Béu : Chapter 7: Difference between revisions

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

==Verb chains== | ==Verb chains== | ||

I have gone and met him => '''jari twé ò''' | |||

''' | I have gone (in order) to meet him => '''jari tweji ò''' | ||

- | He is lowering John down the cliff-face to the ledge => '''ós gora jono''' cliff '''gìa''' ledge'''ye''' ??? | ||

'''jompai gauho''' = to erode {s, ∅} ... this is a lexeme made up of two non-adjacent words. In a lexeme made with the -'''ho''' element, the word order is always important. | '''jompai gauho''' = to erode {s, ∅} ... this is a lexeme made up of two non-adjacent words. In a lexeme made with the -'''ho''' element, the word order is always important. | ||

| Line 229: | Line 193: | ||

DO WE ALWAYS GET COMPOUND GOMIA FORMS ?? | DO WE ALWAYS GET COMPOUND GOMIA FORMS ?? | ||

You would say "The rain erodes the mountain-range" rather than "The rain rubs the mountain-range down" because the "real" meaning of "rub" involves something solid against a something rigid. ?? | You would say "The rain erodes the mountain-range" rather than "The rain rubs the mountain-range down" because the "real" meaning of "rub" involves something solid against a something rigid. ?? | ||

WHEN WE INTRODUCE "ALONG" (FOR EXAMPLE) WE ARE INTRODUCING A NEW OBJECT IN THE CLAUSE ??? | WHEN WE INTRODUCE "ALONG" (FOR EXAMPLE) WE ARE INTRODUCING A NEW OBJECT IN THE CLAUSE ??? | ||

The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in '''béu''' anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)". | The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in '''béu''' anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)". | ||

I whistled while I walked = '''wizari doikan''' or you could say '''wizari saun doikala''' or because '''doikala''' is an adjective, if placed directly after a verb, it acts like an adverb => '''wizari doikala''' | I whistled while I walked = '''wizari doikan''' or you could say '''wizari saun doikala''' or because '''doikala''' is an adjective, if placed directly after a verb, it acts like an adverb => '''wizari doikala''' | ||

| Line 253: | Line 204: | ||

I saw John whistling = '''klari jono wiʒila''' | I saw John whistling = '''klari jono wiʒila''' | ||

----------------------------- | ----------------------------- | ||

Revision as of 13:32, 1 January 2015

..... kolape

This is a complement clause construction. In English there are 7 types of complement clauses, in béu there are only 3.

A complement clause is call a kolape in béu. The three types are briefly summarised below and then each of the types is discussed in more detail.

1) I remembered writing the book ... this conveys that the whole process of locking the door is going thru the speakers mind ... ???ari pá kludau toili

The béu form above looks similar to the English "I remembered to write the book". However this is NOT the meaning.

To say "I remembered to write the book" in béu you would say ???ari tá toili (rà) kludu ... see the section about participles.

2) I thought that I wrote the book ... takes the same form in béu ... olgari tá kludari toili

3) He asked me whether I had written the book ??? ... askori (pavi) tavoi kludari toili

kolape jù

In béu the word order is usually free. This is not true in a kalope jù

jonoS rì kéu = John was bad

(pà solbe moze pona sacowe)S rì kéu = my drinking the cold water quickly was bad

Notice that pà solbe moze pona sacowe behaves as one element. It has the same function as "John" in the previous example.

The word order inside kolape jù is fixed. It must be S V or A V O for a transitive clause (any other peripheral arguments are stuck on at the end).

Also notice that the ergative marker -s which is usually attached to the A argument is dropped. Actually for pronouns it is not just the dropping of the -s, but a change of tone also, so this form is identical to the O form of the pronoun.

The kolape above, if expressed as a main clause would be.

(pás) solbari saco* moze pona = I drank the cold water quickly

Other examples ;-

wàr solbe (I want to drink) is another example. (wò = to want)

klori jono timpa jene (he saw John hitting Jane) ... (klói = to see)

kolape jù? can be considered as a noun phrase and the fixed ordering of elements can be seen as a reflextion of the strict order of elements in a normal noun phrase

Subject1 Head2 Object3(Peripheral arguments4 x n)

1) The "A" argument or the "S" argument.

2) The verb.

3) The "O" argument, which would of course be non-existent in an intransitive clause.

4) Adverbs and everything else.

A gomia such as solbe can be regarded as a proper noun** and can be the head of a cwidauza (see a previous section)

or it can be the head of a kalope jù. But these two constructions are always distinct. For example you couldn't append a determiner to a kalope jù ... (or could you ??)

* in a main clause the adverb can appear anywhere if suffixed with -we. But in kalope jù the adverb must come after the Subject, Verb and Object.

** A gomia never forms a plural or takes personal infixes in the way a normal noun does. Also it only takes a very reduced subset of pilana, so a gomia can be regarded as an entity half way between nounhood and verb hood. For that reason I consider gomia as a part of speech, standing alongside "noun" and "verb".

kolape tá

In this form the full verb* is used, not the gomia. Also we have a special complementiser particle tá which comes at the head of the complement clause.

wàr tá jonos timporu jene = I want John to hit Jane

klori tá jonos timpori jene (he saw that John hit Jane) ... (klói = to see)

*Well not quite the full form. Evidentials are never expressed.

kolape tói

This is equivalent to English word "whether".

sa RAF kalme Luftwaffe kyori Hitler olga tena => The RAF's destruction of the Luftwaffe, made Hitler think again. ... here a gomiaza acts as the A-argument.

*in the combinations where sacowe immediately followed solbe it is merely saco

Things to think about

what is a gomiaza

Can this be used for a causative construction ??

..... Some linguistic terms in béu

By the way, while we are at it (defining linguistic terms)

nandau = word

semo = a clause ... from the verb "to say" sema

semoza = a sentence

jaudauza = a verb phrase or verb complex (commonly called a "predicate" by linguists). This is the verb together with the five modals.

feŋgi = a particle ... given above

plofa = a participle (P) ... there are 3 participles in béu

ʔasemo = a relative clause

kalope = a complement clause. There are three types of these ... kalope jù, kalope tà and kalope tavoi

A kalope jù is a gomiaza if it is more than one word long, if only one word long it is simply a gomia

A gomiaza can comprise of subject ... gomia ... object ... adverb ... other peripheral terms

The term gomuaza is not used. You would use the word semo meaning clause.

taifi (that which is to be tied ??? check participles) = copular subject

taifo = copular complement

taifau = to tie

taifana = a copula

..... The parts of speech of béu

"Parts of speech" is linguistic jargon, which is referring to the different "classes" of words a language might have. For example "nouns", "verbs", etc. etc.

In fact nouns (N), verbs (V) and adjectives (A) are the big three, and after some debate over the last 30 years, it has been agreed that every language has these three word classes.

In béu a noun is called cwidau (cwì meaning a physical object), a verb is called jaudau (jàu meaning "to move"), and an adjective is called saidau (sái meaning "a colour").

There are other classes of words in béu as there are in other languages. béu has adverbs (wedau) but these don't really come into their own, being more a form an adjective takes in certain situations. Also a lot of words that are called adverbs in English are called particles (feŋgia) (F) in béu. Particles are a type of hold-all category for a word that doesn't fit into any of the other classes. Under the term "particle" many subclasses can be defined, and in fact some subclasses have a class membership of one. If you come across a word that can not easily be equated with any of the major word classes ... well then you probably have a feŋgi.

It is necessary to talk about another part of speech which i will refer to by the béu term gomia* (G). It is a form of the verb which is called the "infinitive" in the Western linguistic tradition.

* goma means "tail" and gomia means "tail-less". The reason for this is that a verb in a sentence functioning as verbs commonly do, has person, number, tense, aspect and evidentiality expressed on the verb as series of suffixes, hence the "tail". These items are not expressed on the gomia.

In contradistinction to gomia we have gomua (jaudau gomua to give the concept its full title) which is a verb in a sentence functioning as verbs typically do.

For example solbarin (I drank, so they say) is a gomua.

solbarin is built up from the gomia "solbe" ... first you delete the final vowel => then you add "a" meaning first person singular subject => then you add "r" meaning that the mood is indicative (as opposed to imperative or subjunctive) => then you add "i" meaning simple past tense => and finally you add "n" which is an evidential, meaning that the utterance is based on what other people have said.

solbarin is gomua pomo or "a full tail verb".

The three evidential markers are all optional, so they can quite easily be dropped. solbari (I drank) is what is called gomua yàu or "a long tail verb".

solbis (you lot drink) and solbon (let him drink) are gomua wái or "a short tail verbs" ... the first is an example of the imperative and the second is an example of the subjunctive (more linguistic jargon ... sorry).

solbai is called an part verb ???

== ..... Another relativizer

There is another relativized in béu that refers back to a whole proposition. In English "which" is sometimes given this function. For example ...

1) ... John had completely forgotten his wedding anniversary which really annoyed his wife.

béu uses nài in a similar way to how which is used in the above example. Also the same shorthand form is used for nài and nái. However no misunderstanding is possible since nài always has a pause before it (how do I do a comma ?) and nái always is immediately after a noun.

..... The conditional

iba = condition, stipulation

ibla = if .... occasionally the form ibala is used. When the longer form is used, it is showing that the speaker has a lot of doubt as to whether the eventuality will actually come to pass.

jú = then ... this is a conjunction, indicating that what follows follows on from what is before. That is, it shows that they are connected, part of the same train of thought or chain of actions.

The béu form for the conditional is .... ibla xxx xxx xxx jú xxx xxx xxx

Usually the tense of the verbs in the above two clauses is the future tense, but it does not have to be. Sometimes you can get quite complicated conditional linkages.

The irrealis form of the verb is also quite common in the conditional construction. For example ....

"If you had come to London, we would have met"

Verb chains

I have gone and met him => jari twé ò

I have gone (in order) to meet him => jari tweji ò

He is lowering John down the cliff-face to the ledge => ós gora jono cliff gìa ledgeye ???

jompai gauho = to erode {s, ∅} ... this is a lexeme made up of two non-adjacent words. In a lexeme made with the -ho element, the word order is always important.

In this case the case frame of the compound word follows the case frame of the original word.

WORK OUT CASE FRAMES FOR OTHER COMPOUNDS.

Also we have a compound gomia form, gaujompai meaning erosion.

DO WE ALWAYS GET COMPOUND GOMIA FORMS ??

You would say "The rain erodes the mountain-range" rather than "The rain rubs the mountain-range down" because the "real" meaning of "rub" involves something solid against a something rigid. ??

WHEN WE INTRODUCE "ALONG" (FOR EXAMPLE) WE ARE INTRODUCING A NEW OBJECT IN THE CLAUSE ??? The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in béu anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)".

I whistled while I walked = wizari doikan or you could say wizari saun doikala or because doikala is an adjective, if placed directly after a verb, it acts like an adverb => wizari doikala

to whistle = wiʒia

I saw John whistling = klari jono wiʒila

The causative construction

(pàs) dari jono dono = I made john walk

(pàs) dari jono timpa jene = I made John hit Jane ... in this sort of construction, jono, timpa and jene must be contiguous and jono should be to the left of jene.

To give and to receive

kyé = "to give" or "to allow" or "to let".

bwò = "to receive" or "to get" or "to undergo"

A central meaning of these two words are demonstrated in the two examples below.

1) jonosA kyori toiliO jenek = John gave a book to Jane"

Note that (as with all béu main clauses) the arguments can be in any order.

2) jeneA bwori toiliO (jonofi) = Jane got a book (from John)

O.K. the above is the usage normal usage of kyé and bwò. They sort of describe the same action but from two different perspectives.

Actually the words kyé, klamoi "show"a nd tamau "tell" share the following characteristic ... as well as their arguments appearing as in 1) ... there is an alternative arrangement allowed ...

3) jonosA kyori jeneO toilige = "John gave Jane with a book" or "John gave Jane using a book"

When a destination comes immediately after the verb ái "to go" the pilana -k is always dropped.

In a similar manner when a origin comes immediately after the verb kàu "to come" the pilana -fi is never dropped.

But as well as with their central roll, these two words have other uses as well.

The reciprocal construction

The reciprocal particle can be said to historically come from both kyé and bwò.

jono jene timpuri kyebwo = "John and Jane hit each other" = "John and Jane hit one and other"

kyebwo the reciprocal particle (usually comes immediately after the verb) is obviously derived from the phrase kyé bwò

Notice that normally we would have -s on both John and Jane ... however not in the reciprocal construction.

Also note that é(and) is not used between proper names.

To allow or let

kyé is used to express "to allow" or "to let".

John let Jane go => jonos kyori bái jenek

Note that this construction mirrors the construction in 1) above, with an infinitive substituted for indirect object (i.e. bé "to go" for toili "book").

The passive construction

bwò is involved in the passive construction.

3) jonosA timpori jeneO = John hit Jane

4) jeneS bwori timpa (jonotu) = Jane was hit (by John)

4) is the passive equivalent of 3) ... used when the A argument is unknown or unimportant.

If the agent is mentioned, he or she is marked by the instrumentive pilana.

Notice that all the derived verbs are transitive. There are three ways that we can make an intransitive clause.

1) pintu tí mapori = The door closed itself ... this form strongly implies that there was no human agent. Possibly the wind closed the door (or a supernatural element when it comes to that).

2) pintu bwori mapau = The door was closed ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

3) pintu lí mapa = The door became closed ... this uses the adjective form of mapa and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

By the way, the G-form of nava "open" is navai

Let us go back to gèu and consider gèu in an intransitive clause. As above we have 3 ways.

1) báu tí geusori = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved.

2) báu bwori gèus = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

3) báu lí gèu = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of gèu and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

Notice that naikes means the same as kyé sau naike (to give to be sharp) ... but why say this mouthful when you can simply say naikes.

Any single syllable adjective, must have the suffix du in all its verbal forms. For example ;-

àus = to blacken, maŋkeu = faces

ausuri maŋkiteu = they blackened their faces ... interesting construction ... we use the transitive form even tho' they perform the action on themselves.

The causative construction

du = "to do" or "to make"

(pàs) dari oye timpa glá = I made him/her hit the woman

(pàs) dari oye dono = I made him/her walk

Alternatively we can use the tá particle and drop the -ye

(pàs) dari tá (ó) donor = I made him/her walk

Is the below OK ?

bwari kyé bé = I received permission to go = I received to give to go.

jene bwori du dono = Jane was made to walk

Note that there are three verbs in a row in the line above. dono seems to qualify du, and du dono seems to qualify bwori

(pàs) bwari du solbe moze (jonotu) = I was made to drink the water (by John)

moze bwori solbe (jenetu) = The water was drunk (by Jane)

Who/what is responsible

1) pintu lí mapa = the door became closed ... this uses the adjective form of mapa and the "copula of becoming" láu.

Agent => Anything ... It could be that the agent was the wind ... or even some evil spirits ... use your imagination.

2) pintu bwori mapau = the door was closed ... this is the standard passive form. (By the way ... I don't mean pintu rì mapa when I say "the door was closed")

Agent => Human and the action deliberate ... It strongly implies that the agent was human but is either unknown or unimportant.

Now lets consider gèudu = "to turn green" ... ambitransitive, S and A ... as in English.

1) báu lí gèu = The man became green ... this uses the adjective form of gèu and the "copula of becoming" láu. This form has no implication as to the humanness of the agent.

Agent => Anything and the action could be accidental.

2) báu bwori geudu = The man was made green ... this is the standard passive form. It strongly implies a human agent but the agent is either unknown or unimportant.

Agent => Human and the action deliberate

3) báus tí geudori = The man made himself green ... this form implies that there was some effort involved and definitely a deliberate action.

Agent => The man and the action deliberate

Ambitransitive verbs

fompe is an intransitive and a transitive verb (S and A)

jene fompori = Jane tripped

jonos fompori jene = John tripped Jane

halka is an intransitive and a transitive verb (S and O)

pintu halkori = the door broke

jonos pintu halkori = John broke the door

A list of 6 ambitransitive (S and A) verbs

tonza = to awaken, to wake up

henda = to put on clothes

laudo = to wash

poi = "to enter" or "to put in"

gau = "to rise" or "to raise"

sai = "to descend" or "to lower"

To recognize as a transitive clause you must look for the ergative -s, if no -s then we have an intransitive clause.

Or alternatively you must look for the particle kyebwo

Tom Jerry halkuri = Tom and Jerry broke

Tom Jerry halkuri kyebwo = Tom and Jerry broke one and other.

..... The Calendar

The béu calendar is interesting. Definitely interesting. A 73 day period is called a dói. 5 x 73 => 365.

The phases of the moon are totally ignored in the béu system of keeping count of the time.

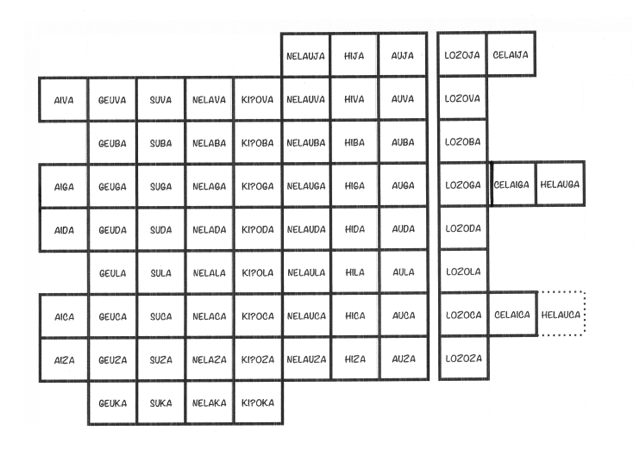

The first day of the dói is nelauja followed by hija, then auja lozoja celaija and then aiva etc. etc. all the way upto kiʔoka.

The days to the right are workdays (saipito) while the days to the left are days off work (saifuje). Each month has a special festival (hinta) associated with it. These festivals are held in the three day period comprising lozoga, celaiga, helauga. The five "months" are named after the 5 planets that are visible to the naked eye. The 5 big festivals that occur every year are also named after these planets.

| mercury | ʔoli | Month 1 | doiʔoli | Xmas... on 21,22,23 Dec | hinʔoli |

| venus | pwè | Month 2 | doipwe | festival on 4,5,6 Mar | himpwe |

| mars | gú | Month 3 | doigu | festival on 16,17,18 May | hiŋgu |

| jupiter | gamazu | Month 4 | doigamazu | festival on 28,29,30 July | hiŋgamazu |

| saturn | yika | Month 5 | doiyika | festival on 9,10,11 Oct | hinyika |

hinʔoli ... This is the most important festival of the year. It celebrates the starting of a fresh year. It celebrates the stop of the sun getting weaker. It is centred on the family and friends that you are living amongst. Even though eating and drinking are involved in all the five festivals, this festival has the most looked-forward-to feasts.

himpwe ... People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various music and poetry competitions. Sky lanterns are usually released on the last day of this festival. On the first two days of the festival, what is called the "fire walk" is performed. This is to promote social solidarity. Each locality comprising up to 400 people build a fire in some open ground. These people are divided into 2 sections. One section to walk and one section to receive walkers. The walkers are further divided into groups. Each group is assigned another fire to visit and they set of in single file. Each of them carries a torch (a brand) ignited from the home fire. Upon arriving at the fire that they have been assigned (involving a walk of, maybe, 5 or 6 miles) they throw their brand into the fire as their hosts sing the "fire song". After that the visitors are offered much drinks and snacks by their hosts. There is considerable competition between the various localities to be the most generous host. The routes that people must go have been chosen previously by a central committee, but the destination is only revealed to the walkers just before they set out. On the second day the same thing happens but the two sections, the walkers and the receivers of the walkers, swap over rolls.

hiŋgu ... It is usual to get together with old friends around this time and many parties are held. Friends that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken to meet up with old acquainances. Also there is a big exchange of letters at this time. The most important happenings of the last year are stated in these letters along with hopes and plans for the coming year.

hiŋgamazu ... This festival is all about outdoor competitions and sporting events. It is a little like a cross between the Olympics games and the highland games. People gather at various regional centres to compete and spectate in various team and individual competitions. However care is taken that no regional centre becomes too popular and people are discouraged from competing at centres other than their local one. Also at this festival, a "fire walk" is done, just the same as at the "himpwe" festival.

hinyika ... Family that live some distance away are given special consideration. Often journeys are undertaken for family visits and ancestors ashboxes are visited if convenient. This is the second most important festival of the year. People often take extra time off work to travel, or to entertain guests. Fireworks are let of for a 2 hour period on the night of helauga. This is one of the few occasions where fireworks are allowed.

By the way, when a year changes, it doesn't change between months, it changes between lozoga and celaiga.

Every 4 years an extra day is added to the year. The doiʔoli gets a helauca.

béu also has a 128 year cycle. This circle is called ombatoze. There is a animal associated with every year of the ombatoze.

These animals are ;-

| wolf | weasel/ermine/stoat/mink | bullfinch | badger |

| whale | opossum | albatross | beautiful armadillo |

| giant anteater | lynx | eagle | cricket/grasshopper/locust |

| reindeer | springbok | dove | gnu/wildebeest |

| spider | Steller's sea cow | seagull | gorilla |

| horse | scorpion | raven/crow | python |

| rhino | yak | Kookaburra | porcupine ? |

| butterfly | triceratops | penguin | koala |

| polar bear | manta-ray | hornbill | raccoon |

| crocodile/alligator | wolverine | pelican | zebra |

| bee | warthog | peacock | capybara |

| bat | bear | crane/stork/heron | hedgehog |

| frog | lama | woodpecker | gemsbok |

| musk ox | chameleon | hawk | cheetah |

| lion | frill-necked lizard | toucan | okapi |

| dolphin | aardvark | ostrich | T-rex |

| kangaroo | hyena | duck | driprotodon(wombat) |

| shark | cobra | kingfisher | gaur |

| dragonfly | mole | moa | chimpanzee |

| turtle/tortoise | N.A. bison | black skimmer | panda |

| jaguar | snail | cormorant/shag | Cape buffalo |

| rabbit | colossal squid | vulture | glyptodon/doedicurus |

| beetle | seal | falcon | pangolin |

| megatherium | woolly mammoth | flamingo | baboon |

| elk/moose | squirrel | blue bird of paradise | lobster |

| tiger | gecko | grouse | seahorse |

| jackal/fox | octopus | swan | lemur |

| elephant | swordfish | parrot | auroch |

| giraffe | ant | puffin | iguana |

| mouse | crab | swift | mongoose/meerkat |

| smilodon | giant beaver | owl | mantis |

| camel | goat | hummingbird | walrus |

Each of these animals above is a toze, which can be translated as "token", "icon" or "totem ". omba means a circle or cycle. So you can see where the name for the 128 year period comes from.

The very last helauca of every ombatoze is dropped.

ombatoze is sometimes translated as "life", "generation" or "century"

xxx means a 4 year period. It also means "calendar".

The start of time

Year 2000 had 365.242,192,65 days

Every year is shorter than the last by 0.000,000,061,4 days

By adding one day every 4 years we get a 365.25 day year

If we then drop one day every ombatoze we get a 365.242,187,5 day year (actually very close to the actual year length)

Before 2084, the actual year will be bigger than the calendar year – after 2084 the actual year will be smaller than the calendar year

For this reason midnight, 22 Dec 2083 is designated the fulcrum of the whole system. That day will be time zero.

At the moment we are in negative time.

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences