Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb: Difference between revisions

| Line 318: | Line 318: | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''jó''' = to go | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

| Line 331: | Line 331: | ||

|align=center| '''byó''' = to own | |align=center| '''byó''' = to own | ||

|align=center| '''blèu''' = to hold | |align=center| '''blèu''' = to hold | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''bwí''' = to see | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| '''gàu''' = to do | |align=center| '''gàu''' = to do | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''glù''' = to know | ||

|align=center| '''gwói''' = to pass | |align=center| '''gwói''' = to pass | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 355: | Line 355: | ||

|align=center| '''sàu''' = to be | |align=center| '''sàu''' = to be | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

|align=center| '''slè''' = to | |align=center| '''slè''' = to stay | ||

|align=center| '''swé''' = to speak, to say | |align=center| '''swé''' = to speak, to say | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| '''kaù''' = to fall | ||

|align=center| '''kyò''' = to use | |align=center| '''kyò''' = to use | ||

|align=center| '''klói''' = to think | |align=center| '''klói''' = to think | ||

| Line 373: | Line 373: | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| '''wàu''' = to | |align=center| '''wàu''' = to store | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| | ||

Revision as of 18:46, 16 December 2015

..... The verb forms

.. The infinitive

..

A verb in its infinitive form is called nandau hipe

About 32% of multi syllable verbs end in "a".

About 16% of multi syllable verbs end in "e", and the same for "o".

About 9% of multi syllable verbs end in "au", and the same for "oi", "eu" and "ai".

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk .... not to walk

hipe = ( NP) nandau hipe (NP) (other verbal adjuncts) ... a hipe with any of these elements is a hipe kaza

A nandau hipe can also be called hipe baga

Where the RHS NP is the O argument and the LHS NP is the A argument.

A hipe can be an argument in a clause ... just as a fandau can. For example ...

The kitten playing with the string and the monkey eating the cake were very amusing. ???

(a noun would have the determiner "this", a hipe has the determiner "thus" wedi(if you demonstrate the action)or wede (if someone else demonstrates the action))

???

..

.. The indicative

..

The indicative is the most complicated verb form by far.

The indicative is called the hukəpe

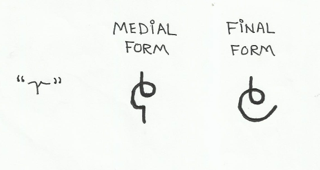

But first we must introduce a new letter.

..

..

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such.

If you hear "r", you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

This "r" and the suffixes attached to it, are what is known as the verb-train (translated from beu)

One quirk of the beu orthography is that all instances of "o" in the verb train are dropped. A quirk of the ORTHOGRAPHY, not the phonology, so remember to pronounce these "o"s.

..

.... Agent

..

The first piece of information that must be given in the indicative is who does the action. To do this you first ...

1) Deleted the final vowel from the infinitive.

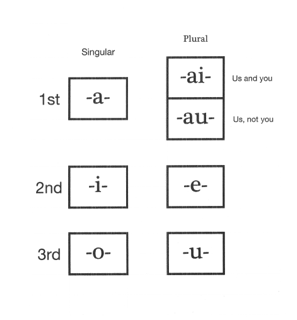

2) Then one of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer..

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikair and doikaur = we walk

doikir = you walk

doiker = you walk

doikr = he/she/it walks ... ( pronounced DOIKOR )

doikur = they walk

..

... Tense/aspect

..

The bare "r" is for timeless statements, also tends to be used for habitual statements, especially when an adverb of time is mentioned. We can call this the "aortist".

1) doikar = I walk

For the past tense you add "i" after the "r".

2) doikari = I walked

For the future tense you add "u" after the "r".

3) doikaru = I will walk

For the present tense you use the copula and a participle.

4) sar doikala = I am walking

And of course by tensing the copula you can make the following.

5) sari doikala = I was walking

6) saru doikala = I will be walking

For the perfect you add "a" after the "r".

7) doikara = I have walked

And for the pluperfect you add "ai" after the "r".

8) doikarai = I had walked

And for the future perfect you add "au" after the "r".

9) doikarau = I will have walked

So there we are ... we have 9 tense/aspect distinctions in all.

..

.. Negation

..

To negate any of the above, you add a "j" before the tense/aspect vowel and after the indicative "r".

For the aortist, the negative is formed by adding "jo". For example ...

doikarj = I do not walk ... ( pronounced DOIKARJO )

?????????????????

"not yet" is translated by the word jindin after the negated verb. Or jindin can be used by itself in answer to a question. "already" can be translated by the word duˋ after the verb. Or duˋ can be used by itself in answer to a "yes/no" question given using the perfect.

?????????????????

..

.. Evidence

..

There are three markers that cites on what evidence the speaker is saying what he is saying. You do not have to stipulate on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. Most occurrences of the indicative verb do not have an evidence marker.

The markers are as follows ...

a) doikrin = "I guess that he walked" ... That is, worked out from some clues.

b) doikris = "They say he walked" ....... That is you have been told by some third party.

c) doikria = "he walked, I saw him"

Note that the eye witness evidential only works with the past tense.

For the aortist, the evidence affixes are "on" and "os".

doikrn = I guess that he walks ( pronounced DOIKORON )

doikrjs = They say she does not walk ( pronounced DOIKORJOS

..

.. The subjunctive

..

The subjunctive verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "s".

The subjunctive is called the sudəpe

The main thing about the subjunctive is that it is not "asserted" ... it is not insisted upon ... there is a shadow of doubt as to whether the action will actually take place.

This is in contrast to the indicative mood. In the indicative mood things definitely happen.

There are three places where the subjunctive turns up.

1) There are a set of leading verbs that always change there trailing verbs to the subjunctive. For example, the leading verbs "want", "wish", "prefer", "request/ask for", "suggest", "recommend", "love/like", "think/judge", "be afraid", "demand/command", "let/allow", "advise", "forbid" etc etc. Often with the above there is a particle ta immediately after the leading verb. However taˋ can be dropped sometimes.

2) After haˋ "if". For example haˋ doikos, doikas = If he walks, I will walk

Note the gap between the two parts of the sentence.

The above can be reconfigured a bit ... doikaru haˋ doikos = I will walk if he walks

Note that the first verb is in indicative form. Also no gap is needed (although you can put one in if you want)

"if only I could walk" ... the exact same construction is used in beu for wishful thinking.

3) As part of stand alone clauses ...

doikas = "should I walk" or "let me walk" or "how about me walking" or "can I walk" or "maybe I should walk"

There is never any need for the question particle ʔai? ... even though some of my translations are questions in English.

doikis = "maybe you should walk" or "why don't you walk" or "how about you walking"

doikos = "let him walk"

doikos jono = "let John walk"

For transitive verbs ...

timpos baus waulo = let the man hit the dog

SAVE GOD KING ????????? = God save the king

TAKE DEVIL HIM ???????? = May the Devil take him

Note that for the subjunctive in a stand alone clause there is a fixed word order ... V S or V A O .

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding ka. For example ...

doikoska = best not to let him walk

It is a convention in beu that the "a" is always dropped. I will follow that convention in my transliteration. So ... doikosk from now on.

They locked him up so that he would starve to death

They let him out at night so that he would not starve to death

..

.. The imperative

..

This is used for giving orders. When you utter an imperative you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action (although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible).

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

1) First the final vowel of the infinitive is deleted and replaced with u.

doika = to walk

doiku = walk !

For monosyllabic verbs u is prefixed.

dó = to do

udo = do it !

The negative imperative is formed by putting the particle kyà before the infinitive.

kyà doika = Don't walk !

..

..... Short verbs

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an indicative, subjunctive or imperative verb form is to delete the final vowel from the infinitive. However this is only applicable for multi-syllabe words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different.

For a monosyllabic verbs the indicative endings and subjunctive suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive. For example ...

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ... swo.uske = lest they fear ...... etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ... etc. etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ... etc. etc.

dàu = to arrive

cái = to depart

..

The above is the general rules for short verbs, however the 37 short verbs below the rules are different.

Their vowels of the infinitive are completely deleted for the indicative and subjunctive verb forms. For example ...

myàr gì = I love you ........................ not * mye.ar gì

pòr nambo = he enters the house ... not *poi.or nambo

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to like, to love | ||

| yái = to have | |||

| jó = to go | jwèu = to undergo, to bear, to endure, to stand | ||

| feuˊ = to exit | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

| bái = to rise | byó = to own | blèu = to hold | bwí = to see |

| gàu = to do | glù = to know | gwói = to pass | |

| dià = to arrive, to reach | dwài = to reach for | ||

| lái = to change | |||

| cuà = to leave, to depart | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slè = to stay | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kaù = to fall | kyò = to use | klói = to think | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyá = to fly | plèu = to follow | |

| tè = to come | |||

| wàu = to store | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to put |

The imperative prefix is -u for all* short verbs. For example ...

unyau nambo = go home !

uzwo = fear !

ugai = be in pain !

uʔau ʃì = take it !

.* All short verbs apart from one that is. joh "to go" has the imperative form ojo.

Some nouns related to the above ... yaivan = possessions, property, flovan = food, dovan = products, nauvan = tax, tribute, glavan = reserves, dó = things that must be done, dwái = deeds, acts, actions, behaviour.

A particle related to the above ... yoˊ ... a particle that indicates possession, occurs after the "possessed" and before the "possessor.

..

..... Combining clauses

..

Grammar provides ways to make the stream of words coming out a speaker's mouth nice and smooth ... no lumpy bits. Well the smoothness comes from the rules (you can think of the rules as traffic rules, and affixes and particles as the traffic signs), and getting rid of the lumps entails dropping the elements that are already known, that are already accessible in the mind of the hearer. This section is about getting rid of these elements : both arguments and person-tense markers.

..

Now we have already come across the particle lé which links nouns together. béu doesn't use the same particle for linking clauses together though. It uses the particle è. English allows the dropping of an S or A argument in a sentence when this argument has already been established as the topic. béu is exactly the same : it allows the dropping of an S or A argument. However when you have a clause with the S argument dropped, this clause is not introduced by è, it is introduced by the particle sé. For example ...

A) bawa dwuri = The men came

B) bawas kuri gala = The men saw some women

C) bawa dwuri sé kuri gala = The men came and saw some women.

D) bawas kuri gala è dwuri = The men saw some women and then came.

You can see that C) flows a lot better than A) juxtaposed with B). And D) flows a lot better than B) juxtaposed with A).

béu has a technique that integrates two clauses even further. I call it the "verb chain". Let me demonstrate. Let's first translate ... "Yesterday John caught three fish."

yesterday = jana

to catch = holda

three = léu

a fish = fizai

So ... "Yesterday John caught three fish" = jana jonos holdri léu fizai

OK simple enough. Now how about "Yesterday John caught three fish, and then cooked and ate them"

In béu it is considered unnecessary to include person-tense information for "to cook" and "to eat". Well it is the same agents through-out and the tense is quite easy to deduce from the logic of the situation. So slanje (to cook) takes a special form that is only used in verb chains. The final vowel is changed to i. All multi syllable verbs take this transformation. Also all single syllable verbs change there final vowel to a schwa and loose their tone. Hence flò (to eat) becomes flə. So ...

1) "Yesterday John caught three fish, and then cooked and ate them" = jana jonos holdri léu fizai, slanji, flə

The above is an example of a verb chain.

The above three actions are deemed to be separated by some time period (however short), hence there are two short pauses (which I show by using comas)

Let us look at another example. OK how about "All afternoon I was writing reports and answering the telephone"

afternoon = falaja

to write = kludau

report(noun) = fyakas

telephone(noun) = sweno

to answer = nyauze

2) "All afternoon I was writing reports and answering the telephone" = falaja uˊ kludar fyakas sweno nyauʒi

Unlike example 1), here the actions are interspersed randomly throughout the afternoon. There is considered no time between the actions, indeed they could possibly overlap, hence no pauses in 2)

It would also be possible to render the above as falaja u sweno nyauzar kludi fyakas ... means the same thing.

Notice that in 2) we have two verb-object-pairs, (kludau, fyakas) and (sweno, nyauze). While an object must stay next to its verb, there is a tendency for it to precede the verb when it is definite and to follow it when indefinite).

Let us do another example. Let us translate "John walked along the road whistling"

to whistle = wiʒia

to walk = doika

to follow = plèu

road = komwe

3) John walked along the road whistling = jono doikri komwe plə wiʒi

Unlike examples 1)and 2), here all the actions are considered simultaneous.

Note that in the English sentence above, one of the verbs is made into a participle, (whistling) and one represented by a preposition (along).

We can also express 3) as jonos komwe plri doiki wiʒi or jono wizri doiki komwe plə .

Note that "John" is in his ergative form when the verb marked with the person-tense is transitive. The marked verb MUST be the first one.

Also note that in example 1) "John" is in his ergative form. This is because the verb that takes the person-tense marker is a transitive verb. In 2) "John" is in his base form.

Let us do one last example ... "The women were catching, cooking and eating fish all afternoon"

4)falaja u galas holdur fizaia slanji flə

Because there are no pauses we would consider that the three processes were simultaneous (or at least that the "catching" overlapped with the "cooking" and the "cooking" overlapped with the "eating".

So it can be seen that the verb chain can give some idea as to its internal time structure. However it can not always give an accurate time structure in every situation and sometimes you must fall back to conjoining clauses (with conjunctions of course).

This seems a good place to list all the particles that can join clauses.

sé/è : these have nothing to say about the relative timing of clause A (before the particle) and clause B (after the particle).

sé dù/è dù : these mean that action B follows on immediately from action A.

sé kyude/è kyude : these mean that action B follows action A but not necessarily immediate. Sometimes sé è are dropped.

ʔesku : this means that action A and B happen at the same time. Usually we have different actors in the two clauses, but not always.

Another particle used for combining clauses is tè. This is exactly equivalent to the English "but". tè is occasionally also used before nouns. However before nouns it is more usual to use ???

There are also some phrases with more "sound.weight" that have the exact same meaning as tè.

..

..... Verb chains

I whistled while I walked = wizari doikala ...because doikala is an adjective, if placed directly after a verb, it acts like an adverb.

When 2 (or more) actions are considered inextricably tangled up in each other, béu forms a verb chain.

In a verb chain, usually the "most surprising" (i.e. the verb that conveys the most information) comes first and takes the normal ending (i.e. infinitive, indicative, subjunctive or imperative).

.............. He is lowering John down the cliff-face to the ledge => ós gora jono cliff gìa ledgeye ??

I dragged the dog along the road ??

joske pòi nambo = let's not let him go into the house ... there are 2 verbs in this chain ... jòi and pòi

jaŋkora bwá nambo dwía = he is running out the house (towards us) ... there are 3 verbs in this chain ... jaŋka, bwá and dwé

doikaya gàu pòi nambo jìa = Walk (command) down into the house (we are in the house) ... there are 4 verbs in this chain ... doika, gàu, pòi and jòi

Extensive use is made of serial verb constructions (SVC's). You can spot a SVC when you have a verb immediately followed (i.e. no pause and no particle) by another verb. Usually a SVC has two verbs but occasionally you will come across one with three verbs.

*Well maybe not always. For example jompa gàu means "rub down" or "erode". Now this can be a transitive verb or an intransitive verb. For example ...

1) The river erodes the stone

2) The stone erodes

With the transitive situation, the "river" is in no way going down, it is the stone. Cases where one of the verbs in a verb chain can have a different subject are limited to verbs such as erode (at least I think that now ??). Also the verbal noun for jompa gàu is not formed in the usual way for word building. Erosion = gaujompa

gaujompa or gajompa a verb in its own right ... I suppose that this would happen given time ??

I work as a translator ??? ... I work sàu translator ??

"want" ... "intend" ... etc. etc. are never part of verb chains ?? ..........................................

........... Unbalanced

..

Now all the above were examples of "one off" or "balanced" verb chains ( "balanced" in the sense that all the verbs have about the same likelihood ). A more common type of verb chain is one in which some common verb is appended to a clause to give some extra information. Examples of these verbs are ... "enter", "exit", "cross", "follow", "to go through", "come", "go", etc. etc. etc.

................. enter and exit

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the main verb. They are used where "into" and "out of" are used in English.

pòi = to enter

bwá = to exit

nambo bwá dwé = to come out of the house

nambo pòi jòi = to go into the house

nambo pòi dwé = to come into the house

nambo bwá jòi = to go out of the house

bwá nambo dwía = to come out of a house

pòi nambo jìa = to go into a house

pòi nambo dwía = to come into a house

bwá nambo jìa = to go out of a house

nambo bwá jaŋka dwé = to run out the house (towards us)

bwá nambo jaŋki dwía = to run out a house (towards us)

..

............... across & along & through

..

When in verb chains, these 3 verbs tend to be the main verb.

kwèu = to cross, to go/come over

plèu = to follow, to go/come along

cwá = to go/come through

komwe kwèu = to cross the road

komwe kwèu doika = to walk across the road

kwèu komwe doiki = to walk across a road

kwèu komwe doiki dwía = to walk across a road (towards the speaker)

plèw and cwá follow the same pattern

Note ... some postpositions

komwe kwai = across the road = across a road

pintu cwai = through the door = along a road

Above are 2 postpositions ... derived from the participles kwewai and cwawai

komwe plewai = along the road

..

............ come and go

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the auxiliary verb.

Obviously they often occur as simple verbs.

"come", "go", "up" and "down" are often stuck on to the end of an utterance ... like a sort of afterthought. They give the utterance a bit more clarity ... a bit more resolution.

The below is nothing to do with verb chains, just a bit to do with the usage of dwé and jòi.

..

HERE------------>--------LONDON

londonye jòi = to go to London ... however if the destination immediately follows jòi -ye is dropped*. So ...

SIMILAR TO ADVERBS + GIVE ... LIGHT GREEN HI-LIGHT

jòi london = to go to London

jòi twè jono = to go to meet John

* In contradistinction, when a origin comes immediately after the verb dwé "to come" the pilana -fi is never dropped.

..

HERE----------<---------LONDON

dwé londonfi = to come from London

dwé jonovi = to come from John

..

.............. ascend and descend

..

When in verb chains, these 2 verbs tend to be the auxiliary verb. They are used where "up" and "down" are used in English.

bía = to ascend

gùa = to descend

CLIMB ʔupai gìa = to climb down a tree

ʔupai CLIMB gìa = to climb down the tree

CLIMB ʔupai bía = to climb up a tree

THROW toili gìa = to throw down a book

These are also often inserted in verb chains to give extra information. The usually precede "come" and "go" when "come" and "go" are auxiliary verbs in the chain.

jòi gàu pòi nambo = to go down into the house

jaŋkora gàu pòi nambo jìa = he is running down into the house (away from us)

jaŋkora pòi nambo gìa dwía = he is running down into the house (towards us)

The two above sentences could describe the exact same event. However there is some slight connotation in the latter that the descending happened at the same time as the entering (i.e. the entrance of the house was sloping ... somewhat unusual)

..

.............. here and there

..

awata = to wonder

jaŋka awata = to run around

..

............. bring and take

..

kli.o = a knife

kli.o ʔáu jòi = to take the knife away

kli.o ʔáu dwé = to bring the knife

ʔáu kli.o jìa = to take a knife away

kli.o ʔauya jòi náu jono = take the knife and go give to John

kli.o ʔauya dwé náu jono = bring the knife and give to John

If however the knife was already in the 2nd person's hand, you would say ...

dweya náu jono kli.o = come and give john the knife ... or ...

dweya náu kli.o jonoye = come and give the knife to john

Note ... the rules governing the 3 participants in a "giving", are exactly the same as English. Even to the fact that if you drop the participant you must include jowe which means away. For example ...

nari klogau tí jowe = I gave my shoes away.

Note ... In arithmetic ʔaujoi mean "to subtract" or "subtraction" : ledo means "to add" or "addition".

Note ... when somebody gives something "to themselves", tiye = must always be used, no matter its position.

..

....... for and against

..

HELP = to help, assist, support

gompa = to hinder, to be against, to oppose

FIGHT = to fight

FIGHT jonotu = to fight with john ......... john is present and fighting

FIGHT HELP jono = to fight for John ... john is present but maybe not fighting

FIGHT jonoji = to fight for John ...........probably john not fighting and not present

FIGHT gompa jono = to fight against John

..

.......... to change

..

lái = to change

kwèu = to turn

lái sàu = to change into, to become

kwèu sàu = to turn into

The above 2 mean exactly the same

Note ...

paintori pintu nelau = he has painted a blue door

paintori pintu ʃìa nelau = he has painted a door blue

..

??? How does this mesh in with clauses starting with "want", "intend", "plan" etc. etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK BY DIXON ??

??? How does this mesh in with the concepts ...

"start", "stop", "to bodge", "to no affect", "scatter", "hurry", "to do accidentally" etc.etc. ... SEE THAT BOOK ON DYIRBAL BY DIXON

..

..... The copula

..

The three components of a copular clause have a strict order. The same order as English in fact. Also the copula subject is always unmarked.

The copula is sàu.

The indicative mood is derived from the infinitive in the usual method. So ...

sàr = I am

sàir = we are

sàur = we are

ʃìr = you are

sèr = you are

sòr = he/she/it is

sùr = they are

One thing is of note ... sòr and sùr are usually shortened to simply r, and appended directly to the copula subject. For example ...

jono r jini tè tomo r tumu = John is clever but Thomas is stupid.

wìa r wikai tè nù r yubau = We are weak but they are strong

If the copular subject ends in a consonant, then sòr and sùr are shortened to or and ur. Note that they lose their tones as they are phonologically part of the last word of the subject NP. That is they are an enclitic.

The only time this shortening does not happen is ahter the relativizer hu.

The rest of the verb train is built up as per usual, except for one thing. k is the negating affix instead of j. In the aortist tense ke is the negating affix instead of jo. For example ...

sorke = he/she is not

Also e is the epenthetic vowel (instead of o) when you want to append an evidential marker to the aortist tense. The e in ke and the epenthetic e are never written in the beu orthography. I will follow that tradition when I am rendering beu in the latin alphabet.

??????????

There are 2 more words that might be considered copula ...

1) twài = to be located, to be placed .... perhaps an eroded form of a participle of tèu "to place"

2) yór = to exist ... a third person indicative form of the verb yái "to have". The third person indicative meaning is completely bleached in this usage.

???????????

..

..... The time of the day

kòi = sun, day (24 hours)

The béu day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called cuaju

The time of day is counted from cuaju. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called ajai (normally just called ajai, but cúa ajai or ajai yanfa might also be heard sometimes).

| 6 o'clock in the morning | cuaju |

| 8 o'clock in the morning | ajai |

| 10 o'clock in the morning | ufai |

| midday | ibai |

| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | agai |

| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | idai |

| 6 o'clock in the evening | ulai |

| 8 o'clock in the evening | icai |

| 10 o'clock at night | ezai |

| midnight | okai |

| 2 o'clock in the morning | apai |

| 4 o'clock in the morning | atai |

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon.

16:00 would be idai : 16:10 would be idaijau : 16:20 would be idaifau .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be idaitau

Now all these names have in common the element idai, hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called idaia (the plural of idai). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties".

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called cuajua. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time ajai was called ajaia(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time cuaju should be called cuajua. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial cuaju. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be cuaju ajau, "twenty past six" would be cuaju afau and so on.

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened idaia.pi

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them apaiʔe.

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued nàn ufau, for 2 hours : nàn ajai (nàn means "a long time")

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In béu they only have the yanfa. The yanfa is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as yanfa also.

..

..... Ordinal numbers & fractions

..

To get an fractional number (regarded as specifiers ... as all numbers are) you just attach s- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| a unit | saja |

| a half | sauva |

| a third | saiba |

| a quarter | sida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

These are fully numbers. They are written in the same way as numbers, except the have a squiggle above them. The squiggle looks like an "8" on its side that hasn't fully closed.

..

To get an ordinal number (regarded as adjectives) you just attach n- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| first | naja |

| second | nauva |

| third | naiba |

| fourth | nida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of nò plus the number.

These forms are adjectives 100% and are always written out in full.

..

To get (I don't know what these are called) (regarded as a noun) you just attach b- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| alone, single | baja |

| a double, a twosome, a duality | bauva |

| a threesome, a trinity | baiba |

| a foursome, a quartet | bida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

Note bajai = lonely

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences