Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective: Difference between revisions

| Line 493: | Line 493: | ||

However the object slot can be filled with a [[Image:TW_540.png]] in which case '''día''' means "to start". For example ... '''jonos dori solbe''' = John started to drink | However the object slot can be filled with a [[Image:TW_540.png]] in which case '''día''' means "to start". For example ... '''jonos dori solbe''' = John started to drink | ||

. | [[Image:TW_527.png]] | ||

.. | '''liga''' is a transitive verb and the O argument is usually filled by a location. For example ... '''jonos ligor london''' = John stays in London | ||

.. | However the object slot can be filled with a [[Image:TW_540.png]] in which case '''liga''' means "to continue". For example ... '''jonos ligori solbe''' = John carried on drinking | ||

There is no verb '''liganau'''. | |||

[[Image:TW_528.png]] | |||

''' | '''dwài''' is a transitive verb and the O argument is usually filled by a location. For example ... '''waulois fanfa dwura''' = The wolves are chasing the horse | ||

However the object slot can be filled with a [[Image:TW_540.png]] in which case '''dwài''' means "try". For example ... '''jonos dwora nyáu nambo''' = John is trying to go home | |||

[[Image:TW_529.png]] | |||

[ | [[Image:TW_530.png]] | ||

[ | [[Image:TW_531.png]] | ||

[[Image:TW_532.png]] | |||

[[Image:TW_533.png]] | |||

.. | However when the subject of '''día''' and the '''maŋga''' subject are different then the verb '''gàu''' "to do" or "to make" must be used. For example ... | ||

'''jonos gori jene solbe''' = John made Jane drink | |||

'''jonos gori gò jene día solbes''' = John made/forced Jane to start to drink | |||

[ | [Note that is the above example, the '''maŋkas''' word order is set. That is '''jene día solbe''' is in a fixed order] | ||

[ | [Actually '''jonos gri jene día solbe''' is also expressible as '''jonos dainri jenen solbe'''. So we have two new verbs ... '''dianau''' and '''cuanau'''. Notice that Jane is in the dative case so these two new verbs are (V2)] | ||

The engine '''dri doika''' = The engine started | |||

Here '''doika''' "to walk" is a sort of dummy verb meaning to operate/run. It is necessary since '''día''' is a transitive verb. | |||

.. | |||

[[Image:TW_534.png]] | [[Image:TW_534.png]] | ||

Revision as of 07:35, 12 June 2016

.. Adjectives => Verbs

..

Some concepts that are coded as adjectives in English, are coded as verbs in béu. Usually they are body internal processes or states. So joining "to sleep", "to love", "to hate" (which are stative verbs in English) we have concepts like "to be angry", "to be jealous", "to be healthy" encoded as verbs in their base state.

[Note ... most of these are mental states]

Now in béu all multi-syllable adjectives become verbs simply by adding the verb train to them. For example ...

coga = wide

coguran komwe = it seems they have widened the road

However ... to make the corresponding maŋga you must add the suffix do. For example ...

cogado = to widen

For the few mono-syllabic adjectives that exist, this suffix must be present all the time. For example ...

àu = black

audo = to blacken

auduran komwe = it seems they have blackened the road

Notice that these derived verbs are all transitive. To have the intransitive sense, you must use the verb tezau "become" along with the adjective.

..

..... 4 adjectives => verbs via derivation

..

| bòi* | good |

| kéu* | bad |

| fái | rich ** |

| pàu | bland |

..

The above adjectives have an "s" affixed and change into verbs. However the meanings derived are a bit quirky.

..

| bòis*** | to be healthy/health | boizora | she is healthy |

| kéus | to be sick/illness | keuzora | he is ill |

| fáis | to be attentive/to like/attention | faizora | she is interested |

| pàus | to be bored/boredom | pauzora | he is bored |

..

* The adverb derived from these words are slightly irregular. Instead of boiwe it is bowe. People often shout this when impressed with some athletic feat or sentiment voiced ... bowe bowe (well done) => bravo bravo Also instead of keuwe we have kewe. People often shout kewe kewe kewe if they are unimpressed with some athletic feat or disagree with a sentiment expressed. Equivalent to "Booo Boo".

**"rich" in its non-monetary sense. If applied to food it means many flavours and/or textures. If applied to music it means there is polyphony. If applied to physical design it means baroque.

***This appears in its subjunctive form as an expression often used when people are parting for what is expected to be some time. boiʒis => "may you be well".

..

... 10 adjectives which never appear as verbs

..

| sài | young |

| gáu | old (of a living thing) |

| jini | clever, smart |

| tumu | stupid, thick |

| wenfo | new |

| yompe | old, former, previous |

| dìa | east, dawn, sunrise |

| cúa | west, dusk, sundown |

| bene | right, positive |

| komo | left, negative |

..

Of course you can always use a periphrastic expression if you wanted. For example ...

sàr tumu = I am stupid

tezar tumu = I become stupid

gàr tumu = I make (someone) stupid

Some of the above can be considered more nouns than verbs. For example ... dìa and cúa.

These two are of interest for another reason ... dìa combines with día .. "to arrive" to make the word ... diadia .. "to happen". Also cúa combines with cùa .. "to depart" to make the word ... cuacua .. "to fade away".

Note that although the components going into these words have exactly opposite meanings, the compound words do not.

diadia appears in quite common expressions. For example ...

nén r diadila = "what's happening"

nén diadori = "what happened"

..

... 16 adjectives => verbs with zero derivation

..

| boʒi | better | kegu | worse |

| faizai | richer | paugau | blander |

| maze | open | nago | closed |

| saco | fast | gade | slow |

| fazeu | empty | pagoi | full |

| hauʔe | beautiful | ʔaiho | ugly |

| ailia | neat | aulua | untidy |

| coga | wide | deza | narrow |

Note that the first two are irregular comparatives. The standard method for forming the comparative and superlative is ... ái = white : aige = whiter : aimo = whitest. ..

These adjectives directly become verbs. For example ...

| bozor | he improves | kegor | he worsens | boʒido | to improve | kegudo | to made worse |

| faizor | she develops | paugado | she runs down | faizado | to enrich/develope | paugado | to run down |

But notice that the infinitive form of this derived verb has the affix "do".

..

... 38 adjectives => verbs with derivation

..

| ái | white | àu | black |

| hái | high | ʔàu | low |

| guboi | deep | sikeu | shallow |

| seltia | bright | goljua | dim |

| taiti | tight | jauju | loose |

| jutu | big | tiji | small |

| felgi | hot | polzu | cold |

| baga | simple | kaza | complex |

| naike | sharp | maubo | blunt |

| nucoi | wet | mideu | dry |

| wobua | heavy | yekia | light |

| pujia | thin | fitua | thick |

| yubau | strong | wikai | weak |

| fuje | soft | pito | hard |

| gelbu | rough | solki | smooth |

| ʔoica | clear | heuda | hazy |

| selce | sparce | goldo | dense |

| cadai | fragrant | dacau | stinking |

| igwa | elegant | uʒya | crude |

These adjectives do not become verbs directly, even as finite verbs (helgo form) they have the affix do.

| aidor | he whitens | audor | he blackens | aido | to whiten | audo | to blacken |

| haidor | she raises/rises | ʔaudor | she lowers | haido | to raise | ʔaudo | to lower |

So why do some verbs have do in their finite form and others not. Well monosyllable adjectives always take do. As for the rest, the ones that appear often as verbs, drop the do in their finite form.

Notice that for multi syllable adjectives ending in a diphthong, the final vowel s dropped before appending do.

..

However not quite all antonyms fall into the above pattern. For example ...

loŋga = tall, tìa = short

wazbia = far, mùa = near ... wazbo = distance, wazbai = about 3,680 mtr (the unit of distance)

..

..... The primary verb

..

If then the

A V2 that can take a thing.kas dead.kas sa.kas or takas as the naked noun.

1) ʔár wèu => I want a car

2) ʔár jó nambon => I want to go home

3) ʔár jís nambon => I want you to go home

4) ʔár tà gís timpiru ò => I want YOU to hit her/him

2) Is a very common construction ... the same subject for "want" and the second verb. The second verb is dead.

3) Different subjects for the two verbs ... not so common ... second verb is half-dead.

4) As the complement to ʔár gets more complicated there is more a tendency to use the tà construction.

Note that in béu there is no verb equivalent to "wish". You would use the construction ...

hà jau.e timpis ò = "if only you would hit him" to express this sentiment.

............

So in the above ... the construction as in 1) is used when the person doing the wanting, is also the subject (A or O) of the action required and the second action sort of "follows on" from the "wanting".

The construction as in 2) and 3) is used when the person doing the wanting is different from the subject (A or O) of the action required. The second action again sort of "following on" from the "wanting".

The construction as in 4) is used when the person doing the wanting is different from the subject (A or O) of the action required AND the second action DOES NOT "following on" from the "wanting".

..

..... The same or different

..

Also gò "same"/"the same" and sé "other"/"different" appear in this slot.

Note ... for "the other", NP before the verb : for "another", NP after the verb)

1a) jono lé jene sùr gò bèn = "John and Jane are the same"

Note ... logically jono lé jene sùr gò ... means the same, but in a sentence of this type, it feels incomplete without the bèn ... euphony.

1b) jono r gò jene = "John is the same as Jane"

The above two examples are ambiguous as to whether John and Jane are the same w.r.t. one characteristic or the same w.r.t. all characteristic.

2a) jono lé jene sùr gò jutuwo = "John and Jane are the same size"

2b) jono r gò jene jutuwo = "John is the same as Jane, sizewise" = "John is the same size as Jane"

[Note jutuwo ... does this mean that jutumi is extinct ?? ]

All the above sentences can be negated EITHER by adding -ke to the copula OR by replacing gò with sé

gobis = similar .... sé related to lò "other" ??

..

OTHER ... A FURTHER OBJECT (SAME TYPE) IS BROUGHT INTO CONSIDERATION

DIFFERENT .... TWO OBJECTS DIFFER WRT ONE QUALITY

SAME ... TWO OBJECTS "ARE ONE AND THE SAME"

SAME ... TWO OBJECTS "DON'T DIFFER WRT ANY QUALITY

..

..... 13 key verbs

..

..

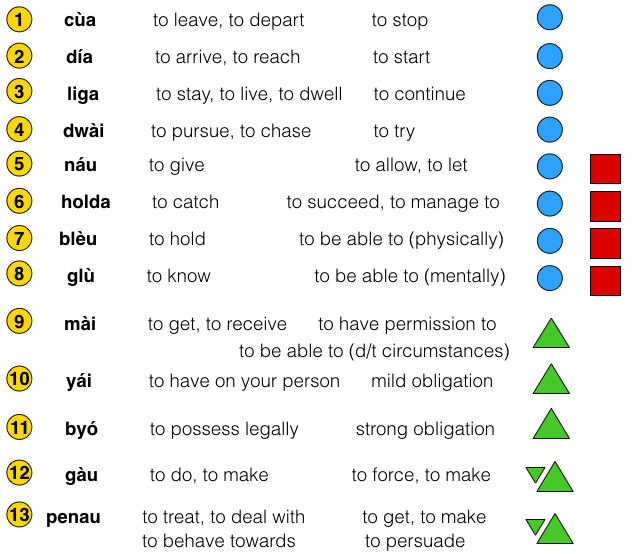

The above chart gives 13 important (and common) verbs. They can all take nouns as objects. However they can also take complement clauses (CC from now on) instead of objects. In béu there are four types of complement clause. Three of them are shown above.

![]() ...... represents a tà CC. This is more or less equivalent to a CC in English introduced by "that". This béu CC is introduced by the particle tà, and the CC itself is identicle to a normal clause.

...... represents a tà CC. This is more or less equivalent to a CC in English introduced by "that". This béu CC is introduced by the particle tà, and the CC itself is identicle to a normal clause.

![]() ...... represents a maŋga CC. There is no particle to introduce the clause and the verb ... as you would suspect, is in its maŋga form. The maŋga always starts a maŋga phrase (MP from now on). This is immediately followed by by the subject ... with -s appended if an A argument.

...... represents a maŋga CC. There is no particle to introduce the clause and the verb ... as you would suspect, is in its maŋga form. The maŋga always starts a maŋga phrase (MP from now on). This is immediately followed by by the subject ... with -s appended if an A argument.

Note ... The structure of a maŋgas phrase (MsP from now on) is the same as a MP. However this is a 100% noun, and a MsP can wrap itself in all the things that a seŋko can.

Also Note ... Because the verb comes first in a MP and MsP ... the distinction between definite and indefinite can not be maintained.

![]() ... represents a gò CC. English has no equivalent to this CC. The introductory particle is gò but this is often dropped. The verb form is the same as maŋga but with -n appended.

... represents a gò CC. English has no equivalent to this CC. The introductory particle is gò but this is often dropped. The verb form is the same as maŋga but with -n appended.

This CC requires a bit of an explanation. It always follows a verb* such as mài, yái, byó, gàu and penau. When the subject is the same as the main clause it is ... as you would expect, dropped. When a gò CC has no subject, it is permissible to drop gò. In fact is would be usual ... the only reason to retain it would be emphasis or euphony. When a subject is necessary in a gò CC, I use the symbol ![]()

As can be seen from the chart mài, yái and byó never take a subject-containing gò CC ... whereas gàu and penau always take a subject-containing gò CC.

gò jù = lest ???

*Actually not really true. Sometimes it occurs sentence initial. In this position the clause has an "optative meaning. It expresses wishful thinking. For example ... gò (pás) blàr doika = "if only I could walk"

Also used for curses and benedictions (by frequency of usage the former outnumber the latter by about 10 to 1 ). For example ... gò diablos ʔawon ò = "May the Devil take him"

An optative utterance is not a command, also it is not giving information. It does reveal the speakers emotion though. And presumably the speaker feels better for venting these emotions. Maybe we should call this the "ventative" instead of the "optative" ;-)

As well as the spontaneous optative clause ... there are also some set optative expressions that are expressed in certain formal situations or rituals. For example xxx = "God save the king"

cùa is a transitive verb and the O argument is usually filled by a location. For example ... jonos cori london = John left London

However the object slot can be filled with a ![]() in which case cùa means "to stop". For example ... jonos cori solbe = John stopped drinking

in which case cùa means "to stop". For example ... jonos cori solbe = John stopped drinking

día is a transitive verb and the O argument is usually filled by a location. For example ... jonos dori london = John arrived in London

However the object slot can be filled with a ![]() in which case día means "to start". For example ... jonos dori solbe = John started to drink

in which case día means "to start". For example ... jonos dori solbe = John started to drink

liga is a transitive verb and the O argument is usually filled by a location. For example ... jonos ligor london = John stays in London

However the object slot can be filled with a ![]() in which case liga means "to continue". For example ... jonos ligori solbe = John carried on drinking

in which case liga means "to continue". For example ... jonos ligori solbe = John carried on drinking

There is no verb liganau.

dwài is a transitive verb and the O argument is usually filled by a location. For example ... waulois fanfa dwura = The wolves are chasing the horse

However the object slot can be filled with a ![]() in which case dwài means "try". For example ... jonos dwora nyáu nambo = John is trying to go home

in which case dwài means "try". For example ... jonos dwora nyáu nambo = John is trying to go home

However when the subject of día and the maŋga subject are different then the verb gàu "to do" or "to make" must be used. For example ...

jonos gori jene solbe = John made Jane drink

jonos gori gò jene día solbes = John made/forced Jane to start to drink

[Note that is the above example, the maŋkas word order is set. That is jene día solbe is in a fixed order]

[Actually jonos gri jene día solbe is also expressible as jonos dainri jenen solbe. So we have two new verbs ... dianau and cuanau. Notice that Jane is in the dative case so these two new verbs are (V2)]

The engine dri doika = The engine started

Here doika "to walk" is a sort of dummy verb meaning to operate/run. It is necessary since día is a transitive verb.

..

The verb yái means "to have on your person" or perhaps "to have easy access to" if we are talking about a larger object. For example ...

jonos yór halma = John has an apple

As with all transitive verbs it has a passive form.

jono yawor = John is present

halma yawor hí jono = The apple is on John's person

yái is also used to show location.

ʔupais yór bode = "there are small birds in the tree" ... notice the ergative marking on ʔupai

[when location comes first yái is used with no pilana] ???

bode r ʔupaiʔe = "small birds are in the tree"

[when location comes last the copula and the general location pilana are used]

Usually an physical object is the O argument. But sometimes it is a maŋga. For example ...

yér gò flayon jodoi = You should feed the animals OR You ought to feed the animals

The above means that you have a weak obligation to feed the animals.

The negatives of the above are quite logical (unlike there English equivalents) ...

bù yér gò flayon jodoi = You don't have to feed the animals

yér jù flayon jodoi = You oughtn't to feed the animals .... maybe make gò droppable when you have jù

The verb byó means "to possess legally" to "own"

jenes byór wèu = Jane owns a car

And the passive form ...

wéu byowor hí jene = The car is owned by Jane

Usually an physical object is the O argument. But sometimes it is GC (gò-clause)

byér gò flayon jodoi = You have to feed the animals OR You must feed the animals

The above means that you have a strong obligation to feed the animals ... maybe it is your job.

The negatives of the above are quite logical (unlike there English equivalents) ...

bù byér gò flayon jodoi = You don't have to feed the animals

byér gò jù flayon jodoi = You mustn't feed the animals ... (kyà flayo jodoi would be used for a "here and now" situation)

'bù byér gò jù flayon jodoi = You can feed the animals if you want

(nús) gùr jono gò flayon jodoi = They make John feed the animals

byér gò gàun nù gò jono gàun flayon jodoi = you must make them make John feed the animals ????????====???????

Note on English usage (in fact all the Germanic languages) ... the way English handles negating modal words is a confusing. Consider "She can not talk". Since the modal is negated by putting "not" after it and the main verb is negated by putting "not" in front of it, this could either mean ...

a) She doesn't have the ability to talk

or

b) She has the ability to not talk

Note only when the meaning is a) can the proposition be contracted to "she can't talk". In fact, when the meaning is b), usually extra emphasis would be put on the "not". a) is the usual interpretation of "She can not talk" and if you wanted to express b) you would rephrase it to "She can keep silent". This rephrasing is quite often necessary in English when you have a modal and a negative main verb to express.

In béu a negative on the active verb and a negative on the maŋga is perfectly possible. This is shown below ...

jenes blrj flò cokolate => Jane can't eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability to eat chocolates) ... for example she is a diabetic and can not eat anything sweet.

jenes blr jù flò cokolate => Jane can not eat chocolates (Jane have the ability not to eat chocolates)... meaning she has the willpower to resist them.

jenes blrj jù flò cokolate => Jane can not not eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability, not to eat chocolates) ... meaning she can't resist them.

..

?? we use mas and loi loi ??? = others ???

slight obligation => might ???

obligation/duty => inevitability

physical ability => sometimes

..

anzu = duty

seŋgo = obligation

alfa = ability

hempo = permission or leave

hento = knowledge

..

..... The adverbs

There are 4 types of word that function as adverbs in béu.

1) There are adjectives which are changed into adverbs by suffixing -we. For example ...

saco = quick

sacowe = quickly

THIS type of adverbs can have any position within a sentence. However if they immediately follow the verb which they are qualifying, the suffix is deleted. For example ...

doikor saco nambon = doikor nambon sacowe = sacowe doikor nambon = she is walking quickly home

2) There are nouns which are changed into adverbs by suffixing -we. For example ...

deuta = soldier

deutəwe = "in the manner of a soldier"

Note that the final vowel in deuta changes here. This is because as well as being a suffix, wé is a noun in its own right meaning "way" or "method" (see the section on word building)

Just as saco is an adjective which is considered an adverb when immediately following a verb, so deutəwe is an adverb that is considered an adjective when immediately following a noun.

Also a noun is formed by suffixing -mi to the end.

deutəwemi = soldierliness

3) One of the functions of a nouns with pilana 1 => 8 + 15 is as an adverb. This type of adverb must follow the verb immediately. In a similar manner to type 2), if this form comes after a noun it is considered an adjective. For example ...

moŋgos flor halma pazbamau (the gibbon eats an apple on the table) pazbamau is an adjective describing where the apple is.

moŋgos flor pazbamau halma (the gibbon is eating an apple on the table) pazbamau is an adverb describing where the "eating" is taking place.

Note ... In English, the sentence "the monkey eats the apple on the table" is ambiguous.

Go thru the other pilana ???

4) This type of adverbs are nouns that are stand for time periods. For example tomorrow, yesterday, the past et. etc. Basically when they are not copula subjects, copula complements or in the ergative case, they are adverbs.

5) Words such as "often" ??? ( = many times ???) ... a particle ???

..

..... Quantity

... many, a lot

..

haì = many

haì bawa = many men

This word is only used with countable nouns. With un-countable nouns we use hè.

hè comes after the noun that it qualifies.

moze hè = a lot of water

hè also can qualify verbs and adjectives. As with normal adverbs, if it doesn't immediately follow the verb it must take the form hewe.

glá doikori hè = the woman has walked a lot

glá (rò) hauʔe hè = the woman is very beautiful

hewe glá doikori = the woman has walked a lot

..

... few, a little, a bit a little bit

..

uhai = few

uhe = a little

However a word meaning the same as uhe is iyo (also iyowe, when used as an adverb separated from the verb). iyo occurs twice as much as uhe.

hemai = amount, quantity .... there is no word *haimai

..

... to a greater degree

..

Appended to an adjective, ge indicates to a greater degree.

Appended to an adjective, mo indicates to the greatest degree.

When we have this sort of construction, we are usually comparing to people or things. The background person or thing has the pilana wo. For example ....

jene r jutuge jonowo = Jane is bigger than John

jene r jutumo = Jane is biggest

Note ... In English the words "more" (also "most", "less" and "least") can occur with multi-syllable adjectives. Also "more" can qualify nouns and verbs as well. The béu equivalent of "more" when qualifying nouns (non-countable) and verbs is hege. haige is used for countable nouns.

[ haige would translate Thai " ììk ", as in " ììk nɯɯŋ bìa " ]

..

... to a less degree

..

Also we have zo which indicates a lesser degree.

Plus we have zmo which indicated the least degree.

However the above two suffixes don't appear that often. The most common adjectives have polar forms. And it is usual to switch to the form which will allow you to express yourself using the ge or the mo suffix. But here is an example from an adjective that doesn't have a polar form.

dè r mutuzo = that one is not so important

dí r mutuzmo = this one is the least important

..

... to the same degree

..

As well as ge, mo, zo and zmo there is one more suffix that is appended to adjectives. It is la (note this is a pilana when appended to nouns)

jene r jutula jonowo = Jane is as big as John

jene r ʔes jutumi jonowo = Jane is as big as John

jene r uʔes jutumi jonowo = Jane is not the same size as John

..

... Antonym phonetic correspondence

..

In the above lists, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning from each other. However in béu there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | ai | |||

| f | e | |||

| b | eu | |||

| g | u | |||

| d | ua | high tone | ||

| l | =========================== | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ia | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | i | |||

| k | oi | |||

| p | o | |||

| t | au | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

Note ... The original idea of having a regular correspondence between the two poles of a antonym pair came from an earlier idea for the script. In this early script, the first 8 consonants had the same shape as the last 8 consonants but turned 180˚. And in actual fact the two poles of a antonym pair mapped into each other under a 180˚ turn.

An adjectives is called moizana in béu .... NO NO NO

moizu = attribute, characteristic, feature

And following the way béu works, if there is an action that can be associated with noun (in any way at all), that noun can be co-opted to work as an verb.

Hence moizori = he/she described, he/she characterized, he/she specified ... moizus = the noun corresponding to the verb on the left

moizo = a specification, a characteristic asked for ... moizoi = specifications ... moizana = things that describe, things that specify

nandau moizana = an adjective, but of course, especially in books about grammar, this is truncated to simply moizana

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences