Béu : Chapter 3 : The Noun: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "== ..... The 4 verb forms== === ... The infinitive verb form=== .. The infinitive is called the '''hipe''' The most common multi-syllable verbs end in "a". The less commo...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== ..... | == ..... Some fundamentals of the grammar== | ||

.. | .. | ||

The | This is an ergative language. The ergative marker is -'''s''' or -'''os''' ? for words ending in a vowel or '''sá''' for a multi-word NP. | ||

In the main clause there is free word order. That is, you can have SV, VS, AVO, AOV, VAO, OVA, OAV or VOA<sup>* | |||

The | The choices VAO/VOA and AOV/OAV are made on discourse grounds. | ||

The | The other choices are made according to the definiteness of the S, A and O arguments. | ||

If definite they come before the verb, if not they come after. | |||

''' | Note ... '''é''' and '''è''' also code for indefiniteness ... OK they are useful for oblique NP and subclauses ... when they appear with S, A or O arguments in a main clauses they impart the notion that the argument is unknown to the speaker as well (or at least that the speaker has limited interest in the argument). | ||

<sup>*</sup> Actually in a piece of discourse, it is most likely that the S or A argument are old information and probably the topic. When this is the case they are dropped and instead of the 8 sentence types shown above, we have only the 3 sentence types, V(s), O V(a) and V(a) O where V(s) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the S argument and V(a) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the A argument. | |||

== ..... Noun phrases== | |||

.. | .. | ||

There are 4 types of noun phrase in '''béu''' ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

The | 1) The noun phrase for countable nouns | ||

2) The noun phrase for uncountable nouns | |||

3) The noun phrase for pronouns | |||

4) The noun phrase for verbs | |||

5) The noun phrase for places | |||

.. | .. | ||

From now on I will not be talking about "noun phrase", but will be using the '''béu''' term '''fandaunyo'''. | |||

'''fandau''' = noun<sup>*</sup> | |||

'''fandauza'''<sup>**</sup> = "a noun phrase" | |||

'''fandaunyo'''<sup>***</sup> = "a noun or a noun phrase" | |||

<sup>*</sup>The usual word building process would give '''fanyədau''' (from '''nandau''' "word" and '''fanyo''' "thing/object"). However in this particular word, there has been a further contraction to '''fandau'''. | |||

<sup>**</sup> the suffix -'''za''', is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word". | |||

<sup>***</sup> the suffix -'''nyo''', is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word OR the basic word''. | |||

.. | |||

=== ... The countable nouns fandauza=== | |||

.. | |||

''' | It can consist of ... (1) the emphatic particle ... (2) a specifier '''koiʒi''' ... (3) a number ... (4) the head '''hua''' ... (5) adjectives '''saidau''' ... (6) a determiner ... (7) a question word ... (8) a relative clause. Only the head is mandatory. | ||

Actually there are quite a few restrictions. For example (7) would never occurs with (8) .... mmmh why did I insert "would" here ?? | |||

Many restrictions between (2) and (3) | |||

.. | .. | ||

==== .. | ==== .. The question words==== | ||

.. | .. | ||

The set of possible question word (within a NP) is very small. Only three ... '''nái''' "which", '''láu''' "how much" or "how many", '''kái''' "what kind of". | |||

.. | |||

==== .. The determiners==== | |||

.. | |||

The set of possible determiners is very small. Only two ... '''dí''' "this", or '''dè''' "that". | |||

The | |||

''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

==== .. | ==== .. The adjectives==== | ||

.. | .. | ||

Not much to say about this one, you can string together as many as you like ... the same as in English. Also genitives are put in this slot. A genitive is a word derived from a noun by the suffixing of -'''n''' (or -'''on''') which indicates possession<sup>*</sup>. Genitives always come after the regular adjective. | |||

<sup>*</sup>Actually it can also stand for a location ... where the NP is at. | |||

.. | .. | ||

==== .. | ==== .. The head==== | ||

.. | .. | ||

This is usually a noun. However it can also be an adjective. When it is an adjective it has concrete reference instead of representing a quality (as happens often in English). For instance, when talking about ... say ... a photograph, you could say "the green is too dark". In this sentence "the green" is a NP meaning the quality of being green. In '''béu''' if green is used as the head of a NP it always means "the green one" : "the person/thing that is green". | |||

''' | In '''béu''', '''geunai''' would be used in a sentence such as "the green is too dark". | ||

'''gèu''' = "green" or "the green one" | |||

''' | '''geumai''' = "greenness" | ||

'''saco''' = "slow" or "the slow one" | |||

'''saconi''' = "slowness" | |||

Notice that the suffix has two forms ... depending upon whether the base adjective has one syllable or more than one syllable. | |||

.. | Sometimes the head is a determiner. In these cases the NP is understood to refer to some noun ... but it is not spoken ... it is just understood by all parties. In these cases the determiners undergo a change of form ... | ||

'''dí''' => '''adi''' = "this one" | |||

'''dè''' => '''ade''' = "that one" | |||

''' | '''nái''' => '''anai''' = "which one" | ||

''' | Related to '''dí''' and '''dè''' are the two nouns '''dían''' (here) and '''dèn''' (there). Although nouns, they never occur with the locative case or the ergative case. | ||

.. | .. | ||

=== | ==== .. The specifiers==== | ||

.. | .. | ||

The | The specifiers = '''nandau.a koiʒi''' or just '''koiʒia''' | ||

'''koiʒi''' actually means "preface" as in "the preface to the book" | |||

''' | It also means forewarning or harbinger ... as in "that slight tremor on Tuesday night, was '''koizi''' of the quake on Friday" | ||

Immediately before the core you can have a specifier. | |||

There consist of the following ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== | '''kyà''' = no, '''í''' = any, '''é''' = some(for singular noun), '''yú''' = every, '''è''' = some(for plural nouns), '''nò''' = plural, '''ù''' = all, '''auva''' => '''ataitauta''' = 2=>1727, '''uwe''' = many, '''iyo''' = few, '''ege''' = more, '''ozo''' = less. | ||

.. | .. | ||

Notice that the specifier that implies zero number has low tone, the 3 specifiers that imply singular* number have high tone and the 3 specifiers that imply plural* number have low tone. | |||

.* Well this is true for the English translations anyway. (Side Note ... Actually I am not so sure about the "logic" of my little scheme. Also I would like to look into how a spectrum of other languages use specifiers) | |||

Also note that '''nò''' is a noun (meaning "number") as well as a particle that denotes plurality. In the '''béu''' mathematical tradition, '''nò''' means a number from 2 -> 1727 only (of course there are expressions for expanding the concept to integers, rational numbers etc. etc.) | |||

After a '''koiʒi''' the head is always in its base form with regard to number. For example ... | |||

.. | |||

''' | '''é glà''' = some woman | ||

'''è glà''' = some women ... not *'''è gala''' | |||

''' | '''í toti''' = any child .......... not *'''í totai''' | ||

.. | .. | ||

The are 4 cases where you can have two '''koiʒi''' together ... '''é nò''' or when you have '''í''' followed by a number greater than one. For example ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''é nò toti''' = some child or children ... this is a contraction of "'''é toto''' OR '''nò toti'''" | |||

'''í auva toti''' = any two children | |||

'''ege auva toti''' = two more children | |||

''' | '''ozo auva toti''' = two less children | ||

.. | |||

==== .. Specifiers X determiners==== | |||

.. | .. | ||

Below is a table showing all the specifiers plus a countable noun plus the proximal determiner "this". | |||

.. | .. | ||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| 1 | |||

|align=left| '''ù báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| all of these men OR all these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 | |||

|align=left| '''uwe báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| many of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 3 | |||

|align=left| '''iyo báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| few of these men OR a few of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 4 | |||

|align=left| '''auva báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| two of these men => '''ataitauta báu dí''' ... 1727 of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 5 | |||

|align=left| '''kyà báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| none of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 6 | |||

|align=left| '''í báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| any of these men OR any one of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 7 | |||

|align=left| '''é báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| one of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| - 8 - | |||

|align=left| '''è báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| some of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 9 | |||

|align=left| '''yú báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| every one of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 10 | |||

|align=left| '''nò báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| several of these men OR several of these men here | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 11 | |||

|align=left| '''é nò báu dí''' | |||

|align=left| one or more of these men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 12 | |||

|align=left| '''í auva báu dí''' ... | |||

|align=left| any 2 of these men => '''í ataitauta báu dí''' ... any 1727 of these men | |||

|} | |||

.. | |||

The above table is worth discussing ... for what it tells us about English as much as anything else. | |||

.. | |||

One line 1 ... I do not know why "all these men" is acceptable ... on every other line "of" is needed (to think about) | |||

Similarly on line 3 ... I do not know why "a few" is a valid alternative. | |||

Notice that *'''aja báu dí''' does not exist. It is illegal. "one of these men" is expressed on line 7. '''aja''' only used in counting ??? | |||

I should think more on the semantic difference between line 10 and line 8. ??? | |||

line 1 and line 9 are interesting. Every language has a word corresponding to "every" (or "each", same same) and a word corresponding to "all". Especially when the NP is S or A, "all" emphasises the unity of the action, while "every" emphasises the separateness of the actions. Now of course (maybe in most cases) this dichotomy is not needed. It seems to me, that in that case, English uses "every" as the default case (the Scandinavian languages use "all" as the default ??? ). In '''béu''' the default is "all" '''ù'''. | |||

On line 9, it seems that "one" adds emphasis to the "every". Probably, not so long ago, "every" was valid by itself. The meaning of this word (in English anyway) seems particularly prone to picking up other elements (for the sake of emphasis) with a corresponding lost of power for the basic word when it occurs alone. (From Etymonline EVERY = early 13c., contraction of Old English æfre ælc "each of a group," literally "ever each" (Chaucer's everich), from each with ever added for emphasis. The word still is felt to want emphasis; as in Modern English every last ..., every single ..., etc.) | |||

.. | |||

This table is also valid for the distal determiner "that". For the third determiner ("which") the table is much truncated ... | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ... | {| | ||

|align=center| 1 | |||

|align=center| '''nò báu nái''' | |||

|align=left| which men | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 | |||

|align=center| ... '''auva báu nái''' | |||

|align=center| which two men => '''ataitauta báu nái''' which 1727 of these men | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

Below I have reproduced the above two tables for when the noun is dropped (but understood as background information). It is quite trivial to generate the below tables. Apart from lines 8 and 10, just delete "men" from the English phrase and '''báu''' from the '''béu''' phrase. (I must think about why 8 and 10 are different ???) | |||

.. | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| 1 | |||

|align=left| '''ù dí''' | |||

|align=left| all of these OR all these | |||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align= | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 2 | ||

|align= | |align=left| '''uwe dí''' | ||

|align=left| many of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 3 | ||

|align=left| '''iyo dí''' | |||

|align= | |align=left| few of these OR a few of these | ||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 4 | ||

|align= | |align=left| '''auva dí''' | ||

|align=left| 2 of these => '''ataitauta dí''' ... 1727 of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 5 | ||

|align=left| '''kyà dí''' | |||

|align=left| none of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 6 | ||

|align= | |align=left| '''í dí''' | ||

|align=left| any of these OR any one of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 7 | ||

|align=left| '''é dí''' | |||

|align= | |align=left| one of these | ||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| - 8 - | ||

|align= | |align=left| '''è dí''' | ||

|align=left| some of these OR several of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 9 | ||

|align=left| '''yú dí''' | |||

|align=left| every one of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| 10 | ||

|align=left| '''nò dí''' | |||

|align=left| these NOT several of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| | |align=center| 11 | ||

|align= | |align=left| '''é nò dí''' | ||

|align=left| one or more of these | |||

|align= | |||

|- | |- | ||

|align=center| ''' | |align=center| 12 | ||

|align= | |align=left| '''í auva dí''' ... | ||

|align=left| any 2 of these => '''í ataitauta dí''' ... any 1727 of these | |||

|} | |} | ||

.. | .. | ||

== ... | {| | ||

|align=center| 1 | |||

|align=center| '''nò nái''' | |||

|align=left| which ones | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 | |||

|align=center| ... '''auva nái''' | |||

|align=center| which two => '''ataitauta nái''' which 1727 | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

In the last section we introduced the rule, that when a determiner is the head, then the determiner changes form (an '''a''' is prefixed to it) | |||

''' | |||

Now we must introduce an exception to that rule ... when you have a specifier just to the left of a determiner (in this conjunction, the determiner MUST be the head) the determiner takes its original form. | |||

.. | .. | ||

== .. | ==== .. The emphatic particle==== | ||

.. | .. | ||

Now even before the specifiers it is possible to have an element. This is the emphatic particle '''á'''. | |||

This is also used as a sort of vocative case. Not really obligatory but used before a persons name when you are trying o get their attention. | |||

When this particle comes directly in front of '''adi''', '''ade''' and '''anai''' an amalgamation takes place ( '''á adi''' etc etc are in fact illegal) | |||

'''á adi''' => '''ádí''' = "this one!" | |||

'''á ade''' => '''ádé''' = "that one!" | |||

'''á anai''' => '''ánái''' = "which one!" | |||

These three words break the rule that only monosyllabic words can have tone. These 3 words are the only exception to that rule. | |||

By the way, emphasis is always used when contrasting two things. as in "this is wet, but that is dry" = '''ádí nucoi, ádé mideu''' | |||

When written using the '''béu''' writing system, only the initial '''a''' is given the dot on the RHS which indicates high tone. The second syllable is unmarked. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== .. | ==== .. The relative clause==== | ||

.. | .. | ||

'''béu''' relative clauses work pretty much the same as English relative clauses. | |||

'''báu à glà timpori''' = the man whom the woman hit | |||

'''báu às glà timpori''' = the man who hit the woman | |||

The relativizer is '''à''' or '''às'''. '''à''' if the NP has an S or O role within the relative clause ... '''às''' if the NP has an A role within the relative clause ... '''béu''' being an ergative language. | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== .. | === ... The uncountable noun fandauza=== | ||

.. | .. | ||

It can consist of ... (1) "the holder" ... (2) the head '''hua''' ... (3) adjectives '''saidau''' ... (4) a determiner '''didedau'''. Only the head is mandatory. | |||

'''auva hoŋko ʔazwo pona dí''' = two cups of this hot milk | |||

Note ... even though we have no word "of" ... there is no ambiguity. If the above was two '''fandaunyo''', there would either be a pause between '''hoŋko''' and '''ʔazwo''' (for example if one was A and one was the O argument), or they would be separated by "and" '''wí''' if they were separate '''fandaunyo''' but comprised only one argument. | |||

.. | In this respect '''béu''' takes after Indonesian. For example ... five big bags of this black rice = lima tas besar beras hitam ini (literally ... five bag big rice black this) | ||

Note that the "holder ???" can be a complete countable noun '''fandaunyo''' in itself. | |||

lima tas besar beras hitam ini | |||

''' | (5 bag big) (rice black this) .... Usually languages have a linker, particular when the phrases are long. For example Chinese "de", English "of", Japanese "no". '''béu''' has no linker (similar to Indonesian) ... (however '''à''' or '''fí''' could be pressed into service if needed ??? ) | ||

''' | (SideNote) ... '''ʔazwe''' = to suck ... '''ʔazweye''' = to suckle, to offer the breast | ||

.. | |||

=== ... The pronoun fandauza=== | |||

.. | .. | ||

Below the forms of the '''béu''' pronouns are the given for when the pronoun represent the S or O argument. This form can be considered the "base form" or the "unmarked form". | |||

.. | .. | ||

{| border=1 | |||

|align=center| me | |||

''' | |align=center| '''pà''' | ||

|align=center| us | |||

''' | |align=center| '''yùa''' | ||

|- | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| us | |||

|align=center| '''wìa''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| you | |||

|align=center| '''gì''' | |||

|align=center| you (plural) | |||

''' | |align=center| '''jè''' | ||

|- | |||

|align=center| him, her | |||

|align=center| '''ò''' | |||

|align=center| them | |||

|align=center| '''nù''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| it | |||

''' | |align=center| '''ʃì''' | ||

|align=center| them | |||

|align=center| '''ʃì''' | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

When they are used as an S arguments (i.e. with an intransitive verb), it might be better to translate these pronouns as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc. | |||

.. | .. | ||

There is another pronoun but this one only occurs as an O argument. When a action is performed by somebody or something on themselves we use '''tí''' to represent the O argument. | |||

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in '''béu''' we do not say '''*pás pà timpari''', but '''pás tí timpari'''. | |||

.. | .. | ||

Below is a table with '''nù''' "they" occurring with the allowed specifiers. '''yùa''', '''wìa''', '''jè''' and '''ʃì''' pattern in a similar way. | |||

''' | {| | ||

|align=center| 1 | |||

|align=center| '''í nù''' | |||

|align=left| any of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 2 | |||

|align=center| '''é nù''' | |||

|align=center| one of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 3 | |||

|align=center| '''yú nù''' | |||

|align=center| every one of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 4 | |||

|align=center| '''è nù''' | |||

|align=left| some of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 5 | |||

|align=center| '''kyà nù''' | |||

|align=center| none of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 6 | |||

|align=center| '''ù nù''' | |||

|align=center| all of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 7 | |||

|align=center| '''kyà nù''' | |||

|align=center| none of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 8 | |||

|align=center| '''í auva nù''' | |||

|align=center| any two of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 9 | |||

|align=center| '''ege nù''' | |||

|align=center| more of them | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| 10 | |||

|align=center| '''ozo nù''' | |||

|align=center| less of them | |||

|} | |||

Nothing really surprising in the above. However I thought that I should lay it out in black and white. (what about '''emo''' "the most" and '''omo''' "the least" ??) | |||

''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

Because the person and number of the A or S argument is expressed in the actual verb. The above are usually dropped (however the third person pronoun is occasionally retained to give the distinction between human and non-human subject) so when the pronouns above are come across, it might be better to translate them as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc. | |||

.. | It is a rule that '''tí''' must follow the A argument (if it is overtly expressed ... i.e. by a free-standing pronoun and not just in the verb) | ||

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in '''béu''' only one. | |||

.. | .. | ||

Below the form of the '''béu''' pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the A argument. | |||

''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

==== | {| border=1 | ||

|align=center| I | |||

|align=center| '''pás''' | |||

|align=center| we (includes "you") | |||

|align=center| '''yúas''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| | |||

|align=center| we (doesn't include "you") | |||

|align=center| '''wías''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| you | |||

|align=center| '''gís''' | |||

|align=center| you (plural) | |||

|align=center| '''jés''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| he, she | |||

|align=center| '''ós''' | |||

|align=center| they | |||

|align=center| '''nús''' | |||

|- | |||

|align=center| it | |||

|align=center| '''ʃís''' | |||

|align=center| they | |||

|align=center| '''ʃís''' | |||

|} | |||

.. | .. | ||

=== ... The sandaunyo=== | |||

.. | |||

.. | .. | ||

''' | The '''sandaunyo''' is similar to the '''fandaunyo''' but built around a '''sandau''' as opposed to a '''fandau'''. | ||

''' | '''sandau''' = a verbal noun, an infinitive, a maSdar .... whatever you want to call it. Ultimately derived from the word '''sanyo''' which means "an event". ('''fanyo''' and '''sanyo''' are equivalent to the Japanese "mono" and "koto"). The word for "verb" is '''jaudau'''. Of course there is a one to one relationship between the '''jaudau''' and the '''sandau''' (as in English if you have an infinitive verb form, you are of course going to have a corresponding finite verb form). | ||

In the '''sandaunyo''' there are fixed word orders. They are VS and VAO. If there are any adverbs or locatives they follow the S or the O. For example ... | |||

''' | |||

.. | .. | ||

= | '''somwo pà''' = "my sleep" | ||

.. | '''timpa báu glà''' = the man's hitting of the woman ... Note that '''báu''' does not have the ergative suffix -'''s''' | ||

'''solbe pà moze pona sacowe rì kéu''' = My drinking the cold water quickly was bad | |||

''' | '''timpwa glà''' = the woman being struck ... Note ... to form an passive, you infix '''w'''. | ||

'''solbwe moze rì kéu''' = The drinking of the water was bad | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ..... The '''hipeza'''== | |||

.. | .. | ||

''' | A '''hipeza''' could be translated as "infinitive phrase" | ||

''' | Now a '''hipe''' is a type of nouns. So when determiners etc. etc. are added on they must conform to the rules for regular NP's. | ||

''' | However they differ in that they never take plurals and are never possessed (that is followed by '''yú''' ). | ||

''' | A '''hipeza''' is any phrase with a '''hipe''' at its heart. | ||

Now on occasion S, O and A arguments must appear in a '''hipeza'''. | |||

'''béu''' is quite strict on how these arguments can be added. | |||

They must all follow the infinitive. | |||

1) If in the indicative or subjunctive, an argument takes the ergative affix '''s''', in the infinitive, while having no affix, must be preceded by '''hí'''. | |||

2) The O argument always comes before the A argument. | |||

3) Other argument relating to time, place and manner come after the S, O and A arguments. | |||

---------- | |||

English has quite a number of different ways of including S, O and A arguments with the infinitive. See below ... | |||

1) Attila's destruction of Rome | |||

2) Rome's destruction (by Attila) | |||

3) The destruction of Rome (by Attila) | |||

----- | |||

Tie in the participle phrase (equivalent to Dixon's complement clause) ??? | |||

.. | .. | ||

== ..... Arithmetic== | |||

.. | .. | ||

'''noiga''' = arithmetic | |||

[[Image:TW_215.png]] | |||

In the above table you can see how the symbol for the numbers 1 to 11 are derived. In the first column are how the numbers are pronounced in '''béu'''. In the second column is the symbol used for the single consonant which exists in the heart of every number. In the third column you can see how this consonant is modified slightly to produce the symbol used for each number. All these number symbols have a "number bar" extending from the top of the symbol towards the right. Only the first number in a string will have this "number bar". | |||

.. | On the left you can see how the symbols for the numbers -1 to -11 are derived. As you can see for the negative numbers there is a number bar extending from from the top of the symbol towards the left. | ||

Notice that the forms for 1, 6, 7 and 9 have been modified slightly before the "number bar" has been added. | |||

[[Image:TW_216.png]] | |||

Above you can see some interesting symbols. These are used to extend the range of the '''béu''' number system (remember the basic system only covers 1-> 1727). | |||

Also there are to special symbols that mean "exactly" and "approximately" these are often appended to a number string. | |||

To | To give you an idea of how they are used, I have given you a very big number below. | ||

. | [[Image:TW_214.png]] | ||

'''aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dù''' | |||

.. | Which is => 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... E represents eleven and T represents ten ... remember the number is in base 12. | ||

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only ... if you can handle this number you can handle any number. | |||

Now the 7 "placeholders"<sup>*</sup> are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. Used in the same way that we would say "point" or "decimal" when reeling off a number. | |||

.. | One further point of note ... | ||

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say '''auvaidaula nàin''' .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. | |||

However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say '''yanfa elaibau''' .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630 volts" instead of "630 microvolts". | |||

. | [[Image:TW_211.png]] | ||

In the table above is shown the method for writing imaginary numbers and fractions. | |||

Also the method of laying out the 4 basic arithmetic operations are shown. | |||

A number can be made imaginary by adding a further stroke that touches the "number bar". And to get a fraction, you add a stroke just above the number. This stroke looks a bit like a small "8" on its side. | |||

Notice that there is a special sign to indicate addition ('''+'''), and also a special sign for equality ('''=>'''). | |||

.. | As you can see above, there is no special sign for the multiplication or division operation. The numbers are simply written one beside the other. | ||

Division is the same as multiplication except that the denominator is in "fractional form". | |||

.. | -6 is pronounced '''komo ela''' ... '''komo''' meaning left or negative. | ||

By the way '''bene''' means right (as in right-hand-side) or positive. | |||

.. | 4i is pronounced '''uga haspia'''<sup>**</sup> ... and what does '''haspia''' mean, well it is the name of the little squiggle that touches the number bar, for one thing. | ||

-4i is pronounced '''komo uga haspia''' | |||

-1/10 is pronounced '''komo diapa''' | |||

i/4 is pronounced '''duga haspia''' | |||

.. | <sup>*</sup>Actually these placeholder symbols are named after 6 living things. This does not lead to confusion tho'. When you are doing arithmetic these concrete meanings are totally bleached. | ||

<sup>**</sup>This can also be pronounced as '''bene uga haspia'''. However usually the '''bene''' bit is deemed redundent. | |||

.. | .. | ||

== | == ... Index== | ||

{{Béu Index}} | {{Béu Index}} | ||

Revision as of 01:11, 12 January 2015

..... Some fundamentals of the grammar

..

This is an ergative language. The ergative marker is -s or -os ? for words ending in a vowel or sá for a multi-word NP.

In the main clause there is free word order. That is, you can have SV, VS, AVO, AOV, VAO, OVA, OAV or VOA*

The choices VAO/VOA and AOV/OAV are made on discourse grounds.

The other choices are made according to the definiteness of the S, A and O arguments.

If definite they come before the verb, if not they come after.

Note ... é and è also code for indefiniteness ... OK they are useful for oblique NP and subclauses ... when they appear with S, A or O arguments in a main clauses they impart the notion that the argument is unknown to the speaker as well (or at least that the speaker has limited interest in the argument).

* Actually in a piece of discourse, it is most likely that the S or A argument are old information and probably the topic. When this is the case they are dropped and instead of the 8 sentence types shown above, we have only the 3 sentence types, V(s), O V(a) and V(a) O where V(s) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the S argument and V(a) represents a verb marked for the person/number of the A argument.

..... Noun phrases

..

There are 4 types of noun phrase in béu ...

..

1) The noun phrase for countable nouns

2) The noun phrase for uncountable nouns

3) The noun phrase for pronouns

4) The noun phrase for verbs

5) The noun phrase for places

..

From now on I will not be talking about "noun phrase", but will be using the béu term fandaunyo.

fandau = noun*

fandauza** = "a noun phrase"

fandaunyo*** = "a noun or a noun phrase"

*The usual word building process would give fanyədau (from nandau "word" and fanyo "thing/object"). However in this particular word, there has been a further contraction to fandau.

** the suffix -za, is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word".

*** the suffix -nyo, is a suffix used to give the meaning "something more complicated than the basic word OR the basic word.

..

... The countable nouns fandauza

..

It can consist of ... (1) the emphatic particle ... (2) a specifier koiʒi ... (3) a number ... (4) the head hua ... (5) adjectives saidau ... (6) a determiner ... (7) a question word ... (8) a relative clause. Only the head is mandatory.

Actually there are quite a few restrictions. For example (7) would never occurs with (8) .... mmmh why did I insert "would" here ??

Many restrictions between (2) and (3)

..

.. The question words

..

The set of possible question word (within a NP) is very small. Only three ... nái "which", láu "how much" or "how many", kái "what kind of".

..

.. The determiners

..

The set of possible determiners is very small. Only two ... dí "this", or dè "that".

..

.. The adjectives

..

Not much to say about this one, you can string together as many as you like ... the same as in English. Also genitives are put in this slot. A genitive is a word derived from a noun by the suffixing of -n (or -on) which indicates possession*. Genitives always come after the regular adjective.

*Actually it can also stand for a location ... where the NP is at.

..

.. The head

..

This is usually a noun. However it can also be an adjective. When it is an adjective it has concrete reference instead of representing a quality (as happens often in English). For instance, when talking about ... say ... a photograph, you could say "the green is too dark". In this sentence "the green" is a NP meaning the quality of being green. In béu if green is used as the head of a NP it always means "the green one" : "the person/thing that is green".

In béu, geunai would be used in a sentence such as "the green is too dark".

gèu = "green" or "the green one"

geumai = "greenness"

saco = "slow" or "the slow one"

saconi = "slowness"

Notice that the suffix has two forms ... depending upon whether the base adjective has one syllable or more than one syllable.

Sometimes the head is a determiner. In these cases the NP is understood to refer to some noun ... but it is not spoken ... it is just understood by all parties. In these cases the determiners undergo a change of form ...

dí => adi = "this one"

dè => ade = "that one"

nái => anai = "which one"

Related to dí and dè are the two nouns dían (here) and dèn (there). Although nouns, they never occur with the locative case or the ergative case.

..

.. The specifiers

..

The specifiers = nandau.a koiʒi or just koiʒia

koiʒi actually means "preface" as in "the preface to the book"

It also means forewarning or harbinger ... as in "that slight tremor on Tuesday night, was koizi of the quake on Friday"

Immediately before the core you can have a specifier.

There consist of the following ...

..

kyà = no, í = any, é = some(for singular noun), yú = every, è = some(for plural nouns), nò = plural, ù = all, auva => ataitauta = 2=>1727, uwe = many, iyo = few, ege = more, ozo = less.

..

Notice that the specifier that implies zero number has low tone, the 3 specifiers that imply singular* number have high tone and the 3 specifiers that imply plural* number have low tone.

.* Well this is true for the English translations anyway. (Side Note ... Actually I am not so sure about the "logic" of my little scheme. Also I would like to look into how a spectrum of other languages use specifiers)

Also note that nò is a noun (meaning "number") as well as a particle that denotes plurality. In the béu mathematical tradition, nò means a number from 2 -> 1727 only (of course there are expressions for expanding the concept to integers, rational numbers etc. etc.)

After a koiʒi the head is always in its base form with regard to number. For example ...

..

é glà = some woman

è glà = some women ... not *è gala

í toti = any child .......... not *í totai

..

The are 4 cases where you can have two koiʒi together ... é nò or when you have í followed by a number greater than one. For example ...

..

é nò toti = some child or children ... this is a contraction of "é toto OR nò toti"

í auva toti = any two children

ege auva toti = two more children

ozo auva toti = two less children

..

.. Specifiers X determiners

..

Below is a table showing all the specifiers plus a countable noun plus the proximal determiner "this".

..

| 1 | ù báu dí | all of these men OR all these men |

| 2 | uwe báu dí | many of these men |

| 3 | iyo báu dí | few of these men OR a few of these men |

| 4 | auva báu dí | two of these men => ataitauta báu dí ... 1727 of these men |

| 5 | kyà báu dí | none of these men |

| 6 | í báu dí | any of these men OR any one of these men |

| 7 | é báu dí | one of these men |

| - 8 - | è báu dí | some of these men |

| 9 | yú báu dí | every one of these men |

| 10 | nò báu dí | several of these men OR several of these men here |

| 11 | é nò báu dí | one or more of these men |

| 12 | í auva báu dí ... | any 2 of these men => í ataitauta báu dí ... any 1727 of these men |

..

The above table is worth discussing ... for what it tells us about English as much as anything else.

..

One line 1 ... I do not know why "all these men" is acceptable ... on every other line "of" is needed (to think about)

Similarly on line 3 ... I do not know why "a few" is a valid alternative.

Notice that *aja báu dí does not exist. It is illegal. "one of these men" is expressed on line 7. aja only used in counting ???

I should think more on the semantic difference between line 10 and line 8. ???

line 1 and line 9 are interesting. Every language has a word corresponding to "every" (or "each", same same) and a word corresponding to "all". Especially when the NP is S or A, "all" emphasises the unity of the action, while "every" emphasises the separateness of the actions. Now of course (maybe in most cases) this dichotomy is not needed. It seems to me, that in that case, English uses "every" as the default case (the Scandinavian languages use "all" as the default ??? ). In béu the default is "all" ù.

On line 9, it seems that "one" adds emphasis to the "every". Probably, not so long ago, "every" was valid by itself. The meaning of this word (in English anyway) seems particularly prone to picking up other elements (for the sake of emphasis) with a corresponding lost of power for the basic word when it occurs alone. (From Etymonline EVERY = early 13c., contraction of Old English æfre ælc "each of a group," literally "ever each" (Chaucer's everich), from each with ever added for emphasis. The word still is felt to want emphasis; as in Modern English every last ..., every single ..., etc.)

..

This table is also valid for the distal determiner "that". For the third determiner ("which") the table is much truncated ...

..

| 1 | nò báu nái | which men |

| 2 | ... auva báu nái | which two men => ataitauta báu nái which 1727 of these men |

..

Below I have reproduced the above two tables for when the noun is dropped (but understood as background information). It is quite trivial to generate the below tables. Apart from lines 8 and 10, just delete "men" from the English phrase and báu from the béu phrase. (I must think about why 8 and 10 are different ???)

..

| 1 | ù dí | all of these OR all these |

| 2 | uwe dí | many of these |

| 3 | iyo dí | few of these OR a few of these |

| 4 | auva dí | 2 of these => ataitauta dí ... 1727 of these |

| 5 | kyà dí | none of these |

| 6 | í dí | any of these OR any one of these |

| 7 | é dí | one of these |

| - 8 - | è dí | some of these OR several of these |

| 9 | yú dí | every one of these |

| 10 | nò dí | these NOT several of these |

| 11 | é nò dí | one or more of these |

| 12 | í auva dí ... | any 2 of these => í ataitauta dí ... any 1727 of these |

..

| 1 | nò nái | which ones |

| 2 | ... auva nái | which two => ataitauta nái which 1727 |

..

In the last section we introduced the rule, that when a determiner is the head, then the determiner changes form (an a is prefixed to it)

Now we must introduce an exception to that rule ... when you have a specifier just to the left of a determiner (in this conjunction, the determiner MUST be the head) the determiner takes its original form.

..

.. The emphatic particle

..

Now even before the specifiers it is possible to have an element. This is the emphatic particle á.

This is also used as a sort of vocative case. Not really obligatory but used before a persons name when you are trying o get their attention.

When this particle comes directly in front of adi, ade and anai an amalgamation takes place ( á adi etc etc are in fact illegal)

á adi => ádí = "this one!"

á ade => ádé = "that one!"

á anai => ánái = "which one!"

These three words break the rule that only monosyllabic words can have tone. These 3 words are the only exception to that rule.

By the way, emphasis is always used when contrasting two things. as in "this is wet, but that is dry" = ádí nucoi, ádé mideu

When written using the béu writing system, only the initial a is given the dot on the RHS which indicates high tone. The second syllable is unmarked.

..

.. The relative clause

..

béu relative clauses work pretty much the same as English relative clauses.

báu à glà timpori = the man whom the woman hit

báu às glà timpori = the man who hit the woman

The relativizer is à or às. à if the NP has an S or O role within the relative clause ... às if the NP has an A role within the relative clause ... béu being an ergative language.

..

... The uncountable noun fandauza

..

It can consist of ... (1) "the holder" ... (2) the head hua ... (3) adjectives saidau ... (4) a determiner didedau. Only the head is mandatory.

auva hoŋko ʔazwo pona dí = two cups of this hot milk

Note ... even though we have no word "of" ... there is no ambiguity. If the above was two fandaunyo, there would either be a pause between hoŋko and ʔazwo (for example if one was A and one was the O argument), or they would be separated by "and" wí if they were separate fandaunyo but comprised only one argument.

In this respect béu takes after Indonesian. For example ... five big bags of this black rice = lima tas besar beras hitam ini (literally ... five bag big rice black this)

Note that the "holder ???" can be a complete countable noun fandaunyo in itself.

lima tas besar beras hitam ini

(5 bag big) (rice black this) .... Usually languages have a linker, particular when the phrases are long. For example Chinese "de", English "of", Japanese "no". béu has no linker (similar to Indonesian) ... (however à or fí could be pressed into service if needed ??? )

(SideNote) ... ʔazwe = to suck ... ʔazweye = to suckle, to offer the breast

..

... The pronoun fandauza

..

Below the forms of the béu pronouns are the given for when the pronoun represent the S or O argument. This form can be considered the "base form" or the "unmarked form".

..

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

When they are used as an S arguments (i.e. with an intransitive verb), it might be better to translate these pronouns as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

..

There is another pronoun but this one only occurs as an O argument. When a action is performed by somebody or something on themselves we use tí to represent the O argument.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in béu we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari. ..

Below is a table with nù "they" occurring with the allowed specifiers. yùa, wìa, jè and ʃì pattern in a similar way.

| 1 | í nù | any of them |

| 2 | é nù | one of them |

| 3 | yú nù | every one of them |

| 4 | è nù | some of them |

| 5 | kyà nù | none of them |

| 6 | ù nù | all of them |

| 7 | kyà nù | none of them |

| 8 | í auva nù | any two of them |

| 9 | ege nù | more of them |

| 10 | ozo nù | less of them |

Nothing really surprising in the above. However I thought that I should lay it out in black and white. (what about emo "the most" and omo "the least" ??)

..

Because the person and number of the A or S argument is expressed in the actual verb. The above are usually dropped (however the third person pronoun is occasionally retained to give the distinction between human and non-human subject) so when the pronouns above are come across, it might be better to translate them as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

It is a rule that tí must follow the A argument (if it is overtly expressed ... i.e. by a free-standing pronoun and not just in the verb)

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

..

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the A argument.

..

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

..

... The sandaunyo

..

The sandaunyo is similar to the fandaunyo but built around a sandau as opposed to a fandau.

sandau = a verbal noun, an infinitive, a maSdar .... whatever you want to call it. Ultimately derived from the word sanyo which means "an event". (fanyo and sanyo are equivalent to the Japanese "mono" and "koto"). The word for "verb" is jaudau. Of course there is a one to one relationship between the jaudau and the sandau (as in English if you have an infinitive verb form, you are of course going to have a corresponding finite verb form).

In the sandaunyo there are fixed word orders. They are VS and VAO. If there are any adverbs or locatives they follow the S or the O. For example ...

..

somwo pà = "my sleep"

timpa báu glà = the man's hitting of the woman ... Note that báu does not have the ergative suffix -s

solbe pà moze pona sacowe rì kéu = My drinking the cold water quickly was bad

timpwa glà = the woman being struck ... Note ... to form an passive, you infix w.

solbwe moze rì kéu = The drinking of the water was bad

..

..... The hipeza

..

A hipeza could be translated as "infinitive phrase"

Now a hipe is a type of nouns. So when determiners etc. etc. are added on they must conform to the rules for regular NP's.

However they differ in that they never take plurals and are never possessed (that is followed by yú ).

A hipeza is any phrase with a hipe at its heart.

Now on occasion S, O and A arguments must appear in a hipeza.

béu is quite strict on how these arguments can be added.

They must all follow the infinitive.

1) If in the indicative or subjunctive, an argument takes the ergative affix s, in the infinitive, while having no affix, must be preceded by hí.

2) The O argument always comes before the A argument.

3) Other argument relating to time, place and manner come after the S, O and A arguments.

English has quite a number of different ways of including S, O and A arguments with the infinitive. See below ...

1) Attila's destruction of Rome

2) Rome's destruction (by Attila)

3) The destruction of Rome (by Attila)

Tie in the participle phrase (equivalent to Dixon's complement clause) ???

..

..... Arithmetic

..

noiga = arithmetic

In the above table you can see how the symbol for the numbers 1 to 11 are derived. In the first column are how the numbers are pronounced in béu. In the second column is the symbol used for the single consonant which exists in the heart of every number. In the third column you can see how this consonant is modified slightly to produce the symbol used for each number. All these number symbols have a "number bar" extending from the top of the symbol towards the right. Only the first number in a string will have this "number bar".

On the left you can see how the symbols for the numbers -1 to -11 are derived. As you can see for the negative numbers there is a number bar extending from from the top of the symbol towards the left.

Notice that the forms for 1, 6, 7 and 9 have been modified slightly before the "number bar" has been added.

Above you can see some interesting symbols. These are used to extend the range of the béu number system (remember the basic system only covers 1-> 1727).

Also there are to special symbols that mean "exactly" and "approximately" these are often appended to a number string.

To give you an idea of how they are used, I have given you a very big number below.

aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dù

Which is => 1,206,8E3,051.58T,630,559,62 ... E represents eleven and T represents ten ... remember the number is in base 12.

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only ... if you can handle this number you can handle any number.

Now the 7 "placeholders"* are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. Used in the same way that we would say "point" or "decimal" when reeling off a number.

One further point of note ...

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say auvaidaula nàin .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say yanfa elaibau .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630 volts" instead of "630 microvolts".

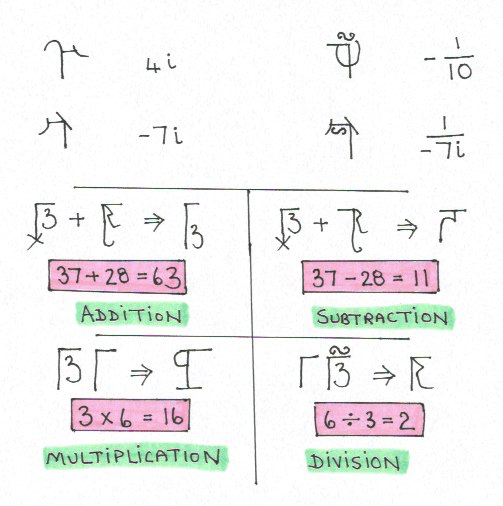

In the table above is shown the method for writing imaginary numbers and fractions.

Also the method of laying out the 4 basic arithmetic operations are shown.

A number can be made imaginary by adding a further stroke that touches the "number bar". And to get a fraction, you add a stroke just above the number. This stroke looks a bit like a small "8" on its side.

Notice that there is a special sign to indicate addition (+), and also a special sign for equality (=>).

As you can see above, there is no special sign for the multiplication or division operation. The numbers are simply written one beside the other.

Division is the same as multiplication except that the denominator is in "fractional form".

-6 is pronounced komo ela ... komo meaning left or negative.

By the way bene means right (as in right-hand-side) or positive.

4i is pronounced uga haspia** ... and what does haspia mean, well it is the name of the little squiggle that touches the number bar, for one thing.

-4i is pronounced komo uga haspia

-1/10 is pronounced komo diapa

i/4 is pronounced duga haspia

*Actually these placeholder symbols are named after 6 living things. This does not lead to confusion tho'. When you are doing arithmetic these concrete meanings are totally bleached.

**This can also be pronounced as bene uga haspia. However usually the bene bit is deemed redundent.

..

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences