|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| ===Word generation===

| |

|

| |

|

| In the word generating program ;-

| | == ..... Note ..... == |

|

| |

|

| 17 % chance that a word will start with a vowel

| | Stuff discarded before 28th Mar 2013 is in chapter XX |

|

| |

|

| 83 % chance that it will start with a consonant.

| | Stuff discarded after 28th Mar 2013 is in this chapter. |

|

| |

|

| 10 % chance that the second consonant will be lʔ ... lh

| | == ..... Pronouns == |

|

| |

| 50 % chance that the second consonant will be ʔ ... l

| |

|

| |

|

| 31 % chance that the second consonant will be nʔ ... nh

| | In this section we discuss pronouns and also introduce the S, A and O arguments. |

|

| |

|

| 9 % chance that the second consonant will be sʔ ... sh

| | '''béu''' is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings (in English there is a fixed word order, which also helps. In '''béu''' the word order is free). |

|

| |

|

| === Complement clause ... relative clause === | | '''timpa''' = to hit ... '''timpa''' is a verb that takes two nouns (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb). |

|

| |

|

| Originally I had the relativizer and the complementiser the same ... '''tà'''

| | '''pás ò timpari''' = I hit him |

| | '''pà ós timpori''' = He hit me ... OK in this case the protagonist marking in the verb also helps to make things disambiguous. But this will not always help, for example when both protagonists are third person and of the same number. |

|

| |

|

| MAYBE WE SHOULD CHANGE THE RELATIVE CLAUSE MARKER TO "SÀ". THIS IS BECAUSE DUE TO THE FREE WORD ORDER IN BEU, "THAT" OF A COMPLEMENT CLAUSE DOESN'T ALWAYS FOLLOW THE VERB AS IN ENGLISH, BUT CAN FOLLOW A NOUN ??

| | So far so good. And we see that English and '''béu''' behave in the same way so far. But what happens when we take a verb that takes only one noun (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb). For example '''doika''' = "to walk". In English we have "he walked". However in '''béu''' we don't have '''*ós doikori''' but '''ò doikori''' (equivalent to saying "*him walked" in English). So this in a nutshell is what an ergative language is. |

|

| |

|

| '''kolape''' is when a clause is modified slightly and functions either as an adjective modifying a noun (a relative clause) or as a noun being one of the core arguments in another clause.

| | It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument. For example '''ò<sub>S</sub> fomporta''' = She has tripped |

| '''kolape saidau''' is a relative clause construction which works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. A relative clause is a clause that qualifies a noun. It is introduced by a special particle, '''tà''' in '''béu'''. In English it is usually "that" but a number of other words can also be used.

| |

|

| |

|

| == ..... How to ask a content question==

| | It is the convention to call the "doer" in a transitive clause the A argument and the "done to" the O argument For example '''ós<sub>A</sub> timpori jene<sub>O</sub>''' = He hit Jane |

|

| |

|

| All content questions have the particle '''cù''' at the beginning of the sentence.

| | The S was historically from the word "Subject" and the O historically from the word "Object", but it is best just to forget about that. In fact when I use the word "subject" I am talking about either the S argument or the A argument. |

|

| |

|

| Also we must have one of the six interrogative words just after the '''cù'''. These more The most common of these interrogative words is '''ʔái''' which means "what" or "which" or "who" (it depends on the context).

| | If you like you can say ;- |

|

| |

|

| Notice that this is the same as the tag that we use to form a yes/no question. Another use of this word is as a nominalizer. In fact this word is so common that a shorthand way is used to write it. '''cù''' also has a shorthand form. Both these shorthand forms are shown below. Also the case ending on '''glá''' is written n a truncated way.

| | In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument). |

|

| |

|

| -----------------

| | In '''béu''' '''ò''' is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : '''ós''' is the "doer to"(A argument). |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:TW_153.png]]

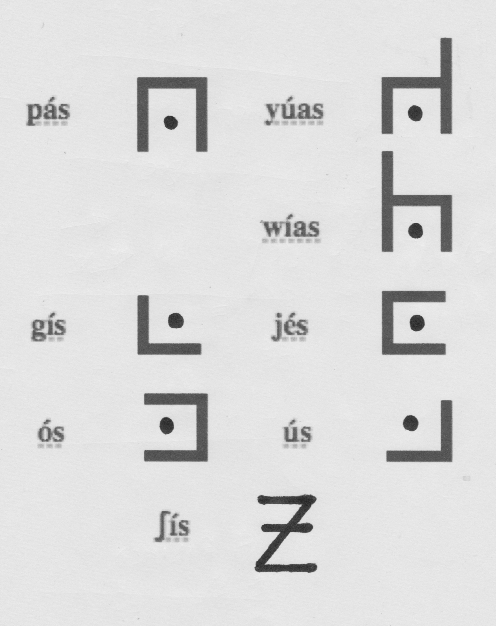

| | Below the form of the '''béu''' pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the A argument. |

| | |

| '''cù ʔái báus glaye kyori''' = what did the man give to the woman | |

| | |

| -----------------

| |

| | |

| === Personel possessives ===

| |

| | |

| In the above section we learnt how to say "mine", "yours", etc. etc.. But how do we say "my", "your", etc. etc.

| |

| | |

| Well these words (which would be considered adjectives in the '''béu''' linguistic tradition) are represented by infixes. The table below shows how it works.

| |

|

| |

|

| {| border=1 | | {| border=1 |

| |align=center| my coat | | |align=center| I |

| |align=center| '''kaunapu''' | | |align=center| '''pás''' |

| | |align=center| we (includes "you") |

| | |align=center| '''yúas''' |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| our coat ("our" includes "you") | | |align=center| |

| |align=center| '''kaunayu''' | | |align=center| |

| | |align=center| we (doesn't include "you") |

| | |align=center| '''wías''' |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| our coat ("our excludes "you") | | |align=center| you |

| |align=center| '''kaunawu''' | | |align=center| '''gís''' |

| | |align=center| you (plural) |

| | |align=center| '''jés''' |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| your coat | | |align=center| he, she |

| |align=center| '''kaunigu''' | | |align=center| '''ós''' |

| | |align=center| they |

| | |align=center| '''ús''' |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| your coat (with "you" being plural) | | |align=center| it |

| |align=center| '''kauneju''' | | |align=center| '''ʃís''' |

| |-

| | |align=center| they |

| |align=center| his/her coat

| | |align=center| '''ʃís''' |

| |align=center| '''kaunonu'''

| | |} |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| their coat

| |

| |align=center| '''kaununu'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| xxxx own coat | |

| |align=center| '''kaunitu''' | |

| |}

| |

|

| |

|

| It can be seen that the infixes are the same as the plain pronouns, but the order of the consonant and vowel are swapped over.

| |

|

| |

|

| There could also be another entry in the table above. That is the infix '''-it-''' (this is the possessive equivalent of the reflexive pronoun '''tí''' (see above). It is probably easiest to explain '''-it-''' by way of example;-

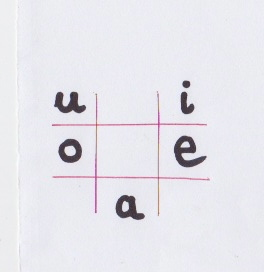

| | [[Image:TW_68.png]] |

|

| |

|

| '''polo hendoru kaunitu''' = Paul will wear his coat (To be absolutely specific "Paul will wear his own coat")

| | However these pronouns are never written out as above. There is a recognized "shorthand" method of writing them. This is shown below. |

|

| |

|

| '''polo hendoru kaunonu''' = Paul will wear his coat (To be absolutely specific "Paul will wear someone else's coat")

| | [[Image:TW_161.png]] |

|

| |

|

| A thing to note is that you can not insert an infix into a monosyllable word. You could not say '''*glapa''' for "my woman" but would have to say '''glá nà pà'''

| | This method is based on the fact that all the pronouns have a different vowel sound (the ones that refer to humans anyway). A look at a béu vowel chart might let you work out what is happening here. |

| | |

| ==Hi-lighting a question topic==

| |

| | |

| In the last section we saw how to focus on a particular element in a normal declarative statement. There is a special way to focus on a particular element in a YES/NO question..

| |

| | |

| If you want to query a particular element in the clause and not the clause as a whole, you stick '''ʔói''' on to the element that you want to query. For example ...

| |

| | |

| 1) '''glà timpori ʔói báus''' = Did a man '''hit''' the woman ? (I thought that he had kicked her)

| |

| | |

| 2) '''glà timpori baus ʔói''' = Was it '''a man''' that hit the woman ? (I thought it was a boy)

| |

| | |

| 3) '''glà ʔói timpori baus''' = Was it '''a woman''' that the man hit ? (I thought it was a ladyboy)

| |

| | |

| And indeed a whole noun phrases can be brought into interrogative focus this way. For example ...

| |

| | |

| '''sá báu jutu dè ʔói timpori jene''' = was it the big guy that hit Jane. .... (notice the inclusion of '''dè''' when you do this, an item that would not normally to included)

| |

| | |

| But it is not possible to focus on an element within a noun phrase.

| |

| | |

| ==='''-co''' or '''có'''===

| |

| | |

| '''pilana najauva''' ... (the fourteenth pilana)

| |

| | |

| means "about" as in "they talk about him".

| |

| | |

| can mean "with respect to"

| |

| | |

| a general preposition

| |

| | |

| often in English a preposition is used to make a transitive verb => intransitive verb

| |

| | |

| for example THINK => THINK ABOUT

| |

| | |

| Esperanto .... Fijian

| |

| | |

| == ..... Question Words==

| |

| | |

| OK The latest is now ....

| |

| | |

| A yes/no question is shown by ʔá at the end of the sentence. | |

| | |

| Content questions are shown by '''ʔái''' what, who, which : '''mái''' where : '''yái''' when : '''wái''' why : '''nái''' how much : '''hái''' how ... these are not necessarily fronted.

| |

| | |

| The following could be considered some sort of nominalizers.

| |

| | |

| '''ʔà''' = "that which" or simply "what" as in "what you need is love".

| |

| | |

| '''mài''' = "the place where" or simply "where"

| |

| | |

| '''yài''' = "the time when" or simply "when"

| |

| | |

| etc. etc.

| |

| | |

| These can also function as relativizers also. Well one way to analyse it, is to say that they are nominalizers, and that a relative clause is simply a nominal that stands in apposition to the qualified noun.

| |

| | |

| To question individual elements.

| |

| | |

| It was John that hit Jane = '''jonos lá timpori jene''' .... '''béu''' uses '''lá''' for emphasis .... English uses Left Dislocation, as exhibited at the beginning of this line.

| |

| | |

| And there is a polar question that mirrors the above construction.

| |

| | |

| Was it John that hit Jane ? = '''jonos lái timpori jene'''

| |

| | |

| Also we have a question verb ... '''laiʔ-''' (I don't know if you would ever see the '''gomia''' of this word ???) ... For example ... '''laiʔiri''' = "what did you do"

| |

| ----------------------

| |

| | |

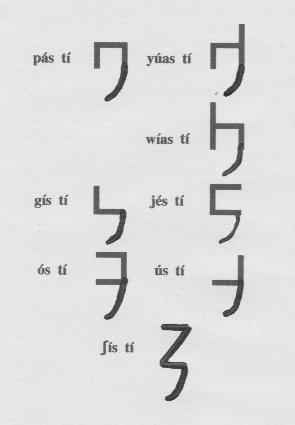

| In a similar manner to the '''pilana''' not being written out in full, the 6 '''béu''' question words have a sort of "shorthand" notation.

| |

| | |

| See below ...

| |

| | |

| | |

| [[Image:TW_128.png]]

| |

| | |

| [[Image:TW_129.png]]

| |

| | |

| | |

| It can be seen that the form for "what" is how you might write '''ʔa''' if you were in a hurry.

| |

| | |

| The other 5 words are based on this "what" form.

| |

| | |

| The form for '''ʔáu''' can be seen to simply add the stoke that represents the '''u''' in the full form.

| |

| | |

| The form for '''ʔái''' in a similar manner adds a stroke, but has twists it around a bit to make the character look better.

| |

| | |

| The form for '''ʔawe''' incorporates a stroke that echoes a part of the full form.

| |

| | |

| The form for '''ʔalo''' in a similar manner incorporates a stroke that echoes part of the full form, but straightens it out to make the character look better.

| |

| | |

| The form for '''ʔaja''' doesn't echo the full form. Instead it is iconic.

| |

| | |

| If you remember that "which" is equivalent to "what one", then the dot placed below the "what" flourish can be understood to represent "one".

| |

| | |

| As with English, these question words are always fronted.

| |

| | |

| We have seen already that the quantifiers/specifiers and the determiners can either stand alone or occur along with a noun. (but when the noun is dropped it is probably/always ?? understood from context)

| |

| | |

| In the same way '''ʔá''' can appear by itself or occur along with a noun. However when the noun is dropped it is NOT known from the context ... ( or an alternative analysis is that the noun IS known from the context, but it is that most generic of all nouns ... "thing").

| |

| | |

| Here are some examples ...

| |

| | |

| 1) '''báus timpi glà''' = the man hit a woman

| |

| | |

| 2) '''ʔás báus glà timpi''' = what man hit the woman

| |

| | |

| 3) '''ʔás glà timpi''' = what/who hit the woman

| |

| | |

| 4) '''ʔá glà báus timpi''' = "what woman did the man hit" or using the passive "what woman was hit by the man"

| |

| | |

| 5) '''ʔá báus timpi''' = "what/who did the man hit" or using the passive "what/who was hit by the man"

| |

| | |

| We can see in 2) that both parts of the NP "what man" take the ergative '''pilana'''.

| |

| | |

| This is the only '''pilana''' that behaves in this way. For the other '''pilana''' the free-standing form is put before '''ʔá'''. For example...

| |

| | |

| 6) '''yè ʔá toili kyiri''' = who did you give the book to

| |

| | |

| The word '''ʔán''' comes before the noun that it qualifies. It normal circumstances the genitive comes after.

| |

| | |

| ==The topic marker "'''wa'''" and the discourse strategy of dropping the topic.==

| |

| | |

| I THOUGHT THAT THIS WAS A PRETTY NEAT IDEA FOR A TIME. IT ALLOWS PRONOUN DROPPING BUT FOR THIS PRONOUN DROPPING, YOU MUST GET RID OF ALL AMBITRANSITIVE VERBS (SUCH AS "TURN TO". I DECIDED THAT I WANTED AMBITRANSITIVE VERBS, HENCE THIS WHOLE IDEA OF PRONOUN DROPPING USING "WA" WOULD NOT WORK.

| |

| | |

| English has what Dixon calls a S/A pivot construction. What that means is you can drop the A argument or the S argument if it is the same as the A argument or S argument in the previous clause. For example ;-

| |

| | |

| 1) You can drop the A if it is the same as the S in the previous clause ... John saw Mary: John laughed => John saw Mary and laughed

| |

| | |

| 2) You can drop the A if it is the same as the A in the previous clause ... John saw Mary : John hit Bill => John saw Mary and hit Bill

| |

| | |

| 3) You can drop the S if it is the same as the S in the previous clause ... John entered : John sat down => John entered and sat down

| |

| | |

| 4) You can drop the S if it is the same as the A in the previous clause ... John entered : John saw Mary => John entered and saw Mary

| |

| | |

| A small number of languages have a S/O pivot. That is you can drop the S argument or the O argument if it is the same as the S argument or O argument in the previous clause. (the Australian language Dyirbal is one example of this type of language).

| |

| | |

| Anyway, the above is just some side-information that I am giving you.

| |

| '''béu''' has what I call a declared pivot construction. The "pivot" (or topic) in a discourse must be stated and from that point on all reference to that "pivot" is dropped, until a new "pivot" is declared.

| |

| | |

| You declare the topic by affixing '''wa''' to it when it is in S, A or O function. If it is in A function that the topic is declared then the '''s''' (ergative marker) is dropped. (However in the clause in which you declare a pivot can not have any dropped arguments ... if it is a transitive verb in the clause, and there in no argument with the ergative marker, then you can work out that it must be the argument marked by '''wa''' which is the A argument). From then on the topic is dropped until a new topic is declared. For example;-

| |

| | |

| 1) giant.'''wa''' destroyed the castle on the hill

| |

| | |

| 2) Then '''ø''' came down into the valley

| |

| | |

| 3) There '''ø''' met a dwarf doing good works

| |

| | |

| 4) The dwarf turned '''ø''' to stone

| |

| | |

| 5) Dwarf.'''wa''' then climbed the mountain

| |

| | |

| 6) '''ø''' gave succour to the people from the castle ...

| |

| | |

| It is the rule that the topic must be dropped. if the topic appears in a peripheral roll (pilana 1-> 14) then that '''pilana''' is attached to the verb.

| |

| | |

| For example ;-

| |

| | |

| 1) Last night I saw Thomas

| |

| | |

| 2) Thomas.wa (or '''o.wa''') was very drunk

| |

| | |

| 3) Mary had given.'''ye''' a bottle of Chevas Regal

| |

| | |

| How does this system mesh in with passives ? Particles that appear between clauses ? Particles that change the subject ?

| |

| | |

| You can see from 4) above, that this just doesn't work if you have labile verbs. In English "turned" is called a labile verb (ambitransitive is another name for this). That means it can be used in a transitive clause and in an intransitive clause. Foer example ;-

| |

| | |

| 1) The dwarf turned the giant to stone ... transitive

| |

| | |

| 2) The dwarf turned to stone ... intransitive

| |

| | |

| === Some Rubbish ===

| |

| | |

| == ..... How to focus on a particular element==

| |

| | |

| Well we can "front" the element using a relative clause (as we do in English).

| |

| | |

| '''ʃí (ro/ri) glà tà báus timpori''' = "It is/was it a/the woman that the man hit" .... statement

| |

| | |

| Another method is to speak a slower (clearer) and a bit louder when you come to the element that you want to focus. This is represented in the orthography by making the font of the emphasised word 150%.

| |

| | |

| '''pàs JENE timpari''' = It was '''Jane''' that I hit (it wasn't Mary)

| |

| | |

| '''pàs JENE timparki''' = It wasn't '''Jane''' that I hit (it was Mary)

| |

| | |

| === ..... '''gaza''' ... the copula of existence===

| |

| | |

| The copula complement of '''gaza''' ia always a noun or a noun phrase. It is how you say "there is ... "

| |

| | |

| '''gaza''' is similar to '''sàu''' in that it takes the 9 verb modifiers but 3 of them are wildly irregular. It is the same 3 tense/aspect forms that are irregularin the '''sàu''' copula. Namely ;-

| |

| | |

| '''*gazora''' => '''ʔá''' meaning "there is"

| |

| | |

| '''*gazori''' => '''ʔái''' meaning "there was"

| |

| | |

| '''*gazoru''' => '''ʔáu''' meaning "there will be"

| |

| | |

| Actually while theoretically '''gaza''' can have the full range of modifiers enjoyed by a normal verb, in reality all forms other than '''ʔá''', '''ʔái''', '''ʔáu''' are extremely rare. Occasionally you come across the "infinitive" '''gaza'''.

| |

| | |

| There is no word that corresponds to "have". The usual way to say "I have a coat" is "there exists a coat mine" = '''ʔá kaunu nà pà'''

| |

| | |

| Internal possessives are not allowed in the nouns introduced with '''gaza'''. That is, you can not say '''*ʔá kaunapu''', but must say '''ʔá kaunu nà pà''' (I have a coat)

| |

| | |

| As I said above, '''gaza''' always comes with one noun. If it comes with an adjective, then that adjective can be considered a noun (well this is one way to look at it)

| |

| | |

| Also note that when the noun is a noun as opposed to an adjective, ??? , it is always indefinite.

| |

| | |

| '''pona''' = cold (an adjective), '''ponan''' = coldness (a noun)

| |

| | |

| '''ʔá ponan''' = "it is cold"

| |

| | |

| '''ʔá pona paye''' meaning "I feel cold" (word for word ... "there is coldness to me")

| |

| | |

| There is fixed word order : it is always '''gaza''' followed by the noun or NP.

| |

| | |

| The three irregular forms have their own negative marker. '''ya''' is stuck on to the end of the copula.

| |

| | |

| '''ʔaya ponan''' = "it is not cold"

| |

| | |

| Note that the word '''ʔaya''' (there is not) and '''ʔaiya''' (there was not) are very close to each other phonetically. However the middle part of the second word takes twice as long as the middle part in the first word : they are phonetically quite distinct.

| |

| | |

| The particles '''lói''' (probably) and '''màs''' (maybe) normally, come before the verb that they qualify. However the 3 irregular forms of '''gaza''' really like to come clause initially. Hence '''lói''' and '''màs''' immediately follow the verb.

| |

| | |

| '''ʔáu lói ponan''' = It will probably be cold

| |

| | |

| Also the evidentials are affixed to the wild forms, just as normal.

| |

| | |

| '''ʔaunya lói pona''' = They say it will probably not be cold

| |

| | |

| '''ʔaunya.foi lói pona''' = Do they say it will probably not be cold ?

| |

| | |

| === geu ===

| |

| | |

| '''gèu''' is an adjective if it comes immediately after the copula<sup>*</sup> '''sàu'''. For example '''báu rì gèu''' => The/a man was green. (if you wanted to put a substantive after '''sàu''', you would stick '''aja''' "one" in front of it).

| |

| | |

| '''gèu''' is also an adjective if it comes immediately after a noun i.e. '''báu gèu dí''' => This green man

| |

| | |

| In other positions '''gèu''' represents a substansive noun<sup>**</sup>.

| |

| | |

| <sup>*</sup>'''gèu''' is a qualitative noun if it comes immediately after the copula of existence '''gaza'''. For example '''ʔá pona''' => It is cold ... or ... '''ʔá pona paʔe''' => I am cold

| |

| | |

| <sup>**</sup>Well actually in one other position '''géu''' represents a qualitative noun ... after the "copula of existence" (just to make things complicated)

| |

| Now how can we tell if the unmodified '''gèu''' is representing an adjective or a substansive noun. Well we can tell by its position with respect to other elements in the clause.

| |

| | |

| ------

| |

| | |

| [[Image:TW_96.png]]

| |

| | |

| And above we see one more possibility. In the above two examples you can get to the "G" form from the "A" form by a regular process. With '''mapa'''/'''mapau''' this is not possible. So it appears that this word has two base forms ("A" and "G") and this word would have two entries in a dictionary.

| |

| | |

| === From NOTEPAD ===

| |

| | |

| LIMBAWA ... SHIT

| |

| | |

| We have two words meaning "one" (maybe also "two")

| |

| | |

| ABA = one. WEBA ... Once. KIBA .... Unique

| |

| | |

| HEU ... One. KIHEU ... Lonely. WEHEU ... Alone

| |

| | |

| WEHE ... First

| |

| | |

| All nondaua are either nouns, verbs, or adjectives.

| |

| | |

| BARON top houseN ... They say I am on top of the house

| |

| BORIS vicinity doorN ... I saw her near the door

| |

| MAS BIRU game ... Maybe you will be at the game

| |

| MO BIRU game ... You will not be at the game

| |

| | |

| BREAK can just happen be volitional be accidental

| |

| | |

| Find word for ... protagonist, modifier, wild irregular, tame regular, noun, verb, adjective, pronoun, proof

| |

| | |

| KYU ... time

| |

| KWI ... when ??

| |

| KYUDHI … now

| |

| | |

| ==To give and to receive ... kyé and bwò==

| |

| | |

| '''kyé''' means to give and '''bwò''' means to receive or get.

| |

| | |

| -----

| |

| Normal usage

| |

| -----

| |

| | |

| 1) '''jonos<sub>A</sub> kyori jeneye toili<sub>O</sub>''' = John gave a book to Jane "or" John gave Jane a book

| |

| | |

| Linguistic jargon ... In the Western linguistic tradition, Jane is called "the indirect object"(IO). Quite an unfortunate term I think as it is human 99% of the time, hence hardly what you would normally call an object.

| |

| | |

| 2) '''jene<sub>A</sub> bwori toili<sub>O</sub>''' ('''jonovi''') = Jane got a book (from John)

| |

| | |

| O.K. the above is the usage normal usage of '''kyé''' and '''bwò'''. They sort of describe the same action but from two different perspectives.

| |

| | |

| -----

| |

| Causative construction

| |

| -----

| |

| | |

| You can replace the '''cwidau''' with a '''gomua''' in 1) and you get a causative construction.

| |

| | |

| '''kyari jonoye dono''' = I made john walk

| |

| | |

| or you can alternatively use the form '''kyari jono dono''' (in which case '''jono dono''' is considered a '''gomuaza''')

| |

| | |

| '''kyari jono<sup>*</sup> timpa jene''' = I made John hit Jane ... (in which case '''jono dono jene''' is considered a '''gomuaza''')

| |

| | |

| '''jonos kyori pà solbe moze''' = John made me drink the water

| |

| | |

| <sup>*</sup>'''béu''' tries and drops all arguments that can be known without being specified. Now in the above example '''timpa''' is a transitive verb and usually has an A argument and an O argument. In the above example, if '''jene''' was dropped from the '''semo''' (but of course understood from context), then we could have a form '''kyari jonoye timpa'''

| |

| | |

| -----

| |

| Passive construction

| |

| -----

| |

| | |

| 3) '''jonos<sub>A</sub> timpori jene<sub>O</sub>''' = John hit Jane

| |

| | |

| 4) '''jene<sub>S</sub> bwori timpa''' ('''jonovi''') = Jane was hit ... '''jene<sub>S</sub> bwori jono timpa'''

| |

| | |

| 4) is the passive equivalent of 3) ... used when the A argument is unknown or unimportant.

| |

|

| |

|

| | [[Image:TW_146.png]], |

|

| |

|

| | In fact these pronouns are usually dropped when possible, so it might be better to translate the above as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc. |

|

| |

|

| | Below the form of the '''béu''' pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the S or O argument. When they are used as S arguments it might be better to translate these pronouns as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc. |

|

| |

|

| | {| border=1 |

| | |align=center| me |

| | |align=center| '''pà''' |

| | |align=center| us |

| | |align=center| '''yùa''' |

| | |- |

| | |align=center| |

| | |align=center| |

| | |align=center| us |

| | |align=center| '''wìa''' |

| | |- |

| | |align=center| you |

| | |align=center| '''gì''' |

| | |align=center| you (plural) |

| | |align=center| '''jè''' |

| | |- |

| | |align=center| him, her |

| | |align=center| '''ò''' |

| | |align=center| them |

| | |align=center| '''ù''' |

| | |- |

| | |align=center| it |

| | |align=center| '''ʃì''' |

| | |align=center| them |

| | |align=center| '''ʃì''' |

| | |} |

|

| |

|

| You can replace the '''cwidau''' with a '''gomua''' in 2) and you get a passive construction.

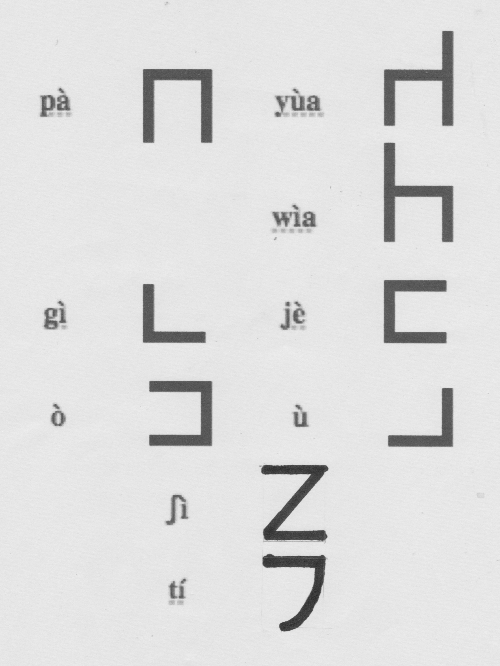

| | The above table is for S and O arguments, it fact we have another pronoun but this one only occurs as an O argument. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves we use '''tí''' to represent the O argument. |

|

| |

|

| '''jene bwori dono''' = Jane was made to walk ????? | | Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in '''béu''' we do not say '''*pás pà timpari''', but '''pás tí timpari'''. |

|

| |

|

| bwò a verb that is intransitive=>a passive causative ??

| | [[Image:TW_162.png]] |

|

| |

|

| '''bwari dono''' = I was made to walk .... this is called a "causative construction" in linguistic jargon.

| | The table above shows the shorthand form for these non-ergative pronouns. |

|

| |

|

| ('''pás''') bwari solbe moze''' ('''jonovi''') = I was made to drink the water (by John)

| | '''tí''' does not have to immediately<sup>*</sup> follow the ergative pronoun but it usually does. There is a recognised way to write the ergative pronoun plus the reflexive particle (i.e. we have one symbol to represent two words). These are shown below. |

|

| |

|

| '''moze bwori solbe''' ('''jenevi''') = The water was drunk (by Jane)

| | [[Image:TW_163.png]] |

|

| |

|

| Called the passive construction in linguistic jargon ... It is used when the A argument is unknown or unimportant.

| | LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in '''béu''' only one. |

|

| |

|

| -----------

| | Pronouns can just be set down beside each other if they both make up the same argument in a clause. Unlike normal nouns which must have '''é''' ( "and" ) between them and any other component. |

|

| |

|

| '''flompe''' is an intransitive verb

| | <sup>*</sup>It is a rule that '''tí''' must follow the A argument. |

| | |

| '''kyé jene flompe''' = to make Jane trip

| |

| | |

| '''kyé jono kyé jene flompe''' = to make John to make Jane trip = to make John trip Jane

| |

| | |

| ==== BIA ......... a copula to much====

| |

| | |

| Ah well ... three copula's are just too many

| |

| | |

| '''bià''' means "to be at"

| |

| | |

| For example '''polo bori london''' = Paul was in London

| |

| | |

| '''polo borta london''' = Paul has been to London

| |

| | |

| '''auto bora lence''' = The car is in the street.

| |

| | |

| '''pele boru nambo''' = Paula will be at home

| |

| | |

| '''bià''' is the rarest of the copulas and has no irregular forms.

| |

| | |

| It is often supplanted by '''sàu''' ... but if this happens a locative particle must be suffixed to the noun (the noun after the copula). For example ;- | |

| | |

| '''polo rì london.pi''' = Paul was in London

| |

| | |

| '''auto (rà) lence.la''' = The car was in the street (literally "on the street")

| |

| | |

| '''pele mò rù namboʔe''' = Paula will not be at home

| |

| | |

| '''béu''' shows the imperfective aspect by prefixing the verb with the particle '''bai''' (see the section on Serial Verb Construction, to find out the origin of this particle)

| |

| | |

| ==== ... '''-kun''' or '''kun''' or '''kunta'''====

| |

| | |

| Affixed to '''gamba''' only.

| |

| | |

| I passed my exams by cheating

| |

| | |

| ==Positive and negative==

| |

| | |

| Above we have used '''-ya''' to generate a negative meaning. This form is used in two other situations to give a negative meaning. In '''aiya''' meaning "no" and in '''kya''' meaning "don't". However there is also 2 situations where '''-ya''' or '''-ia''' have a positive meaning ... in '''fanfia''' (as oppopsed to '''fanfua''') and in the verbal aspect '''-y'''

| |

| | |

| in '''kunjua''' (as opposed to '''kunja''' and in '''umutu''' as opposed to '''mutu'''. This is just the way things are.

| |

| | |

| Said by the philosopher Kantu Banpoʃi, necessary to balance out the ying and yang elements for every minute of the day. However there is another school of thought that says that that is a load of balls and that Kantu Banpoʃi had his head up his own arse.

| |

| | |

| ==== ... '''-dis''' or '''dis''' or '''dista'''====

| |

| | |

| Affixed to '''gamba''' only.

| |

| | |

| I passed my exams without cheating

| |

| Two consonants can appear together at the beginning and middle of a word. The various combinations that are allowed at these two positions are stated later (see '''juzmi'''). Only two consonants are allowed word finally. These are '''n''' and '''s'''.

| |

| | |

| The vowels '''ia''' and '''ua''' can only occur in the final syllable of a word. If a suffix is added, making either '''ia''' or '''ua''' occur in a non-word-final syllable, then they must change to '''ya''' and '''wa''' respectively. However these changes can occur only in certain circumstances, depending on the consonant to the left of the '''y''' or '''w''' (refer to the table in the '''juzmia @aba''' section to see what combinations are acceptable). If the change to '''ya''' or '''wa''' is not allowed, then they both change to a simple '''a'''.

| |

| | |

| ----------

| |

| | |

| If the "modification" is something solid (something you can touch) then the form '''gwomo''' would be used. It is actually hard to draw the line between when '''gwoma''' should be used, and when '''gwomo''' should be used. But the linguistic usage falls just to the '''gwoma''' side of the line. Hence we talk about the '''béu''' verb having 9 '''gwoma''' instead of 9 '''gwomo'''.

| |

| | |

| ----------

| |

| | |

| Word structure "nandau"

| |

| | |

| All '''nandau''' are what are called "content words"⁕ (LINGUISTIC JARGON). They are words like "house', or "run" or "beautiful" that have a definite meaning embedded in themselves.

| |

| | |

| -----------

| |

| | |

| Each '''pyabu''' is defined by 3 '''juzmia'''.

| |

| | |

| '''juzmi''' can be translated as "gesture", "a definite movement given a meaning by socially agreed convention", it also is used for the three parts that define a '''pyabu'''.

| |

| | |

| The three parts are '''juzmi @aba''' (the first gesture), '''juzmi @iga''' (the second gesture) and '''juzmi @oda''' (the third gesture).

| |

| | |

| The rule for determining what is a '''nandau''' and what is not (and by definition "what is not" => '''yadau'''), is that there must be one, and ONLY one '''jwavo''' in the three gestures.

| |

| | |

| '''jwavo''' = "molecule made from more than one element" or "consonant cluster" or "diphthong"

| |

| | |

| ⁕A small number of '''yadau''' are also "content words". Invariable they are very common words. For example '''dunu''' "brown" or '''hiaᴴ''' "red".

| |

| | |

| -----------

| |

| | |

| ⁕⁕⁕It is thought that when multiplication tables were invented, a name for each "entry" was sought. The adoption of '''pyabu''' came about thru analogy to a fishing net (multiplication tables are called "multiplication nets" by the way). The word later spread to 1D systems (i.e. items on a list) and to 3D systems (well the '''nandauli''' is one example)

| |

| | |

| ⁕⁕⁕⁕By the way '''kyamo''' = "molecule made from only one element" or "geminate" or "long vowel" (where long vowels contrast with short vowels to produce minimal pairs)

| |

| | |

| .... the first element "juzmia @aba"

| |

| | |

| There are 37 '''juzmia @aba'''. Some of them are "kolta" (consonants in this case) and some of them are '''jwavo'''(meaning consonant clusters in this case). All the '''juzmia @aba''' are "complex sounds"(consonant or consonant clusters).

| |

| | |

| -------------

| |

| | |

| .... the second element "juzmia @iga"

| |

| | |

| There are 9 '''juzmia @iga'''. Some of them are '''kolta''' (vowels in this case) and some of them are '''jwavo''' (diphthongs in this case). All '''juzmia @iga''' are "simple sounds"(vowels or diphthongs).

| |

| | |

| The '''juzmia @iga''' order is '''e, eu, u, au, a, ai, i, oi, o'''

| |

| | |

| .... the third element "juzmia @oda"

| |

| | |

| There are 58 '''juzmia @oda'''. Some of them are "single sounds" (consonants) and some of them are '''jwavo''' (consonant clusters in this case). All the '''juzmia @oda''' are "complex sounds"(consonant or consonant clusters).

| |

| | |

| ----------------

| |

| | |

| Most '''yadau''' are what are called "particles" in linguistics. These are the short words such as "the", "to", "because" that impart meaning to the '''nandaua''' around them, or specify the relation between two '''nandaua''', or add a certain nuance/meaning to the whole utterance.

| |

| | |

| Examples of '''yadau''' are '''foi''' that is cliticized to the end of the first word of a sentence (thereby turning the sentence into a question). And '''mo''' which goes directly in front of a verb and negates the whole utterance. All the pronouns are also '''yadaua'''. All affixes⁕ also.

| |

| | |

| All words that are not a '''nandau''' are either ''' yadau''' or '''yauyadau'''. '''yadau''' are mono-syllabic and possess either a high tone or a low tone. '''yauyadau''' are poly-syllabic and have neutral tone.

| |

| | |

| ⁕In '''béu''' an affix is called a "part yadau" (as opposed to all the non-affixes which are called "whole yadau")

| |

| | |

| ---------------

| |

| | |

| The '''juzmia @oda''' order is '''l@, lm ... ln, lh, @, m ... n, h, n@, ny ... mw, nh, s@, zm ... zn, sh'''

| |

| | |

| ----------------

| |

| | |

| If you look in the '''nandauli'''⁕⁕ (dictionary) you will get a form such as '''hend-'''. This is what is also called a '''pyabu'''.

| |

| | |

| Actually the original meaning of '''pyabu'''⁕⁕⁕ was "knot". It's meaning then spread to "entry" (in a ledger for example) or "item" (in a list for example). Then it spread to such forms as '''hend-'''. If you add a tail to a '''pyabu''' you get a '''nandau'''. For example '''henda''' = "to wear" is a '''nandau''', or '''hendo''' = "an item of clothing'" is also a '''nandau'''

| |

| | |

| -------------------

| |

| | |

| ==A list of the 12 colours==

| |

|

| |

|

| | The possessive form of these pronouns |

|

| |

|

| {| border=1 | | {| border=1 |

| |align=center| black | | |align=center| my |

| |align=center| '''àu''' | | |align=center| '''pàn''' |

| |-

| | |align=center| our |

| |align=center| white

| | |align=center| '''yùan''' |

| |align=center| '''ái'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| red

| |

| |align=center| '''hìa'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| green | |

| |align=center| '''gèu''' | |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| yellow | | |align=center| |

| |align=center| '''kiʔo''' | | |align=center| |

| | |align=center| our |

| | |align=center| '''wìan''' |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| light blue | | |align=center| your |

| |align=center| '''nela''' | | |align=center| '''gìn''' |

| | |align=center| your (plural) |

| | |align=center| '''jèn''' |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| dark blue | | |align=center| his, her |

| |align=center| '''nelau''' | | |align=center| '''òn''' |

| | |align=center| their |

| | |align=center| '''ùn''' |

| |- | | |- |

| |align=center| orange | | |align=center| its |

| |align=center| '''suna''' | | |align=center| '''ʃìn''' |

| |-

| | |align=center| their |

| |align=center| brown

| | |align=center| '''ʃìn''' |

| |align=center| '''dunu'''

| | |} |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| pink

| |

| |align=center| '''celai'''

| |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| purple | |

| |align=center| '''helau''' | |

| |-

| |

| |align=center| grey

| |

| |align=center| '''lozo'''

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| ==..... Three infixes for Verb => Verb==

| |

| | |

| '''béu''' has a three process for generating new verbs from existing verbs.

| |

| These three processes can be done to any verb.

| |

| | |

| .... -el-

| |

| | |

| If you split a verb and insert '''el''' between the final vowel (of the '''gamba''') and the rest of the word, you give the added meaning of "to begin", "inception" or "to start off". For example ;-

| |

| | |

| '''sàu''' = to be

| |

| | |

| '''selau''' = to become

| |

| | |

| '''bìa''' = to be at

| |

| | |

| '''belia''' = to arrive at

| |

| | |

| '''doika''' = to walk

| |

| | |

| '''doikela''' = to start to walk

| |

| | |

| '''logo doikorwi''' = Roger used to walk ...

| |

| | |

| '''logo doikelorwi''' = Roger used to start walking ...

| |

| | |

| '''gazelari''' = I was born

| |

| | |

| '''à rì kiʔo''' = it was yellow ... remember that '''rì''' is an irregular form. The regular form would be '''*sori'''.

| |

| | |

| '''à lori kiʔo''' = it became yellow ... '''selau''' is irregular. If it were regular we would have the form '''*à selori ki@o'''

| |

| | |

| So there are thee irregular verbs in '''béu''' (well if you count '''selau''' as a different word from '''sau''') ... '''sàu''', '''bìa''' and '''selau'''.

| |

| | |

| .... -ow-

| |

| | |

| If you split a verb and insert '''ow''' between the final vowel of and the rest of the word, you get the meaning that you are making somebody else do the verb. For example ;-

| |

| | |

| '''ò timpiri''' = you hit him

| |

| | |

| '''(pás) gís ò timpowari''' = I made you hit him ???

| |

| | |

| A '''gamba''' form exists for this construction also. For example;-

| |

| | |

| '''doikowo''' = to make (somebody) walk

| |

| | |

| '''gasowa''' has the special meaning "to give birth" and doesn't mean "to create".

| |

| | |

| .... -ay-

| |

| | |

| If you split a verb and insert '''ay''' between the final vowel of and the rest of the word, you get the meaning that the verb is being attempted. For example ;-

| |

| | |

| '''selbaru à''' = I will drink it

| |

| | |

| '''selbayaru à''' = I will try and drink it

| |

| | |

| -----

| |

| By the way, in '''béu''' to get a progressive meaning we use a Serial Verb Construction (SVC) ... '''báu bài kludora''' = The man is writing ... '''báu''' = man, '''bìa''' = to stay

| |

| | |

| By the way, in '''béu''' to get a passive meaning we use a Serial Verb Construction (SVC) ... '''toili gài kludorta''' = The book has been written ... '''toili''' = book, '''gùa''' = to undergo .... ('''toili gài kludorta''' is this right ?)

| |

|

| |

|

| Actually we can make a really biy SVC and have '''toili bài gài kludora''' = The book is being written.

| | And we also have '''tín''' which is used if the possessor is the same as the subject of the clause. |

|

| |

|

| ==Index== | | ==Index== |

|

| |

|

| {{Béu Index}} | | {{Béu Index}} |