Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 457: | Line 457: | ||

??????????? | ??????????? | ||

.. | |||

== ..... The time of the day== | |||

'''kòi''' = sun, day (24 hours) | |||

The '''béu''' day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called '''cuaju''' | |||

The time of day is counted from '''cuaju'''. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called '''ajai''' (normally just called '''ajai''', but '''cúa ajai''' or '''ajai yanfa''' might also be heard sometimes). | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| 6 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''cuaju''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 8 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''ajai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 10 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''ufai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| midday | |||

|align=center| '''ibai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | |||

|align=center| '''agai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | |||

|align=center| '''idai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 6 o'clock in the evening | |||

|align=center| '''ulai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 8 o'clock in the evening | |||

|align=center| '''icai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 10 o'clock at night | |||

|align=center| '''ezai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| midnight | |||

|align=center| '''okai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''apai''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 4 o'clock in the morning | |||

|align=center| '''atai''' | |||

|} | |||

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon. | |||

16:00 would be '''idai''' : 16:10 would be '''idaijau''' : 16:20 would be '''idaifau''' .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be '''idaitau | |||

Now all these names have in common the element '''idai''', hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called '''idaia''' (the plural of '''idai'''). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties". | |||

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called '''cuajua'''. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time '''ajai''' was called '''ajaia'''(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time '''cuaju''' should be called '''cuajua'''. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial '''cuaju'''. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be '''cuaju ajau''', "twenty past six" would be '''cuaju afau''' and so on. | |||

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened '''idaia.pi''' | |||

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them '''apaiʔe'''. | |||

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued '''nàn ufau''', for 2 hours : '''nàn ajai''' ('''nàn''' means "a long time") | |||

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In '''béu''' they only have the '''yanfa'''. The '''yanfa''' is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as '''yanfa''' also. | |||

.. | .. | ||

| Line 544: | Line 609: | ||

Note '''bajai''' = lonely | Note '''bajai''' = lonely | ||

.. | .. | ||

Revision as of 22:33, 4 December 2015

..... The verb forms

.. The infinitive

..

A verb in its infinitive form is called nandau hipe

About 32% of multi syllable verbs end in "a".

About 16% of multi syllable verbs end in "e", and the same for "o".

About 9% of multi syllable verbs end in "au", and the same for "oi", "eu" and "ai".

To form a negative infinitive the word jù is placed immediately in front of the verb. For example ...

doika = to walk

jù doika = to not walk .... not to walk

hipe = ( NP) nandau hipe (NP) (other verbal adjuncts) ... a hipe with any of these elements is a hipe kaza

A nandau hipe can also be called hipe baga

Where the RHS NP is the O argument and the LHS NP is the A argument.

A hipe can be an argument in a clause ... just as a fandau can. For example ...

The kitten playing with the string and the monkey eating the cake were very amusing. ???

(a noun would have the determiner "this", a hipe has the determiner "thus" wedi(if you demonstrate the action)or wede (if someone else demonstrates the action))

???

..

.. The indicative

..

The indicative is the most complicated verb form by far.

The indicative is called the hukəpe

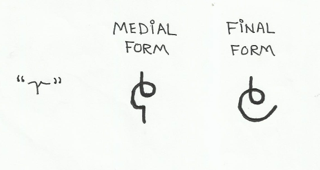

But first we must introduce a new letter.

..

..

This letter has not been mentioned so far because it doesn't occur in any words as such.

If you hear "r", you know you are hearing the main verb of a clause.

This "r" and the suffixes attached to it, are what is known as the verb-train (translated from beu)

One quirk of the beu orthography is that all instances of "o" in the verb train are dropped. A quirk of the ORTHOGRAPHY, not the phonology, so remember to pronounce these "o"s.

..

.... Agent

..

The first piece of information that must be given in the indicative is who does the action. To do this you first ...

1) Deleted the final vowel from the infinitive.

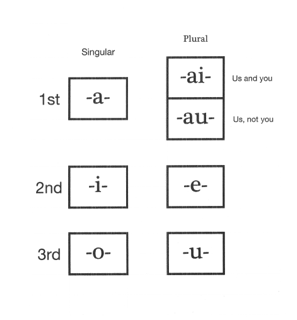

2) Then one of the 7 vowels below is must be added. These indicate the doer..

Notice that there are 2 entries that represent the 1st person plural subject (i.e. we). The top one represents first person inclusive and the bottom one represents first person exclusive.

Note that the ai form is used when you are talking about generalities ... the so called "impersonal form" ... English uses "you" or "one" for this function.

The above defines the "person" of the verb. Then follows an "r" which indicates the word is an verb in the indicative mood. For example ...

doika = to walk

doikar = I walk

doikair and doikaur = we walk

doikir = you walk

doiker = you walk

doikr = he/she/it walks ... ( pronounced DOIKOR )

doikur = they walk

..

... Tense/aspect

..

The bare "r" is for timeless statements, also tends to be used for habitual statements, especially when an adverb of time is mentioned. We can call this the "aortist".

1) doikar = I walk

For the past tense you add "i" after the "r".

2) doikari = I walked

For the future tense you add "u" after the "r".

3) doikaru = I will walk

For the present tense you use the copula and a participle.

4) sar doikala = I am walking

And of course by tensing the copula you can make the following.

5) sari doikala = I was walking

6) saru doikala = I will be walking

For the perfect you add "a" after the "r".

7) doikara = I have walked

And for the pluperfect you add "ai" after the "r".

8) doikarai = I had walked

And for the future perfect you add "au" after the "r".

9) doikarau = I will have walked

So there we are ... we have 9 tense/aspect distinctions in all.

..

.. Negation

..

To negate any of the above, you add a "j" before the tense/aspect vowel and after the indicative "r".

For the aortist, the negative is formed by adding "jo". For example ...

doikarj = I do not walk ... ( pronounced DOIKARJO )

?????????????????

"not yet" is translated by the word jindin after the negated verb. Or jindin can be used by itself in answer to a question. "already" can be translated by the word duˋ after the verb. Or duˋ can be used by itself in answer to a "yes/no" question given using the perfect.

?????????????????

..

.. Evidence

..

There are three markers that cites on what evidence the speaker is saying what he is saying. You do not have to stipulate on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. Most occurrences of the indicative verb do not have an evidence marker.

The markers are as follows ...

a) doikrin = "I guess that he walked" ... That is, worked out from some clues.

b) doikris = "They say he walked" ....... That is you have been told by some third party.

c) doikria = "he walked, I saw him"

Note that the eye witness evidential only works with the past tense.

For the aortist, the evidence affixes are "on" and "os".

doikrn = I guess that he walks ( pronounced DOIKORON )

doikrjs = They say she does not walk ( pronounced DOIKORJOS

..

.. The subjunctive

..

The subjunctive verb form comprises the same person/number component as the indicative, followed by "s".

The subjunctive is called the sudəpe

The main thing about the subjunctive is that it is not "asserted" ... it is not insisted upon ... there is a shadow of doubt as to whether the action will actually take place.

This is in contrast to the indicative mood. In the indicative mood things definitely happen.

There are three places where the subjunctive turns up.

1) There are a set of leading verbs that always change there trailing verbs to the subjunctive. For example, the leading verbs "want", "wish", "prefer", "request/ask for", "suggest", "recommend", "love/like", "think/judge", "be afraid", "demand/command", "let/allow", "advise", "forbid" etc etc. Often with the above there is a particle ta immediately after the leading verb. However taˋ can be dropped sometimes.

2) After haˋ "if". For example haˋ doikos, doikas = If he walks, I will walk

Note the gap between the two parts of the sentence.

The above can be reconfigured a bit ... doikaru haˋ doikos = I will walk if he walks

Note that the first verb is in indicative form. Also no gap is needed (although you can put one in if you want)

"if only I could walk" ... the exact same construction is used in beu for wishful thinking.

3) As part of stand alone clauses ...

doikas = "should I walk" or "let me walk" or "how about me walking" or "can I walk" or "maybe I should walk"

There is never any need for the question particle ʔai? ... even though some of my translations are questions in English.

doikis = "maybe you should walk" or "why don't you walk" or "how about you walking"

doikos = "let him walk"

doikos jono = "let John walk"

For transitive verbs ...

timpos baus waulo = let the man hit the dog

SAVE GOD KING ????????? = God save the king

TAKE DEVIL HIM ???????? = May the Devil take him

Note that for the subjunctive in a stand alone clause there is a fixed word order ... V S or V A O .

The negative subjunctive is formed by adding ka. For example ...

doikoska = best not to let him walk

It is a convention in beu that the "a" is always dropped. I will follow that convention in my transliteration. So ... doikosk from now on.

They locked him up so that he would starve to death

They let him out at night so that he would not starve to death

..

.. The imperative

..

This is used for giving orders. When you utter an imperative you do not expect a discussion about the appropriateness of the action (although a discussion about the best way to perform the action is possible).

For non-monosyllabic verbs ...

1) First the final vowel of the infinitive is deleted and replaced with u.

doika = to walk

doiku = walk !

For monosyllabic verbs u is prefixed.

dó = to do

udo = do it !

The negative imperative is formed by putting the particle kyà before the infinitive.

kyà doika = Don't walk !

..

..... Short verb

..

In a previous lesson we saw that the first step for making an indicative, subjunctive or imperative verb form is to delete the final vowel from the infinitive. However this is only applicable for multi-syllabe words.

With monosyllabic verbs the rules are different.

For a monosyllabic verbs the indicative endings and subjunctive suffixes are simply added on at the end of the infinitive. For example ...

swó = to fear ... swo.ar = I fear ... swo.ir = you fear ... swo.or = she fears ... swo.uske = lest they fear ...... etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in ai or oi, the final i => y for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

gái = to ache, to be in pain ... gayar = I am in pain ... gayir = you are in pain ... etc. etc.

For a monosyllabic verb ending in au or eu, the final u => w for the indicative and subjunctive. For example ...

ʔáu = to take, to pick up ... ʔawar = I take ... etc. etc.

dàu = to arrive

cái = to depart

..

The above is the general rules for short verbs, however the 37 short verbs below the rules are different.

Their vowels of the infinitive are completely deleted for the indicative and subjunctive verb forms. For example ...

myàr gì = I love you ........................ not * mye.ar gì

pòr nambo = he enters the house ... not *poi.or nambo

| ʔái = to want | |||

| mài = to get | myè = to like, to love | ||

| yái = to have | |||

| jòi = to go | jwèu = to undergo, to bear, to endure, to stand | ||

| fà = to know | fyá = to tell | flò = to eat | |

| bái = to ascend | byó = ??? | blèu = to hold | bwá = to exit |

| gàu = to descend | glà = to store | gwói = to pass | |

| dó = to do | dwé = to come | ||

| lái = to change | |||

| cài = to use | cwá = to cross | ||

| sàu = to be | slè = ??? | swé = to speak, to say | |

| kó = to see | kyò = to show | klói = to think | kwèu = to turn |

| pòi = to enter | pyói = ??? | plèu = to follow | |

| tèu = to put | twé = to meet | ||

| wàu = to own | |||

| náu = to give | nyáu = to return | ||

| háu = to be good |

The imperative suffix is -ya for singular and plural for all short verbs. For example ...

unyau nambo = go home !

uzwo = fear !

ugai = be in pain !

uʔau ʃì = take it !

Some nouns related to the above ... yaivan = possessions, property, flovan = food, dovan = products, nauvan = tax, tribute, glavan = reserves, dó = things that must be done, dwái = deeds, acts, actions, behaviour.

A particle related to the above ... yú ... a particle that indicates possession, occurs after the "possessed" and before the "possessor.

..

..... The copula

..

The three components of a copular clause have a strict order. The same order as English in fact. Also the copula subject is always unmarked.

The copula is sàu.

The indicative mood is derived from the infinitive in the usual method. So ...

sàr = I am

sàir = we are

sàur = we are

ʃìr = you are

sèr = you are

sòr = he/she/it is

sùr = they are

One thing is of note ... sòr and sùr are usually shortened to simply r, and appended directly to the copula subject. For example ...

jono r jini tè tomo r tumu = John is clever but Thomas is stupid.

wìa r wikai tè nù r yubau = We are weak but they are strong

If the copular subject ends in a consonant, then sòr and sùr are shortened to or and ur. Note that they lose their tones as they are phonologically part of the last word of the subject NP. That is they are an enclitic.

The only time this shortening does not happen is ahter the relativizer hu.

The rest of the verb train is built up as per usual, except for one thing. k is the negating affix instead of j. In the aortist tense ke is the negating affix instead of jo. For example ...

sorke = he/she is not

Also e is the epenthetic vowel (instead of o) when you want to append an evidential marker to the aortist tense. The e in ke and the epenthetic e are never written in the beu orthography. I will follow that tradition when I am rendering beu in the latin alphabet.

??????????

There are 2 more words that might be considered copula ...

1) twài = to be located, to be placed .... perhaps an eroded form of a participle of tèu "to place"

2) yór = to exist ... a third person indicative form of the verb yái "to have". The third person indicative meaning is completely bleached in this usage.

???????????

..

..... The time of the day

kòi = sun, day (24 hours)

The béu day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called cuaju

The time of day is counted from cuaju. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called ajai (normally just called ajai, but cúa ajai or ajai yanfa might also be heard sometimes).

| 6 o'clock in the morning | cuaju |

| 8 o'clock in the morning | ajai |

| 10 o'clock in the morning | ufai |

| midday | ibai |

| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | agai |

| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | idai |

| 6 o'clock in the evening | ulai |

| 8 o'clock in the evening | icai |

| 10 o'clock at night | ezai |

| midnight | okai |

| 2 o'clock in the morning | apai |

| 4 o'clock in the morning | atai |

Just for example, let us now consider the time between 4 and 6 in the afternoon.

16:00 would be idai : 16:10 would be idaijau : 16:20 would be idaifau .... all the way up to .... 17:50 which would be idaitau

Now all these names have in common the element idai, hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called idaia (the plural of idai). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties".

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called cuajua. This is a back formation. People noticed that the two hour period after the point in time ajai was called ajaia(etc. etc.) and so felt that the two hour period after the point in time cuaju should be called cuajua. By the way, all points of time between 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. MUST have an initial cuaju. For example "ten past six in the morning" would be cuaju ajau, "twenty past six" would be cuaju afau and so on.

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened idaia.pi

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them apaiʔe.

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued nàn ufau, for 2 hours : nàn ajai (nàn means "a long time")

In English we divide the day up into hours, minutes and seconds. In béu they only have the yanfa. The yanfa is equivalent to 5 seconds. We would translate "moment" as in "just a moment" as yanfa also.

..

..... Ordinal numbers & fractions

..

To get an fractional number (regarded as specifiers ... as all numbers are) you just attach s- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| a unit | saja |

| a half | sauva |

| a third | saiba |

| a quarter | sida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

These are fully numbers. They are written in the same way as numbers, except the have a squiggle above them. The squiggle looks like an "8" on its side that hasn't fully closed.

..

To get an ordinal number (regarded as adjectives) you just attach n- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| first | naja |

| second | nauva |

| third | naiba |

| fourth | nida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

May be this form originally came from an amalgamation of nò plus the number.

These forms are adjectives 100% and are always written out in full.

..

To get (I don't know what these are called) (regarded as a noun) you just attach b- to the front of the cardinal number. So we have ;-

..

| alone, single | baja |

| a double, a twosome, a duality | bauva |

| a threesome, a trinity | baiba |

| a foursome, a quartet | bida |

| etc. | etc. |

..

Note bajai = lonely

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences