Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective: Difference between revisions

| Line 1,629: | Line 1,629: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| yon || person-{{small|NOM}} || book-{{small|ACC}} || write-{{small|ACC}} || {{small|CI-NOM}} || well || known || {{small|COP}} | | yon || person-{{small|NOM}} || book-{{small|ACC}} || write-{{small|ACC}} || {{small|CI-NOM}} || well || known || {{small|COP}} | ||

|} | |}=> It is well known that that person wrote a book | ||

.. | .. | ||

Revision as of 07:17, 8 September 2017

..... Short Verbs

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an R-form is to delete the final vowel from the maŋga. However this is only applicable for multi-syllable words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different. For monosyllabic verbs the R-form suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive.

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ...

Many béu speakers pronounce a glottal stop between the two parts, especially if they are speaking forcefully.

In my transcription a dot is inserted between the base and the suffixes. In the béu writing system the two vowels are simple written alongside.

..

..

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the R-form.

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ...

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the R-form.

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ... ʔawir = you take ...

..

However 37 monosyllabic maŋga are exceptions : they pattern exactly the same as poly-syballic verbs.

..

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to store | ||

| yáu = to have | |||

| jò = to go | jwòi = to to pass through, undergo, to bear, to endure, to stand | ||

| féu = to exit | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

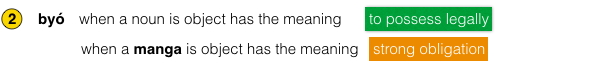

| bái = to rise | byó = to own | blèu = to hold | bwí = to see |

| gàu = to do | glù = to know | gwói = to pass by | |

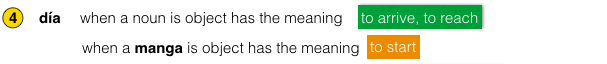

| día = to arrive / reach | dwài = to pursue | ||

| lài = to become | |||

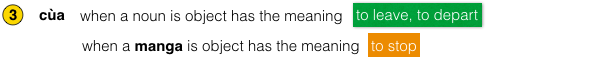

| cùa = to leave / depart | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slài = to change | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kàu = to fall | kyò = to use | klói = to like | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyá = to fly | plèu = to follow | |

| té = to come | twá = to meet | ||

| wè = to think | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to learn |

..

For example ... pòr nambo = he/she enters the house ... not *poyor nambo

Note ... té "come" and jò "go" are Ø. However when the place being "gone to" or the place being "came from" are dían "here" or dèn "there" ... no dative mark (-n) is appended. Probably best to analyse this as a quirk of dían/dèn rather than té/jò being ambitransitive in any way.

The above are also among the most common verbs as well. If you are serious about learning béu you should try and memorize them as soon as possible.

..

..... Adjectives => Verbs

..

Some concepts that are coded as adjectives in English, are coded as verbs in béu. Usually they are body internal processes or states. So joining "to sleep", "to love", "to hate" (which are stative verbs in English) we have concepts like "to be angry", "to be jealous", "to be healthy" encoded as verbs in their base state.

[Note ... most of these are mental states]

Now in béu all multi-syllable adjectives become verbs simply by adding the verb train to them. For example ...

coga = wide

coguran komwe = it seems they have widened the road

However ... to make the corresponding maŋga you must add the suffix do. For example ...

cogako = to widen

For the few mono-syllabic adjectives that exist, this suffix must be present all the time. For example ...

àu = black

auko = to blacken

aukuran komwe = it seems they have blackened the road

Notice that these derived verbs are all transitive. To have the intransitive sense, you must use the verb tezau "become" along with the adjective.

..

..... 4 adjectives => verbs via derivation

..

| bòi* | good |

| kéu* | bad |

| fái | rich ** |

| pàu | bland |

..

The above adjectives have an "s" affixed and change into verbs. However the meanings derived are a bit quirky.

..

| bòis*** | to be healthy/health | boizora | she is healthy |

| kéus | to be sick/illness | keuzora | he is ill |

| fáis | to be attentive/to like/attention | faizora | she is interested |

| pàus | to be bored/boredom | pauzora | he is bored |

..

* The adverb derived from these words are slightly irregular. Instead of boiwe it is bowe. People often shout this when impressed with some athletic feat or sentiment voiced ... bowe bowe (well done) => bravo bravo Also instead of keuwe we have kewe. People often shout kewe kewe kewe if they are unimpressed with some athletic feat or disagree with a sentiment expressed. Equivalent to "Booo Boo".

**"rich" in its non-monetary sense. If applied to food it means many flavours and/or textures. If applied to music it means there is polyphony. If applied to physical design it means baroque.

***This appears in its subjunctive form as an expression often used when people are parting for what is expected to be some time. boiʒis => "may you be well".

..

... 10 adjectives which never appear as verbs

..

| sài | young |

| gáu | old (of a living thing) |

| jini | clever, smart |

| tumu | stupid, thick |

| wenfo | new |

| yompe | old, former, previous |

| dìa | east, dawn, sunrise |

| cúa | west, dusk, sundown |

| bene | right, positive |

| komo | left, negative |

..

Of course you can always use a periphrastic expression if you wanted. For example ...

sàr tumu = I am stupid

tezar tumu = I become stupid

gàr tumu = I make (someone) stupid

Some of the above can be considered more nouns than verbs. For example ... dìa and cúa.

These two are of interest for another reason ... dìa combines with día .. "to arrive" to make the word ... diadia .. "to happen". Also cúa combines with cùa .. "to depart" to make the word ... cuacua .. "to fade away".

Note that although the components going into these words have exactly opposite meanings, the compound words do not.

diadia appears in quite common expressions. For example ...

nén r diadila = "what's happening"

nén diadori = "what happened"

..

... 16 adjectives => verbs with zero derivation

..

| boʒi | better | kegu | worse |

| faizai | richer | paugau | blander |

| maze | open | nago | closed |

| saco | fast | gade | slow |

| fazeu | empty | pagoi | full |

| hauʔe | beautiful | ʔaiho | ugly |

| ailia | neat | aulua | untidy |

| coga | wide | deza | narrow |

Note that the first two are irregular comparatives. The standard method for forming the comparative and superlative is ... ái = white : aige = whiter : aimo = whitest. ..

These adjectives directly become verbs. For example ...

| bozor | he improves | kegor | he worsens | boʒido | to improve | kegudo | to made worse |

| faizor | she develops | paugado | she runs down | faizado | to enrich/develope | paugado | to run down |

But notice that the infinitive form of this derived verb has the affix "do".

..

... 36 adjectives => verbs with derivation

..

| ái | white | àu | black |

| hái | high | ʔàu | low |

| guboi | deep | sikeu | shallow |

| seltia | bright | goljua | dim |

| taiti | tight | jauju | loose |

| jutu | big | tiji | small |

| felgi | hot | polzu | cold |

| naike | sharp | maubo | blunt |

| nucoi | wet | mideu | dry |

| wobua | heavy | yekia | light |

| pujia | thin | fitua | thick |

| yubau | strong | wikai | weak |

| fuje | soft | pito | hard |

| gelbu | rough | solki | smooth |

| ʔoica | clear | heuda | hazy |

| selce | sparce | goldo | dense |

| cadai | clean | dacau | dirty |

| igwa | elegant | uʒya | crude |

These adjectives do not become verbs directly, even as finite verbs (helgo form) they have the affix do.

| aikor | he whitens | aukor | he blackens | aiko | to whiten | auko | to blacken |

| haikor | she raises/rises | ʔaukor | she lowers | haiko | to raise | ʔauko | to lower |

So why do some verbs have ko in their finite form and others not. Well monosyllable adjectives always take ko. As for the rest, the ones that appear often as verbs, drop the ko in their finite form.

Notice that for multi syllable adjectives ending in a diphthong, the final vowel s dropped before appending ko.

..

However not quite all antonyms fall into the above pattern. For example ...

loŋga = tall, tìa = short

wazbia = far : wazbua or mùa = near : wazbi = distance : wazbai = about 3,680 mtr

..

..... Family

..

Usually the words below are used to address members of your family (names are not usually used). All the words below have a special vocative case ... formed by prefixing a.

amama ... klogau dá = Mum, where are my shoes ?

..

There are 14 primary family relationships ...

..

| mother | mama |

| son | yaya |

| daughter | jaja |

| grand-daughter | fafa |

| father | baba |

| older sister | gaga |

| older brother | dada |

| grand-mother | caca |

| female cousin | saza |

| younger sister | kaka |

| grandson | papa |

| younger brother | tata |

| grandfather | wawa |

| male cousin | nana |

..

Below are 8 secondary family relationships.

..

| daba | uncle | the older brother of your father |

| taba | uncle | the younger brother of your father |

| gaba | aunt | the older sister of your father |

| kaba | aunt | the younger sister of your father |

| dama | uncle | the older brother of your mother |

| tama | uncle | the younger brother of your mother |

| gama | aunt | the older sister of your mother |

| kama | aunt | the younger sister of your mother |

..

And below are a further 8 secondary family relationships.

..

| yaja | offspring |

| maba | parents |

| cawa | grandparents |

| data | brothers |

| gaka | sisters |

| daga | elder syblings |

| taka | younger syblings |

| fapa | grandchildren |

..

It is worth mentioning that theae 30 words are all automatically taken as related to the speaker if no other possessor is mentioned. For example ...

..

..... Six causative constructions

..

"John made Jane drink the water" is an English causative construction ... [Note on terminology ... we call "John" the "causer" and "Jane" the "causee"]

..

In a similar manner to English ... béu uses gàu (meaning "to do" or "to make") as the neutral term for coding causation. For example ...

(a) jonos gore solbe moze jenen = John made Jane drink water (earlier today)

..

| jono- | g-o-r-e | solbe | moze | jene-n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John-ERG | "do"-3SG-IND-PST | drink.INF | water | Jane-DAT |

..

Note that the causee gets the dative affix. Also note that maŋga immediately follows gàu, the maŋga object immediately follows maŋga. The causee can come anywhere but the string gore solbe moze can not be broken. There are 3 possible places where jenen can appear.

And another example ...

jonos gore náu onyo waulon jenen = John made Jane give the bone to a dog (earlier today)

Notice that we have two datives in this construction. The string gore náu onyo waulon can not be broken.

..

This construction implies that the causer was present when the event happened. We call it a "direct" causative construction.

There is another causative construction which doesn't imply the causer was present when the event took place. In fact it implies that the causer took some action which at a later time made the causee do what they did. The two actions very probably being linked by some sort societal connection (via other people).

(b) jonos gore gò jenes solbore moze = John had Jane drink water

The clause after gò ( i.e. jenes solbore moze ) has free word order.

The indirect causative construction is iconic ... separating the two verbs with gò reflects the separation of the two events ... both timewise and otherwise (i.e. there could have been a chain of protagonists involved).

..

There are 4 other causitive constructions in béu ... gàu is neutral as to how the causee views the action they are made to do.

If the causee is reluctant ... we use tumai "to squeeze" or "to press" instead of gáu.

If the causee is eager ... we use náu "to give" instead of gáu. For example ...

..

(c) jonos tumore solbe moze jenen = "John made Jane drink water" or "John forced Jane to drink water (earlier today)"

(d) jonos tumori gò jenes solbore moze = "John had Jane drink water" or "John arranged that Jane had to drink the water" ... (the drinking occurred earlier today, the causing of the drinking ... yesterday or before)

(e) jonos nore solbe moze jenen = "John let Jane drink the water (earlier today)"

(f) jonos nori gò jenes solbore moze = "John allowed Jane to drink water" or "John arranged for Jane to be able to drink water" ... (the drinking occurred earlier today, the arranging of the drinking ... yesterday or before)

..

Notice that in (a), (c) and (e) the maŋga must occur immediately after gàu, tumai or náu. This is the same as the French, Italian or Spanish causative constuctions. Here is a French example ...

..

==> I will make Jean eat the cakesje ferai manger les gâteaux à Jean 1sgA make+fut+1sg eat+inf the cakes prep Jean

..

(a), (c) and (e) have what is called a compound causative verb. (i.e. one clause) ... (b), (d) and (f) are what are called periphrastic causative constructions. (i.e. two clauses)

..

It is possible for the indirect paraphrastic construction to give the embedded clause an impersonal form. For example ...

jonos gori gò solb-re moze = "John had the water drunk" or "John arranged for someone to drink the water" ................. [notice : no causee]

..

..

In the above table, it can be seen that there are 6 causative constructions. There are 3 degrees of "volition" (the willingness of the causee) and 2 degrees of "directness" (did the causer act directly on the causee or through intermidiaries).

..

It is possibly to chain causative constructions together. For example ...

..

jonos flòn jodoi = John feeds the animals.

g-r gò jonos flòn jodoi = John is made to feed the animals.

(nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = they make John feed the animals.

gàu gò (nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = make them make John feed the animals.

by-r gàu gò (nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = it is necessary to make them make John feed the animals.

(gís) byír gàu gò (nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = you must make them make John feed the animals.

..

And 2 of these 3 causative verbs can be given impersonal forms ....

jenen g-ryə doika or g-ryə doika jenen = "Jane has been made to walk" or "somebody has make Jane walk

jenen tum-ryə doika or tum-ryə doika jenen = "Jane has been forced to walk" or "somebody has forced Jane to walk

Now náu "to give" is a strange word in that it never takes an impersonal form (see the section above). Instead the word mài "to receive/get" is used.

jene moryə doika = "Jane has been allowed to walk" ... [ as opposed to *jenen n-ryə doika ]

We will learn more about mài Ch 4.6 and Ch 4.7.

..

Another verb that we can mention here is penau meaning "to persuade, coax, convince, bring around, influence, sway"

penarua jene jonowo = "I intend to persuade Jane about John" = "I intend to bring Jane around to my way of thinking with respect to John"

(pás) penare jono jò nambon = "I got John to go home" = "I persuaded John to go home" .... [Note ... the maŋga does not immediately follow for penau ]

(pás) penare jono gò baba yor jò nambon = "I persuaded John that father should go home"

Also penau says nothing about the success of the action ... unlike the 3 other verbs we have considered where success is assumed.

..

..... Two quotative verbs

..

béu has two quotative verbs ... swé and aika. What I mean by the term "quotative verb"is a verb which must* be accompanied by a string of direct speach ["sods" from now on]

swé = "say" and aika = ask .... ( that is to ask for information, to request something (to ask for) has a completely different root ... namely tama )

I guess it is intransitive because the speaker never takes the ergative ending "s". The spoken to (if mentioned) takes the dative ending "n".

[Some people would like to argue as to whether "sods" = an object or whether "sods" = a complement clause. I think this is not worth arguing about. It is similar to arguing about how many angels can stand on the end of a needle. ]

There is an ordering restrictions for a clause formed around a quotative verb ... the "sods" must appear adjacent to swé or aika. It doesn't matter which comes first but they must be adjacent ... normally both elements are pronounced in the same intonation contour. A second restriction is that there must be a pause at the other end of the "sods" ... the opposite end from the quotative verb. For example ...

John said "Ai ... go away" => jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo where aiʔdo is an interjection expressing frustration and ojo is quite a rough way to say "go away".

This can also be expressed as aiʔdo ... ojo swori jono or jono ... aiʔdo ... ojo swori or even swori aiʔdo ... ojo ... jono. The first two patterns are the most common followed by the third pattern and the fourth a distant last. Notice that the "sods" that I chose for demonstration purposes entails an internal pause.

If we introduced a dative element ...

John said to Jane "Ai ... go away" => jono jenen swori aiʔdo ... ojo

The above would be the most common ordering of constituents ... but again quite a bit of freedom with respect to word ordering.

The "sods" can be quite lengthy ... 2 or 3 or 4 clauses and follows as near as possible the speach pattern of the original speaker.

The béu orthography is a bit quirky when it comes to quotative verbs. In CH 1.8 we briefly mentioned the deupa. These are actually used to bracket any "sods". Also it is common to drop the actual quotative verb. (well after the time setting of the speach act(s) are revealed anyway). For example ...

The first one is graphically jono [ aiʔdo ... ojo ] ... (for an explanation of the graffic form of the interjection aiʔdo, look back to CH 1.2)

The second one is graphically jono [ bàu nái ]

These would be read as jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo and jono aikori bàu nái (John asked "which man")

But how do we know that swé should be associated with one and aika to the other ? Simple ... if you have a question word within the deupa then you know you should pronounce aika ... if not you pronounce swé. We have encountered these question words already in CH 2.10. There are ten of them but the first two have two forms. Here they are again ...

..

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| láu | "how much/many" |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| dá | where |

| kyú | when |

| sái | why |

| nái | which |

| ʔai? | "solicits a yes/no response" |

| ʔala | which of two |

..

The only time that you hear these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are in the same intonation contour as the verb "aika" in one of its forms.

The only time that you see these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are sandwiched between two deumai.

This is quite a bit different from English where question words have been appropriated to function as relativizers, complementizers and what have you (heads of free relative clauses).

In the above ... when pronouncing words ... swé or aika is inserted where the first bracket appears. It could equally well be that swé or aika is inserted where the second bracket appears. It is deemed to not really matter that much. However in carefull writting the proper position of the quotative verb can be indicated. For example ...

In the above a pause (gap) is visible just above the top deupa. From that it is logical to deduce that swé or aika should be inserted after the "sods". (from the word order and intonation rules given earlier). But most of the time ... when reading out loud ... people do not take much heed to whether the quotative verb is placed over the deupa damau or the deupa dagoi.

In a textblock, which you have a lot of dialogue it is common to colour code the "sods" with respect to the speaker. For example ...

When this happens the deupa has no gold filling. It could be possible to drop the speakers name also once the colour coding scheme is established. This really depends upon how much dialogue is involved. Maybe each speaker would be mentioned again at the start of every textblock ... just to keep the protagonist <=> colour mapping alive in the readers mind.

..

* In the very first sentence of this section I said that "quotative verb"is a verb which must be accompanied by a "sods" ... not quite true. The determiners dí and dè can take the place of a "sods". In these constructions dí refers to a "sods" that will be revealed imminently ... dè refers to a "sods" that was spoken in the past.

If Jane pronounces an opinion about something ... if John had pronounced roughly similar in the past ... it would be fitting to say jono swori dè.

If you are about to replay some utterance by John on a voice file, it would be appropriate to say jono swori dí just before playing the voice file.

..

IMPORTANT ... The only time you hear direct speech is when swé or aika is present in one of its forms.

..

..... Speech verbs

..

We have already briefly touched on serial verb chains. These are in fact the i-form of the verb.

The i-form of swé is often used to give strings of direct speech in conjuction with another verb. Usually this other verb denoted some time of speech event. There are around 50 speech-verbs in béu ... melita "to agree" : noluja "to disagree" : malapa "to equivocate" : : oldo "to order/command" : endo "to introduce/recommend" : enji "to suggest" : ʔuaho "to exclaim" : ʔaume "to scream" : uhozo "to exhort/urge" : dauŋgo "to repeat/relay" : diŋkli "to discuss" : dawata "to haver" : daumpa : "to scold/berate" ... etc. etc.

..

uhozo is an S-verb meaning "to urge", "to exhort".

So you could use uhozo as the main verb in the clause and then can add the sods marked with swə ...

uhozora jenes jono ... gì r boimos swə => Jane is cheering on John shouting "you are the best"

..

| uhoz-o-r-a | jene-s | jono | gì | r | boimos | swə |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "exhort"-3SG-IND-PRS | Jane-ERG | John | you | COP | the best | saying |

..

dauŋgo is an S-verb meaning "to repeat, to relay"

tomos dauŋgore jene swə gì r boimos = Thomas repeated Jane saying "you are the best"

..

The i-form of aika is also used fo give "sods". For example ...

daulau is an NS-verb meaning "to joke".

daulori jene jonotu aiki bla bla bla => Jane joked with John asking bla bla bla (well to make this a good example I would have to invent a quite involved scenario, but I hope you get the idea ... even with the ellipses)

..

The use of alki and swə in conjunction with one of the speech act verbs are an important structure in béu grammar and adds to the beauty and functionality of the language.

This structure is really only applicable to speech act verbs. If it was used with a non-speech-act verb it would sound a bit strange to the ear of a béu speaker. For example ...

?jono doikori dunheun swə falaja r NICE sowe = John walked to the civic centre saying "what a beautiful morning"

..

béu maintains a dichotomy between speech-verbs and thought-verbs. Speech-verbs can take a swə/aiki adjunct whereas thought-verbs can take a complement clause introduced by the particle gò in place of an O argument. We will go into this more in the next section.

This dichotomy is not total though. There is some merging between the two constructions.

For example ... ʕelo "to hear" may be considered unique w.r.t. the constructions it can appear in ...

ʕelari jwadoi = I heard some big birds

ʕelari jono = I heard John

ʕelari jono swé bù ʔár jò = I heard John say "I don't want to go" ....... OK I suppose we analyze swé bù ʔár jò as an adjuct similar to swə bù ʔár jò in jono nolujori swə bù ʔár jò "John disagreed saying "I don't want to go"

ʕelari gò jono bù jorua I heard that the jono doesn't intend to go

ʕelari swər bù jarua = I heard it said "I will not go" .............. And we can analyze this as an transitive verb where the object has been dropped.

Also glùn "to inform, to tell" is both a thought-verb and a speech-verb. The informer is in the ergative, the informed the dative. The object can be an object (i.e. the news) or a complement clause (i.e. gò jono bù jorua) or it can simply be missing (when we use glùn as a speech-verb) ... or should we consider that when it is used as a speech-verb that there is an object ... something generic like "the news" but that it can be dropped. Well neither answer is right in itself.

..

..... Thought verbs

..

Everybody carries an (imperfect) model of his environment in his mind and uses this model to plan his actions. The main reason HUMANS have been so successful compared to other animals is that we have a more complete model than ... say ... our primate cousins. The reason that out model is good is that we have LANGUAGE and so get information from our fellows. Probably the building of this MODEL and LANGUAGE were co-developements and could well be reflected in the size of the HUMAN BRAIN over the last few million years. I believe that this MODEL and LANGUAGE are intertwined and hence I don't think it is a good idea to consider either in isolation.

Now usually when we communicate ... we just talk about reality. For example ... JOHN IS TALL. We do not acknowledge the actual more complicated situation ... IN MY WORLD MODEL, JOHN IS TALL.

But sometimes we do .... usually when we are talking about activities related to our mind ... like "thinking", "knowing" ... disseminating knowledge to our fellows "telling", "saying" ... gathering knowledge first hand "seeing", "hearing" ... trying to gather knowlege from our fellows "asking". All these bracketed verbs can take what are called complement clauses. When you see a complement clause you are seeing an admission that what we are talking about is not in fact REALITY, but some MODEL of REALITY. Maybe you could say that it is an admission that we are using META-DATA rather than DATA.

The 4 panels below might illuminate what I am trying to say. What is on the white background is REALITY. What is on a black background is part of a MIND MODEL . The script on an orange background is a speach act appropriate for the situation shown. The top panel is the way that we normally speak ... that is REALITY is presented directly with no referrence to any MIND MODEL.

Now it seems that the majority of languages have at least one way of bracketing off the META-DATA from DATA. English has two types of complement clause (CC from now on) ... one introduced by the complementizer "that" and the other introduced by a question word. These usually take the place usually taken by an O argument. béu has one CC which is introduced by the particle gò. Some of the thought-verbs that can take either a CC or an O argument are listed below ...

petika "to select/choose/pick/decide" : glù "to know" : wè "to be thinking about/consider/ponder" : celba "to remember" : dolka "to forget" : wespila "to understand" : glùn "to inform/tell" : celban "to remind" ... etc. etc.

béu does not have indirect speech as English has ... i.e. John said (that) that was stupid. In béu this would have to be framed as direct speech ... i.e. "this is stupid" said John (notice the change of reference for time and argument). Also ... "John asked whether I wanted to go" would be recast as "John asked "you want to go ?" "

The béu CC is exclusively used for thought-verbs ( IS THERE AN EXCEPTION TO THIS ?? )

..

..... The reciprocal construction

..

The reciprocal particle is bèn

jonos jenes timpur bèn = "John and Jane are hitting each other" = "John and Jane hit one and other"

Note ... lè "and" is not used when two nouns in the ergative case occur adjacent to each other.

The particle also comes after adjectives occasionally. For example ...

jono lè jene r ʔài bèn = John and Jane are the same.

No real reason why it should be added to the above sentence ... except that it is judged to sound good.

ʔáu bèn "to take mutually" is the béu expression meaning ... do the dirty deed, have relations, roger, root, shag, boink, slam the clam, thump thighs, pass the gravy, wet the willy, make the beast with two backs ... make love.

..

..... Numbers

..

The standard set comprises of the numbers from 1 to 172710 (which is 1 to 100012 in base twelve). Every number in the standard set has a unique form.

Five random numbers are given below to demonstrate ...

| oila | = 6 |

| eucaifa | = 7212 |

| odauba | = 50312 |

| odaugaiba | = 54312 |

| oilaugai | = 64012 |

..

And below is how these numbers are written within a body of text.

..

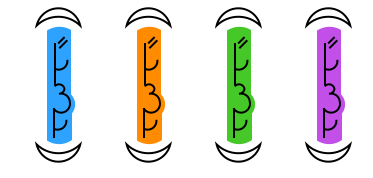

Within a body of text ("textblock" from now on) a number written vertically and is headed up by a special three sided bracket. The only use of this bracket is to indicate a number within a textblock.

Below this bracket, the number is written with a letter representing each digit of the number

Under the bracket the number is written using a letter symbol.

| letter | digit | ..... | letter | digit | ..... | letter | digit | |||

| J | => | 1 | D | => | 5 | K | => | 9 | ||

| F | => | 2 | L | => | 6 | P | => | 10 | ||

| B | => | 3 | C | => | 7 | T | => | 11 | ||

| G | => | 4 | S | => | 8 |

You can see that base 12 is being used. (just for explanatory purposes I will use "T" for 10 and "E" for 11)

More or less the same symbols is used for the number digit as for the letter. They take their initial, medial or final form, depending on whether the are the first, second or third number of the three digit group. táu ʔusʔa is used for inserting zeroes. táu ʔusʔa is never pronounced, it is only a place holder as number magnitude depends on position.

Although there is a unique word for 1727 numbers, it is not necessary to memorize 1727 unique forms. The 1727 numbers are built up from smaller elements. These elements are shown below ...

..

| 10012 = | ajau | 1012 = | ajai | one = | aja |

| 20012 = | ifau | 2012 = | aifai | two = | ifa |

| 30012 = | ubau | 3012 = | ubai | three = | uba |

| 40012 = | egau | 4012 = | egai | four = | ega |

| 50012 = | odau | 5012 = | odai | five = | oda |

| 60012 = | oilau | 6012 = | oilai | six = | oila |

| 70012 = | eucau | 7012 = | eucai | seven = | euca |

| 80012 = | aizau | 8012 = | aizai | eight = | aiza |

| 90012 = | aukau | 9012 = | aukai | nine = | auka |

| T0012 = | yapau | T012 = | yapai | T = | yapa |

| E0012 = | watau | E012 = | watai | E = | wata |

..

To construct a number from the above ...

1) Select which elements you need. For example, for 54312, you will need the elements odau + egai + uba

2) If the element is non-initial, delete the initial vowel of the element => odau + gai + ba ... (note that ya and wa were originally ia and ua ... they should be deleted)

3) Join the elements up => odaugaiba

..

There is a soecial form for 1, 2 and 3 ... aja, ifa and uba, while used for building up larger numbers, are never used by themselves when qualifying animate things. Instead we use ...

..

| ʔà | one |

| hói | two |

| léu | three |

..

ʔà along with its plural form ʔài are also used to code indefiniteness ???

..

Numbers are never written out in full. Always the method given above is used. It is as if in a body of English text you never came across the "seven" but only "7".

..

Note ... If you had a leading zero you would use the word jù. 007 would be jù jù euca (three words). To deal with a telephone number, you would lump the numbers in threes (any leading zero or zeroes by themselves though) and outspeak the numbers. If you were left with a single digit (say 4) it would be pronounced egau. If you were to pronounce it ega, it would of course mean 004. Also you would probably add the particle dù at the end.

..

..... Ordinal numbers

..

With fractions, cardinal numbers and numbers denoting group size, there is the choice of writing 7th or seventh. That is you can either use the symbols given below or you can write out in full ... in this example dega, lega and egan.

..

..

If an ordinal number within a NP specified it is just the bare number inserted in the adjective slot. For example ...

bàu léu = the third man

If the ordinal number appears outside a NP its form is as follows ...

..

| ?à | one | --- | da?a | first | --- | laja | whole | --- | ajan | a unit | --- | ajas | once |

| hói | two | dahoi | second | lifa | a half | ifan | a double | ifas | twice | ||||

| léu | three | daleu | third | luba | a third | uban | a treble | ubas | thrice | ||||

| ega | four | dega | fourth | lega | a quarter | egan | a quartet | egas | four times | ||||

| oda | five | doda | fifth | loda | a fifth | odan | a fivesome | odas | five times | ||||

| oila | six | --- | doila | sixth | --- | loila | a sixth | --- | oilan | a sextet | --- | oilas | six times |

..

Probably a contraction of dà oda ... "place five" ... for example ...

dahoi r jene or jene r dahoi = "second is Jane" or "in second place is Jane" or "Jane is second" or "Jane is in second place"

..

An -n can also be affixed to make it more definite (that is saidau => saidaun) ...

dahoin rò jene or jene r dahoin = "the second one is Jane" or "Jane is the second one"

..

..... Numbers ... (the extended set)

..

So far we have covered the standard set (1 -> 1727). To expand this into "the extended set" we use "magnitude" words. There are seven of these.

..

..

The first column gives the magnitude symbol, the second ... how the symbol is pronounced, the third ... the meaning*, and the last ... the magnifier that the symbol represents.

Two of the magnitude words have been eroded from the original aninal name, 100012 is now represented by wú rather than the original wúa and 1/100012 is now represented by yàn rather than the original yanfa.

.* Yes all the magnitude words double up as animal names. But actually this never causes any problem. If you hear huŋgu huŋgu you know it means "5,159,780,352 Swans" ... there is no ambiguity.

To demonstrate the use of the magnitude words, let's take a long number ... 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559

Which is written as ...

and pronounced as ... aja huŋgu ifaula nàin aizautaiba wú odaija ʔomba odauzaipa yàn oilaubai mulu odaudaika ʔiwetu dù

You can see that the digits are still grouped into bunches of three. Within the triplets, leading zeros can be dropped ... giving doublets or even singletons.

All the magnitude words are spoken out. Notice the final dù. This means "exactly". You usually add this when pronouncing numbers from the extended set.

Now when numbers of the extended set are used to qualify a noun they are placed after that noun with the partitive particle làu between the number and the noun. For example ...

3,05112 elephants = sadu làu uba wú odaija ............ Note ... the singular form of senko always used when quantity is given by this method.

Also if fractions or indeed any non-integer number is used, it must be applied using làu. However non-integer things are likely to be olus and we have already degreed that olus quantifiers are partitive measure phrases.

When you write an extended set number, you must finish the number off with a bracket. (in contrast the final bracket is never used if the number is from the standard set)

Anyway ... the above is only an example. You are unlikely to find something with so big a dynamic range within a textblock.

Below are examples of numbers which you would more typically find in a text block ...

Pronounced uba wú odaija dù and odaija ʔomba odauzai respectively.

(a) uba wú odaija dù is an whole number.

odaija ʔomba odauzai is not a whole number. Notice that the 4 versions of odaija ʔomba odauzai have been given different kinds of final brackets.

(b) This one shows that 51.5812 is an approximation to the actual value. (pronounced daula)

(c) This one shows that 51.5812 has been rounded down. That is .. if A = "actual value", then 51.59 =< A =< 51.58

(d) This one shows that 51.5812 has been rounded up. That is .... if A = "actual value", then 51.58 =< A =< 51.57

(e) This one shows that 51.5812 has been rounded up or down to the nearest digit. That is .... if A = "actual value", then 51.585 =< A =< 51.575

..

dù and daula ( plus ? plus ? plus ?) as well as giving information about the accuracy of the number, also lets the listener know that the speaker has finished.

..

..... Numbers ... (free form + plus mathematical notation)

..

The numbers considered above were all in what is called "block form". That is ... the form they appear as within a body of text. There is also a way to write numbers when they are not inside a text block. That would happen on a page given over to mathematical formula. In this environment the numbers are written horizontally ... from left to right. There are some slight differences between the free form version of the numbers and the block form versions. The free form version of the numbers are ...

As with the block form, they always occur in triplets. However their form doesn't vary depending on which one of the triplets the character is ... the digits are always exactly the same. There is a special egg-shape symbol for zero (actually called táu kyái, where kyái means "egg"). In free form it is not permitted to drop leading zero's ... well not triplet leading zero's, word leading zero's can of course be dropped.

Below is how the five numbers given previously appear in free form ...

And that long number mentioned in the previous section (a number from the extended set) ...

It is, of course, pronounced exactly as the block form number. That is ... aja huŋgu ifaula nàin aizautaiba wú odaija ʔomba odauzaipa yàn oilaubai mulu odaudaika ʔiwetu dù

..

Below are some more symbols used in mathematics. These would appear in a free form page (or part of a page).

..

..

The top 3 symbols in the leftmost column designate "operations". These modify a number and are placed immediately left of the number they modify. If a number has more than one operator they come in the order "minus sign", then "i", then the inverse ("1/x") symbol.

..

And below is a few examples of equations written in this notation.

..

..

..... Possibility and Obligation

..

This section is just me thinking allowed. I reckon it is finally time to get to the bottom of the English Modal Verbs.

At the start of Chapter 3 ... 3 verb forms and 3 verb constructions were given (apart from the base form ... maŋga. However these forms/constructions don't quite cover everything that needs to be expressed ... specifically we need to express possibility and obligation.

First let us look into possibility. In the diagram below the black boundary encloses all the situations where it is the ability of the subject which are relevent. Between the black boundary and the red boundary are situations where it is conditions outwith the subject which are relevant. The area inside the red boundary represents all situations that make the relevant action possible.

..

There is commonly reckoned to be 9 modal verbs in English. I have shown them below in the black boxes. I have put a red cross next to "may" and "shall". This is because they are not in the English I speak. I recognize and process these words successfully. But they never come out my mouth.

I have taken the etymology back as far as possible [ using http://www.etymonline.com ]. The red spiral things represent a shift in meaning. (Actually I am not sure about the meaning of Proto-Germanic willjan , it seems a bit suspect if you ask me).

If you want further information on this type of thing ... The Evolution of Grammar by Joan Bybee, Revere Perkins and William Pagliuca is very good.

..

..

..

..

Actually I do not use "might" very often* ... usually a clause initial "maybe", "perhaps" or "possibly" (all classed as adverbs, having scope over the whole clause) is preferred. So this leave only six of them.

The base meaning of these remaining six are ...

..

must ....... strong obligation

should .... weaker obligation

will ......... future

would .... irrealis future .......... future but blocked because of a contingency

can ....... possibility

could .... irrealis possibility .... possibility but blocked because of a contingency

..

One thing that stand out from the above chart is that the two particles with irrealis meaning end in -"ould". In fact "would" is an old past tense form of "will" and "could" is an old past tense form of "can". But how did they acquire their irrealis connotations. Well the answer is that they always occurred in irrealis situations and hence picked out irrealis connotations/meaning ... this is how grammaticization works. For example ... take (1)"can" which is the word for "root possibility" ... plus (2)"a past tense situation" ... plus (3)"a verb which represents an accomplishment" => "Yesterday I could have finished painting your bedroom". Now the question arises ... what sort of situation would occasion this sentence. Obviously if the task was accomplished, the only sentence appropriate would be "Yesterday I finished painting your bedroom". The only time "Yesterday I could have finished painting your bedroom" would be appropriate is when some contingency has come up and blocked the accomplishment of that task, such as "but I ran out of paint".

The same for "will" and "would". Back when "would" was the past tense form of "will" it actually meant "to want". So "Yesterday I wanted to finish painting your bedroom"

Actually "should" is a past tense form of "shall" and "might" is a past tense form of "may". I guess when the "shall"/"should" doublet originated "shall" had still the meaning of obligation more or less. Now the clause with the past tense "should" would inevitably be followed by a blocking contingency ... it would be followed by a "but" clause. Now this blocking contingency could come from many different directions ... and some of these directions actually decreased the force of the obligation. For an (slightly facetious) example ... "You should go and visit your mother even if she can't stand the sight of you".

In modern English "should" codes weaker obligation and is often followed by a "but" clause. "must" codes stronger obligation and is rarely followed by a "but" clause.

Like I said before "may" and to a lesser extent "might" don't figure too much in my English. But I found and example online that shows the irrealis nature of "might". Preumably when the "may"/"might" doublet originated "may" had the meaning "middle likelihood". ( from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistemic_possibility )

1) Hitler may have been victorious in World War II

2) Hitler might have been victorious in World War II

The first statement is considered wrong. However the second one is acceptable as it is taken as irrealis ... it is understood that a "but" clause is coming along (or exists somewhere) and will block the reality of the state/event.

By the way ... I would probably express (2) as "Hitler could have been victorious in World War II if ... "

..

I decided to plot out the diachronic developement of these modal verbs ... all from the history of the 9 English modal except one Mandarin modal that I came across. All these functions shown on the chart are called “modality” in the Western Linguistic Tradition. And the form they take are the "modal verbs" (historically derived from normal verbs) which are placed to the left of the main verb. Actually in present day English, these so called "modal verbs" (sometimes also called "modal auxilliary verbs" or even "auxilliary verbs") are quite un-verb-like ... I would be inclined to call them particles.

..

..

Notes on the green highlihted numbers.

1) All the above functions do seem to be connected. However if it wasn’t for the arrow joining “ability” to “obligation” the chart could be split in two … and we presumably would not be content with one cover term for everything (modality) and would think up two terms … one for each part of the chart.

The common English word “must” seems to have this provenance … that is, at one time it it stood for “ability” but through time got to stand for “obligation”. I find this change of meaning a bit strange … a bit unlikely. That is, the one who has the ability/power/possibility has an obligation to use it for the common good. I hypothesize that this shift in meaning took place when most people lived in small family groups … and hence altraism to this extent existed.

2) "may" seems to have meant "to be powerful" in the distant past. And in the recent past it seems to have meant "to have permission". I find it hard to see how this transformation of meaning came about ... unless that beyond the recent past "may" had the meaning "possibility" but by some mechanism the "possibility" semantic area shrank down to the "to have permission" semantic area.

3) It is not inevitable that "obligation" => "future" ... however it did happen with "shall".

4) I strongly object to the term "epistemic possibility" for this concept. (I want to seperate the concepts of "possibility" and "epistemic possibility" ... but looking at these term .. you would presume ... of course ... that "epistemic possibility" was a subset of "possibility"). Unsuitable terms are what makes linguistics so hard. I have made up my own term for this concept "middle likelihood" ... nothing wrong with the good old Anglo-Saxon.

5) "have" could conceivably change to 'obligation" and hence to "future". But in other languages "have" could change to "perfect aspect" and hence to "past". However all these transforms are not that common. I thought this was worth mantioning anyway.

6) "Possiblity" and "middle likelihood" are two separate things. English speakers might get confused between the two concepts because the word "possibly" is one way used to indicate "middle likelihood". And the Latinate term "possiblity" is used (by me and others) to encompass the semantic range of the word "can". But note "possibly" is not to "possible" as "quickly" is to "quick"

To understand how these two concepts are sometimes entangled ... imagine a dog inside a house... someone leaves the house and forgets to shut the front door ... now the dog "can" get out ... it has the "possibility" to get out. Given time the "probability" that the dog will go out increases with time.

..

But I don't like this example very much ... we have the vagaries of dog-nature. If we take into account things like the circadian rhythm of the dog, the weather, noises emanating from outside ... well you get a very irregular graph. To get perfect regularity we must go the subatomic root. OK ... imagine a cat in small cage ... also a small black box in the cage. This box will release poisoned gas if it detects a gamma ray in a special small chamber it has. Exactly one atom of Lawrencium 266 (Lr 266 has a half life of around 11 hours) is put in the chamber and the chamber sealed. From this point in time, the "possibility" exists that the cat has died.

This scenario gives us a nice smoothe likelihood curve. After 2 hours we can say "the cat is probably alive" ... after 5 hours we can say "maybe the cat is is dead" ... after 32 hours we can say "probably the cat is dead". Well anyway ... you get the idea ?

..

So in some languages the word denoting "middle likelihood" is derived from an earlier word meaning meaning "possible". However this path is not inevitable. For example although the adverbs "maybe" and "possibly" have a "possible" past, "perhaps" does not. I like the "middle likelihood" adverb used in Shakespeare's time ... "perchance" (< through chance).

In béu the two concepts are kept apart. The béu method of expressing "likelihood" has been given already in Ch3.10. Two particles are used ... màs and lói. Pretty straightforward.

más is used against a back ground that no event will occur. más bù is used against a back ground that an event will occur.

..

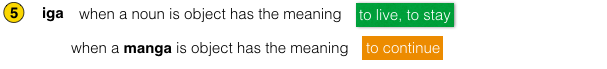

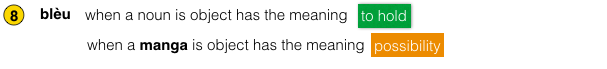

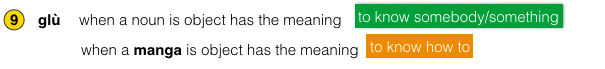

Below is a chart showing how béu handles "possible". glù signifies mental ability, mài signifies permission. blèu can be used instead of mài and glù ... it signifies root possibility.

The above three words also serve as normal verbs as well ... transitive verbs that can take a noun as an object. glàr jono = I know John ... maryə toilia = I got some books ... blara toili = I am holding a book

blèu when followed by a noun has the meaning "hold in your hand" ... the idea is that when you hold something in your hand, you have total mastery over it. I extended the meaning and when blèu is followed by a verb it takes the meaning "root possibility".

Note ... in English "must" has two distinct functions. It codes "obligation" as in "You must visit your Mother" and it codes a "sort of likelihood" as in "You must be hungry". The last one means 100% certainty but it is also a bit like a question. It is expected/hoped that the 2nd person will reply in the affirnative. Also what is asserted has been "assembled" by the 1st person from diverse clues/facts. For instance ... (1) The first person has just got off a train ... (2) It was a long journey ... (3) The train was delayed in the middle of nowhere by an additional 5 hours ... (4) There was no buffet car on the train ... (5) There were no stops apart for alighting passengers.

If the 2nd person answers in the affirmative, the 1st person will be a bit chuffed. He is a bit Sherlock-Holmes-like.

In béu, the equivalent of "must" (byó) only has the "obligation" function. For the other function you would append the -n evidential to the verb. Also perhaps you would add the YES/NO question particle  to the end of the utterance. In the chart about the diachronic developement of the modal verbs I have not included this "sort of likelihood" function. If I had I would have given it its own circle.

to the end of the utterance. In the chart about the diachronic developement of the modal verbs I have not included this "sort of likelihood" function. If I had I would have given it its own circle.

..

..... The particle gò

..

This particle introduces a clause. "gò + clause" usually take the syntactic position normally taken up by a single noun. For example the object of glù "to know" can be a person or a location ...

jono gár = I know John

but it is also possible to know a fact ...

gár gò jene r jini = I know that Jane is clever

In English the word "that" is used for this function. However "that" has many other uses as well. gò has really only one function.

..

It is not a productive process but many nouns in béu were historically derived from verbs. For example ... solbe "to drink" versus solbo "a drink". It might be that gò was derived from gàu "to do" and once had a meaning like "action". If this is true then gò was co-opted to become a particle introducing clauses under the same circumstances as the Japanese word "koto" ....

..

| ano | hito-ga | hon-o | kai-ta | koto-ga | yoku | sirarete | iru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yon | person-NOM | book-ACC | write-ACC | CI-NOM | well | known | COP |

=> It is well known that that person wrote a book

..

With ... NOM = nominative : ACC = accusative : CI = clause introducer : COP = copula

..

In Japanese "koto" as well as being a particle is also a noun meaning "affair" or "matter". However in béu ,gò has long since lost it's nounhood.

..

..... Twelve important verbs

..

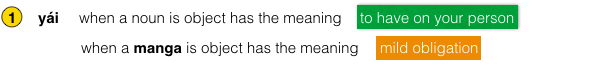

[ perhaps meaning "to have easy access to" if taking about a larger object ]

[ perhaps meaning "to have easy access to" if taking about a larger object ]

jonos yora toili = John has a book (on him)

jonos yora jò nambon = John should go home

..

jonos byór fanfa = John owns a horse

jonos byora jò tunheun = John must go to the townhall

..

jenes core nambo yindos = Jane left home (earlier today)

jenes core kodai idai = Jane stopped work at 4 o'clock (in the afternoon)

..

jonos dori nambo ezai = John arrived home at ten o'clock (at night)

jonos dori solbe tàin léu dinda = John started to drink three days ago

jonos doru kodai jáus léu dinda = John will start working in three days time.

jonos dorua kodai jáus léu dinda = John intends to start working in three days time.

weuno dori doika = the engine started .... note that the verb doika "to walk" or "to operate" is necessary here

..

jonos igor london = John stays in London

jonos igor doika nambon = John keeps on walking home = John continues to walk home

..

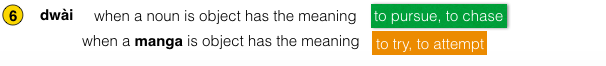

waulos yanfa dwora = The dog is chasing the hare

waulos yanfa dwora holda = The dog is trying to catch the hare

..

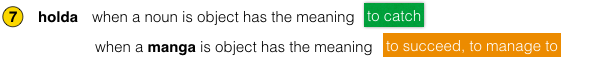

waulos yanfa holdoryə = The dog has caught the hare

holdari bunda nambo = I managed to build a house

nùa holdari holda = I managed to catch the mouse

..

blara biabia = I've got a butterfly in my hand

blàr bunda nambo = I can build a house

blèu can also take a complement clause [ CC ] that represents a fact. This CC has the complementizer gò. In this situation it is equivalent to the "believe"

blàr gò jene r jini = I believe that Jane is clever

..

jenes glòr tomo = Jane knows Thomas

jenes glòr laigau = Jane knows calculus

jenes glòr kludau = Jane knows how to write

This verb can also take a complement clause [ CC ] that represents a fact. This CC has the complementizer gò ...

glàr gò jene r jini = I know that Jane is clever

..

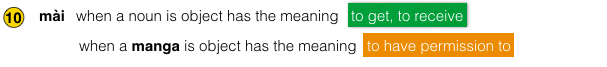

maryə toilia = I have received some books

maryə toilia nufi = I have received some books from them

màur jò nambon idai = We are allowed to go home at 4 o'clock

Note ... the meaning of mài with a maŋga is the passive of náu (next verb) with a maŋga when translated into English.

This verb can also take a complement clause [ CC ] ... again introduced by gò. This can happen in the situation where you are responsible for someone else (usually an offspring) and someone in authority has given permission (via you) for your offspring to do something (or not do something). For example ...

maryə gò jonos bù yora jò haundan tomorrow = I have been told that Johnny doesn't have to go to school tomorrow

..

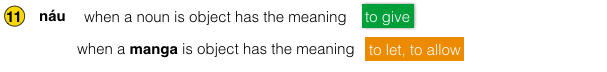

This is a 2 place verb. Well the recipient is in the dative, so that doesn't count towards the valancy ... right ? But unlike mài ... this one sort of needs a dative to make sense.

ós pàn nore toilia = He gave some books to me (earlier on today)

ós pàn nore jò nambon = He let me go home = He allowed me to go home

*jonos nore jò nambon pàn = ... béu does not like the dative separated from the verb by a two-word object ... well not when the dative is one-word anyway.

This verb can also take a complement clause [ CC ] introduced by gò.

ós pàn nore gò jonos bù yora jò haundan tomorrow = He told me that Johnny doesn't have to go to school tomorrow

..

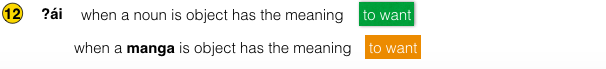

jaja ʔór fanfita = My daughter wants a pony

jaja ʔór jò nambon = My daughter wants to go home

This verb can also take a complement clause [ CC ] introduced by gò.

jaja ʔór gò kaka jò nambon = My daughter wants her younger sister to go home

..

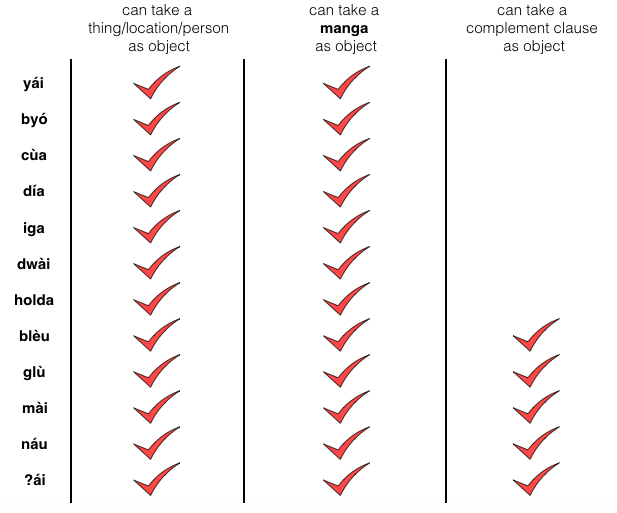

Below is a summary of what type of object these verbs can have ...

..

Notice that when one of these words takes a maŋga, the maŋga must immediately follow. As usual, if the maŋga has an object it must immediately follow the maŋga. For all these twelve verbs, the maŋga has no subject ... or the subject is the same as the main verb.

In English usage (in fact all the Germanic languages) ... the way to negate modal words is a confusing. Consider "She can not talk". Since the modal is negated by putting "not" after it and the main verb is negated by putting "not" in front of it, this could either mean ...

(a) She doesn't have the ability to talk "or" (b) She has the ability to not talk

Note ... Only when the meaning is (a) can the proposition be contracted to "she can't talk". In fact, when the meaning is (b), usually extra emphasis must be put on the "not". (a) is the usual interpretation of "She can not talk" and if you wanted to express (b) you would rephrase it to "She can keep silent". This rephrasing is quite often necessary in English when you have a modal and a negative main verb to express.

In béu it is possible to negate the active verb and to negate the maŋga separately. The maŋga negator is jù. This is the same negator used for nouns. It only has scope over the NP following it (unlike bù which has scope over the whole clause). For example ...

jenes bù blòr flò coko => Jane can't eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability to eat chocolates) ... for example she is a diabetic and can not eat anything sweet.

jenes blòr jù flò coko => Jane can not eat chocolates (Jane have the ability not to eat chocolates)... meaning she has the willpower to resist them.

jenes bù blòr jù flò coko => Jane can not not eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability, not to eat chocolates) ... meaning she can't resist them.

And another example ...

(jés) bù byér flòn jodoi = You lot don't have to feed the animals

(jés) byér jù flòn jodoi = You lot mustn't feed the animals ... (this is for a general/timeless situation ... kyà flòn jodoi would be used for a "here and now" situation)

(jés) bù byér jù flòn jodoi = You lot can feed the animals if you want

..

..... The adverbs

There are 4 types of word that function as adverbs in béu.

1) There are adjectives which are changed into adverbs by suffixing -we. For example ...

saco = quick

sacowe = quickly

THIS type of adverbs can have any position within a sentence. However if they immediately follow the verb which they are qualifying, the suffix is deleted. For example ...

doikor saco nambon = doikor nambon sacowe = sacowe doikor nambon = she is walking quickly home

2) There are nouns which are changed into adverbs by suffixing -we. For example ...

deuta = soldier

deutəwe = "in the manner of a soldier"

Note that the final vowel in deuta changes here. This is because as well as being a suffix, wé is a noun in its own right meaning "way" or "method" (see the section on word building)

Just as saco is an adjective which is considered an adverb when immediately following a verb, so deutəwe is an adverb that is considered an adjective when immediately following a noun.

Also a noun is formed by suffixing -mi to the end.

deutəwemi = soldierliness

3) One of the functions of a nouns with pilana 1 => 8 + 15 is as an adverb. This type of adverb must follow the verb immediately. In a similar manner to type 2), if this form comes after a noun it is considered an adjective. For example ...

moŋgos flor halma pazbamau (the gibbon eats an apple on the table) pazbamau is an adjective describing where the apple is.

moŋgos flor pazbamau halma (the gibbon is eating an apple on the table) pazbamau is an adverb describing where the "eating" is taking place.

Note ... In English, the sentence "the monkey eats the apple on the table" is ambiguous.

Go thru the other pilana ???

4) This type of adverbs are nouns that are stand for time periods. For example tomorrow, yesterday, the past et. etc. Basically when they are not copula subjects, copula complements or in the ergative case, they are adverbs.

5) Words such as "often" ??? are particles ... as are adverbs of time ... such as yildos "morning" ... falaja "afternoon" ... jín "instant" ... jón "moment"

..

..... Introducing participants and tracking them through a body of text

..

In a basic clause béu shows definiteness by putting an argument before the verb, and shows indefiniteness by putting an argument after the verb*. [There is a long discussion about definiteness in Ch 5]

jonos timpore fanfa = John hit a horse (earlier today)

jonos fanfa timpore = John hit the horse (earlier today)

I guess it depends on whether the argument is known to the hearer (this controvenes what I say in CH_5 I think ??)

Now if the speaker has a particular horse in mind, and the hearer knows nothing about the horse ... and the speaker plans to expand on the horse to make it definite to the hearer ... then the argument is marked by the redundent word ?à "one". For example ...

jonos timpore ?à fanfa = John hit this horse (earlier today) ... Note that English uses "this" or "these" in a similar way ... as an "introductory" particle.

And if the item being introduced is plural, it is marked by the redundent word nò "number". For example ...

bware nò fanfai yildos = This morning I saw these horses ... [ what about jé ?? ]

..

Now suppose we are telling a funny store involving a horse fanfa and a dog waulo. These protagonists will have been introduced by the above method and are "known" to both speaker and hearer. Now suppose that another dog enters the story. How can we handle this. Well one way to do it is to introduce the new protagonist after the verb as waulo lò "other dog". And from then on the new dog will be referred to as waulo hói and the original dog as waulo ?à ... "second dog" and "first dog" respectively.

Another method of tracking these participants is available. In fact it is preferred but not always possible to implement. If the new dog had some unusual characteristic(s) ... it can be tagged thus. So the new protagonist could be introduced after the verb as waulo lò_ waulo àu jutu "other dog, big black dog". And from then on the new dog would be referred to as waulo àu jutui and the original dog would be referred to as waulo ?à ... or (in this case) maybe just waulo.

*This method of showing definiteness is only available for the S A and O arguments of a clause. For peripheral arguments in a clause (indeed for nounal elements in a NP) the usual procedure is to assume definite if unmarked but indefinite if there is èn in front. ( èn = some, ín = any ).

[ wenfo "new" and yompe "previous, former" ... are not used ? ... are used when ?? ]

..

... Antonym phonetic correspondence

..

In the above lists, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning from each other. However in béu there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | ai | |||

| f | e | |||

| b | eu | |||

| g | u | |||

| d | ua | high tone | ||

| l | =========================== | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ia | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | i | |||

| k | oi | |||

| p | o | |||

| t | au | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

Note ... The original idea of having a regular correspondence between the two poles of a antonym pair came from an earlier idea for the script. In this early script, the first 8 consonants had the same shape as the last 8 consonants but turned 180˚. And in actual fact the two poles of a antonym pair mapped into each other under a 180˚ turn.

An adjectives is called moizana in béu .... NO NO NO

moizu = attribute, characteristic, feature

And following the way béu works, if there is an action that can be associated with noun (in any way at all), that noun can be co-opted to work as an verb.

Hence moizori = he/she described, he/she characterized, he/she specified ... moizus = the noun corresponding to the verb on the left

moizo = a specification, a characteristic asked for ... moizoi = specifications ... moizana = things that describe, things that specify

nandau moizana = an adjective, but of course, especially in books about grammar, this is truncated to simply moizana

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences