Béu : Discarded Stuff: Difference between revisions

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== ..... Functions of làu== | |||

I DECIDED LAÙ SHOULD NOT PRECIDE NOUNS ... | |||

[actually '''jono r làu bòi jenewo''' can also be expressed as '''jono r làu jene boiwo''' ... the two forms mean exactly the same ('''boiwo''' = '''boimiwo''' [with respect to goodness] but -'''mi'''- is inevitably dropped when -'''wo''' is adjoined) ] | |||

And another example ... | |||

'''jono r làu bòi jenewo kludauwo''' = "john is as good at writing as jane" | |||

which can also be expressed as '''jono r làu bòi kludauwo jenewo''' OR '''jono r làu jene boiwo kludauwo''' and '''jono r làu jene kludauwo boiwo''' ... however '''kludau''' can never immediately follow '''làu''' | |||

.. | |||

== ..... Thinking about sets and subsets== | == ..... Thinking about sets and subsets== | ||

Revision as of 00:54, 6 September 2016

..... Functions of làu

I DECIDED LAÙ SHOULD NOT PRECIDE NOUNS ...

[actually jono r làu bòi jenewo can also be expressed as jono r làu jene boiwo ... the two forms mean exactly the same (boiwo = boimiwo [with respect to goodness] but -mi- is inevitably dropped when -wo is adjoined) ]

And another example ...

jono r làu bòi jenewo kludauwo = "john is as good at writing as jane"

which can also be expressed as jono r làu bòi kludauwo jenewo OR jono r làu jene boiwo kludauwo and jono r làu jene kludauwo boiwo ... however kludau can never immediately follow làu

..

..... Thinking about sets and subsets

| 1 | moltai dí | this doctor | ||

| 2 | ú moltai dí | the whole doctor here | ||

| 3 | ú moltai.a dí | all the doctors here | uku fì moltai.a dí * | "all of the doctors here" or "every one of the doctors here" |

| 4 | moltai moltai dí | every doctor here | ||

| 5 | hài moltai dí | many doctors here | hàis fì moltai.a dí | many of these doctors |

| 6 | iyo moltai dí | a few doctors here | iyos fì moltai.a dí | few of these doctors |

| 7 | euca moltai dí | seven doctors here | eucas fì moltai.a dí | seven of these doctors |

| 8 | hói moltai dí | two doctors here | hóis fì moltai.a dí | two of these doctors |

| 9 | ʔà moltai dí | one doctor here | ebu fì moltai.a dí | one of these doctors |

| 10 | jù moltai dí | no doctor here | jubu fì moltai.a dí | none of these doctors |

| 11 | ín moltai dí | any doctor here | ibu fì moltai.a dí | any of these doctors |

| 12 | èn moltai dí ** | some doctor here | ebu fì moltai.a dí | one of these doctors |

| 13 | èn moltai.a dí | some doctors here | embu fì moltai.a dí | some of these doctors |

..

You may ask what is the difference between the first column (row 1-13) and the second column (row 5-13). The answer is ... the second column imparts an "partitive" meaning. For example ... euca moltai dí just means, we are talking about "seven doctors and they are here". But eucas fì moltai.a dí means, we are talking about "seven out of a (significantly) larger number of doctors here"

Notice row 9 and 12 of the second column have the same form in béu

If you cast your mind back to what we discussed in the last section. Well to use one of the construction in the second column is to "zoom in". It is to narrow the scope of the items we are focusing on.

* Actually uku fì moltai.a dí is a bit infelicitous. You hardly ever here it. Better to say ú moltai.a dí ... more snappy !

* Actually èn moltai dí (row 12, column 1) ... is a bit infelicitous. You hardly ever here it. Better to say ʔà moltai dí.

There are 5 pronouns that can be considered to be plural ... wìa yùa jè nù and ʃì [ consider these with different cases ?? ]

| 3 | ú nù | all of us |

| 4 | nù nù | every one of us |

| 5 | hài nù | many of us |

| 6 | iyo nù | a few of us |

| 7 | euca nù | seven of us |

| 8 | hói nù | two of us |

| 9 | ʔà nù | one of us |

| 10 | jù nù | none of us |

| 11 | ín nù | any of us |

| 12 | èn nú | some of us |

| 13 | èn nú |

..... Printing .... I will probably need some of this later

..

I will probably need some of this later ... when I figure out how (direct) speech works

Punctuation and Page Layout

..

The letters in a word are always contiguous, that is there is always a line running right through the word. Writing is firstly from top to bottom and secondly from left to right.

Between words there is a small break in the line. The break should be 25% the height of a letter.

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, this small break would be indicated by dù

Between some words there is a gap. This represents a pause. A pauses in English is represented by a comma, a colon or a semicolon. Whenever an orator draws breath, this will be reflected in the writing by a gap. Also there are occasions where the grammar of béu demands a gap. A gaps hould be 75% the height of a letter. When such a gap is required I will represent in in my transcription as an underscore. (I could have used a comma, however I prefer not too ... presumable in English, commas originally were always used for pauses in speech. However nowadays in English many pauses are not represented in any way (presumably in these cases when it is not necessary for reading comprehension. Also in English, in a surprising amount of text commas are found where they shouldn't be. In béu gaps in a textblock have a one-to-one correspondence to a pause in speech).

*When listing items, béu is similar to English ... there is pause between every item except the last two items. Between these items, béu has lé, English has "and".

..

suna_dunu_celai lé àu = "orange, brown, pink and black" ... notice the two gaps and then the two breaks in the béu script above.

By the way, this would be spelled out as ... ‘’’sadu sanu nùa sana jù_duzu sanu nùa sanu jù_compa sane lata sanai dù_lata dite dù_sanau dù dù’’’

..

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, the gap is indicated by saying jù

Single gaps are very common. Occasionally you can have "double gaps" and even "treble gaps". These rare creatures represent "pregnant pauses" which are sometimes used for comic effect.

When telling somebody how to spell a succession of words, a "double gap" is rendered by bauva ??? , a treble gap by baiba ???.

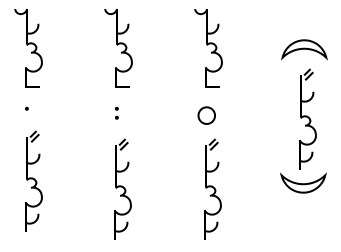

Note the single point used in the "double gap" and the pair of points used in the "treble gap".

For a "double gap" there should be 75% letter height space above and below the dot. For a "treble gap" it is the same plus a 25% letter height space between the two dots. ..

..

There is also a punctuation mark called the "sunmark" ( kòi = sun ). This is basically a full-stop. The "sunmark" has double the diameter of omba (omba means "circle" and is used as a decimal point).

..

There are also punctuation marks called "moonmark" ( dèu = moon ). These are basically brackets. The opening one is called "moonmark" damau and the closing one is called "moonmark" dagoi. Direct speech is enclosed in "moonmarks". These bits of direct speech are also highlighted. Usually the first speaker's words are highlighted in blue and the second speaker's words are highlighted in yellow. The highlighted area is lozenge shape. Every "textblock" the protagonists are reset ??. In a story, after the scene is set ... that is the time of speaking and the identity of the speakers have been established, then their names are dropped from the text and the kloi "speak" is also dropped. However somebody reading the text out loud would give this information from their understanding of the situation.

..

..

In a normal narrative, everything is written in "textblocks".

..

(Please note ... the light lines surrounding the "textblocks" are not real. They are just there to assist me drawing)

..

This is the first page in a "chapter". Notice the symbol at the top left hand side of the first "textblock". This is called a "heavy tile".

Textblocks fit in between "rails" about 4 inches apart. The width of a block should be between 60% and 90% * of the block height. Of course it is best to start a new block when the scene of the narrative changes or there is some discontinuity of the action, but this is not always possible. Then you just must arbitrarily split the text into two blocks. The standard practice is to stretch the text a bit so that the tops and bottoms of every column line up with their neighbours. XXXXXX

There is no way to split a word between two lines (as we can do in the West by using two hyphens). A "sunmark" must be next to the last word in a sentence (it can not go to the start of a new column by itself) However if a "sunmark" fall next to the bottom rail, then the next column will begin with a "sunmark". This is purely due to a love of symmetry.

The first text block starts at the top left (as you would expect). The second textblock starts below where the first text block stops. In fact the vertical space between the stop and the start of the two textblocks is equal to the horizontal "interblockspace" (see the figure above).

If the last "sunmark" of a "textblock" falls next to the bottom rail (as indeed happens with the very first "textblock" of the "chapter", then this "sunmark" is changed into a symbol called a "bottom tile". If a "textblock" ends in a "bottom tile", then what is called a "top tile" will appear before the first word of the next "textblock". This is purely due to a love of symmetry. Note that the "top tile" is exactly the same as the "bottom tile". (Actually in modern printing techniques, the text in complete "textblocks" can be stretched to prevent the final "sunmark" falling on the bottom rail)

When you come to the end of the page (you will have some sort of margin of course and not go all the way to the edge), you simply continue the block on the LHS of the next rail (or page). Below is the second page of the chapter. This page continues on from the page above.

..

In every textblock, one word or short noun phrase is highlighted in red. The shape of the highlighted area is rectangular with rounded edges. Usually a noun is chosen and the more iconic the better. Statistically these highlighted words tend to come towards the beginning of the "textblock".

..

There are two sizes for books. For all hardback books the size is about 8 inches by about 11 inches. For all paperback books the size is about 5 inches by about 8 inches. They are stored as shown in the figure below.

..

..

Unlike books produced in the West, these books are held with the spine horizontal when being read. The hardback page has two "rails" per page (i.e. three dark lines).

On the paperback book, the title is written on the spine and on the front of the book. On the hardback book the title is written on the front, also there is a flap that slides into the spine. However when the book is stored on a shelf, it is pulled out and hangs down. Hence the hardback books can be easily located, even when they are in the bookshelf.

A book will be divided into chapters. A chapter will have a number and usually a title as well. Either at the end of the book or just after the chapter, there will be a page, in which all the highlighted words for a chapter are listed in order. Instead of referencing things by page number, things are reference by chapter and textblock (indictated by the highlighted word(s) ).

Any particular word in a book can be reference by 5 parameters ...

1) "title of book"

2) number of the chapter

3) the highlighted word(s)

4) the number of the sunmarks counted. Actually they are counted backwards ... from the final "sunmark" of the "textblock". Note ... all "sunmarks" are counted, even the ones next to the top rail.

5) the number of the word. This is also counted backwards (i.e. the final word of the sentence is word "1" ... and so on)

* Occasionally very narrow blocks can not be avoided. And of course in mathematical/scientific tracts the tracts are all over the place ... interspersed with diagrams and what have you.

..

..... The Side Verb

..

Let me introduce three dependent clause types here ... the "when" clause, the reason clause and the purpose clause.

1) ... the "when" clause is intoduced by the particle kyù (it is also a generic noun meaning "occasion"/"time" by the way). For example ...

kyù twaru jene ʃì òn fyaru = When I see Jane I will tell her.

Usually the English conditional particle "if"* is also translated as kyù

So ... "if I see Jane I will tell her" => kyù twaru jene ʃì òn fyaru also.

Now let's give the example sentence a habitual meaning ... say Jane fervantly supports Manchester United and the speaker always hears the latest results before Jane. So we have ...

*kyù twár jene ʃì òn fyaru = When I see Jane I will tell her.

Only that the main verb form is not allowed in these three dependend clauses ... if the verb has a final r it must be changed to a final s.

So the proper way to say "when I see Jane I will tell her" => kyù twás jene ʃì òn fyaru

[Now the question is "why substitute final r in a dependent clause, with s ... and it is a difficult question to answer. Maybe it is in recognition that in many natural languages, the verbs in dependent clause have a reduced number of possible forms (refer to what Sonja Cristofaro has written in chapters 125 -> 128 in WALS). Also I find utterance final s more pleasing than utterance r ]

*Other languages to conflate ? "when" and "if" are German (wenn) and Dutch (als). Actually if you really needed to disambiguate in béu you could use jindu meaning "as soon as" or fesʔa meaning "case"(as you can disambiguate in German, by using "sobald" and "falls")

* In English, there is another function for "if" ... it introduces a complement clause when the main clause verb is an "asking" verb. "whether" can also fulfill this function. The particle in béu that fulfills this function is wai.a. wai.a has only this function.

2) ... the reason clause is intoduced by the particle tà. (tà = "because")

XXXXXXX

3) As part of stand alone clauses ...

doikas = "should I walk" or "let me walk" or "how about me walking" or "can I walk" or "maybe I should walk"

doikis = "maybe you should walk" or "why don't you walk" or "how about you walking"

doikos = "let him walk"

doikos jono = "let John walk"

For transitive verbs ...

timpos baus waulo = let the man hit the dog

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding bù (or should that be jù). For example ...

bù doikos = best not to let him walk

They locked him up so that he would starve to death

They let him out at night so that he would not starve to death

..

..... Part of old modality system

slight obligation => might ???

obligation/duty => inevitability

physical ability => sometimes

..

anzu = duty

seŋgo = obligation

alfa = ability

hempo = permission or leave

hento = knowledge

..... Bicycles et al

..

Perhaps can be thought of derived from an expression something like "wagon two-wheels-having" or "wagon double-wheel-having" with a lot of erosion.

Notice that the "item" that is numbered (i.e. wheel) is completely dropped ... probably not something that would evolve naturally.

There are not many words in this category.

jodoʒia* = spider

jodolia = insect

jodogia = quadraped

jodovia = biped

nodebia = a three-way intersection ... usually referring to road intersections.

nodegia = a four-way intersection

nodedia = a five-way intersection

nodelia = a six-way intersection ... and you can continue up of course.

*jodo = animal ... from jode = to move

..

..... Symbols

..

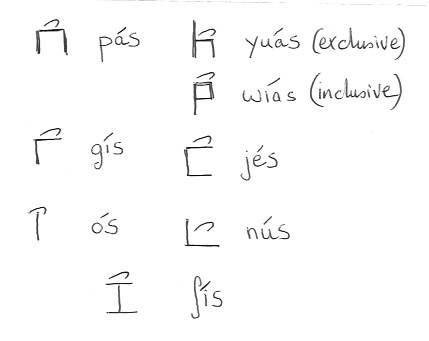

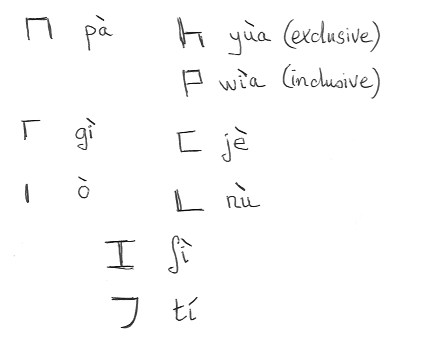

Words are not always written out in full. Certain common words have their own special symbol. For instance the ergative pronouns ...

And the non-ergative pronouns ...

The words "table" = pazba, "bracket" = gizgi, "interior wall" = ozdo and "chair" = yuzlu have probably got some relationship with the above symbols.

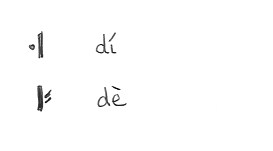

And the determiners ...

Note that dè looks similar to the sign for dùa ... similar but not exactly the same. The two slanting strokes meet the vertical stroke exactly halfway along for dè.

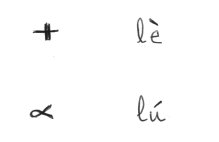

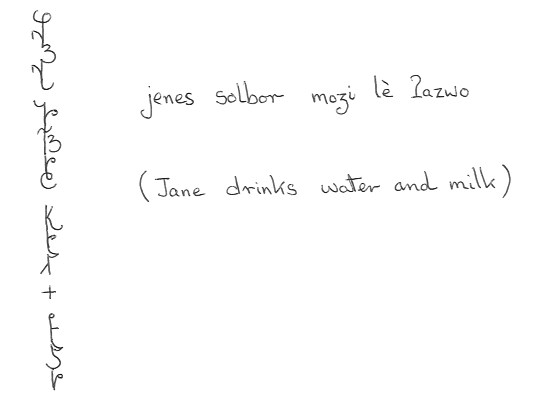

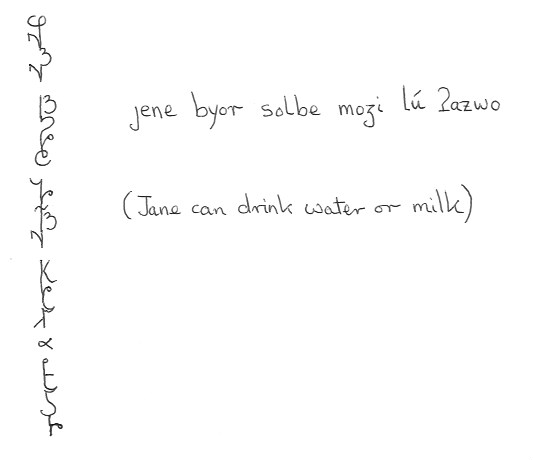

And the particles lè "and" and lú "or" ...

..

..... From the introduction

A brief history

..

The very first language that I tried to construct was called HARWENG. This was eventually given up about 14 years ago. The basic problem was that I didn't know enough about linguistics. I layed down the basic linguistic rules of HARWENG, but when I tried to build upon these basics, what I build did not seem to stick together : it did not make a consistent whole, so reluctantly I put HARWENG aside.

My second project was called SEUNA and this was also put aside after a number of years (I guess for similar reasons to why HARWENG was put aside).

béu* is my third language and I have hopes of taking this one to fruition.

*the diacritic above the "e" indicates that the word has a high tone. All words in this language I will indicate by bold type. From now on the only items in bold type will be elements and words from the language of béu.

..

Motivation

..

What interests me most in linguistics is the area where logic, grammar and semantics intersect. Also I very much appreciate the elegant patterns that are found in natural languages. I guess every natural language exhibits elegant patterns over part of their structure.

However most natural languages also have elements which I don't like. It seems that the natural tendencies that forge a language also "limit" a language in a fundamental way : I find all natural languages insufficiently "efficient" and "elegant" for my taste : evolution by "decree" rather than natural forces just seems so much better.

I have always been a perfectionist ... keenly aware of all the imperfections that everyday life entails. I have always had the feeling that in order to build perfection you must start at the very bottom ... and I also have had the feeling that language is the most basic thing* that makes us human. Hence the first step to making a better world is to develop a logical, elegant and beautiful language.

All of the above motivated me to construct a new language.

..

Influences

..

The best constructed language which I have so far come across was CEQLI. However it was not much more than a sketch. Also the two languages created by Dirk Elzinga ... TEPA and SHEMSPREG were also very neat. However again they were not fully thought out ... not complete languages. I intend that béu will be a fully formed language.

I have not mentioned any of Tolkien's languages as an influence. This is because Tolkien never published a canonical version of ANY of his many constructed languages. However I feel a great affinity for J.R.R. ... I think our world views are remarkable similar ... well at least when it comes to our "secret vice"

..

Structure

..

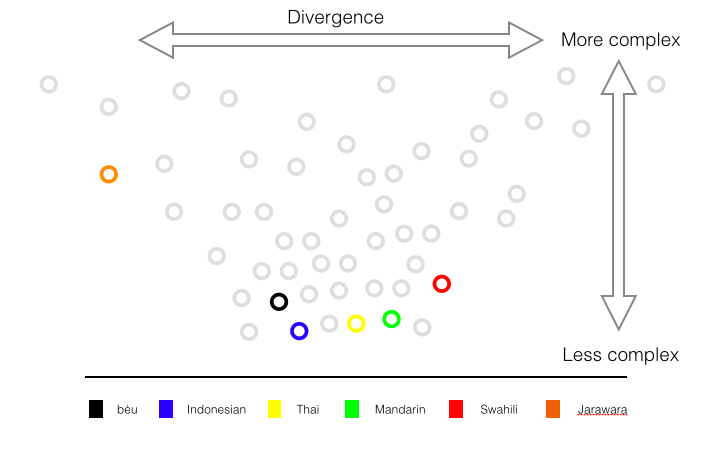

The "bubble fountain" above is how I see the world 4,000 languages (OK I haven't drawn 4,000 bubbles ... pretend) of the world. The vertical axis is complexity. The black line at the bottom represents zero ... the way that a group of people would communicate initially if they all spoke totally different languages and were forced to associate together by some twist of fate. There would be zero grammaticisation ... it would be a very inefficient means of communication and I would presume quite frustrating to try and converse in. The horizontal axis represents how far the different languages diverge from each other (this "divergence" should be multi-dimensional because of course languages diverge from each other in many many different ways ... but I am afraid we must make do with one dimension on my little chart).

You will notice that the simple languages at the bottom of the chart differ less from each other less than the more complex languages at the top. These simple languages tend to have one concept to one word ... they are analytic. Now a simple language is just as fit-for-purpose as a complicated language. And I certainly didn't want complexity for complexity's sake : I just wanted a language that was easy to learn and that would appear to be "natural". Hence the structure of béu is not a million miles away from the structure of English ... or Mandarin. In its final form béu seems like a natural language : the grammar and the "patterns" in the language wouldn't be considered out of place in a natural language.

..

Evolution

..

In its long history (HARWENG => SEUNA => béu) it has changed many many times. It has gone thru' many iterations**. I would change one part of the grammar and then find that this change didn't fit with something else. So I would change it back, or modify the "something else", or maybe try out a completely new paradigm. This happened many many times. I suppose the changes that happened in in the development of béu are similar to the diachronic changes that happen to natural languages, and hence béu ended up looking quite naturalistic.

* I believe that language co-evolved with the increase in the human cranial capacity ... so language has been with us for well over a million years.

** A good analogy to this how a protein takes its shape. This is a long linear chain molecule that folds up on itself to takes on a very definite and complicated shape. The final shape is determined by a series of movements that are initiated by the attractive and repulsive forces that the various links in the chain have for each other. In a similar way the final shape of béu was determined by the way that different grammatical patterns and phonological patterns either clashed with each other, or matched with each other through a number of successive iteration.

..... The Subjunctive

..

The subjunctive verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "s".

The subjunctive is called the sudəpe

The main thing about the subjunctive is that it is not "asserted" ... it is not insisted upon ... there is a shadow of doubt as to whether the action will actually take place.

This is in contrast to the indicative mood. In the indicative mood things definitely happen.

There are three places where the subjunctive turns up.

1) There are a set of leading verbs that always change there trailing verbs to the subjunctive. For example, the leading verbs "want", "wish", "prefer", "request/ask for", "suggest", "recommend", "love/like", "think/judge", "be afraid", "demand/command", "let/allow", "advise", "forbid" etc etc. Often with the above there is a particle tà immediately after the leading verb. However tà can be dropped sometimes.

2) After hà "if". For example hà doikos, doikas = If he walks, I will walk

Note the gap between the two parts of the sentence.

The above can be reconfigured a bit ... doikaru hà doikos = I will walk if he walks

Note that the first verb is in indicative form. Also no gap is needed (although you can put one in if you want)

"if only I could walk" ... the exact same construction is used in béu for wishful thinking.

3) As part of stand alone clauses ...

doikas = "should I walk" or "let me walk" or "how about me walking" or "can I walk" or "maybe I should walk"

There is never any need for the question particle ʔai? ... even though some of my translations are questions in English.

doikis = "maybe you should walk" or "why don't you walk" or "how about you walking"

doikos = "let him walk"

doikos jono = "let John walk"

For transitive verbs ...

timpos baus waulo = let the man hit the dog

? = God save the king

diablos ʔawos ò = May the Devil take him

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding bù (or should that be jù). For example ...

bù doikos = best not to let him walk

They locked him up so that he would starve to death

They let him out at night so that he would not starve to death

..

..... Some original thought

..

"WHAT you see is WHAT you get"*

Notice that "you see" and "you get" are not complete clauses, there is a "gap" in them.

The phase "WHAT you see", (to return to the mathematical analogy again) may be thought of as a "variable". in this case, the motivation for using a "variable", is to make the expression "general" rather than "specific". (Being general it is of course more worthy of our consideration). Other motivations for using a "variable" is that the actual argument is not known. Yet another is that even though the particular argument is known, it is really awkward to specify satisfactorily.

Another way to think about the nài construction, is to think of it as a "nominalizer", a particle that turns a whole clause into a noun. To use the example from just above ....

"know" is an intransitive verb with two arguments. To replace one of these arguments by who is like defining the missing argument in terms of the rest of the clause i.e. it changes a clause into a construction that refers to one argument of that clause.

Gap clause particles in other languages

There is no generally agreed upon term for the type of construction which I am calling "gap clause" here. Dixon calls it a "fused relative", Greenberg calls it a "headless relative clause". I don't like either term. A fused relative implies that a generic noun (i.e. "thing" or "person") somehow got fused with a relativizer. This certainly never happened although this type of clause can be rewritten as a generic noun followed by a relativizer. As for "headless" relative clause ... well I think the type of clause that we are dealing with is in fact more fundamental then a relative clause, so I would not like to define it in terms of a relative clause.

My thoughts on this type of clause are ...

Well "what" was firstly a question word. So you have expressions like "Who fed the cat"

Then of course it is natural to have an answer like "I don't know who fed the cat"

Now the above sentence is similar to "I don't know French" or "I don't know Johnny".

Now you see the expression "who fed the cat" fills the slot usually occupied by a noun in an "I don't know" sentences.

So "who fed the cat" started to be thought of as a sort of noun.

Now from the "know (neg)" beachhead*, the usage would have spread to "know" and also the such words that have "knowing" as an essential part of their meaning. Words such as "remember", "report" etc. etc.

*I call "know (neg)" a "beachhead"**. A beachhead is a usage(and/or the act or situation behind that usage) that facilitates the meaning of a word to spread. Or the meaning of an expression to spread. A beachhead can be defined simply as an expression, but sometimes some background as to the speakers environment has to be given. For example suppose that one dialect of a language was using a word to mean "under", but this same word meant "between/among" in all other dialects. Now suppose you did some investigating and found that all other dialects of this language was spoken on the steppes and their speakers made a living by animal husbandry. However the group which diverged from the others had given up the nomadic life and settled down in a lush river valley. In this valley their main occupation was tending their fruit orchards.

It could be deduced that the change in meaning came about by people saying ... "Johnny is among the trees". Now as the trees were thick on the ground and had overspreading branches, this was re-analysed to mean "Johnny is under the trees". Hence I would say ...

The beachhead of word "x" = "between" to word "x" = "under" was the expression "among the trees" (and in this case a bit of background as to the "culture" of the speakers would be appropriate).

For an expressing to become a beachhead, it must, of course, be used regularly.

ASIDE ... I have thought about counting rosary beads as a possible beachhead that changed the meaning of "have", in Western Europe, from purely "possession" to a perfect marker. This is just wild conjecture of course. (The beachhead expression being "I have x beads counted" with "counted" originally being a passive participle)

I am digressing here ... well to get back to "who fed the cat". We had it being considered a sort of noun. Presumably it was at one time put directly after a noun in apposition (presumably with a period of silence between the two) and qualified the noun. Then presumably they got bound closer together, the gap was lost, and this is the history of one form of relative clause in English.

**Actually I would have liked to use the term pivot here. However this term has already been taken.

..

From the dictionary

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 1. A position on an enemy shoreline captured by troops in advance of an invading force

Beachhead (dictionary definition) = 2. A first achievement that opens the way for further developments.

..

..... The Relativizer

There are 4 relativizers ... ʔá, ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja. (relativizer = ʔasemo-marker)

ʔasemo = relative clause.

It works in pretty much the same way as the English relative clause construction. The béu relativisers is ʔá. Though ʔái, ʔáu and ʔaja also have roles as relativisers.

The main relativiser is ʔá and all the pilana can occur with it (well all the pilana except ʔe. ʔaí is used instead of * ʔaʔe).

Note ... we have no direct translation of "whose".

*Altho' this has the same form as all the rest, underneath there is a difference. n marks a noun as part of a noun phrase, not as to its roll in a clause.

As you see in above, ʔa in the form * ʔaʔe is not allowed. Instead you must use ʔaí.

The use of ʔái and ʔàu as relativizers are basically the same as the use of "where" and "when" in English. These two can combine with two of the pilana.

?aifi = from where, whence

?aiye = to where, hence

?aufi = from when, since

?auye = to when, until

The use of ʔaja basically is a relativizer for an entire clause instead of just the noun which it follows.

For example ???????

WITH SPACE AND TIME

PLURAL FORM

..

..... The verb forms

.. The infinitive

..

A verb in its infinitive form (its most basic form) is called maŋga

About 32% of multi syllable maŋga end in "a".

About 16% of multi syllable maŋga end in "e", and the same for "o".

About 9% of multi syllable maŋga end in "au", and the same for "oi", "eu" and "ai".

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk .... not to walk

Where the RHS NP is the O argument and the LHS NP is the A argument.

A maŋga can be an argument in a clause ... just as a seŋko can. For example ...

The kitten playing with the string and the monkey eating the cake was very amusing. ???

(a noun would have the determiner "this", maŋga has the determiner "thus" wedi(if you demonstrate the action)or wede (if someone else demonstrates the action))

???

..

.. The indicative

..

The indicative is the most complicated verb form by far.

The indicative is called the hukəpe

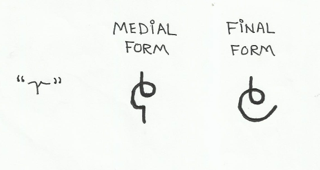

But first we must introduce a new letter.

..

..

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such.

If you hear "r", you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

This "r" and the suffixes attached to it, are what is known as the verb-train (translated from beu)

One quirk of the beu orthography is that all instances of "o" in the verb train are dropped. A quirk of the orthography, not the phonology, so remember to pronounce these "o"s.

..

.. Agent

..

The first piece of information that must be given in the indicative is who does the action. To do this you first ...

1) Deleted the final vowel from the infinitive.

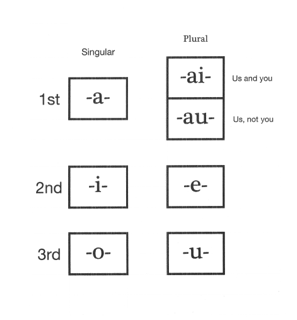

2) Then one of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer..

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikair and doikaur = we walk

doikir = you walk

doiker = you walk

doikr = he/she/it walks ... ( pronounced doikor )

doikur = they walk

..

.. Tense/aspect

..

This section is actually about the tense AND aspect markers of béu.

The bare "r" is for timeless statements, also tends to be used for habitual statements, especially when an adverb of time is mentioned. We can call this the "aortist".

1) doikar = I walk

For the past tense you add "i" after the "r".

2) doikari = I walked

For the future tense you add "u" after the "r".

3) doikaru = I will walk

For the present tense you use the copula and a participle.

4) sar doikala = I am walking

And of course by tensing the copula you can make the following.

5) sari doikala = I was walking

6) saru doikala = I will be walking

For the perfect you add "a" after the "r".

7) doikara = I have walked

And for the pluperfect you add "ai" after the "r".

8) doikarai = I had walked

And for the future perfect you add "au" after the "r".

9) doikarau = I will have walked

And we can apply these last 3 tense/aspect markers to the copula to give ...

10) sara doikala = I have been walking

And of course by tensing the copula you can make the following.

11) sarai doikala = I had been walking

12) sarau doikala = I will have been walking

So there we are ... we have 12 tense/aspect distinctions in all.

[The below is a discussion about the past tense versus the perfect aspect]

The perfect tense, logically doesn't differ that much difference from the past tense,. but it is emphasizing a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have -en".

For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch, this emphasizes the absence of John as opposed to "he went for lunch". The latter is just an action that happened in the past, the former is a present state brought about by a past action.

For another example ... "she read the book on geometry"

This doesn't specify whether she read it all the way thru or whether she just read a bit of it. Whereas ...

"she has read the book on geometry", implies she read the book all the way thru, but more importantly the connotation is that at the present time she has knowledge of geometry.

..

.. Negation

..

To negate any of the above, you add a "j" before the tense/aspect vowel and after the indicative "r".

For the aortist, the negative is formed by adding "jo". For example ...

doikarj = I do not walk ... (pronounced doikarjo)

..

.. Evidence

..

There are three markers that cites on what evidence the speaker is saying what he is saying. You do not have to stipulate on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. Most occurrences of the indicative verb do not have an evidence marker.

The markers are as follows ...

a) doikrin = "I guess that he walked" ... That is, worked out from some clues.

b) doikris = "They say he walked" ....... That is you have been told by some third party.

c) doikria = "he walked, I saw him"

Note that the eye witness evidential only works with the past tense.

For the aortist, the evidence affixes are "on" and "os".

doikrn = I guess that he walks ( pronounced doikoron )

doikrjs = They say she does not walk ( pronounced doikorjos )

..

.. The subjunctive

..

The subjunctive verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "s".

The subjunctive is called the sudəpe

The main thing about the subjunctive is that it is not "asserted" ... it is not insisted upon ... there is a shadow of doubt as to whether the action will actually take place.

This is in contrast to the indicative mood. In the indicative mood things definitely happen.

There are three places where the subjunctive turns up.

1) There are a set of leading verbs that always change there trailing verbs to the subjunctive. For example, the leading verbs "want", "wish", "prefer", "request/ask for", "suggest", "recommend", "love/like", "think/judge", "be afraid", "demand/command", "let/allow", "advise", "forbid" etc etc. Often with the above there is a particle tà immediately after the leading verb. However tà can be dropped sometimes.

2) After hà "if". For example hà doikos, doikas = If he walks, I will walk

Note the gap between the two parts of the sentence.

The above can be reconfigured a bit ... doikaru hà doikos = I will walk if he walks

Note that the first verb is in indicative form. Also no gap is needed (although you can put one in if you want)

"if only I could walk" ... the exact same construction is used in béu for wishful thinking.

3) As part of stand alone clauses ...

doikas = "should I walk" or "let me walk" or "how about me walking" or "can I walk" or "maybe I should walk"

There is never any need for the question particle ʔai? ... even though some of my translations are questions in English.

doikis = "maybe you should walk" or "why don't you walk" or "how about you walking"

doikos = "let him walk"

doikos jono = "let John walk"

For transitive verbs ...

timpos baus waulo = let the man hit the dog

SAVE GOD KING ????????? = God save the king

diablos ʔawos ò = May the Devil take him

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding ka. For example ...

doikoska = best not to let him walk

It is a convention in beu that the "a" is always dropped. I will follow that convention in my transliteration. So ... doikosk from now on.

They locked him up so that he would starve to death

They let him out at night so that he would not starve to death

..

.. The imperative

..

This is used for giving orders. When you utter an imperative you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action (although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible).

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

1) First the final vowel of the infinitive is deleted and replaced with u.

doika = to walk

doiku = walk !

For monosyllabic verbs u is prefixed.

gàu = to do

ugau = do it !

The negative imperative is formed by putting the particle kyà before the infinitive.

kyà doika = Don't walk !

..

..... le lu and lo

..

Earlier we have seen that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilana affixed. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilana then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

jonos jenes solber moʒi = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of affixed pilana, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lé can be placed between them.

This word is that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

Another similar particle is lú meaning "or". Its also has a special symbol. See below ...

jenes blor solbe moʒi lú ʔazwo = "Jane can drink water or milk"

jonos jenes bwuri hói sadu lè léu ʔusʔa faja dí = John and Jane saw two elephants and three giraffes this morning.

In béu, as in English, if it is obvious to the listener that a string of nouns are going to be given then they can be spoken with just a slight pause between them. However lè must always separate the last from the second last. But having lè between every member of a list is also permissible.

jenes bwori hói sadu _ léu ʔusʔa _ uga moŋgo lè ilda gaifai faja dí = Jane saw two elephants, three giraffes, four gibbons and five flamengos this morning.

..

lò = other

kyulo = again

lowe = otherwire

..

..... kolape

This is a complement clause construction. In English there are 7 types of complement clauses, in béu there are only 3.

A complement clause is call a kolape in béu. The three types are briefly summarised below and then each of the types is discussed in more detail.

1) I remembered writing the book ... this conveys that the whole process of locking the door is going thru the speakers mind ... ???ari pá kludau toili

The béu form above looks similar to the English "I remembered to write the book". However this is NOT the meaning.

To say "I remembered to write the book" in béu you would say ???ari tá toili (rà) kludu ... see the section about participles.

2) I thought that I wrote the book ... takes the same form in béu ... olgari tá kludari toili

3) He asked me whether I had written the book ??? ... askori (pavi) tavoi kludari toili

kolape jù

In béu the word order is usually free. This is not true in a kalope jù

jonoS rì kéu = John was bad

(pà solbe moze pona sacowe)S rì kéu = my drinking the cold water quickly was bad

Notice that pà solbe moze pona sacowe behaves as one element. It has the same function as "John" in the previous example.

The word order inside kolape jù is fixed. It must be S V or A V O for a transitive clause (any other peripheral arguments are stuck on at the end).

Also notice that the ergative marker -s which is usually attached to the A argument is dropped. Actually for pronouns it is not just the dropping of the -s, but a change of tone also, so this form is identical to the O form of the pronoun.

The kolape above, if expressed as a main clause would be.

(pás) solbari saco* moze pona = I drank the cold water quickly

Other examples ;-

wàr solbe (I want to drink) is another example. (wò = to want)

klori jono timpa jene (he saw John hitting Jane) ... (klói = to see)

kolape jù? can be considered as a noun phrase and the fixed ordering of elements can be seen as a reflextion of the strict order of elements in a normal noun phrase

Subject1 Head2 Object3(Peripheral arguments4 x n)

1) The "A" argument or the "S" argument.

2) The verb.

3) The "O" argument, which would of course be non-existent in an intransitive clause.

4) Adverbs and everything else.

A gomia such as solbe can be regarded as a proper noun** and can be the head of a cwidauza (see a previous section)

or it can be the head of a kalope jù. But these two constructions are always distinct. For example you couldn't append a determiner to a kalope jù ... (or could you ??)

* in a main clause the adverb can appear anywhere if suffixed with -we. But in kalope jù the adverb must come after the Subject, Verb and Object.

** A gomia never forms a plural or takes personal infixes in the way a normal noun does. Also it only takes a very reduced subset of pilana, so a gomia can be regarded as an entity half way between nounhood and verb hood. For that reason I consider gomia as a part of speech, standing alongside "noun" and "verb".

kolape tá

In this form the full verb* is used, not the gomia. Also we have a special complementiser particle tá which comes at the head of the complement clause.

wàr tá jonos timporu jene = I want John to hit Jane

klori tá jonos timpori jene (he saw that John hit Jane) ... (klói = to see)

*Well not quite the full form. Evidentials are never expressed.

kolape tói

This is equivalent to English word "whether".

sa RAF kalme Luftwaffe kyori Hitler olga tena => The RAF's destruction of the Luftwaffe, made Hitler think again. ... here a gomiaza acts as the A-argument.

*in the combinations where sacowe immediately followed solbe it is merely saco

Things to think about

what is a gomiaza

Can this be used for a causative construction ??

..... The parts of speech of béu

"Parts of speech" is linguistic jargon, which is referring to the different "classes" of words a language might have. For example "nouns", "verbs", etc. etc.

In fact nouns (N), verbs (V) and adjectives (A) are the big three, and after some debate over the last 30 years, it has been agreed that every language has these three word classes.

In béu a noun is called cwidau (cwì meaning a physical object), a verb is called jaudau (jàu meaning "to move"), and an adjective is called saidau (sài meaning "a colour").

There are other classes of words in béu as there are in other languages. béu has adverbs (wedau) but these don't really come into their own, being more a form an adjective takes in certain situations. Also a lot of words that are called adverbs in English are called particles (feŋgia) (F) in béu. Particles are a type of hold-all category for a word that doesn't fit into any of the other classes. Under the term "particle" many subclasses can be defined, and in fact some subclasses have a class membership of one. If you come across a word that can not easily be equated with any of the major word classes ... well then you probably have a feŋgi.

It is necessary to talk about another part of speech which I will refer to by the béu term helgo* (G). It is a form of the verb which is called the "infinitive" in the Western linguistic tradition.

The reason for this is that a verb in a sentence functioning as verbs commonly do, has person, number, tense, aspect and evidentiality expressed on the verb as series of suffixes, hence the "tail". These items are not expressed on the helgo.

For example solbarin (I drank, so they say) is a helgo.

solbarin is built up from the ma solbe" ... first you delete the final vowel => then you add "a" meaning first person singular subject => then you add "r" meaning that the mood is indicative (as opposed to imperative or subjunctive) => then you add "i" meaning simple past tense => and finally you add "n" which is an evidential, meaning that the utterance is based on what other people have said.

solbarin is manka pomo or "a full tail verb".

The three evidential markers are all optional, so they can quite easily be dropped. solbari (I drank)

solbis (you lot drink) and solbon (let him drink) ... the first is an example of the imperative and the second is an example of the subjunctive (more linguistic jargon ... sorry).

solbai is called an part verb ???

== ..... Another relativizer

There is another relativized in béu that refers back to a whole proposition. In English "which" is sometimes given this function. For example ...

1) ... John had completely forgotten his wedding anniversary which really annoyed his wife.

béu uses nài in a similar way to how which is used in the above example. Also the same shorthand form is used for nài and nái. However no misunderstanding is possible since nài always has a pause before it (how do I do a comma ?) and nái always is immediately after a noun.

Mmmh ... Three verb based phrases

These "set the scene" for the main clause.

1) habitual aspect

2) perfect aspect

3) has "future participal" or "modal" meaning ...

The plovaza (adjective phrase) is a clause that sets the scene for the main action.

1) "waiting on tables six nights a week", Kirsty had come to know all the regular customers // "their mains flowing", they ran across the field and down to the river.

2) "his leg broken", he slowly crawled up the sand dune and ...

3) "having to pack all the stereos before lunch", he did not stop for a tea-break.

In beu we could have

1) fi plus dead verb phrase

2) tu plus wai participle.

3) tu plus "all the stereos packwau before lunch.

In English grammar this is called a nominative absolute construction. It is a free-standing (absolute) part of a sentence that describes or modifies the main subject and verb. It is usually at the beginning or end of the sentence, although it can also appear in the middle. Its parallel is the ablative absolute in Latin, or the genitive absolute in Greek.

Noun Phrase

This is a noun. For example bàu "man"

Sometimes the head can be dropped. When this happens, sometimes the particle à will stand in for the actual noun.

When the dropped noun is plural, the particle á is used.

Whether these particles are used or not, depends on what is the most important part of the NP left after the noun is dropped.

The order of importance is "adjective" then "determiner" then "RC" ...

When the most important remaining component is an adjective, then you must use the particle. So ...

à gèu = the green one

á gèu = the green ones

à gèu bòi = the green one is good

When the most important remaining component is an determiner, then you can either use the particle or drop the particle. So ...

à dè bòi = that one is good

á dè bòi = these are good

[ dè bòi = that is good .... referring to a statement or a situation ?? ]

Utterance initial you nearly always find the particle before the determiner.

[ But what about numbers ?? ]

No particle is used with RC's

Depository for béu linguistic terms

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the Western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she). In the béu linguistic tradition they are called cenʔo-markers. (cenʔo = musterlist, people that you know, acquaintances, protagonist, list of characters in a play)

These markers represent the subject (the person that is performing the action). Whenever possible the pronoun that represents the subject is dropped, it is not needed because we have that information inside the verb with the cenʔo-markers.

Now these markers represent what are called tense/aspect markers in the Western linguistic tradition. In the béu linguistic tradition, they are called gwomai or "modifications". (gwoma = to alter, to modify, to adjust, to change one attribute of something).

4) and finally one of the 4 teŋko-markers shown below is added.

teŋkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate" ... teŋko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

By the way, the béu terms for the five aspects represented by these 5 rows are ... baga, dewe, liʒi, pomo and fene ... i.e. in the tense/aspect table.

..

Pondering the subjunctive

..

I think the first verb we learn when we are growing up. And it retains its importance to us all thru life. I thought it deserves a section to itself.

Maybe I should forget about the subjunctive (ends in xn, before ended in xs, maybe should end in xk) and do things another way ??

The transitivity of verbs in béu

..

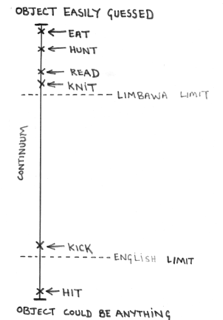

All languages have a Verb class, generally with at least several hundred members.

Leaving aside copula clauses, there are two recurrent clause types, transitive and intransitive. Verbs can be classified according to the clause type they may occur in: (a) Intransitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of an intransitive clause; for example, "snore" in English. (b) Transitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of a transitive clause; for example, "hit" in English. In some languages, all verbs are either strictly intransitive or strictly transitive. But in others there are ambitransitive (or labile) verbs, which may be used in an intransitive or in a transitive clause. These are of two varieties: (c) Ambitransitives of type S = A. An English example is "knit", as in "SheS knits" and "SheA knits socksO". (d) Ambitransitives of type S = O. An English example is "melt", as in "The butterS melted" and "SheA melted the butterO".

English verbs can be divided into the four types mentioned above. béu verbs however can only be divided into two types, a) Intransitive, and b) Transitive. In this section it will be shown how the four English types of verb map into the two béu types. (Of course there is nothing special or unique about English ... other than the fact that a reader of this grammatical sketch will already be familiar with English)

..

intransitive

..

An intransitive verb in English => an intransitive verb in béu

..

An example of an intransitive verb in English is "laugh". This is also an intransitive verb in béu. In a clause containing an intransitive verb, the only argument that you have is the S argument.

By the way ... some concepts that are adjectives in English are primarily intransitive verbs in béu, for example ;- to be angry, to be sick, to be healthy etc. etc.

Ambitransitive of type S=O

..

| x) An intransitive in béu | |

| An "ambitransitive of type S=O" => | y) A pair of verbs, one being intransitive and one being transitive |

| z) A transitive in béu |

..

x) "Ambitransitive verbs of type S=O" which have greater frequency in intransitive clauses, are intransitive verbs in béu.

For example ;- flompe = to trip, (ò)S flomporta = She has tripped

y) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which are frequent in both transitive and intransitive clauses, are represented as a pair of verbs in béu, one of which is intransitive and one transitive. There are a few hundred béu verbs that come in pairs like this. One should not be thought of as derived from the other; each form should be considered equally fundamental. All the pairs have the same form, except the transitive one has an extra "l" before its final consonant.

For example hakori kusoniS = his chair broke : (pás)A halkari kusoniO = I broke his chair :

z) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which have greater frequency in transitive clauses, are transitive vebs in béu.

For example ;- nava = to open, (pás)A navaru pintoO = I am going to open the door

Ambitransitive verbs of type S=A and Transitive verbs

.

.

| An "ambitransitive of type S=A" | |

| or | => A transitive in béu |

| A transitive verb in English |

. .

I am taking transitive and ambitransitive of type (S=A) together as I consider them to be basically the same thing but tending to opposite ends of a continuum.

Consider the illustration below.

At the top (with the "objects easily guessed") are verbs that are normally designated "ambitransitive of type S=A".

At the bottom (with the "objects could be anything") are verbs that are normally designated "transitive".

.

.

Considering the top first. One can have "IA eat applesO" or we can have "IS eat"

Then considering the bottom. One can have "IA hit JaneO" but you can not have "*IS hit"

Moving up from the bottom. One can imagine a situation, for example when showing a horse to somebody for the first time when you would say "SheS kicks". While this is possible to say this, it is hardly common.

As we go from the top to the bottom of the continuum;-

a) The semantic area to which the object (or potential object if you will) gets bigger and bigger.

b) At the bottom end the object becomes is more unpedictable and hence more pertinent.

c) As a consequence of a) and b), the object is more likely to be human as you go down the continuum.

béu considers it good style to drop as many arguments as possible. In béu all the verbs along this continuum are considered transitive. Quite often one or both arguments are dropped, but of course are known through context. If the O argument is dropped it could be known because it was the previously declared topic (however more often the A argument is the topic tho', and hence dropped, represented by swe tho' as its case marking can not be dropped), it could be because the verb is from the top end of the continuum and the action is the important thing and the O argument or arguments just not important, or the dropped argument could be interpreted as "something" or "somebody", or it could be a definite thing that can be identified by the discouse that the clause is buried in.

Ambitransitive verbs

fompe is an intransitive and a transitive verb (S and A)

jene fompori = Jane tripped

jonos fompori jene = John tripped Jane

halka is an intransitive and a transitive verb (S and O)

pintu halkori = the door broke

jonos pintu halkori = John broke the door

A list of 6 ambitransitive (S and A) verbs

tonza = to awaken, to wake up

henda = to put on clothes

laudo = to wash

poi = "to enter" or "to put in"

gau = "to rise" or "to raise"

sai = "to descend" or "to lower"

To recognize as a transitive clause you must look for the ergative -s, if no -s then we have an intransitive clause.

Or alternatively you must look for the particle kyebwo

Tom Jerry halkuri = Tom and Jerry broke

Tom Jerry halkuri kyebwo = Tom and Jerry broke one and other.

ké = result, consequence

bò = case, example, instance

hí = source, origin

Now while these words are still used as nouns, they have developed a longer form ... possibly to reduce ambiguity with the particulate usage.

ké => kegozo = result, consequence ... (gozo = fruit)

bò => bozomba = case, example, instance ... (somba = to sit)

hí = => hidito = source, origin ... (dito = point, dot)

..... -am- as a none-productive infix

klói = to see

klamoi = to show

tàu = to know

tamau = to tell

bái = to go, to move

bamai = to drive

kàu = to come

kamau = to summon

fyu = to fly

fyamu = to throw

gwoi = to jump (involuntarily), to give a start

gwamoi = to make somebody jump, to give somebody a start

doika = walk

damoika = to manage, to run ......... damoikanai = "the management" or "the managers"

..

..... Start, Stop, Try

In béu, three secondary verbs (in English) are expressed by a copula plus a pilana. They are ...

to start drinking => láu solbelke

to stop drinking => láu solbelfe

to try drinking => sàu solbewo

And just to demonstrate that the above doesn't necessary lead to confusion ...

He talks about drinking => cator solbewo

We talk about trying to drink => catair wo sàu solbewo

So in fact the gomia take 8 of the 12 pilana ... ji ge n ho la lfe lkx wo

The ergative s also occurs but only in its prepositional form sá

..

..... two more copula

There are 2 more words that might be considered copula ...

1) twài = to be located, to be placed .... perhaps an eroded form of a participle of tèu "to place"

2) yór = to exist ... a third person indicative form of the verb yái "to have". The third person indicative meaning is completely bleached in this usage.

..... must should can know how to

Also often called the predicate. Called the jaudauza in béu

The predicate is made up of ...

1) one of two particles that show likelihood which are optional.

In the béu linguistic tradition they are called mazebai. The mazebai are a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles)

2) one of five particles that show modality. These are also optional.

In the béu linguistic tradition they are called seŋgebai. The seŋgebai are a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles)

3) a gomua (a full verb)

... mazebai

These appear first in the predicate.

These particles show the probability of the verb occurring.

1) màs solbori = maybe he drank

2) lói solbori = probably he drank

You could say that the first one indicates about 50% certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty

... seŋgebai

These appear next in the predicate.

These particles correspond to what is called the "modal" words in English. The five seŋgeba are ...

1) sú which codes for strong obligation or duty. It is equivalent to "should" in English. In English certain instances of the word "must" also carries this meaning.

2) seŋga which codes for weak obligation. It is equivalent to "ought to" in English. (Note ... in certain dialects of English "ought to" is dying out, and "should" is coding weak obligation also)

3) alfa which codes for ability. It is equivalent to "can" in English. As in English it means that subject has the strength or the skill to perform the action. Also as in English it codes for possibilities/situations which are not dependent on the subject. For example ... udua alfa solbur => "the camels can drink" in the context of "the caravan finally reached Farafra Oasis"

4) hempi which codes for permission. It is equivalent to "may" or "to be allowed to" in English. (Note ... in certain dialects of English "may" is dying out, and "can" is coding for permission also)

5) hentai means knowledge. It is equivalent to "know how to" in English. (Note ... in English certain instances of the word "can" also carries this meaning)

The form that these seŋgeba and the main verb take appears strange. Where as, logically, you would expect the suffixes for person, number, tense, aspect and evidential to be attached to the seŋgeba and the main verb maybe in its infinitive form, the seŋgeba do not change their form and the suffixes appear on the main verb as normal. This is one oddity that marks the seŋgeba off as a separate word class.*

Some examples ...

1)

a) sú -er => you should visit your brother

b) sú -eri => you should have visited your brother

c) sú hamperka animals => you should not feed the animals

d) sú hamperki animals => you shouldn't have fed the animals

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza súa

2)

a) seŋga humper little => you ought to eat a little

b) seŋga humperi little => you ought to have eaten a little

c) seŋga solberka brandy => you ought to not drink brandy

d) seŋga solberki brandy => you ought to have not drunk that brandy

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza seŋgua

3)

a) fuà -or => he can swim across the river

b) fuà-ori => he could swim across the river

c) fuà solborka => he can stop drinking

d) fuà solborki => he could stop drinking

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza fùa

4)

a) hempi bor festa => "she may go to the party" or "she can go to the party" or "she is allowed to go to the party"

b) hempi bori festa => she was allowed to go to the party

c) hempi borka school => he is allowed to stop attending school

d) hempi bori school => he was allowed to stop attending school

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza hempua

5)

a) hentai bamor car => "she can drive a car" or "she knows how to drive a car"

b) hentai bamori car => she knew how to drive a car

c) hentai boikorka car => He has the ability not to crash the car

d) hentai boikorki car => He had the ability not to crash the car

Note these are the tenses allowed in a jaudauza hentua

*Two other oddities also marks off the seŋgeba as a separate word class. These are ...

1) When you want to question a jaudauza containing a seŋgeba you change the position of the main verb and the seŋgeba. For example ...

bor hempi festa => "may she go to the party" ... shades of English here.

2) All 5 seŋgeba can be negativized by deleting the final vowel and adding aiya. For example ...

faiya -or ??? => he can't swim across the river

Note ... sometimes the negative marker on the seŋgeba can occur along with the normal negative marker on the main verb to give an emphatic positive. Sometimes it produces a quirky effect. For example ...

jenes faiya humpor cokolate => Jane can't eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability to eat chocolates) ... for example she is a diabetic and can not eat anything sweet.

jenes fa humporka cokolate => Jane can not eat chocolates (Jane have the ability not to eat chocolates)... meaning she has the willpower to resist them.

jenes faiya humporka cokolate => Jane can not not eat chocolates (Jane lacks the ability, not to eat chocolates) ... meaning she can't resist them.

There are 5 nouns that correspond to the 5 seŋgeba

anzu = duty

seŋgo = obligation

alfa = ability

hempo = permission or leave

hento = knowledge

Note on English usuage (in fact all the Germanic languages) ... the way English handles negating modal words is a confusing. Consider "She can not talk". Since the modal is negated by putting "not" after it and the main verb is negated by putting "not" in front of it, this could either mean ...

a) She doesn't have the ability to talk

or

b) She has the ability to not talk

Note only when the meaning is a) can the proposition be contracted to "she can't talk". In fact, when the meaning is b), usually extra emphasis would be put on the "not". a) is the usual interpretation of "She can not talk" and if you wanted to express b) you would rephrase it to "She can keep silent". This rephrasing is quite often necessary in English when you have a modal and a negative main verb to express.

... wepua

We have already mentioned the two mazeba at the beginning of this section.

Actually there is another particle that occurs in the same slot as the mazeba and it also codes for likelihood. This is wepua and it constitutes a subgroup of feŋgi (the particles) all by itself.

1) más solbori = maybe he drank

2) lói solbori = probably he drank

3) wepua solbori = he must have drank

You could say that while the first one indicates about 50% certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty, the third shows 100% certainty.

3) Indicates that some "evidence" or "background information" exists to allow the speaker to assert what he is saying. It also carries the meaning "there is no other conclusion given the evidence".This obviously has some functional similarities to the -s evidential. However the -s evidential carries less than 100 % certainty ...

solboris = I guess/suppose he drunk

wepua never appears in front of the first two seŋgebai. This is the difference between wepua and the mazebai.

The word wepua is derived from pè meaning "to need". pòi means necessities.wepua can be thought of as meaning something like "being necessary" or "of necessity".

The reciprocal construction

..

The reciprocal particle can be said to historically come from both náu and mài.

jonos jenes timpura namai = "John and Jane are hitting each other" = "John and Jane hit one and other"

namai the reciprocal particle (usually comes immediately after the verb) is obviously derived from the phrase náu mài

Note ... lè "and" is not used when two nouns in the ergative case occur adjacent to each other.

..

.... -fa, and -inda

These all form adjectives. The first might have some connection with a seŋgeba.

i.e. solbe = to drink

moze = water

moze solbefa = drinkable water

Maybe related to fua "can".

moze solbinda = water worth drinking

There is also another suffix, but this one can be said to be unrelated to "like" kinda

Maybe related to kinda "to like".

..

..... Machine symbols

The "béu.symbol" is a orange disk with a sky blue background (the "béu.symbol" has both a simple and a complex representation)

This imagery continues into the way that machines are marked ...

To show that a machine is working, an orange disc is illuminated To show that a machine is switched off, a sky blue square is illuminated

The button to switch a machine on, is an orange disk with a black ring on it The button to switch a machine off, is a sky blue square with a black ring on it

( Of course the functions of indication and switching are often combined in one button )

For rocker switches ( such as light swithes ) the top part is square and you push this to switch off ... the bottom part is semicircular and you push this to switch on

By the way "red" is associated with danger and "green" is associated with safety So for example traffic lights are exactly the same ( including the orange in the middle )

By the way there are no other associations with colour ... you do not talk about a blackheart or a yellow streak etc etc ... kids are not split up according to pink or blue clothes.

YĪN YÁNG

femininity masculinity

the moon the sun

the earth the sky

diffuseness focused

femininity masculinity

soft hard yielding solid passive aggressive/active fast slow

the moon the sun black white cold hot wet dry water fire nightime daytime

Strictly NO association between "order"/"chaos" and the concepts not highlighted.

Also no associations with ...

good bad truth falsehood right wrong north south beauty uglyness positive negative right left

..... Introduction

The language and culture of béu are listed in the 10 chapters that follow. At the moment only the first chapter can really be considered finished ... at least as far as the language goes. Approximately the first 13 pages of every chapter concern the language and the last 6 pages or so concern the culture.

The cultural sections seem to be pretty solid at the moment but the linguistic sections are still in flux. Hopefully in the not too distant future the language will become equally solid.

In this introduction, I first discuss the language. Then I discuss some of the foundations of the culture of béu. Finally I mention some of the more esoteric bits of the culture.

..

A history of the Language ...

The very first language that I tried to construct was called HARWENG. This was eventually given up about 14 years ago. The basic problem was that I didn't know enough about linguistics. "if you want to get high, you first must build a strong foundation" When I tried to build on the foundations that I had established, I found too many things just didn't harmonise : it seemed like an impossible task to cut though the tangles, so I put that project reluctantly aside.

My second project was called SEUNA. The reason that I put this one aside was that I wasn't too happy with the SEUNA script. However my third language ... BEU (from now on referred to as béu ... by the way, the diacritic above the "e" indicated a high tone) seems like it will carry on to fruition.

What interests me most in linguistics is that fascinating area where logic, grammar and semantics intersect. I appreciate the elegant patterns that are found in natural languages. However most natural languages have elements which I don't like. Such as the tendency of natural languages to appropriate existing grammatical particles when evolving a new structure. Probably the forces that drive natural language change are fundamentally unable to form a language sufficiently "efficient" and "elegant" for me ... evolution by "decree" rather than natural forces just seems so much more easy.

Also I have always been a perfectionist ... keenly aware of all the imperfections that everyday life entails. I have always had the feeling that in order to build perfection you must start at the very bottom ... and I also have had the feeling that language is the most basic thing* that makes us human. Hence the first step to making a better world is to develop a logical, elegant and beautiful language.

All of the above motivated me to construct a new language.

The best constructed language which I have so far come across was CEQLI. However it was not much more than a sketch. Also the two languages created by Dirk Elzinga ... TEPA and SHEMSPREG were also very neat. However again they were not fully thought out ... not complete languages. I intend that béu will be a fully formed language.

..

The "bubble fountain" above is how I see the world 4,000 languages (OK I haven't drawn 4,000 bubbles ... pretend) of the world. The vertical axis is complexity. The black line at the bottom represents zero ... the way that a group of people would communicate initially if they all spoke totally different languages and were forced to associate together by some twist of fate. There would be zero grammaticisation ... it would be a very inefficient means of communication and I would presume quite frustrating to try and converse in. The horizontal axis represents how far the different languages diverge from each other (this "divergence" should be multi-dimensional because of course languages diverge from each other in many many different ways ... but I am afraid we must make do with one dimension on my little chart).

You will notice that the simple languages at the bottom of the chart differ less from each other less than the more complex languages at the top. These simple languages tend to have one concept to one word ... they are analytic. Now a simple language is just as fit-for-purpose as a complicated language. And I certainly didn't want complexity for complexity's sake : I just wanted a language that was easy to learn and that would appear to be "natural". Hence the structure of béu is not a million miles away from the structure of English ... or Mandarin. In its final form béu seems like a natural language : the grammar and the "patterns" in the language wouldn't be considered out of place in a natural language.

In its long history (HARWENG => SEUNA => béu) it has changed many many times. It has gone thru' many iterations**. I would change one part of the grammar and then find that this change didn't fit with something else. So I would change it back, or modify the "something else", or maybe try out a completely new paradigm. This happened many many times. I suppose the changes that happened in in the development of béu are similar to the diachronic changes that happen to natural languages, and hence béu ended up looking quite naturalistic.

* I believe that language co-evolved with the increase in the human cranial capacity ... so language has been with us for well over a million years.

** A good analogy to this how a protein takes its shape. This is a long linear chain molecule that folds up on itself to takes on a very definite and complicated shape. The final shape is determined by a series of movements that are initiated by the attractive and repulsive forces that the various links in the chain have for each other. In a similar way the final shape of béu was determined by the way that different grammatical patterns and phonological patterns either clashed with each other, or matched with each other through a number of successive iteration.

..

Addendum ... When talking about grammar I follow the lead given by R.M.W. Dixon in "Basic Linguistic Theory". I would thoroughly recommend this book. As well as giving a broad topological perspective of the World's languages, it puts the convoluted terminology that has grown up in the field of linguistics over the years, firmly in its place.

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences