Béu : Chapter 5: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 681: | Line 681: | ||

.. | .. | ||

===The transitivity of verbs in '''béu'''=== | |||

The | |||

''' | |||

All languages have a Verb class, generally with at least several hundred members. | All languages have a Verb class, generally with at least several hundred members. | ||

| Line 906: | Line 822: | ||

Tom Jerry '''halkuri kyebwo''' = Tom and Jerry broke one and other. | Tom Jerry '''halkuri kyebwo''' = Tom and Jerry broke one and other. | ||

-------------------- | |||

'''ké''' = result, consequence | |||

'''bò''' = case, example, instance | |||

'''hí''' = source, origin | |||

------------------------- | |||

Now while these words are still used as nouns, they have developed a longer form ... possibly to reduce ambiguity with the particulate usage. | |||

'''ké''' => '''kegozo''' = result, consequence ... ('''gozo''' = fruit) | |||

'''bò''' => '''bozomba''' = case, example, instance ... ('''somba''' = to sit) | |||

'''hí''' = => '''hidito''' = source, origin ... ('''dito''' = point, dot) | |||

== ..... Word building== | == ..... Word building== | ||

Revision as of 22:30, 17 December 2015

..... The three types of Verb

..

Some concepts are naturally transitive. Like "to hit". It is very rarely that someone hits themselves.

Some concepts are naturally intransitive. Like "to shave".

And there are also some concepts that appear in both manifestations. For example ... "turn", "spread", "rise/raise"

These three types of concept are represented in beu by three different types of verb.

timpa = to hit ... this is a transitive verb ... (designated as V1 from now on)

dwé = to come ... this is a intransitive verb ... (designated as V2 from now on)

haika/heuka = to break .... this concept has two forms ... the first is transitive, the second inansitive.

We will designate haika as V3a and heuka as V3b.

Notice that in English a change in vowel with the pair "rise"/"raise" indicate a change in transitivity. beu also uses this method but with a lot more regularity.

| intransitive | transitive |

| au | oi |

| eu | ai |

| o | i |

| u | e |

Notice that the intransitive version has a verb ending in an back vowel and the the transitive version has a verb ending in an front vowel. So if you see haika (V3) you know that you have a transitive verb.

Also notice V3 never have a ua or ia as their main vowels.

Now lets lay out the derivations possible with these different verb types.

..

.. V1 Derivations

..

There are 5 deriuvation processes shown below ...

First from kludau => kludawau This involves infixing aw before the final vowel.

Secondly from kludau => kludana and kludawau => kludawana.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding ana.

Thirdly from kludau => kludala and kludawau => kludawala.

This involves deleting the second part of the final vowel if it is a diphthong, and then adding la.

Fourthly from kludau => kludwai.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding wai.

Fifthly from kludau => kludwau.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding wau.

..

| kludawana | <============ | kludawau | ============> | kludawala |

| "computer memory" (N) | "to be written" (V2) | "being written" (A) | ||

| ^ | ||||

| | | ||||

| | | ||||

| kludana | <============ | kludau | ============> | kludala |

| "writer" (N) | "to write" (V1) | "writing" (A) | ||

| kludwai | kludwau | |||

| "written" (A/N) | "which must be written" (A/N) |

..

kludwai is the passive past participle, and kludwau is the passive future participle.

..

Note that we have 8 word forms in total.

..

.. V2 Derivations

..

There are 5 deriuvation processes shown below ...

First from doika => doikaya This involves infixing ay before the final vowel.

Secondly from doika => doikana and doikaya => doikayana.

This involves deleting the final vowel and adding ana.

Thirdly from doika => doikala and doikaya => doikayala.

This involves deleting the second part of the final vowel if it is a diphthong, and then adding la.

Fourthly from doikaya => doikaiwai.

This involves deleting the final vowel and y and adding iwai.

Fifthly from doikaya => doikaiwau.

This involves deleting the final vowel and y and adding iwau.

..

| doikaiwai | doikaiwau | |||

| "that which has been made to walk" (A/N) | "that which must be made to walk" (A/N) | |||

| doikayana | <============ | doikaya | ============> | doikayala |

| "the one that makes walk" (N) | "to make to walk" (V1) | "causing to walk" (A) | ||

| ^ | ||||

| | | ||||

| | | ||||

| doikana | <============ | doika | ============> | doikala |

| "walker" (N) | "to walk" (V2) | "walking" (A) |

Note that we have 8 word forms in total.

..

.. V3 Derivations

..

| haikana | <============ | haika | ============> | haikala |

| "breaker" (N) | "to break" (V3a) | "breaking" (A) | ||

| haikwai | haikwau | |||

| "broken" (A/N) | "that which must be broken" (A/N) |

..

Note ... haikwai could very well have broken by itself. There is no connotation that an outside agent was responsible. The same with haikwau.

..

| heukana | <============ | heuka | ============> | heukala |

| "breaker" (N) | "to break" (V3b) | "breaking" (A) |

..

There are 4 derivational processes involved with V3a and 2 derivational processes involved with V3b. They have been already been explained in the sections on V1 and V2.

Note that we have 8 word forms in total.

kó = to see

kowa = to be seen

The subject of the active clause, can be included in the passive clause as an afterthought if required. hí is a normal noun meaning "source". However it also acts as a particle (prefix) which introduces the agent in a passive clause.

poʔau = to cook

..

When the final consonant is w y h or ʔ the passive is formed by suffixing -wa

In monosyllabic words, it is formed by suffixing -wa.

Note ... when wa is added to a word ending in au or eu, the final u is deleted.

Also note ... these operations can make consonant clusters which are not allowed in the base words. For example, in a root word -mpw- would not be allowed ( Chapter 1, Consonant clusters, Word medial)

..

... Valency ... 1 => 2

..

Now all verbs that can take an ergative argument can undergo the 2=>1 transformation.

There also exists in béu a 1=>2 transformation. However this transformation can only be applied to a handful of verbs. Namely ...

| ʔoime | to be happy, happyness | ʔoimora | he is happy | ʔoimye | to make happy | ʔoimyana | pleasant |

| heuno | to be sad/sadness | heunora | she's sad | heunyo | to make sad | heunyana | depressing |

| taudu | to be annoyed | taudora | he is annoyed | tauju | to annoy | taujana | annoying |

| swú | to be scared, fear | swora | she is afraid | swuya | to scare | swuyana | frightening, scary |

| canti | to be angry, anger | cantora | he is angry | canci | to make angry | cancana | really annoying |

| yodi | to be horny, lust | yodora | she is horny | yoji | to make horny | yojana | sexy, hot |

| gái | to ache, pain | gayora | he hurts | gaya | to hurt (something) | gayana | painful * |

| gwibe | to be ashamed/shame/shyness | gwibora | she is ashamed/shy | gwibye | to embarrass | gwibyana | embarrassing |

| doimoi | to be anxious, anxiety | doimora | he is anxious | doimyoi | to cause anxiety, to make anxious | doimyana | worrying |

| ʔica | to be jealous, jealousy | ʔicora | she is jealous | ʔicaya | to make jealous | ʔicayana | causing jealousy |

ʔoimor would mean "he is happy by nature". All the above words take this sense when the "a" of the present tense is dropped.

The above words are all about internal feelings.

The third column gives a transitive infinitive (derived from the column two entry by infixing a -y- before the final vowel).

The fourth column gives an adjective of the transitive verb (derived from column three entry by affixing a -ana ... the active participle).

When the final consonant is ʔ j c w or h the causative is formed by suffixing -ya.

Also when the verb is a monosyllable, the causative is formed by suffixing -ya.

Note ... when ya is added to a word ending in ai or oi, the final i is deleted.

Note ... when y is infixed behind t and d : ty => c and dy => j

There is one other word that follows the same paradigm as the 10 words above.

| jùa | to know | jor | he knows | juya | to tell | juyori | she has told |

..

Normally in béu, to make a nominally intransitive verb transitive, it doesn't need the infixing of -y. All it needs is the appearance of an ergative argument. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikor = he walk

ós doikor the pulp mill = he runs the pulp mill

doikyana = management ???

..

*You would describe a gallstone as gayana. However you would describe your leg as gaila (well provided you didn't have a chronic condition with your leg)

..

Concatenation of the valency changing derivations ... 1 => 2 => 1 and 2 => 1 => 2

..

| ʔoime | = to be happy | ʔoimye | = to make happy | ʔoimyewa | = "to be made to be happy" or, more simply "to be made happy |

..

| fàu | = to know | fa?? | = to tell | fa ?? | = |

..

| timpa | = to hit | timpawa | = to be hit | timpawaya | = to cause to be hit |

..

Semantically timpa is direct action (from agent to patient). Whereas timpawaya is indirect, possibly involving some third party between the agent and the patient and/or allowing some time to pass, between resolving on the action and the action being done unto the patient.

..

.. Concepts are word class

..

Some concepts that are coded as adjectives in English, are coded as verbs in beu. Usually they are body internal processes or states. So joining "to sleep", "to love", "to hate" (which are stative verbs in English) we have concepts like "to be angry", "to be jealous", "to be healthy". Note ... most of these are mental states ... but not all.

Now in beu adjectives become verbs simply by adding the verb train to them. For example ...

joga = wide

joguran komwe = it seems they have widened the road

jogado = to widen

Notice that these derived verbs are all transitive. To have the intransitive sense, you must use the verb "become" along with the adjective.

..

..... Eleven Verbs

..

| cùa | to leave, to depart | cuanau | to stop (transitive) |

| día | to arrive, to reach | dianau | to start (transitive) |

| pòi | to enter, to join | poinau | to put in |

| féu | to exit, to leave | feunau | to take out |

| bwí | to see | bwinau | to show |

| glù | to know | glunau | to tell |

| pyà | to fly | pyanau | to throw |

| jó | to go | jonau | to send |

| tè | to come | tenau | to summon |

| bái | to rise | bainau | to raise |

| kàu | to fall | kaunau | to lower |

cùa and día are transitive verbs and the object slot is usually filled by a location. However the object slot is sometimes filled with a hipe, in which case cùa and día mean "to stop" and "to start" respectively. However if the verb expressed by the hipe is transitive, then cuanau and dianau must be used. (If the subject and the hipe object are different then cuanau and dianau must be used ?)

pyà,jó, tè, bái and kàu are intransitive.

..

... And 7 more

..

slè is an transitive verb meaning "to stay". The object slot is usually filled by a location. However the object slot is sometimes filled with a hipe, in which case slè means "continue".

The verb yái means "to have on your person" or perhaps "to have easy access to" if we are talking about a larger object. For example ...

jonos yór ama = John has an apple

As with all transitive verbs it has a passive form.

jono yawor = John is present

ama yawor hí jono = The apple is on John's person

....

The verb byó means "to possess legally" to "own"

jenes byór wèu = Jane owns a car

And the passive form ...

wéu byowor hí jene = The car is owned by Jane

....

yái is also used to show location.

ʔupaiʔi yór bode = "there are small birds in the tree"

Note ... a copular expression can also be used to express the above ...

....

"There is a God" => God is real

"There is no God" => God is imaginary

....

yái = to have on your person….……. slight obligation => might ???

’’byó’’’ = to possess legally ………………………. obligation/duty => inevitability

’’’dwai’’’l = to reach for ………………………............. try

gwói = to pass ......................... to manage/to succede

blèu = to hold ………………………................... physical ability => sometimes

glù = to know ...............................mentall abiliy

..

..

The transitivity of verbs in béu

All languages have a Verb class, generally with at least several hundred members.

Leaving aside copula clauses, there are two recurrent clause types, transitive and intransitive. Verbs can be classified according to the clause type they may occur in: (a) Intransitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of an intransitive clause; for example, "snore" in English. (b) Transitive verbs, which may only occur in the predicate of a transitive clause; for example, "hit" in English. In some languages, all verbs are either strictly intransitive or strictly transitive. But in others there are ambitransitive (or labile) verbs, which may be used in an intransitive or in a transitive clause. These are of two varieties: (c) Ambitransitives of type S = A. An English example is "knit", as in "SheS knits" and "SheA knits socksO". (d) Ambitransitives of type S = O. An English example is "melt", as in "The butterS melted" and "SheA melted the butterO".

English verbs can be divided into the four types mentioned above. béu verbs however can only be divided into two types, a) Intransitive, and b) Transitive. In this section it will be shown how the four English types of verb map into the two béu types. (Of course there is nothing special or unique about English ... other than the fact that a reader of this grammatical sketch will already be familiar with English)

Intransitive

..

An intransitive verb in English => an intransitive verb in béu

..

An example of an intransitive verb in English is "laugh". This is also an intransitive verb in béu. In a clause containing an intransitive verb, the only argument that you have is the S argument.

By the way ... some concepts that are adjectives in English are primarily intransitive verbs in béu, for example ;- to be angry, to be sick, to be healthy etc. etc.

Ambitransitive of type S=O

..

| x) An intransitive in béu | |

| An "ambitransitive of type S=O" => | y) A pair of verbs, one being intransitive and one being transitive |

| z) A transitive in béu |

..

x) "Ambitransitive verbs of type S=O" which have greater frequency in intransitive clauses, are intransitive verbs in béu.

For example ;- flompe = to trip, (ò)S flomporta = She has tripped

y) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which are frequent in both transitive and intransitive clauses, are represented as a pair of verbs in béu, one of which is intransitive and one transitive. There are a few hundred béu verbs that come in pairs like this. One should not be thought of as derived from the other; each form should be considered equally fundamental. All the pairs have the same form, except the transitive one has an extra "l" before its final consonant.

For example hakori kusoniS = his chair broke : (pás)A halkari kusoniO = I broke his chair :

z) "Ambitransitive of type S=O" verbs which have greater frequency in transitive clauses, are transitive vebs in béu.

For example ;- nava = to open, (pás)A navaru pintoO = I am going to open the door

Ambitransitive verbs of type S=A and Transitive verbs

.

.

| An "ambitransitive of type S=A" | |

| or | => A transitive in béu |

| A transitive verb in English |

. .

I am taking transitive and ambitransitive of type (S=A) together as I consider them to be basically the same thing but tending to opposite ends of a continuum.

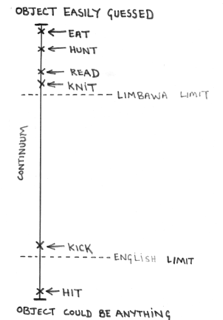

Consider the illustration below.

At the top (with the "objects easily guessed") are verbs that are normally designated "ambitransitive of type S=A".

At the bottom (with the "objects could be anything") are verbs that are normally designated "transitive".

.

.

Considering the top first. One can have "IA eat applesO" or we can have "IS eat"

Then considering the bottom. One can have "IA hit JaneO" but you can not have "*IS hit"

Moving up from the bottom. One can imagine a situation, for example when showing a horse to somebody for the first time when you would say "SheS kicks". While this is possible to say this, it is hardly common.

As we go from the top to the bottom of the continuum;-

a) The semantic area to which the object (or potential object if you will) gets bigger and bigger.

b) At the bottom end the object becomes is more unpedictable and hence more pertinent.

c) As a consequence of a) and b), the object is more likely to be human as you go down the continuum.

béu considers it good style to drop as many arguments as possible. In béu all the verbs along this continuum are considered transitive. Quite often one or both arguments are dropped, but of course are known through context. If the O argument is dropped it could be known because it was the previously declared topic (however more often the A argument is the topic tho', and hence dropped, represented by swe tho' as its case marking can not be dropped), it could be because the verb is from the top end of the continuum and the action is the important thing and the O argument or arguments just not important, or the dropped argument could be interpreted as "something" or "somebody", or it could be a definite thing that can be identified by the discouse that the clause is buried in.

Ambitransitive verbs

fompe is an intransitive and a transitive verb (S and A)

jene fompori = Jane tripped

jonos fompori jene = John tripped Jane

halka is an intransitive and a transitive verb (S and O)

pintu halkori = the door broke

jonos pintu halkori = John broke the door

A list of 6 ambitransitive (S and A) verbs

tonza = to awaken, to wake up

henda = to put on clothes

laudo = to wash

poi = "to enter" or "to put in"

gau = "to rise" or "to raise"

sai = "to descend" or "to lower"

To recognize as a transitive clause you must look for the ergative -s, if no -s then we have an intransitive clause.

Or alternatively you must look for the particle kyebwo

Tom Jerry halkuri = Tom and Jerry broke

Tom Jerry halkuri kyebwo = Tom and Jerry broke one and other.

ké = result, consequence

bò = case, example, instance

hí = source, origin

Now while these words are still used as nouns, they have developed a longer form ... possibly to reduce ambiguity with the particulate usage.

ké => kegozo = result, consequence ... (gozo = fruit)

bò => bozomba = case, example, instance ... (somba = to sit)

hí = => hidito = source, origin ... (dito = point, dot)

..... Word building

..

Many words in béu are constructed from amalgamating two basic words. The constructed word is non-basic semantically ... maybe one of the concepts needed for a particular field of study.

..

In béu when 2 nouns are come together the second noun qualifies the first. For example ...

toili nandau (literally "book" "word") ... the thing being talk about is "book" and "word" is an attribute of "book".

Now the person who first thought of the idea of compiling a list of words along with their meaning would have called this idea toili nandau.

However over the years as the concept toili nandau became more and more common, toili nandau would have morphed into nandəli.

Often when this process happens the resulting construction has a narrower meaning than the original two word phrase.

There are 4 steps in this word building process ...

1) Swap positions : toili nandau => nandau toili

2) Delete syllable : nandau toili => nandau li

3) Vowel becomes schwa : nandau li => nandə li

4) Merge the components : nandə li => nandəli

The above example is for 2 non-monosyllabic words. In the vast majority of constructed words the contributing words are polysyllables.

The process is slightly different when a contributing word is a monosyllabic. First we look at the case when the main word is a monosyllable ...

wé deuta (literally "manner soldier")

1) Swap positions : wé deuta => *deuta wé ........ there is no step 2

3) Vowel becomes schwa : *deuta wé => *deutɘ wé

4) Merge the components : *deutə wé => deutəwe

And the case when the attribute is a monosyllable ...

mepe hí (literally "form origin")

1) Swap positions : *hí mepe

2) Delete syllable : *hí pe .......................................... there is no step 3

4) Merge the components : *hí pe => hipe

And the case when the attribute ends in a consonant ...

megau peugan ... "body of knowledge" "society"

1) Swap positions : *peugan megau

2) Delete syllable : *peugan gau

3) Delete the coda and neutralize the vowel :*peugan gau => *peugə gau

4) Merge the components :*peugən gau => peugəŋgau

And the case when the main word has a double consonant before the end vowel ...

kanfai gozo ... merchant of fruit

1) Swap positions : *gozo kanfai

2) Delete syllable : *gozo fai ............................. Note kan is deletes, not just ka

3) Vowel before the final consonant becomes schwa :*gozo fai => *gozə fai

4) Merge the components :*gozə fai => gozəvai

There are no cases where both contributing words are monosyllables.

Note ...

1) the schwa is represented by a sturdy dot.

2) the consonant before the schwa takes its final form

3) the consonant after the schwa takes its medial form

When spelling words out, this dot is pronounced as jía ... meaning "link".

Notice that when you hear nandəli, deutəwe or peugəgau you know that they are a non-basic words (because of the schwa).

Also when you see nandəli or deutəwe, peugəgau written you know that they are non-basic words (because of the dot).

However when you come across hipe it is not immediately obvious that it's a non-basic word.

This method of word building is only used for nouns.

..

..... And Or

..

In the last chapter we said that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilana endstuck. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilana then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

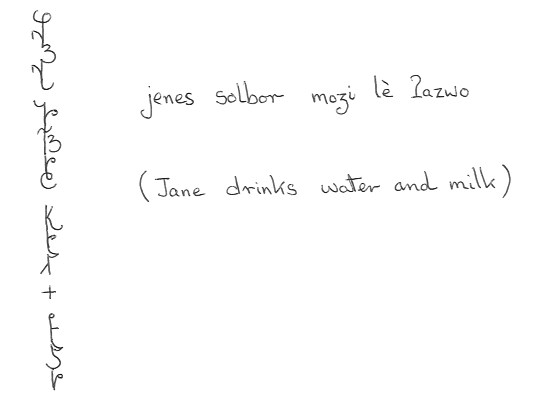

jonos jenes solber moʒi = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of endstuck pilana, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lè is placed between them.

This is one of these words that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

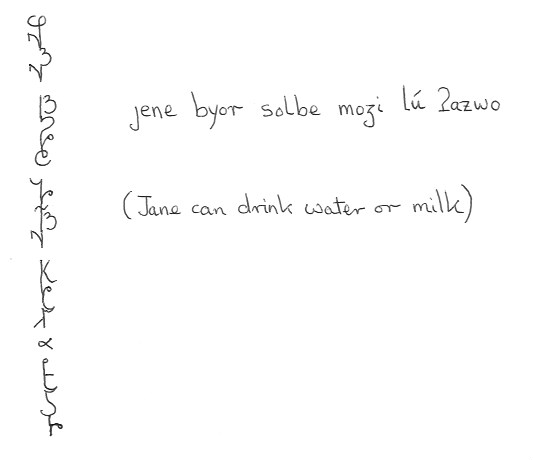

Another similar particle is lú meaning "or". Its also has a special symbol. See below ...

jene byor solbe moʒi lú ʔazwo = "Jane can drink water or milk" .... is it jene or jenes ???

jonos jenes kuri auva sadu lè aiba ʔusʔa faja dí = John and Jane have seen two elephants and three giraffes this morning. ???

In béu as in English If it is obvious to the listener that a string of nouns are going to be given then they can be annunciated with just a slight pause between them. However lè must always separate the last from the second last. But having lè between every member of a list is also permissible.

..

..... Bicycles, Insects and Spiders

..

wèu = vehicle, wagon

weuvia = a bicycle

weubia = a tricycle

Perhaps can be thought of derived from an expression something like "wagon two-wheels-having" or "wagon double-wheel-having" with a lot of erosion.

Notice that the "item" that is numbered (i.e. wheel) is completely dropped ... probably not something that would evolve naturally.

There are not many words in this category.

joduʒia* = spider

jodulia = insect

jodugia = quadraped

joduvia = biped

nodebia = a three-way intersection ... usually referring to road intersections.

nodegia = a four-way intersection

nodedia = a five-way intersection

nodelia = a six-way intersection ... and you can continue up of course.

*jodu = animal ... from jode = to move

..

..... Ambitransitive verbs

..

In English there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes involve two participants. For example "knit" or "turn". In English you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up after the verb (that is ... an O argument has turned up) ... S and A appear the same in English.

Similarly in béu there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes take two participants. For example mekeu "knit" or kwèu "turn". In béu you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up with the ergative marker -s attached (that is ... an A argument has turned up) ... S and O appear the same in béu.

Note on nomenclature

Dixon calls "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitive verb of type S=A or an [S=A ambitransitive verb].

I call "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one unaffected argument" or an [unaffected ambitransitive verb].

For "knit" the preverb argument* is either S or A .... For mekeu the unaffected argument is either S or A.

Dixon calls "turn"/kwèu is an ambitransitive verb of the type S=O or an [S=O ambitransitive verb].

I call "turn"/kwèu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one affected argument" or an [affected ambitransitive verb].

For "turn" the affected argument is either S or O .... For kwèu the naked argument** (i.e. no -s) is either S or O.

*It is also the unaffected argument.

**It is also the affected argument.

..

..... More on definiteness

..

In the section on word order we said that when the person being spoken to can identify X as one particular X ... then X will come before the verb, where X is any of the A O or S arguments.

However ... the above leaves undefined, whether the person speaking can identify X. This can be made explicit in béu by adding either the particle é or the participle fawai. For example ...

doikora bàu = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known-ness to the person speaking is not defined.

doikora é bàu = Some man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : unknown to the person speaking.

doikora bàu fawai = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known to the person speaking.

This distinction is also made in certain natural languages. For example with nouns in Samoan ...

o sa fafine = a woman

o le fafine = a woman ……. unknown to you but known to me

Or between these two indefinite pronouns in Latin ...

aliquis = somebody

quidam = somebody ……. unknown to you but known to me

[ Note ... the argument qualified by é or fawai invariably come after the verb. Also, while it is possible to imagine some scenario where an argument is known to the person being spoken to but unknown to the person speaking, in reality this very very rarely happens and I know of no natural language that makes this distinction. ]

..

One interesting point .....

Take the sentence ... "She wants to marry a Norwegian"

How do we show the definiteness of the Norwegian in relation to the subject. That is ... does she have a certain Norwegian in mind or does she want to marry any Norwegian.

In English ... when you hear this sentence ... you will nearly always know from the context, which of the two meanings is meant.

"any" or "that she knows" could be added to make the distinction explicit within the sentence itself.

..

..... Polar question and focus

..

A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

To turn a normal statement into a polar question the particle ʔai is put at the very end.

Now this is the only single syllable word that can not be said to be low tone or high tone (well I suppose there are the short verbs found in the verb chains as well).

It starts of neutral tone and rises. In fact if you look in chapter 1 and look at the intonation profiles of the interjections, you will see how ʔaiwa is pronounced. ʔai is pronounced exactly as the first part of ʔaiwa. In beu orthography, this word is given its own symbol ... a double spiral. I will write it as ʔai? ... why not.

ʔai is neutral as to the response you are expecting.

To answer a positive question you answer ʔaiwa "yes" or aiya "no". For example ...

glá è hauʔe ʔái = Is the woman beautiful ? .......... If she is beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she isn't answer aiya.

To answer a negative question you can not use ʔaiwa or aiya but must repeat the whole sentence in either the negative or the positive.

glá sorke hauʔe ʔái = Isn't the woman beautiful ? .... If she is beautiful, answer glá è hauʔe, if she is not answer glá sorke hauʔe

Sometimes it is permissible to drop everything except the verb (which of course incorporates the negative element).

To bring a word into focus you put cù in front of it. For example ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement ... bàus cù glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers. (English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to a word).

Statement ... bàus ná glá hauʔe nori alha = the man gave flowers to the beautiful woman

Focused statement ... bàus ná cù glá hauʔe nori alha = It is to the beautiful woman that the man gave flowers to.

Any argument can be focused in this way. In fact the verb can also be focused using this method.

To question one element in a clause, you have cù in front of the element and ʔái sentence final.

Alternatively you can dispense with the cù and put the ʔái directly behind the element you want to question. For example ...

cù bàus glán nori alha ʔái = Is it the man that has given flowers to the woman ?

bàus ʔái glán nori alha = Is it the man that has given flowers to the woman ?

[ should I replace cù with á]

..

..... Content questions

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 7 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

béu has 7 content question words also ...

..

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| láu | "how much" or "how many" |

| nái | which |

..

nós and mís are the ergative equivalents to nén and mín (the unmarked words)

There is a strong tendency for nén nós mín and mís to be sentence-initial.

There is a tendency for the NP's containing kái, láu and nái to be sentence-initial.

kái and nái come after the nouns they ask about.

láu comes before the noun it asks about. ??? [ this doesn't agree with what I wrote in fandaunyo Chapter 2 ... but maybe láu in number slot : kái in adjective slot and nái in determiner slot }

"when" is represented by kyù nái (which occasion) ... "where" by dá nái (which place)

"how" is represented by wé nái (which way) ... "why" by nenji (for what)

The pilana are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.

Here are some example ...

Statement ... báus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 ... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 ... minon bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 ... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... ná glá nái bàus nori alha = the man gave the flowers to which woman ?

Question 5 ... só bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 6 ... alha kái báus glán nori = what type of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 7 ... láu alha báus glán nori = how many flowers did the man give the woman

..

Note ... In English as in about 1/3 of the languages of the world it is necessary to front the content question word.

..

.. Specifiers X determiners

..

Below is a table showing all the specifiers plus a countable noun plus the proximal determiner "this".

..

| 1 | ù báu dí | all of these men OR all these men |

| 2 | hài báu dí | many of these men |

| 3 | iyo báu dí | few of these men OR a few of these men |

| 4 | auva báu dí | two of these men => ataitauta báu dí ... 1727 of these men |

| 5 | jù báu dí | none of these men |

| 6 | í báu dí | any of these men OR any one of these men |

| 7 | é báu dí | one of these men |

| - 8 - | éu báu dí | some of these men |

| 9 | ?? báu dí | every one of these men |

| 10 | nò báu dí | several of these men OR several of these men here |

| 11 | é nò báu dí | one or more of these men ??? |

| 12 | í auva báu dí ... | any 2 of these men => í ataitauta báu dí ... any 1727 of these men |

..

The above table is worth discussing ... for what it tells us about English as much as anything else.

..

One line 1 ... I do not know why "all these men" is acceptable ... on every other line "of" is needed (to think about)

Similarly on line 3 ... I do not know why "a few" is a valid alternative.

Notice that *aja báu dí does not exist. It is illegal. "one of these men" is expressed on line 7. aja only used in counting ???

I should think more on the semantic difference between line 10 and line 8. ???

line 1 and line 9 are interesting. Every language has a word corresponding to "every" (or "each", same same) and a word corresponding to "all". Especially when the NP is S or A, "all" emphasises the unity of the action, while "every" emphasises the separateness of the actions. Now of course (maybe in most cases) this dichotomy is not needed. It seems to me, that in that case, English uses "every" as the default case (the Scandinavian languages use "all" as the default ??? ). In béu the default is "all" ù.

On line 9, it seems that "one" adds emphasis to the "every". Probably, not so long ago, "every" was valid by itself. The meaning of this word (in English anyway) seems particularly prone to picking up other elements (for the sake of emphasis) with a corresponding lost of power for the basic word when it occurs alone. (From Etymonline EVERY = early 13c., contraction of Old English æfre ælc "each of a group," literally "ever each" (Chaucer's everich), from each with ever added for emphasis. The word still is felt to want emphasis; as in Modern English every last ..., every single ..., etc.)

..

This table is also valid for the distal determiner "that". For the third determiner ("which") the table is much truncated ...

..

| 1 | nò báu nái | which men |

| 2 | ... auva báu nái | which two men => ataitauta báu nái which 1727 of these men |

..

Below I have reproduced the above two tables for when the noun is dropped (but understood as background information). It is quite trivial to generate the below tables. Apart from lines 8 and 10, just delete "men" from the English phrase and báu from the béu phrase. (I must think about why 8 and 10 are different ???)

..

| 1 | ù dí | all of these OR all these |

| 2 | uwe dí | many of these |

| 3 | iyo dí | few of these OR a few of these |

| 4 | auva dí | 2 of these => ataitauta dí ... 1727 of these |

| 5 | kyà dí | none of these |

| 6 | í dí | any of these OR any one of these |

| 7 | é dí | one of these |

| - 8 - | è dí | some of these OR several of these |

| 9 | yú dí | every one of these |

| 10 | nò dí | these NOT several of these |

| 11 | é nò dí | one or more of these |

| 12 | í auva dí ... | any 2 of these => í ataitauta dí ... any 1727 of these |

..

| 1 | nò nái | which ones |

| 2 | ... auva nái | which two => ataitauta nái which 1727 |

..

In the last section we introduced the rule, that when a determiner is the head, then the determiner changes form (an a is prefixed to it)

Now we must introduce an exception to that rule ... when you have a specifier just to the left of a determiner (in this conjunction, the determiner MUST be the head) the determiner takes its original form.

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences