Béu : Chapter 2: Difference between revisions

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

If definite they come before the verb, if not they come after. | If definite they come before the verb, if not they come after. | ||

('''é''' and '''è''' also code for indefiniteness ... maybe they are only necessary in oblique NP and subclauses ... maybe not necessary for S, A and O in main clauses) | |||

In subclauses there is a fixed order. It is VS and VAO. | In subclauses there is a fixed order. It is VS and VAO. | ||

Revision as of 08:49, 24 May 2014

..... Pronouns

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the A argument.

..

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ʃís | they | ʃís |

Because the person and number of the A or S argument is expressed in the actual verb. The above are usually dropped (however the third person pronoun is occasionally retained to give the distinction between human and non-human subject) so when the pronouns above are come across, it might be better to translate them as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

Below the form of the béu pronouns is the given for when the pronoun is the S or O argument. When they are used as an S arguments (i.e. with an intransitive verb), it might be better to translate these pronouns as "I myself", "you yourself" etc. etc.

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | ʃì | them | ʃì |

..

The above table is for S and O arguments, it fact we have another pronoun but this one only occurs as an O argument. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves we use tí to represent the O argument.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in béu we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari.

It is a rule that tí must follow the A argument (if it is overtly expressed ... i.e. by a free-standing pronoun and not just in the verb)

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in béu only one.

..

The possessive form of these pronouns are ...

..

| my | pàn | our | yùan |

| our | wìan | ||

| your | gìn | your (plural) | jèn |

| his, her | òn | their | nùn |

| its | ʃìn | their | ʃìn |

..

And we also have tín which is used if the possessor is the same as the subject of the clause.

Actually the n suffix is the locative. In the grammar, location and possession are marked identically.

This is similar to Scotch Gaelic. Consider Scotch Gaelic ... "Taigh agam" = "My house" (lit. "A house at me") *

Basically if n is appended to a noun that refers to a person, then the n indicates possession.

And if n is appended to a noun that refers to a place, then the n indicates location.

Sometimes the same affix can be used twice on the same word. For example cavia is a male first name.

Now in the béu lands it is quite common for small eateries and drinking establishments to be named after their owner, so cavian is, in the first instance an adjective meaning "belonging to cavia ". But in the second instance it can be a noun meaning "the place of cavia ". Then to indicate "at the place of cavia " you would have the word cavianon.**

*And in a similar way to Gaelic, béu has no possessive verb (i.e. it has no verb "to have")

Compare Gaelic ... "Tha taigh agam" — "I have a house" (lit. "A house is at me")

and béu ... twor nambo pàn — "I have a house" (lit. "Exists a house at me" or "There exists a house at me")

** Note the linking vowel o between the two n's. béu uses o as a linking vowel for nouns and e as a linking vowel for verbs.

..

..... The fundamentals of the grammar

..

This is an ergative language. The ergative marker is -s (-os for a word ending in a vowel).

In the main clause there is free word order. That is, you can have SV, VS, AVO, AOV, VAO, OVA, OAV, VOA.

The choices VAO/VOA and AOV/OAV are made on discourse grounds.

The other choices are made according to the definiteness of the S, A and O.

If definite they come before the verb, if not they come after.

(é and è also code for indefiniteness ... maybe they are only necessary in oblique NP and subclauses ... maybe not necessary for S, A and O in main clauses)

In subclauses there is a fixed order. It is VS and VAO.

Also in these subclauses the V is not really a verb but more a verbal noun, a maSdar, an infinitive if you will.

..

..... The noun phrase core

..

Now we talk about the béu noun phrase (fandauza).

The fandauza consists of the head hua (3) followed by one or more adjectives saidau (2) followed by a determiner (1). Only the head is mandatory.

1) The set of possible determiners is very small in béu. Only three ... dí "this", or dè "that" or nái "which".

In the Western Linguistic tradition "which" is not usually thought of as a determiner. It is however in the béu linguistic tradition. When nái is used you of course have a question.

2) Not much to say about this one, you can string together as many as you like ... the same as in English. Also genitives are put in this slot. A genitive is a word derived from a noun by the suffixing of -n (or -on) which indicates possession*. Genitives always come after the regular adjective.

*Actually it can also stand for a location ... where the NP is at.

3) This is usually a noun. However it can also be an adjective. When it is an adjective it has concrete reference instead of representing a quality (as happens often in English). For instance, when talking about ... say ... a photograph, you could say "the green is too dark". In this sentence "the green" is a NP meaning the quality of being green. In béu if green is used as the head of a NP it always means "the green one" : "the person/thing that is green".

In béu, geunai would be used in a sentence such as "the green is too dark".

gèu = "green" or "the green one"

geunai = "greenness"

saco = "slow" or "the slow one"

saconi = "slowness"

Notice that the suffix has two forms ... depending upon whether the base adjective has one syllable or more than one syllable.

Sometimes the head is a determiner. In these cases the NP is understood to refer to some noun ... but it is not spoken ... it is just understood by all parties. In these cases the determiners undergo a change of form ...

dí => adi = "this one"

dè => ade = "that one"

nái => anai = "which one"

Related to dí and dè are the two nouns dían (here) and dèn (there). Although nouns, they never occur with the locative case or the ergative case.

..

..... The extended noun phrase

Actually around the NP core you can have some other elements.

The specifiers

The specifiers = nandau.a koiʒi or just koiʒia

koiʒi actually means "preface" as in "the preface to the book"

Immediately before the core you can have a specifier.

There consist of the following ...

"no" (kyà), "any" (í), "some"(singular) (é), "every" (yú), "some"(plural) (è), "plurality" (nò), "all" (ù), "two" (auva) => 1727 (ataitauta), many" (uwe), "a few" (iyo)

Notice that the specifier that implies zero number has low tone, the 3 specifiers that imply singular* number have high tone and the 3 specifiers that imply plural* number have low tone.

.* Well this is true for the English translations anyway. Actually I am not so sure about the "logic" of my little scheme. Also I would like to compare how a spectrum of other languages use specifiers.

Also note that nò is a noun (meaning "number") as well as a particle that denotes plurality. In the béu mathematical tradition, nò means a number from 2 -> 1727 only (of course there are expressions for expanding the concept to integers, rational numbers etc. etc.)

After a koiʒi the head is always in its base form with regard to number. For example

é glà = some woman

è glà = some women ... not *è gala

í toti = any child .......... not *í totai

The are 2 cases where you can have two koiʒi together ... é nò or when you have í followed by a number greater than one. For example ...

é nò toti = some child or children

í auva toti = any two children

..

The forms of adi, ade and anai when plurality must be expressed, are nò dí, nò dè and nò nái

..

The forms of adi and ade when emphasis must be expressed, are á dí and á dè. ..

When plurality AND emphasis must be expressed, we have á nò dí, á nò dè and á nò nái

| 1 | ú báu dí | all of these men | OR | all these men |

| 2 | uwe báu dí | many of these men | ||

| 3 | iyo báu dí | few of these men | OR | a few of these men |

| 4 | auva báu dí | two of these men | ETC | ETC |

| 5 | kyà báu dí | none of these men | ||

| 6 | í báu dí | any of these men | OR | any one of these men |

| 7 | é báu dí | one of these men | ||

| 8 | è báu dí | some of these men | ||

| 9 | yú báu dí | every one of these men | ||

| 10 | nò báu dí | several of these men | OR | several of these men here |

| 11 | é nò báu dí | one or more of these men | ||

| 12 | í auva báu dí | any two of these men | ETC | ETC |

The above table is worth discussing ... for what it tells us about English as much as anything else.

..

One line 1 ... I do not know why "all these men" is acceptable ... on every other line "of" is needed (to think about)

Similarly on line 3 ... I do not know why "a few" is a valid alternative.

Notice that *<-sup>aja báu dí does not exist. It is illegal. "one of these men" is expressed on line 7. aja only used in counting ???

I should think more on the semantic difference between line 10 and line 8. ???

line 1 and line 9 are interesting. Every language has a word corresponding to "every" (or "each", same same) and a word corresponding to "all". Especially when the NP is S or A, "all" emphasises the unity of the action, while "every" emphasises the separateness of the actions. Now of course (maybe in most cases) this dichotomy is not needed. It seems to me, that in that case, English uses "every" as the default case (the Scandinavian languages use "all" as the default ??? ). In béu the default is "all" ú.

On line 9, it seems that "one" adds emphasis to the "every". Probably, not so long ago, "every" was valid by itself. The meaning of this word (in English anyway) seems particularly prone to picking up other elements (for the sake of emphasis) with a corresponding lost of power for the basic word when it occurs alone. (From Etymonline EVERY = early 13c., contraction of Old English æfre ælc "each of a group," literally "ever each" (Chaucer's everich), from each with ever added for emphasis. The word still is felt to want emphasis; as in Modern English every last ..., every single ..., etc.)

..

In the last section we introduced the rule, that when a determiner is the head, then the determiner changes form (an a is prefixed to it)

Now we must introduce an exception to that rule ... when you have a specifier just to the left of a determiner (in this conjunction, the determiner MUST be the head) the determiner takes its original form.

Emphasis is always used when contrasting two things. as in "this is wet, but that is dry" etc etc.

The emphatic particle

Now even before the specifiers it is possible to have an element. This is the emphatic particle á.

This is also used as a sort of vocative case. Not really obligatory but used before a persons name when you are trying o get their attention.

When this particle comes directly in front of adi, ade and anai an amalgamation takes place ( á adi etc etc are in fact illegal)

á adi => ádí = "this one!"

á ade => ádé = "that one!"

á anai => ánái = "which one!"

These three words break the rule that only monosyllabic words can have tone. These 3 words are the only exception to that rule.

By the way, when written using the béu writing system, only the initial a has the dot which indicates high tone. The second syllable is unmarked for tone.

The relative clause

The relativizer is à.

The relativizer in béu is à. This takes all the pilana the same as a normal noun.

the basket api the cat shat was cleaned by John.

the wall ala you are sitting was built by my grandfather.

the woman aye I told the secret, took it to her grave.

the town avi she has come is the biggest south of the mountain.

the lilly pad à alya the frog jumped was the biggest in the pond.*<-sup>

the boat à alfe you have just jumped is unsound.*<-sup>

báu ás timpori glá rà ʔaiho = The man that hit the woman is ugly.

nambo àn she lives is the biggest in town.

Note ... The man whose dog I shot, reported me to the police = the man that own dog that I shot, reported me to the police

báu aho ò is going to market is her husband.

the knife age he severed the branch is a 100 years old

The old woman aji I deliver the newspaper, has died.

The boy aco they are all talking, has gone to New Zealand.

..

..... 72 Adjectives

..... 4 of which serve as intransitive verbs

..

| bòi * | good | boizora | she is healthy | bòis | to be healthy/health |

| kéu | bad | keuzora | he is ill | kéus | to be sick/illness |

| fái | rich ** | faizora | she is interested | fáis | to be attentive/attention |

| pàu | bland | pauzora | he is bored | pàus | to be bored/boredom |

* Note that the adverb version of this word is slightly irregular. Instead of boiwe it is bowe. People often shout this when impressed with some athletic feat or sentiment voiced ... bowe bowe => well done => bravo bravo

Also instead of keuwe we have kewe. People often shout kewe kewe kewe if they are unimpressed with some athletic feat or disagree with a sentiment expressed. Equivalent to "Booo boo".

**In a non-monetary sense. If applied to food it means many flavours and/or textures. If applied to music it means there is polyphony. If applied to physical design it means baroque.

..

... 14 of which don't serve as any type of verbs

..

| igwa | equal, the same |

| uʒya | different, not the same |

| sài | young |

| gáu | old (of a living thing) |

| jini | clever, smart |

| tumu | stupid, thick |

| nìa | near |

| múa | far |

| wenfo | new |

| yompe | old, former, previous |

| cùa | east, dawn, sunrise |

| día | west, dusk, sundown |

| lugu | right, positive |

| liʒi | left, negative |

..

(Of course you can always use a periphrastic expression if you wanted.)

... 54 of which serve as transitive verbs

..

| boʒi | better | kegu | worse | bozori | he improved something | kegori | he made something worse | boʒis | to improve | kegus | to made something worse |

| faizai | richer | paugau | blander | faizori | she developed something | paugau | she run something down | faizais | to enrich/develope | paugaus | to run down |

| ái | white | àu | black | aizori | he whitened something | auzori | he turned something black | áis | to whiten | àus | to blacken |

| hái | high | ʔàu | low | haizori | she raised something | ʔauzori | she lowered something | háis | to raise | ʔàus | to lower |

| guboi | deep | sikeu | shallow | gubori | she deepened something | sikori | she made something shallow | gubois | to deepen | sikeus | to make shallow |

| seltia | bright | goljua | dim | seltori | he brightened something | goljua | he dimmed something | seltias | to brighten | goljuas | to dim |

| taiti | tight | jauju | loose | taitori | she tightened something | jaujori | she loosened something | taitis | to tighten | jaujus | to loosen |

| jutu | big | tiji | small | jutori | he expanded something | tijori | he shrank something | jutus | to enlarge | tijis | to shrink |

| felgi | hot | polzu | cold | felgori | she heated something up | polzori | she cooled something down | felgis | to heat | polzus | to cool down |

| maze | open | nago | closed | mazori | he opened something | nagori | he closed something | mazes | to open | nagos | to shut |

| baga | simple | kaza | complex | bagori | she simplified something | kazori | she complicated something | bagas | simplify | kazas | to complicate |

| naike | sharp | maubo | blunt | naikori | he sharpened something | maubori | he blunts something | naikes | to sharpen | maubos | to blunt |

| nucoi | wet | mideu | dry | nucori | she made something wet | midori | she dried something | nucois | to make wet | mideus | to dry |

| fazeu | empty | pagoi | full | fazori | he emptied something | pagori | he filled something | fazeus | to empty | pagois | to fill |

| saco | fast | gade | slow | sacori | she speeded something up | gadori | she slowed something down | sacos | to accelerate | gades | to decelerate |

| wobua | heavy | yekia | light | wobori | he loaded something up | yekori | he unloaded something | wobuas | to load up | yekias | to unload |

| haube | beautiful | ʔaiko | ugly | haubori | she beautified something | ʔaikori | she made something ugly | haubes | beautify | ʔaikos | to make ugly |

| pujia | thin | fitua | thick | pujori | he made something thin | fitori | he made something thick | pujias | to make thin | fituas | to thicken |

| yubau | strong | wikai | weak | yubori | she strengthened something | wikori | she weakened something | yubaus | to strengthen | wikais | to weaken |

| ailia | neat | aulua | untidy | ailori | he tidied up something | aulori | he messed something up | ailias | to tidy up | auluas | to mess up |

| fuje | soft | pito | hard | fujori | she softened something | pitori | she hardened something | fujes | to soften | pitos | to harden |

| joga | wide | teza | narrow | jogori | he widened something | tezori | he narrowed something | jogas | to broaden | tezas | to narrow |

| gelbu | rough | solki | smooth | gelbori | she made something rough | solkori | she smoothed something | gelbus | to roughen | solkis | to smooth |

| ʔoica | clear | heuda | hazy | ʔoicori | she explained something | heudori | she confused somebody (intentionally) | ʔoicas | to explain | heudas | to muddy the waters |

| selce | sparce | goldo | dense | selcori | he pruned something | goldori | he intensified something | selces | to prune | goldos | to intensify |

| cadai | fragrant | dacau | stinking | cadori | she made fragrant | dacori | she made stinky | cadais | to make fragrant | dacaus | to to make stinky |

| detia | elegant | cojua | crude | detori | he decorated something | cojori | he decorated something BADLY | detias | to decorate | cojuas | to decorate in a gauche style |

..

The top 4 adjectives in the table above are actually irregular comparatives.

The standard method for forming the comparative and superlative is ... ái = white : aige = whiter : aimo = whitest

..

However not quite all antonyms fall into the above pattern. For example ...

| loŋga | long | tìa | short | loŋgori | he lengthened something | tiazori | he shortened something | loŋgas | to lengthen | tìas | to shorten |

..

..... Antonym phonetic correspondence

..

In the above lists, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning from each other. However in béu there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | ai | |||

| f | e | |||

| b | eu | |||

| g | u | |||

| d | ua | high tone | ||

| u | =========================== | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ia | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | i | |||

| k | oi | |||

| p | o | |||

| t | au | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

Note ... The original idea of having a regular correspondence between the two poles of a antonym pair came from an earlier idea for the script. In this early script, the first 8 consonants had the same shape as the last 8 consonants but turned 180˚. And in actual fact the two poles of a antonym pair mapped into each other under a 180˚ turn.

An adjectives is called moizana in béu

moizu = attribute, characteristic, feature

And following the way béu works, if there is an action that can be associated with noun (in any way at all), that noun can be co-opted to work as an verb.

Hence moizori = he/she described, he/she characterized, he/she specified ... moizus = the noun corresponding to the verb on the left

moizo = a specification, a characteristic asked for ... moizoi = specifications ... moizana = things that describe, things that specify

nandau moizana = an adjective, but of course, especially in books about grammar, this is truncated to simply moizana

..

..... The pilana

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON are called "cases". The classical languages, Greek and Latin had 5 or 6 of these. Modern-day Finnish has about 15 (it depends on how you count them, 1 or 2 are slowly fading away). Present day English still has a relic of a once more extensive case system : most pronouns have two forms. For example ;- the third-person:singular:male pronoun is "he" if it represents "the doer", but "him" if it represents "the done to".

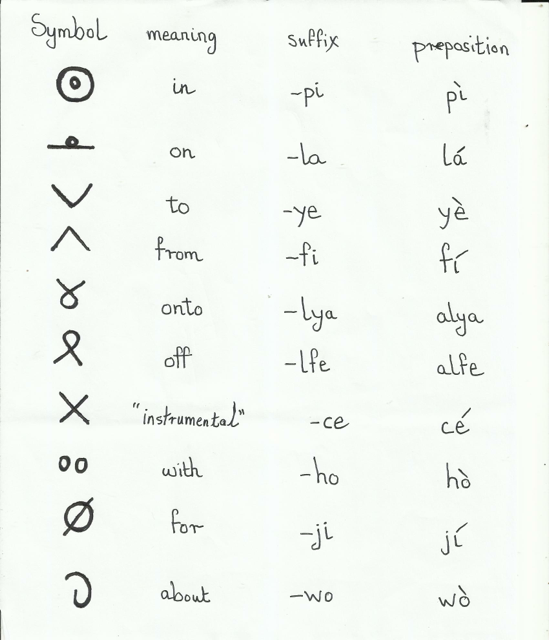

The 12 béu case markers are called pilana

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana <= (pila + ana), in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle". It is an adjective which means "putting (something) in position".

As béu adjectives freely convert to nouns*, it also means "that which puts (something) in position" or "the positioner".

Actually only a few of them live up to this name ... nevertheless the whole set of 12 are called pilana in the béu linguistic tradition.

..

..

The pilana are suffixed to nouns and specify the roll these nouns play within a clause.

As well as the 10 illustrated above, we have s for the ergative case and n for the locative case. Also we have the unmarked case which represents the S or O argument.

sá and nà are the free-standing variants of -s and -n.

The pilana specify the roll that a noun has within a clause. However both the ergative case and the locative case (and a few other cases) can specify what rolls a noun has within a NP.

For example nambo pàn = "a/the house at me" or "my house"

timpa báus glà = the man's hitting of the woman ... this is an example of an infinitive NP.

letter blicovi = the letter from the king

pen gila = a pen on your person

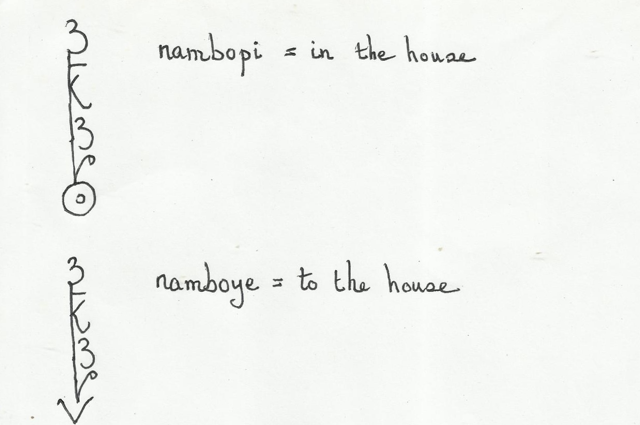

As shown above the pilana are represented by their own symbols. Or at least the ten that do not consist of single letters.

For the suffix form of the first 2 and last 2 symbols given above, the end of the word proper "touches" the symbol. For the other 6 symbols, the word proper "impinges" upon the symbol. See below ...

..

..... Rules governing the pilana

..

Now one quirk of béu (something that I haven't heard of happening in any natural language), is that the pilana is sometimes realised as an affix to the head of the NP, but sometimes as a preposition in front of the entire NP. This behaviour can be accounted for with thing with two rules.

1) The pilana attaches to the head and only to the head of the NP.

2) The NP is not allowed to be broken up by a pilana. The whole thing must be contiguous. So if a NP has elements after the head the case must be realised as a preposition and be placed in front of the entire noun phrase.

3) No two pilana can be stuck together (WOULD THIS EVER HAPPEN ??)

So if we have a NP with elements to the right of the head, then the pilana must become a preposition. The prepositional forms of the pilana are given on the above chart to the right. These free-standing particles are also written just using the symbols given on the above chart to the left. That is in writing they are shorn of their vowels as their affixed counter-parts are.

Here are some examples of the above rules ...

..

fanfa = horse

sonda = son

blico = king

fanfa sondan = the horse of the son

sonda blico = the son of the king

However the suffixed form can only be used if the genitive is a single word. Otherwise the particle na must be placed in front of the words that qualify. For example ;-

We can't say *fanfa sondan blicon however. The -n on sonda is splitting the NP sonda blico.

So we must say fanfa nà sonda blicon

Some more examples ...

fanfa nà sonda jini blicon = "the horse of the king's clever son

fanfa nà sonda nà blico somua = "the horse of the fat king's son"

..

Here are some more examples of the above rules ...

pintu nambo = the door of the house

pintu nà nambo tuju = the door of the big house

When one of the specifiers is involved we have two permissible arrangements.

1) pintu á nambon= the door of some house

2) pintu nà á nambo = the door of some house

1) is the more usual way to express "the door of some house", but 2) is also allowed as it doesn't break any of the rules.

This also goes for numbers as well as specifiers.

papa auva sondan = the father of two sons

papa nà auva sonda = the father of two sons

..

*Another case when the pilana must be expressed as a prepositions is when the noun ends in a constant. This happens very, very rarely but it is possible. For example toilwan is an adjective meaning "bookish". And in béu as adjectives can also act as nouns in certain positions, toilwan would also be a noun meaning "the bookworm". Another example is ʔokos which means "vowel".

... Index

- Introduction to Béu

- Béu : Chapter 1 : The Sounds

- Béu : Chapter 2 : The Noun

- Béu : Chapter 3 : The Verb

- Béu : Chapter 4 : Adjective

- Béu : Chapter 5 : Questions

- Béu : Chapter 6 : Derivations

- Béu : Chapter 7 : Way of Life 1

- Béu : Chapter 8 : Way of life 2

- Béu : Chapter 9 : Word Building

- Béu : Chapter 10 : Gerund Phrase

- Béu : Discarded Stuff

- A statistical explanation for the counter-factual/past-tense conflation in conditional sentences