Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions: Difference between revisions

| Line 958: | Line 958: | ||

But first a bit about timekeeping in general ... | But first a bit about timekeeping in general ... | ||

Below I have given a '''jekas'''. '''jekas''' can be translated as "date" or "time". A '''jekas''' can define a time from circa 200,000 years ago to 200,000 year in the future down to the nearest 50 second period. For example '''omba bene odaudai dimaku ?oli sunaba ajau''' is a '''jekas'''. | Below I have given a '''jekas'''. '''jekas''' can be translated as "date" or "time". A '''jekas''' can define a time from circa 200,000 years ago to 200,000 year in the future down to the nearest 50 second period. For example '''omba bene odaudai dimaku ?oli sunaba ajau''' is a '''jekas'''. It is analyzed below ... | ||

.. | .. | ||

| Line 986: | Line 986: | ||

2) (negative/positive) ... these can be dropped if it is known from context or from a tense affix, whether we are talking about the past or the future. By the way ... negative corresponds to the past. | 2) (negative/positive) ... these can be dropped if it is known from context or from a tense affix, whether we are talking about the past or the future. By the way ... negative corresponds to the past. | ||

3) "the number of the 128 year long cycle". '''odaudai''' = 550<sub>12</sub> = 780<sub>10</sub>. As time zero in the '''béu''' calendar is 22 Dec 2083 | 3) "the number of the 128 year long cycle". '''odaudai''' = 550<sub>12</sub> = 780<sub>10</sub>. As time zero in the '''béu''' calendar is 22 Dec 2083, we are talking roughly about a hundred thousand years in the future here. | ||

4) "the particular year of the 128 cycle". '''dimaku''' means python and is the 100th year of the 128 year cycle. | 4) "the particular year of the 128 cycle". '''dimaku''' means python and is the 100th year of the 128 year cycle. | ||

5) "the particular '''sabata''' of the year" ... there are 5 | 5) "the particular '''sabata''' of the year" ... there are 5 '''sabata''' a (73 day long period) in one year ... '''?oli pwè gú gamazu''' and '''yika''' | ||

6) '''sunaba''' is the sixteenth day of the 73 day '''sabata''' ... [ In chewa, sabata means "week" ... and Yes, I know this is very unlikely to have Bantu provenance ] | 6) '''sunaba''' is the sixteenth day of the 73 day '''sabata''' ... [ In chewa, sabata means "week" ... and Yes, I know this is very unlikely to have Bantu provenance ] | ||

| Line 998: | Line 998: | ||

[ By the way ... if you put pluralize '''ajau''' you get '''ajau.a'''. This word corresponds to the time period between 08:00 and 10:00 ... '''ifau.a''' = 10:00 => 12:00 ... '''ibau.a''' = 12:00 => ... (well you get the idea) | [ By the way ... if you put pluralize '''ajau''' you get '''ajau.a'''. This word corresponds to the time period between 08:00 and 10:00 ... '''ifau.a''' = 10:00 => 12:00 ... '''ibau.a''' = 12:00 => ... (well you get the idea) | ||

.. | |||

'''jé''' used | |||

Now a '''jekas''' can be put at the periphery of a clause to identify when an action is happening. This is what they are nearly always used for. However '''jekas''' are hardly ever given in full. For example it might be deemed sufficient just to give the time of the day. When time of the day occurs by itself it MUST be preceded by the particle '''jé'''. | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! jene-s || d-o-r-e || jé || ajau | |||

|- | |||

| Jane-{{small|ERG}} || arrive-{{small|2SG-IND-PST}} || at || 08:00 || | |||

|} => Jane arrived at eight in the morning | |||

Also it might be deemed sufficient just to give the day. It this case '''jé''' can be used. It is maybe used about 50% of the time that the day occurs alone or when the day occurs followed by the time of day. | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! g-a-r-u || (jé) || geufa | |||

|- | |||

| do-{{small|1SG-IND-FUT}} || on || the seventh day of the month || | |||

|} => I will do it on the seventh | |||

.. | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

! tomo-s || d-o-r-i || (jé) || geufa || ajau | |||

|- | |||

| Thomas-{{small|ERG}} || arrived-{{small|2SG-IND-PST}} || on || the seventh day of the month || at 08:00 || | |||

|} => Thomas arrived on the seventh day of the month at eight in the morning | |||

Only in the three situations above do you get '''jé''' introducing a truncated '''jekas'''. | |||

.. | |||

.. | |||

DAY TEN = the tenth day = 7 minutes into the day => '''jé''' always precedes the "hour numbers" (well if the name of the day '''kika''' exists it can be dropped) | DAY TEN = the tenth day = 7 minutes into the day => '''jé''' always precedes the "hour numbers" (well if the name of the day '''kika''' exists it can be dropped) | ||

| Line 1,023: | Line 1,059: | ||

.. | .. | ||

.. | .. | ||

... | ... | ||

Revision as of 19:48, 26 August 2017

..... Questions

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 8 question words ... "which", "what", "who", "whose", "where", "when", "how" and "why". *

..

..

If you hear any of these words you know you are being solicited for some information. These words have no other function apart from asking questions.

..

Notice that there is no word for "how" or "why" in the above table. These are expressed by wé nái and nenji** respectively.

On the other hand, béu has single words where English has "how much" and "what kind of".

..

The first two have dual forms ... nén and mín are the absolutive forms and nós and mís are the ergative forms.

..

Now ʔai? always comes utterance final ... ʔala always comes between two NP's. This leaves 7 QW's. Of these nén mín dá and kyú are fronted***

And láu kái dá and nái **** are found in their respective slots within a NP ...

Note that when questioning who owns something yó mín occurs within the NP ... this is a sort of secondary usuage of mín and is not considered here.

Also note that dá can be either fronted or within a NP. When fronted it asked where the action takes place. When within a NP it asks about the NP's location. For example ...

..

| jene-s | halma | dá | hump-o-r-u |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jane- ERG | apple | where | eat-3SG-IND-FUT |

=> where is the apple that Jane will eat

A suitable answer to the above is pazbala "on the table"

| dá | jene-s | halma | hump-o-r-u |

|---|---|---|---|

| where | Jane- ERG | apple | eat-3SG-IND-FUT |

=> where will Jane eat the apple

A suitable answer to the above is pazba?e "at the table"

..

Statement .... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 .... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 .... minin bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 .... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... bàus glán nori láu alha = How many flowers did the man gave the woman ?

Question 5 ... bàus glán nori alha kái = What kind of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 6 ... dá bàus glán nori alha = Where did the man give the woman flowers ?

Question 7 ... kyú bàus glán nori alha = When did the man give the woman flowers ?

Question 8 ... í glá nái bàus nori alha = to which woman did the man gave the flowers ?

Question 9 .... há bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 10 .... bàus glán nori alha ʔala cokolate = Did the man gave the woman flowers or chocolate ?

Question 11 ... ʔír doika ʔala jaŋka = Do you want to walk or run

Question 12 .... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 13 ... minji bàus glán nori alha = Why did the man give the woman flowers ?

..

*Note ... there was also a "whom" until quite recently. Also some people count "whose" as a separate QW ... however it shouldn't be ... it is just "who" + "z" (the genitive clitic).

**Well nenji is the normal traslation of "why". In certain situations you might hear minji ... when it is knows that an action/state is for somebody's benefit and no other reason is applicable.

***Around one third of the world's languages front a question word. English is one of them. [ see http://wals.info/feature/93A#2/25.5/151.2 ]

****Actually these 4 words often stand alone. But when they do, they are still considered within a NP ... only that the rest of the NP has been dropped.

..

In the table of question words above I have marked the top two and the bottom two off. The top two because they are the QW's par excellence ... they are used more than the other QW's. The bottem two because their answers are restricted to two items. ?a is restricted to "yes" or "no" ... ?ala to one of the NP's that sandwich it.

láu kái dá kyú and nái each have low tone equivalents. These particles are important grammatical words in their own right and they each are related to their high tone equivalent in subtle ways. Basically làu introduces the "partitive construction" , kài means "like" or "similar", dà introduces an adverbial phrase of location, kyù introduces an adverbial phrase of time, and, nài is a "relativizor".

... nài

..

In English "who", "that" and "which" are relativizors ... a particle that introduced a relative clause. For example ...

"The man who ate the chicken"

"The chicken that was eaten"

"The knife and fork which were used to eat the chicken"

..

In béu there is only one relativizer, which is nài. For example ...

glá nài bàu timpori = "The woman who the man hit"

Now ... in the above ... glá is being modified by nài bàu timpori. nài bàu timpori implies a clause bàu timpori glà.

To construct a relative clause for glá, nài is inserted between the noun and clause, and the noun is dropped from the clause.

Now in the above example ... the roll of glá in the clause is absolutive (i.e. glá is unmarked). However if the roll of the noun ... in the clause ... is one defined by one of the 17 pilamo, this pilamo must be suffixed to nài. For example ...

..

pi ... the basket naipi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

la ... the chair naila you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

... mau / goi / ce / dua / bene / komo ...

tu ... báu naitu ò is going to market is her husband = the man with which she is going to town is her husband ... kli.o naitu he severed the branch is rusty

ji ... The old woman naiji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

-s ... báu nàis timpori glá_rò jutu sowe = The man that hit the woman is very big.

wo ... The boy naiwo they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

-n ... the woman nàin I told the secret, took it to her grave.

fi ... the town naifi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

?e ... nambo naiʔe she lives is the biggest in town = the house in which she lives is the biggest in town

-lya ... the boat nailya she has just entered is unsound

-lfe ... the lilly pad nailfe the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond ... (note to self : improve this, work out translation for all these concepts)

..

If the roll of the noun (in the clause) is one not specificated by the 17 pilamo then the noun can not be dropped entirely, it must be represented by a pronoun. For example ...

| gwài | nài | polg-u-r-a | ala | ʃì |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| the islands | REL | sail-1PL-IND-PRES | between | them |

Literally "the islands that we are sailing between them" ... or ... in good English ... "the islands that we are sailing between"

| gawa | nài | toti-s | lent-o-r-e | tài | nù |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| the women | REL | children-ERG | play-3SG-IND-PAST | in front of | them |

Literally "the women that the children played in front of them" ... or ... in good English ... "the women that the children played in front of"

..

| há | gawa | nài | toto-s | lent-o-r-e | tài | nù | waulo | dainuru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERG | the women | REL | children-ERG | play-3SG-IND-PAST | in front of | them | dog | kill-3PL-IND-FUT |

Literally "the women that the children played in front of them, will kill the dog" ... or ... in good English ... "the women that the children played in front of will kill the dog"

..

In English we have what is called a headless relative clause. béu has this also ...

nài bwair rò nài mair = "what you see is what you get"

nàis bwor rò nàis mair = "that which sees is that which gets"

ò nàis bwor rò ò nàis mor = 'he that sees is he that gets" ... [this one not headless of course ... a pronoun has been added to narrow down what exactly we are talking about]

..

... kyù

..

kyù = when

toili gìn naru kyù twairu = I will give you the book when we meet ............................ kyù twairu can be considered an adverb of time.

..

... dà

..

dà = where

pà twahu dà yildos twaire = meet me where we met in the morning ........................ dà yildos twaire can be considered an adverb of place.

..

... kài

..

kài = as, like

| jono | r | kài | dada | ò |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| john | is | like/as | older brother} | his |

=> John is like his older brother .................................................................... in this example kài and what follows can be considerd an adjective.

| jono | r | kài | dada |

|---|---|---|---|

| john | is | like/as | older brother} |

=> John is like my older brother .................................................................... in this example kài and what follows can be considerd an adjective.

...

| jono-s | klud-o-r | kài | tomo-s | klud-o-r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | writes-3SG-IND | like/as | thomas-ERG | writes-3SG-IND |

=> John writes like Thomas writes ........................................................ in the following examples kài and what follows can be considerd an adverb of manner.

| jono-s | klud-o-r | kài | tomo-s |

|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | writes-3SG-IND | like/as | thomas-ERG |

=> John writes like Thomas ...........................................Note ... the final verb has been dropped but Thomas keeps the ergative marking.

| jono-s | huz-o-r | kài | kulumo |

|---|---|---|---|

| john-ERG | smoke-3SG-IND | like/as | chimney |

=> John smokes like a chimney

| taud-o-r-a | kài | hunwu | tú | húa | gayana |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to be annoyed-3SG-IND-PRES | like/as | bear | with | head | aching |

=> he/she is annoyed like a bear with a headache

(Note to self .... is gayana still valid)

| bù | ?oim-o-r-a | kài | fiʒi | mù | moze |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| not | to be happy-3SG-IND-PRES | like/as | fish | out | water |

=> he/she is unhappy like a fish out of water

| gì | r | gombuʒi | kài | jono |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| you | are | argumentative | like/as | John |

=> you are argumentative like John .............................. i.e. in the same manner ... for example ... shouting over other people when they try and put forward their arguments

Note ... the wide variety of things being compared ... clause to clause : clause to noun : noun to noun

..

... làu

..

Question ... ò r láu bòi "how good is he ?"

Answer .... ò r làu bòi jonowo "he is as good as John"

làu means "to such an extent or degree" and is used in front of adjectives. The below are all single clauses.

..

jono r làu bòi jenewo = "john is as good as jane"

tomo r làu fat _ plùa bù blòr doika = "thomas is so fat that he can not walk"

??? Mmmmh ... as a conjunction plùa has been superceded by badas ... badas not appropriate here .... neither is gò ???

The way to do it is ... tomo r fat làu bù blòr doika

But this would imply ...

jono r bòi làu jene = "john is as good as jane"

ʔazwo pona làu hói hoŋko = two cups of hot milk

..

There are three main usages for this particle. The three examples above demonstrate these three usages. ..

..

Note ... all the above should be actually two clauses but because of truncation ... [ a chimney ] <= [ a chimney smokes ] ... [ before ] <= [ she used deceit before ] ... [ John ] <= [ John is argumentative ] ... [ agreed ] <= [ all parties agreed ] ... [ John ] <= [ John is ] ... these constructions often appear as if only a NP follows kài.

Usually for particles that can either be followed by a NP or a clause, I add gò after the particle when a clause follows. This is to prevent errors in comprehention. For example jì means "for" and is followed by a NP (usually a person). I have jì gò meaning "in order that" ... jì gò being followed by a clause. In béu the first word of a clause is often a noun. If I had jì meaning "in order that" there might be misunderstanding (albeit temporary). English does this also in many constructions [ I should go into this more fully ??? ]. Of course I could have a totally different particle for "in order that" but I wanted to emphasis the semantic overlap between these to constructions.

But there is no chance of misunderstanding when kài is heard ... it is always followed by a clause. Even in (5) what we have is a clause. The clause is jono r (with the r dropped). Actually kài means "in the manner or roll specified" ... the last bit added to include cases like (5).

..

Note ... kài can not be followed by an adjective.

There are 5 nouns that are associated with 5 of these above question word / indefinite pairs. làus = amount, quantity : kàin = kind, sort, type : dàs = place : kyùs accasion, time : sàin = reason, cause, origin

These 5 nouns are never followed by nài. The table below is interesting. It shows the logical equivalence of a hypothetical expession (on the LHS) and the logical equivalent actually used (on the RHS).

..

*làus nài => làu

*kàin nài => kài

*dàs nài => dà

*kyùs nài => kyù

*sàin nài => sài

..

There are two adjectives associated with these question word / particle pairs. laubo meaning "enough" and kaibo meaning "suitable".

Also there are two nouns associated with these question word / particle pairs. lauja meaning "level" and kaija meaning "species/model".

sài

..

sài = because of

dari solbe sài ò = I started to drink because of her .................................................. sài ò can be considered an adverb of reason.

Note ... sài means "because of" ... sài gò means "because"

..

..

To say something like "john is as good at writing as jane" you have to use ʔà (or ʔàbis) ... see the next section.

..

Note that 3) and 8) do not mean the same thing ... kài defines a multi-characteristic concept (thing or action) while làu specifies position* on a uni-characteristic scale. [* or "degree" or "amount"]. So làu introduces only a quantity and kài intruduces a quality or manner.

..

..

I find the above table interesting. It is skewed ... OK pí wé nài ("in the manner that") can be used but it hardly ever is. Usually kài = "in the manner that". Why is it skewed ? My answer is ...

"For everyone the most important things around them are other people. And the most important "attribute" of a person is "how" they behave."

Hence kài has supplanted pí wé nài.

Also notice that any adjective outwith a NP has to be introduced by the copula, hence sàu kài instead of simply kài.

..

Note ... nù r làu jutu saduwo and nù r jutu kài sadu do not mean the same thing ... nù r làu jutu saduwo would be said when you have one specific sadu "elephant" in mind.

So nù r làu jutu saduwo => "they're as big as the elephant" ... nù r jutu kài sadu would be said when you are talking about elephants in general. So => "they're as big as elephants"

..

Good, Better, Best

..

làu is part of a larger paradigm ... the comparative paradigm ... demonstrating with the help of bòi ("good") ...

..

| >>> | boimo | best |

| > | boige | better |

| = | làu bòi | as good |

| < | boizo | less good |

| <<< | boizmo | least good |

..

The top and the bottom items are the superlative degree and so have no "standard of comparison".

The fourth one down is used less frequently than the second one down. This is because its sentiment is sometimes expressed by negating the third one down. For example ...

gì bù r làu bòi pawo = "you're not as good as me" can be used instead of gì r boizo pawo "you are less good than me"

[ actually gì r boizo pawo would be the normal way to express this sentiment. But gì bù r làu bòi pawo would be used, for example, as a retort to "I'm as good as you" ]

The superlative forms are found as nouns more often than as adjectives. That is boimo and boizmo are rarer than boimos and boizmos. (see table below)

..

boimos = the best : bàu boimo = the best man

boizmos = the least good : bàu boizmo = the least good man

..

[ you are argumentative like John but you are even worse ] ... explain this more

... ?ài

..

The same or not the same

..

ʔài = "same"

bù ʔài = "different"

Note ... for "the other", NP before the verb : for "another", NP after the verb)

1a) jono lé jene sùr ʔài bèn = "John and Jane are the same" ... logically the bèn is unnecessary, but it is often included ... euphony.

1b) jono r ʔài jenewo = "John is the same as Jane"

The above two examples are ambiguous as to whether John and Jane are the same w.r.t. one characteristic or the same w.r.t. all characteristic.

2a) jono lé jene r ʔài jutuwo = "John and Jane are the same size"

2b) *jono r ʔài jenewo jutuwo = "John is the same as Jane, sizewise" = "John is the same size as Jane"

The above is not allowed ... there is a rule saying that you can't have two consecutive -wo endings. So 2b) has to be re-assembled as ...

jono r làu jutu jenewo .... see Ch2.11.1

[Note jutuwo is derived from jutumiwo but the mi "ness" is invariably dropped.

ʔàibis = similar

ʔài dù = exactly the same

ʔaimai = similarity

lomai = difference

To say something like "John is as good at writing as Jane" we can not say *jono r làu bòi jenewo kludauwo [ ??? ] [ two consecutive -wo no good ? ]

You must use a sort of topic comment construction.

wo kludau bòi_jene r ʔài jonowo or wo kludau bòi_jene lé jono r ʔài

..

..... Totality ... collectively or individually

..

Sometimes we want to talk about all members of the category "noun" acting (or being acted upon) COLLECTIVELY.

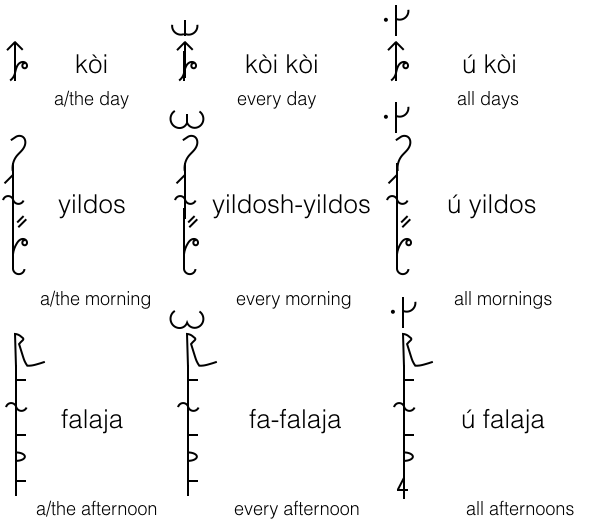

For this we use the particle ú before the plural of the noun. For example ...

moltai = a/the doctor

moltai.a = doctors

ú moltai = all doctors

Note ... the same word, when appended to a noun, means "the whole" or "entire". For example ...

falaja ú = all morning

..

The opposite of the above, is when all members of the category "noun" is acting (or is being acted upon) INDIVIDUALLY.

By doubling the noun (or the first part of a noun) you give what can be called a distributive meaning.

Some examples ...

kòi = day

kòi kòi = every day

moltai = doctor

moltai moltai = each doctor

falaja = afternoon

fa-falaja = every afternoon

Notice that for words over two syllables, only the first syllable is prefixed.

..

The "word-hood" of these duplications is murky. When the word in its entirety is dublicated, they are written as to seperate words. When a word is only partially duplicated I write it as a hyphenated word. In the béu script a special symbol is used to indicate duplication.

Single syllable words retain their tone when duplicated ... which indicates two separate words. However you also get phonological processes that are usually only word internal. That is to say, these structures show "sandhi".

For example ...

yildos yildos (every morning) would be pronounced / jildoʃ jildos /.

bàu bàu can be pronounced bàu vàu ... [ If you remember ( Chapter 1.1) b and v are in free variation ]

là bàu bàu = "on every man" .... indicates that bàu bàu is multi-word as the pilana is in its stand alone form.

Anyway ... these constructions are never written out in full. Instead a special symbol is placed above the simple noun. This symbol can vary a bit, depending on the font being used : it can vary from a lower half circle bisected by a vertical stroke to a shape that looks a bit like the Arabic shaddah.

For example ...

..

It some contexts, semantically, it does not matter whether the individual or the collective form is used. When this is the case, the default choice is "individual" structure. ú tends to be used with tangible nouns more, it is hardly ever used with nouns denoting periods of time.

Note (as in English) the plural verb form is used for the collective structure, the singular verb form for the individual structure. For example ...

ú bàu súr = all men are

bàu bàu sór = every man is

NOTE TO MYSELF

Every language has a word corresponding to "every" (or "each", same same) and a word corresponding to "all". "all" emphasises the unity of the action (especially when the NP is S or A) while "every" emphasises the separateness of the actions. Now it is not always necessary to make this distinction (perhaps in most cases). It seems to me, that in that case, English uses "every" as the default case (the Scandinavian languages use "all" as the default ??? ). In béu the default is "all" ù.

The meaning of this word (in English anyway) seems particularly prone to picking up other elements (for the sake of emphasis) with a corresponding lost of power for the basic word when it occurs alone. (From Etymonline EVERY = early 13c., contraction of Old English æfre ælc "each of a group," literally "ever each" (Chaucer's everich), from each with ever added for emphasis. The word still is felt to want emphasis; as in Modern English every last ..., every single ..., etc.)----

TO THINK ABOUT

?à ?à bàu hù ?ís = any man that you want ( ?ís ... "you would want" ???? )

?ài ?ài bàu hù ?ís = any men that you want

?ài bàu = some men

..

..... lé .... lú .... ló

..

Earlier we have seen that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilana affixed to them. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilana then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

jonos jenes solbur moze = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of an affixed pilana, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lé should be placed between them. For example ...

jenes solbori moʒi lé ʔazwo = "Jane drank water and milk"

jonos jenes bwuri hói sadu lé léu ʔusʔa = John and Jane saw two elephants and three giraffes.

[ Compare the above two examples to á jono jene solbori moze = Jane's John drank water ... i.e. The John that is in a relationship with Jane, drank water ]

This word is that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

..

Note ... in the béu script, the "o" before "r" is always dropped. This is just a sort of short hand thing.

..

The following construction is also found.

lé moze lé ʔazwo = "both water and milk"

The above construction emphasizes the "linking" word lé

Another linking word is lú meaning "or".

jenes blor solbe moze lú ʔazwo = "Jane can drink water or milk"

The following construction is also found.

lú moze lú ʔazwo = "either water or milk"

The above construction emphasizes the "linking" word lú

There is another word that corresponds to the English "or". This is ʔala and it is a question word. For example ...

ʔís moze ʔala ʔazwo = "would you want water or milk"

And the answer expected of would be either "water" or "milk"

Say you were asking somebody if they were thirsty and you had only water or milk to give them. Then you would say ... ʔís moze lú ʔazwo ʔai@

The expected answer to the above question would be either "yes" or "no" (as is always the case when you have @ ( @ is pronouced a bit like ʔai but has contour tone instead of a normal high tone, it has a special symbol and I am using "@" to represent this symbol in my transliteration)).

Now if the question was "would you want water or milk, or both" you should say ...

ʔís mose ʔala ʔazwo ʔala leume

But sometimes (either because of the laziness of the speaker or because the likelyhood was not considered) ... ʔís moze ʔala ʔazwo ʔala leume comes out as ʔís moʒi ʔala ʔazwo.

So ʔís leume (I would like both) is an acceptable answer to the question ʔís moze ʔala ʔazwo

If the questioner would like to rule out the answer ʔís leume he would use the construction .

ʔís ʔala moze ʔala ʔazwo

So ʔala before the first item does exactly the same as lé or lú before the first item : it emphasizes the linking word.

..

... "no"

..

In béu, jù corresponds to "no".

"neither water nor milk" would be translated as jù moʒi jù ʔazwo

..

... lists

..

So far we have restricted ourselves to two items. We can summarize the system for two items as below ...

..

| lé | giving | 2 | items | |||||

| lú | giving | 1 | item | ..... | ʔala | asking for | 1 | item |

| jù | giving | 0 | items |

..

However we can join up more than two items. When more than two items are joined by the above 4 linking words, it is considered good style to have the linking word before the first item and the last item, before each item (except the first and the last) should be a slight pause (I call it a gap ... see "punctuation and page layout" earlier on this page).

For example ...

jenes bwori lé ifa sadu _ uba ʔusʔa _ ega moŋgo lé oda gaifai falaja dí = Jane saw two elephants, three giraffes, four gibbons and five flamengos this morning.

..

... other

..

ló = other

lói = others

kyulo = again

welo = otherwise

..

..... Another passive

..

We have seen the impersonal passive above (where the vowel before the r becomes a schwa.

However there is another passive form made with the verb jwòi "to undergo" plus the infinitive.

bwari jono katala lazde = I saw John cutting the grass ....................... katala lazde is a saidau kaza ..... katala is a saidau baga

bwari lazde jwola kata = I saw the grass being cut ............................. jwola kata is a saidau kaza

bwari lazde jwola kata hí jono = I saw the grass being cut by John .... jwola kata hí jono is a saidau kaza

Note ... although the là suffix is probably connected to the second pilamo it should be recognized as a separate siffix here. If it was the pilamo we would have ... bwari lazde là jwòi kata

bwari lazde kataya = I saw the grass that has been cut

bwari lazde katawa = I saw grass that must be cut = I saw that the grass must be cut

lazde katawa bwari = I saw the grass that must be cut

bwari lazde nài r katawa

..

..... Making it flow

..

Grammar provides ways to make the stream of words coming out a speaker's mouth nice and smooth ... no lumpy bits.

Getting rid of the lumps entails dropping the elements that are already known ... these elements that are already uppermost in the mind. (De-lumping also involves inserting words that efficiently link to these elements that are already uppermost in the mind ... sometimes known as "anaphora". This aspect of de-lumping will be covered in the following section).

..

... Dropping

..

This section is about dropping known elements ... both arguments and person-tense markers.

A sentence [utterance = ???] is made up of one or more clauses [r-blocks]. Two r-blocks are separated by è or another particle. é is the most common particle for joining clauses and means "and then".

In béu the particle for joining nouns and adjectives is lé

In English "he eats cheese and nuts" could be analyzed as "he eats cheese and (he eats) nuts" with the bracketed part dropped. In béu this analysis is not available. The particle between the two nouns would be lé (ar perhaps if the speaker had added "nuts" on as an afterthought ... uwe "also" would come after "nuts" (a pause before) ). The particlle è would not be used. It only separated two clauses that have dissimilar verbs.

Now in English allows the dropping of an S or A argument in a sentence when this argument has already been established as the topic. béu is pretty much the same. When two clauses are joined certain arguments are dropped from the second clause. The béu rules for dropping arguments are not atypical of the worlds languages*. The rules are given below.

..

..

In the above "C1" stands for "the first clause" and "C2" stands for "the second clause". And also in béu it is possible to integrate the two clauses further ... if the two claues share a subject and all the tense/aspect/evidential of the two verbs match, then the second verb can take its i-form (and as the definition of a béu clause is "one r-block" ... the result should be considered ONE clause. The dropping of the subject in the second clause is more or less mandatory, it would sound quite strange to retain it. As for conflating the two verbs ... well it depends how tightly bound logically the two verbs are ...

..

..

Two examples are given above. The choice between conflated and not conflated depends upon the larger body of text that these examples are embedded in. But the relative likelyhood of conflation (over all situations) is given above. It can be seen that the more predictable second verb has a greater chance of being converted into its i-form. This makes sense as more unpredictable => more information. And we do not like to put to much information in one clause.

Examples are given below ...

1) The man hit the woman and then [the man] smashed her glasses. [ there are different objects ..... can be two clauses ]

2) The man awoke and then [the man] ate his breakfast. [ this would usually be conflated ]

3) The man drank all the beer and then [the man] slept. [ this would usually be conflated ]

4) The man coughed and then [the man] went to sleep. [ maybe two clauses ... no real logical tie between the two verbs ]

5) The man hit the woman and then [the man] was spat on. ... the C2 O argument can only be dropped if the C2 A argument is irrelevant ??? [ can not be conflated ... different subject ] .... to undergo ??

6) The man woke up and then [the man] was spat on. ... the C2 O argument can only be dropped if the C2 A argument is irrelevant ??? [ can not be conflated ... different subject ] .... to undergo ??

7) The man hit the woman. Then the woman shot the man.

8) The man hit the woman. Then the woman cried.

9) The thief robbed the girl. Then the pirate raped her.

Note ... For examples 5 & 6, the dropped arguments are counted as S arguments. In béu they are considered O arguments.

Note ... For examples 5 & 6, the A argument can be supplied in a hí phrase (similarly, in English the agent can be supplied by a "by" phrase)

Dropping arguments is appropriate when the to clauses are bound together in meaning (and when bound together in meaning, by iconicity, usually on the same tone contour).

The last three cases which could not drop any arguments, are felt to be, not so tightly bound together. It is no co-incidence, that these clause pairs are often given separate tone contours ... that is ... they are separate sentences.

..

... Linking back

..

A good example of a word that links back is badas "afterwards"*. It is derived from bada "after" plus the adverbial suffix -s.

Normally when you join to clauses the linking particle is è "and then". However if the second clause is an afterthought that comes after you have stopped speaking, you must use badas. This word is an adverb (has scope over the whole clause) and means "after" ... but after what ? The answer is the action already described in the first clause ... this information is still uppermost in everybody's mind and still very accessable. Alternatively there can be no first clause ... badas can appear after a long period of silence. In this case "the after what" refers to some action that is uppermost in everybody's mind although not recently spoken about**.

....................................................................................

jefias = since then ....... since < sið ðan [after that]

jenas = until then ...... until < (up to)/(as far as) x 2

*In English(well in my variety of English anyway, some from North East USA find (3) unacceptable and (1) marginal), there are three ways to that this anaphorical operation can happen.

(1) “John came. Afterwards Mary came” (2) “John came. After that Mary came” (3) “John came. After, Mary came”

In béu only construction (1) is acceptable ... i.e. with badas

**For example ... say you are a painter and decorator working with your helper at some sight. Now you both know that the next task will take around 15 minutes and it is a two man job. Your helper says he is gasping for a cigarette. To put him off for a bit, you can simply say badas

..

Now the five particles talked about in the previous section must always be followed by something appropriate. If they are not, they must change their form.

..

OK let us discuss this usage a bit. In English it is possible to say "We will do the paperwork after". Now the interlocarors must have some task (or tasks) in mind which they are going to do before the paperwork. In English this task is simply dropped ... it is part of the background. However in béu the particles feel wrong if they do not have appropriate words following, so the longer version is used.

Anaphor .... things whizzing around .... "mindwhiz" .... dropping and anaphora

It might be felt that the suffix is referring back some action that was mentioned before.

bada = after ...... badas = afterwards

kaca = before ... kacas = beforehand

ò is used to represent an person, mentioned before, and still current in everybody's mind.

ʃì is used to represent an object, mentioned before, and still current in everybody's mind.

só is used to represent an scenario, mentioned before, and still current in everybody's mind.

The above would be used in such sentences as ... "She acquiesced to return to Crosby's hotel room ... which was a very bad idea".

English is quite permissive as to what can be used for anaphora.

"That is good" or "This is good" can be about a situation [ they can also be about an object mentioned before as well ]

In béu "That is good" or "This is good" (when talking about a situation) => án rò bòi

"That is good" or "This is good" or "It is good" (when talking about an object) => dò r bòi

??? "it is good that he is coming back" .... "that he is coming back is good" is too front heavy .... What can béu use for "it" ?????? just miss it out "is good that ..... " ???

..

Four (five with nai.an ?) other particles also take -an. They are ...

| lau.an | to that degree |

| kai.an | like that |

| we.an | thus, so, in that way |

| sai.an | for that reason |

English uses that for anaphora in the above 4 examples.

All these words are overwhelmingly/always ? utterance final.

..

..... Ways to join clauses timewise

..

We will cover seven particles in this section ... jé kyù koca beda kogan began and jindu.

..

But first a bit about timekeeping in general ...

Below I have given a jekas. jekas can be translated as "date" or "time". A jekas can define a time from circa 200,000 years ago to 200,000 year in the future down to the nearest 50 second period. For example omba bene odaudai dimaku ?oli sunaba ajau is a jekas. It is analyzed below ...

..

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| omba | (komo/bene) | odaudai | dimaku | ?oli | sunaba | ajau |

..

1) ring/cycle/circle

2) (negative/positive) ... these can be dropped if it is known from context or from a tense affix, whether we are talking about the past or the future. By the way ... negative corresponds to the past.

3) "the number of the 128 year long cycle". odaudai = 55012 = 78010. As time zero in the béu calendar is 22 Dec 2083, we are talking roughly about a hundred thousand years in the future here.

4) "the particular year of the 128 cycle". dimaku means python and is the 100th year of the 128 year cycle.

5) "the particular sabata of the year" ... there are 5 sabata a (73 day long period) in one year ... ?oli pwè gú gamazu and yika

6) sunaba is the sixteenth day of the 73 day sabata ... [ In chewa, sabata means "week" ... and Yes, I know this is very unlikely to have Bantu provenance ]

7) "the particular fraction of the day that has past" ... ajau => 10012: 24 hours = 100012 : hence ajau = a twelfth of a day or 2 hours. As the day starts at 06:00, ajau corresponds to eight in the morning.

[ By the way ... if you put pluralize ajau you get ajau.a. This word corresponds to the time period between 08:00 and 10:00 ... ifau.a = 10:00 => 12:00 ... ibau.a = 12:00 => ... (well you get the idea)

..

Now a jekas can be put at the periphery of a clause to identify when an action is happening. This is what they are nearly always used for. However jekas are hardly ever given in full. For example it might be deemed sufficient just to give the time of the day. When time of the day occurs by itself it MUST be preceded by the particle jé.

| jene-s | d-o-r-e | jé | ajau | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jane-ERG | arrive-2SG-IND-PST | at | 08:00 |

=> Jane arrived at eight in the morning

Also it might be deemed sufficient just to give the day. It this case jé can be used. It is maybe used about 50% of the time that the day occurs alone or when the day occurs followed by the time of day.

| g-a-r-u | (jé) | geufa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| do-1SG-IND-FUT | on | the seventh day of the month |

=> I will do it on the seventh

..

| tomo-s | d-o-r-i | (jé) | geufa | ajau | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas-ERG | arrived-2SG-IND-PST | on | the seventh day of the month | at 08:00 |

=> Thomas arrived on the seventh day of the month at eight in the morning

Only in the three situations above do you get jé introducing a truncated jekas.

..

..

DAY TEN = the tenth day = 7 minutes into the day => jé always precedes the "hour numbers" (well if the name of the day kika exists it can be dropped)

falaja = afternoon : falajas = in the afternoon/every afternoon .... (jé) falaja = in the afternoon

yildos = morning : yildozas = in the morning/every morning ....... (jé) falaja = in the afternoon

jana (swahili) = yesterday : kojana = the day before yesterday :

kuzaza (zulu) = tomorrow : bezaza the day after tomorrow :

"longtime" súa / short-time gìa ..... uzuas = soon

This time system is sufficient for all of human history. Of course to talk about cosmology, or even geology, some sort of extended system is needed.

To show "where" an action takes place, béu places ?é before the "where".

In a similar manner, to show when an action takes place, béu places jé before the "when". For example ...

..

..

...

As well as defining "when" absolutely using these special time adverbs, it can be defined relative to some other "action". When this happens the phrase describing this other action is equivalent to a time adverb ... called a time adverb phrase. A time adverb phrase is a dependent clause (called an under clause in béu). It is shown in red in the diagram below. The main clause is shown in yellow.

Tha arrow is the arrow of time* ... with the past to the left (komo), and the future to the right (bene).

I have given events wavey borders to represent "not so well defined". So, for example, on the top diagram ... the main clause action could start before the under clause action ... it could also outlast the under clause action ... the important thing is that for a substantial amount of time, the two actions were going on at the same time.

In the bottom four examples I have made the under clause actions very short. This is for illustration purposes only. The under clause actions can actually have any length ... depend on the verb/situation.

Now these five examples show how two clauses can be joined in a timewise fashion. The béu rules are quite similar to English. That is ...

A) the under clause must be introduced with one of these 6 particles.

B) we can have main clause and then the under clause ... or the other way around.

Here are examples to illustrate the 5 examples above ...

..

1) kyù = while, as ........ ( note to self : jé is definite : kyù not so ... =if ?? )

pás pintu saikaru kyù gís pazba saikiru = "I will paint the door, while you paint the table"

*kyù gís pazba saikiru_pás pintu saikaru = "while you paint the table, I will paint the door" ... this construction is not allowed

kyù saiko pazba_gís huʒiri = "while painting the table, you smoked"

..

2) koca = before

pazba saikaru koca pintu (saikaru) = "I will paint the table before (I will paint) the door"

*koca pintu saikaru_pazba saikaru = "before I paint the door, I will paint the table" ... this construction is not allowed

koca saiko pintu_pás pazba saikaru = "before painting the door, I will paint the table"

..

3) beda = after

pintu saikaru beda pazba (saikaru) = "I will paint the door after (I will paint) the table"

*beda pazba saikaru_pintu saikaru = "before I paint the door, I will paint the table" ... this construction is not allowed

beda saiko pazba_pás pintu saikaru = "after painting the table, I will paint the door"

..

If you wanted to emphasize that the first action will continue until the second action you would use ...

4) kogan = until

gís huʒiri kogan dare saiko pazba = "you smoked until I started to paint the table"

*kogan dare saiko pazba_gís huʒiri = "until I started to paint the table, you smoked" ... this construction is not allowed

kogan día saiko pazba_gís huʒiri = "until starting to paint the table, you smoked"

..

If you wanted to emphasize that the first action has been continuing all the time since the second action you would use ...

5) began = since

gís ʔès huʒira figo care saiko pazba = "you have smoked since I stopped painting the table"

| gí-s | ʔès | huʒ-i-r-a | began | c-a-r-e | saiko | pazba |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| you-ERG | already | smoke-2S-IND-PRES | since | stop-1S-IND-PAST | painting | table |

==> "you have smoked since I stopped painting the table"

*began care saiko pazba_gís huʒira = "since I stopped painting the table you have smoked" ... this construction is not allowed

began cùa saiko pazba_gís ʔès huʒira = "since stopping painting the table, you have smoked" ... [By the way ... began ìa saiko pazba_gís ʔès huʒira = "since finishing painting the table, you have smoked" ]

..

There is one added complication in the above scheme ... if the intersect time of the two actions is in the future, then jindu (<jín "a moment" + dù "exact") can be used instead of began.

..

..

Now what about the case where one clause has been spoken, then after half second or so, it comes into the speakers head, that the other clause is also of interest to the hearer. Well in these cases, one of the below constructions must introduce the "afterthought".

..

..

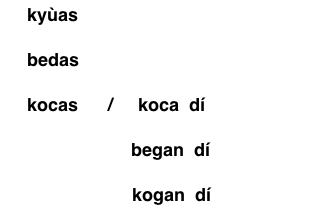

The s or as suffix is the adverbial marker. And the adverbials kyùas, bedas, kocas make a connection to the clause just spoken. They are anaphora. All the elements of the last clause are still whirring around the brain : they are easily accessible. And these words make a link to the "just spoken clause", to be specific, that make a link to the time of action of the "just spoken clause". Usually a pause occurs after these words ... maybe to give the hearer time to absorb the fact that a "link" has just been made.

Notice that only kyù can take the adverbial marker ... jé never does. Also jindu never comes into this scheme.

The dí is the proximal determiner (i.e. "this"). In béu dí can link to the entire "just spoken clause". [ Notice that English does something similar with "that" and "then" ]

Now how to explain the above diagram. Well some believe that for an adverbial to exits, it must be quite common. That is kogan and began as afterthough introducers are quite uncommon, hence the phrases kogan dí and and began dí are used as opposed to *koganas or *beganas. Notice that koca can exist as an afterthought indroducer in the form kocas or koca dí. It is not known why the terms *kyù dí and *beda dí are not allowed.

..

*The organization of the Chinese writting system seems to have affected the language itself. The primary writing direction was top_to_bottom so of course the calendar was written top_to_bottom as well. From that "above" got associated with "the past" and "below got associated with "the future". A similar thing happened in béu. The practitioners of béu are above all engineers and the algebraic convention of having time along the horizontal axis has affected the language somewhat ...

..

..... Ways to join clauses non-timewise

..

Another particle used for combining clauses is tè "but". This is used when C2 is "contrary to expectation".

??? "but" can sometimes come before nouns in English. For example ... "all but me" .... in béu' we use u?u ???

There are also some phrases with more "sound.weight" that have the exact same meaning as tè.

?? Well this is the more neutral particle (the particle plí can also be used ??

??? sé dù/è dù : these mean that action B follows on immediately from action A.

??? sé kyude/è kyude : these mean that action B follows action A but not necessarily immediate. Sometimes sé è are dropped.

??? kyugo : this means that action A and B happen at the same time. Usually we have different actors in the two clauses, but not always.

..

*There are other possible rules though. RMW Dixon uncovered the very interesting Dyirbal system.

..

pleulas and then

unya

badas afterwards

jį gò

ji?is ..

huzu = to smoke

koʔia = to cough

solbe = to drink

caume = medicine

Notes on grammar .... If you have two clauses, the particle must come between them : the element containing only infinitives (for example ... figo ìa saiko pazba) is not a clause. I call it a "clause adjunct" or "adverbial phrase" [I should pick one term] : for the examples above containing a clause adjunct, note that only the main clause has a subject : notice that what is marked by the perfect in English is marked by ʔès "already" in béu. In English the perfect has 3 functions ... the resultative, the experiential and the so called universal which indicates that activity has been going on for sometime and still is. In béu the perfect marker was derived from a verb meaning "finish" ... a marker derived from this source can scarcely be expected to have this "universal" function.

Also note ... cùa jì gò saiko pazba = "to leave in order to paint the table" ... In English you can drop "in order" to get "to leave to paint the table". In béu this would result in "to stop painting the table" ... never leave out jì gò.

Usually this type of clause adjunct does not express a subject ... but sometimes it can ... the subject is places after the word sàin "reason, cause, origin" and sàin comes after the object (if there is one) and the object comes after maŋga. The only element allowed to the left of maŋga is the negative jù. For example ....

timpa jene sàin jono r kéu = John's hitting of Jane was bad .... [maybe hí is better than sàin ???]

There are five particles used to introduce these time adverb phrases. Each of these particles defines a different time relationship between the main action and the under action.

Note ... Both the main action and the under action can vary considerably in length. In the above diagrams I give what I consider typical time lengths.

Note ... In English "since" can only be used for an under clause that occurs in the past. For example ...

jefi jono joru_ufan rù bòi = After John goes, everything will be fine

The literal translation of the above is "since John will go, everything will be good" ... In English "since" has taken on a second meaning*. In béu, jefi has no such secondary meaning and it is perfectly to use jefi with a clause set in the future. [In the chart I specify a NOW ... this is really to signify the situation for typical usuage of the English word. The NOW is not relevant to the béu usuage]

..

*GIVE THAT EXAMPLE FROM DEUTSCHER'S BOOK.

..

The usuage of these five particles is quite straightforward. However there is one little quirk that should be pointed out. For example ...

jono liga ko?ori jén ós solbori moze = John was coughing until he drank some water ..... ko?ia = to cough

Now the above can be recast ...

John was coughing until the drinking of water by him => jono liga ko?ori jén solbe moze hí ò

This can be futher cut ...

John was coughing until the drinking of water => jono liga ko?ori jén solbe moze

And further cut ...

John was coughing until drinking => jono liga ko?ori solben .... Not *jono liga ko?ori jén solbe

When the verb-noun is only one word it will take the suffix -n instead of the particle jén

In a similar way, when the verb-noun is only one word it will take the suffix -fi instead of the particle jefi. For example ...

John has been coughing since he smoked a cigarette => jono ko?ora jefi ós huzore ʃigita ... huzu = to smoke, to suck

John has been coughing since smoking => jono ko?ora huzufi .... Not *jono ko?ora jefi huzu

..

For beda and koca, when the time between the two events are stated ... it comes immediately after bade or koca. For example ...

beda odai yanfa jene fori = After five minutes Jane left (is féu Ø or H ?) .... [ yanfa = 5 seconds, odai = 5012 = 6010 ... so the translation is 100% accurate ]

..

..

7) jì gò = "in order that" "so" "so that"

It shows that the first action was done in order to bring about the second action/state. The particle is always between the clauses.

jonos jenen toili nori jì gò ós ò klór = John gave Jane a book in order that she would like him.

The second clause is the <purpose> of the first clause .... jonos jenen toili nori is a clause : ós ò klór is a clause : jì gò ós ò klór is an adverbial adjunct

The second clause always has the aortist tense form in this construction ... actually the gò jì makes the second verb sort of irrealis.

..

Notice that if the second clause was replaced by a NP ... jì "for" or "for the benefit of" would be the particle used.

If both clauses have the same subject, then the second one usually becomes an "infinitive adverbial adjunct, and the particle jì is used.

toili mapari jì kludau ʃila = I opened the book in order to write in it

tarye dían jì twá gì = I came here (in order) to meet you

Occasionally you can have this construction where the object of the first clause is the subject of the second clause ...

pà babas gaidoryə dían twá gì = My father brought me here to meet you

From the underlying semantics of the above, it is pretty obvious that "the father" was not intent in "meeting you"

[ Note to self ..... In English "in order to" is only used with same subject constructions .... interesting ]

..

8) plùa = "therefore" "so" "hence"

It shows that a second clause follows on logically from the first clause. The particle is always between the clauses.

ò klár plùa òn nari toili = I like her so I gave her a book

The second clause is the <result> of the first clause .... No adverbial adjuncts in this construction

..

9) sài gò = "because" "as" "since"

It shows that the second state/action is a consequence of the first action/state. The particle is always between the clauses.

jenes jono klór sài gò òn nori toili = Jane likes John because he gave her a book

The second clause is the <reason> for the first clause .... jenes jono klór is a clause : òn nori toili is a clause : sài gò òn nori toili is a adverbial adjunct

..

Notice that if the second clause was replaced by a NP ... sài "because of" would be the particle used.

..

10) dà = where

pà twá dà twaire yildos = meet me where we met in the morning

pà twá is a clause ... twaire yildos is a clause ... dà twaire yildos is an adverbial adjuct .... "adjunct" is something that can be added to a clause

..

11) kyù = when

kyù twaru jene òn fyaru = When I see Jane I will tell her.

12) tà = if (hypothetical)

13) ʔáu gò = if (counterfactual) ... maybe equivalent to "suppose, imagine, assume".

Actually the above 3 form a sort of continuum as regard to the likelihood of the matrix verb actually occurring. We could say ...

kyù covers the likelihood range of 100 % => 90 % : tà from 90 % => 10 % : ʔáu gò 10 % => zilch

All three are used with pretty much the same frequency in béu.

Actually the context determines to a large extent likelihood of the matrix verb actually occurring in English (and in most languages). For example ... "when pigs can fly"

..

Note on English .... English uses "if" for both hypothetical and counterfactual. Things are a bit twisted in the English usuage.

"If it rained tomorrow, people would dance in the street." .... notice that the conditional clause has a past tense verb, but is actually talking about the weather

"If it had rained yesterday, people would have dance in the street." .... and to get a counterfactual "past tense meaning", we actually have to use the past perfect form.

..

14) jindu = as soon as

15) tè gò = unless .... [the above 5 conjunctions .... should they use gò to separate the clauses : should they use plùa to separate the clauses ???) ..

16) dó = "although" "though" "even if"

This conjunction introducing a clause denoting a circumstance that might be expected to preclude the action of the main clause, but does not. It has a more emphatic variation .... ?emodo

Notice that dó and plàu are related. Any pair of clauses joined by plàu can be transformed into a pair of clauses joined by dó ...

a) negating the first clause

b) swapping the clause positions

c) get rid of plùa and insert dó between the clauses.

He is tall so he is good at baskerball

He is good at basket ball although he is short

..

17) kài = "as", "like", "the way"

kài is sufficient for joining clause (kài gò is never seen). If you look back on the chart at Ch2.11.1 you see that kài is an introductory particle indicating "manner". Manner means some action and action means a clause.

"I was never allowed to do things as I wanted to do them"

..

..... Word building

..

Many words in béu are constructed from amalgamating two basic words. The constructed word is non-basic semantically ... maybe one of the concepts needed for a particular field of study.

..

In béu when 2 nouns are come together the second noun qualifies the first. For example ...

toili nandau (literally "book" "word") ... the thing being talk about is "book" and "word" is an attribute of "book".

Now the person who first thought of the idea of compiling a list of words along with their meaning would have called this idea toili nandau.

However over the years as the concept toili nandau became more and more common, toili nandau would have morphed into nandəli.

Often when this process happens the resulting construction has a narrower meaning than the original two word phrase.

There are 4 steps in this word building process ...

1) Swap positions : toili nandau => nandau toili

2) Delete syllable : nandau toili => nandau li

3) Vowel becomes schwa : nandau li => nandə li

4) Merge the components : nandə li => nandəli

..

The above example is for 2 non-monosyllabic words. In the vast majority of constructed words the contributing words are polysyllables.

The process is slightly different when a contributing word is a monosyllabic. First we look at the case when the main word is a monosyllable ...

wé deuta (literally "manner soldier")

1) Swap positions : wé deuta => *deuta wé ........ there is no step 2

3) Vowel becomes schwa : *deuta wé => *deutɘ wé

4) Merge the components : *deutə wé => deutəwe

..

And the case when the attribute is a monosyllable ...

nandau sài (literally "word colour")

1) Swap positions : *sài nandau

2) Delete syllable : *sài dau .......................................... there is no step 3

4) Merge the components : *sài dau => saidau

..

And another case when the attribute is a monosyllable ...

ifan kwò (literally "double wheel")

Note .. the head is the notion of "duality", Also kwò "wheel" is related to "kwèu "to turn"

1) Swap positions : *kwò ifan

2) Delete syllable : *kwò fan .......................................... there is no step 3

4) Merge the components : *kwò fan => kwofan

..

And the case when the attribute ends in a consonant ...

megau peugan ... "body of knowledge" "society"

1) Swap positions : *peugan megau

2) Delete syllable : *peugan gau

3) Delete the coda and neutralize the vowel :*peugan gau => *peugə gau

4) Merge the components :*peugə gau => peugəgau

..

And the case when the main word has a double consonant before the end vowel ...

kanfai gozo ... merchant of fruit

1) Swap positions : *gozo kanfai

2) Delete syllable : *gozo fai ............................. Note kan is deletes, not just ka

3) Vowel before the final consonant becomes schwa :*gozo fai => *gozə fai

4) Merge the components :*gozə fai => gozəfai

..

And here are a few examples to demonstrate the semantic range that this technique can encompass ...

laŋku = shadow, reflection

miaka = echo, response, effect

Which produce miakəka meaning "subtle influence" or "to subtly influence"

..

sword.spear => weaponry ... shield.helmet => armour, protection ... knife.fork => cuttlery ... table.chair => furniture

There are no cases where both contributing words are monosyllables.

As with the schwa-form and the i-form verbs ... the schwa is represented by cross.

When spelling words out, this cross is pronounced as jía ... meaning "link".

Notice that when you hear nandəli, deutəwe or peugəgau you know that they are a non-basic words (because of the schwa).

This method of word building is only used for nouns.

..

..... Bicycle plus

..

Above I explained the word for bicycle ...

There are a few more words that follow the same pattern ....

kwoban = tricycle

poməfan = a biped ............................... poma "leg"

poməgan = a quadruped

poməlan = an insect

poməzan = an spider ............................ note béu is one of the few languages in the world to give the octopus a unique name.

nodəban = a threeway intersection ....... node "node"

nodəgan = a fourway intersection

nodədan = a fiveway intersection

And so on ...

The regular shapes in 2 dimensions ...

?aban = a triangle

?agan = a quadrilateral

?adan = a pentagon

?alan = a hexagon

And so on ...

The 5 regular shapes in 3 dimensions ...

ʔaugan = a tetrahedron

ʔaulan = a cube

ʔauzan = an octahedron

ʔaujaun = a dodecahedron

ʔaujauzan = an icosahedron

The 6 regular shapes in 4 dimensions ...

ʔaidan = a 5-cell

ʔaizan = an 8-cell

ʔaijaugan = a 16-cell

ʔaifain = a 24-cell

ʔaipain = 120-cell

ʔaigaufain = 600-cell

..

..... Set Phrases

..

If you meet somebody who you have not met for sometime you say gò yír fales "may you have peace".

If you meet some people who you have not met for sometime you say gò yér fales "may you have peace"

On taking your leave of somebody who you have not met for sometime you say gò nela r gimau "may the blue sky be above you"

On taking your leave of somebody who you have not met for sometime you say gò nela r jemau "may the blue sky be above you"

If you pass somebody in the street or you meet your workmates for the first time in the morning fales is sufficient. If you say gò yír fales it typically means that you are going to have a ten minute (at least) chat.

..

There are some set phrases ... these are not a million miles from interjections

Also there two phrases { "j" and "k" } which could be considered interjections. They have the intonation pattern of a single word.

(A) yuajiswe.iʃʃ which expresses consternation and/or grief. In about 30% of cases it is shortened to swe.iʃʃ only.

It means ... (say "iʃʃ" for us)

(B) hambətunmazore which expresses great joy. In about 70% of cases it is shortened to hambətun only.

It means ... (the gates to heaven have opened)

(C) And finally when somebody is telling a story or giving detailed instructions, you might say plirai at suitable intervals. This is simply a contraction of plìr ʔai? ... "do you follow ?"

(D) ... OK, we are scrapping the bottom of the barrel here. Not an exclamation in béu but maybe an exclamation in another language ... hù nén.

It expresses sudden consternation/dismay, equivalent to ... WHAT !!

(E) kè kè = "sorry" or "excuse me" ... Related to the word kelpa meaning "to apologize".

(F) sè sè = "thank you" ... Related to the word senda meaning "to thank".

..

... A discussion on Complement Clauses and Variable Clauses

We live in a world that has an independent reality. For example ... If nobody is looking at ... say A TREE, that TREE continues to exist. If nobody is thinking about this TREE, this TREE continues to exist. Even if no sentient being has any knowledge whatsoever of this TREE, this TREE continues to exist ... in fact this TREE is totally indifferent as to whether it is being looked at or thought about ... this TREE is totally indifferent as to whether it has EVER been looked at or thought about.

I BELIEVE THE ABOVE IS SELF-EVIDENT.

The philosopher George Berkeley (1685–1753) questioned the above (or at least he is reported to have questioned the above).

But in reality ... the entire Universe exists independently of any observers. In actual fact EVERY ADULT HUMAN carries an (imperfect) model of his environment in his mind and uses this model to plan his actions. The main reason HUMANS have been so successful compared to other animals is that we have a more complete model than ... say ... our primate cousins. The reason that out model is good is that we have LANGUAGE and so get information from our fellows. Probably the building of this MODEL and LANGUAGE were co-developements and could well be reflected in the size of the HUMAN BRAIN over the last few million years. I believe that this MODEL and LANGUAGE are intertwined and hence I don't think it is a good idea to consider either in isolation.

Now usually when we communicate ... we just talk about reality. For example ... JOHN IS TALL. We do not acknowledge the actual more complicated situation ... IN MY WORLD MODEL, JOHN IS TALL.

But sometimes we do .... usually when we are talking about activities related to our mind ... like "thinking", "knowing" ... disseminating knowledge to our fellows "telling", "saying" ... gathering knowledge first hand "seeing", "hearing" ... trying to gather knowlege from our fellows "asking". All these bracketed verbs can take what are called complement clauses. When you see a complement clause you are seeing an admission that what we are talking about is not in fact REALITY, but some MODEL of REALITY. Maybe you could say that it is an admission that we are using META-DATA rather than DATA.

The following might illuminate a bit. What is on the white background is REALITY. What is on a black background is part of a MIND MODEL . The script on an orange background is a speach act appropriate for the situation shown. The first panel is the way that we normally speak ... that is REALITY is presented directly with no referrence to any MIND MODEL.

Now it seems that most languages have at least one way of bracketing off the META-DATA from DATA.

..

From now on Complement Clauses => CC's

Dixon reckons there are 7 different types of CC in English ...

(1) John said that you are an idiot.

(2) John knowswhat you did last night.

(3) She mentioned John hitting the dog.

(4) It's bad for Jane to waste all her money.

(5) She declared John to be an idiot.

(6) I told her where to park her car.

(7) She dissuaded him from going

Actually I would only consider (1) and (2) to be CC ... I would say (3) to (7) to contain different types of "Infinitive Phrases" ( Infinitive Phrases => IP )

Take example 7 for example ... how can you parse that ? There should be nothing underlined there ... "dissuade" is a 3-part verb ... "from" is a preposition that defines the roll of the least pertinant part ... "she dissuaded him from going" really can not be broken up into smaller parts.

(1) The word "that" functions as what is called a "deictic noun" ia in "Did you see that ? It is reasonable to assume that "John said that you are an idiot" <= "John said that" ... "you are an idiot" with "that" referring to the second clause. However over time this sentence type got more integrated and (along with a change in intonation) "that you are an idiot" got re-analized as an embedded clause.

(2) This type of construction is very interesting. The embedded clause what you did last night is equivalent to a variable in mathematics (usually represented by X, Y or Z). And just as in mathematics the use of variables allows you to you to manipulate concepts without knowing there exact value, this "what" type of construction allows to to say things that ... either (a) you don't know .... or (b) are to unwieldy to say. For example the guy that spoke "John knowswhat you did last night" does not have to have this knowledge himself (alternatively he could have this knowledge ... but maybe if ten things were done last night ... well it is just too time consumming to enumerate them all).

This type of construction represents a "indefinite" ....

(2a) She asked what did you eat ................................... indefinite thing

(2b) She asked who ate the sandwich ........................... indefinite person

(2c) She asked where did you eat the sandwich ........... indefinite place

(2d) She asked when did you eat last ........................... indefinite time

(2e) She asked whose sandwich did you eat ................ indefinite owner (person)

(2f) She asked which restaurant did we eat at ............. indefinite X out of all the X present/possible/pertinant. X represents a "unit" rather than a "type".

(2g) She asked how we got to the restaurant .............. indefinite manner

(2h) She asked why we didn't go to her restaurant ..... indefinite reason ............. 8 question words in all in English

All 8 function as Question Words.

All 8 function as Complementers ... well all languages have verbs which introduce direct speech (page 36 of A Semantic Approach to English Grammar). And as all 8 are used in direct speech (i.e. QW's) it is not surprising that they have worked their way into complementizer position. Note that the above CC do not have direct speech. Well sometimes it is hard to determine if they are direct or indirect ... you must know the background to know ???

..

..

Note that the QUESTION and the VARIABLE CLAUSE have different forms because of the English rule that you swap the position of the subject and the first word in the verb phrase in a question. However for (e) and (f) this swapping of positions is not possible as "whose" and "which" are constituents of NP as opposed to constituents of a verb phrase.

It is (probably) for this reason that the element -"ever" is required appended to these to forms. In fact the element -"ever" can be appended to the "wh" word in any variable clause. It increases the "indefiniteness" feeling.

From this analysis it seems like we should write "whose" as "who's" ... that is ... there is no independent word "whose".

As to "why" is not a variable clause ... well to me "why I let you go ..." sounds infelicitous rather than a big NO NO. I judge it to be wrong but not by much. Probably it is illegal because of the prevalence of the conjunction "because" ... which makes a variable clause about reason ... unnecessary.

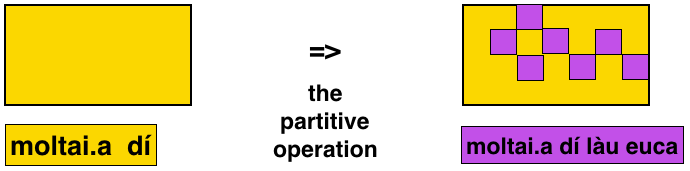

... Extending a NP using the partitive ..."làu"

..

In section 2.7 we analyzed the the different components that can go into seŋko kaza or the noun phrase if you will. Here we will go into it in a bit more detail. It will be seen that there is a bit of "internal structure" ... a bit of complexity that is not obvious upon first blush.

..

.. Sets and subsets

..

Nearly every seŋko occurs in multitudes. OK, there are a few counter examples, such as kòi "sun" but for the most part they occur in multitudes. When we talk about any plurality of these nouns it is possible to change the scope of the set under discussion ... it as if we can zoom in and zoom out and this ability to "zoom" is defined by grammar (what else).

Let as take the noun moltai "doctor" to demonstrate this. Below ... represented by the orange area is all the doctors in the world (and also presumable the Universe*).

*This "zooming" idea is not fully air-tight, there is a bit of fuzzyness about it ... hence the inclusion of "presumably".

..

The above is as far as we can zoom out. Call the total orange area the "u* set". This scope is appropriate for generic pronouncements. Such as ...

moltai.a súr jini = "doctors are clever"

* u for universal.

..

OK ... now lets zoom in a bit. To zoom in we need to take in or give out some narrative. So now we hear the following ....

Next week British junior doctors will withhold many services in protest against the long hour expected of them

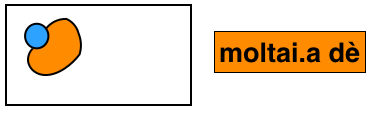

OK ... after hearing that ... and if the NP "these doctors" moltai.a dí is mentioned and commented on it becomes fixed in the mind of all the interlocators.

moltai.a dí is represented by the orange area in the Venn diagram below.

OK ... lets hear another bit of narrative and change the "set" of doctors under consideration again. The narrative is ...

Much to the disgruntlement of the senior doctors who will have a hard week ahead of them making up for the short fall.

OK ... after hearing that ... and if the NP "those doctors*" moltai.a dè is mentioned and commented on it becomes fixed in the mind of all the interlocators.

moltai.a dè is represented by the orange area in the Venn diagram below.

OK ... after hearing that, the NP "those doctors*" moltai.a dè is represented by the orange area in the Venn diagram below.

* This is presuming that the NP moltai.a dí was actually talked about after the first narrative. If not ... then the NP moltai.a dí would be used to refer to the senior doctors. So it is like the particles dí and dè are letting us keep track of two "sets" of doctors at the same time. That is ... the NP's moltai.a dí and moltai.a dè have been set up in the minds of all interlocators to refer to two different sets. The second NP ( moltai.a dè ) only exists as a sort of contradistinction to the initial NP moltai.a dí .

OK ... this is as far as we can go with this example. I believe if you add the set "senior" doctors to the set "junior" doctors you have a set identical to the "set" doctors (However I could be wrong about this)

..

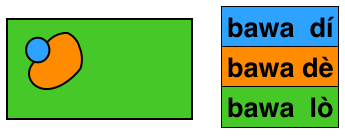

Lets change the example to take this idea further. Let us take bawa "men" for our noun. OK assume some narrative was given, and then bawa dí was mentioned to cement it into everybody's mind.

Then more narrative was given (defining a further subset) and bawa dé was mentioned to cement it into everybody's mind. A further NP can be used to refer to all bawa outside the first two sets. This NP is bawa lò "other men"

Actually bawa lò is usually used just one ... the set referred to as bawa lò are hardly ever kept in anybody's mind for more than a few seconds. In actual fact the first two terms don't usually persist long in a discourse either. We are continually zooming in ... zooming out ... changing our perspective.

..

.. The extended NP

..

When we were talking about how the NP was built up ( chapter 2.7 ) we mentioned the "numerative slot" that comes just before the head. We said that in this slot we can have either a "numerative" or a "selective". In this section we will discuss how these two classes of words interact with the singularity/plurality of the head noun. Also we will introduce a construction called "the extended NP" which gives a "partitive" meaning.

..

| 1 | jù moltai dí... | no doctor here | moltai.a dí làu jù... | none of these doctors |

| 2 | ʔà moltai dí... | one doctor here | moltai.a dí làu ʔà... | one of these doctors |

| 3 | hói moltai dí... | two doctors here | moltai.a dí làu hói... | two of these doctors |

| 4 | léu moltai dí... | three doctors here | moltai.a dí làu léu... | three of these doctors |

| 5 | iyo moltai dí... | a few doctors here | moltai.a dí làu iyo... | few of these doctors |