has two particles that indicate the start of some sort of parenthesis. In a similar way to a mathematical formula, where brackets mean that the arguments within the brackets should be evaluated first, the two '''béu''' particles indicate that the immediately following clause should be processed (by the brain) before arguments outside of the parenthesis are considered. | |||

.. | |||

=== . '''tà''' ... the full clause particle=== | |||

.. | |||

This is basically the same as "that" in English, when "that" introduces a complement clause. For example ... | |||

"He said THAT he was not feeling well" | |||

Notice that "he was not feeling well" is complete in itself, it is a self-contained clause. | |||

.. | |||

=== . '''ʔà''' ... the gap clause particle=== | |||

.. | |||

This is basically the same as "what" in English, in such sentences as ... | |||

"WHAT you see is WHAT you get"<sup>*</sup> | |||

Notice that "you see" and "you get" are not complete clauses, there is a "gap" in them. | |||

The phase "WHAT you see", (to return to the mathematical analogy again) may be thought of as a "variable". in this case, the motivation for using a "variable", is to make the expression "general" rather than "specific". (Being general it is of course more worthy of our consideration). Other motivations for using a "variable" is that the actual argument is not known. Yet another is that even though the particular argument is known, it is really awkward to specify satisfactorily. | |||

EXAMPLE | |||

Another way to think about the '''ʔà''' construction, is to think of it as a "nominaliser", a particle that turns a whole clause into a noun. To use the example from just above .... | |||

"see" is an intransitive verb with two arguments. To replace one of these arguments by '''ʔà''' is like defining the missing argument in terms of the rest of the clause i.e. it changes a clause into a constuction that refers to one argument of that clause. | |||

=== . Gap clause particles in other languages=== | |||

There is no generally agreed upon term for the type of construction which I am calling "gap clause" here. Dixon calls it a "fused relative", Greenberg calls it a "headless relative clause". I don't like either term. A fused relative implies that a generic noun (i.e. "thing" or "person") somehow got fused with a relativizer. This certainly never happened although this type of clause can be rewritten as a generic noun followed by a relativizer. As for "headless" relative clause ... well I think the type of clause that we are dealing with is in fact more fundamental then a relative clause, so I would not like to define it in terms of a relative clause. | |||

My thoughts on this type of clause are ... | |||

Well "what" was firstly a question word. So you have expressions like "Who fed the cat" | |||

Then of course it is natural to have an answer like "I don't know who fed the cat" | |||

Now the above sentence is similar to "I don't know French" or "I don't know Johnny". | |||

Now you see the expression "who fed the cat" fills the slot usually occupied by a noun in an "I don't know" sentences. | |||

So "who fed the cat" started to be thought of as a sort of noun. | |||

Now from the "know (neg)" beachhead<sup>*</sup>, the usage would have spread to "know" and also the such words that have "knowing" as an essential part of their meaning. Words such as "remember", "report" etc. etc. | |||

<sup>*</sup>I call "know (neg)" a "beachhead"<sup>**</sup>. A beachhead is a usage(and/or the act or situation behind that usage) that facilitates the meaning of a word to spread. Or the meaning of an expression to spread. A beachhead can be defined simply as an expression, but sometimes some background as to the speakers environment has to be given. For example suppose that one dialect of a language was using a word to mean "under", but this same word meant "between/among" in all other dialects. Now suppose you did some investigating and found that all other dialects of this language was spoken on the steppes and their speakers made a living by animal husbandry. However the group which diverged from the others had given up the nomadic life and settled down in a lush river valley. In this valley their main occupation was tending their fruit orchards. | |||

It could be deduced that the change in meaning came about by people saying ... "Johnny is among the trees". Now as the trees were thick on the ground and had overspreading branches, this was reanalysed to mean "Johnny is under the trees". Hence I would say ... | |||

The beachhead of word "x" = "between" to word "x" = "under" was the expression "among the trees" (and in this case a bit of background as to the "culture" of the speakers would be appropriate). ... OK ? ... understood ? | |||

For an expressing to become a beachhead, it must, of course, be used regularly. | |||

ASIDE ... I have thought about counting rosary beads as a possible beachhead that changed the meaning of "have", in Western Europe, from purely "possession" to a perfect marker. This is just (fairly ?) wild conjecture of course. (The beachhead expression being "I have x beads counted" with "counted" originally being a passive participle) | |||

I am digressing here ... well to get back to "who fed the cat". We had it being considered a sort of noun. Presumably it was at one time put directly after a noun in apposition (presumably with a period of silence between the two) and qualified the noun. Then presumably they got bound closer together, the gap was lost, and this is the history of one form of relative clause in English. | |||

<sup>**</sup>Actually I would have liked to use the term pivot here. However this term has already been taken. | |||

From the dictionary | |||

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 1. A position on an enemy shoreline captured by troops in advance of an invading force | |||

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 2. A first achievement that opens the way for further developments. | |||

----- | |||

There are 4 relativizers ... '''ʔá''', '''ʔái''', '''ʔáu''' and '''ʔaja'''. (relativizer = '''ʔasemo'''-marker) | |||

'''ʔasemo''' = relative clause. | |||

It works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. The '''béu''' relativisers is '''ʔá'''. Though '''ʔái''', '''ʔáu''' and '''ʔaja''' also have roles as relativisers. | |||

The main relativiser is '''ʔá''' and all the '''pilana''' can occur with it (well all the '''pilana''' except '''ʔe'''. '''ʔaí''' is used instead of * '''ʔaʔe'''). | |||

The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its '''pilana''' on the suffixed to the relativizer. For example ;- | |||

'''glà ʔá bwás timpori rà hauʔe''' = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful. | |||

'''bwá ʔás timpori glà rà ʔaiho''' = The man that hit the woman is ugly. | |||

The same thing happens with all the '''pilana'''. For example ;- | |||

the basket '''ʔapi''' the cat shat was cleaned by John. | |||

the wall '''ʔala''' you are sitting was built by my grandfather. | |||

the woman '''ʔaye''' I told the secret, took it to her grave. | |||

the town '''ʔafi''' she has come is the biggest south of the mountain. | |||

the lilly pad '''ʔalya''' the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond. | |||

the boat '''ʔalfe''' you have just jumped is unsound | |||

'''báu ʔás timpori glá rà ʔaiho''' = The man that hit the woman is ugly. | |||

* '''nambo ʔaʔe''' she lives is the biggest in town. | |||

'''báu ʔaho ò''' is going to market is her husband. | |||

the knife '''ʔatu''' he severed the branch is a 100 years old | |||

'''báu ʔán''' dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police<sup>*</sup> | |||

The old woman '''ʔaji''' I deliver the newspaper, has died. | |||

The boy '''ʔaco''' they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand. | |||

<sup>*</sup>Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. '''n''' marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause. | |||

--------- | |||

As you see in above, '''ʔa''' in the form * '''ʔaʔe''' is not allowed. Instead you must use '''ʔaí'''. | |||

The use of '''ʔái''' and '''ʔàu''' as relativizers are basically the same as the use of "where" and "when" in English. These two can combine with two of the '''pilana'''. | |||

'''?aifi''' = from where, whence | |||

'''?aiye''' = to where, hence | |||

'''?aufi''' = from when, since | |||

'''?auye''' = to when, until | |||

The use of '''ʔaja''' basically is a relativizer for an entire clause instead of just the noun which it follows. | |||

For example ??????? | |||

WITH SPACE AND TIME | |||

PLURAL FORM | |||

.. | |||

=== ... the NP with the present participle core ??=== | |||

.. | |||

Now the phrase '''jono kludala toili''' is a noun phrase (NP) in which the adjective phrase (AP) qualifies the noun '''jono''' | |||

(Notice that in the clause that corresponds to the above NP, '''jonos kludora toili''' (John is writing the book), '''jono''' has the ergative suffix and the 3 words can occur in any order : with the NP, '''jono''' does not take the ergative suffix and the 3 words must occur in the order shown.) | |||

'''glói''' = to see | |||

'''polo''' = Paul | |||

'''timpa''' = to hit | |||

'''jene''' = Jenny | |||

'''glori polo timpala é''' = He saw paul hitting something | |||

'''glori pà timpala ò''' = He saw me hitting her | |||

'''glori hà (pás) timparwi ò''' = He saw that I had hit her | |||

'''glori jene timpwala''' = He saw Jenny being hit | |||

Now the question is where is this special NP used. Well it is used in situations where English would use a complement clause. For example with '''algo''' meaning "to think about",<sup>*</sup> | |||

1) '''algara jono''' = I am thinking about John. | |||

2) '''algara jono kludala toili''' = I am thinking about John writing a book. | |||

Note ... According to Dixon, the standard English translation of 2) would be "I am thinking about John's writing a book" which I find quite strange even though English is my mother tongue. I have decided to call this sort of construction in '''béu''' a special kind of NP, while Dixon has called the equivalent expression in English the "-ing" type of complement clause. I think this is just a naming thing and doesn't really matter. | |||

<sup>*</sup>"to think (that)" is '''alhu''' in '''béu'''. '''alhu''' also translates "to believe". | |||

.. | |||

== ..... Punctuation and page layout== | == ..... Punctuation and page layout== | ||

Revision as of 03:20, 10 January 2015

..... Some valency changing operations

THE 37 SPECIAL VERBS MUST COME BEFORE THIS.

... Valency ... 2 => 1

..

The passive is normally formed by infixing -w- just before the final vowel. For example ...

kó = to see

(pás) kár gì = I see you

pás kár gì = I myself see you

(pà) kowar = I am seen

(pà) kowar hí gì = I am seen by you

pà kowara = I myself am being seen

kowari = I have been seen

kowaru = I have not yet been seen

taiku kowar = I was seen

jauku kowar = I will be seen

etc. etc.

The subject of the active clause, can be included in the passive clause as an afterthought if required. hí is a normal noun meaning "source". However it also acts as a particle (prefix) which introduces the agent in a passive clause.

| the infinitive | perfect | infinitive of passive | perfect of passive | passive participle | |||||

| kludau | to write | kludori | he has written | kludwau | to be written | kludwori | it has been written | kludwai | written |

| kó | to see | kori | she has seen | kowa | to be seen | kowori | she has been seen | kowai | seen |

| timpa | to hit | timpori | he has hit | timpwa | to be hit | timpwori | he has been hit | timpwai | hit |

| poʔau | to cook | poʔori | she has cooked | poʔawa | to be cooked | poʔawori | it has been cooked | poʔawai | cooked |

..

When the final consonant is w y h or ʔ the passive is formed by suffixing -wa

In monosyllabic words, it is formed by suffixing -wa.

Note ... when wa is added to a word ending in au or eu, the final u is deleted.

Also note ... these operations can make consonant clusters which are not allowed in the base words. For example, in a root word -mpw- would not be allowed ( Chapter 1, Consonant clusters, Word medial)

..

... Valency ... 1 => 2

..

Now all verbs that can take an ergative argument can undergo the 2=>1 transformation.

There also exists in béu a 1=>2 transformation. However this transformation can only be applied to a handful of verbs. Namely ...

| ʔoime | to be happy, happyness | ʔoimora | he is happy | ʔoimye | to make happy | ʔoimyana | pleasant |

| heuno | to be sad/sadness | heunora | she's sad | heunyo | to make sad | heunyana | depressing |

| taudu | to be annoyed | taudora | he is annoyed | tauju | to annoy | taujana | annoying |

| swú | to be scared, fear | swora | she is afraid | swuya | to scare | swuyana | frightening, scary |

| canti | to be angry, anger | cantora | he is angry | canci | to make angry | cancana | really annoying |

| yodi | to be horny, lust | yodora | she is horny | yoji | to make horny | yojana | sexy, hot |

| gái | to ache, pain | gayora | he hurts | gaya | to hurt (something) | gayana | painful * |

| gwibe | to be ashamed/shame/shyness | gwibora | she is ashamed/shy | gwibye | to embarrass | gwibyana | embarrassing |

| doimoi | to be anxious, anxiety | doimora | he is anxious | doimyoi | to cause anxiety, to make anxious | doimyana | worrying |

| ʔica | to be jealous, jealousy | ʔicora | she is jealous | ʔicaya | to make jealous | ʔicayana | causing jealousy |

ʔoimor would mean "he is happy by nature". All the above words take this sense when the "a" of the present tense is dropped.

The above words are all about internal feelings.

The third column gives a transitive infinitive (derived from the column two entry by infixing a -y- before the final vowel).

The fourth column gives an adjective of the transitive verb (derived from column three entry by affixing a -ana ... the active participle).

When the final consonant is ʔ j c w or h the causative is formed by suffixing -ya.

Also when the verb is a monosyllable, the causative is formed by suffixing -ya.

Note ... when ya is added to a word ending in ai or oi, the final i is deleted.

Note ... when y is infixed behind t and d : ty => c and dy => j

There is one other word that follows the same paradigm as the 10 words above.

| jùa | to know | jor | he knows | juya | to tell | juyori | she has told |

..

Normally in béu, to make a nominally intransitive verb transitive, it doesn't need the infixing of -y. All it needs is the appearance of an ergative argument. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikor = he walk

ós doikor the pulp mill = he runs the pulp mill

doikyana = management ???

..

*You would describe a gallstone as gayana. However you would describe your leg as gaila (well provided you didn't have a chronic condition with your leg)

..

... Concatenation of the valency changing derivations ... 1 => 2 => 1 and 2 => 1 => 2

..

| ʔoime | = to be happy | ʔoimye | = to make happy | ʔoimyewa | = "to be made to be happy" or, more simply "to be made happy |

..

| fàu | = to know | fa?? | = to tell | fa ?? | = |

..

| timpa | = to hit | timpawa | = to be hit | timpawaya | = to cause to be hit |

..

Semantically timpa is direct action (from agent to patient). Whereas timpawaya is indirect, possibly involving some third party between the agent and the patient and/or allowing some time to pass, between resolving on the action and the action being done unto the patient.

..

..... A bit about adverbs

If an adjective comes immediately after a verb (which it normally would) it is known to be an adverb. For example saco means "slow" but if it came immediately after a verb it would be translated as "slowly". However if we add -we to it so we get the form sacowe the adverb can move around the utterance ... wherever it wants to go. ..... SIMILAR TO "To come and go" + "to give" ... LIGHT GREEN HI-LIGHT

-we can also be affixed to a noun and also produce an adverb. For example ;-

deuta means "soldier"

deutawe means "in the manner of a soldier"

as in doikora deutawe = he is walking like a soldier ... of course the -we is not dropped when the adverb directly follows the verb.

Now going back to the 6 "co-ordinate" particles máu gòi cè dùa bene komo in the previous section. Basically a word ending in one of these particles, is an adjective. For example

However sometimes TABLEmau is an adverb. When it is, it must come directly after the verb (that is ... we can not add -we and move it from its position immediately behind the verb, as can be done with other adjectives active as adverbs). For example ...

The monkey eats an apple on the table ... ambiguous in English ... not ambiguous in béu

MONKEY EATS TABLEmau APPLE

MONKEY EATS APPLE TABLEmau

So that is basically all there is to adverbs. In the Western linguistic tradition many other words are classified as adverbs. Words such as "often" and "tomorrow" etc. etc.

In the béu linguistic tradition all these words are classified as particles, a hodge podge collection of words that do not fit into the usual word classes.

..

... Parenthesis

..

béu has two particles that indicate the start of some sort of parenthesis. In a similar way to a mathematical formula, where brackets mean that the arguments within the brackets should be evaluated first, the two béu particles indicate that the immediately following clause should be processed (by the brain) before arguments outside of the parenthesis are considered.

..

. tà ... the full clause particle

..

This is basically the same as "that" in English, when "that" introduces a complement clause. For example ...

"He said THAT he was not feeling well"

Notice that "he was not feeling well" is complete in itself, it is a self-contained clause.

..

. ʔà ... the gap clause particle

..

This is basically the same as "what" in English, in such sentences as ...

"WHAT you see is WHAT you get"*

Notice that "you see" and "you get" are not complete clauses, there is a "gap" in them.

The phase "WHAT you see", (to return to the mathematical analogy again) may be thought of as a "variable". in this case, the motivation for using a "variable", is to make the expression "general" rather than "specific". (Being general it is of course more worthy of our consideration). Other motivations for using a "variable" is that the actual argument is not known. Yet another is that even though the particular argument is known, it is really awkward to specify satisfactorily.

EXAMPLE

Another way to think about the ʔà construction, is to think of it as a "nominaliser", a particle that turns a whole clause into a noun. To use the example from just above ....

"see" is an intransitive verb with two arguments. To replace one of these arguments by ʔà is like defining the missing argument in terms of the rest of the clause i.e. it changes a clause into a constuction that refers to one argument of that clause.

. Gap clause particles in other languages

There is no generally agreed upon term for the type of construction which I am calling "gap clause" here. Dixon calls it a "fused relative", Greenberg calls it a "headless relative clause". I don't like either term. A fused relative implies that a generic noun (i.e. "thing" or "person") somehow got fused with a relativizer. This certainly never happened although this type of clause can be rewritten as a generic noun followed by a relativizer. As for "headless" relative clause ... well I think the type of clause that we are dealing with is in fact more fundamental then a relative clause, so I would not like to define it in terms of a relative clause.

My thoughts on this type of clause are ...

Well "what" was firstly a question word. So you have expressions like "Who fed the cat"

Then of course it is natural to have an answer like "I don't know who fed the cat"

Now the above sentence is similar to "I don't know French" or "I don't know Johnny".

Now you see the expression "who fed the cat" fills the slot usually occupied by a noun in an "I don't know" sentences.

So "who fed the cat" started to be thought of as a sort of noun.

Now from the "know (neg)" beachhead*, the usage would have spread to "know" and also the such words that have "knowing" as an essential part of their meaning. Words such as "remember", "report" etc. etc.

*I call "know (neg)" a "beachhead"**. A beachhead is a usage(and/or the act or situation behind that usage) that facilitates the meaning of a word to spread. Or the meaning of an expression to spread. A beachhead can be defined simply as an expression, but sometimes some background as to the speakers environment has to be given. For example suppose that one dialect of a language was using a word to mean "under", but this same word meant "between/among" in all other dialects. Now suppose you did some investigating and found that all other dialects of this language was spoken on the steppes and their speakers made a living by animal husbandry. However the group which diverged from the others had given up the nomadic life and settled down in a lush river valley. In this valley their main occupation was tending their fruit orchards.

It could be deduced that the change in meaning came about by people saying ... "Johnny is among the trees". Now as the trees were thick on the ground and had overspreading branches, this was reanalysed to mean "Johnny is under the trees". Hence I would say ...

The beachhead of word "x" = "between" to word "x" = "under" was the expression "among the trees" (and in this case a bit of background as to the "culture" of the speakers would be appropriate). ... OK ? ... understood ?

For an expressing to become a beachhead, it must, of course, be used regularly.

ASIDE ... I have thought about counting rosary beads as a possible beachhead that changed the meaning of "have", in Western Europe, from purely "possession" to a perfect marker. This is just (fairly ?) wild conjecture of course. (The beachhead expression being "I have x beads counted" with "counted" originally being a passive participle)

I am digressing here ... well to get back to "who fed the cat". We had it being considered a sort of noun. Presumably it was at one time put directly after a noun in apposition (presumably with a period of silence between the two) and qualified the noun. Then presumably they got bound closer together, the gap was lost, and this is the history of one form of relative clause in English.

**Actually I would have liked to use the term pivot here. However this term has already been taken.

From the dictionary

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 1. A position on an enemy shoreline captured by troops in advance of an invading force

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 2. A first achievement that opens the way for further developments.

There are 4 relativizers ... ʔá, ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja. (relativizer = ʔasemo-marker)

ʔasemo = relative clause.

It works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. The béu relativisers is ʔá. Though ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja also have roles as relativisers.

The main relativiser is ʔá and all the pilana can occur with it (well all the pilana except ʔe. ʔaí is used instead of * ʔaʔe).

The noun that is being qualified is dropped from the relative clause, but the roll which it would play is shown by its pilana on the suffixed to the relativizer. For example ;-

glà ʔá bwás timpori rà hauʔe = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful.

bwá ʔás timpori glà rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

The same thing happens with all the pilana. For example ;-

the basket ʔapi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ʔala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman ʔaye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town ʔafi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad ʔalya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

the boat ʔalfe you have just jumped is unsound

báu ʔás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

- nambo ʔaʔe she lives is the biggest in town.

báu ʔaho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife ʔatu he severed the branch is a 100 years old

báu ʔán dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police*

The old woman ʔaji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy ʔaco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

*Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. n marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause.

As you see in above, ʔa in the form * ʔaʔe is not allowed. Instead you must use ʔaí.

The use of ʔái and ʔàu as relativizers are basically the same as the use of "where" and "when" in English. These two can combine with two of the pilana.

?aifi = from where, whence

?aiye = to where, hence

?aufi = from when, since

?auye = to when, until

The use of ʔaja basically is a relativizer for an entire clause instead of just the noun which it follows.

For example ???????

WITH SPACE AND TIME

PLURAL FORM

..

... the NP with the present participle core ??

..

Now the phrase jono kludala toili is a noun phrase (NP) in which the adjective phrase (AP) qualifies the noun jono

(Notice that in the clause that corresponds to the above NP, jonos kludora toili (John is writing the book), jono has the ergative suffix and the 3 words can occur in any order : with the NP, jono does not take the ergative suffix and the 3 words must occur in the order shown.)

glói = to see

polo = Paul

timpa = to hit

jene = Jenny

glori polo timpala é = He saw paul hitting something

glori pà timpala ò = He saw me hitting her

glori hà (pás) timparwi ò = He saw that I had hit her

glori jene timpwala = He saw Jenny being hit

Now the question is where is this special NP used. Well it is used in situations where English would use a complement clause. For example with algo meaning "to think about",*

1) algara jono = I am thinking about John.

2) algara jono kludala toili = I am thinking about John writing a book.

Note ... According to Dixon, the standard English translation of 2) would be "I am thinking about John's writing a book" which I find quite strange even though English is my mother tongue. I have decided to call this sort of construction in béu a special kind of NP, while Dixon has called the equivalent expression in English the "-ing" type of complement clause. I think this is just a naming thing and doesn't really matter.

*"to think (that)" is alhu in béu. alhu also translates "to believe".

..

..... Punctuation and page layout

..

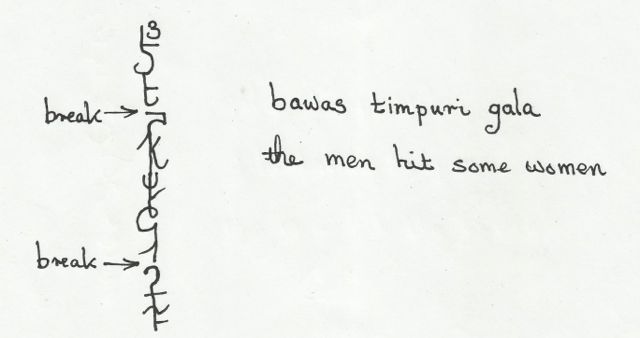

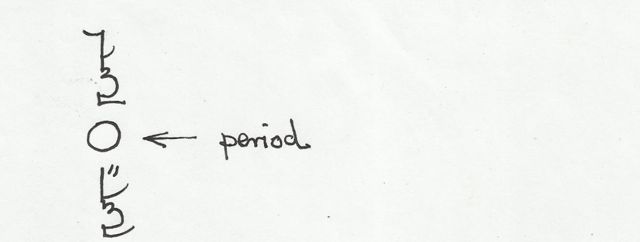

The letters in a word are always contiguous, that is there is always a line running right through the word. Writing is firstly from top to bottom and secondly from left to right.

Between words there is a small break in the line. See the figure below ...

..

..

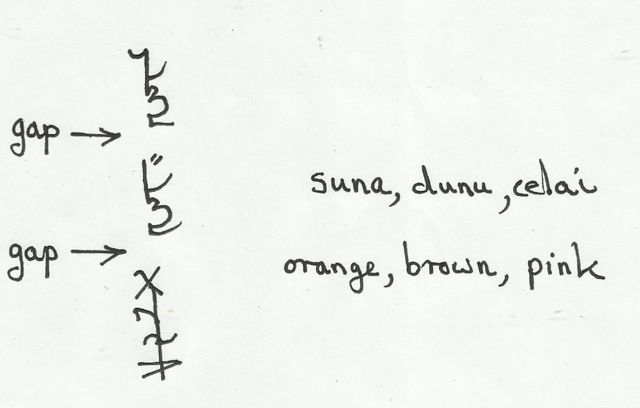

When you have items listed, béu is exactly the same as English : there is a pause between every item. A pause is represented by a gap in the writing system. See the figure below ...

..

..

By the way, the last two items on the list don't have a pause but are separated by wí "and".

..

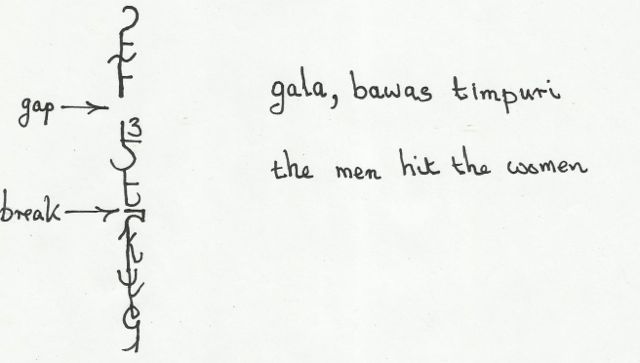

It is also a requirement of béu grammar that any NP's that are adjacent to each other, have a pause between them. Hence ...

..

..

The gaps in the writing system reflect exactly where pauses occur. So in a passage, where it would be appropriate for a speaker to take a breath, you will find a corresponding "gap".

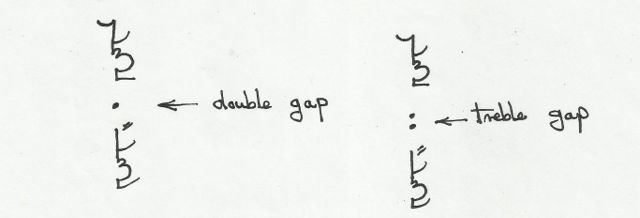

Single gaps are very common. Occasionally you can have "double gaps" and even "treble gaps". These rare creatures represent "pregnant pauses" which are sometimes used for comic effect.

..

..

There is also a punctuation mark called the "sunmark". This is basically a full-stop.

..

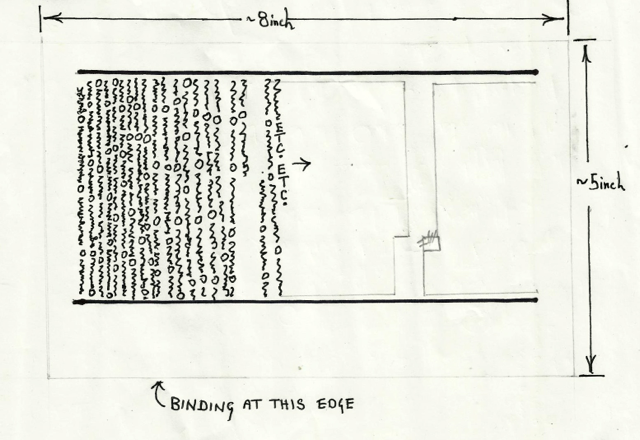

In a normal narrative, everything is written in "textblocks". See figure below ...

..

..

Textblocks fit in between "rails" about 4 inches apart. The width of a block should be between 60% and 90% * of the block height. Of course it is best to start a new block when the scene of the narrative changes or there is some discontinuity of the action, but this is not always possible.

There is no way to split a word between two lines (as we can do in the West by using two hyphens). If a line (or should I say column) ends in a "sunmark", the next column will begin with a sunmark.

The first text block starts at the top left (as you would expect). The second textblock starts below where the first text block stops. In fact the vertical space between the stop and the start of the two textblocks is equal to the horizontal "interblockspace" (see the figure above).

When you come to the end of the page (you will have some sort of margin of course and not go all the way to the edge), you simply continue the block on the LHS of the next rail (or page).

There are two sizes for books. For all hardback books the size is about 8 inches by about 11 inches. For all paperback books the size is about 5 inches by about 8 inches. They are stored as shown in the figure below.

..

..

Unlike books produced in the West, these books are held with the spine horizontal when being read. The hardback page has two "rails" per page (i.e. three dark lines).

On the paperback book, the title is written on the spine and on the front of the book. On the hardback book the title is written on the front, also there is a flap that slides into the spine. However when the book is stored on a shelf, it is pulled out and hangs down. Hence the hardback books can be easily located, even when they are in the bookshelf.

In every textblock, one word is highlighted. It is usually a noun and the more iconic the better (for example Elephant or Mouse are highly iconic). This word is highlighted in a red colour. Sometimes an active verb is highlighted. These are highlighted in a green colour. Sometimes an adjective is highlighted ... orange colour. Sometimes an infinitive is highlighted ... pink colour

A book will be divided into chapters. A chapter will have a number and usually a title as well. Either at the end of the book or just after the chapter, there will be a page, in which all the highlighted words for a chapter are listed in order. Instead of referencing things by page number, things are reference by chapter and textblock (indictated by the highlighted word(s) ).

Any particular word in a book can be reference by 5 parameters ...

1) "title of book"

2) "title of chapter" (or "number of chapter")

3) the textblocks position (i.e. textblock number 5) plus the highlighted word(s)

4) the number of the sunmark (the number zero is used if the word being referenced is before the first sunmark

5) the number of the word

Also when direct dialogue is quoted ... the words of the first protagonist is highlighted in yellow ... those of the second in blue ??

* Occasionally very narrow blocks can not be avoided. And of course in mathematical/scientific tracts the tracts are all over the place ... interspersed with diagrams and what have you.

..

..... Polar question and focus

..

A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a YES/NO answer), we stick the particle ʔái on the end of the sentence.

ʔái is neutral as to the response you are expecting.

To answer a positive question you answer ʔaiwa "yes" or aiya "no".

To answer a negative question positively you answer ʔaiwa.

To answer a negative question negatively, you must repeat back the entire clause (with the proper polarity of course).

For example ;-

Question 1) glà (sòr) hauʔe ʔái = Is the woman beautiful ? .......... If she is beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she isn't answer aiya.

Question 2) glà sorke hauʔe ʔái = Isn't the woman beautiful ? ........ If she isn't beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she is answer ò sòr hauʔe.

To bring a word into focus you put cù in front of it. For example ...

Statement ... báus glaye nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement ... báus cù glaye nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave the flowers. (English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to a word).

Any argument or in fact the verb itself can be focused in this way.

To question one element in a clause, you have cù in front of the element and ʔái sentence final.

Alternatively you can dispense with the cù and put the ʔái directly behind the element you want to question. For example ...

cù báus glaye nori alha ʔái = Is it the man that has given flowers to the woman ?

báus ʔái glaye nori alha = Is it the man that has given flowers to the woman ?

..

..... Content questions

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 7 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

A corresponding set of béu question words are given below.

..

| Question word | Noun/pronoun | Head for HRC ?? | |||

| nén nós | what | ||||

| mín mís món | who | ||||

| kói | when | kòi | occasion, time | koi.a | "the time that", when |

| déu | where | dèu | place | deu.a | the place that |

| kái | "what kind of" | kài | sort, type | kai.a | "the type that", "as" |

| láu | "how much" or "how many" | làu | amount | lau.a | the amount that |

| nái | which | ||||

| fáu | how |

..

*What about the ergative case ??

nenji = why, but as it is derived from nen in a regular way, it is not mentioned in the above table.

The head of headless relative clauses about things ... ʃì à or só ʃì à.

The head of headless relative clauses about people ... ò à or só ò à ... nù à or só nù à ... well actually any pronoun can be patterned like this.

In English as in about 1/3 of the languages of the world it is necessary to front the content question word.

In béu these words are usually also fronted. They must come before the verb anyway. If they come after the verb, they mean "somebody/something", "somewhere" etc. etc.

The pilana are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.

Here are some examples of content questions ...

Statement 1) báus glaye dori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Question 2) mís glaye dori alha = who gave flowers to the woman

Question 3) báus minye dori alha = to whom did the man gave flowers

Question 4) báus glaye nén dori = what did the man give to the woman

Question 5) báus yè glà nái dori alha = to which woman did the man give the flowers = báus dori ye glà nái alha

Statement 1) báus glaye dori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman .................known to speaker .......... known to addressee

Statement 2) báus dori yè glà alha = the man gave flowers to a woman .............................? ......................... unknown to addressee

Statement 3) báus dori yè é glà alha = the man gave flowers to some woman ..........unknown to speaker..... unknown to addressee

Statement 4) báus dori yè glà fana alha = the man gave flowers to a certain woman ... known to speaker ........ unknown to addressee

If NP before verb => known to addressee

If NP after verb => unknown to addressee

If NP has é (before the head) => unknown to speaker ... sort of

If NP has fana (after the head) => known to speaker ... fana = known ... fàu = to know

..

..... How A O and S arguments are identified

In this section we discuss pronouns and also introduce the S, A and O arguments.

béu is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings.

..

In English there is a fixed word order, which also helps to tell who did what to who when the participants are given as nouns instead of pronouns. In béu the order of the verb and the participants are not fixed as in English.

..

glàs baú timpori = The woman hit the man

glà baús timpori = The man hit the woman

It can be seen that "s" is added to the "doer" of the action.

..

However consider the clause below ...

..

glà doikor = The woman walks

It can be seen that the "doer" does not have an attached "s" in this case.

The reason is that "to walk" is an intransitive verb while "to hit" is a transitive verb

It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument.

It is the convention to call the "doer" in a transitive clause the A argument and the "done to" the O argument.

A language that has the S and O arguments marked in the same way is called an ergative language

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument).

In béu ò is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : ós is the "doer to"(A argument).

..

..... Transitivity and the useful word "á"

..

In béu a verb is either transitive or intransitive. There is no "ambitransitive verbs as in English.*

For example ... in English, you can say ... "I will drink water" or simply "I will drink"

The second option is not allowed in béu ... as "drink" is a transitive verb, you must say "I will drink something" = solbaru á

Well actually you can, the á can be dropped ... just as easily as the pás is dropped. The point is that the listener "knows" that there are always 2 arguments. The same can not be said in English when you here "he drinks" ... it could mean that the subject habitually drinks alcohol, in which case we have only one S argument.

For another example ... in English, you can say ... "the woman closed the door" or simple "the door closed".

The second option is not allowed in béu ... as "close" is a transitive verb, you must say "something closed the door" = pintu nagori ás

(Actually there is another option for expressing the above ... you can change any transitive verb to an intransitive verb ... pintu nagwori = "the door was closed"

..

If an argument is definite in béu it is usually comes before the verb, and if indefinite it usually comes after the verb.

Now the word é is by definition indefinite. It actually means "somebody" OR "something". What happens if this word is put before the verb.

Well something quite interesting happens ... é changes into a question word meaning "who" or "what"

For example ... és pintu nagori = Who/what closed the door

For another example ... "what will I drink" = é solbaru

And yet another one ... "who drank the water" = és moze solbori

..

*Actually you can tell the transitivity of a verb (for a word of more than one syllable) by looking at its last consonant. If the last consonant is j b g d c s k or t then it is transitive. If it is ʔ m y l p w n or h it is intransitive.

There is about 300 words that have an intransitive form as well as a transitive form, only differing in their final consonant. The relationship between these final consonants is shown below. x means "any vowel".

| transitive | intransitive |

| -jx | -lx |

| -bx | -ʔx |

| -gx | -mx |

| -dx | -yx |

| -cx | -wx |

| -sx | -nx |

| -kx | -hx |

| -tx | -lx |

..

NB ... y and w are usually not allowed to be the second element in a word ... but in these special words, they are.

..

..... Correlatives

..

| ibu | anybody, any one | ivanyo | anything |

| ebu | somebody, some one | evanyo | something |

| ebua | some people | evanyoi | somethings |

| ubu | everybody (collective) | uvanyo | everything (collective) |

| yubu | everybody (individual) | yuvanyo | everything (collective) |

| jubu | nobody, no one | juvanyo | nothing |

| .... | .... | .... | .... |

| iko | anytime | ide | anywhere |

| eko | once | ede | somewhere |

| ekoi | some times | edeu | some places |

| uko | always | ude | everywhere (collective) |

| yuko | everytime | yude | everywhere (collective) |

| juko | never | jude | nowhere |

| .... | .... | .... | .... |

(SideNote) ...

-bu does not occur as an independent word but does occur as a suffix ... beubu = a person who follows the precepts of béu

fanyo is an independent word, meaning "object", "physical thing"

-ko is not an independent word or a suffix. However kòi is a word meaning "occasion", "time".

-de is not an independent word. However dèuì is a word meaning "place".

(SideNote) ...

kói = when

déu = where

koi.a = the time that, when

deu.a = the place that, where

koigan = time

deugan = space

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences