Béu : Stuff discarded 3: Difference between revisions

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== ..... A discussion of English participles== | |||

.. | |||

Now English has two participles, the "active participle" and the "passive participle". | |||

They appear as adjectives (of course, an adjective derived from a noun is the definition of "a participle"), however both forms also appear in verb phrases. If you are given a clause out of context it is sometimes impossible to tell if the participle is acting as an adjective or as part of a verb phrase. For example ... first the "active participle" ... | |||

1) The writing man | |||

2) The man is writing | |||

3) The man is writing a book | |||

In 1) "writing" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "writing" and the sentence makes perfect sense. | |||

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test. | |||

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The man is green a book" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "is writing" is a verb phrase (one that has given progressive meaning to the verb "write"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "is writing" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning). | |||

... now the "passive participle" ... | |||

1) The broken piano | |||

2) The piano is broken | |||

3) The piano was broken | |||

4) The piano was broken by the monkey | |||

In 1) and 2) "broken" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "broken" and the sentence makes perfect sense. | |||

As for 3) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test. | |||

For 4) ... No not an adjective "The piano was green by the monkey" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 4) is that "was broken" is a verb phrase (one that has given passive meaning to the ambitransitive verb "break"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 3). The proper analysis of this could be that "was broken" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 3) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations<sup>*</sup> when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning). | |||

<sup>*</sup>The five-week deadlock between striking Peugeot workers and their employer was broken yesterday when the management obtained a court order to end a 10-day sit-in at one of the two factories in eastern France, Sarah Lambert writes. | |||

I would say either analysis is valid for the above sentence. | |||

.. | |||

== ..... Copula's== | == ..... Copula's== | ||

Revision as of 22:54, 14 December 2014

..... A discussion of English participles

..

Now English has two participles, the "active participle" and the "passive participle".

They appear as adjectives (of course, an adjective derived from a noun is the definition of "a participle"), however both forms also appear in verb phrases. If you are given a clause out of context it is sometimes impossible to tell if the participle is acting as an adjective or as part of a verb phrase. For example ... first the "active participle" ...

1) The writing man

2) The man is writing

3) The man is writing a book

In 1) "writing" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "writing" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 2) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 3) ... No not an adjective "The man is green a book" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 3) is that "is writing" is a verb phrase (one that has given progressive meaning to the verb "write"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 2). The proper analysis of this could be that "is writing" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 2) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

... now the "passive participle" ...

1) The broken piano

2) The piano is broken

3) The piano was broken

4) The piano was broken by the monkey

In 1) and 2) "broken" is definitely an adjective. For instance you can substitute "green" for "broken" and the sentence makes perfect sense.

As for 3) ... well could be an adjective ... it passes the green-substitution-test.

For 4) ... No not an adjective "The piano was green by the monkey" doesn't make sense. The proper analysis of 4) is that "was broken" is a verb phrase (one that has given passive meaning to the ambitransitive verb "break"). Now after we have figured this out we should have another look at 3). The proper analysis of this could be that "was broken" is a verb phrase. In fact there is no way to be sure and we would have to see the context in which 3) is embedded (and even then, there would be certain situations* when either analysis could be valid. I would say that it is because of these situations in which either analysis is valid that let the original adjectival meaning spread and become a verbal meaning).

*The five-week deadlock between striking Peugeot workers and their employer was broken yesterday when the management obtained a court order to end a 10-day sit-in at one of the two factories in eastern France, Sarah Lambert writes.

I would say either analysis is valid for the above sentence.

..

..... Copula's

..

The word copula comes from the Latin word "copulare" meaning "to tie", so a copula is a verb that ties. In béu(as in other languages) they differ from normal verbs in that they are quite irregular.

Also in béu a copula clause taiviza requires a specific word order and the s (the ergative case) is never suffixed to any noun, as normally happens when a verb is associated with two nouns.

... jìa

jìa is the béu main copula and is the copula of state. It is the equivalent of "to be" in English, which has such forms as "be", "is", "was", "were" and "are".

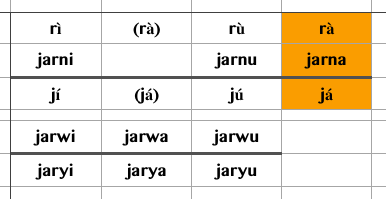

The table below echoes the second table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In three rows (the second and the two at the end) the copula includes the subject marker. In the table a representing first person singular is given. In rows 1 and 3 the copula does not include the subject marker (so obviously when these form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedent word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or já followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Actually rà is usually dropped completely.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... gí já moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... pá rà moltai = I am a doctor

Another situation where rà tends to be used is when either the subject or the copula complement are longish trains of words. For example ...

solboi alkyo ʔá dori rà sawoi = Those alcoholic drinks that she made are delicious.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

... làu

làu is the béu is the copula of change of state. It is the equivalent of "become" in English.

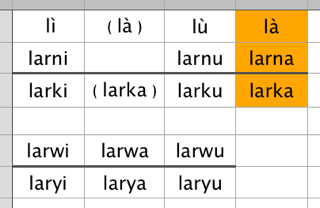

Again the table below echoes the table given in "The R-form of the verb"

In four rows (the second, third and the two at the end) the copula includes the cenʔo. In the table the a of the first person singular is given. In the first row the copula does not include the cenʔo (so obviously when this form are used the subject must be expressed as an indepedant word)

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have two entries enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a present tense copula or a negative present copula you would express it periphrastically ... you would use rà or ká followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

As you can see this copula is more regular than the main copula.

The evidentials are appended to the copula as they would be to a normal verb.

làu haube = to become beautiful OR to become a beautiful woman

... The copula of existence

Some languages have a verb to indicate that something exists. twái

This usually introduces a new protagonist in a narrative. The new protagonist is by definition, indefinite. For example ...

twor glá gáu ʔaiho = There was an old and ugly woman

Often it is used with a phrase of location.

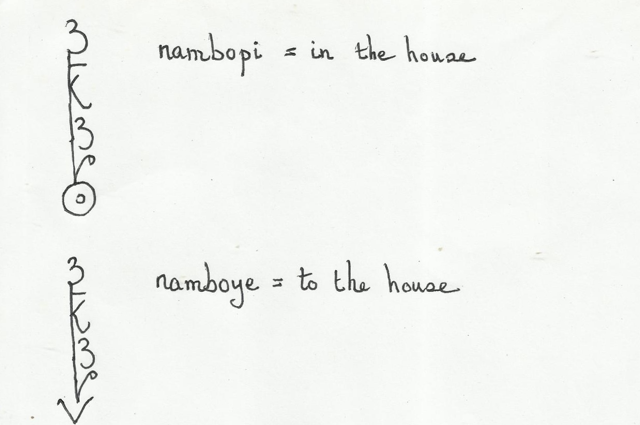

nambopi twuru aiba glabua = There will be three people in the house .... 3 people are in the house ???

There is no word that corresponds to "have". The usual way to say "I have a coat" ...

pán twor kaunu = "at me exists a coat"

olwa = to exist

elya = to not exist

??????????????????

há = place

dí = this

dè = that

While you sometimes come across the há dí the word hái is the usual way to express "here".

In a similar manner you sometimes come across the há dè the word ade* is the usual way to express "there".

*This word is an exception to the rule that inside a word and between vowels, d can be either pronounced as "d" or "ð". In ade the d is always pronounced "ð".

There is a house = A house exists = ade (rà) nambo

This is patterned on the more general locative construction.

In the apple tree is a beehive ????

ade pona paye = "I feel cold" ... maybe against expectations ... no reason to think that other people would be cold.

ʃi pona = "It is cold" ... everybody should feel cold

..

... 8 co-ordinates

There are 6 suffixes, that when attached to a noun, make an adjective.

nambo = house

nambokoi = above the house

nambobeu = below the house

nambofia = this side of the house ... béu speakers, if a building is in side, prefer to specify a position w.r.t. their own position, and not to what is called "front" my convention.

nambopua = the far side of the house

namboʒi = to the left of the house

nambogu = to the right of the house

Also there are 2 suffixes, that when attached to an infinitive, make an adverb.

solbe = "to drink" or "drinking"

solbetai = before drinking

solbejau = after drinking

Now in an infinitive phrase the constituent order is Subject Object Infinitive, so ...

moze solbetai jonos CHECKED THE GLASS WAS CLEAN = Before drinking the water, John checked that the water glass was clean.

Also we have the constructions ...

moze solben jono KEPT AN EYE OUT FOR TIGERS = While drinking water, John kept an eye out for tigers.

jono moze solbewe I DRINK BEER = I drink beer like John drinks water

..

..... The pilana

..

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON are called "cases". The classical languages, Greek and Latin had 5 or 6 of these. Modern-day Finnish has about 15 (it depends on how you count them, 1 or 2 are slowly fading away). Present day English still has a relic of a once more extensive case system : most pronouns have two forms. For example ;- the third-person:singular:male pronoun is "he" if it represents "the doer", but "him" if it represents "the done to".

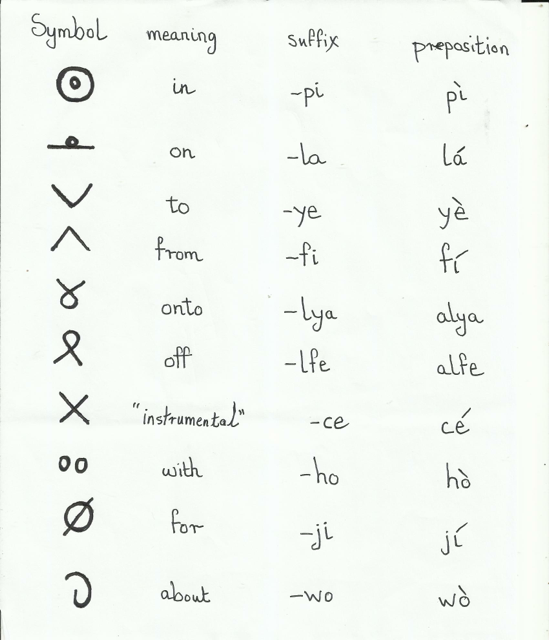

The 12 béu case markers are called pilana

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana <= (pila + ana), in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle". It is an adjective which means "putting (something) in position".

As béu adjectives freely convert to nouns*, it also means "that which puts (something) in position" or "the positioner".

Actually only a few of them live up to this name ... nevertheless the whole set of 12 are called pilana in the béu linguistic tradition.

..

..

The pilana are suffixed to nouns and specify the roll these nouns play within a clause.

As well as the 10 illustrated above, we have s for the ergative case and n for the locative case. Also we have the unmarked case which represents the S or O argument.

sá and nà are the free-standing variants of -s and -n.

The pilana specify the roll that a noun has within a clause. However both the ergative case and the locative case (and a few other cases) can specify what rolls a noun has within a NP.

For example nambo pàn = "a/the house at me" or "my house"

timpa báus glà = the man's hitting of the woman ... this is an example of an infinitive NP.

letter blicovi = the letter from the king

pen gila = a pen on your person

As shown above the pilana are represented by their own symbols. Or at least the ten that do not consist of single letters.

For the suffix form of the first 2 and last 2 symbols given above, the end of the word proper "touches" the symbol. For the other 6 symbols, the word proper "impinges" upon the symbol. See below ...

..

..... Rules governing the pilana

..

Now one quirk of béu (something that I haven't heard of happening in any natural language), is that the pilana is sometimes realised as an affix to the head of the NP, but sometimes as a preposition in front of the entire NP. This behaviour can be accounted for with thing with two rules.

1) The pilana attaches to the head and only to the head of the NP.

2) The NP is not allowed to be broken up by a pilana. The whole thing must be contiguous. So if a NP has elements after the head the case must be realised as a preposition and be placed in front of the entire noun phrase.

3) No two pilana can be stuck together (WOULD THIS EVER HAPPEN ??)

So if we have a NP with elements to the right of the head, then the pilana must become a preposition. The prepositional forms of the pilana are given on the above chart to the right. These free-standing particles are also written just using the symbols given on the above chart to the left. That is in writing they are shorn of their vowels as their affixed counter-parts are.

Here are some examples of the above rules ...

..

fanfa = horse

sonda = son

blico = king

fanfa sondan = the horse of the son

sonda blico = the son of the king

However the suffixed form can only be used if the genitive is a single word. Otherwise the particle na must be placed in front of the words that qualify. For example ;-

We can't say *fanfa sondan blicon however. The -n on sonda is splitting the NP sonda blico.

So we must say fanfa nà sonda blicon

Some more examples ...

fanfa nà sonda jini blicon = "the horse of the king's clever son

fanfa nà sonda nà blico somua = "the horse of the fat king's son"

Here are some more examples of the above rules ...

pintu nambo = the door of the house

pintu nà nambo tuju = the door of the big house

When one of the specifiers is involved we have two permissible arrangements.

1) pintu á nambon= the door of some house

2) pintu nà á nambo = the door of some house

1) is the more usual way to express "the door of some house", but 2) is also allowed as it doesn't break any of the rules.

This also goes for numbers as well as specifiers.

papa auva sondan = the father of two sons

papa nà auva sonda = the father of two sons

..

*Another case when the pilana must be expressed as a prepositions is when the noun ends in a constant. This happens very, very rarely but it is possible. For example toilwan is an adjective meaning "bookish". And in béu as adjectives can also act as nouns in certain positions, toilwan would also be a noun meaning "the bookworm". Another example is ʔokos which means "vowel".

The pilana and the relative clause

We have already seen that the final element of a NP can be a relative clause and we introduced the two particles à and às : corresponding to "who" and "whom".

Actually the basic relativizer is à and -s is the ergative case marker. The other case markers (well most of them) can also be suffixed to the à relativizer.

àn quite a common relativizer also.

Remember when we talked of the NP before we said a genitive (or a locative) can go as the last element in the adjective slot. For example ...

nambo jonon = John's house

However if the element that must become the genitive is longer than one word, the relativizer àn must be used. For example ...

nambo àn báu jutu = The big man's house.

WAIT ... HOW DOES THIS SQUARE UP WITH THERE BEING TWO FORMS OF THE "N" CASE .... SUFFIXING FORM AND FREE STANDING FORM ??

"the man ate the apple on the table" ... ambiguous in English

ALL THE BELOW SHOULD BE AFTER THE PILANA IS INTRODUCED

the basket api the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman aye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town avi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad à alya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.*<-sup>

the boat à alfe you have just jumped is unsound.*<-sup>

báu ás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

nambo àn she lives is the biggest in town.

Note ... The man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man that own dog that I shot, reported me to the police

báu aho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife age he severed the branch is a 100 years old

The old woman aji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy aco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

..

..... Definiteness

..

An interesting concept ... let us think about how English handles it.

..

The béu definite/indefinite

..

Well the person you are talking to is the person you want to impart the message to (the second person), so basically whether you use "a" or "the" will dependent on the addressee's knowledge of the relevant NP. For example ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | |

| I car want buy | 1 |

| I want buy car | 0 |

And to show that the speaker does not have a particular car in mind either he would say "I want buy some car"

but of course he would have some minimum requirements, if he had no minimum requirements he would say "I will buy any car"

..

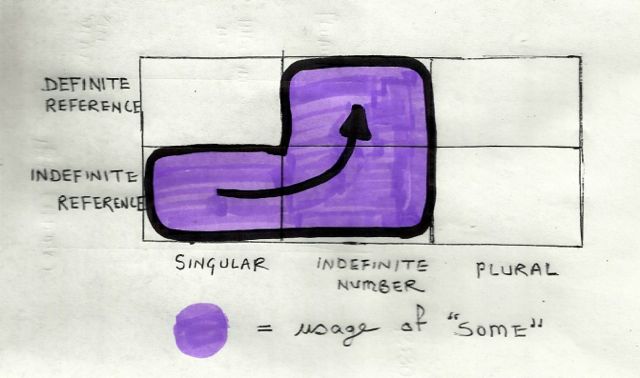

The use of é is very like the use of "some" in English ... a bit of doubt as to whether it makes the NP definite for the 1st person or for the 3rd person.

..

Usage of "this" and "that"

???

3) unknown to speaker but known to listener ... "that dog that bit you yesterday was put down" .... or equally valid ... "the dog that bit you yesterday was put down"

The question here is, of course, if the dog is "totally" unknown to the speaker ... why is here speaking about it ... ah, we must go deeper

Or consider this Norwegian, getting more definite in six easy steps.

5) She wants to marry a Norwegian ............. Could be any Norwegian. "She" does not even have any definite Norwegian in mind.

6) She wants to marry a Norwegian ............. Unknown to speaker and listener. But "she" has her eye on a particular Noggie.

7) She wants to marry some Norwegian ..... Not any Norwegian but the speaker known very little about him and the listener nothing.

8) She wants to marry a Norwegian** ........ Known to speaker but unknown to listener

9) She wants to marry this Norwegian ........ Known to speaker but unknown to listener

10) She wants to marry that Norwegian ....... Known to speaker and listener

9) and 10) can be said to be "half-definite" (my own term) The Norwegian is known but as a sort of peripheral character that hasn't as yet impinged on the consciousness* of the interlocutors that much. As/if he becomes more into focus in the interlocutors lives he will, of course, become, the Norwegian (or more probably Oddgeir or Roar or what have you).

The use of this and that for "half-definite" makes sense ... it is iconic. "This thing" is near the speaker hence seen, touched, smelt by the speaker ... known to the speaker.

"That thing" is out in the open, hence experienced/known to both speaker and listener.

*Or the world-model that we each build up inside our heads.

**Notice that "She wants to marry a Norwegian" is ambiguous ... it could either have the implications of either 5), 6) or 8).

But enough of English. béu makes a noun more definite by putting it further to the left. To have an obligatory a or the in front of every noun is wasteful. However non-obligatory particles (such as "some" are fine)

Basically if a noun or noun phrase is to the left of the verb* it is definite, if it is to the right it is indefinite. For example ;-

báus timpori glà = The man hit a woman

glà timpori báus = A man hit the woman

However this rule does not effect proper names and pronouns. They are always definite so they can wonder anywhere in the clause and it doesn't make any difference.

*When I say verb here I am not counting the three copula's. They always have the order

Copula-subject copula copula-complement

Also dependent clauses have fixed word order ???

..

Some original thought on "a" and "the"

..

Well the person you are talking to is the person you want to impart the message to (the second person), so basically whether you use "a" or "the" will dependent on the addressee's knowledge of the relevant NP. For example ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | |

| I bought the car | 1 |

| I bought a car | 0 |

..

In the above table I am using terminology from the subject of logic ... 1 = yes, 0 = no, X = yes or no

..

So this is the BASIC difference between definite and indefinite.

..

In the above example (because of the "situation") we can also say ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 1st person | ... when 1st person means the speaker of course | |

| I bought the car | 1 | |

| I bought a car | 1* |

..

* Logic makes this a "1" ... not the grammar

..

We can combine the two tables above ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | ... | Relevant NP known to 1st person | |

| I bought the car | 1 | 1 | |

| I bought a car | 0 | 1 |

..

Now lets change the "situation". We will change it as to its "reality" or 'realisation" ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | ... | Relevant NP known to 1st person | |

| I want to buy the car | 1 | 1 | |

| I want to buy a car | 0 | X *** |

..

But as we said at the start, the reason for saying something is to make the hearer understand, so the X given to the speaker is perfectly logical.

..

***The question will be asked "how to make unambiguous the speakers knowledge of the NP". Some ways are shown in the table below ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 1st person | ... when 1st person means the speaker of course | |

| I want to buy a certain car | 1 | |

| I want to buy this car ... | 1 | |

| There's a/this car (that) I want to buy. | 1 | |

| I want to buy a car, any car ... | 0 |

..

Now lets introduce a 3rd person.

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | Relevant NP known to 1st person | ||

| She married the American | 1 | 1 | |

| She married an American | 0 | X |

..

"She" of course being the 3rd person.

..

Now let's expand the above table a bit ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | Relevant NP known to 1st person | Relevant NP known to 3rd person | |||

| She married the American | 1 | 1 | 1 * | ||

| She married an American | 0 | X | 1 * | ||

| She married some American | 0 | 0 ** | 1 * |

..

* Logic makes this a "1" ... not the grammar

** Actually many connotations about the speakers attitude when "some" is used. When said "tensely" shows disapproval. When said "whistfully" shows speakers unhappyness with his lack of knowledge about the American. This is the marked case of the indefinite so I guess many many (or any ?) unusual point of view on the speakers part will be coded by "some".

..

Now lets change the "situation". We will change it as to its "reality" or 'realisation" ...

..

| Relevant NP known to 2nd person | Relevant NP known to 1st person | Relevant NP known to 3rd person | |||

| She wants to marry the American | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| She wants to marry an American | 0 | X | X | ||

| She wants to marry some American | 0 | 0 | 1 |

..

So to summarise(and simplify) the above data, I would say ...

1) "the" or "a" chosen depending on whether the addressee (2nd person) knows the NP talked about

2) "some" is chosen over "a" to show that the NP is identifiable (but not necessarily by the 1st or 2nd person)

3) ... "some" also has picked up various connotations with regards to the 1st persons view of the NP under discussion.

A bit about "this" and "that"

The original meaning for these two, was when some object is unknown to the addressee but the speaker wants to make it known to the addressee. Typically he points (or gestures) to the object as he introduces it. He will qualify the object with "this" if it is near, and with the word "that" if it is not near.

Now in English, people have started using "this" when something is not in sight. It is used to indicate that the object is known to the speaker but not known to the addressee.

Probably the commonness of the above has prompted people to start saying "this here" instead of "this" by itself.

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences