|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | | == ..... The R-form of the verb== |

| == ..... Punctuation and page layout== | |

| | |

| The letters in a word are always contiguous, that is there is always a line running right through the word. Writing is firstly from top to bottom and secondly from left to right.

| |

| | |

| Between words there is a discontinuity (you can not really call it a space). See the figure below ...

| |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:Words-together.png]]

| | Now we should introduce the active forms of the verb (also referred to as the R-form). '''béu''' has quite a comprehensive set of tense/aspect markers. The active form of the verb is built up from the infinitive form. There is only one infinitive in '''béu'''. |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| There is only one punctuation mark in '''béu'''. It is called the "sunmark". It is used where a where there is a time gap in the spoken words. This can be a requirement of the grammar. See figure below ...

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| [[Image:TW_195.png]]

| |

| ( '''suna''', '''dunu''', '''celai'''' ... or "orange, brown, pink" ... it is a requirement of '''béu''' grammar, that there is a pause between items on a list)

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| Or it can just be because the speaker must stop to breathe in a bit.

| |

| | |

| Very occasionally you see a symbol as show on the RHS of the above figure. This "double-sun-mark" is used for pregnant pauses (often used for comic effect).

| |

|

| |

|

| In a normal narrative, everything is written in "textblocks". See figure below ...

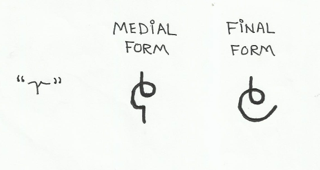

| | We will discuss the most-used form of the verb in this section, the R-form. But first we should introduce a new letter. |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:Blocktext.png]] | | [[Image:TW_191.png]] |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| Textblocks fit in between "rails" about 4 inches apart. The width of a block should be between 60% and 90% <sup>*</sup> of the block height. Of course it is best to start a new block when the scene of the narrative changes or there is some discontinuity of the action, but this is not always possible.

| | This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the R-form of the verb. |

|

| |

|

| There is no way to split a word between two lines (as we can do in the West by using two hyphens). If a line (or should I say column) ends in a "sunmark", the next column will begin with a sunmark.

| | So if you hear "r" or see the above symbol, you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause. (definition of a clause ('''semo''') = that which has one "r" ... ??? ) |

|

| |

|

| The first text block starts at the top left (as you would expect). The second textblock starts below where the first text block stops. In fact the vertical space between the stop and the start of the two textblocks is equal to the horizontal "interblockspace" (see the figure above).

| | O.K. ... the R-form is built up from the infinitive<sup>*</sup>. |

|

| |

|

| When you come to the end of the page (you will have some sort of margin of course and not go all the way to the edge), you simply continue the block on the LHS of the next rail (or page).

| | 1) First the final vowel is deleted. |

|

| |

|

| There are two sizes for books. For all hardback books the size is about 8 inches by about 11 inches. For all paperback books the size is about 5 inches by about 8 inches. They are stored as shown in the figure below.

| | <sup>*</sup>Excepts in rare cases (see "Adjectives and how they pervade other parts of speech") |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:Books.png]]

| | === ... Slot 1 === |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| Unlike books produced in the West, these books are held with the spine horizontal when being read. The hardback page has two "rails" per page (i.e. three dark lines).

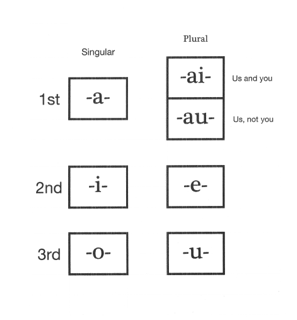

| | 2) one of the 7 vowels below is added. |

| | |

| On the paperback book, the title is written on the spine and on the front of the book. On the hardback book the title is written on the front, also there is a flap that slides into the spine. However when the book is stored on a shelf, it is pulled out and hangs down. Hence the hardback books can be easily located, even when they are in the bookshelf.

| |

| | |

| In every textblock, one word is highlighted. It is usually a noun and the more iconic the better (for example Elephant or Mouse are highly iconic). This word is highlighted in a red colour. Sometimes an active verb is highlighted. These are highlighted in a green colour. Sometimes an adjective is highlighted ... orange colour. Sometimes an infinitive is highlighted ... pink colour

| |

| | |

| A book will be divided into chapters. A chapter will have a number and usually a title as well. Either at the end of the book or just after the chapter, there will be a page, in which all the highlighted words for a chapter are listed in order. Instead of referencing things by page number, things are reference by chapter and textblock (indictated by the highlighted word(s) ).

| |

| | |

| Any particular word in a book can be reference by 5 parameters ...

| |

| | |

| 1) "title of book"

| |

| | |

| 2) "title of chapter" (or "number of chapter") | |

| | |

| 3) the textblocks position (i.e. textblock number 5) plus the highlighted word(s)

| |

| | |

| 4) the number of the sunmark (the number zero is used if the word being referenced is before the first sunmark

| |

| | |

| 5) the number of the word

| |

| | |

| | |

| Also when direct dialogue is quoted ... the words of the first protagonist is highlighted in yellow ... those of the second in blue ??

| |

| | |

| -----

| |

| | |

| <sup>*</sup> Occasionally very narrow blocks can not be avoided. And of course in mathematical/scientific tracts the tracts are all over the place ... interspersed with diagrams and what have you.

| |

| | |

| == ..... When a noun qualifies another one==

| |

| | |

| A) When the relationship between the nouns is one of ownership (usually a thing owned by a person), the thing comes first and it is followed by the person, with the person taking the '''pilana''' of location.

| |

| | |

| B) When the relationship between the nouns is "part to the whole", with the noun denoting the whole taking the '''pilana''' of location.

| |

|

| |

|

| C) When the relationship between the nouns is a kinship relationship the attribute noun takes the '''pilana''' of location.

| | [[Image:TW_109.png]] |

|

| |

|

| D) When the relationship between the nouns is of an attribute ( see page 265 ) the attribute noun takes the '''pilana''' of location.

| |

|

| |

|

| F) When the relationship between the nouns is association, the attribute noun takes the '''pilana''' of location.

| | LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the Western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she). In the béu linguistic tradition they are called '''cenʔo'''-markers. ('''cenʔo''' = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play) |

|

| |

|

| ------------ | | These markers represent the subject (the person that is performing the action). Whenever possible the pronoun that represents the subject is dropped, it is not needed because we have that information inside the verb with the '''cenʔo'''-markers. |

|

| |

|

| E) "above the house" = '''atas nambo''' ... for the same reason, people get their knickers in a twist about this one. However these "locative words" are a bit different as they are hardly ever used alone (maybe in the past they were, that is if '''béu''' had a past). If they are uttered without in isolation these days the invariably have '''ka''' suffixed.

| | Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one must be used when the people performing the action included the speaker, the spoken to and possibly others. The lower one must be used when the people performing the action include the speaker, NOT the person spoken to and one or more 3rd persons. |

|

| |

|

| M) "cup of water" = cup '''moze''' ... people get their knickers in a twist about this one. "cup" must be the head, but surely water is more important. That is, semantically "water" is the "head" but syntactically "cup" is the head.

| | Note that the '''ai''' form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE". |

| Well in the '''béu''' linguistic tradition we get around this by ???

| |

|

| |

|

| Z) There is one more case to talk about. If something is made out something, then we use the preposition '''mò''' meaning "out of". For example ....

| | LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun". |

|

| |

|

| a cup of gold ???

| | So we have 7 different forms for person and number. |

| | |

| Think about other situations in which we can use this partative case (look at Finnish).

| |

| | |

| == ..... How to bring a word into focus ==

| |

| | |

| Actually there is a way to focused elements in a statement which mirrors the way to focus elements in a question. We use '''cà''' for this.

| |

| | |

| Statement 1) '''báus glaye timpi alhai''' = the man gave flowers to the woman

| |

| | |

| Focused statement 2) '''báus glaye cà timpi alhai''' = It is the woman to whom the man gave the flowers.

| |

| | |

| Any argument or in fact the verb itself can be focused in this way.

| |

| | |

| == ..... How to ask a polar question ==

| |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

| | === ... Slot 2 === |

| | |

| To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a YES/NO answer), we stick the particle '''ʔái''' on the end of the sentence.

| |

| | |

| '''ʔái''' is neutral as to the response you are expecting.

| |

| | |

| To answer a positive question, YES or NO ( '''ʔaiwa àu aiya''' ) is sufficient.

| |

| | |

| To answer a negative question positively, YES ( '''ʔaiwa''' ) is enough.

| |

| | |

| To answer a negative question negatively, you must give an entire clause.

| |

| | |

| For example ;-

| |

| | |

| Question 1) '''glà (rà) haube ʔái''' = Is the woman beautiful ? .......... If she is beautiful, answer '''ʔaiwa''', if she isn't answer '''aiya'''.

| |

| | |

| Question 2) '''glà ká haube ʔái''' = Isn't the woman beautiful ? ........ If she isn't beautiful, answer '''ʔaiwa''', if she is answer '''ò rà hauʔe'''. (notice that the copula must be used in this case)

| |

| | |

| The above method questions the entire clause. However if you want to question one element in a clause, then you front that element and have '''ʔái''' immediately after.

| |

| | |

| Statement 1) '''báus glaye kyori alhai ''' = the man gave flowers to the woman

| |

| | |

| Straight question 2) '''báus glaye kyori alha ʔái''' = did the man gave flowers to the woman ?

| |

| | |

| Focused question 3) '''glaye ʔái báus kyori alha''' = Is it the woman that the man gave flowers to ?

| |

| | |

| Focused question 4) '''báus ʔái glaye kyori alha''' = Is it the man that gave flowers to the woman ?

| |

| | |

| Focused question 5) '''alha ʔái báus glaye kyori''' = Is it flowers that the man gave to the woman ?

| |

| | |

| Focused question 6) '''kyori ʔái báus glaye alha''' = the man GAVE flowers to the woman ? (a possible situation ... the speaker has previously thought the woman had stolen the flowers)

| |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| == ..... How to ask a content question ==

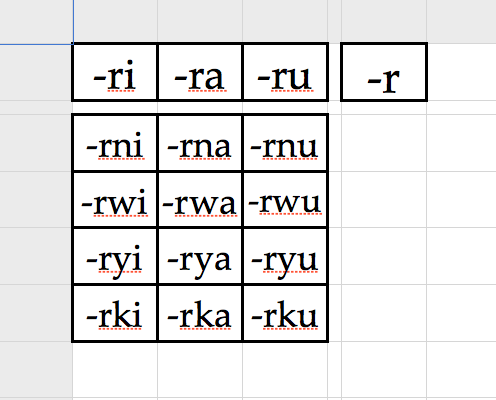

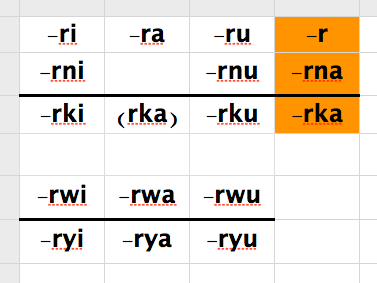

| | 3) now one of the 16 markers shown below is added. 16 is quite a respectable number, as far as tense/aspect markers go.<sup>*</sup> |

|

| |

|

| ..

| |

|

| |

|

| English is quite typical of languages in general and has 7 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

| | [[Image:TW_116.png]] |

|

| |

|

| A corresponding set of '''béu''' question words are given below.

| |

|

| |

|

| ..

| | Now these markers represent what are called tense/aspect markers in the Western linguistic tradition. In the '''béu''' linguistic tradition, they are called '''gwomai''' or "modifications". ('''gwoma''' = to alter, to modify, to adjust, to change one attribute of something). |

| | |

| {| border=1

| |

| |align=center| what/who

| |

| |align=center| '''é'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| where

| |

| |align=center| '''én'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| when

| |

| |align=center| '''eku'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| how

| |

| |align=center| '''ewe'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| what type of

| |

| |align=center| '''emo'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| why

| |

| |align=center| '''ega'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| how much

| |

| |align=center| '''eli'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| how many

| |

| |align=center| '''eno'''

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| '''é''' is the word most commonly used and it is usually plain from context whether a human or non-human argument is being considered. However there are two more words that are occasionally used. These are '''ebu''' "who" and '''eʃi''' "what".

| |

| | |

| In English as in about 1/3 of the languages of the world it is necessary to front the content question word. | |

| | |

| In '''béu''' these words are usually also fronted. They must come before the verb anyway. If they come after the verb, they mean "somebody/something", "somewhere" etc. etc.

| |

| | |

| The '''pilana''' are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.

| |

| | |

| Here are some examples of content questions ...

| |

| | |

| Statement 1) '''báus glaye kyori alhai''' = the man gave flowers to the woman

| |

| | |

| Question 2) '''és glaye kyori alhai''' = who gave flowers to the woman

| |

| | |

| Question 3) '''báus eye kyori alhai''' = to whom did the man gave flowers

| |

| | |

| Question 4) '''báus glaye é kyori''' = what did the man give to the woman

| |

|

| |

|

| The above question words (apart from '''é''' itself) can be considered just examples of the common process of prefixing '''e''' to a noun, to give the meaning "which x" or "some x". | | The table above has the '''gwoma''' arranged according to form. The two arrays below have the '''gwoma''' arranged according to meaning. The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have one entry enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a negative present tense negative you would express it periphrastically ... you would use the tenseless negative '''-rka''' followed by the '''béu''' equivalent of "now" or "at the moment". |

|

| |

|

| '''kyù''' = occasion, time

| |

|

| |

|

| '''myò''' = kind, type

| | [[Image:TW_117.png]] |

|

| |

|

| '''gà''' = because

| |

|

| |

|

| '''lí''' = amount

| |

|

| |

|

| '''nò''' = number

| |

|

| |

|

| 5) '''báus é glaye kyori alhai''' = to which woman did the man give the flowers

| |

|

| |

|

| 6) '''báus kyori é glaye alhai''' = the man gave flowers to some woman

| |

|

| |

|

| 7) '''báus kyori glaye alhai''' = the man gave flowers to a woman

| | Looking at the upper table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... '''i''' for the past, '''a''' for the present and '''u''' for the future. |

|

| |

|

| Of course an interesting question is "in what way does 6) differ from 7).

| | '''-ri''' ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense. |

|

| |

|

| .. | | '''-ra''' ... Should only be used if the action is happening NOW. English uses "to be xxxing". For example '''doikara''' = I am walking ... ('''doika''' = to walk) |

|

| |

|

| | '''-ru''' ... This is the future tense. |

|

| |

|

| == ..... How A O and S arguments are identified==

| | '''-r''' ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly". |

|

| |

|

| In this section we discuss pronouns and also introduce the S, A and O arguments.

| | The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school), Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). Actually in '''béu''' the pattern is broken a bit, in that '''-rna''' has NOTHING to do with the activity going on at the time of speech, it is actually a tenseless habitual. Also '''béu''' and English behave the same in the following way ... whereas by logic we should use '''doikarna''' in "I walk (to school everyday)", in fact '''doikar''' is used. '''doikarna''' would be used only if we were going on to MENTION some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift) |

|

| |

|

| '''béu''' is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings. | | '''doikarna''' = "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use '''doikar''' |

|

| |

|

| .. | | '''-rnu''' ... Now English doesn't have a future habitual. But if it did it would have a roll. For instance, suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In '''béu''' you would answer '''doikarnu'''. |

|

| |

|

| In English there is a fixed word order, which also helps to tell who did what to who when the participants are given as nouns instead of pronouns. In '''béu''' the order of the verb and the participants are not fixed as in English.

| | The next row expresses the perfect tense. |

|

| |

|

| .. | | While the perfect tense, logically this doesn't have that much difference from the past tense it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John. And think about the difference in meaning between "she has fallen in love" and "she fell in love" ... the first one means "she is in love" while the second one just talks about some of her history. |

|

| |

|

| '''glàs baú timpori''' = The woman hit the man

| | Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London". |

|

| |

|

| '''glà baús timpori''' = The man hit the woman | | Easy to translate into English ... '''doikorwi''' = He/she had walked ... '''doikorwa''' = He/she has walked ... '''doikorwu''' = He/she will have walked |

|

| |

|

| It can be seen that "'''s'''" is added to the "doer" of the action.

| | The next row expresses the "not yet" tense. |

|

| |

|

| .. | | Easy to translate into English ... '''doikoryi''' = He/she had not yet walked ... '''doikorya''' = He/she hasn't walked yet ... '''doikoryu''' = He/she will not have walked |

|

| |

|

| However consider the clause below ...

| | Notice that the English translation, '''doikoryu''' is just the negative of '''doikorwu'''. Interesting eh ? In fact these two aspects can be in many ways regarded as the negatives of each other, although in English only the future tense gives the surface forms this way. |

|

| |

|

| .. | | Which leads us on to the next row. This row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2 (that is right, row 2 does not have its own negative). |

|

| |

|

| '''glà doikor''' = The woman walks | | Just as '''-rna''' does not specify the present tense but instead gives a tenseless habitual, '''-rka''' gives a tenseless negative. |

|

| |

|

| It can be seen that the "doer" does not have an attached "'''s'''" in this case.

| | Easy to translate into English ... '''doikorki''' = He/she didn't walk ... '''doikorka''' = He/she doesn't walk ... '''doikorku''' = He/she will not walk |

|

| |

|

| The reason is that "to walk" is an intransitive verb while "to hit" is a transitive verb

| | You may have noticed that the '''béu''' letter that negates verbs is very similar to the Chinese character that negates verbs ('''bù'''). This is pure coincidence. |

|

| |

|

| It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument.

| | By the way, the '''béu''' terms for the five aspects represented by these 5 rows are ... '''baga''', '''dewe''', '''pomo''', '''fene''', and '''liʒi'''. |

|

| |

|

| It is the convention to call the "doer" in a transitive clause the A argument and the "done to" the O argument.

| | <sup>*</sup>But even with 16 tense/aspect markers, not EVERY situation can be exactly expressed. |

|

| |

|

| A language that has the S and O arguments marked in the same way is called an ergative language

| | For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out" (using the progressive plus the perfect aspects). The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" (or working out over some period of time) to build up muscles. '''béu''' has no tense/aspect marker so appropriate. |

|

| |

|

| If you like you can say ;-

| | Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance. |

|

| |

|

| In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument).

| | By the way, in the above example, the muscular schoolmate would use the '''r''' form of the verb plus the '''béu''' equivalent of "now", to explain his present condition. Good enough. |

| | |

| In '''béu''' '''ò''' is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : '''ós''' is the "doer to"(A argument).

| |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| == ..... Transitivity and the very useful word "é" == | | === ... Slot 3 === |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

|

| |

|

| In '''béu''' a verb is either transitive or intransitive. There is no "ambitransitive verbs as in English.<sup>*</sup>

| | 4) and finally one of the 4 '''teŋko'''-markers shown below is added. |

|

| |

|

| For example ... in English, you can say ... "I will drink water" or simply "I will drink"

| | [[Image:TW_122.png]] |

|

| |

|

| The second option is not allowed in '''béu''' ... as "drink" is a transitive verb, you must say "I will drink something" = '''solbaru é'''

| | '''teŋkai''' is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate" ... '''teŋko''' is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence". |

|

| |

|

| Well actually you can, the '''é''' can be dropped ... just as easily as the '''pás''' is dropped. The point is that the listener "knows" that there are always 2 arguments. The same can not be said in English when you here "he drinks" ... it could mean that the subject habitually drinks alcohol, in which case we have only one S argument.

| | About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. As evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In '''béu''' there are 4 evidential suffixes. One is what is called a zero suffix. And in meaning it gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based. |

|

| |

|

| For another example ... in English, you can say ... "the woman closed the door" or simple "the door closed".

| | a) '''doikori''' = He/she walked ... this is neutral. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is saying what he is saying. |

|

| |

|

| The second option is not allowed in '''béu''' ... as "close" is a transitive verb, you must say "something closed the door" = '''pintu nagori és'''

| | b) '''doikorin''' = They say he/she walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so. |

|

| |

|

| (Actually there is another option for expressing the above ... you can change any transitive verb to an intransitive verb ... '''pintu nagwori''' = "the door was closed"

| | c) '''doikoris''' = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow. |

|

| |

|

| .. | | The above 2 '''tenko''' are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form ('''doikori'''). The fourth '''tenko''' on the contrary, introduced more certainty. |

|

| |

|

| If an argument is definite in '''béu''' it is usually comes before the verb, and if indefinite it usually comes after the verb.

| | d) '''doikoria''' = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself". |

|

| |

|

| Now the word '''é''' is by definition indefinite. It actually means "somebody" OR "something". What happens if this word is put before the verb.

| | This last '''teŋko''' can only be used with one of the '''gwomai''' . It can ONLY be used with the plain passed tense form '''i'''. |

|

| |

|

| Well something quite interesting happens ... '''é''' changes into a question word meaning "who" or "what"

| | An '''o''' is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s". |

| | |

| For example ... '''és pintu nagori''' = Who/what closed the door

| |

| | |

| For another example ... "what will I drink" = '''é solbaru'''

| |

| | |

| And yet another one ... "who drank the water" = '''és moze solbori'''

| |

|

| |

|

| .. | | .. |

| | | == ... Index== |

| <sup>*</sup>Actually you can tell the transitivity of a verb (for a word of more than one syllable) by looking at its last consonant. If the last consonant is '''j b g d c s k''' or '''t''' then it is transitive. If it is '''ʔ m y l p w n''' or '''h''' it is intransitive.

| |

| | |

| There is about 300 words that have an intransitive form as well as a transitive form, only differing in their final consonant. The relationship between these final consonants is shown below. '''x''' means "any vowel".

| |

| | |

| | |

| {| border=1

| |

| |align=center| transitive

| |

| |align=center| intransitive

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-jx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-lx'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-bx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-ʔx'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-gx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-mx'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-dx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-yx'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-cx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-wx'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-sx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-nx'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-kx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-hx'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''-tx'''

| |

| |align=center| '''-lx'''

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| NB ... '''y''' and '''w''' are usually not allowed to be the second element in a word ... but in these special words, they are.

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| == ..... Independent specifiers==

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| '''koiʒi''' actually means "preface" as in "the preface to the book"

| |

| | |

| Also means forewarning or harbinger ... as in "that slight tremor on Tuesday night, was '''koizi''' of the quake on Friday"

| |

| | |

| All words that can occur to the right of the head in a NP are called '''nandaua koiʒi''' or ... when talking about grammar ... usually just '''koiʒia'''

| |

| | |

| These words include the numbers from 1 to 1727, the words "few" and "many", and the words below.

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| {| border=1

| |

| |align=center| '''jù'''

| |

| |align=center| no

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''í'''

| |

| |align=center| any

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''é'''

| |

| |align=center| some (singular)

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''éu'''

| |

| |align=center| some (plural)

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''ù'''

| |

| |align=center| all

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''yú'''

| |

| |align=center| each/every

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| These words can also constitute a NP in themselves. When they do that, the table below gives their translations into English.

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| {| border=1

| |

| |align=center| '''jù'''

| |

| |align=center| nobody/nothing/none

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''í'''

| |

| |align=center| anybody/anything

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''é'''

| |

| |align=center| somebody/something

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''éu'''

| |

| |align=center| some people/somethings

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''ù'''

| |

| |align=center| everybody/everything

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| '''yú'''

| |

| |align=center| everybody/everything

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| ..

| |

| | |

| NB ... It should be remembered that '''é''' and '''éu''', in certain circumstances can mean "what" or "who"

| |

| | |

| == ..... More about the '''pilana''' ==

| |

| | |

| ==='''-pi''' or '''pì'''===

| |

| | |

| '''meu (rà)''' "basket"'''pi'''

| |

| | |

| While the original meaning was about space, this '''pilana''' is very often found referring to time.

| |

| | |

| I read the book hour'''pi''' => I read the book in an hour

| |

| | |

| I gets dark '''pi''' ten minutes => It get dark in ten minutes

| |

| | |

| She qualified as a doctor '''pi''' five years

| |

| | |

| One can get from Glasgow to London day'''pi'''

| |

| | |

| I'm coming to Sweden '''pi''' next month

| |

| | |

| -------------------

| |

| | |

| '''meu (rà)''' top'''la''' basket'''n''' = The cat is on top of the house

| |

| | |

| '''meu (rà)''' interior basket'''n''' = the cat is in the basket

| |

| | |

| ----------------------------

| |

| | |

| ==='''-la''' or '''lá'''===

| |

| | |

| mat (rà) floor'''la''' => the mat is on the floor ... notice "the mat"

| |

| | |

| '''twor''' mat floor'''la''' => there is a mat on the floor ... notice "a mat". Also the verb '''two''' is usually sentence initial, at least when introducing something new.

| |

| | |

| '''meu''' (rà) top'''la nambon''' => The cat is on top of the house

| |

| | |

| Notice that "top'''la nambon'''" is allowed, I should mention this somewhere.

| |

| | |

| | |

| '''twor ble pàn''' = I have (some) money

| |

| | |

| '''ble twor pàn''' = I have the money

| |

| | |

| '''tworka ble pàn''' = I don't have any money .... Note that it is also possible to say '''twor yà ble pàn''', but the first method is definitely preferred.

| |

| | |

| '''ble tworka pàn''' = I don't have the money

| |

| | |

| ---------------

| |

| | |

| bird '''(rà)''' top '''nambon''' = The bird is above the house

| |

| | |

| Notice that in the above example "top" is considered a specifier ... "top '''nambo'''" forms a tight compound.

| |

| | |

| The eight specifiers of location are above, below, right, left, this side (with respect to the speaker, of course), the far side

| |

| | |

| | |

| '''yè''' and '''fí''' are not used for locations. Instead the transitive verbs "arrive" and "leave" are used in a SVC.

| |

| | |

| Also the words "come" and "go" covered by "arrive" and "leave".

| |

| | |

| When not talking about location, '''yè''' and '''fí''' are used.

| |

| | |

| For example ...

| |

| | |

| She gave food to the beggar = ...... beggar'''ye'''

| |

| | |

| The beggar got food from the woman = ...... waman'''fi'''

| |

| | |

| Verbs such as hear and tell use these '''pilana''' also.

| |

| | |

| Also such sentences as ...

| |

| | |

| I was made to sing by the guard = I receive sing guard'''fi'''

| |

| | |

| He made the prisoner sing = He give sing prisoner'''ye'''

| |

| | |

| Also such sentences as ...

| |

| | |

| He went from being very rich, to very poor, within six months

| |

| | |

| use '''yè''' and '''fí'''

| |

| | |

| ==='''-ye''' or '''yè'''===

| |

| | |

| '''kyiwa toili oye''' = give the book to her

| |

| | |

| This is the '''pilana''' used for marking the receiver of a gift, or the receiver of some knowledge.

| |

| | |

| However the basic usage of the word is directional.

| |

| | |

| '''*namboye''' = "to the house"

| |

| | |

| distance'''ye nambon''' = "as far as the house"

| |

| | |

| "limit"'''ye nambon''' = "up to the house" ... this usage is not for approaching humans however ... for that you must use "face".i.e. "face"'''ye báun''' = right up to the man

| |

| | |

| | |

| -----------------------

| |

| | |

| '''yèu''' = to arrive ... '''yài''' a SVC meaning "to start" ... '''fái''' a SVC meaning "to stop" ???

| |

| | |

| -----------------

| |

| | |

| ==='''-fi''' or '''fí'''===

| |

| | |

| '''nambofi''' = "from the house"

| |

| | |

| '''fí "direction" nà nambo''' = "away from the house" i.e.you don't know if this is his origin but he is coming from the direction that the house is in.

| |

| | |

| '''fí "limit/border" nà nambo''' = all the way from the house

| |

| | |

| '''fí "top" nà nambo''' = from the top of the house ... and so on for "bottom", "front", etc. etc.

| |

| | |

| he changed frog.'''fi''' '''ye''' prince handsome = he changed from a frog to a handsome prince

| |

| | |

| -----------------------

| |

| '''fía''' = to leave, to depart ... '''fái''' a SVC meaning "to finish" .... then '''bai''' cound mean continue and '''-ana''' would be the present tense ???

| |

| | |

| -----------------

| |

| | |

| ==='''-lya''' or '''alya'''===

| |

| | |

| Sometimes called the "Allative case". Can be said to translate to English as "onto".

| |

| | |

| The '''x''' means that the previous vowel is repeated.

| |

| | |

| '''xxx yyy zzz''' = put the cushions on the sofa

| |

| | |

| -----------------------

| |

| | |

| ==='''-lfe''' or '''alfe'''===

| |

| | |

| The ablative

| |

| | |

| ==='''-s''' or '''sá'''===

| |

| | |

| that Stefen turned up drunk at the interview sank his chance of getting that job

| |

| | |

| '''sá tá ........ '''

| |

| | |

| ==='''-ce''' or '''cé'''===

| |

| | |

| The instrumental is used for nouns that represent the instrument ("with"), the means ("by") or the agent ("by").

| |

| | |

| John writes with a pen

| |

| | |

| banu = to learn

| |

| | |

| banuge = by learning

| |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| book was written '''page''' = The book was written by me

| |

| | |

| '''andage''' = manually

| |

| | |

| I work as a translator ??? ... I work '''sàu''' translator ??

| |

| | |

| '''gé ta ... '''

| |

| | |

| ==='''-ho''' or '''hò''' ===

| |

| | |

| The commitive

| |

| | |

| "in the company of", often used with the personal pronouns ;-

| |

| | |

| {| border=1

| |

| |align=center| with me

| |

| |align=center| '''paho'''

| |

| |align=center| with us

| |

| |align=center| '''yuaho'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center|

| |

| |align=center|

| |

| |align=center| with us

| |

| |align=center| '''wiaho'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| with you

| |

| |align=center| '''giho'''

| |

| |align=center| with you (plural)

| |

| |align=center| '''jeho'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| with him, with her

| |

| |align=center| '''oho'''

| |

| |align=center| with them

| |

| |align=center| '''uho'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| with it

| |

| |align=center| '''ʃiho'''

| |

| |align=center| with them

| |

| |align=center| '''ʃiho'''

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| -----------------------

| |

| '''tùa''' = to use, to wear ... '''tàu''' a SVC meaning ??

| |

| | |

| ==='''-ji''' or '''jí'''===

| |

| | |

| The benefactive. Sometimes used with '''gomia'''

| |

| | |

| banu = to learn, banuji = in order to learn

| |

| | |

| ==='''-wo''' or '''wó'''===

| |

| | |

| Not used for the locative sense of about, it has the sense "with respect to" more. Used for example when have the word '''halfa''' = to laugh.

| |

| | |

| 1) '''pà halfari''' = I laught

| |

| | |

| 2) '''pà halfari jonowo''' = I laught at John

| |

| | |

| Is 2) a transitive verb ? Semantically transitive maybe ... but (in English and in '''béu'''), John is introduced by a preposition ... so I guess 2) is not transitive ???

| |

| | |

| 2) '''pà halfari jonoye''' = I taunted John

| |

| | |

| Used for marking the "theme" as in such sentences as the one below.

| |

| | |

| '''gala caturi jonowo''' => The women were talking about John

| |

| | |

| '''jonowo''' ... = as for John ....

| |

| | |

| ==='''-n''' or '''nà'''===

| |

| | |

| The locative or the possessive. Basically if the noun is human, it is the possessive : if the noun is non-human, it is locative.

| |

| | |

| '''nambo jonon (rà) hauʔe''' = John's house is beautiful

| |

| | |

| '''jono (rà) nambon''' = John is at home

| |

| | |

| == ..... Index==

| |

|

| |

|

| {{Béu Index}} | | {{Béu Index}} |

..... The R-form of the verb

..

Now we should introduce the active forms of the verb (also referred to as the R-form). béu has quite a comprehensive set of tense/aspect markers. The active form of the verb is built up from the infinitive form. There is only one infinitive in béu.

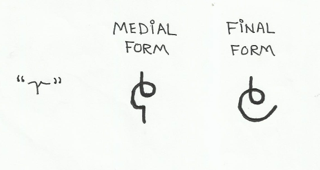

We will discuss the most-used form of the verb in this section, the R-form. But first we should introduce a new letter.

..

..

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the R-form of the verb.

So if you hear "r" or see the above symbol, you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause. (definition of a clause (semo) = that which has one "r" ... ??? )

O.K. ... the R-form is built up from the infinitive*.

1) First the final vowel is deleted.

*Excepts in rare cases (see "Adjectives and how they pervade other parts of speech")

..

... Slot 1

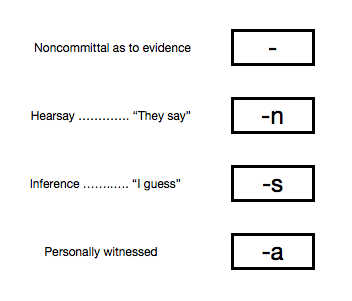

..

2) one of the 7 vowels below is added.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the Western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she). In the béu linguistic tradition they are called cenʔo-markers. (cenʔo = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play)

These markers represent the subject (the person that is performing the action). Whenever possible the pronoun that represents the subject is dropped, it is not needed because we have that information inside the verb with the cenʔo-markers.

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one must be used when the people performing the action included the speaker, the spoken to and possibly others. The lower one must be used when the people performing the action include the speaker, NOT the person spoken to and one or more 3rd persons.

Note that the ai form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

..

... Slot 2

..

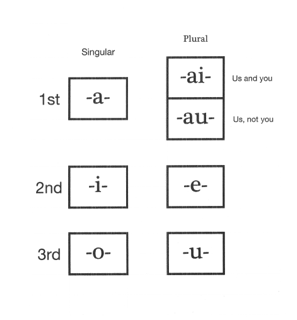

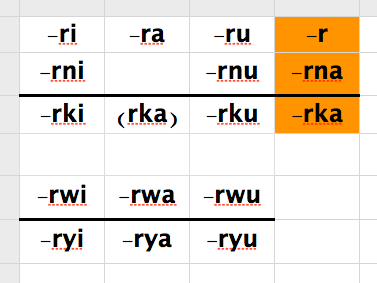

3) now one of the 16 markers shown below is added. 16 is quite a respectable number, as far as tense/aspect markers go.*

Now these markers represent what are called tense/aspect markers in the Western linguistic tradition. In the béu linguistic tradition, they are called gwomai or "modifications". (gwoma = to alter, to modify, to adjust, to change one attribute of something).

The table above has the gwoma arranged according to form. The two arrays below have the gwoma arranged according to meaning. The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. An orange background indicates the timeless tense. You can see I have one entry enclosed by brackets. That is because to give a negative present tense negative you would express it periphrastically ... you would use the tenseless negative -rka followed by the béu equivalent of "now" or "at the moment".

Looking at the upper table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... i for the past, a for the present and u for the future.

-ri ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

-ra ... Should only be used if the action is happening NOW. English uses "to be xxxing". For example doikara = I am walking ... (doika = to walk)

-ru ... This is the future tense.

-r ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly".

The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school), Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). Actually in béu the pattern is broken a bit, in that -rna has NOTHING to do with the activity going on at the time of speech, it is actually a tenseless habitual. Also béu and English behave the same in the following way ... whereas by logic we should use doikarna in "I walk (to school everyday)", in fact doikar is used. doikarna would be used only if we were going on to MENTION some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift)

doikarna = "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use doikar

-rnu ... Now English doesn't have a future habitual. But if it did it would have a roll. For instance, suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In béu you would answer doikarnu.

The next row expresses the perfect tense.

While the perfect tense, logically this doesn't have that much difference from the past tense it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John. And think about the difference in meaning between "she has fallen in love" and "she fell in love" ... the first one means "she is in love" while the second one just talks about some of her history.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

Easy to translate into English ... doikorwi = He/she had walked ... doikorwa = He/she has walked ... doikorwu = He/she will have walked

The next row expresses the "not yet" tense.

Easy to translate into English ... doikoryi = He/she had not yet walked ... doikorya = He/she hasn't walked yet ... doikoryu = He/she will not have walked

Notice that the English translation, doikoryu is just the negative of doikorwu. Interesting eh ? In fact these two aspects can be in many ways regarded as the negatives of each other, although in English only the future tense gives the surface forms this way.

Which leads us on to the next row. This row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2 (that is right, row 2 does not have its own negative).

Just as -rna does not specify the present tense but instead gives a tenseless habitual, -rka gives a tenseless negative.

Easy to translate into English ... doikorki = He/she didn't walk ... doikorka = He/she doesn't walk ... doikorku = He/she will not walk

You may have noticed that the béu letter that negates verbs is very similar to the Chinese character that negates verbs (bù). This is pure coincidence.

By the way, the béu terms for the five aspects represented by these 5 rows are ... baga, dewe, pomo, fene, and liʒi.

*But even with 16 tense/aspect markers, not EVERY situation can be exactly expressed.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out" (using the progressive plus the perfect aspects). The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" (or working out over some period of time) to build up muscles. béu has no tense/aspect marker so appropriate.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

By the way, in the above example, the muscular schoolmate would use the r form of the verb plus the béu equivalent of "now", to explain his present condition. Good enough.

..

... Slot 3

..

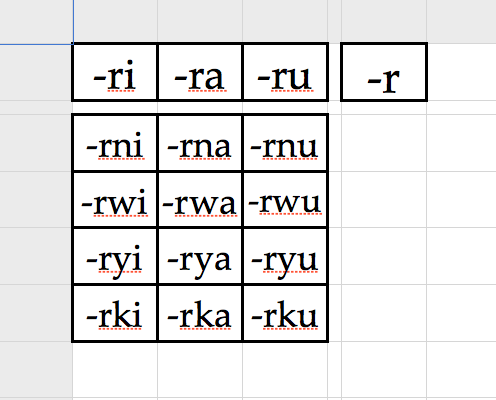

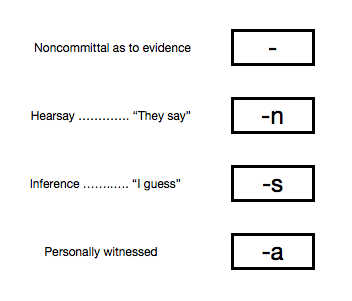

4) and finally one of the 4 teŋko-markers shown below is added.

teŋkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate" ... teŋko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. As evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In béu there are 4 evidential suffixes. One is what is called a zero suffix. And in meaning it gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based.

a) doikori = He/she walked ... this is neutral. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is saying what he is saying.

b) doikorin = They say he/she walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

c) doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow.

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The fourth tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

d) doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself".

This last teŋko can only be used with one of the gwomai . It can ONLY be used with the plain passed tense form i.

An o is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s".

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences