Béu : Chapter 2 : The Verb: Difference between revisions

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

In the first person ... | In the first person ... | ||

'''doikas''' can be translated variously as "maybe I should walk", "should I walk ?", "how about me walking" | '''doikas''' can be translated variously as "maybe I should walk", "should I walk ?", "how about me walking", "may I walk" | ||

'''doikais''' = Let's walk ( urge.urge '''doikas''' = come on, lets walk ) | '''doikais''' = Let's walk ( urge.urge '''doikas''' = come on, lets walk ) | ||

| Line 247: | Line 247: | ||

That was the first person singular, in the second person the subjunctive is a very mild imperative. For example ... | That was the first person singular, in the second person the subjunctive is a very mild imperative. For example ... | ||

'''doikis''' can be translated variously as "maybe you should walk", "why don't you walk", "how about you walking" | '''doikis''' can be translated variously as "maybe you should walk", "why don't you walk", "how about you walking", "may you walk" | ||

And the third person ... | And the third person ... | ||

'''doikos''' = "how about you walking", "let him walk" | '''doikos''' = "how about you walking", "let him walk", "may he walk" | ||

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding '''ka'''. For example ... | The negative subjunctive is formed by adding '''ka'''. For example ... | ||

'''doikoska''' = best not to let him walk. ( lest he walk ??? is this right ?? ... we gave him money lest he starve to death )) | '''doikoska''' = best not to let him walk. ( lest he walk ??? is this right ?? ... we gave him money lest he starve to death )) | ||

(I gave him money to buy food .... I gave him money lest he be hungry) | |||

A third place where the subjunctive can turn up is in conditional sentences. Both verbs in a conditional sentence are in the subjunctive mood. | A third place where the subjunctive can turn up is in conditional sentences. Both verbs in a conditional sentence are in the subjunctive mood. | ||

<sup>*</sup>Of course you can add some doubt to the indicative by fronting the verb with the particle | <sup>*</sup>Of course you can add some doubt to the indicative by fronting the verb with the particle '''màs''' or '''lói'''. These particles are never added to any other mood. | ||

.. | .. | ||

Revision as of 02:57, 17 May 2015

..... The 5 verb forms

... The infinitive verb form

..

The infinitive is called the hipe

The most common multi-syllable verbs end in "a".

The less common multi-syllable verbs end in "e" or "o".

The least common multi-syllable verbs end in "au", "oi", "eu" or "ai".

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk

The infinitive can be regarded as a noun.

..

... The imperative verb form

..

The imperative is called the yeməpe

This is used for giving orders. When you utter an imperative you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action (although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible).

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

1) First the final vowel of the infinitive is deleted.

2) Then either -iya or -eya is added. iya when commanding one person, eya when commanding more than one person. For example ...

doikiya = walk !

For monosyllabic verbs ...

1) -ya is added. For example ...

dó = to do

doya = do it !

The negative imperative is formed by putting the particle kyà before the infinitive.

kyà doika = Don't walk !

There is no distinction for number in the negative imperative.

..

... The indicative verb form

..

The indicative is the most complicated verb form by far.

The indicative is called the hukəpe*

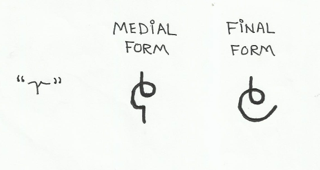

But first we must introduce a new letter.

..

..

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in the hukəpe.

So if you hear "r", you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

.. The doer

The first piece of information that must be given in the indicative is who does the action. To do this you first ...

1) Deleted the final vowel from the infinitive.

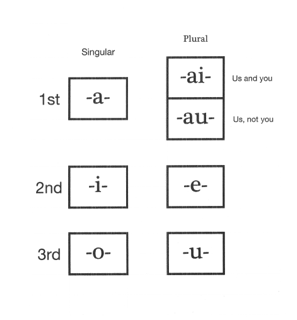

2) Then one of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer..

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikir = you walk

etc. etc. etc.

..

.. Tense

..

In béu tense is usually shown not on the verb but is indicated by an adverb of time. This adverb can come anywhere in a clause but it has a strong tendency to come clause initial.

YESTERDAY = yesterday I cleaned my car

THE DAY BEFORE YESTERDAY = the day before yesterday I cleaned my car

?? = I clean my car ... taken as a habitual in this case

TOMORROW = tomorrow I will clean my car

The words taiku meaning the past can be used instead of yesterday, the day before yesterday etc etc ??. This construction is equivalent to a past tense.

The words jauku meaning the future can simply be substituted for tomorrow ??. This construction is equivalent to a future tense.

To indicate the future, if the subject is human, often the word INTEND ??? is used. For example ... ??

Actually there is one tense in béu : the present tense which is shown by adding an "a". For example ...

doikara = I am walking

This tense is only used if the act is happening at the time of speaking. In contradistinction the English "-ing" suffix can turn up in time frames other than "now".

..

.. Aspect

..

The perfect aspect is shown by adding an "i". For example ...

doikari = I have walked

The ending "u" can be considered the opposite of the above aspect. Lets call it the "not yet" aspect. For example ...

doikaru = I have not yet walked / I have not walked

If you have plain doikar it will often be judged to have "habitual" aspect. This of course depends a lot on the context in which doikar occurs**.

The negative of the doikar form is doikarju

The -ra is only used for actions happening at the time of speaking. In English, the "to be - ing" construction is used for this. However the English "to be - ing" construction is also used to fit one action inside another. For example "she came in when I was shaving" ... usually set in the past but in the future is also possible. This is called the imperfect aspect (I think). In béu you use the copula plus the infinitive with the -n pilana affixed. For example ...

por kyu tar SHAVEn ... ( Side Note ... In this example, SHAVE is in what is uaually called the "imperfective" in the Western Linguistic Tradition, a form that combines tense and aspect)

Note ... SHAVEn is similar to an adjective in that it follows the copula. However it differs from an adjective in an important way ... it can never be an attribute of a noun. The form SHAVEana is the noun attribute.

...............XXX colour light green ................................

Note ... When you have the endings -ora, -ori and -oru they are always shortened to just -ra, -ri and -ru, provided the final consonant of the infinitive is not w y h or ʔ. For example ...

doikri = he has walked

...............XXX colour light green ................................

*The symbol for "r" is called huka (meaning "hook"). The word hukəpe actually means "R-form" by the normal rules of word building (mepe means form/shape).

**Different verbs have different likelihoods of being adjudged "habitual" when ending in "r". This likelihood is totally due to the internal semantics of the individual verb (which of course determine in which situations it is permissible to use the verb). ..

.. Negativeness

..

The indicative mood is negativized by adding ju. For example ...

doikarju = I do not walk

The present tense is negativized as above but with addition of the word ku.i ( meaning "now"). For example ...

doikarju ku.i = I am not walking

Note - the "u" aspect can be considered the negative of the "i" aspect and vice versa.

..

.. Probability

..

There are two adverbs màs and lói.

As with all adverbs they can be placed almost anywhere in a sentence. However these two have a strong preference to be sentence initial.

màs doikori = maybe he has walked

lòi doikori = probably he has walked

You could say that the first one indicates about 50 % certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty.

..

... The consecutive and simultaneous tenses ??

Earlier we mentioned the present tense. There are 2 further tenses in béu. However they aren't relative to NOW but relative to the last ROGER form verb.

The consecutive tense, eu, shows that the action takes place after the time of occurrence of the previous ROGER form verb. For example ...

jana doikar moʒi solbeu = Yesterday I had a walk and then drank some water

The simultaneous tense, ai, shows that the action takes place at the same time as the previous ROGER form verb. For example ...

jana doikar moʒi solbeu = Yesterday I walked about a bit while drinking water

Note ... verbs with these endings, even tho', they are in indicative mood, actually have the mood of the initial verb ???

..

... The subjunctive verb form

..

The subjunctive is called the sudəpe

The subjunctive verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "s".

Now the main thing about the subjunctive is that it is not "asserted" ... it is not insisted upon ... there is a shadow of doubt as to whether the action takes place ( or will take place.

This is in contradistinction to the indicative mood. In the indicative mood things definitely happen, there are no two ways about it *

There are a few places that the subjunctive turns up. First of all there are a set of leading verbs that always change there trailing verbs to the subjunctive. For example ....

"want", "wish", "prefer", "request/ask for", "suggest", "recommend", "be afraid", "demand/command", "let/allow", "advise", "forbid" etc.

Now the trailing clause in these sentences started of by the above verbs, can either have an initial bò (equivalent to one of the uses of "that") or not have an initial bò. But this makes no difference to the trailing verbs, they must all be in the subjunctive mood.

Note ... whether the tail clause starts with a bò or not, depends upon a number of things. But basically the more complex the tail clause is, the more likely you are to have bò.

Another place you see the subjunctive is when they are in stand alone clauses. Again the key thing to remember is "non-assertion". In this case it is almost as if the clause is a question, that is how far the non-assertion goes. The speaker wants to have a discussion with the listener about the proposition. For example ...

In the first person ...

doikas can be translated variously as "maybe I should walk", "should I walk ?", "how about me walking", "may I walk"

doikais = Let's walk ( urge.urge doikas = come on, lets walk )

That was the first person singular, in the second person the subjunctive is a very mild imperative. For example ...

doikis can be translated variously as "maybe you should walk", "why don't you walk", "how about you walking", "may you walk"

And the third person ...

doikos = "how about you walking", "let him walk", "may he walk"

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding ka. For example ...

doikoska = best not to let him walk. ( lest he walk ??? is this right ?? ... we gave him money lest he starve to death ))

(I gave him money to buy food .... I gave him money lest he be hungry)

A third place where the subjunctive can turn up is in conditional sentences. Both verbs in a conditional sentence are in the subjunctive mood.

*Of course you can add some doubt to the indicative by fronting the verb with the particle màs or lói. These particles are never added to any other mood.

..

... The subjunctive 2 verb form

..

he subjunctive 2 verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "si".

Now the main thing about the subjunctive 2 verb is that the action did not take place. However even tho' the action never happened, we still want to talk about the contingency ... we want to talk about "what might have been".

The subjunctive 2 verb form is made negative by the same method as the infinitive is made negative.

This is a different mood ( I guess ) needs a different name ??? How about calling them the "base form", "command form", "tell form", "do-able form" and the "non-do-able form". ..

..... Short verb

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an indicative, subjunctive or imperative verb form is to delete the final vowel from the infinitive. However this is only applicable for multi-syllabe words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different.

For a monosyllabic verbs the indicative endings and subjunctive suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive. For example ...

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ... swo.uske = lest they fear ...... etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ... etc. etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ... etc. etc.

dàu = to arrive

cái = to depart

..

The above is the general rules for short verbs, however the 37 short verbs below the rules are different.

Their vowels of the infinitive are completely deleted for the indicative and subjunctive verb forms. For example ...

myàr gì = I love you ........................ not * mye.ar gì

pòr nambo = he enters the house ... not *poi.or nambo

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to like, to love | ||

| yái = to have | |||

| jòi = to go | jwèu = to undergo, to bear, to endure, to stand | ||

| fà = to know | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

| bái = to ascend | byó = to be able to | blèu = to hold | bwá = to exit |

| gàu = to descend | glà = to store | gwói = to pass | |

| dó = to do | dwé = to come | ||

| lái = to change | |||

| cài = to use | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slè = to be under weak obligation | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kó = to see | kyò = to show | klói = to think | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyói = to be under strong obligation | plèu = to follow | |

| tèu = to put | twé = to meet | ||

| wàu = to lack | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to be good |

The imperative suffix is -ya for singular and plural for all short verbs. For example ...

nyauya nambo = go home !

swoya = fear !

gaiya = be in pain !

ʔauya ʃì = take it !

Some nouns related to the above ... yaivan = possessions, property, flovan = food, dovan = products, nauvan = tax, tribute, glavan = reserves, dó = things that must be done, dwái = deeds, acts, actions, behaviour.

A particle related to the above ... yú ... a particle that indicates possession, occurs after the "possessed" and before the "possessor.

..

..... The copula

..

There is one copula in beuba.

Its infinitive is sàu. Following the method of other verbs, its negative is jù sàu.

The indicative mood is derived from the infinitive in the usual method. So ...

sàr = I am

ʃìr = you are

sòr = he/she/it is

etc. etc.etc.

The negative is formed be suffixing -ke. For example ...

sorke = he/she/it is not

Actually the (present tense, positive) copula is usually dropped if there is no chance of a misunderstanding.

It is mostly used for emphasis; like when you are refuting a claim

Person A) ... ʃirke moltai = You aren't a doctor

Person b) ... sàr moltai = I AM a doctor

Another situation where the (present tense, positive) copula tends to be used is when either the subject or the copula complement are longish trains of words. For example ...

solbua alkyo ʔá dori sùr sawoi = Those alcoholic drinks that she has made are delicious.

Unlike the other verbs, the copula has a different form for the past tense and a different form for the future tense. These are ...

tàr = I was

jàr = I will be

jarke = I won't be

etc. etc.etc.

(You could say that taiku sàr => tàr and jauku sàr => jàr)

The forms ‘’’sor’’’ and ‘’’sur’’’ are invariably shortened to simply -‘’’r’’’ and stuck on to the end of the copula subject. ........................................XXX colour light green ................................

Similarly the forms ‘’’sorke’’’ and ‘’’surke’’’ are invariably shortened to simply -‘’’rke’’’ and stuck on to the end of the copula subject. ...............XXX colour light green ................................

Note ... In copular sentences there is not free word order. They must be "copula subject" followed by "copula" followed by "object". Copula subject does not take the ergative suffix -s.

The subjunctive forms are ...

sas and saske ... uses ???

There are only two imperative forms ... jiya and jeya

In a later chapter ...

tari = I was already

taru = I was not yet

sari = I am already

saru = I am not yet

jari = I will be already

jaru = I will not yet be

There are 2 more words that might be considered copulaa ...

1) twài = to be located, to be placed .... perhaps an eroded form of a participle of tèu "to place"

2) yór = to exist ... a third person indicative form of the verb yái "to have". The third person indicative meaning is completely bleached in this usage.

..

..... The Cardinal Numbers

..

béu has a unique word for every number from 1 up to 172710

For example ...

| ela | = 6 |

| icauva | = 7212 |

| idaiba | = 50312 |

| idaigauba | = 54312 |

| ulaigau | = 64012 |

..

These 1727 words are made up from smaller elements, using the duodecimal system. These smaller elements are shown in the table below ...

..

| 10012 = | ajai | 1012 = | ajau | one = | aja |

| 20012 = | uvai | 2012 = | uvau | two = | auva |

| 30012 = | ibai | 3012 = | ibau | three = | aiba |

| 40012 = | agai | 4012 = | ugau | four = | uga |

| 50012 = | idai | 5012 = | idau | five = | ida |

| 60012 = | ulai | 6012 = | ulau | six = | ela |

| 70012 = | icai | 7012 = | icau | seven = | oica |

| 80012 = | ezai | 8012 = | ezau | eight = | eza |

| 90012 = | okai | 9012 = | okau | nine = | oka |

| T0012 = | apai | T012 = | apau | ten = | iapa |

| E0012 = | atai | ............. E012 = | atau | ............ eleven = | uata |

Note ... I am using T to represent the number "ten", and E to represent the number "eleven".

To construct a number from the above ...

1) Select which elements you need. For example, for 54312, you will need the elements idai + ugau + aiba

2) If the element is non-initial, delete the initial vowel of the element => idai + gau + ba

3) And now, simply join the elements up => idaigauba

You will noticed that 12 numbers over eleven have been shortened. For example the "regular" form for 20 would be auvau, but this is actually uvau.

Also the number 6, ela has been shortened. This would have been eula if everything was perfectly regular.

..

..... The Ordinal Numbers & Fractions

..

To get an fractional number (regarded as specifiers ... as all numbers are) you just attach s- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| a unit | saja |

| a half | sauva |

| a third | saiba |

| a quarter | sida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

These are fully numbers. They are written in the same way as numbers, except the have a squiggle above them. The squiggle looks like an "8" on its side that hasn't fully closed.

..

To get an ordinal number (regarded as adjectives) you just attach n- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| first | naja |

| second | nauva |

| third | naiba |

| fourth | nida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of nò plus the number.

These forms are adjectives 100% and are always written out in full.

..

To get (I don't know what these are called) (regarded as a noun) you just attach b- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| alone, single | baja |

| a double, a twosome, a duality | bauva |

| a threesome, a trinity | baiba |

| a foursome, a quartet | bida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

Note bajai = lonely

..

..... The time of the day

dé = day

The béu day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called cuaju

The time of day is counted from cuaju. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called ajai (normally just called ajai, but cúa ajai or ajai yanfa might also be heard sometimes).

| 6 o'clock in the morning | cuaju |

| 8 o'clock in the morning | ajai |

| 10 o'clock in the morning | ufai |

| midday | ibai |

| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | agai |

| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | idai |

| 6 o'clock in the evening | ulai |

| 8 o'clock in the evening | icai |

| 10 o'clock at night | ezai |

| midnight | okai |

| 2 o'clock in the morning | apai |

| 4 o'clock in the morning | atai |

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon.

16:00 would be idai : 16:10 would be idaijau : 16:20 would be idaifau .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be idaitau

Now all these names have in common the element idai, hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called idaia (the plural of idai). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties".

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called cuajua. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time ajai was called ajaia(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time cuaju should be called cuajua. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial cuaju. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be cuaju ajau, "twenty past six" would be cuaju afau and so on.

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened idaia.pi

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them apaiʔe.

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued nàn ufau, for 2 hours : nàn ajai (nàn means "a long time")

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In béu they only have the yanfa. The yanfa is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as yanfa also.

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences