Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb: Difference between revisions

| Line 519: | Line 519: | ||

In the above example "teach" references 4 nouns. | In the above example "teach" references 4 nouns. | ||

.. | Usually it is easy to distinguish between "core arguments" which are essential and "peripheral arguments" which simply add more information. In the above example "English" can be dismissed as a peripheral argument. | ||

But what about "Jane". In the above example Jane's roll in the clause is defined by the prefix "to". But what if "John is teaching calculus to Jane in English" is re-arranged as "John is teaching Jane calculus in English"? Here you have three nouns not qualified by a prefix. In English "teach" is sometimes called a ditransitive verb (a verb that can take three essential arguments). | |||

In '''beu''' no verbs are considered ditransitive ... Jane will always have the dative '''pilana''' "n". This makes it easier to dismiss the dative argument as a "peripheral arguments". Now you might argue that every instance of teaching involves "somebody getting taught" ... well this is true, but it is also true that every instance of teaching involves some language being used. At the end of the day ... the English verb "teach" means exactly the same as its '''béu''' equivalent ( '''haun''' ). There are simple different conventions for talking about the verb in two different linguistic traditions. The '''béu''' linguistic tradition is the simplest. | |||

.. | The '''béu''' linguistic tradition divides all verbs in into two types .... H (transitive) and Ø (intransitive). Usually in dictionaries just marked by the simbol H or Ø. A transitive verb is called a "stroke verb" and an "intransitive verb" is called a dash verb. | ||

A verb is H if it can in any instance take a noun with the "s" '''pilana'''. | |||

A verb is Ø if it never take a noun with the "s" '''pilana'''. | |||

.. | .. | ||

Now I will introduce the S A O convention which was introduced by RMW Dixon and is useful cross-linguistically for talking about valency. This is a useful way to refer to the arguments of transitive and intransitive verbs. The one argument of the intransitive verb is called the S argument. The argument of the transitive verb in which the success of the action most depends is referred to as the A argument. The argument of of the transitive verb is most affected by the action is called the O argument. | |||

O was probably chosen from "object", A from "agent" and S from "subject" ( I find this useful to keep in mind as a memory aid). However O does not "mean" object and A does not mean agent and S does not mean subject. I (and many other linguists) use the word subject to refer to either A or S. Easier to talk about "subject" that to talk about "A or S" all the time. | |||

.. | The '''béu''' equivalents of A argument is "the '''sadu''' noun", of the O argument ... "the dash noun", and the S argument ... "the stroke noun". | ||

.. | .. | ||

Now in English certain verbs appear to be Ø in some situations and H in others. These are called ambitransitive verbs. | |||

.. | .. | ||

1) The old woman knitted a sweater | |||

2) The old woman knitted | |||

"knit" is regarded as a "A=S ambitransitive". In (1) "old woman" is S ... in (2) "old woman" is S. Both clauses describe essentially the same scene. | |||

.. | .. | ||

3) The old woman opened the door | |||

4) The door opened | |||

"open" is regarded as a "O=S ambitransitive". In (3) "the door" is O ... in (2) "the door" is S. Both clauses describe essentially the same scene. | |||

.. | .. | ||

Now just as there are no "ditransitives" in '''béu''', there are no "ambitransitives. "knit" is considered H but with the O argument being dropped when it is unimportant or unknown. Similarly "open" is considered H but with the A argument dropped'''*''' when it is unimportant or unknown. Well "open" always H in '''béu''' ... not so in English ... in "the door closed" "the door" is subject because it comes before the noun. And as only argument, that argument is S. In '''béu''' ... '''pintu mapəri''' means "the door opened" or "the door was opened". We know '''mapa''' "to open" is H becuse it can occur with A arguments ( '''sadu''' nouns ). However in this case the only noun is not marked for the ergative hence it must be the O argument. | |||

'''*'''Actually it would be possble to drop A arguments in English if the imperative was not the base verb. For example in English "knit a jersey" is a command ... but if English ... say ... suffixed a "ugu" for the imperative, then the command would be "knltugu a jersey". That would allow "knit a jersey" to be interpreted as "jersey being knitted". | |||

.. | .. | ||

So in '''béu''' …. each verb is either H or Ø … no ambitransitives or ditransitives. | |||

Also “the passive” is not talked about … rather it is just considered a particular case of “dropping”. And actually “dropping” is not considered a bit deal … just an very obvious thing to do. | |||

.. | .. | ||

Now one problem with dropping arguments is that the subject (S or A) must be represented in slot "1" of the indicative verb. How should we know what to put in here ( see Ch3.1.2.1 ). Well we could use the 3 person plural suffix -'''u'''- ... chances are that it is a 3rd person agent and the plural is more generic than the singular. This is what Russian does to make a sort of a passive. '''béu'''s solution is to use a schwa. We don't know which of the 7 markings for person to use ... so everything sort of collapses in ... to the schwa ... an impersonal schwa. | |||

.. | .. | ||

| Line 631: | Line 605: | ||

.. | .. | ||

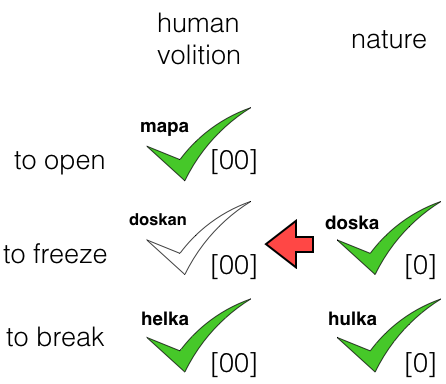

Now "door" is a man-made object and probably it exists in a place with many people around. So it is reasonable to expect there to be ''human volition'' involved when it opens. But what about when we get out into nature. When we see a river freezing. There is no agent to be seen behind this "freezing" ... it just happens. For this reason the verb "to freeze" '''doska''' is | Now "door" is a man-made object and probably it exists in a place with many people around. So it is reasonable to expect there to be ''human volition'' involved when it opens. But what about when we get out into nature. When we see a river freezing. There is no agent to be seen behind this "freezing" ... it just happens. For this reason the verb "to freeze" '''doska''' is Ø. | ||

But now we have become clever ... we hold dominion over nature. Hence we need to derive a word for freeze that is [00]. And that deriration is arrived at by appending -'''n''' (historically this was -'''nau''' and even further back it was the independent word '''náu''' "to give") | But now we have become clever ... we hold dominion over nature. Hence we need to derive a word for freeze that is [00]. And that deriration is arrived at by appending -'''n''' (historically this was -'''nau''' and even further back it was the independent word '''náu''' "to give") | ||

| Line 643: | Line 617: | ||

.. | .. | ||

Actually any | Actually any Ø can take this suffix and become H. Here are a few more examples ... | ||

.. | .. | ||

| Line 691: | Line 665: | ||

.. | .. | ||

Six | Six H can also take -'''nau''' as well. They are ... | ||

.. | .. | ||

| Line 728: | Line 702: | ||

.. | .. | ||

In English, all the above except the last would be considered ditransitive verbs. "to take out" would not be considered ditransitive because one argument would be marked by the preposition "from" | |||

(Note : '''fyá''' "to tell" means basically the same as '''glùn''' but is less formal ) | (Note : '''fyá''' "to tell" means basically the same as '''glùn''' but is less formal ) | ||

| Line 733: | Line 709: | ||

.. | .. | ||

We have discussed '''mapa''' and '''doska''' so far. The first is considered basically | We have discussed '''mapa''' and '''doska''' so far. The first is considered basically H and the second one basically Ø. There is a third type of verb ... for this type it is hard to say if it is more basic as Ø or more basic as H. So these verbs have <u>two</u> basic forms. For example ... | ||

.. | .. | ||

| Line 753: | Line 729: | ||

.. | .. | ||

There are about 40 of these pairs. If the | There are about 40 of these pairs. If the Ø has '''u''' the H will have '''e''' ... if the Ø has '''i''' the H will have '''o'''. | ||

So lets summarize these three typre of verb ... | So lets summarize these three typre of verb ... | ||

| Line 767: | Line 743: | ||

So to wrap it all up about verbs and arguments ... | So to wrap it all up about verbs and arguments ... | ||

No verbs are ambitrasitive. They are either | No verbs are ambitrasitive. They are either Ø or H. However it is easy to drop the A or the O argument from a [00] clause if either of them is considered trivial or is unknown. | ||

Now in '''béu''' any | Now in '''béu''' any H can be given a Ø meaning ( grammatically the structure is still H ) by making the the O argument '''tí''' ... meaning himself, herself, yourself etc. etc. However only animate A arguments do this. Hence ... | ||

'''bàus tí timpori''' = the man hit himself ................. acceptable | '''bàus tí timpori''' = the man hit himself ................. acceptable | ||

| Line 803: | Line 779: | ||

The above method of presenting a verb like '''mapa''' all hint at human volition. To get rid of this connotation (to suggest that the event happened naturely) we must use '''lài''' "to become" plus an adjective. This is demonstrated below ... | The above method of presenting a verb like '''mapa''' all hint at human volition. To get rid of this connotation (to suggest that the event happened naturely) we must use '''lài''' "to become" plus an adjective. This is demonstrated below ... | ||

Consider '''geuko''' = "to turn green" ... | Consider '''geuko''' = "to turn green" ... H ... derived from '''gèu''' "green" | ||

| Line 814: | Line 790: | ||

.. | .. | ||

Now consider '''mapa''' = "to open" ... | Now consider '''mapa''' = "to open" ... H | ||

Revision as of 11:53, 4 June 2017

... The Verbal Moods

..

When people speak they have different intentions. That is they are trying to achieve different things by speaking ... maybe they are trying to convey information, or wanting somebody to do something, or not to do something, or they are just expressing their feelings about something. All these are examples of what is called moods. Different languages have different methods of coding their moods. Also the various moods of a languages cover a different semantic range compared to other languages.

There are 7 moods in béu ... 3 expressing themselves by changes to the root verb and 4 by periphrasis.

..

..

..

What are considered moods are shown by a green circle.

..

..

How the different moods and forms interact are shown above. [this will be explained in full later]

..

... The Infinitive

..

The maŋga is "the infinitive"

This is the base form of the verb ... not considered a mood. maŋga corresponds to what is called the "infinitive" in some languages or the "masDar" in Arabic.

About 32% of multi syllable maŋga end in "a".

About 16% of multi syllable maŋga end in "e", and the same for "o".

About 9% of multi syllable maŋga end in "au", and the same for "oi", "eu" and "ai".

Note that no maŋga end in "i", "u", "ia" and "ua"

"i" is reserved for marking verb chains, which will be explained later.

"u" is used for the imperative mood ... i.e. for commanding people.

"ia" is used for a past passive participle. For example ...

yubako = to strengthen

yubakia = strengthened ... as in pazba dí r yubakia => "this table is strengthened"

"ua" could be called the future passive participle I guess. For example ...

ndi r yubakua => these ones must be strengthened

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk .... not to walk

..

... The indicative

..

Also called the R-form.

..

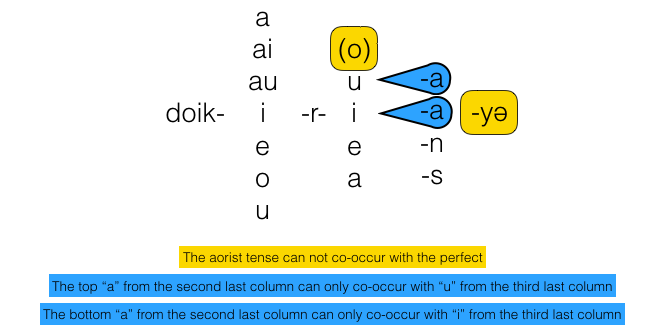

To make a verb in the indicative mood, you must first deleted the final vowel from the infinitive. Then add affixes that indicate "agent", "indicative mood", "tense", "evidentiality" and "perfectness". We will refer to these as slots 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 respectively.

..

.. Slot 1

..

Slot 1 is for the agent ..

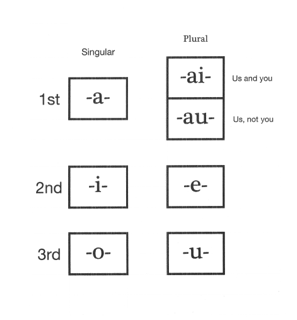

One of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer..

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikair and doikaur = we walk

doikir = you walk

doiker = you walk

doikor = he/she/it walks

doikur = they walk

..

.. Slot 2

..

Slot 2 is for the indicative mood marker.

..

At this point we must introduce a new sound and a new letter.

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such. It only occurs in grammatical suffixes and it indicates the indicative mood.

If you hear an "r" you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

..

.. Slot 3

..

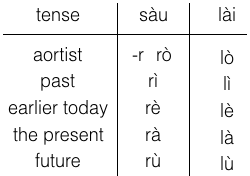

Slot 3 is for tense markers. There are 5 tense markers in béu

..

1) *doikaro => doikar = I walk (habitually)

| tunheu-n | doik-a-r-∅ | fafalaja | gò | nambo-n | ny-á-r-∅ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| align=center|walk-1SG-IND-AOR | "every afternoon" | CONJ | home-DAT | return-1SG-IND-AOR |

==> I walk to the townhall every afternoon and then return home

I call this the aortist tense. The word comes from Ancient Greek and means "indefinite" as it was the unmarked tense/aspect. (Actually thIs unmarked form had a past & nondurative meaning in Ancient Greek). I call this form aortist because it is usually represented by a null morpheme. In béu it has a sort of timeless tense (sometimes it is habitual) used for generic statements. For example ...

pyár jwadoi = "birds fly"

Actually you can say this tense has an underlying o which appears if there is an n or an s in the evidentiality slot.

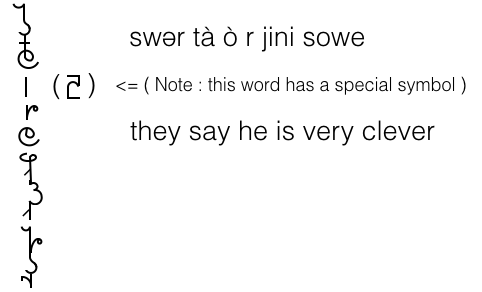

| tunheu-n | doik-o-r-o-s | fafalaja | gò | nambo-n | ny-o-r-o-s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| align=center|walk-3SG-IND-AOR-EV2 | "every afternoon" | CONJ | home-DAT | return-3SG-IND-AOR-EV2 |

==> They say he/she walks to the townhall every afternoon and then returns home

2) doikaru = I will walk

This is the future tense

3) doikari = I walked

This is the past tense. This means that the action was done before today (by the way ... the béu day starts at 6 in the morning).

4) doikare = I walked

This is the near-past tense. This means that the action was done earlier on today (a good memory aid is to remember that e is the same vowel as in the English word "day")

5) doikara = I am walking

This is the present tense ... it means that the action is ongoing at the time of speaking.

..

It can be seen that béu is more fine-grained, tense-wise than most of the world's languages ... http://wals.info/chapter/66 and http://wals.info/chapter/67

..

.. Slot 4

..

Slot 4 can have one of the evidential markers a, a, n, s or it can be empty. Actually the first a defines the subjects attitute rather than any evidentiality, however all 4 are usually just called evidential markers.

..

There are three markers that cites on what evidence the speaker is saying what he is saying. However it is not mandatory to stipulate on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In fact most occurrences of the indicative verb do not have an evidence marker.

The markers are as follows ...

1) -n

For example ... doikorin = "I guess that he walked" ... That is the speaker worked it out from circumstances/clues observed.

2) -s

For example ... doikoris = "They say he walked" ....... That is the speaker was told by some third party(ies) or overheard some third party(ies) talking.

3) -a

For example ... doikoria = "he walked, I saw him" ...... That is the speaker saw it with his own eyes.

Note that the above evidential only co-occurs with the past tense and near-past tense. Actually when used with the near-past tense, *ea => ia so the distinction between "past" and "near-past" is lost for this evidential.

Now there is a forth possibility for this slot ... and it is not actually an evidintial. Furthermore it has the same form as 3).

4) -a

For example ... doikorua = "he intends to walk" ... the agent in this case must be a sentient being of course.

This evidential marker only co-occurs with the future tense.

If the speaker doesn't know the evidential or deems it unimportant then this slot can be left empty. According to corpus studies in béu, 60% - 70% of r-form have nothing in this slot.

..

It can be seen that the béu evidentiality inventory is quite substantial compared to other languages ... http://wals.info/chapter/78

..

.. Slot 5

..

This slot can have the "perfect aspect marker" yə or it can be empty.

..

The perfect tense, logically doesn't differ that much difference from the past tense,. but it is emphasizing a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this aspect in English and it is realized as "have -en".

For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch, this emphasizes the absence of John as opposed to "he went for lunch". The latter is just an action that happened in the past, the former is a present state brought about by a past action.

For another example ... "she read the book on geometry"

This doesn't specify whether she read it all the way thru or whether she just read a bit of it. Whereas ...

"she has read the book on geometry", implies she read the book all the way thru, but more importantly the connotation is that at the present time she has knowledge of geometry.

The total verb suffix system is given below.

..

..

The aortist tense can not occur with the perfect. It may appear that it does though. This is because the a of the present tense is dropped if yə is appended directly on to it. So ...

doikora = He is walking

doikoras = The say I am walking

doikoryə = He has walked ... or to be more specific ... "from the beginning of time until now he has walked at least once"

doikorasyə = The say he has walked

The perfect marker -yə was probably derived from ìa "to finish/to complete" in its verb chain form. The perfect aspect occurs in roughly half of the languages of the world ... http://wals.info/chapter/68

Also it appears that 5 categories being appended to the verb is typical of languages of the world. See ... http://wals.info/chapter/22 [If I have understood the chapter properly]

..

... The imperative

..

You use the following forms for giving orders ... for giving commands. When you use the following forms you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action ... although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible.

..

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

The final vowel of the maŋga is deleted and replaced with u.

doika = to walk

doiku = walk !

..

For monosyllabic verbs -hu is appended.

gàu = "to do"

gauhu = "do it" ... often só is added fot extra emphasis.

só gauhu = do it !

One verb has an irregular form.

jò = "to go"

ojo = "go" ... actually a bit abrupt, probably expressing exasperation, veering towards "fuck off" ... jò itself can be used as a very polite form.

..

The imperative cab be directed at second person singular or second person plural. When addressing a group and issuing a command to the entire group you sort of let your eyes flick over the entire group. When addressing a group and issuing a command to one person you keep your eyes on this person when issuing the command ... maybe saying their name before the command ... probably preseded by só which is a vocative marker as well as being an emphatic particle.

[ Note ... I think that in English, the infinitive usually has "to" in front of it, in order to distinguish it from the imperative. In béu too there is a need to distinguish between these two verb forms. However as the imperative occurs less often than the infinitive, I have decided to mark the imperative. ]

..

... The prohibitive

..

This is also called the negative imperative. Semantically it is the opposite of the imperative. It is formed by putting the particle kyà before maŋga.

kyà doika = don't walk

That is pretty much all there is to say about it.

..

... The optative

..

This form expresses a wish or hope of the speaker ... but there is no appeal for the addressee to act. Also it is not really giving information as such. It is more about letting the speaker express his emotions [ maybe "ventative would be a suitable name for it :-) ]

The form is introduced by the particle fò. This particle has no other uses. It always comes utterance initial.

It expresses wishful thinking. For example ... fò blèu doika = "Oh to be able to walk" ... fò sàu jini = "I wish I was clever"

This form is used for curses and benedictions ... by frequency of usage the former outnumber the latter by about 10 to 1. For example ...

fò gò diablos ò ʔaworu = "May the Devil take him"

There are some formula type expressions that are used in certain situations/ rituals that use this form.. For example xxx = "God save the king"

The most common use of fò is the greeting fò fales sàu gipi "may peace be upon you"

The verb form in this construction is usually maŋga. Most often hopes and wishes are for the future, but sometimes they are orientated towards the past (I suppose they should be called regrets in these cases). For example ...

"If only you had arrived yesterday"

In these cases the R-form is used after the particle gò.

"If only you had arrived yesterday" => fò gò diriyə jana

The table below shows the optative construction ... either with the particle fò plus maŋga OR with the particles fò gò plus the R-form.

..

... The suggestive

..

We have come across kái before. In chapter 2.10 we saw that it was a question word meaning "what kind of". It normally follows a noun being an adjective. For example ...

báu kái = what type of man ?

ò r báu kái = what type of man is he ?

ò r deuta kái = what type of soldier is he ?

nendi kái = this is what type ?

But just as a normal adjective can be a copula complement, so can kái.

ò r kái = what type is he ?

nendi r kái = this is what type ?

ʃì r kái = what type of thing is it ?

However when you see kái utterance initial you know that it has a slightly different function : it is introducing the "soliciting opinion" mood. For example ...

kái wìa nyáu nambon jindi = How about we go home now ? OR Let's go home now.

Now ... as with the "optative", the "soliciting opinion" mood is usually orientated towards the future and uses maŋga. However their are circumstances where you solicit opinion about past events [for example a group of detectives on a crime scene discussing the possible steps taken by the perpetrator]. In these circumstances the R-form would be used preceded by the particle tà ... [see the table in the section above]

The main thing about this mood is that the speaker is asking for feedback/advice/approval or disapproval. But it overlaps with the field "gently suggesting a course of action" somewhat.

..

... The interrogative

..

Also called Polar Questions. A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

..

To turn a normal statement ( i.e. with the verb in its R-form) into a polar question the particle ʔai? is stuck on at the very end.

It has its own symbol (and I transcribe it as ʔai?) because it possesses its own tone contour.

I have mentioned this particle in chapter 1 (if you look back you can see its exact tone contour). Here is its symbol again ...

And here is an example of it in action ...

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

... jono jaŋkori ʔai? = Did John run ?

..

ʔai? is neutral as to the response expected ... well at least in positive questions.

To answer a positive question you answer ʔaiwa "yes" or aiya "no" (of course if "yes" or "no" are not adequate, you can digress ... the same as any language).

Here is an example of a positive question ...

glá r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman beautiful ?

If she is beautiful you answer ʔaiwa, if not you answer aiya*.

..

To answer a negative question it is not so simple. ʔaiwa and aiya are deemed insufficient to answer a negative question on their own. For example ...

glá bù r hauʔe ʔai? = Is the woman not beautiful ?

If she is not beautiful, you should answer bù hauʔe**, if she is you can answer either hù hauʔe or glá r hauʔe

I guess a negative question expects a negative answer, so a positive answer must be quite accoustically prominent (that is a short answer ("yes" or "no") is not enough)

..

We have mentioned só already ... in the above section about seŋko. This is the focus particle. It has a number of uses. When you want to emphasis one word in a clause, you would stick hù in front of it***.

Another use for só is when hailing somebody .... só jono = Hey Johnny

You can also stick it in front of someone's name when you are talking to them. However it is not a "vocative case" exactly. Well for one thing it is never mandatory. When used the speaker is gently chiding the listener : he is saying, something like ... the view you have is unique/unreasonable or the act you have done is unique/unreasonable. When I say unique I mean "only the listener" hold these views : the listener's views/actions are a bit strange.

When stuck in front of a non-multi-syllable verb you get an imperative. For example ... só nyáu = Go home

só can also be used to highlight one element is a statement or polar question. For example ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement ... bàus só glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers.****

Unfocused question ... bàus glán nori alha ʔai? = Did the man give flowers to the woman ?

Focused statement ... bàus só glán nori alha ʔai? = It is to the woman that the man gave flowers ?

..

Any argument can be focused in this way.

..

*These words have a unique tone contour as well ... at least when spoken in isolation. I suppose I should have given these two words a symbol each ... if I wanted to be consistent.

**Mmm ... maybe you could answer ʔaiwa here ... but a bit unusual ... not entirely felicitous.

***In English, when you want to emphasis a word, you make it more accoustically prominent : you don't rush over it but give it a very careful articulation. This is iconic and I guess all languages do the same. It is a pity that there is no easy way to represent this in the English orthography apart from increasing the font size or adding exclamation marks.

****English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to an element in a clause.

..

The other type of question ... the content question was covered in the last chapter.

..

... The conflative

..

Also called the i-form. [By the way "conflative" is my term ... I thought I would join in the fun and make up a silly name myself]

I will only touch on this here. Nearer the end of this chapter there is a section that goes into this in a lot more detail. OK one quick example ...

to walk = doika

road = komwe

to follow = plèu

to whistle = wiza

From the above we could make three short sentences.

John walked => jono doikori

John followed the road => jonos komwe plori

John whistled => jono wizori

..

However as all three verbs seem to take part in the same action they can be combined. The first verb in the combination is normal (whether it is r-form, u-form, s-form or in fact manga).

The following verbs in the combination take a special ending ... -i for multi-syllable words and the schwa ə for mono-syllable words. So we get the form ...

John walked along the road whistling => jono doikori komwe plə wiʒi

..

..... Verbs & Valency

..

In every language a verb usually references a number of nouns ... usually called arguments. For example ....

| jono-s | jene-n | laigau | haun-o-r-a | eŋglaba-tu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John-ERG | Jane-DAT | calculus | teach-3SG-IND-PRES | English-INST |

==> John is teaching calculus to Jane in English

In the above example "teach" references 4 nouns.

Usually it is easy to distinguish between "core arguments" which are essential and "peripheral arguments" which simply add more information. In the above example "English" can be dismissed as a peripheral argument. But what about "Jane". In the above example Jane's roll in the clause is defined by the prefix "to". But what if "John is teaching calculus to Jane in English" is re-arranged as "John is teaching Jane calculus in English"? Here you have three nouns not qualified by a prefix. In English "teach" is sometimes called a ditransitive verb (a verb that can take three essential arguments).

In beu no verbs are considered ditransitive ... Jane will always have the dative pilana "n". This makes it easier to dismiss the dative argument as a "peripheral arguments". Now you might argue that every instance of teaching involves "somebody getting taught" ... well this is true, but it is also true that every instance of teaching involves some language being used. At the end of the day ... the English verb "teach" means exactly the same as its béu equivalent ( haun ). There are simple different conventions for talking about the verb in two different linguistic traditions. The béu linguistic tradition is the simplest.

The béu linguistic tradition divides all verbs in into two types .... H (transitive) and Ø (intransitive). Usually in dictionaries just marked by the simbol H or Ø. A transitive verb is called a "stroke verb" and an "intransitive verb" is called a dash verb.

A verb is H if it can in any instance take a noun with the "s" pilana.

A verb is Ø if it never take a noun with the "s" pilana.

..

Now I will introduce the S A O convention which was introduced by RMW Dixon and is useful cross-linguistically for talking about valency. This is a useful way to refer to the arguments of transitive and intransitive verbs. The one argument of the intransitive verb is called the S argument. The argument of the transitive verb in which the success of the action most depends is referred to as the A argument. The argument of of the transitive verb is most affected by the action is called the O argument.

O was probably chosen from "object", A from "agent" and S from "subject" ( I find this useful to keep in mind as a memory aid). However O does not "mean" object and A does not mean agent and S does not mean subject. I (and many other linguists) use the word subject to refer to either A or S. Easier to talk about "subject" that to talk about "A or S" all the time.

The béu equivalents of A argument is "the sadu noun", of the O argument ... "the dash noun", and the S argument ... "the stroke noun".

..

Now in English certain verbs appear to be Ø in some situations and H in others. These are called ambitransitive verbs.

..

1) The old woman knitted a sweater

2) The old woman knitted

"knit" is regarded as a "A=S ambitransitive". In (1) "old woman" is S ... in (2) "old woman" is S. Both clauses describe essentially the same scene.

..

3) The old woman opened the door

4) The door opened

"open" is regarded as a "O=S ambitransitive". In (3) "the door" is O ... in (2) "the door" is S. Both clauses describe essentially the same scene.

..

Now just as there are no "ditransitives" in béu, there are no "ambitransitives. "knit" is considered H but with the O argument being dropped when it is unimportant or unknown. Similarly "open" is considered H but with the A argument dropped* when it is unimportant or unknown. Well "open" always H in béu ... not so in English ... in "the door closed" "the door" is subject because it comes before the noun. And as only argument, that argument is S. In béu ... pintu mapəri means "the door opened" or "the door was opened". We know mapa "to open" is H becuse it can occur with A arguments ( sadu nouns ). However in this case the only noun is not marked for the ergative hence it must be the O argument.

*Actually it would be possble to drop A arguments in English if the imperative was not the base verb. For example in English "knit a jersey" is a command ... but if English ... say ... suffixed a "ugu" for the imperative, then the command would be "knltugu a jersey". That would allow "knit a jersey" to be interpreted as "jersey being knitted".

..

So in béu …. each verb is either H or Ø … no ambitransitives or ditransitives. Also “the passive” is not talked about … rather it is just considered a particular case of “dropping”. And actually “dropping” is not considered a bit deal … just an very obvious thing to do.

..

Now one problem with dropping arguments is that the subject (S or A) must be represented in slot "1" of the indicative verb. How should we know what to put in here ( see Ch3.1.2.1 ). Well we could use the 3 person plural suffix -u- ... chances are that it is a 3rd person agent and the plural is more generic than the singular. This is what Russian does to make a sort of a passive. béus solution is to use a schwa. We don't know which of the 7 markings for person to use ... so everything sort of collapses in ... to the schwa ... an impersonal schwa.

..

"the door opened" => "the door was opened" = pintu mapəri (Actually I do not think the schwa symbol is distinct enough ... from now on I will use a dash) => pintu map-ri

..

Here are some examples of this construction [ I will call it the schwa construction from now on ]

beuba sw-r dían = "The language of béu is spoken here"

pí gaudoheu dè_sweno g-r = "In this factory telephones are made"

toilia bù ost-r pí duka dí = "Books are not sold in this shop"

pintu by-ru mapa = pintu r mapua = the door has to be opened

pintu bl-r mapa = the door can be opened ........... [ to understand this example and the one above it ... see Ch 4.7 ]

hala dè nyal-ryə = that rock is eroded .......... nyale = to erode, to wear

..

Note ... the schwa can not support any tone. And as it is only used in the grammer and not in any base words as such it was not introduced in Chapter 1 (as r was not). The schwa is in fact a cross ...

Also note ... Some people pronouns "schwa" + "syllable final rhotic" as "ø". These people also tend to give "ø" the proper tone. However the majority pronoun a schwa followed by a rhotic appoximant with neutral tone.

..

Now "door" is a man-made object and probably it exists in a place with many people around. So it is reasonable to expect there to be human volition involved when it opens. But what about when we get out into nature. When we see a river freezing. There is no agent to be seen behind this "freezing" ... it just happens. For this reason the verb "to freeze" doska is Ø.

But now we have become clever ... we hold dominion over nature. Hence we need to derive a word for freeze that is [00]. And that deriration is arrived at by appending -n (historically this was -nau and even further back it was the independent word náu "to give")

Hence ...

moze doskori = the water froze

moze doskaniri = You froze the water

..

Actually any Ø can take this suffix and become H. Here are a few more examples ...

..

| pyà | to fly | pyàn | to throw |

| jó | to go | jón | to send |

| tè | to come | tèn | to summon |

| bái | to rise | báin | to raise |

| kàu | to descend | kàun | to lower |

| dài | to die | dàin | to kill |

| slài | to change | slàin | to change |

| diadia | to happen | diadian | to cause |

..

Six H can also take -nau as well. They are ...

..

| flò | to eat | flòn | to feed |

| bwí | to see | bwín | to show |

| háu | to learn | háun | to teach |

| glù | to know | glùn | to inform |

| pòi | to enter, to join | pòin | to put in |

| féu | to exit, to leave | féun | to take out |

..

In English, all the above except the last would be considered ditransitive verbs. "to take out" would not be considered ditransitive because one argument would be marked by the preposition "from"

(Note : fyá "to tell" means basically the same as glùn but is less formal )

..

We have discussed mapa and doska so far. The first is considered basically H and the second one basically Ø. There is a third type of verb ... for this type it is hard to say if it is more basic as Ø or more basic as H. So these verbs have two basic forms. For example ...

..

cwamo hulkori = the bridge broke

deutais cwamo helkuri = the soldiers broke the bridge

..

Actually for the first example .. the chances are that the breakage was due to wear and tear caused by human activity. But the important thing is that it is non-volitional. Also there might have been no humans around when the bridge actually did break. So we can talk about the bridge breaking by itself ... as if by an act of nature. And another example ...

..

jono wiltore = John woke up (earlier today)

jenes jone woltore = Jane woke up John (earlier today)

..

There are about 40 of these pairs. If the Ø has u the H will have e ... if the Ø has i the H will have o.

So lets summarize these three typre of verb ...

..

..

So to wrap it all up about verbs and arguments ...

No verbs are ambitrasitive. They are either Ø or H. However it is easy to drop the A or the O argument from a [00] clause if either of them is considered trivial or is unknown.

Now in béu any H can be given a Ø meaning ( grammatically the structure is still H ) by making the the O argument tí ... meaning himself, herself, yourself etc. etc. However only animate A arguments do this. Hence ...

bàus tí timpori = the man hit himself ................. acceptable

*pintus tí mapori = the door opened itself ...... unacceptable

In English there are two ways to report on a door opening without mentioning any agent ... "the door opened" and "the door was opened"

In béu only one ... pintu map-ri ... which is just a two place clause with the A argument dropped. Comparable to how "the old woman knitted" is a two place clause with the O argument dropped.

..

In béu you can make a passive participle by suffixing -ia.

If you come across something broken and you know it was broken by human volition ... you would call it helkia.

If you come across something broken and you did not know how it was broken ... you would call it hulkia.

If you come across something frozen you would call it doskia. There is no such word as *doskania.

..

In béu you can make the so called obligation participle by suffixing -ua.

If you come across something that had to be broken ... you would call it helkua.

If you come across something that had to be frozen ... you would call it doskanua.

There is no such words as *doskua or *hulkua

..

The above method of presenting a verb like mapa all hint at human volition. To get rid of this connotation (to suggest that the event happened naturely) we must use lài "to become" plus an adjective. This is demonstrated below ...

Consider geuko = "to turn green" ... H ... derived from gèu "green"

1) báu lí gèu = The man became green .. ........................ natural

2) báu geuk-ri = The man was made green .................... human volition

3) báus tí geukori = The man made himself green

..

Now consider mapa = "to open" ... H

1) pintu lì mapia = the door became opened = the door opened .......... natural ................ [ here the agent could be anything ... the wind ... or even some fairy cái ... use your imagination ]

2) pintu map-ri = the door was opened ............................................... human volition .... [ this one implies that the agent was human but is either unknown or unimportant and the action deliberate ]

Note ... there is no (3) here as a door is non-human.

..

In either of the (1)'s wistia "deliberately/carefully" or wistua "accidently/carelessly" can be added after* lì. This automatically makes Agent => Human

The same for the (2)'s, but the incidence of wistua should greatly excede the incidence of wistia as "intention" is the default for this construction.

With (3) the connotation of intent is so strong that wistia/ wistua could be considered a bit infelicitous ... not impossible but indicative of a very unusual situation.

* or wistiwe or wistuwe if not immediately after the verb. [by the way ... wisto = mind/brain]

..

..... Short Verbs

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an R-form is to delete the final vowel from the maŋga. However this is only applicable for multi-syllable words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different. For monosyllabic verbs the R-form suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive.

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ...

Many béu speakers pronounce a glottal stop between the two parts, especially if they are speaking forcefully.

In my transcription a dot is inserted between the base and the suffixes. In the béu writing system the two vowels are simple written alongside.

..

..

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the R-form.

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ...

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the R-form.

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ... ʔawir = you take ...

..

However 37 monosyllabic maŋga are exceptions : they pattern exactly the same as poly-syballic verbs.

..

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to store | ||

| yái = to have | |||

| jò = to go | jwòi = to to pass through, undergo, to bear, to endure, to stand | ||

| féu = to exit | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

| bái = to rise | byó = to own | blèu = to hold | bwí = to see |

| gàu = to do | glù = to know | gwói = to pass by | |

| día = to arrive / reach | dwài = to pursue | ||

| lài = to become | |||

| cùa = to leave / depart | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slài = to change | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kàu = to fall | kyò = to use | klói = to like | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyá = to fly | plèu = to follow | |

| té = to come | twá = to meet | ||

| wè = to think | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to learn |

..

For example ... pòr nambo = he/she enters the house ... not *poyor nambo

The above are also among the most common verbs as well. If you are serious about learning béu you should try and memorize them as soon as possible.

..

..... Copulas

..

There are two copula's ... sàu "to be" and lài "to become". You will see that they were listed among the 37 special short verbs. However they pattern differently from the other 35 as we shall see.

The three components of a copular clause have a strict order ... "copular subject" => "copula" => "copula complement" ... the same order as English in fact.

The copula subject is always unmarked.

..

However the indicative mood is not derived from the infinitive by the usual method. As you might remember the first 3 slots are mandory in the indicative form (the aortist tense being a null morpheme).

But for sàu and lài things are radically different. Below are the indicative forms for sàu and lài.

..

..

Note that the third column (under lài) are grammatically all R-form's ... even though they don't actually have any rhotic sound.

For sàu in the aortist tense, r is the complete copula. It is a clitic attached the the last vowel of the copula subject (however it is always written as a separate word). For example ....

tomo r tumu = Thomas is stupid

It takes the tone of the copula subject (if the copula subject has one).

If the copula subject ends in a consonant then rò is used. For example ....

géus rò solki = the green one is smoothe

Evidentials can be added as normal to these forms. For example ...

jene gáu rìs hauʔe = "They say old Jane used to be beautiful"

jono jutu lòn gáu = "I guess big John is becoming old" ... note that lón is considered mote appropriate than lán. If the timeframe of the action was a lot shorter then lá would be considered appropriate.

..

It is only the R-forms of the copula's which are irregular. All other forms are perfectly normal.

..

sàu bòi = Be good ................................................................. U-form

kodor sə kludado = He works as a clark ................................ I-form

..

Note that for copular clauses, the subject noun or pronoun can never be dropped, because the person/number information is gone (that is ... there is no component to the left of the "r"). For a normal verb ... if the subject is 1st or 2nd person ... then the pronoun is invariably dropped. For 3rd person, whether you have a proper noun, pronoun or nothing depends upon discourse factors.

wài r wikai tè nù r yubau = "we are weak but they are strong"

ʃì r helkia = "it is broken" [ ʃì hulki ]

..

Often the object of certain transitive verbs can be unceremoniously dropped if it is thought too trivial and/or unknown. For example solbara "I am drinking" is complete in itself [both in English and in béu] even though drink and solbe are transitive verbs. That is ... no need to say "I am drinking something" in English ... no need to say solbara efan in béu.

The copula subject in certain situations can also be dropped. The reason for this is the mirror image to the reason for dropping an object. Whereas the object is thought "too trivial" or "unknown" the copula subject is thought too "all encompassing". (English usually uses a dummy subject, "it" in similar situations)

When béu has no copular subject ... sər [ written as s-r from now on ] is the form of the copula used. ( Notice that this is what the 3sg indicative impersonal form of sàu would be if it were conjugated as a regular verb )

As with English, this construction is often used for the weather ...

fona = rain : fonia = rainy/raining : fonua = dry (well not raining). So ...

s-ra fonia = it's raining

..

Often when discussing the advisability of some course of action a construction containing s-r + one of the adjectives neʒi, boʒi or fàin + gò are used. For example ...

..

| səra | neʒi | gò | ny-e-r-u | jindi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "it is"-PRES | necessary | CMPZ | return-2PL-IND-FUT | now |

==> It is necessary that you (pl) will return to home now ==> You (pl) must go home right now

| bù | səra | fàin | gò | sw-a-r-u | ifan | jindi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEG | "it is"-PRES | appropriate | CMPZ | speak-1SG-IND-FUT | anything | now |

==> It is inappropriate that I will say anything now ==> I shouldn't say anything now

| sər-u | boʒi | gò | jubu | j-u-r-u |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "it is"-FUT | optimum | CMPZ | nobody | go-3PL-IND-FUT |

==> It will be best if nobody goes

..

neʒi = necessary ................. the action is a vital part of some larger scheme (that will achieve some goal) ........... moze r neʒi LIFE.wo = water is necessary for life

boʒi = best ........................... the action will yield more benefits than other actions (or no action at all).

fàin = fitting/appropriate...... the action will be approved of by society at large (or at least the subsection society that is interested in the matter).

Note the two nouns ... neʒis = "a necessity and boʒis = "the optimum"

..

For new situations ... l-r is used instead of s-r. (Notice that l-r is what the 3sg indicative impersonal form lài would be if it were conjugated as a regular verb). For example ...

l-ra fonia = it starting to rain

The form l-r is quite a bit rarer than s-r.

..

OK ... So sàu and lài are the two copula's of béu.

There is another verb, that while not a copula, can function in a way similar to s-r.

While s-r connects an attribute ( adjective ) to the universe at large (well at least attaches an attribute to the local environment) y-r connects a noun to the universe at large. y-r is actually the 3sg indicativeimpersonal form of the verb yái "to have on you".

yái is often used to connect a human subject to a object (stupid English) object. For example ...

jonos yór kli.o = John has a knike

yái can also be used to connect a location subject to any physical object. For example ...

| tunheu-s | y-o-r-e | yiŋki | hè | yildos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "townhall"-ERG | "have"-3SG-IND-PST | "attractive girls" | alot | morning |

==> the townhall had many attractive girls this morning*

This usage can become impersonalized (i.e. the locative subject can be deleted) and the meaning then becomes ... the physical object exists somewhere in the Universe. For example ...

y-r dèus = "there is a God" or "God exists"

This construction can be negated in two ways ...

bù y-r dèus = "there isn't a God" : y-r jù dèus = "there is no God"

..

Going back to the original example ...

y-r yiŋki hè = "There are many attractive girls" ............................................................................... [ they exist somewhere ... somewhere in the Universe ]

The above can be modified ... below we modify it with an "adjective phrase of location" tunheuʔe and an "adjective phrase of time" [Notice the tense of y-r must be adjusted to agree on the last one ]

(1) y-re yiŋki hè tunheuʔe yildos = "there were many attractive girls at the townhall this morning"..... [ this changes the meaning from "Somewhere in the Universe" => "a more Specific Locality" ]

Which actually means exactly the same as (2) tunheus yore yiŋki hè yildos

Which in turn means pretty much the same as the copula sentence (3) yiŋki hè rè tunheuʔe yildos = "many attractive girls were at the townhall this morning" ... so three ways to say the same thing.

But note ...

*tunheuʔe rè yiŋki hè yildos = "at the townhall this morning were many attractive girls"

The above construction that is allowed in English is not allowed in béu ... well you can't say "green is the man" in English

..

..... Another passive

..

We have seen the impersonal passive above (where the vowel before the r becomes a schwa.

However there is another passive form made with the verb jwòi "to undergo" plus the infinitive.

bwari jono katala lazde = I saw John cutting the grass ....................... katala lazde is a saidau kaza ..... katala is a saidau baga

bwari lazde jwola kata = I saw the grass being cut ............................. jwola kata is a saidau kaza

bwari lazde jwola kata hí jono = I saw the grass being cut by John .... jwola kata hí jono is a saidau kaza

Note ... although the là suffix is probably connected to the second pilamo it should be recognized as a separate siffix here. If it was the pilamo we would have ... bwari lazde là jwòi kata

bwari lazde kataya = I saw the grass that has been cut

bwari lazde katawa = I saw grass that must be cut = I saw that the grass must be cut

lazde katawa bwari = I saw the grass that must be cut

bwari lazde nài r katawa

..

..... Six causative constructions

..

"John made Jane drink the water" is an English causative construction ... [Note on terminology ... we call "John" the "causer" and "Jane" the "causee"]

..

In a similar manner to English ... béu uses gàu (meaning "to do" or "to make") as the neutral term for coding causation. For example ...

(a) jonos gore solbe moze jenen = John made Jane drink water (earlier today)

..

| jono- | g-o-r-e | solbe | moze | jene-n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John-ERG | "do"-3SG-IND-PST | drink.INF | water | Jane-DAT |

..

Note that the causee gets the dative affix. Also note that maŋga immediately follows gàu, the maŋga object immediately follows maŋga. The causee can come anywhere but the string gore solbe moze can not be broken. There are 3 possible places where jenen can appear.

And another example ...

jonos gore náu onyo waulon jenen = John made Jane give the bone to a dog (earlier today)

Notice that we have two datives in this construction. The string gore náu onyo waulon can not be broken.

..

This construction implies that the causer was present when the event happened. We call it a "direct" causative construction.

There is another causative construction which doesn't imply the causer was present when the event took place. In fact it implies that the causer took some action which at a later time made the causee do what they did. The two actions very probably being linked by some sort societal connection (via other people).

(b) jonos gore gò jenes solbore moze = John had Jane drink water

The clause after gò ( i.e. jenes solbore moze ) has free word order.

The indirect causative construction is iconic ... separating the two verbs with gò reflects the separation of the two events ... both timewise and otherwise (i.e. there could have been a chain of protagonists involved).

..

There are 4 other causitive constructions in béu ... gàu is neutral as to how the causee views the action they are made to do.

If the causee is reluctant ... we use tumai "to squeeze" or "to press" instead of gáu.

If the causee is eager ... we use náu "to give" instead of gáu. For example ...

..

(c) jonos tumore solbe moze jenen = "John made Jane drink water" or "John forced Jane to drink water (earlier today)"

(d) jonos tumori gò jenes solbore moze = "John had Jane drink water" or "John arranged that Jane had to drink the water" ... (the drinking occurred earlier today, the causing of the drinking ... yesterday or before)

(e) jonos nore solbe moze jenen = "John let Jane drink the water (earlier today)"

(f) jonos nori gò jenes solbore moze = "John allowed Jane to drink water" or "John arranged for Jane to be able to drink water" ... (the drinking occurred earlier today, the arranging of the drinking ... yesterday or before)

..

Notice that in (a), (c) and (e) the maŋga must occur immediately after gàu, tumai or náu. This is the same as the French, Italian or Spanish causative constuctions. Here is a French example ...

..

==> I will make Jean eat the cakesje ferai manger les gâteaux à Jean 1sgA make+fut+1sg eat+inf the cakes prep Jean

..

(a), (c) and (e) have what is called a compound causative verb. (i.e. one clause) ... (b), (d) and (f) are what are called periphrastic causative constructions. (i.e. two clauses)

..

It is possible for the indirect paraphrastic construction to give the embedded clause an impersonal form. For example ...

jonos gori gò solb-re moze = "John had the water drunk" or "John arranged for someone to drink the water" ................. [notice : no causee]

..

..

In the above table, it can be seen that there are 6 causative constructions. There are 3 degrees of "volition" (the willingness of the causee) and 2 degrees of "directness" (did the causer act directly on the causee or through intermidiaries).

..

It is possibly to chain causative constructions together. For example ...

..

jonos flòn jodoi = John feeds the animals.

g-r gò jonos flòn jodoi = John is made to feed the animals.

(nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = they make John feed the animals.

gàu gò (nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = make them make John feed the animals.

by-r gàu gò (nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = it is necessary to make them make John feed the animals.

(gís) byír gàu gò (nús) gùr gò jonos flòn jodoi = you must make them make John feed the animals.

..

And 2 of these 3 causative verbs can be given impersonal forms ....

jenen g-ryə doika or g-ryə doika jenen = "Jane has been made to walk" or "somebody has make Jane walk

jenen tum-ryə doika or tum-ryə doika jenen = "Jane has been forced to walk" or "somebody has forced Jane to walk

Now náu "to give" is a strange word in that it never takes an impersonal form (see the section above). Instead the word mài "to receive/get" is used.

jene moryə doika = "Jane has been allowed to walk" ... [ as opposed to *jenen n-ryə doika ]

We will learn more about mài Ch 4.6 and Ch 4.7.

..

Another verb that we can mention here is penau meaning "to persuade, coax, convince, bring around, influence, sway"

penarua jene jonowo = "I intend to persuade Jane about John" = "I intend to bring Jane around to my way of thinking with respect to John"

(pás) penare jono jò nambon = "I got John to go home" = "I persuaded John to go home" .... [Note ... the maŋga does not immediately follow for penau ]

(pás) penare jono gò baba yor jò nambon = "I persuaded John that father should go home"

Also penau says nothing about the success of the action ... unlike the 3 other verbs we have considered where success is assumed.

..

..... Two quotative verbs

..

béu has two quotative verbs ... swé and aika. What I mean by the term "quotative verb"is a verb which must* be accompanied by a string of direct speach ["sods" from now on]

swé = "say" and aika = ask .... ( that is to ask for information, to request something (to ask for) has a completely different root ... namely tama )

I guess it is intransitive because the speaker never takes the ergative ending "s". The spoken to (if mentioned) takes the dative ending "n".

[Some people would like to argue as to whether "sods" = an object or whether "sods" = a complement clause. I think this is not worth arguing about. It is similar to arguing about how many angels can stand on the end of a needle. ]

There is an ordering restrictions for a clause formed around a quotative verb ... the "sods" must appear adjacent to swé or aika. It doesn't matter which comes first but they must be adjacent ... normally both elements are pronounced in the same intonation contour. A second restriction is that there must be a pause at the other end of the "sods" ... the opposite end from the quotative verb. For example ...

John said "Ai ... go away" => jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo where aiʔdo is an interjection expressing frustration and ojo is quite a rough way to say "go away".

This can also be expressed as aiʔdo ... ojo swori jono or jono ... aiʔdo ... ojo swori or even swori aiʔdo ... ojo ... jono. The first two patterns are the most common followed by the third pattern and the fourth a distant last. Notice that the "sods" that I chose for demonstration purposes entails an internal pause.

If we introduced a dative element ...

John said to Jane "Ai ... go away" => jono jenen swori aiʔdo ... ojo

The above would be the most common ordering of constituents ... but again quite a bit of freedom with respect to word ordering.

The "sods" can be quite lengthy ... 2 or 3 or 4 clauses and follows as near as possible the speach pattern of the original speaker.

The béu orthography is a bit quirky when it comes to quotative verbs. In CH 1.8 we briefly mentioned the deupa. These are actually used to bracket any "sods". Also it is common to drop the actual quotative verb. (well after the time setting of the speach act(s) are revealed anyway). For example ...

The first one is graphically jono [ aiʔdo ... ojo ] ... (for an explanation of the graffic form of the interjection aiʔdo, look back to CH 1.2)

The second one is graphically jono [ bàu nái ]

These would be read as jono swori aiʔdo ... ojo and jono aikori bàu nái (John asked "which man")

But how do we know that swé should be associated with one and aika to the other ? Simple ... if you have a question word within the deupa then you know you should pronounce aika ... if not you pronounce swé. We have encountered these question words already in CH 2.10. There are ten of them but the first two have two forms. Here they are again ...

..

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| láu | "how much/many" |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| dá | where |

| kyú | when |

| sái | why |

| nái | which |

| ʔai? | "solicits a yes/no response" |

| ʔala | which of two |

..

The only time that you hear these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are in the same intonation contour as the verb "aika" in one of its forms.

The only time that you see these ten words and you are NOT being asked a question is when these words are sandwiched between two deumai.

This is quite a bit different from English where question words have been appropriated to function as relativizers, complementizers and what have you (heads of free relative clauses).

In the above ... when pronouncing words ... swé or aika is inserted where the first bracket appears. It could equally well be that swé or aika is inserted where the second bracket appears. It is deemed to not really matter that much. However in carefull writting the proper position of the quotative verb can be indicated. For example ...

In the above a pause (gap) is visible just above the top deupa. From that it is logical to deduce that swé or aika should be inserted after the "sods". (from the word order and intonation rules given earlier). But most of the time ... when reading out loud ... people do not take much heed to whether the quotative verb is placed over the deupa damau or the deupa dagoi.

In a textblock, which you have a lot of dialogue it is common to colour code the "sods" with respect to the speaker. For example ...

When this happens the deupa has no gold filling. It could be possible to drop the speakers name also once the colour coding scheme is established. This really depends upon how much dialogue is involved. Maybe each speaker would be mentioned again at the start of every textblock ... just to keep the protagonist <=> colour mapping alive in the readers mind.

..

* In the very first sentence of this section I said that "quotative verb"is a verb which must be accompanied by a "sods" ... not quite true. The determiners dí and dè can take the place of a "sods". In these constructions dí refers to a "sods" that will be revealed imminently ... dè refers to a "sods" that was spoken in the past.

If Jane pronounces an opinion about something ... if John had pronounced roughly similar in the past ... it would be fitting to say jono swori dè.

If you are about to replay some utterance by John on a voice file, it would be appropriate to say jono swori dí just before playing the voice file.

..

IMPORTANT ... The only time you hear direct speech is when swé or aika is present in one of its forms.

..

..... Speech verbs

..

We have already briefly touched on serial verb chains. These are in fact the i-form of the verb.

The i-form of swé is often used to give strings of direct speech in conjuction with another verb. Usually this other verb denoted some time of speech event. There are around 50 speech-verbs in béu ... melita "to agree" : noluja "to disagree" : malapa "to equivocate" : : oldo "to order/command" : endo "to introduce/recommend" : enji "to suggest" : ʔuaho "to exclaim" : ʔaume "to scream" : uhozo "to exhort/urge" : dauŋgo "to repeat/relay" : diŋkli "to discuss" : dawata "to haver" : daumpa : "to scold/berate" ... etc. etc.

..

uhozo is an S-verb meaning "to urge", "to exhort".

So you could use uhozo as the main verb in the clause and then can add the sods marked with swə ...

uhozora jenes jono ... gì r boimos swə => Jane is cheering on John shouting "you are the best"

..

| uhoz-o-r-a | jene-s | jono | gì | r | boimos | swə |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "exhort"-3SG-IND-PRS | Jane-ERG | John | you | COP | the best | saying |

..

dauŋgo is an S-verb meaning "to repeat, to relay"

tomos dauŋgore jene swə gì r boimos = Thomas repeated Jane saying "you are the best"

..

The i-form of aika is also used fo give "sods". For example ...

daulau is an NS-verb meaning "to joke".

daulori jene jonotu aiki bla bla bla => Jane joked with John asking bla bla bla (well to make this a good example I would have to invent a quite involved scenario, but I hope you get the idea ... even with the ellipses)

..

The use of alki and swə in conjunction with one of the speech act verbs are an important structure in béu grammar and adds to the beauty and functionality of the language.

This structure is really only applicable to speech act verbs. If it was used with a non-speech-act verb it would sound a bit strange to the ear of a béu speaker. For example ...

?jono doikori dunheun swə falaja r NICE sowe = John walked to the civic centre saying "what a beautiful morning"

..

béu maintains a dichotomy between speech-verbs and thought-verbs. Speech-verbs can take a swə/aiki adjunct whereas thought-verbs can take a complement clause introduced by the particle gò in place of an O argument. We will go into this more in the next section.

This dichotomy is not total though. There is some merging between the two constructions.

For example ... ʕelo "to hear" may be considered unique w.r.t. the constructions it can appear in ...

ʕelari jwadoi = I heard some big birds

ʕelari jono = I heard John

ʕelari jono swé bù ʔár jò = I heard John say "I don't want to go" ....... OK I suppose we analyze swé bù ʔár jò as an adjuct similar to swə bù ʔár jò in jono nolujori swə bù ʔár jò "John disagreed saying "I don't want to go"

ʕelari gò jono bù jorua I heard that the jono doesn't intend to go

ʕelari swər bù jarua = I heard it said "I will not go" .............. And we can analyze this as an transitive verb where the object has been dropped.

Also glùn "to inform, to tell" is both a thought-verb and a speech-verb. The informer is in the ergative, the informed the dative. The object can be an object (i.e. the news) or a complement clause (i.e. gò jono bù jorua) or it can simply be missing (when we use glùn as a speech-verb) ... or should we consider that when it is used as a speech-verb that there is an object ... something generic like "the news" but that it can be dropped. Well neither answer is right in itself.

..

..... Thought verbs

..

Everybody carries an (imperfect) model of his environment in his mind and uses this model to plan his actions. The main reason HUMANS have been so successful compared to other animals is that we have a more complete model than ... say ... our primate cousins. The reason that out model is good is that we have LANGUAGE and so get information from our fellows. Probably the building of this MODEL and LANGUAGE were co-developements and could well be reflected in the size of the HUMAN BRAIN over the last few million years. I believe that this MODEL and LANGUAGE are intertwined and hence I don't think it is a good idea to consider either in isolation.

Now usually when we communicate ... we just talk about reality. For example ... JOHN IS TALL. We do not acknowledge the actual more complicated situation ... IN MY WORLD MODEL, JOHN IS TALL.

But sometimes we do .... usually when we are talking about activities related to our mind ... like "thinking", "knowing" ... disseminating knowledge to our fellows "telling", "saying" ... gathering knowledge first hand "seeing", "hearing" ... trying to gather knowlege from our fellows "asking". All these bracketed verbs can take what are called complement clauses. When you see a complement clause you are seeing an admission that what we are talking about is not in fact REALITY, but some MODEL of REALITY. Maybe you could say that it is an admission that we are using META-DATA rather than DATA.

The 4 panels below might illuminate what I am trying to say. What is on the white background is REALITY. What is on a black background is part of a MIND MODEL . The script on an orange background is a speach act appropriate for the situation shown. The top panel is the way that we normally speak ... that is REALITY is presented directly with no referrence to any MIND MODEL.

Now it seems that the majority of languages have at least one way of bracketing off the META-DATA from DATA. English has two types of complement clause (CC from now on) ... one introduced by the complementizer "that" and the other introduced by a question word. These usually take the place usually taken by an O argument. béu has one CC which is introduced by the particle gò. Some of the thought-verbs that can take either a CC or an O argument are listed below ...

petika "to select/choose/pick/decide" : glù "to know" : wè "to be thinking about/consider/ponder" : celba "to remember" : dolka "to forget" : wespila "to understand" : glùn "to inform/tell" : celban "to remind" ... etc. etc.

béu does not have indirect speech as English has ... i.e. John said (that) that was stupid. In béu this would have to be framed as direct speech ... i.e. "this is stupid" said John (notice the change of reference for time and argument). Also ... "John asked whether I wanted to go" would be recast as "John asked "you want to go ?" "

The béu CC is exclusively used for thought-verbs ( IS THERE AN EXCEPTION TO THIS ?? )

..

..... The reciprocal construction

..

The reciprocal particle is bèn

jonos jenes timpur bèn = "John and Jane are hitting each other" = "John and Jane hit one and other"

Note ... lè "and" is not used when two nouns in the ergative case occur adjacent to each other.

The particle also comes after adjectives occasionally. For example ...

jono lè jene r ʔài bèn = John and Jane are the same.

No real reason why it should be added to the above sentence ... except that it is judged to sound good.

ʔáu bèn "to take mutually" is the béu expression meaning ... do the dirty deed, have relations, roger, root, shag, boink, slam the clam, thump thighs, pass the gravy, wet the willy, make the beast with two backs ... make love.

..

..... Five slots before the verb

..

We have already covered the 5 slots for "agent", "tense/aspect", " r, "evidentiality", "perfect" at the end of the denuded infinitive. As well as the nuances given by these suffixes, there are particles which add further information to the basic verb. These are called (near-standers ?). These particles occur in 5 pre-verbal slots and a maximum of one is allowed from each slot.

The complete verbal block is shown below ...

Some restrictions on the co-occurence of these termsare given above. There are some additional restrictions not given above. For example juku is how you negate the perfect (dropping the yə). As yə can not co-occur with ʔès/ʔàn or jù, juku also can not co-occur with ʔès/ʔàn or jù.

..

... Slot 1

..

These two particles indicate probability.

màs = possibly

lói = probably

The probability distribution for màs centres around 50 %.

The probability distribution for lói centres around 85 %.

..

... Slot 2

..

bù is a negative particle which has scope over the entire sentence ... equivalent to "not" in English.

..

awa gives a "habitual but irregular" (maybe best translated as "now and again" or "occasionally" or even "not usually") meaning to the verbal block. Possibly related to the verb awata which means "to wander".

..

bolbo gives a "habitual and regular" (best translated as "normally" or "usually" or "regularly") meaning to the verbal block. Possibly related to the verb bolboi which means "to roll".

..

juku is used for negating the perfect aspect. To negate the perfect aspect you insert juku in this slot and delete the yə. juku means "never" which is the opposite of one of the perfect meanings. Namely "at least once"

By the way ... this negative construction mirrors what is done in Mandarin ... 没 méi or 没有 méiyǒu is used instead of 不 bù and the aspect marker 了 le is omitted.

..

Some examples of usuage ...

..

| kodoriyə | he had worked | juku kodori | he had never worked |

| kodoreyə | he has worked (earlier today) | juku kodoreyə | he hasn't worked (so far) today |

| kodoryə | he has worked | juku kodora | he has never worked |

| kodoruyə | he will have worked | juku kodoru | he will never have worked |

..

The usuage of -yə is given in section 1.2.5 earlier in this chapter. A good idea to revise it now.

..

Note ... In English you can say ... "horses never fly" which would be *juku pyár fanfai in béu. However the generic/habitual tense is not allowed with the perfect in béu so ... "horses never fly" => bù pyár fanfai. And why is generic/habitual tense is not allowed with the perfect ... well there is an addage in English "never say never". This addage is true ... or at least "never say ever" is ... which is the same thing :-)

..

... Slot 3

..

These are called aspectual operators or aspectual particles. (I like the term "overlap words" myself)

..

... Overlap words

..

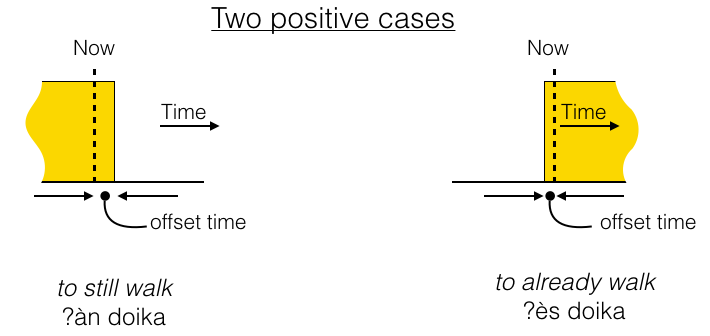

In English the nearest translations* are ʔàn = "still" and ʔès = "already".

Many many languages have equivalents to these two particles. For example ...

..

| English | still | already |

| German | noch | schon |

| béu | ʔàn | ʔès |

| French | encore | déjà |

| Mandarin | hái | yîjing |

| Dutch | nog | al |

| Russian | eščë | uže |

| Serbo-Croatian | još | već |

| Finnish | vielä | jo |

| Swedish | än(nu) | redan |

| Indonesian | masih | sudah |

..

ʔàn indicates ...

1) An activity is ongoing.

2) The activity must stop some time in the future, possibly quite soon.

3) There is a certain expectation* that the activity should have stopped by now.

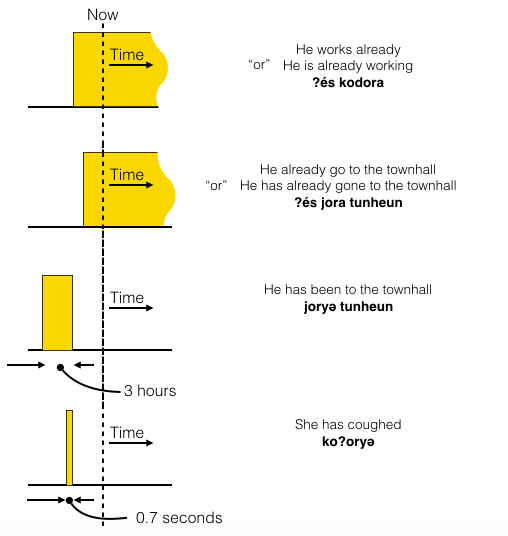

ʔès indicates ...

1) An activity is ongoing.

2) The activity was not ongoing some time in the past, possibly quite recently.

3) There is a certain expectation* that the activity should not have started yet.

..

* Inevitably a connotation of "contrary to expectation" will develope to a certain degree. This is because if the situation was according to expectation often nothing would need be utterred. Hence ʔàn and ʔès are often found in contrary to expectation situation which in turn colours their meaning.

..

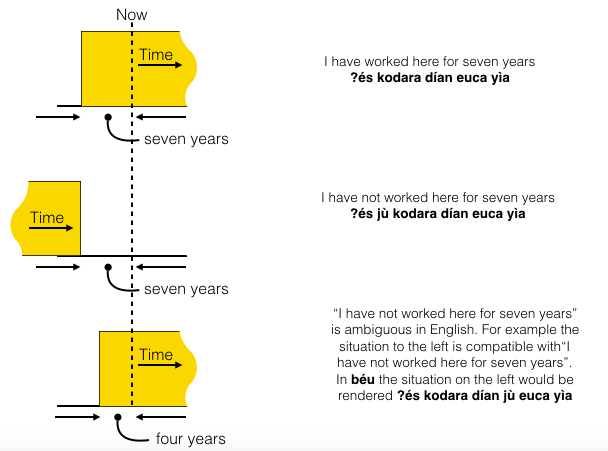

..

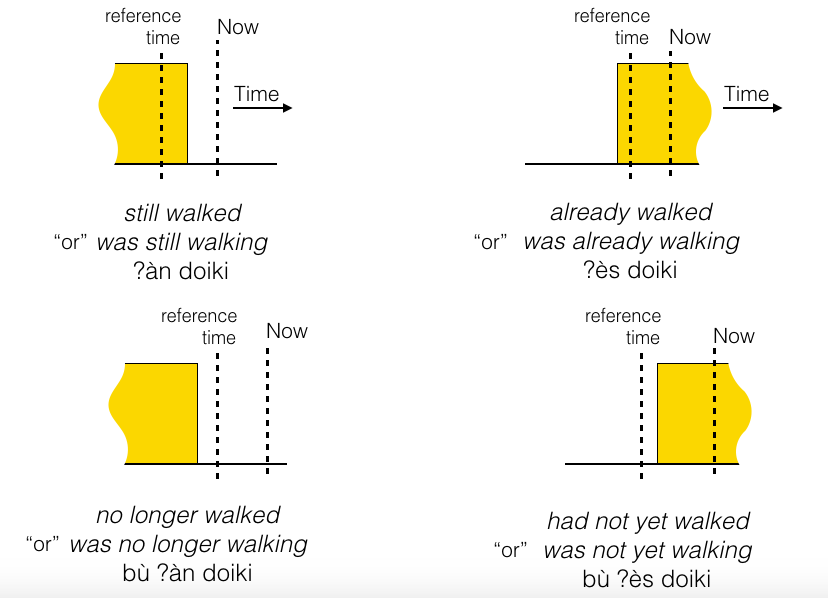

A very interesting thing about the above two situations is how they are negated. Either the verb can be negated or the operator can be negated. (The verb is always under the scope of the operator so if you negate the operator you are also negating the verb). The first case I represent with a bar over the verb. The second I represent with a bar over the operator+verb.

On the diagram ... If the verb is negated ... then the yellow place becomes white and the white space becomes yellow.

On the diagram ... If the operator+verb is negated ... the dashed line representing "now" changes places with the line that represents onset/cessation of activity.

..

..

As you see by above ... by changing whether the negator act on the operator+verb or whether only on the verb give diametrically opposite meanings.

Note that there are 4 possible negative cases to choose from and a language only needs 2. A language (to cover all negative cases) should be either "(a) (b) type" or "(c) (d) type" or " (a) (c) type" or "(b) (d) type"

Cross linguistically there are interesting variations. All Slavic languages prefer verb negation, hence they are (c) (d) types.

In German, only (a) and (c) are allowed in positive declarations.

Nahuatl has negation of the operator so is (a) (b) type.

It can be said that English also is basically (a) (b) type. However English has suppletion ... "yet" for "already" : "anymore" or "longer" for "still" ... hence "not yet" and "no longer" (I guess this lessens the chance of mishearing).

In béu, bù negates the whole clause so you can say that béu is basically (a) (b) type.

..

For ʔès ...

| ʔès | kod-a-r-a | dían |

|---|---|---|

| already | work-1SG-IND-PRES | here |

==> I already work here

| bù | ʔès | kod-a-r-a | dían |

|---|---|---|---|

| not | already | work-1SG-IND-PRES | here |

==> I don't work here yet

And for ʔàn

| ʔàn | kod-a-r-a | dían |

|---|---|---|

| still | work-1SG-IND-PRES | here |

==> I am still working here

| bù | ʔàn | kod-a-r-a | dían |

|---|---|---|---|

| not | still | work-1SG-IND-PRES | here |

==> I no longer work here

..