Béu : Chapter 5: Difference between revisions

| Line 404: | Line 404: | ||

A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no". | A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no". | ||

To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a | To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a "yes" or "no" answer), the particle '''ʔai''' will come at the very end. | ||

''' | Now this is the only single syllable word that can not be said to be low tone or high tone (well I suppose there are the short verbs found in the verb chains as well). | ||

It starts of neutral tone and rises. In fact if you look in chapter 1 and look at the intonation profiles of the interjections, you will see how '''ʔaiwa''' is pronounced. '''ʔai''' is pronounced exactly as the first part of '''ʔaiwa'''. In '''beu''' orthography, this word is given its own symbol ... a double spiral. I will write it as '''ʔai?''' ... why not. | |||

'''ʔai''' is neutral as to the response you are expecting. | |||

To answer a positive question you answer '''ʔaiwa''' "yes" or '''aiya''' "no". For example ... | To answer a positive question you answer '''ʔaiwa''' "yes" or '''aiya''' "no". For example ... | ||

Revision as of 23:18, 2 December 2015

..... ké, bò and hí

..

These are 3 little nouns that have become grammatical particles also.

Below are the words with their original meaning.

ké = result, consequence

bò = case, example, instance

hí = source, origin

Now while these words are still used as nouns, they have developed a longer form ... possibly to reduce ambiguity with the particulate usage.

ké => kegozo = result, consequence ... (gozo = fruit)

bò => bozomba = case, example, instance ... (somba = to sit)

hí = => hidito = source, origin ... (dito = point, dot)

..

... the apodosis marker ké

..

This particle is mandatory for the main clause in an "if sentence"

This particle comes before the "consequence clause" (main clause). Usually English does not require a particle here although "then" is sometimes optionally used in this position.

Mandarin has a mandatory particle in this position. "jiù"

By the way ... kepe = apodosis

..

... the protasis marker bò

..

This word means "if". "If" is used to introduce a conditional sentence in English. A conditional clause always comprises two clauses ( usually called protasis and the ??? )

The béu the verbs in both clauses in the sentence should be in the subjunctive. For example ...

bò jìs london ... ké jàs glasgow = If you go to london (then) I will go to Glasgow

Actually the bò clause and the ké clause can be in any order (as they can be in English) ...

ké jàs glasgow ... bò jìs london ... = If you go to london (then) I will go to Glasgow

When the speaker has a lot of doubt that the condition will be met, bola is used instead of bò

When the speaker has very little doubt that the condition will be met, he would use kyu? instead of bò. When this happens the ké is dropped.

By the way ... bope = protasis ??

bò is also a complementizer ... that is, it is equivalent to "that" in the sentence "I think that she is very beautiful"

Notes on translating "whether" ...

Sometimes you get an English "whether" sentence translated using bò and ké ...

bò myìs lú jù ... ké tomorrow jàr dublin = whether you like it or not, I am going to Dublin tomorrow

Note that the protasis verb is in its subjunctive form and the ???? verb is in its indicative form.

However this is a bit unusual, normally bò and ké are not considered necessary. So ....

myìs lú jù ... tomorrow jàr dublin = whether you like it or not, I am going to Dublin tomorrow

... the agent marker hí

..

béu has a passive form, achieved by infixing -w.

When you have a passive, the agent can optionally be given. When given it is preceded by the particle hí.

..

..... Word building

..

Many words in béu are constructed from amalgamating two basic words. The constructed word is non-basic semantically ... maybe one of the concepts needed for a particular field of study.

..

In béu when 2 nouns are come together the second noun qualifies the first. For example ...

toili nandau (literally "book" "word") ... the thing being talk about is "book" and "word" is an attribute of "book".

Now the person who first thought of the idea of compiling a list of words along with their meaning would have called this idea toili nandau.

However over the years as the concept toili nandau became more and more common, toili nandau would have morphed into nandəli.

Often when this process happens the resulting construction has a narrower meaning than the original two word phrase.

There are 4 steps in this word building process ...

1) Swap positions : toili nandau => nandau toili

2) Delete syllable : nandau toili => nandau li

3) Vowel becomes schwa : nandau li => nandə li

4) Merge the components : nandə li => nandəli

The above example is for 2 non-monosyllabic words. In the vast majority of constructed words the contributing words are polysyllables.

The process is slightly different when a contributing word is a monosyllabic. First we look at the case when the main word is a monosyllable ...

wé deuta (literally "manner soldier")

1) Swap positions : wé deuta => *deuta wé ........ there is no step 2

3) Vowel becomes schwa : *deuta wé => *deutɘ wé

4) Merge the components : *deutə wé => deutəwe

And the case when the attribute is a monosyllable ...

mepe hí (literally "form origin")

1) Swap positions : *hí mepe

2) Delete syllable : *hí pe .......................................... there is no step 3

4) Merge the components : *hí pe => hipe

And the case when the attribute ends in a consonant ...

megau peugan ... "body of knowledge" "society"

1) Swap positions : *peugan megau

2) Delete syllable : *peugan gau

3) Delete the coda and neutralize the vowel :*peugan gau => *peugə gau

4) Merge the components :*peugən gau => peugəŋgau

And the case when the main word has a double consonant before the end vowel ...

kanfai gozo ... merchant of fruit

1) Swap positions : *gozo kanfai

2) Delete syllable : *gozo fai ............................. Note kan is deletes, not just ka

3) Vowel before the final consonant becomes schwa :*gozo fai => *gozə fai

4) Merge the components :*gozə fai => gozəvai

There are no cases where both contributing words are monosyllables.

Note ...

1) the schwa is represented by a sturdy dot.

2) the consonant before the schwa takes its final form

3) the consonant after the schwa takes its medial form

When spelling words out, this dot is pronounced as jía ... meaning "link".

Notice that when you hear nandəli, deutəwe or peugəgau you know that they are a non-basic words (because of the schwa).

Also when you see nandəli or deutəwe, peugəgau written you know that they are non-basic words (because of the dot).

However when you come across hipe it is not immediately obvious that it's a non-basic word.

This method of word building is only used for nouns.

..

..... Six special verbs

..

The verb yái means "to have on your person" or perhaps "to have easy access to" if we are talking about a larger object. For example ...

jonos yór ama = John has an apple

As with all transitive verbs it has a passive form.

jono yawor = John is present .... short for jono yawor hí día

ama yawor hí jono = The apple is on John's person

....

The verb wàu means "to possess legally" to "own"

jenes wàr wèu = Jane owns a car

And the passive form ...

wéu wawor hí jene = The car is owned by Jane

....

yái is also used to show location.

ʔupais yór bode = "there are small birds in the tree"

Note ... a copular expression can also be used to express the above ...

....

"There is a God" => God is real

"There is no God" => God is imaginary

....

’’’yái’’’ = to be in possession of (on you) …….……. slight obligation => might ???

‘’’wàu’’’ = to possess (legally) ………………………. obligation/duty => inevitability

‘’’???’’’ = to reach for ………………………............. try

‘’’blèu’’’ = to hold ………………………................... ability => sometimes

to pass ....... to manage/to succede

reach ......... start

leave ......... stop

to duck ..... to stop off from/take a break from

to continue

come on / yalla

..

..... And Or

..

In the last chapter we said that when 2 nouns come together the second one qualifies the first.

However this is only true when the words have no pilana endstuck. If you have two contiguous nouns suffixed by the same pilana then they are both considered to contribute equally to the sentence roll specified. For example ...

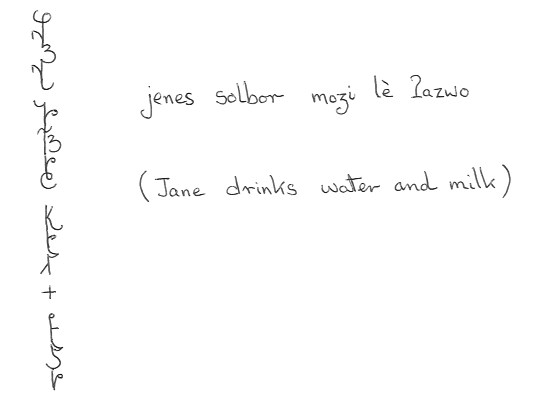

jonos jenes solber moʒi = "John and Jane drink water"

In the absence of endstuck pilana, to show that two nouns contribute equally to a sentence (instead of the second one qualifying the first) the particle lè is placed between them.

This is one of these words that is never written out in full but has its own symbol. See below ...

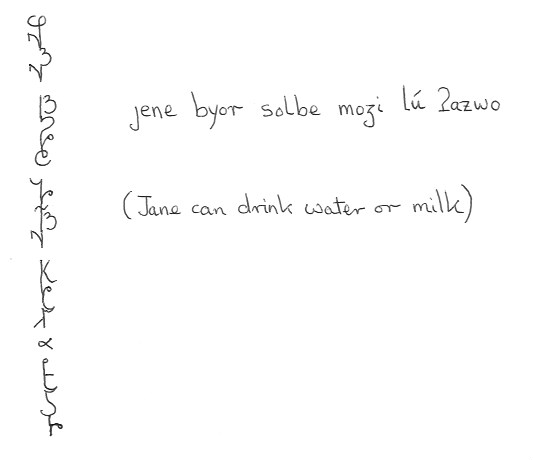

Another similar particle is lú meaning "or". Its also has a special symbol. See below ...

jene byor solbe moʒi lú ʔazwo = "Jane can drink water or milk" .... is it jene or jenes ???

jonos jenes kuri auva sadu lè aiba ʔusʔa faja dí = John and Jane have seen two elephants and three giraffes this morning. ???

In béu as in English If it is obvious to the listener that a string of nouns are going to be given then they can be annunciated with just a slight pause between them. However lè must always separate the last from the second last. But having lè between every member of a list is also permissible.

..

..... Bicycles, Insects and Spiders

..

wèu = vehicle, wagon

weuvia = a bicycle

weubia = a tricycle

Perhaps can be thought of derived from an expression something like "wagon two-wheels-having" or "wagon double-wheel-having" with a lot of erosion.

Notice that the "item" that is numbered (i.e. wheel) is completely dropped ... probably not something that would evolve naturally.

There are not many words in this category.

joduʒia* = spider

jodulia = insect

jodugia = quadraped

joduvia = biped

nodebia = a three-way intersection ... usually referring to road intersections.

nodegia = a four-way intersection

nodedia = a five-way intersection

nodelia = a six-way intersection ... and you can continue up of course.

*jodu = animal ... from jode = to move

..

..... Ambitransitive verbs

..

In English there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes involve two participants. For example "knit" or "turn". In English you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up after the verb (that is ... an O argument has turned up) ... S and A appear the same in English.

Similarly in béu there are some verbs that sometimes take one participant and sometimes take two participants. For example mekeu "knit" or kwèu "turn". In béu you know if the verb is appearing in its intransitive form if an extra argument turns up with the ergative marker -s attached (that is ... an A argument has turned up) ... S and O appear the same in béu.

Note on nomenclature

Dixon calls "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitive verb of type S=A or an [S=A ambitransitive verb].

I call "knit"/mekeu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one unaffected argument" or an [unaffected ambitransitive verb].

For "knit" the preverb argument* is either S or A .... For mekeu the unaffected argument is either S or A.

Dixon calls "turn"/kwèu is an ambitransitive verb of the type S=O or an [S=O ambitransitive verb].

I call "turn"/kwèu an ambitransitibe verb of type "one affected argument" or an [affected ambitransitive verb].

For "turn" the affected argument is either S or O .... For kwèu the naked argument** (i.e. no -s) is either S or O.

*It is also the unaffected argument.

**It is also the affected argument.

..

..... More on definiteness

..

In the section on word order we said that when the person being spoken to can identify X as one particular X ... then X will come before the verb, where X is any of the A O or S arguments.

However ... the above leaves undefined, whether the person speaking can identify X. This can be made explicit in béu by adding either the particle é or the participle fawai. For example ...

doikora bàu = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known-ness to the person speaking is not defined.

doikora é bàu = Some man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : unknown to the person speaking.

doikora bàu fawai = A man is walking .... unknown to the person being spoken to : known to the person speaking.

This distinction is also made in certain natural languages. For example with nouns in Samoan ...

o sa fafine = a woman

o le fafine = a woman ……. unknown to you but known to me

Or between these two indefinite pronouns in Latin ...

aliquis = somebody

quidam = somebody ……. unknown to you but known to me

[ Note ... the argument qualified by é or fawai invariably come after the verb. Also, while it is possible to imagine some scenario where an argument is known to the person being spoken to but unknown to the person speaking, in reality this very very rarely happens and I know of no natural language that makes this distinction. ]

..

One interesting point .....

Take the sentence ... "She wants to marry a Norwegian"

How do we show the definiteness of the Norwegian in relation to the subject. That is ... does she have a certain Norwegian in mind or does she want to marry any Norwegian.

In English ... when you hear this sentence ... you will nearly always know from the context, which of the two meanings is meant.

"any" or "that she knows" could be added to make the distinction explicit within the sentence itself.

..

..... Polar question and focus

..

A polar question is a question that can be answered with "yes" or "no".

To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a "yes" or "no" answer), the particle ʔai will come at the very end.

Now this is the only single syllable word that can not be said to be low tone or high tone (well I suppose there are the short verbs found in the verb chains as well).

It starts of neutral tone and rises. In fact if you look in chapter 1 and look at the intonation profiles of the interjections, you will see how ʔaiwa is pronounced. ʔai is pronounced exactly as the first part of ʔaiwa. In beu orthography, this word is given its own symbol ... a double spiral. I will write it as ʔai? ... why not.

ʔai is neutral as to the response you are expecting.

To answer a positive question you answer ʔaiwa "yes" or aiya "no". For example ...

glá è hauʔe ʔái = Is the woman beautiful ? .......... If she is beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she isn't answer aiya.

To answer a negative question you can not use ʔaiwa or aiya but must repeat the whole sentence in either the negative or the positive.

glá sorke hauʔe ʔái = Isn't the woman beautiful ? .... If she is beautiful, answer glá è hauʔe, if she is not answer glá sorke hauʔe

Sometimes it is permissible to drop everything except the verb (which of course incorporates the negative element).

To bring a word into focus you put cù in front of it. For example ...

Statement ... bàus glán nori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Focused statement ... bàus cù glán nori alha = It is the woman to whom the man gave flowers. (English uses a process called "left dislocation" to give emphasis to a word).

Statement ... bàus ná glá hauʔe nori alha = the man gave flowers to the beautiful woman

Focused statement ... bàus ná cù glá hauʔe nori alha = It is to the beautiful woman that the man gave flowers to.

Any argument can be focused in this way. In fact the verb can also be focused using this method.

To question one element in a clause, you have cù in front of the element and ʔái sentence final.

Alternatively you can dispense with the cù and put the ʔái directly behind the element you want to question. For example ...

cù bàus glán nori alha ʔái = Is it the man that has given flowers to the woman ?

bàus ʔái glán nori alha = Is it the man that has given flowers to the woman ?

[ should I replace cù with á]

..

..... Content questions

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 7 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

béu has 7 content question words also ...

..

| nén nós | what |

| mín mís | who |

| kái | "what kind of" |

| láu | "how much" or "how many" |

| nái | which |

..

nós and mís are the ergative equivalents to nén and mín (the unmarked words)

There is a strong tendency for nén nós mín and mís to be sentence-initial.

There is a tendency for the NP's containing kái, láu and nái to be sentence-initial.

kái and nái come after the nouns they ask about.

láu comes before the noun it asks about. ??? [ this doesn't agree with what I wrote in fandaunyo Chapter 2 ... but maybe láu in number slot : kái in adjective slot and nái in determiner slot }

"when" is represented by kyù nái (which occasion) ... "where" by dá nái (which place)

"how" is represented by wé nái (which way) ... "why" by nenji (for what)

The pilana are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.

Here are some example ...

Statement ... báus glán nori alha = the man gave the woman flowers

Question 1 ... mís glán nori alha = who gave the woman flowers ?

Question 2 ... minon bàus nori alha = the man gave flowers to who ?

Question 3 ... nén bàus glán nori = what did the man give the woman ?

Question 4 ... ná glá nái bàus nori alha = the man gave the flowers to which woman ?

Question 5 ... só bàu nái glán nori alha = which man gave the woman flowers ?

Question 6 ... alha kái báus glán nori = what type of flowers did the man give the woman ?

Question 7 ... láu alha báus glán nori = how many flowers did the man give the woman

..

Note ... In English as in about 1/3 of the languages of the world it is necessary to front the content question word.

..

.. Specifiers X determiners

..

Below is a table showing all the specifiers plus a countable noun plus the proximal determiner "this".

..

| 1 | ù báu dí | all of these men OR all these men |

| 2 | hài báu dí | many of these men |

| 3 | iyo báu dí | few of these men OR a few of these men |

| 4 | auva báu dí | two of these men => ataitauta báu dí ... 1727 of these men |

| 5 | jù báu dí | none of these men |

| 6 | í báu dí | any of these men OR any one of these men |

| 7 | é báu dí | one of these men |

| - 8 - | éu báu dí | some of these men |

| 9 | ?? báu dí | every one of these men |

| 10 | nò báu dí | several of these men OR several of these men here |

| 11 | é nò báu dí | one or more of these men ??? |

| 12 | í auva báu dí ... | any 2 of these men => í ataitauta báu dí ... any 1727 of these men |

..

The above table is worth discussing ... for what it tells us about English as much as anything else.

..

One line 1 ... I do not know why "all these men" is acceptable ... on every other line "of" is needed (to think about)

Similarly on line 3 ... I do not know why "a few" is a valid alternative.

Notice that *aja báu dí does not exist. It is illegal. "one of these men" is expressed on line 7. aja only used in counting ???

I should think more on the semantic difference between line 10 and line 8. ???

line 1 and line 9 are interesting. Every language has a word corresponding to "every" (or "each", same same) and a word corresponding to "all". Especially when the NP is S or A, "all" emphasises the unity of the action, while "every" emphasises the separateness of the actions. Now of course (maybe in most cases) this dichotomy is not needed. It seems to me, that in that case, English uses "every" as the default case (the Scandinavian languages use "all" as the default ??? ). In béu the default is "all" ù.

On line 9, it seems that "one" adds emphasis to the "every". Probably, not so long ago, "every" was valid by itself. The meaning of this word (in English anyway) seems particularly prone to picking up other elements (for the sake of emphasis) with a corresponding lost of power for the basic word when it occurs alone. (From Etymonline EVERY = early 13c., contraction of Old English æfre ælc "each of a group," literally "ever each" (Chaucer's everich), from each with ever added for emphasis. The word still is felt to want emphasis; as in Modern English every last ..., every single ..., etc.)

..

This table is also valid for the distal determiner "that". For the third determiner ("which") the table is much truncated ...

..

| 1 | nò báu nái | which men |

| 2 | ... auva báu nái | which two men => ataitauta báu nái which 1727 of these men |

..

Below I have reproduced the above two tables for when the noun is dropped (but understood as background information). It is quite trivial to generate the below tables. Apart from lines 8 and 10, just delete "men" from the English phrase and báu from the béu phrase. (I must think about why 8 and 10 are different ???)

..

| 1 | ù dí | all of these OR all these |

| 2 | uwe dí | many of these |

| 3 | iyo dí | few of these OR a few of these |

| 4 | auva dí | 2 of these => ataitauta dí ... 1727 of these |

| 5 | kyà dí | none of these |

| 6 | í dí | any of these OR any one of these |

| 7 | é dí | one of these |

| - 8 - | è dí | some of these OR several of these |

| 9 | yú dí | every one of these |

| 10 | nò dí | these NOT several of these |

| 11 | é nò dí | one or more of these |

| 12 | í auva dí ... | any 2 of these => í ataitauta dí ... any 1727 of these |

..

| 1 | nò nái | which ones |

| 2 | ... auva nái | which two => ataitauta nái which 1727 |

..

In the last section we introduced the rule, that when a determiner is the head, then the determiner changes form (an a is prefixed to it)

Now we must introduce an exception to that rule ... when you have a specifier just to the left of a determiner (in this conjunction, the determiner MUST be the head) the determiner takes its original form.

..

..... Mmmh

..

| I | pás | só pà | we | yúas | só yùa |

| we | wías | só wìa | |||

| you | gís | só gì | you | só jè | |

| he, she | ós | só ò | they | só nù | |

| it | ʃís | só ʃì | they | ʃís | só ʃì |

| Noun | Particle for a headless relative clause | ||

| kyù | occasion, time | kyù | "the time that", when |

| dá | place | dà | the place that |

| kài | sort, type | kai.a | "the type that", "as" |

| làu | amount | lau.a | the amount that |

..

The particle for an ergative headless relative clauses about things or persons is so.a ( maybe this can be considered a contraction of só ʃì à or só ò à ... by the way, these two forms are never found )

The particle for a non-ergative headless relative clauses about things is ʃi.a (this can definitely be considered a contraction of ʃì à ... the form ʃì à is never found although it is valid by the rules of grammar)

The particle for a non-ergative headless relative clauses about persons is o.a (this can definitely be considered a contraction of ò à ... the form ò à is never found although it is valid by the rules of grammar)

The head of headless relative clauses about people ... ò à or só ò à ... nù à or só nù à ... well actually any pronoun can be patterned like this.

..

The house cell

In the Christian religion, for the average adherent, the hour spent in church on Sunday represents the main obligation ... in terms of time anyway. Of course most Christians support their church financially and often their devotion results in some socialising with their fellows believers. This socializing usually has the aim of doing good-works but of course people enjoy socializing and these get-togethers often supply moral support with respect to personal problems and probably there is mutual re-enforcing of beliefs and a feeling of "solidarity" with respect to life's problems and the rest of the world in general.

The main time demand for a beuki is not sitting in a church listening to sermons but privately reading. This reading is done in a special room called a "cell". The volumes containing the body of knowledge that is considered "canonical" is read.

This reading is the most basic obligation however and most also go in for other "duties" such as dietary restrictions and prescribed daily excercise routines (to some extent at least). Many also volunteer time and money to the many activities which are proscribed by béu to promote personal happiness and social cohesion (these activities are actually designed to have the results (mentioned in the above paragraph) which seems like a chance by-product of certain Christian practices).

Other sections will go into detail about the duties touched on above. However this section is only about how the requirement to spend a certain time each day, reading the body of knowledge that béu considers "canonical" * affects the architecture of the typical béu followers place of residence.

..

..

The above shows the plan view of a "cell" : the room in which the reading of the "canonical" works is done. There is usually a cell in every family dwelling. It is a requirement that the cell is perfectly square and is windowless. Also the only lighting permitted is two oil lanterns fitted over either shoulder of the "reader" to cast light over the top of the lectern.

Behind the door is situated the bookcase that contain the "tomes" that constitute the béu canon. It is attached to the wall as opposed to standing on the floor. It can also be recessed into the wall.

Facing the door there is a large tapestry (a poster would also do). The image is usually of an awe-inspiring view of nature. However colourful fractals or geometric patterns are also quite common.

The rectangular object is a lectern. And behind the lectern is a comfy seat. And either side of the seat (above on the wall) are two lanterns.

As can been seen, the seat and the lectern are quite low. The chair is legless and the usual method is just to cross your legs on the floor just to the front of the seat.

It is common to excercise and bathe before doing your daily reading. Also many change into loose robes of a light blue colour, before entering the cell.

On the wall facing the lectern is "the shelf".

..

..

Below is shown a robe that is optionally put on before entering the cell to read. It is light blue ... quite similar to a robe that an Egyptian peasant would wear.

..

..

Below is shown the shelf attached to the wall facing the reader. About 4 or 5 feet of the ground. It is in the shape of an ellipse from which a third has been cut off from the depth, allowing it to be flush with the wall. In the middle is a small naked flame in a glass. Either side of the are two oblong vases with flowers. On the extremities (over the focuses) are two objects d'art. (the support or supports for the shelf are not shown)

..

..

Below is shown one of the lanterns. Obviously to prevent fire these ate placed in fairly substantial brackets connected to the wall.

..

..

Other items sometimes found in the cell ...

The books are meant to be read in 20 minute sittings and there is ofter an egg-times that counts out about 20 minutes. Usually about 6 inches high and kept on a special indentation on the lectern

A large glass goblet filled with marbles. They are numbered and come in different sizes. Used for keeping a record of what chapters have been read. All the marbles from one book would have the same size and colour. Perhaps inside the lectern is a large wooden tray with indentations. One indentation for every marble. When the goblet is empty and the tray is full, the course of study has been completed.

Large cards. A bit like playing cards but bigger and more solid. Each with intricate designs on it. Usually some sort of fancy box for them as well. These are for keeping a record of what chapters have been read.

Obviously if you have the cards you won't need the goblet and vice versa.

..

- At the present time, the body of work that is considered "canonical", consists of 15 volume (at the present time)s. However unlike other movements ... in béu, there is actually a mechanism for updating and improving these "proscribed books". The very opposite to every other religion. Every other religion has shown a strong instinct to hastily gather a body of script together and then to "set it in stone" ... well that is a by-product of our mental make-up. Hopefully the results of a more deliberate method will also be considered worthy of reverence ( or a little consideration at least :-) ).

..

The "canon"

Well there is the main volume of course ???

..

Then there is the 5 volumes containing the "5 main subjects".

History ... I have temporarily made Jared Diamonds book, "Guns, Germs and Steel" canonical (until the proper tome can be written of course).

Mathematics ...

Chemistry ... (maybe 30 % of the pages of this book will be given over to organic chemistry)

Physics ... Actually more comprising what I would call Engineering Science ( motion of bodies, forces and their direction within a bridge, etc. etc. )

The language of Béu ... actually a broader linguistic course

..

Then there is the 5 volumes containing the "5 minor subjects".

Human Physiology/Health ... maybe about 10 % of the pages of this book will be given over to how other animals do things (after first explaining how the human body does things of course)

The Civil Society which surrounds the beuki ... for example banking system, mortgages, local government, central government, tax, how the tax money is spent etc.etc.

Geology ...

Geography ... physical shape and how countries interconnect ... populations and population growth ... stage of development ( country by country or region by region )

Accounting/economics ...

..

We soon get on to "practical" subjects, such as metalwork, which is not really suited to be learnt solely from a book. So no more subjects needed ... better to restrict them to 10.

..

Then there is the x volumes concerning behaviour. (That is interpersonal relations)

General behaviour ... I have temporarily made Dale Carnegie's book, "How to win friends and influence people" canonical (until the proper tome can be written of course).

Husband <--> Wife ... I have temporarily made Nancy Van Pelt's book, "Highly Effective Marriage" canonical (until the proper tome can be written of course).

Employee <--> Employer ... There was a very good book by two guys with Dutch sounding names ... published at least 20 years ago ... I can not remember or find the book at the moment.

Child <--> Parent ... ???

..

Then there is a smallish book about First Aid

..

..

These canonical book are not set in stone however. There will be a mechanism for updating them.

Maybe this seems like a contradiction of terms ... a canonical body of work, yet mere mortals are allowed to change it. Well for some reason it is accepted by the beuki. Of course the scholars who update the work are very respected and there is a lot of conferring done before any update (also "any" bickering about what to update, is kept well out of the public eye).

The food complex

Many of the delights of life are found in the company of fellow human beings. Especially like-minded human beings. A lot of the customs of béu are designed especially to help people find that delight, to make them feel as if they are part of something bigger than any individual, to feel as if they are part of a community. The following is a tradition that has been designed with this in mind.

Every 3 seasons everybody is expected to get together with one other person and invite 2 strangers to dine (usually it will be to a home of one of the inviters). This is arranged by the local town hall. It is to facilitate meeting people that live near to you but that you do not know well. It is meant to be an enjoyable occasion for all involved. Only the 4 people should be present. Sometimes the hosts are siblings, sometimes a couple and sometimes friends. Usually the invitees do not know each other very well ... but sometimes they are a couple. Obviously some people are not into this sort of thing so they shouldn't be forced ... but they should be encouraged to be both hosts and guests.

The parish flags

béu country is divided into "parishes". These are rural communities of 10,000 -> 50,000 people (urban areas have are distinct from rural areas and have a very different administrative structure).

The parish boundaries follow geographical features, such as streams and ridges etc. However the shape of a parish approximates to a hexagon. In fact in a total featureless landscape it would be a hexagon.

The rim banners

Each parish has 6 banner-rows along its boundaries. A banner-row consists of 17 banners about 10 m apart. Each banner is made from a pole about the girth of an adults arm or leg. Each pole is about 7.5 m high and the top 5 m of the pole has an orange banner. The cloth of the banner is about 1/3 m wide. When about half the original cloth has been weathered away the cloth should be replaced, best to do an entire banner-row at on time. These banner-rows are normally placed in prominent positions. They can be anywhere along a boundary, but it isn't considered good to have the gap too small or too big between any neighbouring banner-rows.

In sparsely populated areas you get what is called a super-parish. They are around 10 times the size of a normal parish (but their population falls within the 10,000 -> 50,000 limit). These super-parishes have 2 barrier-rows per side(that is 12 in total), and each banner-row has 19 banners. All these banner dimensions are about 15% to 20% bigger than normal.

The outer banners

About 2/3 of the way out from the parish centre there are what are called the spoke banners arranged in banner-rows. There are 4 of these banner-rows and each has 11 banners. Again these are in prominent positions and/or well visible from roads. Again they should be quite spread out from each other.

Each of there banner-rows, instead of delineating the parish boundary, point towards the administrative centre of the parish, the kasʔau.

(For a super-parish there are 8 banner-rows with 13 banners each)

The inner banners

About 1/3 of the way out from the parish centre there are what are called the spoke banners arranged in banner-rows. There are 3 of these banner-rows and each has 5 banners. Below is what a banner looks like.

Again each of these banner-rows is pointing to the kasʔau.

(For a super-parish there are 5 banner-rows with 7 banners each)

..

..... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences