Béu : Stuff discarded after 28th Mar 2013: Difference between revisions

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

Stuff discarded after 28th Mar 2013 is in this chapter. | Stuff discarded after 28th Mar 2013 is in this chapter. | ||

== ...... From the indicative verb form paradign== | |||

3) Then one of the 16 markers below are added. These show tense and aspect. | |||

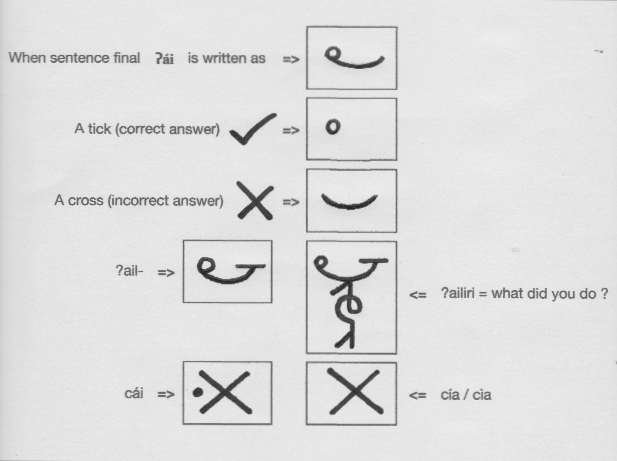

[[Image:TW_303.png]] | |||

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above. | |||

Looking at the above table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... '''i''' for the past, '''a''' for the present and '''u''' for the future. The final column (highlighted in orange) markers have a timeless meaning. | |||

'''-ri''' ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense. | |||

'''-ra''' ... Should only be used if the action is happening at the moment of speaking. For example ... '''doikara''' = I am walking | |||

Note ... If you say in '''béu''' "walking five hours" it means "walking for five hours already (and still walking). | |||

'''-ru''' ... This is the future tense. | |||

'''-r''' ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly". | |||

The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school). In English the timeless habitual is expressed periphrastically (i.e. I usually go to school). | |||

Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). This also happens in '''béu''' i.e. we would say '''doikar''' in the expression "I walk to school every day". '''doikarna''' would be used only if we were going on to mention some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift in his new car) . | |||

So '''doikarno''' means "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use '''doikar''' | |||

'''-rnu''' ... This is the future habitual. English doesn't have a future habitual. In what situations would this be used ?. Well suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In '''béu''' you would answer '''doikarnu'''. | |||

The next row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2. | |||

'''doikorji''' => He/she didn't walk ... '''doikorjo''' => He/she doesn't walk ... '''doikorju''' => He/she will not walk | |||

To express the fact that he isn't walking at this moment, we would say '''ki doikorjo ''' where '''ki''' = now | |||

In a similar way we can make up a habitual present tense ... '''ki doikorno''' = nowadays I usually walk .... (Note ... these two constructions fill in the two blanks in the table) | |||

The next row gives the perfect tense. | |||

'''doikorwi''' = He/she had walked ... '''doikorwa''' = He/she has walked ... '''doikorwu''' = He/she will have walked | |||

The next tense is a kind of negative of the perfect tense, as it implies that something has not happened up to the present time. It is only used when there is still hope of the event occurring ; if there is no hope, the past tense is used. For example ... | |||

'''jono dorwa ʔé''' = Has John come? If the answer is no but there is still a good possibility that he will arrive the answer will be '''dorya''' ... but if the time of his coming is now past, the answer would be, '''dorji'''. | |||

'''doikoryi''' = He/she had not walked yet ... '''doikorya''' = He/she hasn't walked yet ... '''doikoryu''' = He/she will not have walked yet | |||

Another use of -'''rw''' is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example '''larwa london''' = I have been to London ... sometimes called the "experiential aspect" | |||

When -'''rw''' is used in this way, you negate the sentence by introducing the particle '''uku''' (never) instead of using the -'''ry''' form. For example ... | |||

'''lirwa london ʔé''' = Have you been to London ...... '''larwa london''' = I have been to London ..... '''uku larwa london''' = I have never been to London | |||

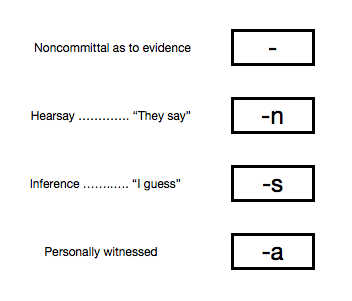

4) And finally one of these 4 evidential markers are added ... ∅ -'''n''' -'''s''' -'''a''' | |||

[[Image:TW_122.png]] | |||

About a quarter of the worlds languages have what is called "evidentiality" expressed in the verb. However as evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has evidentials you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. | |||

The first one is -∅ (a zero suffix). This one gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based. For example ... | |||

'''doikori''' = He/she walked | |||

The second one is -'''n'''. In this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so. For example ... | |||

'''doikorin''' = They say he/she walked | |||

The third one is -'''s'''. In this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow. For example ... | |||

'''doikoris''' = I guess he walked | |||

The third one is -'''a'''. In this case the speaker saw the action with his own eyes*. For example ... | |||

'''doikoria''' = I saw him walk | |||

The last evidential marker is limited in its distribution. It can only be used with the past tense form '''i'''. | |||

The second and third evidentials introduce some doubt. The fourth on the contrary introduces more certainty. | |||

An '''o''' is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s". | |||

.* This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself". | |||

Addendum | |||

There are two adverbs '''màs''' and '''lói'''. | |||

As with all adverbs they can be placed almost anywhere in a sentence. However these two have a strong preference to be sentence initial. | |||

'''màs solbori''' = maybe he drank | |||

'''lói solbori''' = probably he drank | |||

You could say that the first one indicates about 50 % certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty. | |||

These two adverbs can only occur with the zero suffix evidential. | |||

== ...... Possessive Pronouns== | == ...... Possessive Pronouns== | ||

Revision as of 03:36, 5 December 2014

..... Note .....

Stuff discarded before 28th Mar 2013 is in chapter XX

Stuff discarded after 28th Mar 2013 is in this chapter.

...... From the indicative verb form paradign

3) Then one of the 16 markers below are added. These show tense and aspect.

The items below the solid line are the negatives of the items above.

Looking at the above table, you can see the first 3 columns differ by their vowel. These are the tenses ... i for the past, a for the present and u for the future. The final column (highlighted in orange) markers have a timeless meaning.

-ri ... This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

-ra ... Should only be used if the action is happening at the moment of speaking. For example ... doikara = I am walking

Note ... If you say in béu "walking five hours" it means "walking for five hours already (and still walking).

-ru ... This is the future tense.

-r ... This has no time reference. It might be used for timeless "truths" such as "the sun rises in the West" or "birds fly".

The next row has what is called the habitual aspect. English has a past habitual (i.e. I used to go to school). In English the timeless habitual is expressed periphrastically (i.e. I usually go to school).

Often in English the plain form of the verb is used as a habitual (i.e. I drink beer). This also happens in béu i.e. we would say doikar in the expression "I walk to school every day". doikarna would be used only if we were going on to mention some exception (i.e. but last tuesday Allen gave me a lift in his new car) .

So doikarno means "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or "I usually walk". If you walked on every occasion that was possible, then you would use doikar

-rnu ... This is the future habitual. English doesn't have a future habitual. In what situations would this be used ?. Well suppose you have just moved to a new house and are asked "how will you get to the supermarket". In béu you would answer doikarnu.

The next row gives the negatives of row 1 and row 2.

doikorji => He/she didn't walk ... doikorjo => He/she doesn't walk ... doikorju => He/she will not walk

To express the fact that he isn't walking at this moment, we would say ki doikorjo where ki = now

In a similar way we can make up a habitual present tense ... ki doikorno = nowadays I usually walk .... (Note ... these two constructions fill in the two blanks in the table)

The next row gives the perfect tense.

doikorwi = He/she had walked ... doikorwa = He/she has walked ... doikorwu = He/she will have walked

The next tense is a kind of negative of the perfect tense, as it implies that something has not happened up to the present time. It is only used when there is still hope of the event occurring ; if there is no hope, the past tense is used. For example ...

jono dorwa ʔé = Has John come? If the answer is no but there is still a good possibility that he will arrive the answer will be dorya ... but if the time of his coming is now past, the answer would be, dorji.

doikoryi = He/she had not walked yet ... doikorya = He/she hasn't walked yet ... doikoryu = He/she will not have walked yet

Another use of -rw is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example larwa london = I have been to London ... sometimes called the "experiential aspect"

When -rw is used in this way, you negate the sentence by introducing the particle uku (never) instead of using the -ry form. For example ...

lirwa london ʔé = Have you been to London ...... larwa london = I have been to London ..... uku larwa london = I have never been to London

4) And finally one of these 4 evidential markers are added ... ∅ -n -s -a

About a quarter of the worlds languages have what is called "evidentiality" expressed in the verb. However as evidentials don't feature in any of the languages of Europe most people have never heard of them. In a language that has evidentials you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying.

The first one is -∅ (a zero suffix). This one gives no information whatsoever as to what evidence the statement is based. For example ...

doikori = He/she walked

The second one is -n. In this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so. For example ...

doikorin = They say he/she walked

The third one is -s. In this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow. For example ...

doikoris = I guess he walked

The third one is -a. In this case the speaker saw the action with his own eyes*. For example ...

doikoria = I saw him walk

The last evidential marker is limited in its distribution. It can only be used with the past tense form i.

The second and third evidentials introduce some doubt. The fourth on the contrary introduces more certainty.

An o is used to connect word final '"r" to the evidential markers "n" and "s".

.* This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself".

Addendum

There are two adverbs màs and lói.

As with all adverbs they can be placed almost anywhere in a sentence. However these two have a strong preference to be sentence initial.

màs solbori = maybe he drank

lói solbori = probably he drank

You could say that the first one indicates about 50 % certainty while the second indicates around 90 % certainty.

These two adverbs can only occur with the zero suffix evidential.

...... Possessive Pronouns

..

The possessive form of these pronouns are ...

..

| my | pàn | our | yùan |

| our | wìan | ||

| your | gìn | your (plural) | jèn |

| his, her | òn | their | nùn |

| its | ʃìn | their | ʃìn |

..

And we also have tín which is used if the possessor is the same as the subject of the clause.

Actually the n suffix is the locative. In the grammar, location and possession are marked identically.

This is similar to Scotch Gaelic. Consider Scotch Gaelic ... "Taigh agam" = "My house" (lit. "A house at me") *

Basically if n is appended to a noun that refers to a person, then the n indicates possession.

And if n is appended to a noun that refers to a place, then the n indicates location.

Sometimes the same affix can be used twice on the same word. For example cavia is a male first name.

Now in the béu lands it is quite common for small eateries and drinking establishments to be named after their owner, so cavian is, in the first instance an adjective meaning "belonging to cavia ". But in the second instance it can be a noun meaning "the place of cavia ". Then to indicate "at the place of cavia " you would have the word cavianon.**

*And in a similar way to Gaelic, béu has no possessive verb (i.e. it has no verb "to have")

Compare Gaelic ... "Tha taigh agam" — "I have a house" (lit. "A house is at me")

and béu ... twor nambo pàn — "I have a house" (lit. "Exists a house at me" or "There exists a house at me")

** Note the linking vowel o between the two n's. béu uses o as a linking vowel for nouns and e as a linking vowel for verbs.

..

..... How to ask a content question

..

English is quite typical of languages in general and has 7 content question words ... "which", "what", "who", "where", "when", "how" and "why".

A corresponding set of béu question words are given below.

..

| what | nén nós |

| who | mín mís món |

| when | kyú |

| where | dwí |

| how | fáu |

| why | mái |

| how much | linai |

| how many | nonai |

| what type of | kainai |

..

In English as in about 1/3 of the languages of the world it is necessary to front the content question word.

In béu these words are usually also fronted. They must come before the verb anyway. If they come after the verb, they mean "somebody/something", "somewhere" etc. etc.

The pilana are added to the content question words as they would be to a normal noun phrase.

Here are some examples of content questions ...

Statement 1) báus glaye kyori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Question 2) mines glaye kyori alha = who gave flowers to the woman

Question 3) báus minye kyori alha = to whom did the man gave flowers

Question 4) báus glaye fái kyori = what did the man give to the woman

lí = amount

nò = number

5) báus ye fái gla ? kyori alha = to which woman did the man give the flowers

6) báus kyori ye á gla alha = the man gave flowers to some woman

7) báus kyori ye gla alha = the man gave flowers to a woman

..

ME-form of the verb and the MI-form of a verb

These tenses are often called the 'conditional', that is, they express a supposition depending on a certain condition. When referring to present time the ME-form is used ; when referring to past time and the condition has no chance of now being realised the MI-form is used.

if knowame to read buyame book => If I knew how to read I would buy a book.

if knowami to read buyami book => If I had known how to read I would have bought a book.

..... The 15 "specified"

‘I don’t know who/what/where/when/why/how etc.’, ‘who/what etc. you want/please’, ‘who/what etc. it may be’, and ‘it does not matter who/what etc.’. The following are usually called pronouns in the Western linguistic tradition.

In Old Norse, there is a rare free-choice indefinite pronoun velhverr ‘whosoever, everyone’, which consists of interrogative hverr plus a prefixed element vel-.

Old English has similar-looking indefinite forms in the series wel-hwá, wel- hwæt, (ge-)wel-hwær, (ge-)wel-hwilc ‘any/every-one, -thing, -where, any/every’, used as follows:

The fact that Swedish, Danish and Norwegian are historically related languages adds a further dimension to the contrastive perspective. The existential determiners någon (Swedish), nogen (Danish) and noen (Norwegian) clearly have a common origin in Old Norse, eventually going back to the unattested *ne wait ek hwariR, meaning ‘I don’t know which’.

Called the 15 specifyu in the béu linguistic tradition ????

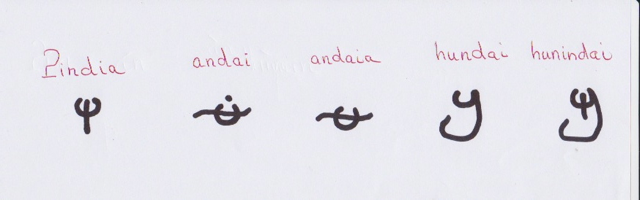

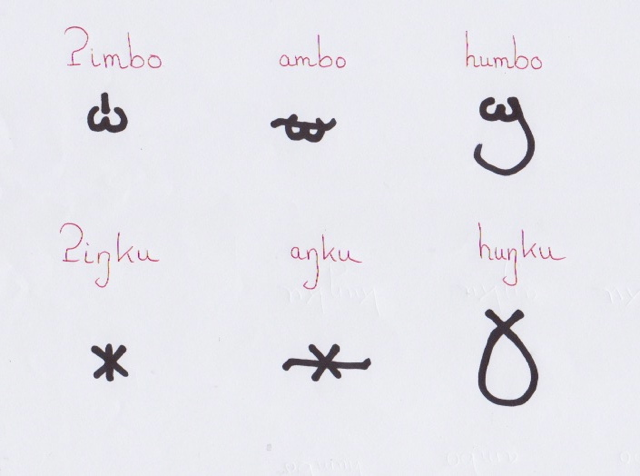

| anything | ʔindai | "something" | andai | "somethings" | andaia | everything, all | hundai | every single thing | hunindai |

The above 5 words have a special "shorthand" form. These are given below.

| anybody | ʔín | somebody | án | some people | àn | all | hùn | every single person | hunin |

The above 5 words have special "shorthand" forms. These were given in the previous section.

| anywhere | ʔimbo | somewhere | ambo | everywhere | humbo |

| ever | ʔiŋku | sometime(s) | aŋku | always | huŋku |

The above 6 words have a special "shorthand" form. These are given below.

These words are obviously have their origins in a fusion of the "specifiers" and the three word below.

bwò = place

kyú = occasion

dái = thing

A word of warning about translating from béu to English ...

As the simple specifier, when they occur alone, always have human reference, you can not say something like ...

"Italian cars are very stylish but some are prone to rusting"

If you translated this directly to béu the "some" would mean "somebody", instead you have to say ...

"Italian cars are very stylish but some of them are prone to rusting"

"some of them" = àn ʃí

"Indian women are pretty but some get fat with time"

Here again, "some" can not be used alone and would be replaced by "some of them" = àn ù

And by the way "one of them" = án ʃí or án ú. Never * aja ʃí or * aja ú

Note that béu pronouns act the sane as nouns when it comes to "specifiers".

So in the same manner as you say "some house", you say "some us" or "some them" (i.e. not some of us, or some of them)

Note that béu does not have any words corresponding to "nobody", "nothing", "never" etc. etc. To translate a sentence from English which contained these words, you would use the ʔín equivalent and negate the main verb of the clause (as you can also do in English ... "I have never gone to London" => "I haven't ever gone to London")

hunde = ever

huninde = every single day

..... Question

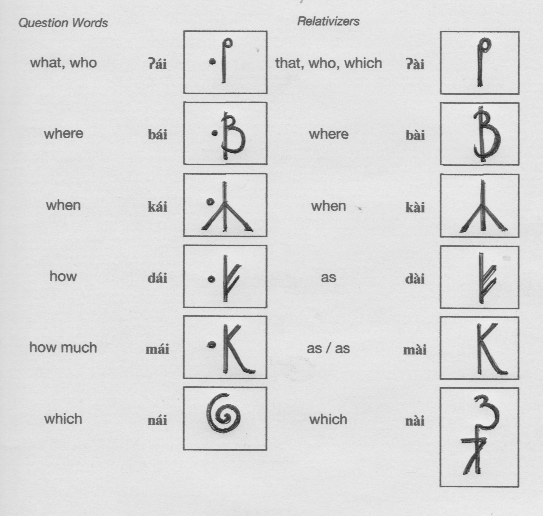

béu has a "toolbox" that allows us to ask questions. The tools in that tool box are ʔái, bái, kái, dái, mái, nái and cái ... the seven words used for asking questions.

..... The ʔainandaua or the Question Words

The table below shows some of the béu ʔainandaua

| what, who | ʔái |

| where | bái |

| when | kái |

| how | dái |

| how much | mái |

"what/who" asks the interlocutor to give an argument for the clause given.

"where" asks the interlocutor to give a place for the clause given.

"when" asks the interlocutor to give a time for the clause given.

"how" asks the interlocutor to give an adverb for the clause given.

mái is slightly different ...

if placed in front of a noun, it asks the interlocutor to give a number if the noun is countable, if not countable it is asking for an amount.

if placed in front of an adjective, it asks the interlocutor to give the degree/level of the adjective (an amount ?? should we use the same grades for nouns and adjectives ??).

These words have to be fronted (as in English). That is they must come sentence initial.

ʔái takes pilana, just as a normal noun does. Here are some examples ...

Statement ... báus glaye kyori alha = the man gave flowers to the woman

Question 1) ʔáis glaye kyori alha = who gave flowers to the woman

Question 2) ʔaiye báus kyori alhai = to whom did the man gave flowers

Question 3) ʔái báus glaye kyori = what did the man give to the woman

Notice that in 1, ʔáis is interpreted as "who" because it is overwhelmingly the case that a person would be giving flowers to somebody.

Similarly for 2, and in 3, ʔái is interpreted as "what" because it is overwhelmingly the case that a person would be giving an nonhuman object to somebody else.

By the way "why" is translated as ʔaiji "for what".

In English it is not wrong to say "what man gave the woman flowers" rather than "which man gave the woman flowers".

In béu "what" can never be conjoined with a noun as is possible in English.

In English it is not TOTALLY wrong to say "which gave the woman flowers" rather than "which man gave the woman flowers".

In béu "which" must always be conjoined with a suitable noun or pronoun.

The word for "which" is nái and it always comes after the noun that it is conjoined with. No fronting is required for nái.

For example ....

Question 4) báus nái glaye kyori alha= which man gave flowers to the woman

Question 5) báus yè glà nái kyori alha= to which woman did the man gave flowers

Question 6) báus glaye kyori alha nái= which flowers did the man give to the woman

Notice that in 5, nái and the word that it is conjoined with, can not be seperated by the pilana ye.

"which one" would be translated as ʃì nái if we are referring to a non-A argument and non-human.

"which ones" would be translated as nò ʃì nái if we are referring to a non-A argument and non-human.

"which one" would be translated as ò nái if we are referring to a non-A argument but human.

"which ones" would be translated as ù nái if we are referring to a non-A argument but human.

Of course to refer to an A argument, we simple add -s to the pronoun.

..... How to ask a yes/no question

To turn a normal statement into a polar question (i.e. a question that requires a YES/NO answer), we stick the particle ʔái on the end of the sentence.

ʔái is neutral as to the response you are expecting. If you are expecting a positive reply, you would use the particle ʔaiwa instead.

To answer a positive question, YES or NO ( ʔaiwa àu aiya ) is sufficient.

To answer a negative question positively, YES ( ʔaiwa ) is enough.

To answer a negative question negatively, you must give an entire clause.

For example ;-

Statement 1) glà (rà) hauʔe = The woman is beautiful.

Question 1) glà hauʔe ʔái = Is the woman beautiful ? .......... If she is beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she isn't answer aiya.

Statement 2) glà (ká) hauʔe = The woman isn't beautiful.

Question 2) glà ká hauʔe ʔái = Isn't the woman beautiful ? ........ If she isn't beautiful, answer ʔaiwa, if she is answer ò rà hauʔe. (notice that the copula must be used in this case)

( in a later section we will see that it is not always necessary to use ʔái. When you have a clause with a modal, you simply change the word order to ask a polar question. ) ???

Also it is possible to focus on a particular element when asking a YES/NO question in béu. This is done by putting the particle cái after the element that you want to focus on. For example ...

Statement 1) báus glaye timpi alhai = the man gave flowers to the woman

Straight question 2) báus glaye timpi alha ʔái = did the man gave flowers to the woman ?

Focused question 3) báus glaye cái timpi alha = Is it the woman that the man gave flowers to ?

Actually there is a way to focused elements in a statement which mirrors the way to focus elements in a question. We use either cía or cìa for this.

Focused statement 4) báus glaye cía timpi alhai = It is the woman to whom the man gave the flowers.

The particle has a high tone if following a neutral tone word or a low tone word. If it focuses a high tone word it has a low tone i.e. cìa.

..... The other ʔainandaua

As well as the five question words given above, béu also has a question verb (ʔail-) meaning "to do what". For example ...

ʔailiri = "what will you do"

ʔailora jonos jene = "what is John doing to Jane"

It doesn't have to be fronted but it usually is.

..... The relativizers

The table below shows the béu relativizers.

| that, who, which | ʔài |

| where | bài |

| when | kài |

| as, in the manner that | dài |

| as | mài |

"that,who,which" gives the interlocutor the argument which is not stated in the clause following "that,who,which".

"where" gives the interlocutor the place which is not stated in the clause following "where".

"when" gives the interlocutor the time which is not stated in the clause following "when".

"how" gives the interlocutor the manner which is not stated in the clause following "how".

mài is slightly different ...

if placed after a noun, it gives the interlocutor the amount or number for that noun by means of the NP following mài.

twor ble? pàn mài (twor) gìn = I have as much money as you.

if placed after an adjective, it gives the interlocutor to the degree/level of that adjective by means of the NP following mài.

wáu òn (rà) nela mài wáu pàn = His eyes are as blue as my eyes.

I THINK THAT THIS IS OK. IS IT ??

One way in which the first three (ʔài, bài and kài) can be analysed, is to say that they are nominalizers, they turn a clause into a noun. Then you could say that a relative clause is simply a nominal that stands in apposition to the noun which it qualifies.

Now all these words found in the question toolbox are very common. Because of this, they have a shorthand way of being written. These are given below ...

..... The "whatever" constuction

ʔinʔa = "whatever"

There are 3 ʔinʔanandau ... ʔinʔa, ʔinʔai and ʔinʔau (meaning whatever, wherever and whenever)

ʔinʔaza = the "whatever" construction

béu has a similar construction to the English "whatever" construction.

?? Maybe we should consider it built up from a diachronic process.

1) solboi ʔá dori sawoi = Those drinks that she/he made are delicious

2) ʔín solboi ʔá dori sawoi = Any drink that she made is delicious

3) ʔín ʔá dori sawoi = Any that she made is delicious (solboi being understood from context)

4) ʔinʔa dori sawoi = Whatever she made is delicious (with the noun NOT being known from the context, unless it is that most generic of all nouns ... "thing"). See the section " ..... Question Words" for an interesting parallel to what is appearing here.

We can see that 4) could well have occurred diachronically from 3). ???

Now we have a new word ʔinʔa. If this is thought of as a word similar to the determiners or the quantifiers/specifiers which can either appear by themselves or with a noun, then it is not so strange to start getting constructions such as 5) occurring.

5) ʔinʔa solboi dori sawoi = Whatever drinks she made are delicious

ʔá dori is not allowed clause initially .... however dè ʔá dori or ʔinʔa dori sawoi is allowed.

however = ʔím we??

..... Pronouns

In this section we discuss pronouns and also introduce the S, A and O arguments.

béu is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings (in English there is a fixed word order, which also helps. In béu the word order is free).

timpa = to hit ... timpa is a verb that takes two nouns (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb).

pás ò timpari = I hit him pà ós timpori = He hit me ... OK in this case the protagonist marking in the verb also helps to make things disambiguous. But this will not always help, for example when both protagonists are third person and of the same number.

So far so good. And we see that English and béu behave in the same way so far. But what happens when we take a verb that takes only one noun (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb). For example doika = "to walk". In English we have "he walked". However in béu we don't have *ós doikori but ò doikori (equivalent to saying "*him walked" in English). So this in a nutshell is what an ergative language is.

It is the convention to call the doer in a intransitive clause the S argument. For example òS fomporta = She has tripped

It is the convention to call the "doer" in a transitive clause the A argument and the "done to" the O argument For example ósA timpori jeneO = He hit Jane

The S was historically from the word "Subject" and the O historically from the word "Object", but it is best just to forget about that. In fact when I use the word "subject" I am talking about either the S argument or the A argument.

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to"(O argument) : "he" is the "doer"(S argument) and the "doer to"(A argument).

In béu ò is the "done to"(O argument) and the "doer"(S argument) : ós is the "doer to"(A argument).

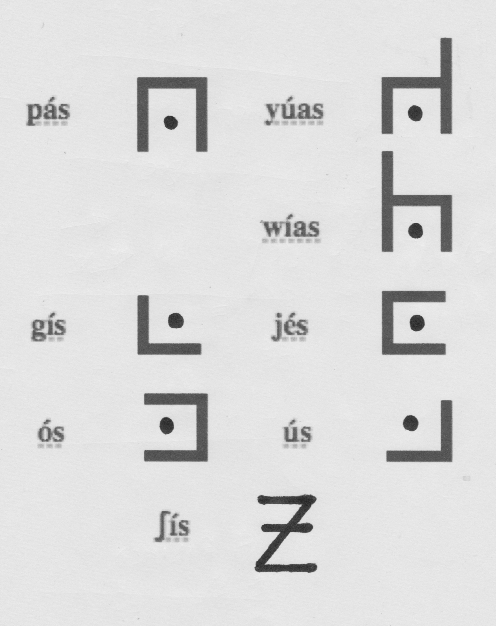

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the A argument.

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | ús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

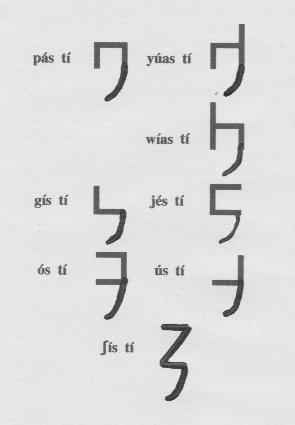

However these pronouns are never written out as above. There is a recognized "shorthand" method of writing them. This is shown below.

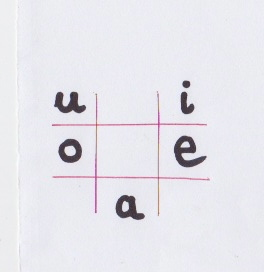

This method is based on the fact that all the pronouns have a different vowel sound (the ones that refer to humans anyway). A look at a béu vowel chart might let you work out what is happening here.

In fact these pronouns are usually dropped when possible, so it might be better to translate the above as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

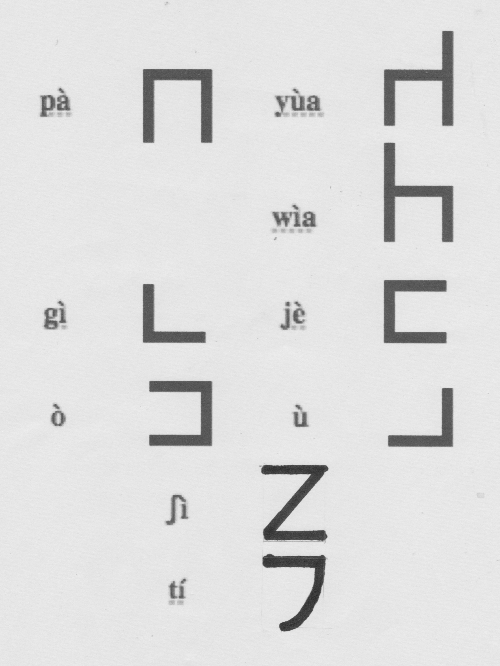

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the S or O argument. When they are used as S arguments it might be better to translate these pronouns as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | ù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

The above table is for S and O arguments, it fact we have another pronoun but this one only occurs as an O argument. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves we use tí to represent the O argument.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in béu we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari.

The table above shows the shorthand form for these non-ergative pronouns.

tí does not have to immediately* follow the ergative pronoun but it usually does. There is a recognised way to write the ergative pronoun plus the reflexive particle (i.e. we have one symbol to represent two words). These are shown below.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

Pronouns can just be set down beside each other if they both make up the same argument in a clause. Unlike normal nouns which must have é ( "and" ) between them and any other component.

*It is a rule that tí must follow the A argument.

The possessive form of these pronouns

| my | pàn | our | yùan |

| our | wìan | ||

| your | gìn | your (plural) | jèn |

| his, her | òn | their | ùn |

| its | ʃìn | their | ʃìn |

And we also have tín which is used if the possessor is the same as the subject of the clause.

Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences