Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun: Difference between revisions

| Line 626: | Line 626: | ||

.. | .. | ||

== ... Questions== | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The 9 Question Words=== | |||

.. | |||

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 8 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "whose", "where", "when", "how" and "why". | |||

Note ... there was alsp a "whom" until quite recently. | |||

These are the most profound words in the English language. | |||

However these question words have over the mellenia been sequestered to support other functions. For example "who" can be used to .... | |||

1) Solicit a response in the form of a persons identity | |||

2) As a relativizer particle ... for example ... "The man who kicked the dog" | |||

3) As a complement clause particle ... for example ... "She asked who had kicked the dog" | |||

4) In the compound "whoever" which is an indefinite pronoun. | |||

Only in the first example is "who" asking a question. | |||

.. | |||

'''béu''' has 10 question words ... | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''dá''' | |||

|align=center| where | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kyú''' | |||

|align=center| when | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''nén nós''' | |||

|align=center| what | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''mín mís''' | |||

|align=center| who | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''sái''' | |||

|align=center| "why" | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kái''' | |||

|align=center| "what kind of" | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''láu''' | |||

|align=center| "how much" or "how many" | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''nái''' | |||

|align=center| which | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''ʔala''' | |||

|align=center| which | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''ʔai?''' | |||

|align=center| "solicits a yes/no response" | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

If you hear any of these words you know you are being solicited for some information. That is these words have no other function apart from asking questions. | |||

.. | |||

'''nós''' and '''mís''' are the ergative equivalents to '''nén''' and '''mín''' (the unmarked words) | |||

English is among the 1/3 of world languages which fronts a question word. I guess '''béu''' would be considered a content-question-word-fronter as well. | |||

'''dá kyú nén nós mín''' and '''mís''' are always sentence initial. (but '''pilana''' are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.) | |||

'''kái láu''' and '''nái''' are usually found in a NP. These NP's are always made sentence initial. ( '''kái''' and '''nái''' appearing after the head, '''láu''' before. ) | |||

Here are some examples of these words in action ... | |||

Statement ... '''bàus glán nori alha''' = the man gave the woman flowers | |||

Question 1 ... '''mís glán nori alha''' = who gave the woman flowers ? | |||

Question 2 ... '''í mín bàus nori alha''' = the man gave flowers to who ? | |||

Question 3 ... '''nén bàus glán nori''' = what did the man give the woman ? | |||

Question 4 ... '''í glá nái bàus nori alha''' = the man gave the flowers to which woman ? | |||

Question 5 ... '''á bàu nái glán nori alha''' = which man gave the woman flowers ? | |||

Question 6 ... '''alha kái bàus glán nori''' = what type of flowers did the man give the woman ? | |||

Question 7 ... '''láu alha bàus glán nori''' = how many flowers did the man give the woman | |||

Question 8 ... '''bàus glán nori alha ʔala cokolate''' = Did the man gave the woman flowers or chocolate ? | |||

Question 9 ... '''bàus glán nori alha ʔai?''' = Did the man gave the woman flowers ? | |||

.. | |||

"why" is expressed as '''nenji''' which means "what for" (by the normal '''pilana''' rules, it should be '''jì nén'''. However '''jì nén''' is never seen ... always '''nenji''') | |||

"how" is expressed as '''wé nái''' which means "which way" or "which manner" | |||

.. | |||

=== ... Polar Questions and the focus particle=== | |||

.. | |||

A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no". | |||

To turn a normal statement into a polar question the particle '''ʔai?''' is stuck on at the very end. | |||

It has its own symbol (and I transcribe it as '''ʔai?''') because it possesses its own tone contour. | |||

I have mentioned this particle in chapter 1 (if you look back you can see its exact tone contour). Here is its symbol again ... [[Image:TW_399.png]] | |||

And here is an example of it in action ... | |||

[[Image:TW_492.png]] ... '''jono jaŋkori ʔai?''' = Did John run ? | |||

.. | |||

'''ʔai?''' is neutral as to the response expected ... well at least in positive questions. | |||

To answer a positive question you answer '''ʔaiwa''' "yes" or '''aiya''' "no" (of course if "yes" or "no" are not adequate, you can digress ... the same as any language). | |||

Here is an example of a positive question ... | |||

'''glá r hauʔe ʔai?''' = Is the woman beautiful ? | |||

If she is beautiful you answer '''ʔaiwa''', if not you answer '''aiya'''<sup>*</sup>. | |||

.. | |||

To answer a negative question it is not so simple. '''ʔaiwa''' and '''aiya''' are deemed insufficient to answer a negative question on their own. For example ... | |||

'''glá bù r hauʔe ʔai?''' = Is the woman not beautiful ? | |||

If she is not beautiful, you should answer '''bù hauʔe'''<sup>**</sup>, if she is you can answer either '''hù hauʔe''' or '''glá r hauʔe''' | |||

I guess a negative question expects a negative answer, so a positive answer must be quite accoustically prominent (that is a short answer ("yes" or "no") is not enough) | |||

.. | |||

You will have noticed '''hù''' in the above example. This is the focus particle. It has a number of uses. When you want to emphasis one word in a clause, you would stick '''hù''' in front of it<sup>***</sup>. | |||

Another use for '''hù''' is when hailing somebody .... '''hù jono''' = Hey Johnny | |||

You can also stick it in front of someone's name when you are talking to them. However it is not a "vocative case" exactly. Well for one thing it is never mandatory. When used the speaker is gently chiding the listener : he is saying, something like ... the view you have is unique/unreasonable or the act you have done is unique/unreasonable. When I say unique I mean "only the listener" hold these views : the listener's views/actions are a bit strange. | |||

When stuck in front of a non-multi-syllable verb you get an imperative. For example ... '''hù nyáu''' = Go home | |||

'''hù''' can also be used to highlight one element is a statement or polar question. For example ... | |||

Statement ... '''bàus glán nori alha''' = the man gave flowers to the woman | |||

Focused statement ... '''bàus hù glán nori alha''' = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.<sup>****</sup> | |||

Unfocused question ... '''bàus glán nori alha ʔai?''' = Did the man give flowers to the woman ? | |||

Focused statement ... '''bàus hù glán nori alha ʔai?''' = It is to the woman that the man gave flowers ? | |||

.. | |||

Any argument can be focused in this way. | |||

.. | |||

<sup>*</sup>These words have a unique tone contour as well ... at least when spoken in isolation. I suppose I should have given these two words a symbol each ... if I wanted to be consistent. | |||

<sup>**</sup>Mmm ... maybe you could answer '''ʔaiwa''' here ... but a bit unusual ... not entirely felicitous. | |||

<sup>***</sup>In English, when you want to emphasis a word, you make it more accoustically prominent : you don't rush over it but give it a very careful articulation. This is iconic and I guess all languages do the same. It is a pity that .....there is no easy way to represent this in the English orthography apart from increasing the font size or adding exclamation marks. | |||

<sup>****</sup>English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to an element in a clause. | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The Generic noun equivalents=== | |||

.. | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''dà''' | |||

|align=center| place | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kyù''' | |||

|align=center| occasion | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''nèn nòs''' | |||

|align=center| thing | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''mìn mìs''' | |||

|align=center| person | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| '''kài''' | |||

|align=center| kind, type, sort | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| '''làu''' | |||

|align=center| amount | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The Relativizer=== | |||

.. | |||

In English, one of the functions of "who" is as a relativizer ... a particle that introduced a relative clause. For example .... | |||

"The man who ate the chicken got sick" | |||

Also in English, one of the functions of "that" is as a relativizer. For example .... | |||

"The chicken that was eaten must have been off" | |||

.. | |||

In '''béu''' there is only one relativizer ... '''nài'''. For example ... | |||

'''glà nài bàus timpori_sòr hauʔe''' = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful. | |||

.. | |||

'''nài''' takes case affixes the same way that a normal noun would. For example ... | |||

pi ... the basket '''naipi''' the cat shat was cleaned by John. | |||

la ... the chair '''naila''' you are sitting was built by my grandfather. | |||

mau | |||

goi | |||

ce | |||

dua | |||

bene | |||

komo | |||

tu ... '''báu naitu ò''' is going to market is her husband = the man with which she is going to town is her husband ... '''kli.o naitu''' he severed the branch is rusty | |||

ji ... The old woman '''naiji''' I deliver the newspaper, has died. | |||

-s ... '''báu nàis timpori glá_sòr ʔaiho''' = The man that hit the woman is ugly. | |||

wo ... The boy '''naiwo''' they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand. | |||

-n ... the woman '''nàin''' I told the secret, took it to her grave. | |||

fi ... the town '''naifi''' she has come is the biggest south of the mountain. | |||

?e ... '''nambo naiʔe''' she lives is the biggest in town = the house in which she lives is the biggest in town | |||

-lya ... the boat '''nailya''' she has just entered is unsound | |||

-lfe ... the lilly pad '''nailfe''' the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond. | |||

.. | |||

Now '''nài''' usually follows a noun. A relative clause can any noun ... or almost any noun. There are 2 nouns that can not take a relative clause. They are ... '''nèn''' and '''mìn'''. | |||

'''*nèn nài''' => '''ʃì nài''' | |||

'''*mìn nài''' => '''ò nài''' ... or '''nù nài''' | |||

In English we have what is called a headless relative clause. '''béu''' does not have this. The nearest '''béu''' has to a headless relative clause would be '''ʃì nài''' .... | |||

For example "what you see is what you get" would be rendered '''ʃì nài bwír sòr ʃì nài mìr''' | |||

.. | |||

'''kyù nài''' and '''dà nài''' introduced full relative clauses. These relative clauses are quite rare though. Much more common is ... | |||

However '''kyù''' and '''dà''' by themselves can intoduced deranked clauses. | |||

These deranked clauses have the same form as GO CC. Except that '''kyù''' or '''dà''' take the place of '''gò''' | |||

.. | |||

.. | |||

'''nài''' by itself is used to qualify a situation rather than a noun. | |||

For example "John hit a woman, which is bad" would be rendered '''jonos timpori glá_nài r kéu''' | |||

Note that there is a pause between '''jene''' and '''nài'''. If there was not this gap, the sentence would mean "John hit the woman who is bad" | |||

.. | |||

.. | |||

??? what about relativizing '''kài''' and '''làu''' ... '''làu bòi kài jono wò solbe''' => "as good as John as to drinking" | |||

??? what about non-restrictive relative clauses. | |||

.. | |||

.. | |||

I shot '''waulo è waulo yana fyakasori pà pulison''' = the man whose dog I shot reported me to the police. | |||

I shot '''waulo è yana fyakasori pà polison''' = the man whose dog I shot reported me to the police. | |||

.. | |||

=== ... Complement Clauses=== | |||

.. | |||

Certain verbs take a clause as one of their arguments. | |||

==== .. The GO complement clause ==== | |||

This clause always starts with the particle GO. Then the S or A noun. This is unmarked. Then the O noun. This is unmarked. Then other elements. Last of all is the verb. It ends in an -S (the final vowel marks the S or A ... is always A ... follows the infinitive ?? ) | |||

These clauses can stand alone and then they represent the optative mood. | |||

They are also equivalent of the English purposive clause. That is any clause that can be started off with "in order to". Note ... in English ... "in order to" is often shortened to "to". | |||

.. | |||

==== .. The BARE complement clause ==== | |||

.. | |||

These are aways started with the verb in its maSdar form. Followed by an unmarked S or A ('''yó''' or '''yú''' can be put in front of the S or A arguments). Then the unmarked object. Then other periphery arguments. | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The Verb Matrix for complement clauses === | |||

.. | |||

THINKING/LIKING ... all these verbs take a BARE CC if the subject of the CC is the same as the subject of the MC. For example ... | |||

'''wár timpa jene''' = I want to hit Jane | |||

If the subjects are different, then a GO CC must be used. For example ... | |||

'''wár gò jono jene timpas''' = "I want that John will hit Jane" or "I want John to hit Jane" | |||

Examples of verbs in this category incluse ...want, enjoy/like, fear, remember (fondly) | |||

MANIPULATUION | |||

Examples of verbs in this category incluse ... threaten/warm, invite etc etc. | |||

== ... Totality ... collectively or individually== | == ... Totality ... collectively or individually== | ||

Revision as of 23:15, 7 July 2016

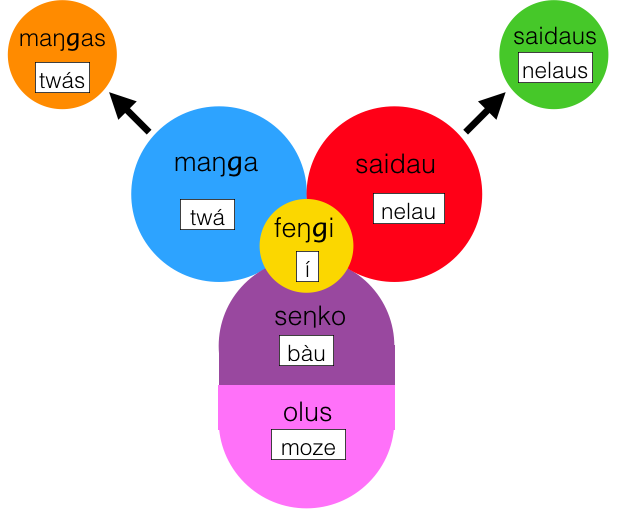

..... The 7 types of word

..

All words belong to one of the following 7 categories ...

..

1) feŋgi = particle ... this is a sort of "hold-all" category for all words (and affixes) that don't neatly fit into the other categories. Interjections, numbers, pronouns, conjunctions, determiners and certain words that would be classed as adverbs in English, are all classed as feŋgi.

An example is Í .. the preposition indicating the dative.

..

..

2) seŋko = object

An example is bàu ... "a man"

..

3) olus = material, stuff

An example is moze ... "water"

..

4) saidau = adjective

An example is nelau ... "dark blue"

..

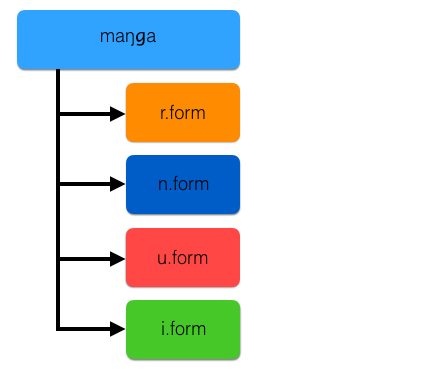

5) maŋga ... It is the basic form of the verb. Not considered or a noun or a verb (however the verbs built up from it by adding suffixes ARE considered full verbs.

An example is twá ... "to meet" or "meeting" (That is the concept of "meet" disassociated from arguments, tense, aspect or whatever).

..

6) maŋgas = Not considered or a noun or a verb (although more of a noun than a maŋga). Derived from a maŋga by suffixing -s. The maŋgas means one instance of the activity denoted by the maŋga. For example ...

twás = "a\the meeting"

..

7) saidaus = a noun derived from an adjective. A saidaus is derived from a saidau just by suffixing an -s. The saidaus means one object possessing the property denoted by the saidau.

An example is nelaus = a/the dark blue one ....... nò nelaus = a/the dark blue ones

..

..

The maŋgas and saidaus are transparently derived from the maŋga and saidau so there is no need to list them ... in a dictionary say. However they are important in the grammar of béu, particularly the maŋgas.

..

..... Saidaus

..

saidaus => noun OR noun phrase derived from a adjective.

saidaus baga => noun

saidaus kaza => noun phrase

saidaus kaza can have 8 possible elements.

These elements are exactly the same as the ones detailed in the seŋko section below, except the third element is saidaus baga instead of seŋko baga.

Actually saidaus can be derived from "locatives" and "genitives" as well as from saidau. For example ...

pobomaus = the one on top of the mountain

yós jene = the one belonging to Jane

..

..... Maŋgas

..

Note .... In English there are various means to derive a pure noun from a verb. For example ... "discover" + "y" => discovery ... "destroy" + "?tion" => destruction ... "run" + ∅ => a/the run

In béu there are no method for constructing pure nouns from verbs. However the maŋgas is close enough to a pure noun for MOST intents and purposes. Also it is 100% productive ... that is EVERY verb in béu has a maŋgas.

English is very untidy when it comes to verbal nouns. Consider ...

1) The killing of the president was an atrocious crime.

2) Killing the president was an atrocious crime.

You can see that one form "killing" is used in 2 different constructions. By the way ... "killing" in (1) is considered more noun-like.

..

maŋgas => verbal noun OR verbal noun phrase

maŋgas baga => verbal noun

maŋgas kaza =>verbal noun phrase

The order for building up maŋgas kaza is ...

1) ... a numerative

2) ... the maŋgas (mandatory)

3) ... a determiner (dí dè lò or nái) ... but actually these are quite uncommon elements in maŋgas kaza.

4) ... the A argument (if it exists) marked for the ergative.

5) ... the S or O argument next in its unmarked form (of course if you have an S arguments ... there was no A argument in step 2)

6) ... other clausal elements (for example time, adverb*, instrument, reason, purpose ) can be added now.

[ actually an emphatic particle can be put at the front of all this lot and a relative clause put at the end ... but these usages are so uncommon, that I decided not to list them ]

*If an adverb ending in -we finds itself up against the maŋgas, the -we affix will be dropped.

..

One pilana can be appended to maŋgas, and that is -pi.

The usuage is actually exactly the same as the English ... "while verbing"

..

..... Maŋga

..

This corresponds to what is called "infinitive" or "masDar" in other languages.

But in certain circumstances maŋga can be thought of as a noun. (Actually maŋgas has a better claim to nounhood ... after all it is discrete).

For instance they can be the S O or A argument in a clause. I guess that is their biggest claim to nounhood.

Another place they appear is as complements* of active verbs (live verbs). Two examples of this usage are given below ...

1) ... blèu = to hold ..... laila = to sing, singing ..... jenes blor laila bòi = Jane can sing well.

2) ... cùa = to depart ... timpa = to hit, hitting ... jonos cori timpa jene = John stopped hitting Jane

* Since all live transitive verbs in béu are capable of taking a noun complement (object), this usuage can not be said to make them appear any less noun-like, however restrictions/differences in the elements comprising maŋga baga compaired to seŋko baga plus there inability to take all the 17 pilana do make them appear less noun-like .... Actually I prefer not to talk about nouns, verbs and what have you but to stick to the 7 word types** which I have devised for béu. However out of pity for the reader (yes ... you) I quite often revisit the terminology of the Western Linguistic Tradition.

** Namely ... feŋgi seŋko olus saidau maŋga maŋgas and saidaus

..

maŋga => infinitive OR infinitive phrase

maŋga baga => infinitive

maŋga kaza => infinitive phrase

The order for building up maŋgas kaza is ...

1) ... the maŋga always comes first

2) ... the A* argument (if it exists) will immediately follow marked for the ergative.

3) ... the S* or O* argument next in its unmarked form (of course if you have an S arguments ... there was no A argument in step 2)

4) ... other clausal elements (for example dative object, time, adverb**, instrument, reason, purpose) can be added now.

*When talking about these arguments we are thinking as if the maŋga has been brought to life. And we have a verb in its r-form, n-form, i-form or u-form. Then the A O and S arguments would live up to their name. However the A O and S arguments we are talking about here are merely elements in a noun phrase (or infinitive phrase if you will), as opposed to arguments in a clause.

**If an adverb ending in -we finds itself up against the maŋga, the -we affix will be dropped.

..

Two pilana can be appended to maŋga ... these are -tu and -la

The -tu usuage is actually exactly the same as the English ... "by verbing"

The -la usuage produced an adjecting meaning " verbing at the moment of speach". As with all adjectives it can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu doikala = a/the walking man

bàu r doikala = a/the man is walking

Note ... bàu r doikala = bàu doikora ... exactly the same.

..

..... Saidau

..

The saidau has two uses in the béu. It can either be part of a NP or it can be a copular complement. For example ...

bàu gèu = a/the green man

bàu r gèu = a/the man is green

..

..... Olus

..

The olus kaza has the same stucture as seŋko kaza (see the next section) except for the second element

The second element is replaced with three elements ... call them elements (9), (10) and (11)

(9) is a numerative, (10) is called "holder" and (11) is the particle yó

we have come across yó before. it indicates possession, in this case no actual possession but a sort of "extention" of possession. For example ...

ifa hoŋko yó ʔazwo pona = two cups of hot milk

where element (9) is ifa "two", element (10) is hoŋko "cup" and element (11) is yó

Note ... just as yó is often dropped from seŋko kaza, (11) is often dropped if olus kaza is short. For example ...

ifa hoŋko ʔazwo = two cups of milk

Nouns denoting quality are olus through derived originally from saidau. For example ...

nelaumi = blueness (from nelau "dark blue") and geumai = greenness (from gèu "green")

..

..... Seŋko

..

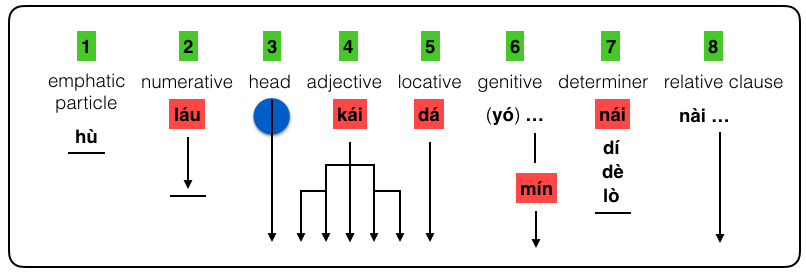

seŋko => noun OR noun phrase

seŋko baga => noun

seŋko kaza => noun phrase

seŋko can have upto 8 elements.

Below is shown the order in which they must occur.

..

..

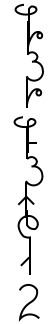

Elements 1, 2, and 7 have restricted membership, if fact element 1 has only one possibility, the word hù. The words with red background convert the noun phrase (or indeed the sentence in which the NP is embedded) into a question. A blue circle indicates the only mandatory element. Branching arrows indicate multiple possibilities.

... The head

3) ... the head \ seŋko baga

... The adjective

4) ... the adjective

More than one adjective is allowed. For example ... bàu gèu tiji = the little green man

kái "what type" can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu kái = what kind of green man ? ... noun phrase question

bàu gèu kái glà timpori = what kind of green man hit the woman ? ... sentence question

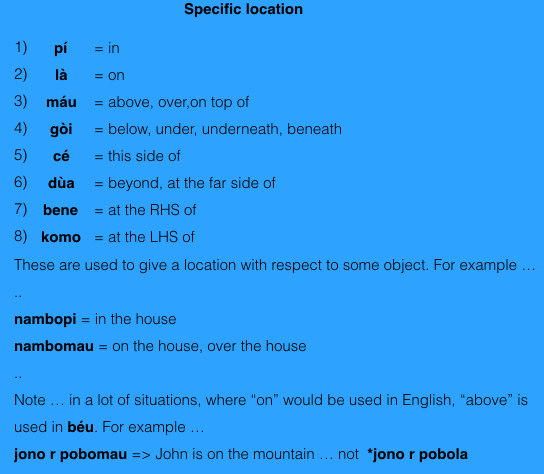

... The locative

5) ... the locative. For example ... bàu gèu tiji pobomau = the little green man on top of the mountain

A locative comprises of a noun plus a locative pilana ... also the pilana meaning "from" ... so in total "noun" + pi la mau goi ce dua bene komo ?e fi

dá "where" can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu dá = where is the green man ?

... The genitive

6) ... the genitive. For example jwado gèu nambomau yó jene = Jane's big green bird on top of the house

Note that the particle yó is usually dropped when the possessor is next to the head. However as other elements intervene, the likelihood that yó is used increases.

If mín (who) is used instead of jene in the above ... then we would have a question ...

jwado gèu nambomau yó mín = Whose big green bird on top of the house ? = Whose's the big green bird on top of the house ?

... The determiner

7) ... the determiner

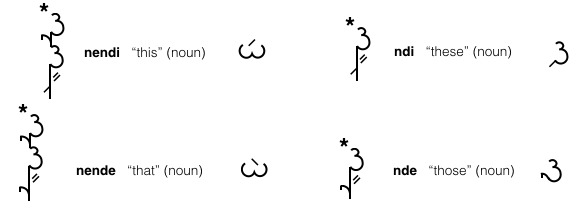

There are two determiners ... dí (this) and dè (that). For example ...

bàu gèu tiji pobomau dé = that little green man on top of the mountain.

The primary meaning is for comparing two objects that can be seen. Perhaps accompanied by gestures, dé will be appended to the further of the two objects and by way of distinction, dí will be appended to the nearer one.

nái (which) can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole noun phrase (or sentence) into a question. For example ...

bàu gèu tiji nái = which little green man ? ... noun phrase question

bàu gèu tiji nái glà timpori = which little green man hit the woman ? ... sentence question

Also lò "other" appear in this slot ... bàu gèu tiji lò = "the other little green man" or "another little green man"

Note ... dían => here, dèn => there ... not *dà dí and *dà dè

Note ... dí dè never appear independently as they do in English and many other languages. For example "this is good" => nèn dí r bòi .... literally "this THING is good"

Actually the above expression usually amalgamate to one word ... nendi r bòi "this is good" ... nende r bòi "that is good"

Note ... nò nendi is further contracted to => ndi and nò nende => nde .... these are syllabic nasals ... the only occurance of this sound in béu

Note that there is a short hand way to write these four words (shown on the RHS of the above diagram). Actually the long hand versions (shown on the LHS of the above diagram) are never used.

... The numerative

2) ... the numerative

Any number can go in here ... also jù "no" and nò "plurality particle".

láu (how many) can appear in this slot. In which case it turns the whole sentence into a question. For example ...

láu bàu r pobomau = How many men are on top of the mountain ?

With more complex seŋko baga it is usual to break it up in order to specify exactly which element is being questioned. For example ...

láu bàu gèu tiji pobomau nài doikura = " How many little green men on the mountain that are walking? " ... would be re-phrased as ...

wò bàu gèu tiji pobomau _ láu doikura = w.r.t. the little green man on top of the mountain, how many are walking ? ... or ...

wò bàu tiji pobomau nài doikura _ láu r gèu = w.r.t. the little man on top of the mountain who are walking, how many are green ?

... The relative clause

8) ... the relative clause

Relative clauses "RC" work pretty much the same as English relative clauses. The relativizer is nài (that, who). Here are some examples ...

yiŋkai nài doikore = the girl that has walked

bàu nài glás timpore = the man whom the woman has hit

glá nàis bàu timpore = the woman who has hit the man

bàu nàin glás fyori yiŋkaiwo = the man to whom the woman told about the girl

glá naiji bàus bundore nambo = the woman for whom the man has built a house

All the pilana can be appended to the relativizer to specify what roll the noun would have in the relative clause if it was a simple clause.

... The emphatic particle

1) ... the emphatic particle is hù.

hù is used where we would use what is called "right dislocation" in English. For example ...

bàus hù glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.

bàus hù glán nori alha @ = Is it the woman to whom the man gave flowers ?

hù might be used in exasperated when somebody can not see something. For example ...

| hù nendi | "this one !" | hù nende | "that one !" |

| hù nodi | "these ones!" | hù node | "those ones !" |

This can also used as a sort of vocative case ... not obligatory but can be used before a persons name when trying to get their attention. For example ...

hù jene = Hey, Jane

hù gì = Hey, you

..

..... Feŋgi

..

The feŋgi or particles are too diverse to say anything meaningful about them here. We will learn them one by one as we go though the ten chapters.

..

But just to fill out this section a bit, I will give you two sets of pronouns. One set being the pronouns in their unmarked form* and the other ... the pronouns in their ergative form**.

Here, for a transitive clause, "that which initiates the action" is called the A argument, and "that which is affected by the action" the O argument. Also, for an intransitive verb, the noun is called the S argument. It is convenient to make a distinction between all three cases. I follow RMW Dixon in using this terminology.

In most languages the S argument is marked the same way as the A argument. However in some languages the S argument is marked the same way as the O argument. These are called ergative languages. béu is one of these ergative languages. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative.

Below are the béu pronouns for the S and O arguments. This form can be considered the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | wìa | inclusive |

| us | yùa | exclusive | ||

| you | gì | you | jè | |

| him, her | ò | them | nù | |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

NOTE ... Pronouns differ from nouns in that their tones change between the ergative and the unmarked form. For a normal noun it is sufficient that -s is suffixed. For example ...

..

| bàu-s | glá | timp-o-r-e |

|---|---|---|

| align=center|woman | hit-3SG-IND-PRF |

==> The man hit the woman

| bàu | glá-s | timp-o-r-e |

|---|---|---|

| man | woman-ERG | hit-3SG-IND-PRF |

==> The woman hit the man

..

Below are the pronouns in the ergative form.

..

| I | pás | we | wías |

| we | yúas | ||

| you | gís | you | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

jè and jés are the second person plural forms.

There is one other pronoun ... the reflexive pronoun tí. This is always an O argument. Notice that it is the only O argument with a high tone.

* In the Western Linguistic Tradition, these "forms" are called "cases". The English word case used in this sense comes from the Latin casus, which is derived from the verb cadere, "to fall", from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱad-. The Latin word is a calque of the Greek πτῶσις, ptosis, "falling, fall". The sense is that all other cases are considered to have "fallen" away from the nominative (considered the unmarked form in Latin).

** By the way, there are 17 marked forms in béu ... the ergative being just one of these 17.

..

..... Live verbs

helga = life, helga = alive .... what abiut angwa ??? helkas a clause ??

Lets take the solbe to explain these different forms. solbe is a maŋga and it would be found in the dictionary ... and if it was an English/ béu dictionary ... the translation "to drink" would lie alongside it.

An example of one of its (many) r.forms is solbori = He/she/it drank ....... so the r.form corresponds to a verb in indicative mood.

An example of one of its (handful of) s.forms is gò solban = I wish I could drink ....... corresponds to a sort of subjunctive mood.

The u.form (only one u.form per word) is solbu = drink ! ....................... so the u.form corresponds to a verb in imperative mood.

The i.form (only one i.form per word) is solbi ... this is the fornm used in verb chains and will be explained later.

We will go into a lot more detail about all these forms in the next chapter.

..

..

... Word order

..

In English it is the order of the verb and the arguments that shows who is the doer and what is the "done to". Namely the A and S argument come before the verb and the O argument after.

[ English is a non-ergative language and hence the A and S argument get treated in the same way. ]

In béu, to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", the suffix -s is appended to the A argument. For example ...

glás bàu timpore => The woman has hit the man ..... (with "the man" being the O argument)

glá bàus timpore => The man has hit the woman ...... (with "the man" being the A argument)

bàu doikora => The man is walking ........................... (with "the man" being the S argument)

[ béu is an ergative language and hence the O and S argument have the same form. ]

But even though béu doesn't use word order to show who is the doer and what is the "done to", it does use word order for another purpose. Namely to show if an argument is definite* or not. For example ...

bàu doikor = The man walks

doikor bàu = A man walks

So we see ... an argument coming before the verb is definite and one coming after the verb is indefinite.

In English only 2 orders are found. Namely ... SV and AVO ... (V = verb). However in béu you have what is called "free word order". This means that you can come across the following eight orders ... SV, VS, AVO, AOV, VAO, OVA, OAV and VOA.

But actually in a piece of discourse, it is most likely that the S or A argument are old information and probably the topic (the thing that you have been going on about for some time). In béu an established topic is usually dropped and so the eight sentence orders shown above collapse to 3. Namely ... V(s)** , O V(a) and V(a) O

* And when I say definite, I mean that the person being spoken to can identify X as one particular X instead of some X or any X ... if X was a person, then the person being spoken to could put a face to X.

** V(s) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the S argument and V(a) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the A argument.

..

... The Case system

..

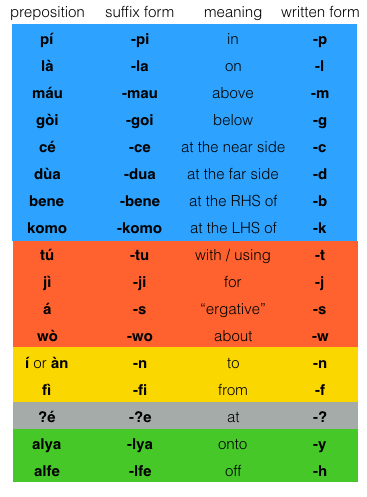

We have just mentioned the ergative form. In total there are 17 cases of course (if you were to include the unmarked case as well you have 18 different forms). They are called the pilana.

These are attached to a noun and show the relationship of that noun with respect to the rest of the sentence.

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila (v) = to place, to position

pilana (a, n) = positioning, the positioner

..

..

The pilana are either realized as affixes or as prepositions.

Whether the pilana appears as an suffix or a preposition depends on seŋko * ... if seŋko baga, then the affix is used ... if seŋko kaza, then the preposition is used. For example ...

nambodua = beyond the house

dùa nambo yó yinkai hauʔe = beyond the house of the pretty girl

* or in other words, if the NP is only one word one uses the suffix, and if the NP is more than one word one uses the preposition }

..

Note on the script ... If they are realized as affixes then, in the béu script uses a sort of shorthand. That is the affix is represented as one letter.

.. As parts of speech

..

pilana of location phrases (i.e. nouns with 1 -> 8 or 15) can be considered adjectives if they come after a noun and adverbs if they come after a verb. They must come after a noun or a verb. Sometimes they come after the copula*. In this case they are adjectives. Now often the copula is dropped ... but if this dropping results in any ambiguity it can be readily "undropped".

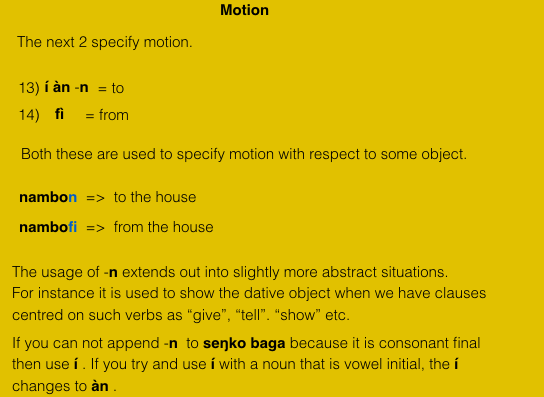

pilana of motional phrases (i.e. nouns with 13, 14, 16 or 17) can be considered adverbs. They can come in any position because it is understood that they are qualifying the verb.

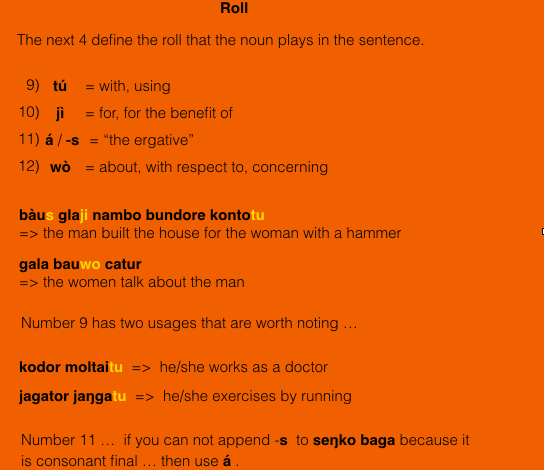

pilana phrases defining sentence rolls (i.e. nouns with 9, 10, 11 or 12) can come anywhere. They are considered nouns.

* [ Notice that in English, you can either say ... "a bird is in the tree" or "in the tree is a bird"

In béu only jwado r ʔupaiʔe is valid ... also note that in this case jwado is not definite because it is left of the verb. That rule doesn't work with the copula. ]

..

... Questions

..

... The 9 Question Words

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 8 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "whose", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

Note ... there was alsp a "whom" until quite recently.

These are the most profound words in the English language.

However these question words have over the mellenia been sequestered to support other functions. For example "who" can be used to ....

1) Solicit a response in the form of a persons identity

2) As a relativizer particle ... for example ... "The man who kicked the dog"

3) As a complement clause particle ... for example ... "She asked who had kicked the dog"

4) In the compound "whoever" which is an indefinite pronoun.

Only in the first example is "who" asking a question.

..

béu has 10 question words ...

..

| dá | where |

| kyú | when |

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| sái | "why" |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| láu | "how much" or "how many" |

| nái | which |

| ʔala | which |

| ʔai? | "solicits a yes/no response" |

..

If you hear any of these words you know you are being solicited for some information. That is these words have no other function apart from asking questions.

..

nós and mís are the ergative equivalents to nén and mín (the unmarked words)

English is among the 1/3 of world languages which fronts a question word. I guess béu would be considered a content-question-word-fronter as well.

dá kyú nén nós mín and mís are always sentence initial. (but pilana are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.)

kái láu and nái are usually found in a NP. These NP's are always made sentence initial. ( kái and nái appearing after the head, láu before. )

Here are some examples of these words in action ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 ... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 ... í mín bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 ... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... í glá nái bàus nori alha = the man gave the flowers to which woman ?

Question 5 ... á bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 6 ... alha kái bàus glán nori = what type of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 7 ... láu alha bàus glán nori = how many flowers did the man give the woman

Question 8 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔala cokolate = Did the man gave the woman flowers or chocolate ?

Question 9 ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man gave the woman flowers ?

..

"why" is expressed as nenji which means "what for" (by the normal pilana rules, it should be jì nén. However jì nén is never seen ... always nenji)

"how" is expressed as wé nái which means "which way" or "which manner"

..

... Polar Questions and the focus particle

..

A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

To turn a normal statement into a polar question the particle ʔai? is stuck on at the very end.

It has its own symbol (and I transcribe it as ʔai?) because it possesses its own tone contour.

I have mentioned this particle in chapter 1 (if you look back you can see its exact tone contour). Here is its symbol again ...

And here is an example of it in action ...

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

..

ʔai? is neutral as to the response expected ... well at least in positive questions.

To answer a positive question you answer ʔaiwa "yes" or aiya "no" (of course if "yes" or "no" are not adequate, you can digress ... the same as any language).

Here is an example of a positive question ...

glá r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman beautiful ?

If she is beautiful you answer ʔaiwa, if not you answer aiya*.

..

To answer a negative question it is not so simple. ʔaiwa and aiya are deemed insufficient to answer a negative question on their own. For example ...

glá bù r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman not beautiful ?

If she is not beautiful, you should answer bù hauʔe**, if she is you can answer either hù hauʔe or glá r hauʔe

I guess a negative question expects a negative answer, so a positive answer must be quite accoustically prominent (that is a short answer ("yes" or "no") is not enough)

..

You will have noticed hù in the above example. This is the focus particle. It has a number of uses. When you want to emphasis one word in a clause, you would stick hù in front of it***.

Another use for hù is when hailing somebody .... hù jono = Hey Johnny

You can also stick it in front of someone's name when you are talking to them. However it is not a "vocative case" exactly. Well for one thing it is never mandatory. When used the speaker is gently chiding the listener : he is saying, something like ... the view you have is unique/unreasonable or the act you have done is unique/unreasonable. When I say unique I mean "only the listener" hold these views : the listener's views/actions are a bit strange.

When stuck in front of a non-multi-syllable verb you get an imperative. For example ... hù nyáu = Go home

hù can also be used to highlight one element is a statement or polar question. For example ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement ... bàus hù glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.****

Unfocused question ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man give flowers to the woman ?

Focused statement ... bàus hù glán nori alha ʔai? = It is to the woman that the man gave flowers ?

..

Any argument can be focused in this way.

..

*These words have a unique tone contour as well ... at least when spoken in isolation. I suppose I should have given these two words a symbol each ... if I wanted to be consistent.

**Mmm ... maybe you could answer ʔaiwa here ... but a bit unusual ... not entirely felicitous.

***In English, when you want to emphasis a word, you make it more accoustically prominent : you don't rush over it but give it a very careful articulation. This is iconic and I guess all languages do the same. It is a pity that .....there is no easy way to represent this in the English orthography apart from increasing the font size or adding exclamation marks.

****English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to an element in a clause.

..

... The Generic noun equivalents

..

..

| dà | place |

| kyù | occasion |

| nèn nòs | thing |

| mìn mìs | person |

| kài | kind, type, sort |

..

| làu | amount |

..

... The Relativizer

..

In English, one of the functions of "who" is as a relativizer ... a particle that introduced a relative clause. For example ....

"The man who ate the chicken got sick"

Also in English, one of the functions of "that" is as a relativizer. For example ....

"The chicken that was eaten must have been off"

..

In béu there is only one relativizer ... nài. For example ...

glà nài bàus timpori_sòr hauʔe = The woman that the man hit, is beautiful.

..

nài takes case affixes the same way that a normal noun would. For example ...

pi ... the basket naipi the cat shat was cleaned by John.

la ... the chair naila you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

mau

goi

ce

dua

bene

komo

tu ... báu naitu ò is going to market is her husband = the man with which she is going to town is her husband ... kli.o naitu he severed the branch is rusty

ji ... The old woman naiji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

-s ... báu nàis timpori glá_sòr ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

wo ... The boy naiwo they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

-n ... the woman nàin I told the secret, took it to her grave.

fi ... the town naifi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

?e ... nambo naiʔe she lives is the biggest in town = the house in which she lives is the biggest in town

-lya ... the boat nailya she has just entered is unsound

-lfe ... the lilly pad nailfe the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.

..

Now nài usually follows a noun. A relative clause can any noun ... or almost any noun. There are 2 nouns that can not take a relative clause. They are ... nèn and mìn.

*nèn nài => ʃì nài

*mìn nài => ò nài ... or nù nài

In English we have what is called a headless relative clause. béu does not have this. The nearest béu has to a headless relative clause would be ʃì nài ....

For example "what you see is what you get" would be rendered ʃì nài bwír sòr ʃì nài mìr

..

kyù nài and dà nài introduced full relative clauses. These relative clauses are quite rare though. Much more common is ...

However kyù and dà by themselves can intoduced deranked clauses.

These deranked clauses have the same form as GO CC. Except that kyù or dà take the place of gò

.. ..

nài by itself is used to qualify a situation rather than a noun.

For example "John hit a woman, which is bad" would be rendered jonos timpori glá_nài r kéu

Note that there is a pause between jene and nài. If there was not this gap, the sentence would mean "John hit the woman who is bad"

.. ..

??? what about relativizing kài and làu ... làu bòi kài jono wò solbe => "as good as John as to drinking"

??? what about non-restrictive relative clauses.

.. ..

I shot waulo è waulo yana fyakasori pà pulison = the man whose dog I shot reported me to the police.

I shot waulo è yana fyakasori pà polison = the man whose dog I shot reported me to the police.

..

... Complement Clauses

..

Certain verbs take a clause as one of their arguments.

.. The GO complement clause

This clause always starts with the particle GO. Then the S or A noun. This is unmarked. Then the O noun. This is unmarked. Then other elements. Last of all is the verb. It ends in an -S (the final vowel marks the S or A ... is always A ... follows the infinitive ?? )

These clauses can stand alone and then they represent the optative mood.

They are also equivalent of the English purposive clause. That is any clause that can be started off with "in order to". Note ... in English ... "in order to" is often shortened to "to".

..

.. The BARE complement clause

..

These are aways started with the verb in its maSdar form. Followed by an unmarked S or A (yó or yú can be put in front of the S or A arguments). Then the unmarked object. Then other periphery arguments.

..

... The Verb Matrix for complement clauses

..

THINKING/LIKING ... all these verbs take a BARE CC if the subject of the CC is the same as the subject of the MC. For example ...

wár timpa jene = I want to hit Jane

If the subjects are different, then a GO CC must be used. For example ...

wár gò jono jene timpas = "I want that John will hit Jane" or "I want John to hit Jane"

Examples of verbs in this category incluse ...want, enjoy/like, fear, remember (fondly)

MANIPULATUION

Examples of verbs in this category incluse ... threaten/warm, invite etc etc.

... Totality ... collectively or individually

..

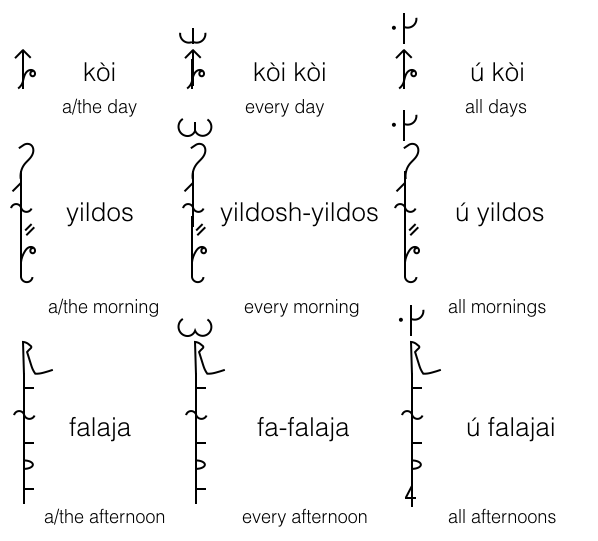

Sometimes we want to talk about all members of the category "noun" acting (or being acted upon) COLLECTIVELY.

For this we use the particle ú before the plural of the noun. For example ...

moltai = a/the doctor

moltai.a = doctors

ú moltai = all doctors

Note ... the same word, when appended to a noun, means "the whole" or "entire". For example ...

falaja ú = all morning

..

The opposite of the above, is when all members of the category "noun" is acting (or is being acted upon) INDIVIDUALLY.

By doubling the noun (or the first part of a noun) you give what can be called a distributive meaning.

Some examples ...

kòi = day

kòi kòi = every day

moltai = doctor

moltai moltai = each doctor

falaja = afternoon

fa falaja = every afternoon

Notice that for words over two syllables, only the first syllable is prefixed.

..

The "word-hood" of these duplications is murky. I am writing them here as two separate words ... i.e. fa falaja. But maybe fafalaja or fa-falaja would be more appropriate.

Single syllable words retain there tone when duplicated ... which indicates two separate words. However you also get phonological processes that are usually only word internal. That is to say, these structures show "sandhi".

For example ...

yildos yildos (every morning) would be pronounced / jildoʃ jildos /

bàu bàu (every man) could be pronounced / bàu vàu /

Anyway ... these constructions are never written out in full. Instead a special symbol is placed above the simple noun. This symbol can vary a bit, depending on the font being used : it can vary from a lower half circle bisected by a vertical stroke to a shape that looks a bit like the Arabic shaddah.

For example ...

It some contexts, semantically, it does not matter whether the individual or the collective form is used. When this is the case, the default choice is "individual" structure. ú tends to be used with tangible nouns more, it is hardly ever used with nouns denoting periods of time.

Note (as in English) the plural verb form is used for the collective structure, the singular verb form for the individual structure. For example ...

ú bàu súr = all men are

bàu bàu sór = every man is

TO THINK ABOUT ...

?à ?à bàu hù ?ís = any man that you want ( ?ís ... "you would want" ???? )

?ài ?ài bàu hù ?ís = any men that you want

?ài bàu = some men

..

..... lé .... lú .... lò

..

Earlier we have seen that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilana affixed to them. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilana then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

jonos jenes solbur moze = "John and Jane drink water"

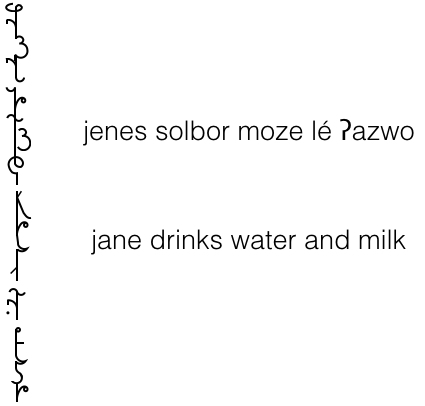

In the absence of an affixed pilana, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lé should be placed between them. For example ...

jenes solbori moʒi lé ʔazwo = "Jane drank water and milk"

jonos jenes bwuri hói sadu lé léu ʔusʔa = John and Jane saw two elephants and three giraffes.

[ Compare the above two examples to á jono jene solbori moze = Jane's John drank water ... i.e. The John that is in a relationship with Jane, drank water ]

This word is that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

..

Note ... in the béu script, the "o" before "r" is always dropped. This is just a sort of short hand thing.

..

The following construction is also found.

lé moze lé ʔazwo = "both water and milk"

The above construction emphasizes the "linking" word lé

Another linking word is lú meaning "or".

jenes blor solbe moze lú ʔazwo = "Jane can drink water or milk"

The following construction is also found.

lú moze lú ʔazwo = "either water or milk"

The above construction emphasizes the "linking" word lú

There is another word that corresponds to the English "or". This is ʔala and it is a question word. For example ...

ʔís moze ʔala ʔazwo = "would you want water or milk"

And the answer expected of would be either "water" or "milk"

Say you were asking somebody if they were thirsty and you had only water or milk to give them. Then you would say ... ʔís moze lú ʔazwo ʔai@

The expected answer to the above question would be either "yes" or "no" (as is always the case when you have @ ( @ is pronouced a bit like ʔai but has contour tone instead of a normal high tone, it has a special symbol and I am using "@" to represent this symbol in my transliteration)).

Now if the question was "would you want water or milk, or both" you should say ...

ʔís mose ʔala ʔazwo ʔala leume

But sometimes (either because of the laziness of the speaker or because the likelyhood was not considered) ... ʔís moze ʔala ʔazwo ʔala leume comes out as ʔís moʒi ʔala ʔazwo.

So ʔís leume (I would like both) is an acceptable answer to the question ʔís moze ʔala ʔazwo

If the questioner would like to rule out the answer ʔís leume he would use the construction .

ʔís ʔala moze ʔala ʔazwo

So ʔala before the first item does exactly the same as lé or lú before the first item : it emphasizes the linking word.

..

... "no"

..

In béu, jù corresponds to "no".

"neither water nor milk" would be translated as jù moʒi jù ʔazwo

..

... lists

..

So far we have restricted ourselves to two items. We can summarize the system for two items as below ...

..

| lé | giving | 2 | items | |||||

| lú | giving | 1 | item | ..... | ʔala | asking for | 1 | item |

| jù | giving | 0 | items |

..

However we can join up more than two items. When more than two items are joined by the above 4 linking words, it is considered good style to have the linking word before the first item and the last item, before each item (except the first and the last) should be a slight pause (I call it a gap ... see "punctuation and page layout" earlier on this page).

For example ...

jenes bwori lé ifa sadu _ uba ʔusʔa _ ega moŋgo lé oda gaifai falaja dí = Jane saw two elephants, three giraffes, four gibbons and five flamengos this morning.

..

... other

..

lò = other

lòi = others

kyulo = again

welo = otherwise

..

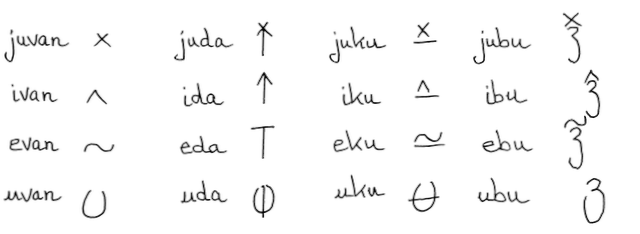

..... Correlatives

..

| juvan | nothing | juda | nowhere | juku | never | jubu | nobody |

| ivan | anything | ida | anywhere | iku | anytime | ibu | anybody |

| evan | something | eda | somewhere | eku | sometime | ebu | somebody |

| uvan | everything | uda | everywhere | uku | always | ubu | everybody |

These correlatives are always written in their shorthand form. See the chart above.

The first column is a contraction of jù fanyo, í fanyo, é fanyo and ù fanyo (fanyo = thing)

The second column is a contraction of jù dà, í dà, é dà and ù dà (dà = place)

The third column is a contraction of jù kyù, í kyù, é kyù and ù kyù (kyù = time/occasion)

The last column is a contraction of jù glabu, í glabu, é glabu and ù glabu (glabu = person)

The non-contracted forms are still used, usually when emphasis is wanted.

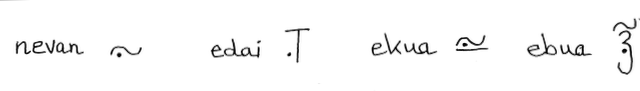

There is another row in the above table.

This is the plural equivalent of the third row of the table above. The emphatic form of the above series would be ...

è fanyo, è dá, è kyù and è glabu .... if these elements were under* the main verb, it would be more normal to use ...

fanyoi, nò dá, nò kyù and glabua .... and actually, if any word from the third row of the main table came under the main verb, you could just use ...

fanyo, dá, kyù and glabu ... in this position you have probably a 50% chance of coming across evan and a similar chance to come across fanyo ... the same with eda, eku and ebu.

One interesting point is ... well for example ubu can mean "each person" and "all the people". If ubu was the S or A argument there could be one of two verbs in a SVC. One would have the meaning "to do together"/"to cooperate" and the other would have the meaning "to work alone". If ubu was the O argument or has some other roll in the sentence there is a partical that can be put in above* ubu. This particle means something like "individual" or "independent" and would disambiguate the meaning of the béu sentence.

*I was going to say 'after" and "before", however as the béu writing system is vertical I thought I should get in the spirit of things and use "under" and "above".

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences